Sumatriptan

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Imitrex, Imigran,Treximet |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | tablet, subcutaneous injection, nasal spray, transdermal electrophoresis |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 15% (oral)/ 96% (s.c) |

| Protein binding | 14–21% |

| Metabolism | MAO |

| Elimination half-life | 2.5 hours |

| Excretion | 60% urine; 40% feces |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.130.518 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H21N3O2S |

| Molar mass | 295.402 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Sumatriptan is a medication used for the treatment of migraine headaches.[1]

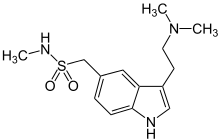

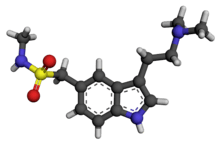

It is a synthetic drug belonging to the triptan class. Structurally, it is an analog of psilocybin, and features an N-methyl sulfonamidomethyl group at position C-5 on the indole ring.[2]

Sumatriptan is produced and marketed by various drug manufacturers with many different trade names such as Imitrex, Imigran, Sumatran, Sumatriptanum, and Sumax, also as Treximet as an oral combination product with naproxen sodium.

Medical uses

Sumatriptan is effective for ending or relieving the intensity of migraine and cluster headaches.[1] It is most effective when taken early after the start of the pain.[1] Injected sumatriptan is more effective than other formulations.[3]

Adverse effects

Overdose of sumatriptan can cause sulfhemoglobinemia, a rare condition in which the blood changes from red to green, due to the integration of sulfur into the hemoglobin molecule.[4] If sumatriptan is discontinued, the condition reverses within a few weeks.

Serious cardiac events, including some that have been fatal, have occurred following the use of sumatriptan injection or tablets. Events reported have included coronary artery vasospasm, transient myocardial ischemia, myocardial infarction, ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation (V-Fib).[5]

The most common side effects[6] reported by at least 2% of patients in controlled trials of sumatriptan (25-, 50-, and 100-mg tablets) for migraine are atypical sensations (paresthesias and warm/cold sensations) reported by 4% in the placebo group and 5–6% in the sumatriptan groups, pain and other pressure sensations (including chest pain) reported by 4% in the placebo group and 6–8% in the sumatriptan groups, neurological events (vertigo) reported by less than 1% in the placebo group and less than 1% to 2% in the sumatriptan groups. Malaise/fatigue occurred in less than 1% of the placebo group and 2–3% of the sumatriptan groups. Sleep disturbance occurred in less than 1% in the placebo group to 2% in the sumatriptan group.

Mechanism of action

Sumatriptan is structurally similar to serotonin (5-HT), and is a 5-HT receptor (types 5-HT1D and 5-HT1B[7]) agonist. Sumatriptan's primary therapeutic effect, however, is in its inhibition of the release of Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), likely through its 5-HT1D/1B receptor-agonist action.[8] This is substantiated by the efficacy of newly developed CGRP antagonists and antibodies in the preventative treatment of migraine.[9] However, how agonism of the 5-HT1D/1B receptors inhibits CGRP release is not fully understood. CGRP is believed to cause sensitization of trigeminal nociceptive neurons, contributing to the pain experienced in migraine.[10]

Sumatriptan is also shown to decrease the activity of the trigeminal nerve, which presumably accounts for sumatriptan's efficacy in treating cluster headaches. The injectable form of the drug has been shown to abort a cluster headache within 30 minutes in 77% of cases.[11]

Pharmacokinetics

Sumatriptan is administered in several forms: tablets, subcutaneous injection, and nasal spray. Oral administration (as the succinate salt) suffers from poor bioavailability, partly due to presystemic metabolism—some of it gets broken down in the stomach and bloodstream before it reaches the target arteries. A new rapid-release tablet formulation has the same bioavailability, but the maximum concentration is achieved on average 10–15 minutes earlier. When injected, sumatriptan is faster-acting (usually within 10 minutes), but the effect lasts for a shorter time. Sumatriptan is metabolised primarily by monoamine oxidase A into 2‐{5‐[(methylsulfamoyl)methyl]‐indole‐3‐yl}acetic acid which is then conjugated to glucuronic acid. These metabolites are excreted in the urine and bile. Only about 3% of the active drug may be recovered unchanged.

There is no simple, direct relationship between sumatriptan concentration (pharmacokinetics) per se in the blood and its anti-migraine effect (pharmacodynamics). This paradox has, to some extent, been resolved by comparing the rates of absorption of the various sumatriptan formulations, rather than the absolute amounts of drug that they deliver.[12][13]

Approval

Sumatriptan was the first clinically available triptan (in 1991). In the United States, it is available only by medical prescription (and is frequently limited, without prior authorization, to a quantity of nine in a 30-day period). This requirement for a medical prescription also exists in Australia.[14] However, it can be bought over the counter in the UK[15] and Sweden.[16] Several dosage forms for sumatriptan have been approved, including tablets, solution for injection, and nasal inhalers.

On April 15, 2008, the US FDA approved Treximet, a combination of sumatriptan and naproxen, an NSAID.[17] This combination has shown a benefit over either medicine used separately.[18]

In July 2009, the US FDA approved a single-use jet injector formulation of sumatriptan. The device delivers a subcutaneous injection of 6 mg sumatriptan, without the use of a needle. Autoinjectors with needles have been previously available in Europe and North America for several years.[19]

Phase III studies with a iontophoretic transdermal patch (Zelrix/Zecuity) started in July 2008.[20] This patch uses low voltage controlled by a pre-programmed microchip to deliver a single dose of sumatriptan through the skin within 30 minutes.[21][22] Zecuity was approved by the US FDA in January 2013.[23] Sales of Zecuity have been stopped following reports of skin burns and irritation.[24]

Generics

On November 6, 2008, Par Pharmaceutical announced that it would begin shipping generic versions of sumatriptan injection (sumatriptan succinate injection) 4- and 6-mg starter kits and 4- and 6-mg filled syringe cartridges to the trade immediately. In addition, Par anticipates launching the 6-mg vials early in 2009.[25]

Mylan Laboratories Inc., Ranbaxy Laboratories, Sandoz (a subsidiary of Novartis), Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, and other companies have received FDA approval for generic versions of sumatriptan tablets in 25-, 50-, and 100-mg doses since 2009. The drug is generically available in U.S. and European markets, since Glaxo's patent protections have expired in those jurisdictions. Nasal spray sumatriptan is also generically available.[26]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Derry, CJ; Derry, S; Moore, RA (28 May 2014). "Sumatriptan (all routes of administration) for acute migraine attacks in adults - overview of Cochrane reviews". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD009108. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009108.pub2. PMID 24865446.

- ↑ The presence of the sulfonamide group in the molecule does not make sumatriptan a "sulfa drug".

- ↑ Dahlöf, Carl G. H. "Sumatriptan: Pharmacological Basis and Clinical Results". Medscape. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ "Patient bleeds dark green blood". BBC News. 8 June 2007. Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- ↑ Kelly KM (June 1995). "Cardiac arrest following use of sumatriptan". Medline. 45 (6): 1211–3. doi:10.1212/wnl.45.6.1211. PMID 7783891.

- ↑ "Tablets". fda.gov. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ↑ Razzaque Z, Heald MA, Pickard JD, et al. (1999). "Vasoconstriction in human isolated middle meningeal arteries: determining the contribution of 5-HT1B- and 5-HT1F-receptor activation". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 47 (1): 75–82. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00851.x. PMC 2014192. PMID 10073743.

- ↑ Juhasz, G; Zsombok, T; Jakab, B; Nemeth, J; Szolcsanyi, J; Bagdy, G (2016-06-26). "Sumatriptan Causes Parallel Decrease in Plasma Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) Concentration and Migraine Headache During Nitroglycerin Induced Migraine Attack". Cephalalgia. 25 (3): 179–183. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00836.x. PMID 15689192.

- ↑ Tso, Amy R.; Goadsby, Peter J. (2017-08-01). "Anti-CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies: the Next Era of Migraine Prevention?". Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 19 (8): 27. doi:10.1007/s11940-017-0463-4. ISSN 1092-8480. PMC 5486583. PMID 28653227.

- ↑ Giniatullin, Rashid; Nistri, Andrea; Fabbretti, Elsa (2008-02-01). "Molecular Mechanisms of Sensitization of Pain-transducing P2X3 Receptors by the Migraine Mediators CGRP and NGF". Molecular Neurobiology. 37 (1): 83–90. doi:10.1007/s12035-008-8020-5. ISSN 0893-7648. PMID 18459072.

- ↑ "Treatment of acute cluster headache with sumatriptan. The Sumatriptan Cluster Headache Study Group". N Engl J Med. 325 (5): 322–6. 1991. doi:10.1056/NEJM199108013250505. PMID 1647496.

- ↑ Fox, A. W. (2004). "Onset of effect of 5-HT1B/1D agonists: a model with pharmacokinetic validation". Headache. 44 (2): 142–147. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04030.x. PMID 14756852.

- ↑ Freidank-Mueschenborn, E.; Fox, A. (2005). "Resolution of concentration-response differences in onset of effect between subcutaneous and oral sumatriptan". Headache. 45 (6): 632–637. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05129a.x. PMID 15953294.

- ↑ "Poisons Standard June 2017". 18 May 2017. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ↑ "Press release: First Over The Counter (OTC) migraine pill made available". Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Archived from the original on 2014-12-05. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ↑ European Medicines Agency (23 November 2011). "Assessment Report: Sumatriptan Galpharm 50 mg Tablets" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ "GSK press release – Treximet (sumatriptan and naproxen sodium) tablets approved by FDA for acute treatment of migraine". gsk.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ↑ Brandes JL, Kudrow D, Stark SR, et al. (April 2007). "Sumatriptan-naproxen for acute treatment of migraine: a randomized trial". JAMA. 297 (13): 1443–54. doi:10.1001/jama.297.13.1443. PMID 17405970.

- ↑ Brandes, J.; Cady, R.; Freitag, F.; Smith, T.; Chandler, P.; Fox, A.; Linn, L.; Farr, S. (2009). "Needle-free subcutaneous sumatriptan (Sumavel DosePro): bioequivalence and ease of use". Headache. 49 (10): 1435–1444. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01530.x. PMID 19849720.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT00724815 for "The Efficacy and Tolerability of NP101 Patch in the Treatment of Acute Migraine (NP101-007)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ "SmartRelief -electronically assisted drug delivery (iontophoresis)". nupathe.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ↑ Pierce, M; Marbury, T; O'Neill, C; Siegel, S; Du, W; Sebree, T (2009). "Zelrix: a novel transdermal formulation of sumatriptan". Headache. 49 (6): 817–25. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01437.x. PMID 19438727.

- ↑ "Zecuity Approved by the FDA for the Acute Treatment of Migraine". nupathe.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ↑ "Teva pulls migraine patch Zecuity on reports of burning, scarring | FiercePharma". www.fiercepharma.com. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ↑ "Par Pharmaceutical begins shipment of sumatriptan injection". Par Pharmaceutical. 6 November 2008. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ↑ LaMattina, John (2 March 2015). "If You 'Want To Make A Good Drug Great' Cost Must Be Factored In". Forbes. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.