Hurricane Lane (2018)

| Category 5 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Lane near peak intensity southeast of Hawaii on August 21 | |

| Formed | August 15, 2018 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 29, 2018 |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 160 mph (260 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 922 mbar (hPa); 27.23 inHg |

| Fatalities | 1 total |

| Damage | > $200 million (2018 USD) |

| Areas affected | Hawaii |

| Part of the 2018 Pacific hurricane season | |

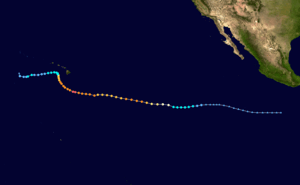

Hurricane Lane was the wettest tropical cyclone on record in Hawaii, with rainfall accumulations of 52.02 inches (1,321 mm) in Mountain View, also ranking as the second-wettest tropical cyclone in the United States, after Hurricane Harvey of 2017. The first Category 5 Pacific hurricane since Patricia in 2015, Lane was the twelfth named storm, sixth hurricane, and fourth major hurricane of the 2018 Pacific hurricane season. It originated from a tropical wave that began producing disorganized thunderstorm activity several hundred miles off the southern coast of Mexico on August 11. Over the next four days, the disturbance gradually strengthened amid favorable atmospheric and thermodynamic conditions and became a tropical depression early on August 15. Twelve hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Lane. Gradual strengthening occurred for the next day and a half, which resulted in Lane reaching hurricane status by August 17, followed by rapid intensification that brought Lane to its initial peak intensity as a Category 4 hurricane on August 18. On August 19, Lane crossed into the Central Pacific basin, where increased wind shear weakened it. However, on August 20, Lane re-intensified into a Category 4 hurricane, and reached Category 5 intensity early on August 22. As Lane approached the Hawaiian Islands, it began to weaken as vertical wind shear once again increased, dropping below hurricane status on August 25. Over the next few days, Lane began a westwards course away from the Hawaiian Islands as influence from the easterly trade winds increased as Lane weakened. On August 29, Lane became a remnant low, and dissipated shortly afterward.

Hurricane Lane was only the second Category 5 hurricane to pass within 350 miles (560 km) of South Point, Hawaii. The other one was John in 1994.[1] Lane prompted the issuance of hurricane watches and warnings for every island in Hawaii. From August 22 to 26, Lane brought heavy rain to much of the Hawaiian Windward Islands, which caused flash flooding and mudslides. Strong winds downed trees and power lines on Maui, and brush fires ignited on both Maui and Oahu. One fatality occurred on Kauai, and damage across the state reached at least $200 million (2018 USD).

Meteorological history

Early on August 11, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) began monitoring a tropical wave that was producing disorganized thunderstorm activity several hundred miles off the southern coast of Mexico.[2] The disturbance moved generally westward for the next four days, before becoming much better organized late on August 14.[3] At 03:00 UTC on August 15, the NHC declared that Tropical Depression Fourteen-E had formed 1,115 miles (1,795 km) southwest of the southern tip of Baja California Peninsula.[4] Twelve hours later, the depression intensified to a tropical storm, receiving the name Lane, based on the development of banding features and a Dvorak intensity estimation. The NHC also forecast Lane to strengthen into a hurricane.[5]

Lane gradually strengthened for the next day or so, before becoming a hurricane early on August 17.[6] For the next several days, Lane was steered in a west to west-northwest direction by a subtropical ridge to the north.[7] Shortly after becoming a hurricane, Lane then began a period of rapid intensification, quickly becoming a strong Category 2 hurricane eighteen hours later.[8] Lane's wind field nearly doubled during this period, and the eye began to become less cloudy after a strong convective ring formed around the core of the hurricane.[9] Lane continued its rapid intensification, becoming the fourth major hurricane of this season six hours later.[10] On August 18, Lane strengthened further to a Category 4 hurricane.[11] The satellite presentation had also improved immensely overnight. At that time, the hurricane had a well-defined eye surrounded by very deep convection and symmetric outflow, which contributed to additional strengthening.[12] Six hours later, Lane reached its initial peak with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (220 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 948 mbar (27.99 inHg).[13] The NHC issued its final advisory on Lane late on August 18, as it approached 140°W, the boundary between the eastern and central Pacific basins.[14]

Early on August 19, Lane crossed over into the Central Pacific Basin, where the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC) took over responsibility for issuing advisories on and monitoring the cyclone.[15] At that time, Lane began a weakening trend, as it encountered increasing wind shear from the west-southwest, falling to Category 3 status six hours later.[16] Despite repeated forecasts calling for the storm to continue weakening,[17] Lane maintained its intensity throughout on August 20. Later that day, it reattained Category 4 status.[18] Afterward, Lane continued to strengthen. On August 21, Lane began its turn to the northwest, as it moved between a weakening mid-level ridge to the east and a developing upper-level trough to the northwest.[19] Early on August 22, aircraft reconnaissance data indicated that Lane had intensified into a Category 5 hurricane, with 1-minute sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h).[20][21] Several hours later, Lane weakened back to a high-end Category 4 hurricane.[22] On August 23, the northwest eyewall of Lane passed over a NOAA buoy located about 250 miles (400 km) southwest of the Big Island, which recorded peak winds of 107 mph (172 km/h).[23] Early on August 24, southwesterly wind shear weakened Lane to a Category 3 hurricane.[24] At the same time, the hurricane began travelling in a north-northwest motion because of a developing deep layer ridge to the east and southeast.[25] Lane then took a turn to the north and later to the north-northeast, as the ridge continued to develop.[26] Later that day, Lane dropped below the threshold of major hurricane as wind shear continued to impact the system.[27]

The weakening trend accelerated as wind shear increased. Lane weakened to a Category 1 hurricane early on August 25,[28] and dropped below hurricane strength just three hours later,[29] based on the rapid degradation of the cloud pattern. The storm's center of circulation became exposed and the deep convection was sheared to the northeast.[30] Fifteen hours later, Lane made its closest approach to Hawaii, approximately 110 miles (175 km) south-southeast of Honolulu.[31] Starting from August 25, Lane's direction of travel fluctuated, and the storm's forward motion stalled.[32] Late on that day, Lane took a sharp turn to the west,[33] under the influence of the low-level easterlies.[27] On August 26, Lane weakened further into a tropical depression in a hostile environment, while continuing to head westward.[34] However, on the next day, Lane reintensified into a tropical storm once again, as convection burst in the eastern semicircle, and the convective banding in the southeast of the storm also increased.[35] Nonetheless, this strengthening trend was short-lived, and Lane weakened into a tropical depression once again early on August 28.[36] Later that day, Lane turned to the northwest under the influence of a developing low-level trough.[37] Early on August 29, Lane degenerated into a remnant low, while turning northward, as the center of the storm became elongated.[38] Later on the same day, the remnant cyclone was absorbed by a developing upper-level low, which later became a subtropical storm on August 31, near the International Date Line.[39]

Preparations

.jpg)

On August 21, as Lane approached the Hawaiian Islands, a hurricane watch was issued for Maui County and Hawaii County.[40] On the next day, the hurricane watch for Hawaii County and Maui County was upgraded to a hurricane warning, while a hurricane watch was issued for Oahu and Kauai County.[41][22] The hurricane watch for Oahu was upgraded early on August 23 as Lane continued to approach the state.[42] The hurricane warning for Hawaii County was downgraded to a tropical storm warning early on August 24, because hurricane force winds were not expected to occur on the Big Island.[43] Later that day, the hurricane watch for Kauai County was lowered to a tropical storm watch, as Lane was forecasted to weaken to a tropical storm when it passed near the island.[44] Early on August 25, all the hurricane warning was lowered to tropical storm warning after Lane weakened to a tropical storm.[29] Later that day, all watches and warnings were discontinued as Lane weakened and moved away from the islands.[33]

University of Hawaii at Manoa students who were staying on the campus were advised to stay informed and download alert apps, and to store basic emergency supplies such as flashlights, first aid kits, food and water. The University initiated emergency protocols on August 22, and a University spokesperson stated that there was two weeks worth of food and water stored in case of a severe emergency.[45] All school districts statewide closed on August 22 to 24, and all non-essential state employees on the Big Island and Maui were told to stay home for the same duration. Hawaiian Airlines waived the change fees for tickets to, from, within, and through Hawaii from August 21–26.[46] American Airlines, Hawaiian Airlines, and United Airlines cancelled more than two dozen domestic and international flights to and from Honolulu International Airport, Hilo International Airport, Kahului Airport, and Lihue Airport.[47] All commercial harbors in Hilo and Kawaihae suspended operations on August 23, while the remainder of harbors statewide remained one alert level below closure.[48] Numerous state parks and hiking trails closed for the duration of the storm under the threat of flooding and landslides.[49]

As Lane was the first tropical cyclone that threatened to make landfall in Hawaii as a hurricane in over two decades, Fort Shafter announced that all Navy vessels and Air Force planes were being moved out of state on August 22.[50] Vessels and aircraft stationed at Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam, excluding those undergoing maintenance, also relocated. The National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific closed on August 24 and 25 and tours at the USS Arizona Memorial were suspended.[51][52] President Donald Trump issued an emergency declaration for Hawaii. The Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) were authorized to coordinate disaster relief beginning on August 22 and continuing indefinitely.[53] More than 3,900 FEMA personnel were deployed or already in the state to assist with recovery efforts.[54] The Hawaii National Guard placed 280 active duty members—including 120 already responding to the Kilauea volacno—on alert for relief efforts. A further 3,000 personnel from the state's Army National Guard and Air National Guard were available if requested.[55] The Red Cross opened 36 shelters statewide, with 825 people utilizing them by the hurricane's arrival.[56]

Impact

Hawaiʻi

.jpg)

Although Hurricane Lane remained west of the Big Island, tremendous amounts of rain battered eastern areas of the island from August 22 to 26. Hilo saw its wettest three-day period on record with 31.85 in (809 mm) of precipitation observed; 15 in (380 mm) fell on August 24 alone, marking the fifth-wettest day in the city's recorded history.[57] Accumulations were greatest along the volcanic slopes of Mauna Loa; 49.48 in (1,257 mm) fell in Waiākea-Uka near the city.[58] Precipitation peaked at 52.02 in (1,321.3 mm) in Mountain View. This made Lane the wettest tropical cyclone on record in the state of Hawaii, eclipsing the previous peak of 52 in (1,300 mm) during Hurricane Hiki in 1950. A private weather station observed 58.8 in (1,490 mm); however, this value is awaiting verification by meteorologists at the National Weather Service office in Honolulu.[58] Along the still-erupting Kīlauea volcano, the rain created excessive steam that caused whiteouts. Effects on the volcano itself were negligible and limited to minor rockfalls. The porous nature of volcanic rock and land in the Puna District also served to mitigate the amount of runoff.[59]

Flooding closed numerous roads island-wide, including portions of Route 11 and 19 along the Belt Road.[60] Multiple landslides covered portions of the Akoni Pule Highway. In and around Hilo, swollen rivers inundated homes and 100 people required rescue in the Reeds Island subdivision.[57] Six classrooms at Waiakea Elementary School also flooded.[61] Areas along the Hilo Bayfront were particularly affected. Residents in Hawaiian Acres were forced to abandon their cars on flooded roads.[57] Landslides in the town destroyed two homes. Excess water overwhelmed three sewage pumps, causing 9 million gallons of untreated wastewater to spill into Hilo Bay.[62] A small waterspout formed off the coast of Paukaa on August 23.[63] Across Hawaii County, 3 homes were destroyed, 23 homes and 3 businesses suffered major flood damage, while another 113 homes and 17 businesses experienced minor damage.[64] In Kurtistown, a bonsai tree nursery suffered an estimated $3–5 million in property damage with 100 trees lost.[65] Surveys by Hawaii County Civil Defense remained underway as of August 30, 2018.[64]

Maui and Molokaʻi

.jpg)

As the storm passed south of Maui, strong winds downed tree and power lines.[66] Sustained winds reached 44 mph (71 km/h) in Makawao.[67] Some of the lines sparked fires in areas with dry brush, with winds from the hurricane causing them to spread rapidly.[66] The largest of the fires scorched 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) and injured two people, one due to burns and another due to smoke inhalation.[68] Residents observed fire whirls approximately 15 ft (4.6 m) tall.[69] At one point, a hurricane shelter had to be evacuated for encroaching flames while 600 people were evacuated overall.[59][70] The fire destroyed 21 homes, including one worth $5.5 million,[69] leaving 60 people homeless,[68] and burned 27 vehicles.[66] Flames reached the field track at Lahainaluna High School. Once winds from Lane subsided on August 26, firefighters were able to contain the blaze.[68] A second fire ignited near the Lahaina Civic Center,[66] burning 800 acres (3.2 km2) and one home in Kaanapali.[66][68] Twenty-six evacuees staying at Lahaina Intermediate School were forced to relocate due to the fire. The storm left approximately 11,450 customers without electricity across Maui and Molokai, including 4,000 in West Maui.[68] Downed power lines made many evacuated residents slow to return to their homes after the storm.[71]

Heavy rains later affected the island, accumulating to 25.58 in (650 mm) in West Wailuaiki. Hana Airport and Haiku both observed approximately 10.5 in (270 mm) of rain.[58] Precipitation predominately fell on August 25 and aided firefighters in containing the brushfires.[59] Multiple landslides occurred along the Hana Highway.[72] On August 24, a sinkhole estimated to be 25 to 30 ft (7.6 to 9.1 m) deep opened in Haiku. Three residences, each with families home, were left isolated.[73] Infrastructure damage from the sinkhole reached an estimated $2–2.5 million.[66]

Kauaʻi and Oʻahu

Torrential precipitation fell across Kauaʻi between August 27 and 28; accumulations peaked at 34.78 in (883 mm) on Mount Waialeale.[74] Rivers and streams swelled due to heavy rains, especially in the Wainiha and Hanalei Valleys;[74] waters submerged roads and taro (Colocasia esculenta) patches. In Koloa, a man drowned after jumping into a river to save a dog.[75] Water and debris forced road closures along Kūhiō Highway; flooding also affected Hanalei Elementary School and prompted early dismissal of students. Power outages affected households in Haena and Wainiha,[76] with wind gusts in the latter reaching 55 mph (89 km/h).[77] Residents reported similarities to historic flooding in April.[76]

The same rainbands that affected Kauaʻi reached Oʻahu during the morning hours of August 28; rainfall reached 9.81 in (249 mm) in Moanalua. The Kalihi Stream overflowed along the Kamehameha Highway.[74] Brush fires ignited on parts of Oʻahu but were not destructive.[59]

Aftermath

Volunteers from All Hands and Hearts, Team Rubicon, and Southern Baptist Disaster Relief assisted residents with cleaning flood damage and removal of mold.[78] On August 29, the Central Pacific Bank would provide natural disaster loans of $1,000–3,000 for any Maui residents who applied.[66] A brown water advisory was raised for areas between Hāmākua Coast and Laupāhoehoe in Hawaiʻi on September 4 as runoff and sewage spills entered Hilo Bay. Officials advised residents to stay out of coastal waters accordingly.[79][80] On September 6, Governor David Ige requested President Trump declare a major disaster for Hawaii, with damages estimated to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars.[81]

See also

- Other tropical cyclones with the same name

- List of Category 5 Pacific hurricanes

- List of Hawaii hurricanes

- List of wettest tropical cyclones in the United States

- Hurricane Hiki – a hurricane that dropped more than 50 inches (1,300 mm) of rain over areas of Hawaii, in August 1950

- Hurricane Nina (1957) – a hurricane that threatened to make landfall in Kauai, causing significant damage and four deaths, before turning westward out to sea

- Hurricane Dot (1959) – a hurricane that passed south of the Big Island, before curving to the northwest and making landfall in Kauai

- Hurricane Iniki – a Category 4 hurricane in September 1992 that became the costliest tropical cyclone ever to strike Hawaii

- Hurricane Ana – a long-lasting hurricane that took a similar track; first northwards towards Hawaii due to a weakness in a subtropical ridge, then westwards due to westerly trade winds

- Hurricane Olivia (2018) – A Category 4 hurricane that made landfall in Maui and Lanai as a tropical storm, only a few weeks after Hurricane Lane had impacted Hawaii

References

- ↑ Marshall Shepherd (August 22, 2018). "What Experts Are Saying About Rare Category 5 Hurricane Lane Threatening Hawaii". Forbes. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ Berg, Robbie (August 10, 2018). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ↑ Roberts, Dave (August 14, 2018). NHC Graphical Outlook Archive. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (August 15, 2018). Tropical Depression Fourteen-E Advisory Number 1. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Blake, Eric (August 15, 2018). Tropical Storm Lane Discussion Number 3. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (August 17, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 9. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Cangialosi, John (August 17, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 10. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ↑ Roberts, Dave (August 17, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 12. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Roberts, Dave (August 17, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 12. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Beven, Jack (August 18, 2018). "Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 13". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (August 18, 2018). "Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 14". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (August 18, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 14. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (August 18, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 15. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Brown, Daniel (August 18, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 16. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ↑ Powell, Jeff (August 19, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 17. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ↑ Houston, Sam (August 19, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 18. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ↑ Houston, Sam (August 19, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 18. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ↑ Ballard, Richard (August 20, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 24. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ↑ Jacobson, Chris (August 21, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 28. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ Birchard, Tom (August 22, 2018). Hurricane Lane Special Advisory Number 30. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ Harry Cockburn (August 22, 2018). "Hurricane Lane strengthens to a maximum Category 5 cyclone as it bears down on Hawaii". The Independent. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- 1 2 Powell, Jeff (August 22, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 32 (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ↑ Ballard, Robert. Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 37. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ Ballard, Robert (August 24, 2018). Hurricane Lane Intermediate Advisory Number 37A. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ Ballard, Robert (August 23, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 34. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ Houston, Sam (August 24, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 39. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- 1 2 Houston, Sam (August 24, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 40. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ Ballard, Robert (August 25, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 42. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- 1 2 Ballard, Robert (August 25, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 43. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ Ballard, Robert (August 25, 2018). Hurricane Lane Discussion Number 43. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ Houston, Sam (August 25, 2018). Tropical Storm Lane Advisory Number 45. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ↑ Houston, Sam (August 25, 2018). Hurricane Lane Special Advisory Number 43A. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- 1 2 Burke, Bob (August 25, 2018). Tropical Storm Lane Advisory Number 46. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ Birchard, Tom (August 26, 2018). Tropical Depression Lane Advisory Number 49. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ Birchard, Tom (August 27, 2018). Tropical Storm Lane Advisory Number 53. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ↑ Donaldson, Pete (August 28, 2018). Tropical Depression Lane Advisory Number 55. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ↑ Jacobson, Chris (August 28, 2018). Tropical Depression Lane Discussion Number 56. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ↑ Donaldson, Pete (August 29, 2018). Post-Tropical Cyclone Lane Discussion Number 59. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ↑ National Weather Service Office in Honolulu, Hawaii [@NWSHonolulu] (August 31, 2018). "Thanks for pointing this out. The circulation that was associated with Lane dissipated several days ago and was absorbed by the same upper level low responsible for this feature. This feature is now a sub-tropical gale low, but we will continue to keep an eye on it!" (Tweet). Retrieved September 2, 2018 – via Twitter.

- ↑ Tom Birchard (August 21, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 27. Central Pacific Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ↑ Chris Jacobson (August 22, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 29. Central Pacific Hurricane Canter (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ Robert Ballard (August 23, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 34. Central Pacific Hurricane Canter (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ Robert Ballard (August 24, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 38. Central Pacific Hurricane Canter (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ Robert Ballard (August 24, 2018). Hurricane Lane Advisory Number 41. Central Pacific Hurricane Canter (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ Mattison, Sara (August 22, 2018). "UH Manoa students stock up on food, water as Hurricane Lane approaches". KHON. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ Jinnifer Sinco Kelleher (August 22, 2018). "People grab ramen, water as hurricane moves toward Hawaii". KIRO7. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Multiple airlines cancel flights to, from Honolulu and Kahului airports". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. August 24, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ Andrew Gomes (August 23, 2018). "Big Isle ports close, others could follow". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Many Hawaii parks and hiking trails to close in advance of Hurricane Lane". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. August 22, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ Olson, Wyatt. "Navy, Air Force evacuate vessels and aircraft from path of Hawaii-bound hurricane". Stars and Stripes. Defense Media Activity. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ↑ William Cole (August 22, 2018). "Pearl Harbor ships and subs head to sea ahead of Lane". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ William Cole (August 21, 2018). "Arizona Memorial boat tours suspended due to Hurricane Lane". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ "President Donald J. Trump Approves Hawaii Emergency Declaration". Government of the United States. August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ↑ Timothy Hurley (August 31, 2018). "Federal response to Hurricane Lane 'just the beginning'". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ William Cole and Dave Reardon (August 25, 2018). "Active-duty military task force, National Guard ready for Lane". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ Susan Essoyan and Gordon Y.K. Pang (August 24, 2018). "More than 800 people evacuate from hurricane". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Lane's 'catastrophic' flooding leaves behind big mess on Big Island". Hawaii News Now. August 25, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Lane Possibly Breaks Hawaii Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Record (Public Information Statement). National Weather Service Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. August 27, 2018. Archived from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Mark Thiessen (August 26, 2018). "Lane brought record rain to Hawaii, but lost its wallop". Hawaii News Now. Associated Press. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Lane impacts roads across the state". Hawaii News Now. August 25, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ Jennifer Sinco Kelleher (August 27, 2018). "Tropical Storm Lane damage assessment under way". Hawaii News Now. Associated Press. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ Kevin Dayton (August 29, 2018). "Crews fan out to assess storm damage in Hilo". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ "Waterspout forms off Hilo as Hurricane Lane passes Hawaii island". KHON2. August 23, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- 1 2 Kevin Dayton (August 30, 2018). "Reports of flood damage on the rise". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ Callis, Tom. "'If you don't smile you're going to cry': Owner of bonsai nursery laments losses caused by heavy rains". Hawaii Tribune-Herald. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Melissa Tanji (August 29, 2018). "Maui's Lane damage could run up in the millions for repairs". Maui News. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ Preliminary Local Storm Report (Report). National Weather Service Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. August 23, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Firefighters fully contain West Maui wildfires that left significant trail of damage". Hawaii News Now. August 26, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- 1 2 Christie Wilson (August 26, 2018). "Wind-whipped fire ravages Lahaina hillsides, destroys 21 structures". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ Bidgood, Jess (August 24, 2018). "Hurricane Lane Is Downgraded to Tropical Storm, but Hawaii Faces Flooding Threat". New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ↑ "After Lane exits, torrential downpours, renewed flooding a concern in Hawaii". USA TODAY. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ↑ Preliminary Local Storm Report (Report). National Weather Service Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. August 24, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ Young, Pamela (August 28, 2018). "Some Upcountry Maui residents remain stranded by giant sinkhole". KHON. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Final Rain Total from Lane Flood Event on Kauai and Oahu (Report). National Weather Service Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. August 29, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ "1 death from Hawaii storm Lane reported on Kauai". Hawaii News Now. Associated Press. August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- 1 2 "Heavy rain on Kauai's north shore brings back memories of April's historic floods". KHON2. August 27, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ Preliminary Local Storm Report (Report). National Weather Service Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. August 24, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ↑ Stephanie Salmons (September 6, 2018). "Out with 'all the moldy stuff': Volunteers help residents recover from flooding". Hawaii Tribune-Herald. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- ↑ "Brown water advisory posted for some Hawaii Island coastlines". Hawaii News Now. September 4, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ↑ "Health department issues brown-water advisory". Hawaii Tribune-Herald. September 4, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ↑ "Aon Analytics Impact Forecasting Global Catastrophe Recap August 2018" (PDF). Aon Benfield. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Lane (2018). |

- The National Hurricane Center's advisory archive on Hurricane Lane

- The Central Pacific Hurricane Center's advisory archive on Hurricane Lane

![]()