History of the Royal Navy

|

| Her Majesty's Naval Service of the British Armed Forces |

|---|

| Components |

|

|

| History and future |

|

|

| Ships |

| Personnel |

| Auxiliary services |

The official history of the Royal Navy began with the formal establishment of the Royal Navy as the national naval force of the Kingdom of England in 1660, following the Restoration of King Charles II to the throne. However, for more than a thousand years before that there had been English naval forces varying in type and organization. In 1707 it became the naval force of the Kingdom of Great Britain after the Union between England and Scotland which merged the English navy with the much smaller Royal Scots Navy, although the two had begun operating together from the time of the Union of the Crowns in 1603.

Before the creation of the Royal Navy, the English navy had no defined moment of formation; it started out as a motley assortment of "King's ships" during the Middle Ages assembled only as needed and then dispersed, began to take shape as a standing navy during the 16th century, and became a regular establishment during the tumults of the 17th century. The Navy grew considerably during the global struggle with France that started in 1690 and culminated in the Napoleonic Wars, a time when the practice of fighting under sail was developed to its highest point.

The ensuing century of general peace saw considerable technological development, with sail yielding to steam and cannon supplanted by large shell-firing guns, and ending with the race to construct bigger and better battleships. That race, however, was ultimately a dead end, as aircraft carriers and submarines came to the fore and, after the successes of World War II, the Royal Navy yielded its formerly preeminent place to the United States Navy. The Royal Navy has remained one of the world's most capable navies, however, and currently operates a fleet of modern ships.

England and Scotland before 1603

England

The early English kingdoms

Some evidence of English ship construction in the Anglo-Saxon period is available from the boat burials at Snape (about 550) and Sutton Hoo (about 625), though warships would probably have been larger than the vessels interred there. There is little evidence of the naval activities of the English kingdoms before the mid-9th century, but King Edwin of Northumbria (616/7-633/4) conquered the Isle of Man and Anglesey, and another King of Northumbria, Ecgfrith, sent a military expedition to Ireland in 684.[1]

The threat from Vikings increased significantly in the early part of the 9th Century and invasions became a serious menace from about 835.[2] In 851 an unprecedently large force of Danes invaded southern England, carried on about 350 ships. Campaigning inland, this force was decisively defeated by King Æthelwulf of Wessex at the Battle of Aclea, but a naval action was also won by Æthelwulf's son Æthelstan and Ealdorman Ealhere at Sandwich, Kent, capturing nine ships.[3]

The Danish "Great Army" which conquered about half of England during its campaigns in 865-79 operated largely by land, and no naval operations against it by the English kingdoms are recorded. However, in the following years a number of clashes are recorded between Viking raiders and the forces of Alfred the Great, the last remaining English king. These included a victory over four ships by a squadron led by the king himself in 882, and operations against the Danes of East Anglia in 884, which saw an entire Danish squadron of sixteen ships captured by an English force, which was then itself defeated on its way home by another fleet.[4] In 896 Alfred had a number of new ships built to his own design, "nearly twice as long as the others, some having 60 oars, some even more", to counter raids along the south coast.[5] A clash in the Solent later that year saw nine of his new ships defeat six Danish ships.[6]

United England

Naval operations are glimpsed again in 934, when King Æthelstan, now ruler of all England, invaded Scotland with a combined sea and land force.[7] Under King Edgar (959-975) the kings of Scotland, Cumbria and of four other kingdoms would regularly swear to be King Edgar's faithful allies by land and sea.[8]

The renewal of serious Viking attacks in the reign of Æthelred the Unready led to a general muster of ships at London in 992 against the fleet of Olaf Tryggvason, but amid confusion and alleged treachery the English fleet suffered heavy losses. In 1008, Æthelred ordered a new programme of naval construction, under which one warship was to be provided for every 310 hides of land in the kingdom. In 1009 the king took the new fleet out to Sandwich, Kent to guard against the threat of invasion (this port, near the junction of the North Sea and the English Channel and lying within the sheltered offshore anchorage of the Downs, appears frequently in the sources for this period as a position where fleets were stationed on guard). However, this deployment ended in disaster due to internal dissension. Accusations against the great Sussex thegn Wulfnoth (probably the father of Godwin, later Earl of Wessex) led to his flight from the fleet with 20 ships manned by his supporters. A force of 80 ships sent after him was wrecked by a storm and the beached ships burnt by Wulfnoth, after which the remainder of the fleet dispersed in confusion.[9]

English naval forces were supplemented by Scandinavian mercenaries. Directly after the fiasco of 1009 a new invasion force led by the Danish warlord Thorkell the Tall began a devastating campaign in England. When the attackers were finally bought off and dispersed in 1012, Thorkell entered Æthelred's service with 45 ships. When the King of Denmark Swein Forkbeard conquered England in 1013, the fleet remained loyal to Æthelred after the rest of the kingdom had submitted to the invader. Swein's death in 1014 led to Æthelred's brief return to power, but in 1015-16 England was again conquered by Swein's son Cnut, whose invasion force had been joined by 40 ship-loads of Danish mercenaries who defected from Æthelred's service. Having secured the throne, Cnut dismissed the bulk of his fleet, but maintained a standing force of 40 ships, funded by national taxation. In 1025 Cnut led an Anglo-Danish fleet to campaign against his enemies in Scandinavia, and in 1028 he conquered Norway with a force including 50 English ships. The standing fleet was in time reduced to 16 ships, but increased again after Cnut's son Harthacnut brought a fleet from Denmark to claim the throne in 1040.[10]

The early years of Edward the Confessor's reign saw a series of large naval operations under the king's own command, including in 1045 the deployment at Sandwich of a particularly big fleet to guard against an expected invasion from Norway, and a blockade of Flanders in 1049, in support of a land campaign by the German Emperor Henry III. In 1050 Edward reduced the standing force, then numbering 14 ships, to five. After a political crisis in 1051 saw Earl Godwin and his sons driven into exile, Edward sent out a force of 40 ships to Sandwich to guard against their return. However Godwin, returning with ships from Flanders, eluded them, and he and his son Harold, coming from Ireland, gathered a powerful fleet from the "butsecarles" (literally "boatmen") of the Earldom of Wessex. With this fleet and an army also gathered from Wessex, Godwin came to London and confronted the king, who was supported by an army and a fleet of 50 ships. The crisis ended with the negotiated reinstatement of Godwin and his sons to their former possessions and power.[11]

In 1063 Earl Harold Godwinson led a fleet to Wales against Gruffydd ap Llywelyn of Gwynedd, while his brother Tostig invaded by land. Harold put Gruffydd to flight and destroyed his fleet and his residence at Rhuddlan, defeats which led to Gruffydd's murder by his own people in order to end the war. King Edward installed Gruffydd's half-brothers in his place, and they swore to serve him "on water and on land", suggesting that England's native naval forces could be supplemented by tributary contingents from neighbouring dependent territories as well as by foreign mercenaries.[12]

In 1066, following Edward's death and his own election as king, Harold assembled a powerful army and fleet in the Solent to guard against the invasion being prepared by William of Normandy. However, having waited all summer without the Normans appearing, their provisions were exhausted and Harold was forced to dismiss them; many of the ships were wrecked on the way back to London. William was then able to cross unopposed.[13]

After the Norman Conquest

William the Conqueror sent a fleet to Scotland in 1072 but by the early 12th century the fleet had almost disappeared. Yet in 1141 Henry II invaded Ireland while a fleet of 167 ships sailed from Dartmouth on a crusade to capture Lisbon from the Moors. A further fleet was raised for the Third Crusade in 1190. The Norman kings had a regular need for cross-Channel transport and raised a naval force in 1155, with the Cinque Ports required to provide a total of 57 ships crewed by 21 sailors apiece. However, with the loss of Normandy by King John (who even so had a fleet of 500 sail in an attempt to regain it), this had to become a force capable of preventing invasion (e.g. the 1215–1217 French invasion of England) and protecting traffic to and from Gascony. In the first years of the 13th century William de Wrotham appears in the records as the clerk of a force of galleys to be used against Philip Augustus of France. In 1206 King John ordered 54 royal galleys to be constructed and between 1207 and 1211 £5000 was spent on the royal fleet. The fleet also started to have an offensive capability, as in 1213 when ships commanded by the Earl of Salisbury raided Damme in Flanders, where they burned many ships of the French fleet.[14]

An infrastructure was also developing—by 1212 a base existed at Portsmouth, supporting at least ten ships. Later in the 13th century ships begin to be mentioned regularly as support for various campaigns under Edward I, most notably in Luke de Tany's capture of Anglesey in 1282. Edward II of England attempted to blockade Scotland, but ineffectively. Naval expenses were considerable, with twenty 120-oared galleys being ordered in 1294 because of a fear of French invasion. In 1224 the first Admiral of England is recorded in charters with Henry III granting the title to Sir Richard de Lucy.[15] Four other men were granted the same title but styled differently, they were in 1263 Sir Thomas de Moleton as Captain and Guardian of the English Seas and in 1286 Sir William de Leybourne, as Admiral of the English Seas both of these offices were granted by King Edward I. In 1321 Sir Richard de Leyburn is granted the title Admiral of England, Wales and Ireland, by Edward II and Sir John de Beauchamp, 1st Baron Beauchamp de Warwick, as High Admiral of England the office granted by Edward III in 1360. Although each holding the title of Admiralis Angliae the civil jurisdiction of their offices was never used nor did they officially receive letters patent from the monarch.[15]

In 1321 Sir John de Beauchamp, 1st Baron Beauchamp de Warwick is also appointed Admiral of the South, North and West effectively the English Navy's first Admiral of the Fleet.[16] The first Admiral to be granted a patent by the monarch was Richard FitzAlan, 10th Earl of Arundel as High Admiral of England, Ireland and Aquitaine given by King Richard III in 1385 .[17] In the early 13th century English Admirals tended to be knights or barons and their role was essentially administrative not operational. In 1294 Edward I divided the English Navy into three geographical 'admiralties' each assigned a fleet and each of them administered by an admiral,[18] they were the Admiral of the Northern Fleet, Admiral of the Western Fleet and Admiral of the Southern Fleet, each was responsible for managing and enforcing admiralty jurisdiction in their respective areas and raising and administering the ships. It also allowed Edward I to mount expeditions to Brittany, Flanders or Scotland with greater ease.[19]

The Hundred Years' War (1337–1453) included frequent cross-Channel raids, frequently unopposed due to the lack of effective communications and the limitations of naval organisation. The navy was used for reconnaissance as well as attacks on merchantmen and warships. Prize ships and cargos were shared out. The Battle of Sluys in 1340 was a significant English victory, with Edward III of England's 160 ships (mostly hired merchant vessels) assaulting a French force in the Zwyn estuary and capturing 180 French ships in hand-to-hand combat. Les Espagnols sur Mer, fought in the Channel off Winchelsea in 1350, is possibly the first major battle in the open sea in English history; the English captured 14 Spanish ships. The 14th century also saw the creation of the post of Clerk of the King's Ships, who appears from 1344 on as in charge of some 34 royal vessels. At one point in the mid-fourteenth century Edward III's navy overall had some 700 ships in service.[20] In 1364 the Northern and Western admiralities and fleets are combined commanded by the Admiral of the North and West, and remain so on an adhoc basis until 1414.[21]

English fortunes declined in the 1370s, with merchants objecting to the continual borrowing of their ships. There was objection to the taxation to man the king's ships, and by the end of the reign of Richard II of England only four were left, and by 1409 only two. Henry V of England revived the navy, building a number of balingers and "great ships", increasing the fleet from six in 1413 to 39 in 1417/8. This included the 1,400-ton Grace Dieu (which still exists, buried in the Hamble estuary), and won victories in the Channel, reaching a high point in 1417 when the French fleet was destroyed. An invasion of France took place in 1415 which led to the capture of Harfleur and the victory at Agincourt. A second invasion, beginning in 1419, led to the conquest of the Channel coast of France, almost eliminating any seaborne threat to England and enabling the running-down of Henry's naval forces.[22]

Dealing with the matter of naval administration during the 15th century the most significant development was the establishment of the first Admiralty of England this was brought about in 1412 when the remaining geographic 'admiralties' the Northern Admiralty and Western Admiralty were abolished and their functions were unified under a single administrative and operational command the Admiralty Office later called the Admiralty and Marine Affairs Office.[23]

Significant new construction did not occur until the 1480s, by which time ships mounted guns regularly; the Regent of 1487 had 225 serpentines, an early type of cannon. Henry VII deserves a large share of credit in the establishment of a standing navy. Although there is no evidence for a conscious change of policy, Henry soon embarked on a program of building ships larger than heretofore. He also invested in dockyards, and commissioned the oldest surviving dry dock in 1495 at Portsmouth.[24]

The beginnings of an organized English navy, 1485–1603

Henry VIII ordered a major expansion of the fleet, which increased from five ships in 1509 to thirty in 1514 including the Henri Grâce a Dieu ("Great Harry") of 1500 tons and Mary Rose of 600 tons. Most of the fleet was laid up after 1525 but, because of the break with the Catholic Church, 27 new ships were built with money from the sale of the monasteries as well as forts and blockhouses. In 1544 Boulogne was captured. The French navy raided the Isle of Wight and was then fought off in the Battle of the Solent in 1545, prior to which Mary Rose sank.[25]

A detailed and largely accurate contemporary document, The Anthony Roll, was written in 1540. It gave a nearly complete account of the English navy, which contained roughly 50 ships, including carracks, galleys, galleasses and pinnaces. The carracks included famous vessels such as the Mary Rose, the Peter Pomegranate and the Henry Grace à Dieu.[26]

In 1580 Spanish and Portuguese troops were sent to Ireland but were defeated by an English army and naval force.[27]

In the 1550s English gentlemen opposed to the Catholicism of Philip and Mary took refuge in France and were active in the English Channel as privateers under letters of marque from the French king. Six of their vessels were captured off Plymouth in July 1556.[28]

In the late 16th century the Spanish Empire, at the time Europe's superpower and the leading naval power of the 16th century, threatened England with invasion to restore Catholicism in England. Francis Drake attacked Cadiz and A Coruña to delay the attack. The Spanish Armada finally set sail in 1588 to enforce Spain's dominance over the English Channel and transport troops from the Spanish Netherlands to England. The Spanish plan failed due to maladministration, logistical errors, blocking actions by the Dutch, bad weather, and the significant defeat by the English at the naval Battle of Gravelines. However, the bungled Drake-Norris Expedition of 1589 and the more successful raid by Lord Howard in 1596 prevented further invasion plans from occurring. A blockade of the Spanish coast was undertaken by John Hawkins and Martin Frobisher in 1590. Under the reign of Elizabeth I England raided Spain's ports and attacked Spanish ships crossing the Atlantic Ocean, capturing much treasure.[29]

While Henry VIII had launched the Royal Navy, his successors King Edward VI and Queen Mary I had ignored it and it was little more than a system of coastal defence. Elizabeth made naval strength a high priority.[28][30] She risked war with Spain by supporting the "Sea Dogs", such as John Hawkins and Francis Drake, who preyed on the Spanish merchant ships carrying gold and silver from the New World. The Navy yards were leaders in technical innovation, and the captains devised new tactics. Parker (1996) argues that the full-rigged ship was one of the greatest technological advances of the century and permanently transformed naval warfare. In 1573 English shipwrights introduced designs, first demonstrated in the "Dreadnaught", that allowed the ships to sail faster and maneuver better and permitted heavier guns.[31] Whereas before warships had tried to grapple with each other so that soldiers could board the enemy ship, now they stood off and fired broadsides that would sink the enemy vessel. When Spain finally decided to invade and conquer England it was a fiasco. Superior English ships and seamanship foiled the invasion and led to the destruction of the Spanish Armada in 1588, marking the high point of Elizabeth's reign. Technically, the Armada failed because Spain's over-complex strategy required coordination between the invasion fleet and the Spanish army on shore. But the poor design of the Spanish cannons meant they were much slower in reloading in a close-range battle, allowing England to take control. Spain and France still had stronger fleets, but England was catching up.[32][33]

Scotland

The Royal Scots Navy (or Old Scots Navy) was the navy of the Kingdom of Scotland until its merger with the Kingdom of England's Royal Navy in 1707 as a consequence of the Treaty of Union and the Acts of Union that ratified it. From 1603 until 1707, the Royal Scots Navy and England's Royal Navy were organised as one force, though not technically merged, as a consequence of the Union of the Crowns when James VI of Scotland became King of England also, as James I.[34]

Though the Lord of the Isles had a large fleet of galleys in the 13th and 14th centuries, there appears little or no trace of a Scots navy during the Wars of Scottish Independence. With Scottish independence established, Robert the Bruce turned his attention to the upbuilding of Scots shipping and of a Scots navy. In his later days he visited the Western Isles, which was part of the domain of the powerful Lords of the Isles who owed only a loose allegiance to him, and established a royal castle at East Loch Tarbert in Argyll to overawe the semi-independent Islemen. The Exchequer Rolls of 1326 record the feudal services of certain of his vassals on the western coast in aiding him with their vessels and crews. This process probably began in the thirteenth century, but would be intensified under Robert.[35]

15th century expansion

In the 15th century, James I gave close attention to the shipping interests of his country, establishing a shipbuilding yard, a house for marine stores, and a workshop at Leith. In 1429 James went to the Western Isles with one of his ships to curb his vassals there. In the same year Parliament enacted a law that each four merk land on the north and west coasts of Scotland within six miles of the sea was, in feudal service to the king, to furnish one oar. This was the nearest approach ever made in Scotland to the ship money of England. His successor, James II, developed the use of gunpowder and artillery. James III and James IV continued to build up the navy, with James III having 38 ships built for the fleet and founding two new dockyards. In addition, the Scots Parliaments passed legislation in 1493 and 1503 requiring all seaboard burghs to keep "busches" of 20 tons to be manned by idle able-bodied men.[36]

James IV succeeded in building up a navy that was truly royal. Dissatisfied with sandbanks at Leith, James himself sited a new harbour at Newhaven in May 1504, and two years later ordered the construction of a dockyard at the Pools of Airth. The upper reaches of the Forth were protected by new fortifications on Inchgarvie.[37] His greatest achievement was the construction of Great Michael, the largest ship up to that time launched in Scotland, the building of which cost £30,000. Work on the ship commenced in 1506, first launched on 11 October 1511 at Newhaven, she sailed up the Forth to Airth for further fitting. The Michael weighed 1,000 tons, was 240 feet (73 m) in length, was manned by 1,000 seamen and 120 gunners and was then the largest ship in Europe (according to the chronicler Lindsay of Pitscottie). In 1514 the Great Michael was sold to France for 40,000 francs tournais.[38]

Neglect and eventual merger

The Scottish Reformation in 1560 established a government that was friendly to England and this resulted in less military necessity to maintain a fleet of great ships. With the Union of the Crowns in 1603, the incentive to rebuild a separate royal fleet for Scotland diminished further since James VI now controlled the powerful English Royal Navy, which could send ships north to defend Scottish interests, and which now opened its ranks to Scottish officers.[39]

From 1603 until union with England in 1707, Scotland and England continued to have separate navies, though they operated as one force. Thomas Gordon became the last commander of the Royal Scots Navy, taking charge of HMS Royal Mary on the North Sea patrol, moving to Royal William when she entered service in 1705, and being promoted to commodore in 1706. With the Act of Union in 1707, the Royal Scottish Navy was merged with the English Royal Navy, but there were already much larger English ships called Royal William and Mary, so the Scottish frigates were renamed HMS Edinburgh and HMS Glasgow, while only HMS Dumbarton Castle retained its name.[40]

The development of the single British navy

After 1603 the English and Scottish fleets were organized together under James I but the efficiency of the Navy declined gradually, while corruption grew until brought under control in an inquiry of 1618. James concluded a peace with Spain and privateering was outlawed. Notable construction in the early 17th century included the 1,200-ton HMS Prince Royal, the first three-decker, and HMS Sovereign of the Seas in 1637, designed by Phineas Pett. Operations under James I did not go well, with expeditions against Algerian pirates in 1620/1, Cadiz in 1625, and La Rochelle in 1627/8 being expensive failures.[41]

Expansion of the fighting force, 1642–1689

Charles I levied "ship money" from 1634 and this unpopular tax was one of the main causes of the first English Civil War from 1642–45. At the beginning of the war the navy, then consisting of 35 vessels, sided with Parliament. During the war the royalist side used a number of small ships to blockade ports and for supplying their own armies. These were afterwards combined into a single force. Charles had surrendered to the Scots and conspired with them to invade England during the second English Civil War of 1648–51. In 1648 part of the Parliamentary fleet mutinied and joined the Royalist side. However, the Royalist fleet was driven to Spain and destroyed during the Commonwealth period by Robert Blake. The execution of Charles I forced the rapid expansion of the navy, by multiplying England's actual and potential enemies, and many vessels were constructed from the 1650s onward. This reformation of the navy was also carried out by Blake.[42]

The Navigation Act 1651 cut out Dutch shippers from English trade. Operations of the late 17th century were dominated by the three Anglo-Dutch Wars, which stretched from 1652 to 1674. Forty new ships were built between 1650 and 1654. Triggered by seemingly trivial incidents, but motivated by economic competition, they were notable as purely naval wars fought in the English Channel and the North Sea. In February 1653 the English Channel was closed to Dutch ships which were then forced back to their home ports.[43]

(Jan_Abrahamsz._Beerstraten).jpg)

The Interregnum saw a considerable expansion in the strength of the navy, both in number of ships and in internal importance within English policy. The Restoration Monarchy inherited this large navy and continued the same policy of expansion of the navy, focusing on making a strong navy full of large ships in order to provide a strong defence under Charles II.[44] At the start of the Restoration, Parliament listed forty ships of the Royal Navy (not of the Summer's Guard) with a complement of 3,695 sailors.[45]

The administration of the navy was greatly improved by Sir William Coventry and Samuel Pepys, both of whom began their service in 1660 with the Restoration. While it was Pepys' diary that made him the most famous of all naval bureaucrats, his nearly thirty years of administration were crucial in replacing the ad hoc processes of years past with regular programmes of supply, construction, pay, and so forth. He was responsible for introduction of the "Navy List" which fixed the order of promotion. In 1683 the "Victualling Board" was set up which fixed the ration scales. In 1655 Blake routed the Barbary pirates and started a campaign against the Spanish in the Caribbean, capturing Jamaica.[46]

In 1664 the English captured New Amsterdam (later New York City) resulting in the Second Dutch War (1665–1667). In 1666 the Four Days Battle was a defeat for the English but the Dutch fleet was crushed a month later off Orfordness. In 1667 the Dutch mounted the Raid on the Medway, breaking into Chatham Dockyard and capturing or burning many of the Navy's largest ships at their moorings,[47] which resulted in the most humiliating defeat in the Royal Navy's history.[48] The English were also defeated at Solebay in 1672. The experience of large-scale battle was instructive to the Navy; the Articles of War regularizing the conduct of officers and seaman, and the "Fighting Instructions" establishing the line of battle, both date from this period.[49] The influence and reforms of Samuel Pepys, the Chief Secretary to the Admiralty under both King Charles II and subsequently King James II, were important in the early professionalisation of the Royal Navy.[50]

Wars with France, Spain and America, 1690–1793

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 rearranged the political map of Europe, and led to a series of wars with France that lasted well over a century. This was the classic age of sail; while the ships themselves evolved in only minor ways, technique and tactics were honed to a high degree, and the battles of the Napoleonic Wars entailed feats that would have been impossible for the fleets of the 17th century. Because of parliamentary opposition, James II fled the country. The landing of William III and the Glorious Revolution itself was a gigantic effort involving 100 warships and 400 transports carrying 11,000 infantry and 4,000 horses. It was not opposed by the English or Scottish fleets. Louis XIV declared war just days later, a conflict which became known as the War of the Grand Alliance. The English defeat at the Battle of Beachy Head of 1690 led to an improved version of the Fighting Instructions, and subsequent operations against French ports proved more successful, leading to decisive victory at La Hougue in 1692.[51]

Naval operations in the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–13) were with the Dutch against the Spanish and French. They were at first focused on the acquisition of a Mediterranean base, culminating in an alliance with Portugal and the capture of Gibraltar (1704) and Port Mahon in Minorca (1708). In addition Newfoundland and Nova Scotia were obtained. Even so, freedom of action in the Mediterranean did not decide the war, although it gave the new Kingdom of Great Britain (created by the Union of England and Scotland in 1707) an advantage when negotiating the Peace of Utrecht, and made Britain a recognized great power. Spanish treasure fleets were sunk in 1704 and 1708, and the Spanish Empire was opened up to British slaving voyages. The British fleet ended Spanish occupation of Sicily in 1718 and in 1727 blockaded Panama.[52]

The subsequent quarter-century of peace saw a few naval actions. The navy was used against Russia and Sweden in the Baltic from 1715 to 1727 to protect supplies of naval stores. It was used at the Cape Passaro in 1718, during the Great Northern War, and in the West Indies (1726). There was a war against Spain in 1739 over the slave trade. In 1745 the navy contributed to collapse of the Jacobite rising.[53]

The War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–48) saw various naval operations in the Caribbean under admirals Vernon and Anson against Spanish trade and possessions, before the war subsequently merged into the wider War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). This, in turn, brought a new round of naval operations against France, including a blockade of Toulon. In 1747 the navy twice defeated the French off Finisterre.[54]

The Seven Years' War (1756–63) began somewhat inauspiciously for the Navy, with a French siege of Minorca and the failure of Admiral John Byng to relieve it; he was executed on his own quarterdeck. Voltaire famously wrote, in reference to Byng's execution, that "in this country it is wise to kill an admiral from time to time to encourage the others" (admirals). (Today the French phrase "pour encourager les autres" used in English euphemistically connotes a threat by example.) Minorca was lost but subsequent operations went more successfully (due more to government support and better strategic thinking, rather than admirals "encouraged" by Byng's example), and the British fleet won several victories. The French tried to invade Britain in 1759 but their force was defeated at Quiberon Bay off the coast of Brittany. Spain entered the war against Britain in 1762 but lost Havana and Manila, though the latter was given back in exchange for Florida. The Treaty of Paris ended the war.[55]

At the beginning of the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), the Royal Navy dealt with the fledgling Continental Navy handily, destroying or capturing many of its vessels. However, France soon took the American side, and in 1778 a French fleet sailed for America, where it attempted to land at Rhode Island and nearly engaged with the British fleet before a storm intervened, while back home another fought the British in the First Battle of Ushant. Spain and the Dutch Republic entered the war in 1780. Action shifted to the Caribbean, where there were a number of battles with varying results. A Spanish fleet was defeated at the battle of Cape Saint Vincent in 1780 while a Franco-Spanish fleet was defeated in the West Indies in 1782. The most important operation came in 1781 when, in the Battle of the Chesapeake, the British failed to lift the French blockade of Lord Cornwallis, resulting in a British surrender in the Battle of Yorktown. Although combat was over in North America, it continued in the Caribbean (Battle of the Saintes) and India, where the British experienced both successes and failures. Though Minorca had been recaptured, it was returned to the Spanish.[56]

French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815)

The French Revolutionary Wars of 1793–1802 and the Napoleonic Wars of 1803–15 saw the Royal Navy reach a peak of efficiency, dominating the navies of all Britain's adversaries. Initially Britain did not involve itself in the French Revolution, but in 1793 France declared war, leading to the Glorious First of June battle in the following year off Brest, followed by the capture of French colonies in the Caribbean. The Dutch Republic declared war in 1795 and Spain in 1796, on the side of France. Further action came in 1797 and 1798, with the Battle of Cape St Vincent and the Battle of the Nile (also known as the Battle of Aboukir Bay), which brought Admiral Horatio Nelson to the public's attention. The latter engagement cut off Napoleon's expedition to Egypt, though French forces remained in control of that country for three more years. In 1800 Russia, Sweden and Denmark agreed to resist British warships searching neutral shipping for French goods and in 1801 the Danes closed their ports to British shipping. This caused Britain to attack ships and the fort at the Battle of Copenhagen.[57]

The Peace of Amiens in 1802 proved to be but a brief interruption in the years of warfare, and the Navy was soon blockading Napoleon's France. In 1805 French invasion forces were massed on the French coast with 2,300 vessels. The French fleet at Toulon went to the West Indies where it was intended to meet the Spanish one but it was chased by the British fleet and returned without meeting up. After fighting an action off Finisterre the French fleet withdrew to Cadiz where it met up with the Spanish one. The height of the Navy's achievements came on 21 October 1805 at the Battle of Trafalgar where a numerically smaller but more experienced British fleet under the command of Admiral Lord Nelson decisively defeated the combined French and Spanish fleet. The victory at Trafalgar consolidated the United Kingdom's advantage over other European maritime powers, but Nelson was killed during the battle.[58]

By concentrating its military resources in the navy, Britain could both defend itself and project its power across the oceans as well as threaten rivals' ocean trading routes. Britain therefore needed to maintain only a relatively small, highly mobile, professional army that sailed to where it was needed, and was supported by the navy with bombardment, movement, supplies and reinforcement. The Navy could cut off enemies' sea-borne supplies, as with Napoleon's army in Egypt.[59]

Theoretically, the highest commands of the Royal Navy were open to all within its ranks showing talent. In practice, family connections, political or professional patronage were very important for promotion to ranks higher than Commander.[60] British captains were responsible for recruiting their ship's crew from a combination of volunteers, impressment and the requisitioning of existing crew members from ships in ordinary. From 1795 a Quota System was also applied, where each British county was required to supply a certain number of volunteers. Many nationalities served on British ships, with foreigners comprising fifteen per cent of crews by the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Americans were the most common foreign nationality in naval service, followed by Dutch, Scandinavian and Italian.[61] While most foreigners in the Navy were obtained through impressment or from prison ships, around 200 captured French sailors were also persuaded to join after their fleet was defeated at the Battle of the Nile.[61]

The conditions of service for ordinary seamen, while poor by modern standards, were better than many other kinds of work at the time. However, inflation during the late 18th century eroded the real value of seamen's pay while, at the same time, the war caused an increase in pay for merchant ships. Naval pay also often ran years in arrears, and shore leave decreased as ships needed to spend less time in port with better provisioning and health care, and copper bottoms (which delayed fouling). Discontent over these issues eventually resulted in serious mutinies in 1797 when the crews of the Spithead and Nore fleets refused to obey their officers and some captains were sent ashore. This resulted in the short-lived "Floating Republic" which at Spithead was quelled by promising improvements in conditions, but at the Nore resulted in the hanging of 29 mutineers. It is worth noting that neither of the mutinies included flogging or impressment in their list of grievances and, in fact, the mutineers themselves continued the practice of flogging to preserve discipline.[62]

Napoleon acted to counter Britain's maritime supremacy and economic power, closing European ports to British trade. He also authorised many privateers, operating from French territories in the West Indies, placing great pressure on British mercantile shipping in the western hemisphere. The Royal Navy was too hard-pressed in European waters to release significant forces to combat the privateers, and its large ships of the line were not very effective at seeking out and running down fast and manoeuvrable privateers which operated as widely spread single ships or small groups. The Royal Navy reacted by commissioning small warships of traditional Bermuda design. The first three ordered from Bermudian builders—HMS Dasher, HMS Driver and HMS Hunter—were sloops of 200 tons, armed with twelve 24-pounder guns. A great many more ships of this type were ordered, or bought from trade, primarily for use as couriers. The most notable was HMS Pickle, the former Bermudian merchantman that carried news of victory back from Trafalgar.[63]

Although brief in retrospect, the years of the Napoleonic wars came to be remembered as the apotheosis of "fighting sail", and stories of the Royal Navy at this period have been told and retold regularly since then, most famously in the Horatio Hornblower series of C. S. Forrester.[64]

War of 1812

In the years following the battle of Trafalgar there was increasing tension at sea between Britain and the United States. American traders took advantage of their country's neutrality to trade with both the French-controlled parts of Europe, and Britain. Both France and Britain tried to prevent each other's trade, but only the Royal Navy was in a position to enforce a blockade. Another irritant was the suspected presence of British deserters aboard US merchant and naval vessels. Royal Navy ships often attempted to recover these deserters. In one notorious instance in 1807, otherwise known as the Chesapeake–Leopard Affair, HMS Leopard fired on USS Chesapeake causing significant casualties before boarding and seizing suspected British deserters.[65]

In 1812, while the Napoleonic wars continued, the United States declared war on the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and invaded Canada. Occupied by its struggle with France, British policy was to commit only sufficient forces to the American War of 1812 to prevent American victory. On land, this meant a great reliance on militia and Native American allies. On the water, the Royal Navy kept its large men-of-war in Europe, relying on smaller vessels to counter the weak United States Navy. Some of the action consisted of small-scale engagements on the Great Lakes.[66]

A key element of the war was the battle for control of the Great Lakes. Without the support of ships to move soldiers, equipment and supplies, either side would be at a great disadvantage, especially against an enemy who was able to make full use of the lakes. All of the Royal Naval vessels on Lake Erie were captured at the decisive Battle of Lake Erie on 10 September 1813. The British Army, along with militia and Indian units, was now cut off from supplies and retreated eastward. They were caught and defeated at the Battle of the Thames on 5 October 1813, which gave Americans the control over western Ontario, and destroyed the Indian alliance the British Army had depended upon. In 1814 the British Army, bringing in veteran units from the Peninsular War, launched a major invasion of New York State under General Sir George Prévost. However, the supporting Royal Navy vessels on Lake Champlain were sunk by the American fleet at the Battle of Plattsburgh on 11 September 1814, forcing Prévost to retreat back to Canada despite his much larger army.[67]

At sea, the War of 1812 was characterised by single-ship actions between small ships, and disruption of merchant shipping. The Royal Navy struggled to build as many ships as it could, generally sacrificing on the size and armament of vessels, and struggled harder to find adequate personnel, trained or barely trained, to crew them. Royal Naval vessels were often under-manned, without sufficient men to fire a full broadside. Many of the men crewing Royal Naval vessels were rated only as landsmen, and many of those rated as seamen were impressed (conscripted), with resultingly poor morale. The US Navy could not begin to equal the Royal Navy in number of vessels, and had concentrated in building a handful of better-designed frigates. These were larger, heavier and better-armed (both in terms of number of guns, and in the range to which the guns could fire) than their British counterparts, and were handled well by larger volunteer crews (where the Royal Navy was hindered by a relative shortage of trained seamen, the US Navy was not large enough to make full use of the large number of American merchant seamen put out of work, even before the war, by the Embargo Act). As a result, a significant number of British ships were defeated and, midway through the war, the Admiralty issued the order not to engage American frigates individually.[68]

There were also significant losses of merchant shipping to American privateers, a total of 1,300 vessels;[69][70] however, the Royal Navy, operating from its new base and dockyard, off the US Atlantic Seaboard in Bermuda, gradually reinforced the blockade of the American coast, virtually halting all trade by sea, capturing many merchant ships, and forcing the US navy frigates to stay in harbour or risk being captured. Despite successful American claims for damage having been pressed in British courts against British privateers several years before, the War was probably the last occasion on which the Royal Navy made considerable reliance on privateers to boost Britain's maritime power. In Bermuda, privateering had thrived until the build-up of the regular Royal Naval establishment, which began in 1795, reduced the Admiralty's reliance on privateers in the Western Atlantic. During the American War of 1812, however, Bermudian privateers alone captured 298 enemy ships (the total captures by all British naval and privateering vessels between the Great Lakes and the West Indies was 1,593 vessels.)[71]

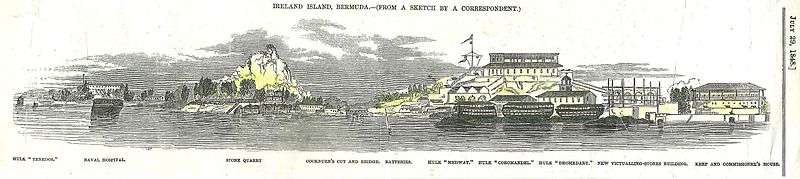

By this time, the Royal Navy was building a naval base and dockyard in Bermuda. It had begun buying land, mostly at the West End of Bermuda, notably Ireland Island, following American independence, permanently establishing itself in the colony in 1795. The development of the intended site was delayed by a dozen years as a suitable passage through the surrounding reefline needed to be located. Until then, the Royal Navy operated from the old capital in the East End, St. George's. Bermuda replaced Newfoundland initially as the winter base of the North America and West Indies Squadron, and then as its year-round headquarters, naval station, and dockyard, with its Admiralty House at Mount Wyndham, in Bailey's Bay, and then at Spanish Point, opposite Ireland Island on the mouth of Great Sound.[72]

Located 1,030 kilometres (640 mi) off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, 1,239 kilometres (770 mi) South of Cape Sable Island, Nova Scotia, and 1,770 kilometres (1,100 mi) North-East of Miami, Bermuda replaced the continental bases between Canada and the West Indies that the Royal Navy had been deprived of by American independence. During the War of 1812 the Royal Navy's blockade of the US Atlantic ports was coordinated from Bermuda and Halifax, Nova Scotia.[73]

The blockade kept most of the American navy trapped in port. The Royal Navy also occupied coastal islands, encouraging American slaves to defect. Military-aged males were enlisted into a Corps of Colonial Marines while their families were sent to the dockyard in Bermuda for the duration of the war, employed by the Royal Navy. These marines fought for the Crown on the Atlantic Seaboard, and in the attack on Washington, D.C. and the Chesapeake.[74]

After British victory in the Peninsular War, part of Wellington's Light Division was released for service in North America. This 2,500-man force, composed of detachments from the 4, 21, 44, and 85 Regiments with some elements of artillery and sappers and commanded by Major-General Ross, arrived in Bermuda in 1814 aboard a fleet composed of the 74-gun HMS Royal Oak, three frigates, three sloops and ten other vessels. The combined force was to launch raids on the coastlines of Maryland and Virginia, with the aim of drawing US forces away from the Canada–US border. In response to American actions at Lake Erie (the Burning of York), however, Sir George Prevost requested a punitive expedition which would "deter the enemy from a repetition of such outrages". The British force arrived at the Patuxent on 17 August and landed the soldiers within 36 miles of Washington, D.C.. Led by Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn, the British force drove the US government out of Washington, D.C.. Ross shied from the idea of burning the city, but Cockburn and others set it alight. Buildings burned included the US Capitol and the US President's Mansion.[75]

Pax Britannica, 1815–1895

After 1827 there were no major battles until 1914. The navy was used against shore installations, such as those in the Baltic and Black Sea in 1854 and 1855, to fight pirates; to hunt down slave ships; and to assist the army when sailors and marines were landed as naval brigades, as on many occasions between the siege of Sebastopol and the 1900 Boxer Rebellion. With a fleet larger than any two rivals combined, the British nation could take security for granted, but at all times the national leaders and public opinion supported a powerful navy, and service was of high prestige.[76]

Operations

The first action of the period was the bombardment of Algiers under Lord Exmouth, conducted in 1816. This was to force the freeing of Christian slaves.[77] During the Greek War of Independence, at the Battle of Navarino in 1827, the Turkish fleet was destroyed by the combined fleets of Britain, France and Russia. This was the last major action between fleets of sailing ships.[78] Ottoman involvement continued, with the bombardment of Acre in 1840, and additional Mediterranean crises during the rest of the decade.[79]

To try to prevent Russia gaining access to a warm water port, the Crimean War was fought in the 1850s. Britain (in concert with the Turks and French) sent 150 transports and 13 warships and the Russian Black Sea fleet was destroyed. The Crimean War became known as a testing ground for the new technologies of steam and shell. It was shown that explosive shells ripped wooden hulls to pieces, which led to the development of the "iron clad" ship. It also showed the need for a permanent pool of trained seamen. There were two Anglo-French campaigns against Russia. In the Black Sea, success at Sevastopol was paralleled by successful operations in the Baltic including the bombardments of Bomarsund and Sveaborg.[80]

The Chinese government placed unilateral restraints on British trade with China. In 1839 a Chinese official impounded opium from India, but the British insisted on the British Empire being allowed to export to China and instituted a blockade of Canton, beginning the First Opium War. There was a Second Opium War from 1856 to 1860. In 1857 the British captured Canton and threatened Beijing, thrown back by the Chinese in 1859 but succeeding the following year. As a result of these actions Britain gained a base at Hong Kong in 1839 and a base in Canton in 1857.[81]

In 1864 the bombardment of Kagoshima forced Japan to accept foreign traders.[82] During the Russo-Turkish War the British sent a fleet of battleships under Admiral Geoffrey Hornby to intimidate Russia from entering Constantinople.[83] Over the next thirty years, only a bombardment of Alexandria in 1882 brought the fleet into action, carried out to ensure control of the Suez Canal.[84]

Technology

Steam power was of interest to the Royal Navy from the beginning of the 19th century, since it neatly solved the difficult and dangerous sailing problems encountered in estuaries and other inshore areas. It was first adopted in the HMS Comet of 1821, and in 1824 HMS Lightning accompanied the expedition to Algiers. Steam vessels appeared in greater numbers through the 1830s and 1840s, all using side-mounted paddlewheels; screw propellers were introduced in the 1830s and, after some reluctance, were adopted in the mid-1840s (the famous tug-of-war between the screw-propelled HMS Rattler and the paddlewheeled Alecto (1839) was entertaining, but records show the Admiralty had already decided on and ordered screw ships). The first major steam warship was HMS Agamemnon. In the 1850s Naval Arms Race screw battleships and frigates, both conversions and new constructions, were built in large numbers. These ships retained a full capacity for sail as steam engines were not yet efficient enough to permit long ocean voyages under power. Steam power was intended only for use during battle and to allow ships to go to sea at will instead of being held in port by adverse winds. A triple expansion steam engine was introduced in 1881 which was more efficient than earlier ones.[85]

Iron in ship construction was first used for diagonal-cross-bracing in major warships. The adoption of iron hulls for ocean-going ships had to wait until after Admiralty experiments had solved the problem of an iron-hull's effect on compass deviation. Because iron hulls were much thinner than wooden hulls, they appeared to be more vulnerable to damage when ships ran aground. Although Brunel had adopted iron in the Great Britain, the Admiralty was also concerned about the vulnerability of iron in combat, and experiments with iron in the 1840s seemed to indicate that iron would shatter under impact.[86]

In 1858 France built the first seagoing ironclad, Gloire, and Britain responded with Warrior of 1860, the first of the 1860s Naval Arms Race—an intensive programme of construction that eclipsed French efforts by 1870. She was called a "Black Snake" by Napoleon III, but was soon superseded.[87]

When armoured ships were first introduced, in-service guns had very little ability to penetrate their armour. However, starting in 1867, guns started to be introduced into service capable of penetrating the armour of the first generation iron-clads, albeit at favourable angles and at short range. This had already been anticipated, and armour thicknesses grew, resulting in turn in a gun calibre-race as larger guns gave better penetration. The explosive shell was introduced in 1820.[88]

In parallel with this there was a debate over how guns should be mounted on ship. Captain Cowper Coles had developed a turret design in the late-1850s as a result of experience in the Crimean War. Initial designs, published in Blackwood's Magazine in 1859 were for a ship with far more than 10 turrets. Consequently, a range of coastal-service turret-ships were built in parallel with the seagoing iron-clads. Because of agitation from Captain Coles and his supporters, the issue of turret-ships became deeply political, and resulted in the ordering of Captain (1869) an unsatisfactory private design by Lairds and Captain Coles. The rival Admiralty design, Monarch (1868), had a long and successful career. However the need to combine high-free-board at the bow with sails meant that both these ships had very poor end-on fire. The Admiralty's next seagoing mastless turret-ship design Devastation (1871) solved these problems by having very large coal bunkers, and put the 35-ton guns in turrets on a breastwork.[89]

Tank testing of hull models was introduced and mechanical calculators as range finders. The torpedo came in during the 1870s and the first ship to fire one in battle was HMS Shah.[90] This led to the development of torpedo boats and torpedo boat destroyers (later called just destroyers).[91]

| “ | Being unchallenged and unchallengable, Britain was able to exercise her maritime imperium of the Pax Britanica at remarkably modest expense. The British defence burden fell progressively to a minimum of 2 percent (of GDP) in 1870. Britain's dominance flowed not so much from the size of her active fleets as from the vast potential strength implicit in the reserve fleet and, behind that, the unrivalled capacity of her industry.[92] | ” |

At this time, 80% of merchant steamships were built in British shipyards.[92] The rate of French construction was low, and construction times were stretched out. For instance, the last of the three French 1872-programme battleships was not completed until October 1886.[93] Many of these long-delayed ships were completed in the second half of the 1880s, and this was misrepresented as the French having more new battleships than the Royal Navy in various publications including the famous 1884 articles in the Liberal magazine Pall Mall Gazette, which alarmed the public just before the General Election, and helped create an increased market for books on naval matters such as the Naval Annual, which was first published in 1887.[94]

Two-power standard

The age of naval dominance at low cost was ended by increased naval competition from old rivals, such as France, and new ones such as Imperial Germany and Japan. These challenges were reflected by the Naval Defence Act 1889, which received the Royal Assent on 31 May 1889, to increase the United Kingdom's naval strength and formally adopt the country's "two-power standard". The standard called for the Royal Navy to be as strong as the world's next two largest navies combined (at that point, France and Russia) by maintaining a number of battleships at least equal to their combined strength.[95]

That led to a new ship building programme, which authorised ten new battleships, 38 cruisers, and additional vessels. Alfred Thayer Mahan's books and his visit to Europe in the 1890s heightened interest even more.[96] When Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone held out against another large programme of naval construction in 1894, he found himself alone, and so resigned.[97]

Age of the battleship, 1895–1919

Both naval construction and naval strategizing became intense, prompted by the development of torpedoes and submarines (from 1901), which challenged traditional ideas about the power of battleships. At the same time the Dreadnought committed to the "big gun only" concept and caused a shift in thinking around the world, giving Britain the undisputed lead. This ship had ten 12-inch guns with a top speed of 21.5 knots. The British were aided in this development by having Naval Observers aboard the Japanese fleet at the battle of Tsushima straits in 1904 where the Japanese decisively defeated the Russian fleet.[98]

Another innovative (though ultimately unsuccessful) concept was the battlecruiser, fast and light but still hard-hitting. However, to achieve this the ship's armour was sacrificed. The result was a potentially fatal weakness.[99]

The Royal Navy began developing submarines beginning on 4 February 1901. These submarines were ordered in late 1900 and were built by Vickers under a licensing agreement with the American Electric Boat Company.[100] The first British Holland No. 1 (Type 7) submarine (assembled by Vickers) was 63 feet 4 inches long.[101]

Major reforms of the British fleet were undertaken, particularly by Admiral Jackie Fisher as First Sea Lord from 1904 to 1909. During this period, 154 obsolete ships, including 17 battleships, were scrapped to make way for newer vessels. Reforms in training and gunnery were introduced to make good perceived deficiencies, which in part Tirpitz had counted upon to provide his ships with a margin of superiority. Changes in British foreign policy, such as The Great Rapprochement with the United States, the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, and the Entente Cordiale with France allowed the fleet to be concentrated in home waters. By 1906 the Royal Navy's only likely opponent was the Imperial German Navy.[102]

Also, around this time, an important new development was under way. It was the steam turbine, invented by Charles Parsons, demonstrated by the Turbinia in 1899.[103]

In 1910, the NID was shorn of its responsibility for war planning and strategy when the outgoing Fisher created the Navy War Council as a stop-gap remedy to criticisms emanating from the Beresford Inquiry that the Navy needed a naval staff—a role the NID had been in fact fulfilling since at least 1900, if not earlier. After this reorganisation, war planning and strategic matters were transferred to the newly created Naval Mobilisation Department and the NID reverted to the position it held prior to 1887—an intelligence collection and collation organisation.[104]

Some countries from within the British Empire started developing their own navies. In 1911 the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Canadian Navy came into being. In 1941 the New Zealand Division became the Royal New Zealand Navy.[105]

All these reforms and innovations of course required a large increase in funding. Between 1900 and 1913 the Naval Estimates nearly doubled to total £44,000,000.[106] This was over half the total defence budget of £74,000,000 (£6.68 billion in 2018).[107]

World Wars, 1914–1945

First World War

The accumulated tensions in international relations finally broke out into the hostilities of World War I. From the naval point of view, it was time for the massed fleets to prove themselves, but caution and manoeuvring resulted in only a few minor engagements at sea. During the First World War the majority of the Royal Navy's strength was deployed at home in the Grand Fleet in an effort to blockade Germany and to draw the Hochseeflotte (the German "High Seas Fleet") into an engagement where a decisive victory could be gained. Although there was no decisive battle, the Royal Navy and the Kaiserliche Marine fought many engagements: the Battle of Heligoland Bight, the Battle of Coronel, the Battle of the Falkland Islands, the Battle of Dogger Bank and the Battle of Jutland. The British numerical advantage proved insurmountable, leading the High Seas Fleet to abandon any attempt to challenge British dominance.[108]

At the start of the war the German Empire had armed cruisers scattered across the globe. Some of them were used to attack Allied merchant shipping. The Royal Navy systematically hunted them down, though not without some embarrassment from its inability to protect friendly shipping. Most of the German East Asia Squadron was defeated at the Battle of the Falkland Islands in December 1914.[109]

Soon after the outbreak of hostilities the British initiated a Naval Blockade of Germany, preventing supplies from reaching its ports. International waters were mined to prevent any ships from entering entire sections of sea. Since there was limited response to this tactic, Germany expected a similar response to its tactic of unrestricted submarine warfare. This attempted to cut supply lines to Britain.[110]

The Royal Naval Air Service was formed in 1914 but was mainly limited to reconnaissance. Converted ships were initially used to launch aircraft with landings in the sea. The first purpose-built aircraft carrier was HMS Argus, launched in 1918.[111]

The Royal Navy was also heavily committed in the Dardanelles Campaign against the Ottoman Empire.[112] During the war, the Navy contributed the Royal Naval Division to the land forces of the New Army. The Royal Marines took part in many operations including the raid on Zeebrugge.[113]

Energy was a critical factor for the British war effort. Most of the energy supplies came from coal mines in Britain. Critical however was the flow of oil for ships, lorries and industrial use. There were no oil wells in Britain so everything was imported. In 1917, total British consumption was 827 million barrels, of which 85% was supplied by the United States, and 6% by Mexico.[114] Fuel oil for the Royal Navy was the highest priority. In 1917, the Royal Navy consumed 12,500 tons a month, but had a supply of 30,000 tons a month from the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, using their oil wells in Persia.[115]

Inter-war period

In the inter-war period the Royal Navy was stripped of much of its power. The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 imposed limits on individual ship tonnage and gun calibre, as well as total tonnage of the navy. The treaty, together with the deplorable financial conditions during the immediate post-war period and the Great Depression, forced the Admiralty to scrap all capital ships from the Great War with a gun calibre under 13.5 inches and to cancel plans for new construction.[116] The G3-class of 16-inch battlecruisers and the N3-class battleship of 18-inch battleships were cancelled. Three of the Admiral-class battlecruisers had already been cancelled. Also under the treaty, three "large light cruisers"—Glorious, Courageous and Furious—were converted to aircraft carriers. New additions to the fleet were therefore minimal during the 1920s, the only major new vessels being two Nelson-class battleships and fifteen County-class cruisers and York-class heavy cruisers.[117]

The London Naval Treaty of 1930 deferred new capital ship construction until 1937 and reiterated construction limits on cruisers, destroyers and submarines. As international tensions increased in the mid-1930s the Second London Naval Treaty of 1935 failed to halt the development of a naval arms race and by 1938 treaty limits were effectively ignored. The Navy made a show of force against Mussolini's war in Abyssinia, and operated in China to evacuate British citizens from cities under Japanese attack. The re-armament of the Royal Navy was well under way by this point however, with the King George V-class battleship of 1936, limited to 35,000 tons and 14-inch armament, the aircraft carrier Ark Royal, and the Illustrious-class aircraft carrier, the Town-class and Crown Colony-class classes of light cruiser and the Tribal-class destroyers.[118]

During this period the Royal Navy was used for evacuation and gunboat diplomacy. There were significant pay cuts in the 1920s, culminating in the Invergordon Mutiny of 1931. The crews of various warships refused to sail on exercises, which caused great shock. This led to changes and the pay rates were restored in 1934.[119]

Second World War

At the start of World War II, Britain's global commitments were reflected in the Navy's deployment. Its first task remained the protection of trade, since Britain was heavily dependent upon imports of food and raw materials, and the global empire was also interdependent. The navy's assets were allocated between various Fleets and Stations[120]

| Fleet / Station | Area of Responsibility |

|---|---|

| Home Fleet | Home waters, i.e., north-east Atlantic, North Sea, English Channel (sub-divided into commands and sub-commands) |

| Mediterranean Fleet | Mediterranean |

| South Atlantic Station | South Atlantic region |

| America and West Indies Station | Western north Atlantic, Caribbean, eastern Pacific |

| East Indies Station / Eastern Fleet | Indian Ocean (excluding South Atlantic and Africa Station, Australian waters and waters adjacent to Dutch East Indies) |

| China Station / Eastern Fleet | North-west Pacific and waters around Dutch East Indies |

At the start of the war in 1939, the Royal Navy was the largest in the world, with over 1,400 vessels.[121][122] The Royal Navy suffered heavy losses in the first two years of the war, including the carriers HMS Courageous, Glorious and Ark Royal, the battleships Royal Oak and Barham and the battlecruiser Hood in the European Theatre, and the carrier Hermes, the battleship Prince of Wales, the battlecruiser Repulse and the heavy cruisers Exeter, Dorsetshire and Cornwall in the Asian Theatre. Of the 1,418 men on the Hood, only three survived its sinking.[123] Over 3,000 people were lost when the converted troopship RMS Lancastria was sunk in June 1940, the greatest maritime disaster in Britain's history.[124] There were however also successes against enemy surface ships, as in the battles of the River Plate in 1939, Narvik in 1940 and Cape Matapan in 1941, and the sinking of the German capital ships Bismarck in 1941 and Scharnhorst in 1943.[125]

The Royal Navy was vital in interdicting Axis supplies to North Africa and in the resupply of its base in Malta. The losses in Operation Pedestal were high but the convoy got through.[126] The Royal Navy was also vital in guarding the sea lanes that enabled British forces to fight in remote parts of the world such as North Africa, the Mediterranean and the Far East. Convoys were used from the start of the war and anti-submarine hunting patrols used. From 1942, responsibility for the protection of Atlantic convoys was divided between the various allied navies: the Royal Navy being responsible for much of the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans.[127]

The defence of the ports and harbours and keeping sea-lanes around the coast open was the responsibility of Coastal Forces and the Royal Naval Patrol Service.[128] Naval supremacy was vital to the amphibious operations carried out, such as the invasions of Northwest Africa, Sicily, Italy, and Normandy. The use of the Mulberry harbours allowed the invasion forces to be kept resupplied.[129]

The successful invasion of Europe reduced the European role of the navy to escorting convoys and providing fire support for troops near the coast as at Walcheren, during the battle of the Scheldt.[130]

The British Eastern Fleet had been withdrawn to East Africa because of Japanese incursions into the Indian Ocean. Despite opposition from the U.S. naval chief, Admiral Ernest King, the Royal Navy sent a large task force to the Pacific (British Pacific Fleet). This required the use of wholly different techniques, requiring a substantial fleet support train, resupply at sea and an emphasis on naval air power and defence. Their largest attack was on the oil refineries in Sumatra to deny Japanese access to supplies.[131]

The Navy from 1945

Post-War period, 1945–1956

.jpg)

After the Second World War, the decline of the British Empire and the economic hardships in Britain forced the reduction in the size and capability of the Royal Navy. All of the pre-war ships (except for the Town-class light cruisers) were quickly retired and most sold for scrapping over the years 1945–48, and only the best condition ships (the four surviving KG-V class battleships, carriers, cruisers, and some destroyers) were retained and refitted for service. The increasingly powerful United States Navy took on the former role of the Royal Navy as global naval power and police force of the sea. The combination of the threat of the Soviet Union, and Britain's commitments throughout the world, created a new role for the Navy. Governments since the Second World War have had to balance commitments with increasing budgetary pressures, partly due to the increasing cost of weapons systems, what historian Paul Kennedy called the Upward Spiral.[132]

Cold War, 1956–1990

_Norfolk.jpg)

A modest new construction programme was initiated with some new carriers (Majestic- and Centaur-class light carriers, and Audacious-class large carriers being completed between 1948 through 1958), along with three Tiger-class cruisers (completed 1959–61), the Daring-class destroyers in the 1950s, and finally the County-class guided missile destroyers completed in the 1960s.[133]

Lord Mountbatten of Burma continued with development, and by 1962 a new Dreadnought became Britain's first nuclear-powered submarine and in 1968 the first ballistic missile submarine Resolution was commissioned, armed with the Polaris missile. The Royal Navy later became wholly responsible for the maintenance of the UK's nuclear deterrent. Even so, the Labour government announced in 1966 that Britain would not mount major operations without the help of allies, and that the existing carrier force would be maintained into the 1970s; Christopher Mayhew and Sir David Luce resigned in protest, but to no avail. Britain withdrew from the east of Suez, cancelling its planned CVA-01 large carrier, and other than Polaris focused on its NATO responsibilities of anti-submarine warfare, defending US Navy carrier groups in the GIUK gap.[134]

In the North Atlantic, the United Kingdom became engaged in a protracted dispute with Iceland over fishing rights. The Royal Navy, supported by tugs from the MAFF and British civilian trawlers, was involved in three major confrontations with the Icelandic Coast Guard from 1958 to 1976. These largely bloodless incidents became known as the Cod Wars, and ended with the recognition by Britain of Iceland's exclusive 200 nautical miles fishery zone.[135]

Chatham Naval Base was used for refitting nuclear submarines from 1963 but it closed in 1984.[136]

Falklands War, 1982

.jpg)

The most important operation conducted predominantly by the Royal Navy after the Second World War was the defeat in 1982 of Argentina in the Falkland Islands War. Only four days after the invasion on 2 April, a Task Force sailed for the South Atlantic, with other warships and support ships following. On 25 April the navy retook South Georgia, crippling an Argentine submarine called the Santa Fė.[137] Despite losing four naval ships and other civilian and RFA ships the Royal Navy proved it was still able to fight a battle 8,345 miles (12,800 km) from Great Britain. HMS Conqueror is the only nuclear-powered submarine to have engaged an enemy ship with torpedoes, sinking the Argentine cruiser ARA General Belgrano.[138]

Operations after 1982

In the latter stages of the Cold War, the Royal Navy was reconfigured with three anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft carriers and a force of frigates and destroyers. Its purpose was to search for and destroy Soviet submarines in the North Atlantic. There were also mine countermeasures and submarine forces as well as support ships. As the Cold War ended, the Royal Navy fought in the Gulf War against Iraq, with Sea Skua anti-ship missiles sinking a large proportion of the Iraqi Navy.[139] The WRNS was amalgamated with the RN in 1993.[140]

The Strategic Defence Review of 1998 and the follow-on Delivering Security in a Changing World White Paper of 2004 promised a somewhat brighter long-term future for the Navy, putting in place the largest naval procurement programme since the end of the Second World War in order to enhance and rebuild the fleet, with a view to bringing the Navy's capabilities into the 21st century, and restructuring the fleet from a North Atlantic-based, large Anti-Submarine force into a true blue water navy once more. Whilst several smaller vessels were to be withdrawn from service, it was confirmed that two new large aircraft carriers would be constructed.[141]

| Vessel class | SDR Requirement | 2007 levels [142] |

|---|---|---|

| Carriers | 3 Invincible class or 2 CVF | 3 Invincible class |

| Amphibious warfare | 8 | 5 (inc RFA vessels) |

| Attack submarines | 10 | 9 |

| Destroyers and frigates | 32 | 25 |

| Mine warfare | 22 | 16 |

The Navy took part in the 2003 Iraq War which saw RN warships bombard positions in support of the Al Faw Peninsula landings by Royal Marines.[143] Also during that war, HMS Splendid and Turbulent (S87) launched a number of Tomahawk cruise missiles at targets in Iraq.[144]

In 2004, Iranian armed forces took Royal Navy personnel prisoner, including Royal Marines, on the Shatt al-Arab (Arvand Rud in Persian) river, between Iran and Iraq. They were released three days later following diplomatic discussions between the UK and Iran.[145] In August 2005 the Royal Navy rescued seven Russians stranded in a submarine off the Kamchatka peninsula. Using its Scorpio 45, a remote-controlled mini-sub, the submarine was freed from the fishing nets and cables that had held the Russian submarine for three days.[146]

In 2007, Iranian armed forces also took prisoner Royal Navy personnel, including Royal Marines, when a boarding party from HMS Cornwall was seized in the waters between Iran and Iraq, in the Persian Gulf. They were released thirteen days later.[147] The Royal Navy was also involved in an incident involving Somali pirates in November 2008, after the pirates tried to capture a civilian vessel.[148]

Trends in ship strength

In numeric terms the Royal Navy has significantly reduced in size since the 1960s, reflecting the reducing requirement of the state. This raw figure does not take into account the increase in technological capability of the Navy's ships, but it does show the general reduction of capacity.[149] The following table is a breakdown of the fleet numbers since 1960. The separate types of ship and how their numbers have changed are shown.[150]

| Year[150] | Submarines | Carriers | Assault ships | Surface combatants | Mine countermeasure vessels | Patrol ships and craft | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | SSBN | SSN | SS & SSK | Total | CV | CV(L) | Total | Cruisers | Destroyers | Frigates | |||||

| 1960 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 145 | 6 | 55 | 84 | ? | ? | 202 |

| 1965 | 47 | 0 | 1 | 46 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 117 | 5 | 36 | 76 | ? | ? | 170 |

| 1970 | 42 | 4 | 3 | 35 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 97 | 4 | 19 | 74 | ? | ? | 146 |

| 1975 | 32 | 4 | 8 | 20 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 72 | 2 | 10 | 60 | 43 | 14 | 166 |

| 1980 | 32 | 4 | 11 | 17 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 67 | 1 | 13 | 53 | 36 | 22 | 162 |

| 1985 | 33 | 4 | 14 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 56 | 0 | 15 | 41 | 45 | 32 | 172 |

| 1990 | 31 | 4 | 17 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 49 | 0 | 14 | 35 | 41 | 34 | 160 |

| 1995 | 16 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 35 | 0 | 12 | 23 | 18 | 32 | 106 |

| 2000 | 16 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 32 | 0 | 11 | 21 | 21 | 23 | 98 |

| 2005 | 15 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 28 | 0 | 9 | 19 | 16 | 26 | 90 |

| 2010 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 24 | 0 | 7 | 17 | 16 | 23 | 78 |

| 2015 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 19 | 0 | 6 | 13 | 15 | 23 | 70 |

- One icebreaker patrol ship in service, counted under "patrol ships and craft".

- A third Astute class submarine HMS Artful has been launched, and will start sea trials in late 2015. The submarine will replace the recently decommissioned HMS Tireless of the Trafalgar class submarine.

- Current figures exclude the main 13 auxiliary support vessels currently used by the Royal Fleet Auxiliary that provide at sea replenishment, as sea maintenance if required, some patrol tasks acting as "mothership" and also form as a main logistics transport fleet, utilizing vessels such as the Bay-class landing ship and others.

English navy/Royal Navy timeline and battles

- 1213 Battle of Damme

- 1338 Battle of Arnemuiden

- 1340 Battle of Sluys

- 1350 Battle of Winchelsea

- 1372 Battle of La Rochelle

- 1512 Battle of Saint-Mathieu

- 1545 Battle of the Solent

- 1585–1604 Anglo–Spanish War (1585)

- 1625 Cádiz Expedition (1625)

- 1627–1629 Anglo-French War (1627–1629)

- 1652–1654 First Anglo–Dutch War

- 1654–1660 Anglo-Spanish War (1654)

- 1665–1667 Second Anglo-Dutch War

- 1672–1674 Third Anglo-Dutch War

- 1688–1697 Nine Years' War

- 1701–1713 War of the Spanish Succession

- 1718–1720 War of the Quadruple Alliance

- 1740–1748 War of the Austrian Succession

- 1754–1763 Seven Years' War

- 1778–1783 American War of Independence

- 1793–1802 French Revolutionary Wars

- 1803–1815 Napoleonic Wars

- 1812–1814 War of 1812

- 1821 First paddle steamer for auxiliary use

- 1827 Battle of Navarino is the last fleet action between wooden sailing ships.

- 1839–1842 Opium War

- 1840 First screw-driven warship, Rattler

- 1853–1856 Crimean War

- 1856–1860 Second Opium War

- 1860 First iron-hulled armoured battleship, Warrior

- 1902 First British submarine, HMS Holland 1

- 1905 First steam turbine-powered "all big-gun" battleship, Dreadnought

- 1914–1918 First World War

- 1918 First true aircraft carrier, HMS Argus

- 1918–1920 Russian Civil War

- 1931 Invergordon Mutiny

- 1939–1945 Battle of the Atlantic

- 1940 Norwegian Campaign

- 1940 Dunkirk evacuation

- 1940–1944 Battle of the Mediterranean

- 1941–1945 Arctic Convoys

- 1941–1945 South-East Asian Theatre

- 1944 Normandy Landings

- 1944–1945 British Pacific Fleet

- 1946 Corfu Channel Incident

- 1949 Amethyst incident on the Yangtze River

- 1950–1953 Korean War

- 1956 Suez Crisis

- 1958–1976 Cod Wars

- 1959 The last battleship, Vanguard, is decommissioned.

- 1962–1966 Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation

- 1963 First British nuclear submarine, Dreadnought

- 1966–1975 Beira Patrol against Rhodesia

- 1977 Operation Journeyman to guard the Falkland Islands

- 1980–2002 Armilla patrol in the Persian Gulf

- 1982 Falklands War

- 1991 First Gulf War

- 1999 Operation Allied Force – Kosovo conflict

- 2000 Operation Palliser – Sierra Leone

- 2001–2014 Operation Herrick – Afghanistan Campaign

- 2002–present Combined Maritime Forces in the Indian Ocean

- 2003–2009 Operation Telic – Invasion of Iraq

- 2011 Operation Ellamy – Libyan Civil War

- 2014–present Operation Shader – Military intervention against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

See also

Notes

- ↑ Swanton, p. 39

- ↑ Savage, p. 84