Kingdom of Northumbria

| Kingdom of Northumbria Norþanhymbra Rīce | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 653–954 | |||||||||||||||||

Extent of Northumbria in 800 | |||||||||||||||||

| Status |

Unified Angle kingdom (before 876) North: Angle kingdom (after 876) South: Danish kingdom (876–914) South: Norwegian kingdom (after 914) | ||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

Northern: Bamburgh Southern: York | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old English, Cumbric, Latin | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||

• 654–670 | Oswiu | ||||||||||||||||

• died 954 | Eric Bloodaxe | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Established | 653 | ||||||||||||||||

• South is annexed by the Danelaw | 876 | ||||||||||||||||

• South is conquered by Norse warriors | 914 | ||||||||||||||||

• Annexed by Wessex | 954 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Sceat (peninga) | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of |

∟ North East of England ∟ North West of England (except Cheshire) ∟ Yorkshire and the Humber ∟ Lincolnshire (part, corresponding to modern day East Lindsey, Lincoln and West Lindsey) ∟ City of Edinburgh ∟ East Lothian ∟ Midlothian ∟ West Lothian ∟ Scottish Borders | ||||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Northumbria (/nɔːrˈθʌmbriə/; Old English: Norþanhymbra Rīce[1]) was a medieval Anglian kingdom in what is now northern England and south-east Scotland. The name derives from the Old English Norþan-hymbre meaning "the people or province north of the Humber",[2] which reflects the approximate southern limit to the kingdom's territory, the Humber Estuary. Northumbria started to consolidate into one kingdom in the early seventh century. At its height, the kingdom extended from just south of the Humber to the River Mersey and to the Firth of Forth, in Scotland. Northumbria ceased to be an independent kingdom in the mid-tenth century.

Northumbria is also used in the names of some North East regional institutions, particularly the police force (Northumbria Police, which covers Northumberland and Tyne and Wear), a university (Northumbria University) based in Newcastle upon Tyne and Northumbria Army Cadet Force, as well as the regionalist Northumbrian Association[3]. The local Environment Agency office, located in Newcastle Business Park, also uses the term Northumbria to describe its area. Otherwise, the term is not the official name for the UK and EU region of North East England.

Kingdom (654–954)

Communities and Divisions

Possible British Origins

The Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria was originally two kingdoms divided approximately around the River Tees: Bernicia was to the north of the river and Deira to the south[4]. It is possible that both regions originated as native British Kingdoms which the Germanic settlers later conquered, although there is very little information about the infrastructure and culture of the British kingdoms themselves[5]. Much of the evidence for them comes from regional names that are British rather than Anglo-Saxon in origin. The names Deira and Bernicia likely originate from British words, for example, indicating that some British place names retained currency after the Anglo-Saxon migrations to Northumbria[lower-alpha 1]. There is also some archeological evidence to support British origins for the polities of Bernicia and Deira. In what would have been southern Bernicia, in the Cheviot Hills, a hill fort at Yeavering called Yeavering Bell contains evidence that it was an important centre for first the British and later the Anglo-Saxons. The fort is originally pre-Roman, dating back to the Iron Age at around the first century. In addition to signs of Roman occupation, the site contains evidence of timber buildings that pre-date Germanic settlement in the area that are probably signs of British settlement. Moreover, Brian Hope-Taylor has traced the origins of the name Yeavering, which looks deceptively English, back to the British gafr from Bede’s mention of a township called Gefrin in the same area.[9][10] Yeavering continued to be an important political centre after the Anglo-Saxons began settling in the north, as King Edwin had a royal palace at Yeavering.[11]

Overall, English place-names dominate the Northumbrian landscape, suggesting the prevalence of an Anglo-Saxon elite culture by the time that Bede—one of Anglo-Saxon England’s most prominent historians—was writing in the eighth century.[12][13] According to Bede, the Angles predominated the Germanic immigrants that settled north of the Humber and gained political prominence during this time period.[14] While the British natives may have partially assimilated into the Northumbrian political structure, relatively contemporary textual sources such as Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People depict relations between Northumbrians and the British as fraught.[15]

The Unification of Bernicia and Deira

The Anglo-Saxon countries of Bernicia and Deira were often in conflict before their eventual semi-permanent unification in 654. Political power in Deira was concentrated in the East Riding of Yorkshire, which included York, the North York Moors, and the Vale of York.[16] The political heartlands of Bernicia were the areas around Bamburgh and Lindisfarne, Monkwearmouth and Jarrow, and in Cumbria, west of the Pennines in the area around Carlisle.[17] The name that these two countries eventually united under, Northumbria, may have been coined by Bede and made popular through his Ecclesiastical History of the English People.[18]

Information on the early royal genealogies for Bernicia and Deira comes from Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People and Welsh chronicler Nennius’ Historia Brittonum. According to Nennius, the Bernician royal line begins with Ida, son of Eoppa.[19] Ida reigned for twelve years (beginning in 547) and was able to annex Bamburgh to Bernicia.[20] In Nennius’ genealogy of Deira, a king named Soemil was the first to separate Bernicia and Deira, which could mean that he wrested the kingdom of Deira from the native British.[21] The date of this supposed separation is unknown. The first Deiran king to make an appearance in Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum is Ælle, the father of the first Roman Catholic Northumbrian king Edwin.[22]

A king of Bernicia, Ida’s grandson Æthelfrith, was the first ruler to unite the two polities under his rule. He exiled the Deiran Edwin to the court of King Rædwald of the East Angles in order to claim both kingdoms, but Edwin returned in approximately 616 to conquer Northumbria with Rædwald’s aid.[23][24] Edwin, who ruled from approximately 616 to 633, was one of the last kings of the Deiran line to reign over all of Northumbria; it was Oswald of Bernicia (c. 634-42) who finally succeeded in making the merger more permanent.[25] Oswald’s brother Oswiu eventually succeeded him to the Northumbrian throne despite initial attempts on Deira’s part to pull away again.[24] Although the Bernician line ultimately became the royal line of Northumbria, a series of Derian sub-kings continued after Oswald, including Oswine (a relation of Edwin murdered by Oswiu in 651), Œthelwald (killed in battle 655), and Aldfrith (son of Oswiu, who disappeared after 664).[24] Although both Œthelwald and Aldfrith were Oswiu’s relations who may have received their sub-king status from him, both used Deira separatist sentiments to try to snatch independent rule of Deira.[21] Ultimately, neither were successful and Oswiu’s son Ecgfrith succeeded him to maintain the integrated Northumbrian line.[24]

While violent conflicts between Bernicia and Deira played a significant part in determining which line ultimately gained supremacy in Northumbria, marriage alliances also helped bind these two territories together. Æthelfrith married Edwin’s sister Acha, although this marriage did little to prevent future squabbles between the brothers-in-law and their descendants. The second intermarriage was more successful, with Oswiu marrying Edwin’s daughter and his own cousin Eanflæd to produce Ecgfrith, the beginning of the Northumbrian line. However, Oswiu had another relationship with an Irish woman named Fina which produced the problematic Aldfrith.[24] In his Life and Miracles of St. Cuthbert, Bede declares that Aldfrith, known as Fland among the Irish, was illegitimate and therefore unfit to rule.[26]

Northumbria and Norse Settlement

The Viking invasions of the ninth century and the establishment of the Danelaw once again divided Northumbria. Although primarily recorded in the southern provinces of England, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (particularly the D and E recensions) provide some information on Northumbria’s conflicts with Vikings in the late eighth and early ninth centuries. According to these chronicles, Viking raids began to affect Northumbria when a band attacked Lindisfarne in 793.[27] After this initial catastrophic blow, Viking raids in Northumbria were either sporadic for much of the early ninth century or evidence of them was lost.[28] However, in 865 the so-called Great Heathen Army landed in East Anglia and began a sustained campaign of conquest.[29][30] The Great Army fought in Northumbria in 866–867, striking York twice in less than one year. After the initial attack the Norse left to go north, leaving Kings Ælle and Osberht to recapture the city. The E recension of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle suggests that Northumbria was particularly vulnerable at this time because the Northumbrians were once again fighting among themselves, deposing Osberht in favor of Ælle.[31] In the second raid the Vikings killed the Northumbrian kings Ælle and Osberht while recapturing the city.[29]

After King Alfred reestablished his control of southern England the Norse invaders settled into what came to be known as the Danelaw in the Midlands, East Anglia, and the southern part of Northumbria.[29] In Northumbria, the Norse established the Kingdom of York whose boundaries were roughly the River Tees and the Humber, giving it approximately the same dimensions as Deira.[32] Although this kingdom fell to Hiberno-Norse colonizers in the 920s and was in constant conflict with the West-Saxon expansionists from the south, it survived until 954 when the last Scandinavian king Eric, who is usually identified as Eric Bloodaxe, was driven out and eventually killed.[33][34][35]

In contrast, the Great Army was not as successful in conquering territory north of the River Tees. There were raids that extended into that area, but no sources mention lasting Norse occupation and there are very few Scandinavian place names to indicate significant Norse settlement in northern regions of Northumbria.[36] The political landscape of the area north of the Tees during the Viking conquest of Northumbria consisted of the Community of St. Cuthbert and the remnants of the English Northumbrian elites.[37] While the religious Community of St. Cuthbert "wandered" for a hundred years after Halfdan Ragnarsson attacked their original home Lindisfarne in 875, The History of St. Cuthbert indicates that they settled temporarily at Chester-le-Street between the years 875–883 on land granted to them by the Viking King of York, Guthred.[38][39] According to the twelfth-century account Historia Regum, Guthred granted them this land in exchange for their raising him up as king. The land extended from the Tees to the Tyne and anyone who fled there from either the north or the south would receive sanctuary for thirty-seven days, indicating that the Community of St. Cuthbert had some juridical autonomy. Based on their positioning and this right of sanctuary, this community may have acted as a buffer between the Norse in southern Northumbria and the Anglo-Saxons who continued to hold the north.[40][41]

North of the Tyne, Northumbrians maintained partial political control in Bamburgh. The rule of kings continued in that area with Ecgberht I acting as regent around 867 and the kings Ricsige and Ecgberht II immediately following him.[42] According to twelfth-century historian Symeon of Durham, Ecgberht I was a client-king for the Norse. The Northumbrians revolted against him in 872, deposing him in favor of Ricsige.[43] Although the A and E recensions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle report that Halfdan was able to take control of Deira and take a raiding party north of the River Tyne to impose his rule on Bernicia in 874, after Halfdan’s death (c. 877) the Norse had difficulty holding on to territory in northern Bernicia.[44][45] Ricsige and his successor Ecgberht were able to maintain an English presence in Northumbria. After the reign of Ecgberht II, Eadwulf "King of the North Saxons" (r. 890–912) succeeded him for control of Bamburgh, but after Eadwulf rulership of this area switched over to earls who may have also been related to the last of the royal Northumbrian house.[46]

Notable Kings

Æthelfrith (r. 593–616)

Æthelfrith was the first Anglo-Saxon leader to hold the thrones of both Deira and Bernicia,[47] and so he ruled over all the people north of the Humber. His rule was notable for his numerous victories over the Britons and the Gaels.[48]

Edwin (r. 616–633)

Edwin, like Æthelfrith, was king of both Deira and Bernicia and ruled them from 616 to 633. Under his reign the Isle of Man and the lands of Gwynedd in Northern Wales were incorporated into Northumbria. Edwin married Æthelburh, a Catholic Princess from Kent in 625. He converted to Roman Cathoicism two years later after a period of heavy consideration and after consulting numerous advisors.[49] Edwin fell in battle in 633 against the pagan kings Cadwallon of Gwynedd and Penda of Mercia.[50] He was venerated as a Catholic saint and martyr after his death.[51]

Oswald (r. 634–642)

Oswald was a King of Bernicia, who would regain the kingdom of Deira after defeating Cadwallon in 634. Oswald would then rule Northumbria until his death in 642. A devout Catholic, Oswald worked tirelessly to spread the religion in his traditionally pagan lands. It was during his reign that the monastery at Lindisfarne was created. Oswald fell in the Battle of Maserfield against Penda of Mercia in 642 but his influence endured because, like Edwin, Oswald was venerated as a saint after his death.[52]

Oswiu (r. 642–670)

Oswiu was the brother of Oswald and succeeded him after the latter’s defeat in Maserfield. Oswiu succeeded where Edwin and Oswald failed as, in 655, he slew Penda during the Battle of the Winwaed, making him the first Northumbrian King to also control the kingdom of Mercia.[53] During his reign, he presided over the Synod of Whitby, an attempt to reconcile religious differences between Roman and Celtic Catholicism, in which he eventually backed the Roman beliefs.[54] Oswiu died from illness in 670 and divided Deira and Bernicia between two of his sons.[55]

Halfdan Ragnarsson (r. 876–877)

Halfdan Ragnarsson was a Viking leader of the Great Heathen Army which invaded England in 865.[56] He allegedly wanted revenge against Northumbria for the death of his father, who was supposedly killed by Ælla of Northumbria.[57] While he himself only ruled Northumbria directly for about a year in 876, he placed Ecgberht on the throne as a client-king, who ruled from 867 to 872.[58] Halfdan was killed in Ireland in 877 whilst trying to regain control over Dublin, a land he had ruled since 875. There were no further Viking kings in Northumbria until Guthfrith took over in 883.[59]

Æthelstan of Wessex (r. 927–939)

Æthelstan ruled as King of the Anglo-Saxons from 924 to 927 and King of the English from 927 to 939. The shift in his title reflects that in 927, Æthelstan conquered the Viking Kingdom of York, previously part of the Northumbrian Kingdom.[60] His reign was quite prosperous and saw great strides in many fields such as law and economics, but was also characterized by frequent clashes with the Scots and the Vikings.[61] Æthelstan died in 939, which led to the Vikings’ retaking of York. Æthelstan is widely considered one of the greatest Anglo-Saxon kings for his efforts to consolidate the English kingdom and the prosperity his reign brought.[62]

Eric of York (r. 947–948, 952–954)

In the early twentieth century, historians identified Eric of York with the Norwegian king Eric Bloodaxe, but some more recent scholarship has challenged this association. He held two short terms as King of Northumbria, from 947 to 948 and 952 to 954.[lower-alpha 2] Historical documentation on his reign is scarce, but it seems Eric pushed out the joint English-Viking rulers of Northumbria in 947 [63] who were then able to regain the land in 948/9. Eric took back the throne in 952, only to be deposed again in 954.[64] Eric of York was the last Danish King of Northumbria, as after his death in 954 Eadred of Wessex stripped the kingdom’s independent status and made the land part of England.

Eadred of Wessex (r. 946–954)

Eadred of Wessex was the half-brother of Æthelstan and Eadmund of Wessex, all of whom were fathered by Edward the Elder. He was nominally the ruler of Northumbria from 946, as he succeeded Eadmund, but had to deal with the threat of independent Viking kingdoms under Amlaíb Cuarán and Eric Bloodaxe. He permanently absorbed Northumbria into the English Kingdom in 954 after the death of Eric. [65]

Politics and War

Between the years of 737 AD and 806 AD Northumbria had 10 kings.[66] These kings were either murdered, deposed, exiled, or they became monks. However, kings throughout the entirety of Northumbria’s history were susceptible to these methods of overthrowing regents. Between Oswiu, the first King of Northumbria in 654, and Eric Bloodaxe, the last king of Northumbria in 954, there were 45 Kings, meaning that the average length of reign during the entire history of Northumbria is only six and a half years. Of the 25 Kings before the Danish rule of Northumbria, only four died of natural causes. Of those that did not abdicate for a holy life, the rest were either deposed, exiled, or murdered. Kings during the Danish rule of Northumbria (see Danelaw) were often either kings of a larger North Sea or Danish empire, or were installed rulers.[67]

Succession in Northumbria was hereditary [68], which left princes whose fathers died before they could come of age particularly susceptible to assassination and usurpation. A noteworthy example of this phenomenon is Osred, whose father Aldfrith died in 705, leaving the young boy to rule. He survived one assassination attempt early in his rule, but fell victim to another assassin at the age of nineteen. During his reign he was adopted by Wilfrid, a powerful bishop.[69] Ecclesiastical influence in the royal court was not an unusual phenomenon in Northumbria, and usually was most visible during the rule of a young or inexperienced king. Similarly, ealdorman, or royal advisors, had periods of increased or decreased power in Northumbria, depending on who was ruling at the time.[70]

Warfare in Northumbria before the Danish period largely consisted of rivalries with the Picts to the north. The Northumbrians were successful against the Picts until the Battle of Dun Nechtain in 685, which halted their expansion north and established a border between the two kingdoms. Warfare during the Danish period was dominated by warfare between the Northumbrians and other English Kingdoms.

Ealdormen and Earldoms of Northumbria

After the English absorbed the territory of the former kingdom, Scots invasions reduced Northumbria to an earldom stretching from the Humber to the Tweed. Northumbria was disputed between the emerging kingdoms of England and Scotland.

Religion

Roman and Post-Roman Britain

Under Roman rule, some Britons north of the Humber practiced Roman Catholicism. In fact, York had a bishop as early as the fourth century.[71] After the Romans left Britain in the early fifth century, Catholicism did not disappear, [72] but it existed alongside Celtic paganism,[73] and possibly many other cults.[74] Anglo-Saxons brought their own Germanic pagan beliefs and practices when they settled there. At Yeavering, in Bernicia, excavations have uncovered evidence of a pagan shrine, animal sacrifice, and ritual burials.[75]

Conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Roman Catholicism

The first King of Northumbria to convert to Roman Catholicism was King Edwin. He was baptized by Paulinus in 627.[76] Shortly thereafter, many of his people followed his conversion to the new religion, only to return to paganism when Edwin was killed in 633. Paulinus was Bishop of York, but only for a year.[77]

The lasting conversion of Northumbria took place under the guidance of the Irish cleric Aidan. He converted King Oswald of Northumbria in 635, and then worked to convert the people of Northumbria.[78] King Oswald moved the bishopric from York to Lindisfarne.[79]

Monasteries and Figures of Note

The monastery at Lindisfarne was founded by Aidan in 635, and based on the practices of the Columban monastery in Iona, Scotland.[80] The location of the bishopric shifted to Lindisfarne, and it became the centre for religion in Northumbria. The bishopric would not leave Lindisfarne and shift back to its original location at York until 664.[81] Throughout the eighth century, Lindisfarne was associated with important figures. Aidan, the founder, Wilfrid, a student, and Cuthbert, a member of the order and a hermit, all became bishops and later Saints. Aidan assisted Heiu to found her double monastery at Hartlepool.[82] She too came to be venerated as a saint.[83]

The Catholic culture of Northumbria was influenced by the continent as well as Ireland. In particular, Wilfrid travelled to Rome and abandoned the traditions of the Celtic church in favor of Roman practices. When he returned to England, he became abbot of a new monastery at Ripon in 660. Wilfrid advocated for Roman Catholicism at the Synod of Whitby. The two halves of the double monastery Monkwearmouth-Jarrow were founded by the nobleman Benedict Biscop in 673 and 681. Biscop became the first abbot of the monastery, and travelled to Rome six times to buy books for the library.[84] His successor, Abbot Ceolfrith, continued to add to the library until it. One estimate puts the library at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow at over two hundred volumes.[84] One who benefited from this library was Bede.[85]

In the early seventh century in York, Paulinus founded a school and a minster, but not a monastery. The School at York Minster is one of the oldest in England.[86] By the late eighth century, the school had a noteworthy library, estimated at about one hundred volumes.[87] Alcuin was a student and teacher at York before he left for the court of Charlemagne in 782.[88]

Synod of Whitby

In 664, King Oswiu called the Synod of Whitby to determine whether to follow Roman or Irish customs. Since Northumbria was converted to Roman Catholicism by the Celtic clergy, the Celtic tradition for determining the date of Easter and Irish tonsure were supported by many, particularly by the Abbey of Lindisfarne. Roman Catholicism was also represented in Northumbria, by Wilfrid, Abbot of Ripon. By the year 620, both sides were associating the other’s Easter observance with the Pelagian Heresy.[89] The King decided at Whitby that Roman practice would be adopted throughout Northumbria, thereby bringing Northumbria in line with Southern England and Western Europe.[90] Members of the clergy who refused to conform, including the Celtic Bishop Colman of Lindisfarne, returned to Iona.[91] The episcopal seat of Northumbria transferred from Lindisfarne to York, which later became an archbishopric in 735.[92]

Effects of Scandinavian Attack, Settlement and Culture on Religion

The Viking attack on Lindisfarne in 793 was the first of many raids on monasteries of Northumbria. The Lindisfarne Gospels survived, but monastic culture in Northumbria went into a period of decline in the early ninth century. Repeated Viking assaults on religious centres were one reason for the decrease in production of manuscripts and communal monastic culture. [93]

After 867, Northumbria came under control of the Scandinavian forces, and there was an influx of Scandinavian immigrants.[94] Their religion was pagan and had a rich mythology. Within the Kingdom of York, once the raids and war were over, there is no evidence that the presence of Scandinavian settlers interrupted Catholic practice. It appears that they gradually adopted Roman Catholicism and blended their Scandinavian culture with their new religion. This can be seen in carved stone monuments and ring-headed crosses, such as the Gosforth Cross.[95] During the ninth and tenth centuries, there was an increase in the number of parish churches, often including stone sculptures incorporating Scandinavian designs.[96]

Culture

The Golden Age of Northumbria

The Catholic culture of Northumbria, fuelled by influences from the continent and Ireland, promoted a broad range of literary and artistic works.

Insular Art

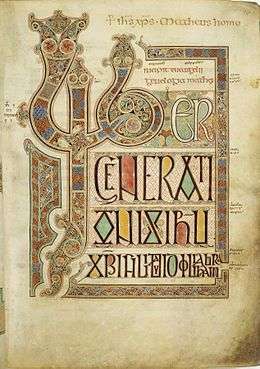

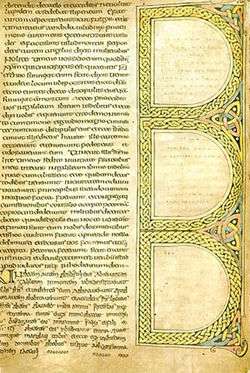

The Irish monks who converted Northumbria to Roman Catholicism, and established monasteries such as Lindisfarne, brought a style of artistic and literary production.[97] Eadfrith of Lindisfarne produced the Lindisfarne Gospels in an Insular style.[98]

The Irish monks brought with them an ancient Celtic decorative tradition of curvilinear forms of spirals, scrolls, and doubles curves. This style was integrated with the abstract ornamentation of the native pagan Anglo-Saxon metalwork tradition, characterized by its bright coloring and zoomorphic interlace patterns.[99]

Insular art, rich in symbolism and meaning, is characterized by its concern for geometric design rather than naturalistic representation, love of flat areas of color, and use of complicated interlace patterns.[100] All of these elements appear in the Lindisfarne Gospels (early eighth century). The Insular style was eventually imported to the European continent, exercising great influence on the art of the Carolingian empire.[101]

Usage of the Insular style was not limited to manuscript production and metalwork. It can be seen in and sculpture, such as the Ruthwell Cross and Bewcastle Cross. The devastating Viking raid on Lindisfarne in 793 marked the beginning of a century of Viking invasions that severely limited the production and survival of Anglo-Saxon material culture.[102] It heralded the end of Northumbria's position as a centre of influence, although in the years immediately following visually rich works like the Easby Cross were still being produced.

Literature

The Venerable Bede (673–735) is the most famous author of the Anglo-Saxon Period, and a native of Northumbria. His Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People, completed in 731) has become both a template for later historians and a crucial historical account in its own right[103], and much of it focuses on Northumbria.[104][105] He's also famous for his theological works, and verse and prose accounts of holy lives[106].After the Synod of Whitby, the role of the European continent gained importance in Northumbrian culture. During the end of the eighth century, the scriptorium at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow was producing manuscripts of his works for high demand on the Continent.[107]

Northumbria was also home to several Anglo-Saxon Catholic poets. Cædmon lived at the double monastery of Streonæshalch (Whitby Abbey) during the abbacy (657–680) of St. Hilda (614–680). According to Bede, he "was wont to make religious verses, so that whatever was interpreted to him out of scripture, he soon after put the same into poetical expressions of much sweetness and humility in English, which was his native language. By his verse the minds of many were often excited to despise the world, and to aspire to heaven."[108] His sole surviving work is Cædmon's Hymn. Cynewulf, prolific author of The Fates of the Apostles, Juliana, Elene, and Christ II, is believed to have been either Northumbrian or Mercian[109][110].

Scandinavians and the Danelaw

From around 800, there had been waves of Danish raids on the coastlines of the British Isles[111]. These raids terrorized the populace, but exposure to Danish society brought new opportunities for wealth and trade[112]. In 865, instead of raiding, the Danes landed a large army in East Anglia, and had conquered a territory known as the Danelaw, including Northumbria, by 867.[111][113] At first, the Scandinavian minority, while politically powerful, remained culturally distinct from the English populace. For example, only a few Scandinavian words, mostly military and technical, became part of Old English. By the early 900s, however, Scandinavian-style names for both people and places became increasingly popular, as did Scandinavian ornamentation on works of art, featuring aspects of Norse mythology, and figures of animals and warriors. Nevertheless, sporadic references to "danes" in charters, chronicles, and laws indicate that during the lifetime of the Kingdom of Northumbria, most inhabitants of northeast England did not consider themselves Danish, and were not perceived as such by other Anglo-Saxons.[114]

The synthesis of Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian and Catholic and Pagan visual motifs within the Danelaw can be illustrated by an examination of stone sculpture. However, the tradition of mixing pagan and Catholic motifs is not unique to the Danelaw, and examples of such synthesis can be seen in previous examples, such as the Franks Casket. The Franks Casket, believed to have been produced in Northumbria, includes depictions of Germanic legends and stories of the founding Roman and the Roman Church and is dated to the early eighth century.[115] The Gosforth Cross, dated to the early tenth century, stands at 4.4 meters and is richly decorated with carvings of mythical beasts, Norse gods, and Catholic symbolism.[116] Stone sculpture was not a practice of native Scandinavian culture, and the proliferation of stone monuments within the Danelaw shows the influence that the English had on Viking settlers. On one side of the Gosforth Cross is a depiction of the Crucifixion; whilst on the other are scenes from Ragnarok. The melding of these distinctive religious cultures can further be seen in the depiction of Mary Magdalene as a valkyrie, with a trailing dress and long pigtail.[117] Although one can read the iconography as the triumph of Catholicism over paganism, it is possible that in the process of the Catholicizing (as distinct from conversion) the Vikings might have initially accepted the Catholic god as an addition to the broad pantheon of Pagan gods.[118] The inclusion of pagan traditions in visual culture reflects the creation of a distinctive Anglo-Scandinavian culture. Consequently, this indicates that conversion not only required a change in belief, but also necessitated its assimilation, integration, and modification into existing cultural structures.[119]

Economy

Northumbria's economy centred around agriculture, with livestock and land being popular units of value in local trade[120]. By the mid 800s, the Open field system was likely the pre-eminent mode of farming. Like much of eastern England, Northumbria exported grain, silver, hides, and slaves[121]. Imports from Frankia included oil, luxury goods, and clerical supplies in the 700s[122][123][124]. Especially after 793, raids, gifts, and trade with Scandinavians resulted in substantial economic ties across the North Sea.

When coinage (as opposed to bartering) regained popularity in the late 600s, Northumbrian coins featured kings' names, indicating royal control of currency. Royal currency was unique in Britain for a long time. King Aldfrith (685–705) minted Northumbria's earliest silver coins, likely in York. Later royal coinage bears the name of King Eadberht (738–758), as well as his brother, archbishop Ecgbert of York[125]. Later kings and archbishops minted coins until the Danish conquest of York in 866/7. [126] These coins were primarily small silver sceattas, more suitable to small, everyday transactions than larger gold Frankish or Roman coins.[127] They were not a fiat currency, but rather valued by the mass of the silver itself. Larger bullion values can be seen in the silver ingots found in the Bedale Hoard, along with sword fittings and necklaces in gold and silver.[128]

Language

In the time of Bede, there were four vernacular languages in Northumbria: those of the Britons, Scots, Picts, and Northumbrian, and Latin.[129] Northumbrian was one of four distinct dialects of Old English, along with Mercian, West Saxon, and Kentish.[130] Analysis of written texts, brooches, runes and other available sources shows that Northumbrian vowel pronunciation differed from West Saxon.[131] The text of the Northumbrian Gloss of the Lindisfarne Gospel shows signs of anticipating grammar changes which occur in Middle English.[132] One cause of change is language contact. In addition to the five languages present in Bede’s day, Old Norse was added during the period of Scandinavian rule in the ninth century. Vocabulary, syntax, and grammar of the Scandinavians in Northumbria had an influence on the dialect. Similarities in basic vocabulary between Old English and Old Norse may have led to dropping of their different inflectional endings.[133] The number of borrowed words is conservatively estimated to be on order of one thousand.[134] The language of the Celtic Britons was evident in place names in Northumbria. Deira and Bernicia in particular derive their names from Celtic tribal origins.[135]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ In addition to Bernicia and Deira, some other British place names are recorded for important Northumbrian locations. Northumbrian scholar Bede (c. 731) and Welsh chronicler Nennius (ninth-century) both provide British place names for centres of power. Nennius, for example, refers to the royal city of Bamburgh as Din Guaire. [6][7][8][5]

- ↑ Although the Northumbrian king Eric was conflated with King Eric Bloodaxe of Norway in Icelandic sagas, Clare Downham and others have recently argued that the two were separate people. For a discussion of this shift in identification, see Downham, Clare 2004 "Eric Bloodaxe – Axed? The Mystery of the Last Scandinavian King of York", Medieval Scandinavia, vol. 14, pp. 51–77

Notes

- ↑ Bede 1898 Book I, chapter 34

- ↑ Bosworth 1898, p. 725

- ↑ http://www.northumbrianassociation.com/

- ↑ Rollason 2003, p. 44

- 1 2 Rollason 2003, p. 81

- ↑ Bede 1969 Book IV Chapter 19

- ↑ Nennius 2005 para 62

- ↑ Higham 1993, p. 81

- ↑ Hope-Taylor 1983, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Rollason 2003, pp. 83–84

- ↑ Bede 2008 Book II, Chapter 14

- ↑ Bede 2008, p. 93

- ↑ Rollason 2003, pp. 57–64

- ↑ Bede 2008 Book I, Chapter 15

- ↑ Rollason 2003, p. 100

- ↑ Rollason 2003, pp. 45–48

- ↑ Rollason 2003, pp. 48–52

- ↑ Yorke 1990, p. 74

- ↑ Nennius 2005 para 57, 59

- ↑ Nennius 2005 para 59

- 1 2 Yorke 1990, p. 79

- ↑ Bede 2008 Book II, Chapter 1

- ↑ Bede 2008 Book II, Chapter 12

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rollason 2003, p. 7

- ↑ Bede 2008 Book III, Chapter 6

- ↑ Bede 1983 The Life and Miracles of St. Cuthbert, Bishop of Lindisfarne, cap. 24

- ↑ Swanton 1996 793

- ↑ Rollason 2003, p. 211

- 1 2 3 Rollason 2003, p. 212

- ↑ Swanton 1996 865

- ↑ Swanton 1996 866–867

- ↑ Rollason 2003, pp. 212–213

- ↑ Fleming 2010, p. 270

- ↑ Rollason 2003, p. 213

- ↑ Downham 2004 reconsiders the Northumbrian Viking king known as Eric and his perhaps tenuous relationship to the Eric Bloodaxe of the sagas.

- ↑ Rollason 2003, pp. 213,244

- ↑ Rollason 2003, p. 244

- ↑ Rollason 2003, pp. 246–257

- ↑ Fleming 2010, p. 319

- ↑ Arnold 1885

- ↑ Higham 1993, p. 183

- ↑ Rollason 2003, p. 249

- ↑ Arnold 1885 867, 872

- ↑ Swanton 1996 874

- ↑ Higham 1993, p. 181

- ↑ Rollason 2003, p. 249 For the epithet, see also the Annals of Ulster.

- ↑ Kirby 1991, pp. 60–61

- ↑ Bede 2008 Book I chapter 34

- ↑ Bede 2008 II.9–14

- ↑ Higham 1993, p. 124

- ↑ Bede 2008 II.20, III.24

- ↑ Bede 2008 III.1–13

- ↑ Yorke 1990, p. 78-9

- ↑ Yorke 1990

- ↑ Bede 2008 IV.5

- ↑ Venning 2014, p. 132

- ↑ Munch & Olsen 1926, p. 245-251

- ↑ Stevenson 1885, p. 489

- ↑ Lapidge et al. 2013, p. 526

- ↑ Foot 2011, p. 40

- ↑ Foot 2011, p. 40

- ↑ Sturluson 1911, p. 42-43

- ↑ Swanton 1996 MS D 940

- ↑ Swanton 1996 MS D & E 954

- ↑ Arnold 1885 952

- ↑ Petts 2011, pp. 14–27

- ↑ Downham 2007, pp. 40

- ↑ Petts 2011, p. 27

- ↑ Higham 1993, pp. 81–90

- ↑ Fairless 1994, pp. 10–16

- ↑ Clutton-Brock 1899, p. 6

- ↑ Corning 2006, p. 65

- ↑ MacLean 1997, pp. 88–89

- ↑ Fleming 2010, pp. 132–133

- ↑ Fleming 2010, p. 102

- ↑ Bede 2008, p. 96

- ↑ Rollason 2003, p. 207

- ↑ Bede 2008III. 5

- ↑ Rollason 2003, p. 207

- ↑ Fleming 2010, p. 156

- ↑ Rollason 2003, p. 207

- ↑ Fleming 2010, p. 171

- ↑ Butler 1866Volume IX September 6

- 1 2 Lapidge 2006, p. 35

- ↑ Bede 2008, pp. viii–ix

- ↑ Leach 1915, pp. 41

- ↑ Lapidge 2006, p. 41

- ↑ Lapidge 2006, p. 40

- ↑ Corning 2006, p. 114

- ↑ Bede 2008 Book III chapter 25–26

- ↑ Bede 2008 Book III chapter 25–26

- ↑ Rollason 2003, pp. 239

- ↑ Fleming 2010, p. 318

- ↑ Higham 1993, p. 178

- ↑ Rollason 2003, pp. 237–239

- ↑ Rollason 2003, pp. 239

- ↑ Neuman de Vegvar 1990

- ↑ Rollason 2003, pp. 140

- ↑ "Anglo-Saxon art". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2016.

- ↑ "Hiberno-Saxon style". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Otto 1986, p. 72-73

- ↑ Owen-Crocker 1986, p. 28

- ↑ Wormald 1999, p. 29

- ↑ Goffart 2005, p. 238

- ↑ Bede 1969

- ↑ Goffart 1988, p. 245-246

- ↑ Lapidge 2006, p. 44

- ↑ Bede 1969 Book 4 Chapter 24

- ↑ Gradon 1958, p. 9-14

- ↑ Woolf 1955, p. 2-6

- 1 2 Swanton 1996 865

- ↑ Fleming 2010, pp. 213–240

- ↑ Roger of Wendover 1842, pp. 298–299

- ↑ Hadley 2002

- ↑ Karkov 2011, pp. 149–152

- ↑ Berg 1958, pp. 27–30

- ↑ Richards 1991, pp. 121

- ↑ Richards 1991, pp. 123

- ↑ Carver 2005, pp. 36

- ↑ Sawyer 2013, p. 1-4

- ↑ Sawyer 2013, p. 33

- ↑ Sawyer 2013, p. 64-67

- ↑ Allot 1974

- ↑ Alcuinus 2006

- ↑ Wood 2008, p. 28

- ↑ Sawyer 2013, p. 76-77

- ↑ Sawyer 2013, p. 34

- ↑ Ager 2012

- ↑ Bede 1990, pp. 152

- ↑ Baugh 2002, pp. 71

- ↑ Cuesta, Ledesma & Silva 2008, pp. 140

- ↑ Baugh 2002, pp. 160

- ↑ Baugh 2002, pp. 103

- ↑ Baugh 2002, pp. 95

- ↑ Baugh 2002, pp. 75

References

Primary Sources

- Ager, B.M. (2012). "Record ID: YORYM-CEE620 – EARLY MEDIEVAL hoard". Portable Antiquities Scheme. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- Allot, Stephen (1974). Alcuin of York: His Life and Letters. William Sessions Limited. ISBN 978-0900657214.

- Alcuinus, Flaccus Albinus (2006). "Excerpta ex Migne Patrologia Latina: Latinum - Latino - Latin". Documenta Catholica Omnia. Cooperatorum Veritatis Societas. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Bede (1969). Colgrave, Bertram; Mynors, R. A. B., eds. Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822202-5. (Parallel Latin text and English translation with English notes.)

- Bede (2008). Colgrave, Bertram; McClure; Collins, eds. Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199537235.

- Bede (1898). Miller, Thomas, ed. The Old English Version of Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. London: Published for the Early English Text Society by Oxford University Press.

- Bede (1990). Latham, R. E., ed. Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140445657.

- Bede; Eddius Stephanus; Farmer, David Hugh (1983). The Age of Bede. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin. ISBN 9780140444377.

- Arnold, Thomas, ed. (1885). Historia Regum (Anglorum et Dacorum). Symeonis Monachi Opera Omnia. 2. Translated by Stevenson, J. London. pp. 1–283.

- Roger of Wendover (1842). Coxe, Henricus, ed. Flores Historiarum. Sumptibus Societatis.

- Nennius (2005). Historia Brittonum (The History of the Britons). Translated by Rowley, Richard. Cribyn: Llanerch Press. ISBN 9781861431394.

- Stevenson, Joseph, ed. (1885). The Historical Works of Simeon of Durham. The Church Historians of England. 3. London. pp. 425–617.

- Sturluson, Snorri (1964). Hollander, Lee M, ed. Heimskringla; history of the kings of Norway. Austin: Published for the American-Scandinavian Foundation by the University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292732629.

- Swanton, Michael, ed. (1996). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: Dent. ISBN 9780460877374.

Secondary Sources

- "Anglo-Saxon art". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2016.

- Adams, Max (2014). The King in the North : the life and times of Oswald of Northumbria. London: Head of Zeus. ISBN 9781781854204.

- Carver, Martin (2005). The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300-1300. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-125-9.

- Gradon, P.O.E. (1958). "Cynewulf's Elene". London: Methuen.

- Higham, N J (1993). The kingdom of Northumbria : AD 350–1100. Dover, NH: A. Sutton. ISBN 9780862997304.

- Bosworth, Joseph (1898). An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: Based on the Manuscript Collections of the Late Joseph Bosworth. Clarendon Press.

- Butler, Alban (1866). "St. Bega, or Bees, of Ireland, Virgin". The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints. Dublin: James Duffy.

- Baugh, Albert C (2002). A History of the English Language (5 ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415280990.

- Berg, Knut (1958). "The Gosforth Cross". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. Warburg Institute (21 (1/2)): 27–30.

- Clutton-Brock, Arthur (1899). The Cathedral Church of York, Description of its Fabric and a Brief History of the Archi-Episcopal See. London: George Bell & Sons.

- Corning, Caitlin (2006). The Celtic and Roman Traditions : Conflict and Consensus In the Early Medieval Church. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403972996.

- Cuesta, Julia Fernández; Ledesma, Nieves RodrÍguez; Silva, Inmaculada Senra (2008). "Towards a History of Northern English: Early and Late Northumbrian". Studia Neophilologica. 80 (2): 132–159. doi:10.1080/00393270802493217. ISSN 0039-3274.

- Downham, Clare (2004). "Eric Bloodaxe – Axed? The Mystery of the Last Scandinavian King of York". Medieval Scandinavia. 14: 51–77.

- Downham, Clare (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-903765-89-0.

- Fleming, Robin (2010). Britain after Rome: The Fall and Rise 400 to 1070. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140148237.

- Fairless, Peter J (1994). Northumbria's Golden Age : the Kingdom of Northumbria, Ad 547-735. York, England: W. Sessions. ISBN 9781850721383.

- Foot, Sarah (12 July 2011). AEthelstan: The First King of England. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12535-1.

- Goffart, Walter A. (1988). The Narrators of Barbarian History (A. D. 550–800): Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05514-9.

- Hadley, Dawn (2002), "Viking and native: re–thinking identity in the Danelaw", Early Medieval Europe, 11 (1): 45–70, doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00100

- "Hiberno-Saxon style". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- Hope-Taylor, Brian (1983). Yeavering: An Anglo-British Centre of Early Northumbria. Department of the Environmental Archaeological Reports. London: Leicester University Press.

- Karkov, Catherine E. (2011). The Art of Anglo-Saxon England. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-628-5.

- Kirby, D. P. (January 1991). The Earliest English Kings. Unwin Hyman. ISBN 978-0-04-445692-6.

- Lapidge, Michael (26 January 2006). The Anglo-Saxon Library. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-153301-3.

- Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (2 October 2013). Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-31609-2.

- Leach, Arthur Francis (1915). The Schools of Medieval England. Macmillan.

- MacLean, Douglas (1997). "King Oswald's wooden Cross at Heavenfield in Context". In Catherine E. Karkov; Michael Ryan; Robert T. Farrell. The Insular Tradition: A Resource Manual. SUNY Press. pp. 79–98. ISBN 978-0-7914-3455-0.

- Munch, Peter Andreas; Olsen, Magnus Bernhard (1926). Norse mythology: legends of gods and heroes. The American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- Gradon, P.O.E., ed. (1958). Cynewulf's Elene. London: Methuen.

- Neuman de Vegvar, Carol L. (1990). The Northumbrian Golden Age: The Parameters of a Renaisssance. University Microfilms.

- Nordenfalk, Carl (1976). Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Painting: Book illumination in the British Isles 600–800. New York: George Braziller. ISBN 978-0-8076-0825-8.

- Owen-Crocker, Gale R. (1986). Dress in Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Pächt, Otto (1986). Book Illumination in the Middle Ages: An Introduction. H. Miller Pub. ISBN 978-0-19-921060-2.

- Petts, David, Dr.; Turner, Sam, Dr. (2011). Early Medieval Northumbria: Kingdoms and Communities, AD 450-1100. Isd. ISBN 978-2-503-52822-9.

- Rollason, David (25 September 2003). Northumbria, 500-1100: Creation and Destruction of a Kingdom. Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81335-8.

- Richards, J. D. (1 January 1991). Book of Viking Age England. B.T. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-6519-8.

- Schapiro, Meyer (1980). Selected Papers, volume 3, Late Antique, Early Catholic and Mediaeval Art. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-2514-1.

- Sawyer, Peter (2013). The Wealth of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199253937.001.0001. ISBN 9780199253937.

- Stenton, Frank M. (7 June 2001). Anglo-Saxon England. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Goffart, Walter (2005). The narrators of barbarian history (A.D. 550-800) : Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon. Notre Dame, Ind: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 9780268029678.

- Venning, Timothy (30 January 2014). The Kings & Queens of Anglo-Saxon England. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-2459-4.

- Williams, Ann; Alfred P. Smyth; D. P. Kirby (1991). "Athelstan, king of Wessex 924-39". A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain: England, Scotland, and Wales, C. 500-c. 1050. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-85264-047-7.

- Woodman, D. A. (March 2015). "Charters, Northumbria and the Unification of England in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries". Northern History. LII (1). OCLC 60626360.

- Wood, Ian (2008). "Thrymas, Sceattas and the Cult of the Cross". Two Decades of Discovery. Studies in Early Medieval Coinage. 1. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 23–30. ISBN 978-1-84383-371-0.

- Woolf, Rosemary (1955). "Juliana". London: Methuen.

- Wormald, Patrick (1999). The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-13496-4.

- Yorke, Barbara (1 January 1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. Seaby. ISBN 978-1-85264-027-9.

External links

- Lowlands-L, An e-mail discussion list for those who share an interest in the languages & cultures of the Lowlands

- Lowlands-L in Nothumbrian

- Northumbrian Association

- Northumbrian Language Society

- Northumbrian Small Pipes Encyclopedia

- Northumbrian Traditional Music

- Visit Northumberland – The Official Visitor Site for Northumberland