Battle of Majuba Hill

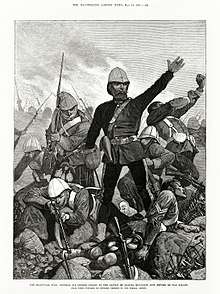

The Battle of Majuba Hill (near Volksrust, South Africa) on 27 February 1881 was the final and decisive battle of the First Boer War. It was a resounding victory for the Boers and the battle is considered to have been one of the most humiliating defeats of British arms in history.[1] Maj. Gen. Sir George Pomeroy Colley occupied the summit of the hill on the night of 26–27 February 1881. Colley's motive for occupying Majuba Hill may have been anxiety that the Boers would soon occupy it themselves, Colley having witnessed their trenches being dug in the direction of the hill.[2] The Boers believed that he might have been attempting to outflank their positions at Laing's Nek. The hill was not considered to be scalable by the Boers, for military purposes, and hence it may have been Colley's attempt to emphasize British power and strike fear into the Boer camp.[3]

The Battle

The bulk of the 405 British soldiers occupying the hill were 171 men of the 58th Regiment with 141 men of the 92nd Gordon Highlanders, and a small naval brigade from HMS Dido. Gen. Colley had brought no artillery up to the summit nor did he order his men to dig in, against the advice of several of his subordinates, expecting that the Boers would retreat when they saw their position on the Nek was untenable.[4] However, the Boers quickly formed a group of storming parties, led by Nicolas Smit, from an assortment of volunteers from various commandos, totaling at least 450 men, maybe more, to attack the hill.

By daybreak at 4:30, the 92nd Highlanders covered a wide perimeter of the summit, while a handful occupied Gordon's Knoll on the right side of the summit. Oblivious to the presence of the British troops until the 92nd Gordon Highlanders began to yell and shake their fists, the Boers began to panic, fearing an artillery attack.[5] Three Boer storming groups of 100-200 men each began a slow advance up the hill. The groups were led by Field Cornet Stephanus Roos, Commandant D.J.K. Malan and Commandant Joachim Ferreira. The Boers, being the better marksmen, kept their enemy on the slopes at bay while groups crossed the open ground to attack Gordon's Knoll, where at 12:45 Ferreira's men opened up a tremendous fire on the exposed knoll and captured it. Colley was in his tent when he was informed of the advancing Boers but took no immediate action until after he had been warned by several subordinates of the seriousness of the attack.[3]

Over the next hour, the Boers poured over the top of the British line and engaged the enemy at long range, refusing close combat action, and picking off the British soldiers one-by-one.[6] The Boers were able to take advantage of the scrub and high grass that covered the hill, something the British were not trained to do. It was at this stage that British discipline began to wane, and panicking troops began to desert their posts, unable to see their opponents and being given very little in the way of direction from officers.[7] When more Boers were seen encircling the mountain, the British line collapsed and many fled pell-mell from the hill. The Gordons held their ground the longest, but once they were broken the battle was over. The Boers were able to launch an attack which shattered the already crumbling British line.

Aftermath

Amidst great confusion and with casualties among his men rising, Colley attempted to order a fighting retreat, but he was shot and killed by Boer marksmen. The rest of the British force fled down the rear slopes of Majuba, where more were hit by the Boer marksmen, who had lined the summit in order to fire at the retreating foe. An abortive rearguard action was staged by the 15th Hussars and 60th Rifles, who had marched from a support base at Mount Prospect, although this made little impact on the Boer forces. A total of 285 Britons were killed, captured, or wounded, including Capt. Cornwallis Maude, son of government minister Cornwallis Maude, 1st Earl de Montalt.[3]

As the British were fleeing the hill, many were picked off by the superior rifles and marksmen of the Boers. Several wounded soldiers soon found themselves surrounded by Boer soldiers and gave their accounts of what they saw; many Boers were young farm boys armed with rifles. This revelation proved to be a major blow to British prestige and Britain's negotiating position, for professionally trained soldiers to have been defeated by young farmboys led by a smattering of older soldiers. [3]

Notability

Although small in scope, the battle is historically significant for four reasons:

- It led to the signing of a peace treaty, and later the Pretoria Convention, between the British and the reinstated South African Republic, ending the First Boer War.

- The fire and movement ("vuur en beweeg" in Afrikaans) tactics employed by the Boers, especially Commandant Smit in his final assault on the hill, were years ahead of their time.

- Coupled with the defeats at Laing's Nek and Schuinshoogte, this third crushing defeat at the hands of the Boers ratified the strength of the Boers in the minds of the British, arguably to have consequences in the Second Anglo-Boer War, when "Remember Majuba" would become a rallying cry.

- Gen. Joubert viewed the aftermath of the battle and noted that the British rifles were sighted at 400-600 yards when the battle raged at about 50-100 yards, as the British officers had not told the troops to alter their weapons and, as a result, they were shooting downhill over the heads of the enemy, who had scant shelter.

Some notable British historians, although not all agree, claim that this defeat marked the beginning of the decline of the British Empire. Since the American Revolution, Great Britain had never signed a treaty on unfavorable terms with anyone and had never lost the final engagements of the war. In every preceding conflict, even if the British suffered a defeat initially, they would retaliate with a decisive victory. The Boers showed that the British were not the invincible foe the world feared.[3]

Notes

- ↑ "It can hardly be denied that the Dutch raid on the Medway vies with the Battle of Majuba in 1881 and the Fall of Singapore in 1942 for the unenviable distinctor of being the most humiliating defeat suffered by British arms." – Charles Ralph Boxer: The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th Century, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London (1974), p.39

- ↑ "The rapid strides that had been made by the Boers in throwing up entrenchments on the right flank of their position, and the continuance of these works in the same direction upon the lower slopes on the Majuba hill during the days subsequent to his return, induced him to believe that if the hill was to be seized before it was occupied and probably fortified by the Boers that is must be done at once." - The National Archives, WO 32/7827, From Lt. Col. H. Stewart, A.A.G., to the General Officer Commanding, Natal and Transvaal, Newcastle, Natal, 4th April 1881. Report of the action on Majuba Hill, 27th February.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Farwell, Byron (2009). Queen Victoria's Little Wars. Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 9781848840157.

- ↑ Donald Featherstone, Victorian Colonial Warfare - Africa, p. 58.

- ↑ Martin Meredith, Diamonds Gold and War, (New York: Public Affairs, 2007):162

- ↑ Donald Featherstone, Victorian Colonial Warfare - Africa, p. 60.

- ↑ Donald Featherstone, Victorian Colonial Warfare - Africa, pp. 60-61.

References

- Donald Featherstone, Victorian Colonial Warfare - Africa (London: Blandford, 1992)

- Martin Meredith, Diamonds Gold and War, (New York: Public Affairs, 2007):162

- The South African Military History Society Journal vol 5 no 2. Details the battle.

- Jan Morris, Heaven's Command, (London: Faber and Faber,1998) pp 442–445.

Further reading

- Castle, Ian (1996). Majuba 1881: The Hill of Destiny. Osprey Campaign Series. #45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-503-9.

- Laband, John. The Transvaal Rebellion: The First Boer War, 1880-1881 (Routledge, 2014).

- Laband, John. The Battle of Majuba Hill: The Transvaal Campaign, 1880-1881 (Helion and Company, 2018).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Majuba. |