Nichiren

| Nichiren (日蓮) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Denomination | Nichiren Buddhism |

| School |

Mahayana Tendai |

| Lineage |

Gautama Buddha Tiantai (Zhiyi) Saichō[1] |

| Education | Kiyozumi-dera Temple (Seichō-ji), Enryaku-ji Temple on Mount Hiei |

| Other names |

• Dai-Nichiren (大日蓮) • Nichiren Daishōnin (日蓮大聖人) • Nichiren Shōnin (日蓮聖人) Nichiren Great Bodhisattva |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | Japanese[7] |

| Born |

16 February 1222 Chiba Prefecture, Japan |

| Died |

October 13, 1282 (aged 60) Ota Ikegami Daibo Hongyoji |

| Religious career | |

| Teacher | Dōzenbo of Seichō-ji Temple[8] |

Nichiren (日蓮; born as Zennichimaro (善日麿), Dharma name: Rencho - 16 February 1222[9][10] – 13 October 1282) was a Japanese Buddhist priest who lived during the Kamakura period (1185–1333) and founded Nichiren Buddhism, a branch school of Mahayana Buddhism.[11][12][13]

Nichiren was highly controversial in his day [14][15]:1 and was known for preaching that the Lotus Sutra, alone contains the highest truth of Buddhist teachings and represents the effective teaching for the Third Age of Buddhism. He declared that social and political peace are dependent on the quality of the belief system that is upheld in a nation. He advocated the repeated recitation of the Sutra's title, Nam(u)-myoho-renge-kyo. In addition, he held that the historical Shakyamuni Buddha was the manifestation of a Buddha-nature that is equally accessible to all. He insisted that those who claim to be believers of the Sutra must propagate it even in the face of persecution.[16][17][18][19][20][21][22]

Nichiren was a prolific writer and his biography, temperament, and the evolution of his thinking has been primarily gleaned from his own writings.[23]:99[24] He launched his teachings in 1253, advocating an exclusive return to the Lotus Sutra as based on its original Tendai interpretations. His 1260 treatise Risshō Ankoku Ron (立正安国論) (On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Security of the Land) argued that a nation that embraces the Lotus Sutra will experience peace and prosperity whereas rulers who support inferior religious teachings invite disorder and disaster into their realms.[14]:88[25] In a 1264 essay he stated that the title of the Lotus Sutra, "Nam(u)-myoho-renge-kyo," encompasses all Buddhist teachings and its recitation leads to enlightenment.[16]:328 As a result of his adamant stance he experienced severe persecution imposed by the Kamakura Shogunate and consequently began to see himself as "bodily reading the Lotus Sutra (Jpn. Hokke shikidoku)."[8]:252[26] In some of his writings during a second exile (1271-1274) he began to identify himself with the key Lotus Sutra characters Sadāparibhūta and Visistacaritra[14]:99,100 and saw himself in the role of leading a vast outpouring of Bodhisattvas of the Earth.[27]

In 1274, after his two predictions of foreign invasion and political strife were seemingly actualized by the first attempted Mongol invasion of Japan along with an unsuccessful coup within the Hōjō clan, Nichiren was pardoned by the Shogunate authorities and his advice was sought but not heeded.[5]:9–10 The Risshō Ankoku Ron in which he first predicted foreign invasion and civil disorder is now considered by Japanese historians to be a literary classic illustrating the apprehensions of that period. In 1358 he was bestowed the title Nichiren Dai-Bosatsu (日蓮大菩薩) (Great Bodhisattva Nichiren) by Emperor Go-Kōgon[28] and in 1922 the title Risshō Daishi (立正大師) (Great Teacher of Rectification) was conferred posthumously by imperial edict.[29]

Nichiren remains a controversial figure among modern scholars who cast him as either a fervent nationalist or a social reformer with a transnational religious vision.[30] Critical scholars have used words such as intolerant, nationalistic, militaristic, and self-righteous to portray him.[31] On the other hand, Nichiren has been presented as a revolutionary,[32] a classic reformer,[33]:403 and as a prophet.[33][34] His prophecy has been compared to that of the Old Testament prophets,[35] Martin Luther,[36][37] Muhammad,[38] and Jesus[39] with all sharing similar rebellious and revolutionary drives to reform degeneration in their respective societies.

Today, Nichiren Buddhism includes traditional temple schools such as the confederation of Nichiren-shū temples and Nichiren Shōshū, as well as modern lay movements such Kenshōkai, Shōshinkai, Risshō Kōsei Kai, Honmon Butsuryū-shū, Kempon Hokke, and Soka Gakkai. Each group has varying views of Nichiren's teachings [21] with interpretations of Nichiren's identity ranging from the reincarnation of bodhisattva Visistacaritra to the primordial or "true" (本仏: Honbutsu) Buddha of the Latter Day of the Law.[40][41][42][43]

Biography

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism in Japan |

|---|

|

Nichiren's hagiography has been constructed from the many extant letters and treatises he wrote. In some cases the originals have been lost but copies have become part of the Nichiren corpus. The authenticity of some of these latter works has been challenged by various schools and scholars.

The first biography of Nichiren did not appear until more than 200 years after his death. Beyond his writings there is a lack of primary sources about Nichiren. Several unsubstantiated stories have found their way into some biographies about him and are reflected in various forms of artwork.[44] There is a modern effort among Nichiren scholars to apply historiographical methodology to create new biographies.[45][46][8]:442

Birth

According to the lunar Chinese calendar, Nichiren was born on 27th of the first month in 1222, which is 16 February in the Gregorian calendar.[47]

Nichiren was born in the village of Kominato (today part of the city of Kamogawa), Nagase District, Awa Province (within present-day Chiba Prefecture). Accounts of his lineage vary. Nichiren described himself as "the son of a Sendara (despised outcast), "a son born of the lowly people living on a rocky strand of the out-of-the-way sea," and "the son of a sea-diver." Although his writings reflect a fierce pride of his lowly birth, believers who followed began to ascribe to him a more noble lineage, perhaps to attract more adherents.[48][49] Some claim his father was a rōnin,[50] a manorial functionary (shokan),[15]:5 or a political refugee.[51][52]

Nichiren's father was Mikuni-no-Tayu Shigetada, also known as Nukina Shigetada Jiro (d. 1258) and his mother was Umegiku-nyo (d. 1267). On his birth, his parents named him Zennichimaro (善日麿) which has variously been translated into English as "Splendid Sun" and "Virtuous Sun Boy" among others.[53] The exact site of Nichiren's birth is believed to be submerged off the shore from present-day Kominato-zan Tanjō-ji (小湊山 誕生寺), a temple in Kominato that commemorates Nichiren's birth.

Buddhist education

Between the years 1233 and 1253 Nichiren engaged in an intensive study of all of the ten schools of Buddhism prevalent in Japan at that time as well as the Chinese classics and secular literature. During these years, he became convinced of the preeminence of the Lotus Sutra and in 1253 returned to the temple where he first studied to present his findings.[54]:129[55][56][57][58][14]:90

In a letter written to a disciple and dated the 6th day of the 9th month of the Kōan Era (1271), Nichiren outlined his rationale for deeply studying Buddhism:

[D]etermined to plant a seed of Buddhahood and attain Buddhahood in this life, just as all other people, I relied on Amida Buddha and chanted the name of this Buddha since childhood. However, I began doubting this practice, making a vow to study all the Buddhist sutras, commentaries on them by disciples, and explanatory notes by others[.][59]

Nichiren began his Buddhist study at a temple of the Tendai school, Seichō-ji (清澄寺, also called Kiyosumi-dera), at twelve years old.[60] He was formally ordained at sixteen years old and took the Buddhist name Zeshō-bō Renchō (是生房蓮長), Renchō meaning "Lotus Growth." He left Seichō-ji for Kamakura where he studied Pure Land Buddhism, a school that stressed salvation through nianfo (Japanese nembutsu) or the invocation of Amitābha (Japanese Amida) and then studied Zen which had been growing in popularity in both Kamakura and Kyoto. He next traveled to Mount Hiei, the center of Japanese Tendai Buddhism, where he scrutinized the school's original doctrines and its subsequent incorporation of the theories and practices of Pure Land and Esoteric Buddhism. Finally he studied at Mount Kōya, the center of Shingon esoteric Buddhism, and in Nara where he studied its six established schools especially the Ritsu sect which emphasized strict monastic discipline.[61][62]:243–245

Declaration of Nam(u) Myoho Renge Kyo

According to one of his letters, Nichiren returned to Seicho-ji Temple on 28 April 1253 to lecture on his twenty years of scholarship.[62]:246 What followed was his first public declaration of Nam(u) Myoho Renge Kyo. This marked the start of his campaign to return Tendai to the exclusive reliance of the Lotus Sutra and his efforts to convert the entire Japanese nation to this belief.[35]:233 Through this declaration he attempted to make profound Buddhist theory practical and actionable so ordinary people could reveal their highest state of life within their own lifetime in the midst of day-to-day realities.[63]

At the same event, according to his own account and subsequent hagiography, he changed his name to Nichiren, an abbreviation of Nichi (日 "Sun") and Ren (蓮 "Lotus").[64] Nichi represents both the light of truth and the Sun Goddess or Japan. Ren signifies the Lotus Sutra. Nichiren envisioned Japan as the country where the true teaching of Buddhism would be revived and the starting point for its worldwide spread.[65]

At his lecture, it is construed, Nichiren vehemently attacked Honen, the founder of Pure Land Buddhism, and its practice of chanting the Nembutsu, Nam(u) Amida Butsu. It is likely he also denounced the core teachings of Seicho-ji which had incorporated non-exclusive Lotus Sutra teachings and practices. In so doing he earned the animosity of the local steward, Hojo Kagenobu, who attempted to have Nichiren killed. Modern scholarship suggests that events unfolded not in a single day but over a longer period of time and had social, and political dimensions. Nichiren developed a base of operations in Kamakura and he converted several Tendai priests, directly ordained others, and attracted lay disciples who were drawn mainly from the strata of the lower and middle samurai class. Their households provided Nichiren with economic support and became the core of Nichiren communities in several locations in the Kanto region of Japan.[62]:246-247

First remonstration to the Kamakura government

Nichiren arrived in Kamakura in 1254. Between 1254 and 1260 half of the population had perished due to a tragic succession of calamities including drought, earthquakes, epidemics, famine, fires, and storms.[62]:432#49 Nichiren sought scriptual references to explain the unfolding of natural disasters and then wrote a series of works which, based on the Buddhist theory of the non-duality of the human mind and the environment, attributed the sufferings to the weakened spiritual condition of people which caused the Kami (protective forces or traces of the Buddha) to abandon the nation. The root cause of this, he argued, was the widespread decline of the Dharma due to the mass adoption of the Pure Land teachings.[62]:249-250[66]:124-125

The most renowned of these works, considered his first major treatise, was the Risshō Ankoku Ron (立正安国論), "Treatise On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land."[note 1] Nichiren submitted it to Hōjō Tokiyori, the de facto leader of the Kamakura shogunate, and was the first of his three remonstrations with government authorities. In it he argued the necessity for "the Sovereign to recognize and accept the singly true and correct form of Buddhism (i.e., 立正: risshō) as the only way to achieve peace and prosperity for the land and its people and end their suffering (i.e., 安国: ankoku)."[68][69][70]

The treatise takes the form of a 10-part dialogue between a fictional Buddhist wise man, presumably Nichiren, and a visitor who laments the tragedies that have hit the nation. The wise man answers the guest's questions and after a heated exchange gradually leads him to enthusiastically embrace the vision of a country grounded firmly on the ideals of the Lotus Sutra. In this writing Nichiren displays a skill in using analogy, anecdote, and detail to persuasively appeal to an individual's unique personality, experiences, and level of understanding.[71][16]:328

In making his arguments the master extensively quotes from a variety of Buddhist sutras and commentaries. In his future writings Nichiren continued to utilize the same sutras and commentaries, effectively forming a canon of sources out of the Buddhist library which he deemed supportive of the Lotus Sutra.[71] This canon draws on several Buddhist sutras with apocalyptic or nation-protecting prophecies including the Konkomyo, Daijuku, Ninno, Yakushi, and Nirvana sutras.[71]:330-334

In its conclusion Nichiren urgently insists that the ruler must cease all financial support for schools promoting inferior teachings.[71]:334 Otherwise, he warns, as predicted by the sutras, the continued influence of inferior teachings would result in the occurrence of even more natural disasters as well as the outbreak of civil strife and foreign invasion.[16]:328

Nichiren submitted his treatise on 16 July 1260 but it drew no official response. It did, however, prompt a severe backlash from the Buddhist priests of other schools. Nichiren was challenged to a debate with leading Kamakura prelates in which, by his account, they were swiftly dispatched. Their lay followers, however, attacked him on multiple occasions including an effort to kill him at his dwelling, forcing him to leave Kamakura. His critics had influence with key governmental figures and spread slanderous rumors about him. One year after he submitted the Rissho Ankoku Ron the authorities had him arrested and exiled to the Izu peninsula.[62]:251

Nichiren's Izu exile lasted two years. In his extant writings from this time period, Nichiren began to focus on the "third realm" (daisan hōmon), chapters 10-22 of the Lotus Sutra. Nichiren here begins to emphasize the purpose of human existence as the practice of the bodhisattva ideal in the real world which entails undertaking struggle and manifesting endurance. He suggests that he is a model of this behavior, a "votary" of the Lotus Sutra.[72][62]:252

Upon being pardoned in 1263 Nichiren returned to Kamakura. On November 1264 he was ambushed and nearly killed at Komatsubara in Awa Province by a force led by Lord Tōjō Kagenobu. For the next few years he preached in provinces outside of Kamakura but returned in 1268. At this point the Mongols sent envoys to Japan demanding tribute and threatening invasion. Nichiren sent 11 letters to influential leaders reminding them about his predictions in the Rissho Ankoku Ron.[5]:7-8

Attempt at execution

The threat and execution of Mongol invasion was the worst crisis in pre-modern Japanese history. In 1269 Mongol envoys again arrived to demand Japanese submission to their hegemony and the bakufu responded by mobilizing military defenses. The role of Buddhism in "nation-protection" (chingo kokka) was long established in Japan at this time and the government galvanized prayers from Buddhist schools for this purpose. Nichiren and his followers, however, felt emboldened that the predictions he had made in 1260 of foreign invasion seemingly were being fulfilled and more people joined their movement. Daring a rash response from the bakufu, Nichiren vowed in letters to his followers that he was giving his life to actualize the Lotus Sutra. He accelerated his polemics against the non-Lotus teachings the government had been supporting at the very time it was attempting to solidify national unity and resolve. In a series of letters he directly provoked leading prelates of Kamakura temples that the Hojo family patronized, criticized the substance of Zen which was popular among the samurai class, critiqued the esoteric practices of Shingon just as the government was invoking them, and condemned the rationality underlying Risshū as it was enjoying a revival.[8]:454-455[62]:257 His actions have been described as a high form of altruisim[73] or the ravings of a fanatic and madman.[74]

His claims drew the ire of the influential religious figures of the time and their followers, especially the influential Shingon priest Ryōkan|Ryōkan (良観). In September 1271, after a fiery exchange of letters with him, Nichiren was summoned for questioning by Hei no Saemon (平の左衛門, also called 平頼綱 Taira no Yoritsuna), the deputy chief of the Hojo clan's Board of Retainers. Nichiren used this as an opportunity to make his second remonstration to the government.[75][62]:257

Two days later, on September 12, Hei no Saemon and a group of soldiers abducted Nichiren from his hut at Matsubagayatsu, Kamakura with the intent of arresting and beheading him. He was brought to Tatsunukuchi beach in Shichirigahama for execution. According to Nichiren's account, an astronomical phenomenon, "a brilliant orb as bright as the moon," arced over the execution grounds, terrifiying Nichiren's executioners into inaction.[76] The incident is known as the Tatsunokuchi Persecution and is regarded as a turning point in Nichiren's lifetime called Hosshaku kenpon (発迹顕本), translated as "casting off the transient and revealing the true" or "Outgrowing the provisional and revealing the essential."[77]

Second banishment and exile

Unsure of what to do with Nichiren, Hei no Saemon decided to banish him to Sado, Niigata island in the Sea of Japan known for its particularly severe winters where exilers do not survive.

This second exile lasted for three years caused him poor health, which later represented one of the most important and productive segments of his life. While on Sado, he won many devoted converts and wrote two of his most important doctrinal treatises, the Kaimoku Shō (開目抄: "On the Opening of the Eyes")[78] and the Kanjin no Honzon Shō (観心本尊抄: "The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind")[68][79] as well as numerous letters and minor treatises whose content containing critical components of his teaching.

The Gohonzon

During his 1272 exile on Sado island, Nichiren inscribed the first Gohonzon (御本尊). He inscribed several during the course of many years. In addition, more than a hundred Gohonzon preserved today are attributed to Nichiren, of which several are prominently retained by the Nichiren-shū in Yamanashi Prefecture.

Hokkekō believers claim that on October 12, 1279 he inscribed the Dai Gohonzon for all humanity after the execution of the three Atsuhara farmers.[80] The Dai Gohonzon is enshrined currently at the Tahō Fuji Dai-Nichirenge-Zan Taiseki-ji, informally known as the Head Temple Taiseki-ji of the Nichiren Shōshū Order of Buddhism, located at the foot of Mount Fuji in Fujinomiya, Shizuoka.

Return to Kamakura

Nichiren was pardoned in February 1274 and returned to Kamakura city in late March. He was again interviewed by Hei no Saemon, who became interested in Nichiren's prediction of an invasion by the Mongols. Mongol messengers demanding Japan's fealty had frightened the authorities into believing that Nichiren's prophecy of foreign invasion would materialize (which it later did in October of that year; see Mongol invasions of Japan). Nichiren, however, used the audience as yet another opportunity to remonstrate with the government.

Retirement to Mount Minobu

With the exception of a few short journeys, Nichiren spent the rest of his life in a self-imposed exile at Mount Minobu, a location 100 miles west of Kamakura.[81][82][83] There he led a widespread movement of followers in Kanto and Sado mainly through prolific letter-writing. During the so-called "Atsuhara affair" of 1279 when governmental attacks were aimed at Nichiren's followers rather than himself, Nichiren's letters reveal an assertive and well-informed leader who provided detailed instructions through a sophisticated network of disciples serving as liaisons between Minobu and other affected areas in Japan. He also showed the ability to provide a compelling narrative of events that gave his followers a broad perspective of what was unfolding.[84]

Most of the extant letters of Nichiren were written during his years at Minobu.[85] Two of his works from this period are the Senji Shō (撰時抄: "The Selection of the Time")[86] and the Hōon Shō (報恩抄: "On Repaying Debts of Gratitude"),[87] which, along with his Risshō Ankoku Ron (立正安国論: "On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land"), Kaimoku Shō ("The Opening of the Eyes"), and Kanjin no Honzon Shō ("The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind"), constitute his Five Major Writings.

During his years at Minobu Nichiren intensified his attacks on mystical and esoteric practices (mikkyō 褒教) that had been incorporated into the Japanese Tendai school. It becomes clear at this point that he understood that he was creating his own form of Lotus Buddhism.[88]:362

Nichiren and his disciples completed the Myō-hōkke-in Kuon-ji Temple (久遠寺) in 1281.[89]:117

He also inscribed numerous Gohonzon for bestowal upon specific disciples and lay believers. Many of these survive today in the repositories of Nichiren temples such as Taiseki-ji (大石寺) in Fujinomiya, Shizuoka, which has a particularly large collection of scrolls that is publicly aired once a year, along with the dusting of the Dai-Gohonzon (O-mushibarai ceremony) by the High Priest of Nichiren Shoshu in April, as well as the public exposure of the statue of the master in both Mieido and Hoando buildings in November.

Death

Nichiren spent his final years writing, inscribing Gohonzon for his disciples and believers, and delivering sermons. In failing health, he was encouraged to travel to hot springs for their medicinal benefits. He left Minobu in the company of several disciples on September 8, 1282.

On 13 October 1282, Nichiren died in the presence of many disciples and lay believers. His funeral and cremation took place the following day. His disciples left Ikegami with Nichiren's ashes on October 21, reaching Minobu on October 25. Nichiren Shu claims his tomb is sited, as per his request, at Kuon-ji on Mount Minobu while Nichiren Shoshu asserts that his disciples led by Nikko Shonin, described by them as the chief priest of Kuon-Ji temple, brought his ashes along with other articles to Mount Fuji where, they claim, are now enshrined on the left side next to the Dai Gohonzon within the Hoando storage house. [note 2]

Development of Nichiren's teachings

Nichiren's doctrines as well as his level of intensity developed over the course of his career. Some scholars see a clear demarcation once he arrived at Sado Island.[90]:238 Others see a threefold division of thought: up to and through the Izu exile, through the Sado Island exile, and during his years at Minobu.[91]:252-253 Some of his evolving thought can be viewed through the annotations he made in his own personal copy of the Lotus Sutra, the so-called Chū-hokekyō.[91]:363.

Nichiren attributed the turmoils and disasters in society to his personal claim that the Buddhist teachings his time, including the Tendai sect in which he was ordained: "It is better to be a leper who chants Nam(u)-myōhō-renge-kyō than be a chief abbot of the Tendai school".[92][93] Accordingly, the Kamakura period of 13th century Japan in which Nichiren was born was characterised by natural disasters, internal strife and political conflict that he attributed to the third age of Buddhism.[94]

At age 32, Nichiren began to denounce all Mahayana Buddhist schools of his time and by declaring the correct teaching as the Universal Dharma (Nam(u)-Myōhō-Renge-Kyō) and chanting its words as the only path for both personal and social salvation.[95][96]

At the age of 51, Nichiren inscribed his own Gohonzon, the object of veneration or worship in his Buddhism, "never before known", as he described it.[97]

Other contributions of Nichiren to Buddhism were the teaching of "The Five Guides of Propagation",[98] The doctrine of the Three Great Secret Dharmas[99] and the teaching of The Three Proofs[100] for verification of the validity of Buddhist doctrines. There is a difference between Nichiren teachings and almost all schools of Mahayana Buddhism regarding the understanding of the Latter day of the Law, the Mappō. Nichiren believed that the teachings of the Lotus Sutra will flourish for all eternity, and the disciples on Earth will propagate Buddhism in the future.[101]

Nichiren criticized other Buddhist schools for what he viewed as manipulations of the populace for both political and religious control. Citing various Buddhist sutras and commentaries, Nichiren claimed and argued that these Buddhist schools were distorting the religious teachings for their own gain. Furthermore, he stated in his Risshō Ankoku Ron[69] (立正安国論): "Treatise On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land",[note 3][102][103] his first major treatise and the first of three remonstrations with government authorities.

After Nichiren's death, his teachings were interpreted in different ways. As a result, Nichiren Buddhism encompasses several major branches and schools, each with its own doctrine and set of interpretations of Nichiren's teachings.

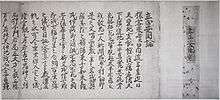

Writings

Many of Nichiren's writings still exist in his original handwriting, both some as complete writings and some as remaining fragments. Other documents survive as copies made by his immediate disciples. Nichiren's existing works number over 700 manuscripts in total, including transcriptions of orally delivered lectures, letters of remonstration and illustrations.[104][105][106][107][108]

Today's Nichiren schools widely disagree which of his writings can be deemed authentic and which are apocryphal.[109]

In addition to treatises written in formal kanbun (漢文) Classical Chinese, Nichiren also wrote expositories and letters to disciples and lay followers in mixed-kanji–kana vernacular as well as letters in simple kana for believers who could not read the more-formal styles, particularly children.

Some of Nichiren's kanbun works, especially the Risshō Ankoku Ron, are considered exemplary of the kanbun style, while many of his letters show unusual empathy and understanding for the down-trodden of his day.

Selected important writings

The five major writings that are common to all Nichiren Buddhism are:[110][111][112]

- On Establishing the Correct teaching for the Peace of the Land (Rissho Ankoku Ron) — written between 1258-1260.[113]

- The Opening of the Eyes (Kaimoku-sho) — written in 1272.

- The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind (Kanjin-no Honzon-sho) — written in 1273.

- The Selection of the Time (Senji-sho) — written in 1275.

- On Repaying Debts of Gratitude (Ho'on-sho) — written in 1276.

Accordingly, the Taiseki-ji of the Nichiren Shōshū revere an additional set of ten major writings. Other Nichiren sects either dispute them as secondary of importance, apocryphal, or forgery:[112]

- On Chanting the Daimoku of the Lotus Sutra (Sho-hokke Daimoku-sho) — Written in 1260.

- On Taking the Essence of the Lotus Sutra (Hokke Shuyo-sho) — written in 1274.

- On the Four Stages of Faith and the Five Stages of Practice (Shishin Gohon-sho) — written in 1277.

- Letter to Shimoyama (Shimoyama Gosho-soku) — written in 1277.

- Questions and Answers on the Object of Devotion (Honzon Mondo-sho) — written in 1278.

Writings to women

Against a backdrop of early Buddhist teachings that deny the possibility of enlightenment to women or reserve that possibility for life after death, Nichiren is highly sympathetic to women. Based on various passages from the Lotus Sutra Nichiren asserts that "Other sutras are written for men only. This sutra is for everyone." [114][115][116]

A great number of letters were addressed to female believers and Nichiren Shu published separate volumes of those writings.[117]

In these letters Nichiren plays particular attention to the instantaneous attainment of enlightenment of the Dragon King's daughter in the "Devadatta" (Twelfth) chapter of the Lotus Sutra and displays deep concern for their fears and worries.[118][119]

In many of his letters to female believers he often complimented them for their in-depth questions about Buddhism while encouraging them in their efforts to attain enlightenment in this lifetime.

Notes

- ↑ [67]

- ↑ "please build my grave on Mount Minobu, because that is where is where I spent nine years reciting the Lotus Sutra to my heart's content. My heart lives forever on Mount Minobu" (Montgomery, Daniel [1991]. Fire in the Lotus, The Dynamic Religion of Nichiren, London: Dai Gohonzon, ISBN 978-1852740917, page 144 [Hakii-dono Gosho, Shingyo Hikkei, 105])

- ↑ Also translated as "On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land" (The Writings of Nichiren), "Establishment of the Legitimate Teaching for the Protection of the Country" (Selected Writings of Nichiren), and others.

References

- ↑ Bloom, Alfred. "Understanding the Social and Religious Meaning of Nichiren". Shin DharmaNet. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ↑ Tōkyō Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan (2003). "Dai Nichiren ten : rikkyō kaishū 750-nen kinen". WorldCat library. Sankei Shinbunsha.

- ↑ "大日蓮出版". 日蓮正宗の専門書を扱う大日蓮出版. Dainichiren Publishing Co., Ltd. 2013.

- ↑ "Daishonin". The Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Yampolsky, Philip B., ed. (1990). Selected writings of Nichiren. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 456. ISBN 0231072600. OCLC 21035153.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Petzold, Bruno, (1995). The classification of Buddhism = Bukkyō kyōhan : comprising the classification of Buddhist doctrines in India, China and Japan 1873-1949. Hanayama, Shinshō, 1898-1995., Ichimura, Shōhei, 1929-, 花山, 信勝(1898-1995). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. 610. ISBN 3447033738. OCLC 34220855.

- ↑ Yamamine, Jun (1952). Nichiren Daishōnin to sono oshie: Nichiren and his doctrine. Kōfukan, University of Michigan.

- 1 2 3 4 Stone, Jacqueline S. (1999). "REVIEW ARTICLE: Biographical Studies of Nichiren" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 26/3–4: 442.

- ↑ "Otanjo-E: Celebrating Nichiren's Birthday". Otanjo-E ceremony. NICHIREN SHOSHU MYOSHINJI TEMPLE. 2016.

- ↑ "Significant SGI Dates" (PDF). VeryPDF Software. VeryPDF Software.

- ↑ Arai, Nissatsu (1893). Outlines of the Doctrine of the Nichiren Sect: With the Life of Nichiren, the Founder of the Nichiren Sect. Harvard University: Central Office of the Nichiren Sect. pp. iii.

- ↑ Reeves, Gene (2008). The Lotus sutra : a contemporary translation of a Buddhist classic. Boston: Wisdom Publications. p. 8. ISBN 9780861719877. OCLC 645422021.

- ↑ Petzold, Bruno, (1995). The classification of Buddhism = Bukkyō kyōhan : comprising the classification of Buddhist doctrines in India, China and Japan 1873-1949. Hanayama, Shinshō, 1898-1995., Ichimura, Shōhei, 1929-, 花山, 信勝(1898-1995). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 609–610. ISBN 3447033738. OCLC 34220855.

- 1 2 3 4 Lopez, Donald S., Jr., (2016). The Lotus Sūtra : a biography. Princeton. p. 77. ISBN 9781400883349. OCLC 959534116.

Among all of the preachers of the dharma of the Lotus Sutra over the past two thousand years, there has been no one like Nichiren. In the long history of the sutra in Japan, he is the most famous--and the most infamous.

- 1 2 Rodd, Laurel Rasplica (1978). Nichiren: A Biography. Arizona State University.

- 1 2 3 4 Rodd, Laurel Rasplica (1995). Ian Philip, McGreal, ed. Great thinkers of the Eastern world : the major thinkers and the philosophical and religious classics of China, India, Japan, Korea, and the world of Islam (1st ed.). New York: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 327. ISBN 0062700855. OCLC 30623569.

- ↑ Jack Arden Christensen, Nichiren: Leader of Buddhist Reformation in Japan, Jain Pub, page 48, ISBN 0875730868

- ↑ Jacqueline Stone, "The Final Word: An Interview with Jacqueline Stone", Tricycle, Spring 2006

- ↑ Stone, Jaqueline (2003). Nichiren, in: Buswell, Robert E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Buddhism vol. II, New York: Macmillan Reference Lib. ISBN 0028657187, p. 594

- ↑ Shuxian Liu,Robert Elliott Allinson, Harmony and Strife: Contemporary Perspectives, East & West, The Chinese University Press, ISBN 9622014127

- 1 2 "Nichiren Buddhism". About.com. Retrieved 2012-09-21.

- ↑ Habito, Ruben L.F. (2005). "Alturism in Japanese Religions: The Case of Nichiren Buddhism". In Neusner, Jacob; Chilton, Bruce. Altruism in World Religions. Georgetown University Press. pp. 141–143. ISBN 1589012356.

- ↑ Iida, Shotara (1987). "Nichiren 700 years later". Modernity and religion. Nicholls, W. (editor). Waterloo, Ont: Published for the Canadian Corp. for Studies in Religion/Corporation canadienne des Sciences religeuses by Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 9780889201545. OCLC 244765387. Lay summary.

- ↑ Stone, Jacqueline I. (1999). "REVIEW ARTICLE: Biographical Studies of Nichiren" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 26/3-4: 442.

- ↑ Fremerman, Sarah. "Letters of Nichiren". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

- ↑ Stone, Jacqueline I (2012). "The sin of slandering the true Dharma in Nichiren's thought" (PDF). Sins and sinners : perspectives from Asian religions. Granoff, P. E., Shinohara, Koichi. Leiden: Brill. pp. 128–130. ISBN 9789004232006. OCLC 809194690.

- ↑ Olson, Carl (2005). "devotional+voices+of+the+pure+land"&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiy4rK2kNvdAhWsVt8KHV0zA-4Q6AEIKTAA#v=snippet&q=nichiren&f=false The different paths of Buddhism : a narrative-historical introduction. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. pp. 196–197. ISBN 0813537789. OCLC 62266054.

- ↑ Matsunaga,, Daigan.; Matsunage, Alicia (1974). Foundation of Japanese Buddhism. Los Angeles: Buddhist Books International. p. 156. ISBN 0914910256. OCLC 1121328.

- ↑ Eliot, Charles (1935). Japanese Buddhism 1862-1931. Parlett, Harold G. (Harold George), Sir, 1869-, Sansom, George Bailey, Sir, 1883-1965. Richmond, Surry: Curzon Press. p. 421. ISBN 0700702636. OCLC 28567705.

- ↑ Habito, Ruben L.F. (1999). [nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/2691 "The Uses of Nichiren in Modern Japanese History"] Check

|url=value (help). Japanese Journal of Religious History. 26:3-4: 438 – via Nanzan Institute. - ↑ See, Tony (2015). "Nichiren and War". Conflict and harmony in comparative philosophy : selected works from the 2013 Joint Meeting of the Society for Asian and Comparative Philosophy and the Australasian Society for Asian and Comparative Philosophy. Creller, Aaron B.,. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 152. ISBN 1443881252. OCLC 922704088.

- ↑ Editors (Winter 2008). "Faith in Revolution". Tricycle Magazine.

- 1 2 King, Sallie B. (1996). "Conclusion: Buddhist Social Activism". Engaged Buddhism: Buddhist Liberation Movements in Asia. Queen, Christopher S and King, Sallie B. (eds.). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. p. 430. ISBN 0791428443.

Nichiren, of course, it is possibly the most outstanding exemplar of the prophetic voice in the entire Buddhist tradition. His fiery denunciations of both the religious and the political status quo of this time and his dogged insistence upon their total displacement earned him the hatred of the powerful and the love of the common people.

- ↑ Anesaki, Masaharu (1916). Nichiren, the Buddhist Prophet. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 3.

If Japan ever produced a prophet or a religious man of prophetic zeal, Nichiren was the man. He stands almost a unique figure in the history of Buddhism, not alone be cause of his persistence through hardship and persecution, but for his unshaken conviction that he himself was the messenger of Buddha, and his confidence in the future of his religion and country. Not only one of the most learned men of his time, but most earnest in his prophetic aspirations, he was a strong man, of combative temperament, an eloquent speaker, a powerful writer, and a man of tender heart. He was born in 1222, the son of a fisherman, and died in 1282, a saint and prophet.

- 1 2 Harvey, Peter (2013). An introduction to Buddhism : teachings, history and practices (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521859424. OCLC 822518354.

- ↑ "Nichiren Buddhism". BBC.

- ↑ Howes, John (2005). Japan's modern prophet : Uchimura Kanzō, 1861-1930. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 111. ISBN 0774811455. OCLC 60670210.

Uchimura compares him to Luther on two counts. The first is his concern over the wrongs of the religious establishment, and the second is his adoption of a single book as the source of his faith. He depended on the Lotus Sutra, Uchimura begins, much as Luther relied on the Bible....In sum, Nichiren was 'a soul sincere to its very core, the honestest of men, the bravest of Japanese.'

- ↑ Obuse, Kieko (2010). Doctrinal Accommodations in Buddhist-Musli Relations in Japan: With Special Reference to Contemporary Japan. Oxford: University of Oxford (dissertation). pp. 177–78, 225.

- ↑ Satomi, Kishio (2007, 1924). Discovery of Japanese Idealism. Oxon: Routledge. pp. 67–77. ISBN 0415245338. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - ↑ World religions in America : an introduction. Neusner, Jacob, 1932-2016. (4th ed.). Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press. 2009. p. 225. ISBN 9781611640472. OCLC 810933354.

- ↑ "Original Buddha". Nichiren Buddhism Library. Soka Gakkai.

- ↑ "True Buddha". Nichiren Buddhism Library. Soka Gakkai.

- ↑ "Latter Day of the Law". Nichiren Buddhism Library. Soka Gakkai.

- ↑ http://www.kuniyoshiproject.com/Illustrated%20Abridged%20Biography%20of%20Koso.htm

- ↑ Gerhart, Karen M. (2009). The material culture of death in medieval Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. p. 115. ISBN 9781441671172. OCLC 663882756.

- ↑ Kinyabara, T.J. (1913). Nichiren Tradition in Pictures. Chicago: Open Court Publishing Company. pp. 344–350.

- ↑ "Conversion of Chinese Lunar Calendar - Gregorian Calendar". asia-home.com.

- ↑ Nakamura, Hajime, (1968). Ways of thinking of Eastern peoples : India, China, Tibet, Japan. Wiener, Philip P. (Philip Paul), 1905-1992. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii. p. 433. ISBN 0585349053. OCLC 47009998.

- ↑ "The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006 pp, 202: Banishment to Sado". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ Broughton, B.L. (1936). "Nichiren Shonin". Maha Bodhi Society of India. 44: 317.

- ↑ Petzold, Bruno (1978). Buddhist Prophet Nichiren: A Lotus in the Sun. Iida, Shotaro and Simmonds, Wendy. University of Virginia, republished by Hokke Jānaru. p. 2.

- ↑ "The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006 pp, 202: Banishment to Sado". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ Robert S. Ellwood, Introducing Japanese religion,Routledge, ISBN 0415774268

- ↑ Green, Paula (2000). "Walking for Peace: Nipponzan Myohoji". Engaged Buddhism in the west. Queen, Christopher S. (Ed.). Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 9780861718412. OCLC 844350971.

- ↑ Jacqueline I. Stone: Review: Biographical Studies of Nichiren, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 26/3-4, pp. 443-444, 1999

- ↑ The Gosho Translation Committee: The Writings of Nichiren, Volume I, Soka Gakkai, 2006. ISBN 4-412-01024-4, introduction p. XXV

- ↑ Anesaki, Masaharu, Nichiren, the Buddhist prophet, Cambridge : Harvard University Press (1916), p.17

- ↑ Jack Arden Christensen, Nichiren: Leader of Buddhist Reformation in Japan, Jain Pub, Page 44, ISBN 0875730868

- ↑ Hori, Kyotsu (1995). Nyonin Gosho: Letters Addressed to Female Followers. Nichiren-shu Overseas Propagation Promotion Association. p. 182.

- ↑ Anesaki, Masaharu, Nichiren, the Buddhist prophet, Cambridge : Harvard University Press (1916), p.13

- ↑ Paolo del Campana, Pier. "Nichiren: Japanese Buddhist monk". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Stone, Jacqueline I. (2003). Original enlightenment and the transformation of medieval Japanese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0824827716. OCLC 53002138.

- ↑ Khoon Choy Lee , Japan: Between Myth and Reality, World Scientific Pub Co, page 104, ISBN 9810218656

- ↑ Anesaki, Masaharu, Nichiren, the Buddhist prophet, Cambridge : Harvard University Press (1916), p.34

- ↑ De Bary, William Theodore (1964). Sources of Japanese tradition. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 215. ISBN 0231086059. OCLC 644425.

- ↑ Deal, William; Ruppert, Brian Douglas. A cultural history of Japanese Buddhism. Chichester, West Sussex, UK. ISBN 9781118608319. OCLC 904194715.

- ↑ Also translated as "On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land" (The Writings of Nichiren) or the "Establishment of the Legitimate Teaching for the Protection of the Country" (Selected Writings of Nichiren).

- 1 2 Murano, Senchu (2003). Two Nichiren Texts (PDF). Berkeley, CA: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. pp. 9–52. ISBN 1886439176.

- 1 2 "The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006 pp, 6-32: On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ A tract revealing the gist of the "rissho angoku-ron", Kyotsu Hori (transl.); Sakashita, Jay (ed.): Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 1, page 163 University of Hawai'i Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8248-2733-3

- 1 2 3 4 Deal, William E. (1999). "Nichiren's Risshō ankoku ron and Canon Formation". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 26 (3/4): 329–330.

- ↑ Tanabe, George J.; Tanabe, Willa J. (1989). The Lotus Sutra in Japanese culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 43, 49. ISBN 0824811984. OCLC 18960211.

Nichiren called this third realm daisan hōmon, meaning the third sphere of 8akyamuni's teaching. The teachings in this realm of the Lotus Sutra emphasize the need to endure the trials of life and to practice the true law. In short, they advocate human activity in the real world, or bodhisattva practices. The eternal Buddha is also considered anew in this context, and it is said that Sakyamuni himself endlessly undertook bodhisattva practices. This third realm emphasizing bodhisattva practices suggests the meaning and purpose of human existence in this world.

- ↑ Habito, Ruben L.F. (2005-11-08). "Altruism in Japanese Religions: The Case of Nichiren Buddhism". In Neusner, Jacob; Chilton, Bruce. Altruism in World Religions. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 1589012356.

- ↑ Petzold, Bruno (1978). Buddhist Prophet Nichiren: A Lotus in the Sun. Hokke Jānaru. p. 1.

- ↑ McIntire, Suzanne; Burns, William E. (2010-06-25). Speeches in World History. Infobase Publishing. p. 102. ISBN 9781438126807.

- ↑ "The Writings of Nichiren", p. 767

- ↑ (Tanabe 2002, p. 357)

- ↑ "The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006, pp. 220-298: The Opening of the Eyes". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ "The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006, pp. 354-382: The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ Causton, Richard: "Buddha in Daily Life, An Introduction to the Buddhism of Nichiren", Random House 2011, p. 241 ISBN 1446489191

- ↑ Habito, Ruben L.F. (1999). [nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/2685 "Bodily Reading of the Lotus Sutra: Understanding Nichiren's Buddhism"] Check

|url=value (help). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 26/3-4: 297. - ↑ Lopez, Donald S. The Lotus Sūtra : a biography. Princeton. p. 101. ISBN 9781400883349. OCLC 959534116.

- ↑ https://www.nichirenlibrary.org/en/wnd-2/Content/234

- ↑ Stone, Jacqueline I. (2014). "The Atsuhara Affair: The Lotus Sutra, Persecution, and Religious Identity in the Early Nichiren Tradition". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 41/1: 165, 176 – via Nanzan Institute.

- ↑ https://www.nichirenlibrary.org/en/wnd-1/Introduction/3#The Life of Nichiren Daishonin

- ↑ "The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006, pp. 538-594: The Selection of the Time". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ "SGI The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006, pp. 41-47: The Four Debts of Gratitude". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ Dolce, Lucia (1999). [nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/nfile/2689 "Criticism and Appropriation: Nichiren's Attitude toward Esoteric Buddhism"] Check

|url=value (help). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 26/3-4 – via Narzan Institute. - ↑ Christensen, Jack Arden (2001). Nichiren : leader of Buddhist reformation in Japan. Fremont, Calif.: Jain Publishing Co. ISBN 9780875730868. OCLC 43030590. Lay summary.

- ↑ Nichiren (2002). Writings of Nichiren Shonin: Doctrine 2. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824825515.

- 1 2

- ↑ (Stone 2003, p. 254)

- ↑ (Stone 2003, pp. 240–1)

- ↑ (Stone 2003, p. 56)

- ↑ The Essence of Nichiren Shu Buddhism, SanJose Temple, page 81/ ISBN 0970592000

- ↑ "The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006, pp. 3-5: On Attaining Buddhahood in This Lifetime". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ "The Real Aspect of the Gohonzon". Nichiren Buddhism Library. Soka Gakkai.

- ↑ "The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006, p. 77: Encouragement of a Sick Person". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ The Essence of Nichiren Shu Buddhism, SanJose Temple, page 84/ ISBN 0970592000

- ↑ "The Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism 2002: Three proofs". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ Asai Endō (1968; translated 1999). Nichiren's View of Humanity: The Final Dharma Age and the Three Thousand Realms in One Thought-Moment, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 26 (3-4), 239-240. See also "The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006, p. 437 Rebuking Slander of the Law". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06. , "The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006, p. 736: On Repaying Depts of Gratitude". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06. and "The Writings of Nichiren I, SGI 2006, p. 903: The Teaching for the Latter Day". Sgilibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-09-06. .

- ↑ Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine I, page 105-155

- ↑ "Living Rissho Ankoku Ron Commentary by Rev. Ryuei". Nichirenscoffeehouse.net. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ↑ Burton Watson and the Gosho Translation Committee: The Writings of Nichiren, Volume I, Soka Gakkai, 2006. ISBN 4-412-01024-4

- ↑ Burton Watson and the Gosho Translation Committee: The Writings of Nichiren, Volume II, Soka Gakkai, 2006. ISBN 4-412-01350-2

- ↑ Kyotsu Hori (transl.): Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine Vol. 1-6, University of Hawai'i Press, 2003-2010

- ↑ Jacqueline I. Stone, Some disputed writings in the Nichiren corpus: Textual, hermeneutical and historical problems, dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1990 PDF (21 MB) retrieved 07/26/2013

- ↑ Sueki Fumehiko: Nichirens Problematic Works, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 26/3-4, 261-280, 1999

- ↑ Listing of Authenticated Gosho (Goibun) of Nichiren

- ↑ Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism, Soka Gakkai, "Five Major Writings"

- ↑ Dharma Flower, Ryuei Michael McCormick (2000), p. 156: "The five most important works of Nichiren. The five major writings are: Rissho ankoku ron (Treatise on Spreading Peace Throughout the Country by Establishing the True Dharma), Kaimoku sho (Open Your Eyes), Kanjin no honzon sho (Spiritual Contemplation and the Focus of Devotion), Senji sho (Selecting the Right Time), and Ho'on sho (Recompense of Indebtedness)."

- 1 2 Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism, Soka Gakkai, "Ten Major Writings".

- ↑ Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism, Soka Gakkai, "Rissho Ankoku Ron".

- ↑ Kurihara, Toshie. 2003. "A History of Women in Japanese Buddhism: Nichiren's Perspectives on the Enlightenment of Women." The Journal of Oriental Studies, vol. 13. p.94 Archived March 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Oguri, Junko. 1987. Nyonin ojo: Nihon-shi ni miru onna no sukui (Women's Capacity to Be Reborn in the Pure Land: Women's Salvation in Japanese History). Jimbun Shoin, p. 122. See also: Oguri, Junko. 1984. "Views on Women's Salvation in Japanese Buddhism" in Young East 10/1, pp 3-11.

- ↑ (WND, p.385)

- ↑ Nyonin Gosho, Letters Addressed to Female Followers, Translated by Nichiren Shu Overseas Ministers in North America, Edited and Compiled by Kyotsu Hori, published 1995 by Nichiren Shu Overseas Propagation Promotion Association

- ↑ Rasplica Rodd, Laurel. "Nichiren's Teachings to Women". Selected Papers in Asian Studies: Western Conference of the Association for Asian Studies. 1 (5): 8–18.

- ↑ The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender,Bernard Faure, ISBN 9781400825615, Princeton University Press, 2009, p.93

Bibliography

- Montgomery, Daniel B. (1991). Fire in the lotus: the dynamic Buddhism of Nichiren. London: Dai Gohonzon. ISBN 978-1852740917.

- Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse (1 May 2003). Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2771-7.

- Nichiren Shoshu International Center (1983). A Dictionary of Buddhist terms and concepts (1st ed.). Tokyo: Nichiren Shoshu International Center. ISBN 978-4888720144.

- Causton, Richard (1985). Buddha in Daily Life: An Introduction to the Buddhism of Nichiren. Random House.

- Christensen, J. A. (2000). Nichiren. Fremont, CA: Jain Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0875730868.

- Harvey, Peter (1992). An introduction to Buddhism : teaching, history and practices (Repr. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0521313339.

- Tamura, Yoshiro (2000). Japanese Buddhism : a cultural history (1st English ed.). Tokyo: Kosei Publ. ISBN 978-4333016846.

- Tanabe, George, ed. (2002). Writings of Nichiren. Tokyo: Nichiren Shū overseas propagation promotion association. ISBN 978-0824825515.

- The English Buddhist Dictionary Committee (2002). The Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism., Tokyo, Soka Gakkai, ISBN 4-412-01205-0

- Nichiren Buddhist Temple of San Jose (1957). Lotus seeds: The Essence of Nichiren Shu Buddhism. San Jose, CA: Nichiren Buddhist Temple of San Jose. ISBN 978-0970592002.

English translations of Nichiren's writings

- The Major Writings of Nichiren. Soka Gakkai, Tokyo, 1999.

- Heisei Shimpen Dai-Nichiren Gosho (平成新編 大日蓮御書: "Heisei new compilation of Nichiren's writings"), Taisekiji, 1994.

- The Writings of Nichiren, Volume I, Burton Watson and the Gosho Translation Committee. Soka Gakkai, 2006, ISBN 4-412-01024-4.

- The Writings of Nichiren, Volume II, Burton Watson and the Gosho Translation Committee. Soka Gakkai, 2006, ISBN 4-412-01350-2.

- The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings, Burton Watson, trans. Soka Gakkai, 2005, ISBN 4-412-01286-7.

- Writings of Nichiren, Chicago, Middleway Press, 2013, The Opening of the Eyes.[1]

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 1, University of Hawai'i Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8248-2733-3.

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 2, University of Hawai'i Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8248-2551-9.

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 3, University of Hawai'i Press, 2004, ISBN 0-8248-2931-X.

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 4, University of Hawai'i Press, 2007, ISBN 0-8248-3180-2.

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 5, University of Hawai'i Press, 2008, ISBN 0-8248-3301-5.

- Writings of Nichiren, Doctrine 6, University of Hawai'i Press, 2010, ISBN 0-8248-3455-0.

- Letters of Nichiren, Burton Watson et al., trans.; Philip B. Yampolsky, ed. Columbia University Press, 1996 ISBN 0-231-10384-0.

- Selected Writings of Nichiren, Burton Watson et al., trans.; Philip B. Yampolsky, ed. Columbia University, Press, 1990, ISBN 0-231-07260-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nichiren. |

- Life of Nichiren by Ryuei Michael McCormick

- Renso Den, An Illustrated Life Story of Nichiren with pictures by K. Touko1920

- An English biography of Nichiren on the website of the Myokanko, a Japanese group associated with Nichiren Shoshu

- Official Soka Gakkai International (SGI) Website

- Official Nichiren Shoshu Website

- Official Nichiren Shu Website

- Official Nichiren Buddhist Association of America Website

- Nichiren - a Man of Many Miracles (日蓮と蒙古大襲来 Nichiren to mōko daishūrai) - 1958 film by Kunio Watanabe.

- ↑ Daisaku Ikeda (2013). "The Opening of the Eyes : Commentaries on the Writings of Nichiren". WorldCat library. Chicago : Middleway Press.