Dashavatara

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

|

Important deities |

|

Sampradayas |

|

|

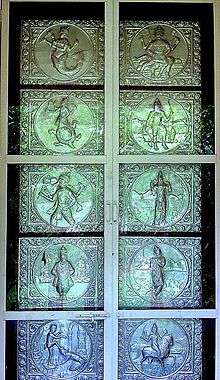

Dashavatara (/ˌdæʃəˈvætərə/; Sanskrit: दशावतार, daśāvatāra) refers to the ten primary avatars of Vishnu, the Hindu god of preservation. Vishnu is said to descend in form of an avatar to restore cosmic order. The word Dashavatara derives from daśa, meaning 'ten', and avatar (avatāra), roughly equivalent to 'incarnation'.

The list of included avatars varies across sects and regions, and no list can be uncontroversially presented as standard. However, most draw from the following set of figures, omitting at least one of those listed in parentheses: Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha, Vamana, Parashurama, Rama, (Krishna, Balarama or Buddha), and Kalki. In traditions that omit Krishna, he often replaces Vishnu as the source of all avatars. Some traditions include a regional deity such as Vithoba or Jagannath in penultimate position, replacing Krishna or Buddha. All avatars have appeared except Kalki, who will appear at the end of the Kali Yuga.

Description

The list of avatars in the Dashavatara varies by region. The following table summarises the position of avatars within the Dashavatara in many but not all traditions. A number in the table indicates the position of the corresponding avatar within the Dashavatara. Two or more numbers separated by commas indicate that the position of the corresponding avatar within the Dashavatara varies between traditions. Bracketed numbers indicate that the corresponding avatar is omitted in some traditions.

| Avatar | Position | Yuga[1] |

|---|---|---|

| Matsya | 1 | Satya Yuga |

| Kurma | 2 | |

| Varaha | 3 | |

| Narasimha | 4 | |

| Vamana | 5 | Treta Yuga |

| Parashurama | 6 | |

| Rama | 7 | |

| Krishna | (8) | Dwapara Yuga |

| Buddha | (9) | Kali Yuga |

| Kalki | (10) |

Etymology

The word Dashavatara derives from daśa, meaning 'ten' and avatar (avatāra), meaning 'incarnation'.

Number of occurrences of these avatars of lord Vishnu are one less than the total number of avatars in previous yuga.

Satya Yuga - Had 4 (Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Narasimha)

Treta Yuga - Had 3 (Vamana, Parshurama, Rama)

Dwapara Yuga- Had 1 (Krishna)

Kali Yuga- Had 1, Yet to have 1 (Lord Buddha, Kalki)

List

- Matsya, the fish. Vishnu takes the form of a fish to save Manu from the deluge (Pralaya), after which he takes his boat to the new world along with one of every species of plant and animal, gathered in a massive cyclone.

- Kurma, the giant tortoise. When the devas and asuras were churning the Ocean of milk in order to get Amrita, the nectar of immortality, the mount Mandara they were using as the churning staff started to sink and Vishnu took the form of a tortoise to bear the weight of the mountain.

- Varaha, the boar. He appeared to defeat Hiranyaksha, a demon who had taken the Earth, or Prithvi, and carried it to the bottom of what is described as the cosmic ocean(much like in ether theory) in the story. The battle between Varaha and Hiranyaksha is believed to have lasted for a thousand years, which the former finally won. Varaha carried the Earth out of the ocean between his tusks and restored it to its place in the universe.

- Narasimha, the half-man/half-lion. The rakshasa (Demon) Hiranyakashipu, the elder brother of Hiranyaksha, was granted a powerful boon from Brahma that he could not be killed by man or animal, inside or outside a room, during day or night, neither on ground nor in air, with a weapon that is either living or inanimate. Hiranyakashipu persecuted everyone for their religious beliefs including his son who was a Vishnu follower.[2] Vishnu descended as an anthropomorphic incarnation, with the body of a man and head and claws of a lion. He disemboweled Hiranyakashipu at the courtyard threshold of his house, at dusk, with his claws, while he lay on his thighs. Narasimha thus destroyed the evil demon and brought an end to the persecution of human beings including his devotee Prahlada, according to the Hindu mythology.[2]

- Vamana, the dwarf. The fourth descendant of Hiranyakashyap, Bali, with devotion and penance was able to defeat Indra, the god of firmament. This humbled the other deities and extended his authority over the three worlds. The gods appealed to Vishnu for protection and he descended as a boy Vamana.[3] During a yajna (यज्ञ) of the king, Vamana approached him and Bali promised him for whatever he asked. Vamana asked for three paces of land. Bali agreed, and the dwarf then changed his size to that of a giant Trivikrama form.[3] With his first stride he covered the earthly realm, with the second he covered the heavenly realm thereby symbolically covering the abode of all living beings.[3] He then took the third stride for the netherworld. Bali realized that Vamana was Vishnu incarnate. In deference, the king offered his head as the third place for Vamana to place his foot. The avatar did so and thus granted Bali immortality and making him ruler of Pathala, the netherworld. This legend appears in hymn 1.154 of the Rigveda and other Vedic as well as Puranic texts.[4][5]

- Parashurama, the warrior with the axe. He is son of Jamadagni and Renuka and received an axe after a penance to Shiva. He is the first Brahmin-Kshatriya in Hinduism, or warrior-saint, with duties between a Brahmin and a Kshatriya. King Kartavirya Arjuna and his army visited the father of Parashurama at his ashram, and the saint was able to feed them with the divine cow Kamadhenu. The king demanded the cow, but Jamadagni refused. Enraged, the king took it by force and destroyed the ashram. Parashurama then killed the king at his palace and destroyed his army. In revenge, the sons of Kartavirya killed Jamadagni. Parashurama took a vow to kill every Kshatriya on earth twenty-one times over, and filled five lakes with their blood. Ultimately, his grandfather, rishi Rucheeka, appeared before him and made him halt. He is a Chiranjivi (immortal), and believed to be alive today in penance at Mahendragiri.

- Rama, the prince and king of Ayodhya. He is a commonly worshipped avatar in Hinduism, and is thought of as the ideal heroic man. His story is recounted in one of the most widely read scriptures of Hinduism, the Ramayana. While in exile from his own kingdom with his brother Lakshman and the God Hanuman, his wife Sita was abducted by the demon king of Lanka, Ravana. He travelled to Lanka, killed the demon king and saved Sita.

- Balarama, the elder brother of Krishna, is regarded generally as an avatar of Shesha. However, Balarama is included as the eighth avatar of Vishnu in the Sri Vaishnava lists, where Buddha is omitted and Krishna appears as the ninth avatar in this list.[6] He is particularly included in the lists where Krishna is removed and becomes the source of all.

- Krishna[7] was the eighth son of Devaki and Vasudeva. A frequently worshipped deity in Hinduism, he is the hero of various legends and embodies qualities such as love and playfulness.

- Buddha: Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, is commonly included as an avatar of Vishnu in Hinduism. Buddha is sometimes depicted in Hindu scriptures as a preacher who deludes and leads demons and heretics away from the path of the Vedic scriptures, but another view praises him a compassionate teacher who preached the path of ahimsa (non-violence).[7][6][8]

- Kalki is described as the final incarnation of Vishnu, who appears at the end of each Kali Yuga. He will be atop a white horse and his sword will be drawn, blazing like a comet. He appears when only chaos, evil and persecution prevails, dharma has vanished, and he ends the kali yuga to restart Satya Yuga and another cycle of existence.[9][10]

Historical development

—Sanctum entrance, Adivaraha cave (7th century), Mahabalipuram;

earliest avatar-related epigraphy[13][14][note 1]

Various versions of the list of Vishnu's avatars exist.[7] Some lists mention Krishna as the eighth avatar and the Buddha as the ninth avatar,[7] while others – such as the Yatindramatadipika, a 17th-century summary of Srivaisnava doctrine[6] – give Balarama as the eighth avatar and Krishna as the ninth.[6] The latter version is followed by some Vaishnavas who don't accept the Buddha as an incarnation of Vishnu.[16]

Buddha

The Buddha was included as one of the avatars of Vishnu under Bhagavatism by the Gupta period between 330 and 550 CE. The mythologies of the Buddha in the Theravada tradition and of Vishnu in Hinduism share a number of structural and substantial similarities.[17] For example, states Indologist John Holt, the Theravada cosmogony and cosmology states the Buddha covered 6,800,000 yojanas in three strides, including earth to heaven and then placed his right foot over Yugandhara – a legend that parallels that of the Vamana avatar in Hinduism. Similarly, the Buddha is claimed in the Theravada mythology to have been born when the dhamma is in decline, so as to preserve and uphold the dhamma. These similarities may have contributed to the assimilation of the Buddha as an avatar of Vishnu.[17]

The adoption of Buddha as an avatar in Bhagavatism was a catalyzing factor in Buddhism's assimilation into Vaishnavism's mythic hierarchy. By the 8th century CE, the Buddha was included as an avatar of Vishnu in several Puranas.[18] This assimilation is indicative of the Hindu ambivalence toward the Buddha and Buddhism.[19] Conversely, Vishnu has also been assimilated into Sinhalese Buddhist culture,[20] and Mahayana Buddhism is sometimes called Buddha-Bhagavatism.[21] By this period, the concept of Dashavatara was fully developed.[22]

Regional versions

In Maharashtra and Goa, Vithoba's image replaces Buddha as the ninth avatar of Vishnu in some temple sculptures and Hindu astrological almanacs.[23] In certain Oriya literary creations from Orissa, Jagannath has been treated as the Ninth avatar, by substituting Buddha.[24]

Krishna

Jayadeva, in his Pralaya Payodhi Jale from the Gita Govinda, includes Balarama and Buddha where Krishna is equated with Vishnu and the source of all avatars.[25]

In traditions that emphasize the Bhagavata Purana, Krishna is the original Supreme Personality of Godhead, from whom everything else emanates. Gaudiya Vaishnavas worship Krishna as Svayam Bhagavan, or source of the incarnations.[26][27][28] The Vallabha Sampradaya and Nimbarka Sampradaya, (philosophical schools) go even further, worshiping Krishna not only as the source of other incarnations, but also Vishnu himself, related to descriptions in the Bhagavata Purana. Mahanubhavas also known as the Jai Kishani Panth, considers Lord Krishna as the supreme God and don't consider the list of Dashavatara while consider another list of Panchavatara (5 Avatars). [29][30]

Thirty-nine avatars are mentioned in the Pañcaratra including the likes of Garuda[31]. [32] However, despite these lists, the commonly accepted number of ten avatars for Vishnu was fixed well before the 10th century CE.[33]

Evolutionary interpretation

Some modern interpreters sequence Vishnu's ten main avatars in a definitive order, from simple life-forms to more complex, and see the Dashavataras as a reflection, or a foreshadowing, of the modern theory of evolution. Such an interpretation was first propounded by Theosophist Helena Blavatsky in her 1877 opus Isis Unveiled, in which she proposed the following ordering of the Dashavataras:[34][35]

- Matsya - fish (Paleozoic era)

- Kurma - amphibious tortoise (Mesozoic era)[34][35]

- Varaha - boar (Cenozoic era)[34][35]

- Narasimha - man-lion, the last animal and semi-human avatar (Cenozoic era)[34][35]

- Vamana - growing dwarf and first step towards the human form

- Parasurama - a hero, but imperfect human form

- Rama - another hero, physically perfect, befriends a speaking monkey deity Hanuman

- Christna ([sic], Krishna)[34][35] - son of non-virgin Devanaguy ([sic], Devaki),[34][35]

- Buddha - the Buddhism founder

- Kalki - yet to happen and the savior, and is like Christian Advent, which Madame Blavatsky believed Christians "undoubtedly copied from the Hindus"[34][35]

Blavatsky believed that the avatara-related Hindu texts were an allegorical presentation of Darwinian evolution.[36] Some Orientalists and reformist Hindus in India picked up this idea to rationalize Hinduism as being consistent with modern science. Keshub Chandra Sen[38] stated in 1882,[34]

The Puranas speak of the different manifestations or incarnations of the Deity in different epochs of the world history. Lo! The Hindu Avatar rises from the lowest scale of life through the fish, the tortoise, and the hog up to the perfection of humanity. Indian Avatarism is, indeed, a crude representation of the ascending scale of Divine creation. Such precisely is the modern theory of evolution.

Similarly Aurobindo regarded "Avataric Evolutionism" as a "parable of evolution", one which does not endorse evolutionism, but hints at "transformative phases of spiritual progress".[39] According to Nanda, the Dashavatara concept has led to some Hindus asserting that their religion is more open to scientific theories, and has not opposed or persecuted scientists midst them like the way Christianity and Islam has.[40] But, adds Nanda, Hinduism has many cosmological theories and even the Vaishnava one with Dashavatara concept does not explicitly teach evolution of species, rather it states an endless cycles of creationism.[40]

The Dashavatara concept appealed to other scholars. Monier Monier-Williams wrote "Indeed, the Hindus were ... Darwinians centuries before the birth of Darwin, and evolutionists centuries before the doctrine of evolution had been accepted by the Huxleys of our time, and before any word like evolution existed in any language of the world."[41] J. B. S. Haldane suggested that Dashavatara gave a "rough idea" of vertebrate evolution: a fish, a tortoise, a boar, a man-lion, a dwarf and then four men (Kalki is not yet born).[42] Nabinchandra Sen explains the Dashavatara with Darwin's evolution in his Raivatak.[43] C. D. Deshmukh also remarked on the "striking" similarity between Darwin's theory and the Dashavatara.[44]

Some Vaishnava Hindus reject this "Avataric Evolutionism" concept. For example, ISKCON's Prakashanand states that this apologeticism degrades the divine status of Rama and Krishna, unduly sequences Rama as inferior to Krishna, both to the Buddha. Rama and Krishna are supremely divine, each right and perfect for the circumstances they appeared in, states Prakashanand.[45]

Notes

- ↑ This 7th century (or early 8th century) inscription is significant for several reasons. It is the earliest known stone inscription about the ten avatars of Vishnu, and prior to that the they are found in older texts. The stone inscription mentions the Buddha as an avatar of Vishnu in a Hindu temple. It also does not mention Krishna, but Balarama consistent with old Hindu and Jain texts of South India, the former equating Krishna to be identical to Vishnu.[13][15]

References

- ↑ J.P. VASWANI (2017). Dasavatara. Jaico Publishing House. pp. 12–14.

- 1 2 Deborah A. Soifer (1991). The Myths of Narasimha and Vamana: Two Avatars in Cosmological Perspective. State University of New York Press. pp. 73–88. ISBN 978-0-7914-0800-1.

- 1 2 3 Deborah A. Soifer (1991). The Myths of Narasimha and Vamana: Two Avatars in Cosmological Perspective. State University of New York Press. pp. 33–36. ISBN 978-0-7914-0800-1.

- ↑ Wendy Doniger (1988). Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism. Manchester University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7190-1866-4. , Wikisource of Griffith's translation

- ↑ Ariel Glucklich (2008). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-0-19-971825-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Carman 1994, p. 211-212.

- 1 2 3 4 Wuaku 2013, p. 148.

- ↑ Literature review of secondary references of Buddha as Dashavatara which regard Buddha to be part of standard list:

- Britannica Balarama

- Britannica

- A Dictionary of Asian Mythology By David Adams Leeming p. 19 "Avatar"

- Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide By Roshen Dalal p. 112 "Dashavatara" ""The standard and most accepted list found in Puranas and other texts is: ... Rama, Krishna, Buddha, Kalki."

- The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M p. 73 "Avatar"

- Hindu Gods and Goddesses By Sunita Pant Bansal p. 27 "Vishnu Dashavatara"

- Hindu Myths (Penguin Books) pp. 62-63

- The Hare Krsnas - Incarnations of the Lord - Dasavatara - Ten Primary Visnu Incarnations

- The Book of Vishnu (see index)

- Seven secrets of Vishnu By Devdutt Pattanaik p. 203 "In the more popular list of ten avatars of Vishnu, the ninth avatar is shown as Buddha, not Balarama."

- A Dictionary of Hinduism p. 47 "Avatara"

- BBC - GCSE Bitesize Avatars

- Gavin D. Flood (13 July 1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- ↑ Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ↑ Wendy Doniger; Merriam-Webster, Inc (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 629. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- ↑ Rao Bahadur H. Krishna Sastri (1926), Two Statues of Pallava Kings and Five Pallava Inscriptions in a Rock temple at Mahabalipuram, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India, Volume 26, pages 5-6

- ↑ D. Kiran Kranth Choudary; C. Udayalakshmi (2006). Rāmāyaṇa in Indian Art and Epigraphy. Harman. p. 19. ISBN 978-81-86622-76-6.

- 1 2

- ↑ Michael Dan Rabe; G. John Samuel (2001). The Great penance at Māmallapuram: deciphering a visual text. Institute of Asian Studies. p. 124. ISBN 978-81-87892-00-7.

- ↑ Nagaswamy, R (2008). Mahabalipuram (Mamallapuram). Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-569373-7.

- ↑ Krishna 2009.

- 1 2 Holt 2013, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Holt 2013, pp. 14-18.

- ↑ Holt 2013, p. 18.

- ↑ Holt 2013, p. 3.

- ↑ Hāṇḍā, Omacanda (1994). Buddhist Art & Antiquities of Himachal Pradesh: Up to 8th Century A.D. Columbia, Mo: South Asia Books. p. 40. ISBN 81-85182-99-X.

- ↑ Indian, History. "(Prabha IAS-IPS Coaching Centre - Indian History 2003 exam - "The crystallization Of the Avatara Concept and the worship of the incarnations of Vishnu were features of Bhagavatism during the Gupta period"". Arumbakkam, Chennai. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2008.

- ↑ Pathak, Dr. Arunchandra S. (2006). "Junnar". The Gazetteers Dept, Government of Maharashtra (first published: 1885). Archived from the original on 16 October 2009. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Mukherjee, Prabhat The history of medieval Vaishnavism in Orissa. P.155

- ↑ Orissa Review

- ↑ Religion of the Hindus By Kenneth W Morgan, D S Sarma p.55

- ↑ Iconography of Balarama By N.P. Joshi p.25

- ↑ Kennedy, M.T. (1925). The Chaitanya Movement: A Study of the Vaishnavism of Bengal. H. Milford, Oxford university press.

- ↑ Flood, Gavin D. (1996). An introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 341. ISBN 0-521-43878-0. Retrieved 2008-04-21. "Early Vaishnava worship focuses on three deities who become fused together, namely Vasudeva-Krishna, Krishna-Gopala and Narayana, who in turn all become identified with Vishnu. Put simply, Vasudeva-Krishna and Krishna-Gopala were worshiped by groups generally referred to as Bhagavatas, while Narayana was worshipped by the Pancaratra sect."

- ↑ Essential Hinduism S. Rosen, 2006, Greenwood Publishing Group p.124 ISBN 0-275-99006-0

- ↑ Sullivan 2001, p. 32.

- ↑ Schrader, Friedrich Otto (1916). Introduction to the Pāñcarātra and the Ahirbudhnya saṃhitā. Adyar Library. p. 42.

- ↑ Mishra, Vibhuti Bhushan (1973). Religious beliefs and practices of North India during the early mediaeval period, Volume 1. BRILL. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-90-04-03610-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Nanda, Meera (19 November 2010). "Madame Blavatsky's children: Modern Hinduism's encounters with Darwinism". In James R. Lewis; Olav Hammer. Handbook of Religion and the Authority of Science. BRILL. pp. 279–344. ISBN 90-04-18791-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Brown, C. Mackenzie (June 2007). "The Western roots of Avataric Evolutionism in colonial India". Zygon. 42 (2): 423–448. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9744.2007.00423.x.

- ↑ C. Mackenzie Brown (2012). Hindu Perspectives on Evolution: Darwin, Dharma, and Design. Routledge. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-136-48467-4.

- ↑ Brahmo Samaj, Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ Sen was a leader of the colonial era monotheistic Brahmo Samaj reform movement of Hinduism that adopted ideas from Christianity and Islam.[37]

- ↑ C. Mackenzie Brown (2012). Hindu Perspectives on Evolution: Darwin, Dharma, and Design. Routledge. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-1-136-48467-4.

- 1 2 Nanda, Meera (19 November 2010). "Madame Blavatsky's children: Modern Hinduism's encounters with Darwinism". In James R. Lewis; Olav Hammer. Handbook of Religion and the Authority of Science. BRILL. pp. 279–344. ISBN 90-04-18791-X.

- ↑ Brown, C Mackenzie (19 November 2010). "Vivekananda and the scientific legitimation of Advaita Vedanta". In James R. Lewis; Olav Hammer. Handbook of Religion and the Authority of Science. BRILL. p. 227. ISBN 90-04-18791-X.

- ↑ "Cover Story: Haldane: Life Of A Prodigious Mind". Science Reporter. Council of Scientific & Industrial Research. 29: 46. 1992.

- ↑ Amiya P. Sen (2010). Explorations in Modern Bengal, C. 1800-1900: Essays on Religion, History, and Culture. Primus Books. p. 196. ISBN 978-81-908918-6-8.

- ↑ Chintaman Dwarkanath Deshmukh (1972). Aspects of Development. Young Asia Publication. p. 33.

- ↑ C. Mackenzie Brown (2012). Hindu Perspectives on Evolution: Darwin, Dharma, and Design. Routledge. pp. 182–183. ISBN 978-1-136-48467-4.

Bibliography

- Carman, John Braisted (1994), Majesty and Meekness: A Comparative Study of Contrast and Harmony in the Concept of God, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing

- Holt, John C. (2013), The Buddhist Visnu: Religious Transformation, Politics, and Culture, Columbia University Press

- Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2007). A survey of Hinduism. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-7081-4.

- Krishna, Nanditha (2009), Book of Vishnu, Penguin UK

- Sikand, Yoginder (2004). Muslims in India since 1947: Islamic perspectives on inter-faith relations. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-415-31486-0.

- Sullivan, Bruce M. (2001), The A to Z of Hinduism, Scarecrow Press

- Wuaku, Albert (11 July 2013). Hindu Gods in West Africa: Ghanaian Devotees of Shiva and Krishna. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-25571-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dashavatara. |