Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley

| Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Conquests of Achaemenid Empire | |||||||

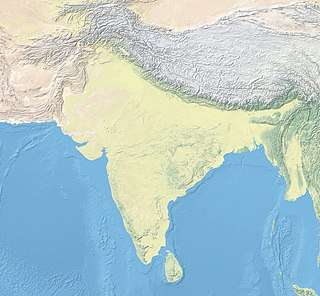

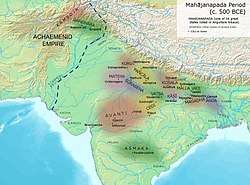

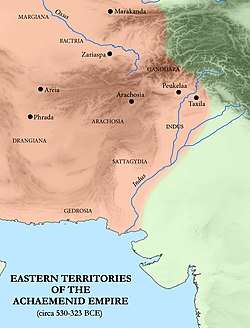

Eastern border of the Achaemenid Empire and ancient kingdoms and cities of ancient India (circa 500 BCE).[1] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Achaemenid Empire | Mahajanapadas | ||||||

The Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley refers to the Achaemenid military conquest and occupation for about two centuries of territories of the North-western regions of the Indian subcontinent. The conquest of the areas as far as the Indus river is often dated to the time of Cyrus the Great, in the period between 550-539 BCE.[1] The first secure epigraphic evidence, given by the Behistun Inscription inscription, gives a date before or about 518 BCE. Achaemenid penetration into the area of the Indian subcontinent occurred in stages, starting from northern parts of the River Indus and moving southward.[3] These areas of the Indus valley became formal Achaemenid satrapies as mentioned in several Achaemenid inscriptions. The Achaemenid occupation of the Indus Valley ended with the Indian campaign of Alexander the Great circa 323 BCE.[1] The Achaemenid occupation, although less successful than that of the later Greeks, Sakas or Kushans, had the effect of acquainting India to the outer world.[4]

Background and invasion

The important communities in the region were the people of Punjab and Sindh and the Kambojas. Punjab consisted of Taksas of Gandhara, the Madras and Kathas (Kathaioi) on Akesines, the Mallas on Hydraotis and the Tugras on Hesidros. In the first half of the sixth century BC, these several small principalities did constitute a powerful state to wield the warring communities into one organized kingdom.[1] The area was wealthy, and could be entered through the passes of the Hindu Kush. The strong Achaemenid dynasty then took an interest into the region.[1]

- Cyrus the Great

The conquest is often thought to have started circa 535 BCE, during the time of Cyrus the Great (600-530 BCE).[5][6][1] He went as far as the banks of the Indus river and organized the conquered territories under the Satrapy of Gandhara. Various accounts, such as those of Xenophon or Ctesias, who wrote Indica, suggest that Cyrus conquered parts of India.[7][1]

- Darius I

A successor of Cyrus the Great, Darius I was back in 518 BCE. The date of 518 BCE is given by the Behistun inscription, and is also often the one given for the secure occupation of Gandhara Kingdom/Takshila in Punjab.[8] Darius I later crossed the Indus river and occupied an area he calls "Hidūš" in his inscriptions (Old Persian cuneiform: 𐏃𐎡𐎯𐎢𐏁, H-i-du-u-š),[9] probably comprising large parts of the Punjab and the modern province of Sind.[10] This new satrapy was exactly called the Satrapy of the Hiduš in his Naqsh-i-Rustam inscription which was written around the end of his reign.[11] The Hamadan Gold and Silver Tablet inscription[12] of Darius I also refers to his conquests in India.[1]

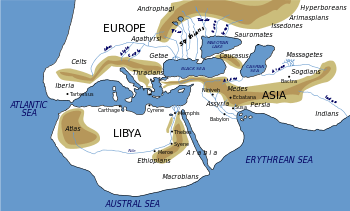

According to Herodotus, Darius I sent the Greek explorer Scylax of Caryanda to sail down the Indus river in order to discover the routes to return to Egypt by the sea. After a periplus of 30 months he is said to have managed to return to Egypt, and the seas between the Near East and India started to be exploited.[13]

The upper Indus region, comprising Gandhara and Kamboja, formed the 7th, Gandhara satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire (including Sattagydians, Dadicae, Aparytae), while the lower and middle Indus, respectively comprising Sindhu and Sauvira, constituted the 20th satrapy (called Indian/Hinduš Satrapy).

- Achaemenid army

The Achaemenid army was not uniquely Persian, and was on the contrary composed of many of the ethnicities that were part of the vast Achaemenid Empire. In the army were included Bactrians, Sakas (Scythians), Parthians, Sogdians.[14] Herodotus gives a full list of the ethinicities of the Achaemenid army, in which are also included Ionians (Greeks), and even Ethiopians.[15][14] These ethnicities must naturally have been included in the Achaemenid army which invaded India.[14]

Inscriptions and accounts

These events were recorded in the imperial inscriptions of the Achaemenids (the Behistun inscription and the Naqsh-i-Rustam inscription), as well as the accounts of Herodotus (483–431 BCE), and of the Hellenistic accounts of the Greek conquests in India (circa 320 BCE). The Greek Scylax of Caryanda, who had been appointed by Darius I to explore the Indian Ocean from the mouth of the Indus to Suez left an account, the Periplous, of which fragments from secondary sources have survived. Hecataeus of Miletus (circa 500 BCE) also wrote about the "Indus Satrapies" of the Achaemenids.

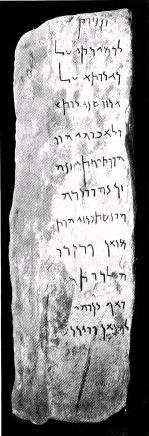

Behistun inscription

The DB Behistun inscription[16] of Darius I (circa 510 BCE) mentions Gandhara (𐎥𐎭𐎠𐎼, Gadâra) and the adjacent territory of Sattagydia (𐎰𐎫𐎦𐎢𐏁, Thataguš) as part of the Achaemenid Empire:

King Darius says: These are the countries which are subject unto me, and by the grace of Ahuramazda I became king of them: Persia [Pârsa], Elam [Ûvja], Babylonia [Bâbiruš], Assyria [Athurâ], Arabia [Arabâya], Egypt [Mudrâya], the countries by the Sea, Lydia [Sparda], the Greeks [Yauna (Ionia)], Media [Mâda], Armenia [Armina], Cappadocia [Katpatuka], Parthia [Parthava], Drangiana [Zraka], Aria [Haraiva], Chorasmia [Uvârazmîy], Bactria [Bâxtriš], Sogdia [Suguda], Gandhara [Gadâra], Scythia [Saka], Sattagydia [Thataguš], Arachosia [Harauvatiš] and Maka [Maka]; twenty-three lands in all.

From the dating of the Behistun inscription, it is possible to infer that the Achaemenids first conquered the areas of Gandhara and Sattagydia circa 518 BCE.

Naqsh-e Rustam inscription

The DSe inscription[19] and DSm inscription[20] of Darius in Susa gives Thataguš (Sattagydia), Gadâra (Gandhara) and Hiduš (Sindh) among the nations that he rules.[19][21]

Hidūš (𐏃𐎡𐎯𐎢𐏁 in Old Persian cuneiform) also appears later as a Satrapy in the Naqsh-i-Rustam inscription at the end of the reign of Darius, who died in 486 BCE.[22] The DNa inscription[23] on Darius' tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam near Persepolis records Gadâra (Gandhāra) along with Hiduš and Thataguš (Sattagydia) in the list of satrapies.[24]

King Darius says: By the favor of Ahuramazda these are the countries which I seized outside of Persia; I ruled over them; they bore tribute to me; they did what was said to them by me; they held my law firmly; Media, Elam, Parthia, Aria, Bactria, Sogdia, Chorasmia, Drangiana, Arachosia, Sattagydia, Gandara (Gadâra), India (Hiduš), the haoma-drinking Scythians, the Scythians with pointed caps, Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, Armenia, Cappadocia, Lydia, the Greeks (Yauna), the Scythians across the sea (Sakâ), Thrace, the petasos-wearing Greeks [Yaunâ], the Libyans, the Nubians, the men of Maka and the Carians.

Statue of Darius inscriptions

Hinduš is also mentioned as one of 24 subject countries of the Achaemenid Empire, illustrated with the drawing of a kneeling subject and a hieroglyphic cartridge reading 𓉔𓈖𓂧𓍯𓇌 (H-n-d-wꜣ-y, Hinduš), on the Egyptian Statue of Darius I, now in the National Museum of Iran. Sattagydia also appears (𓐠𓂧𓎼𓍯𓍒, S-d-g-wꜣ-ḏꜣ, Sattagydia), and probably Gandhara (𓉔𓃭𓐍𓂧𓇌, H-rw-h-d-y) as well, with their own illustrations.[27][28]

Achaemenid administration

_Gandhara.jpg)

The conquered area was the most fertile and populous region of the Achaemenid Empire. The Indus Valley was already fabled for its gold; the province was able to supply gold dust equal in value to the very large amount of 4680 silver talents. Under Persian rule, a system of centralized administration with a bureaucratic system was introduced in the region and scholars such as Pāṇini and Kautilya lived in an Achaemenid environment.[29][30][31] A certain number of Indians were recruited to the Persian army at that time, and Achaemenid ruler Xerxes I employed them in his wars against the Greeks.[32]

- List of Provinces.

According to the Achaemenid inscriptions, several provinces are listed separately, which correspond to the easternmost Achaemenid provinces: Thataguš (Sattagydia), Gadâra (Gandhara) and Hidūš (Sindh).[33]

Herodotus (III-91 and III-94), gives a slightly different list when describing the tribute paid by each territory.[34][35] He presents Hinduš (Ἰνδός, Indos) as "the 20th province", while "the Sattagydae, Gandarii, Dadicae, and Aparytae" together form "the 7th Province".[36]

- Later accounts

Circa 400 BC, Ctesias of Cnidus still related that the Persian king was receiving numerous gifts from Indian provinces, attesting to the probable continuous presence of the Achaemenids in India.[37]

The Indians also include this substance among their most precious gifts for the Persian king who receives it as a prize revered above all others.

— Ctesias of Cnidus, in Aelian. N.A. 4.41[38]

According to Aelian, Ctesias of Cnidus also reports about Indian elephants and Indian mahouts making demonstrations of the elephant's strength at the Achaemenid court.[39]

By about 380 BC, the Persian hold on the region was weakening, but the area continued to be a part of the Achaemenid Empire until Alexander's invasion.[40]

Darius III (c. 380 – July 330 BC) still had Indian units in his army.[37] In particular he had 15 war elephants at Gaugamela for his battle against Alexander the Great.[41]

Indian tributes

Apadana Palace

The reliefs at the Apadana Palace in Persepolis describe tribute bearers from 23 satrapies visiting the Achaemenid court. These are located at the southern end of the Apadana Staircase. Among the foreigners the Arabs, the Thracians, the Bactrians, the Indians (from the Indus valley area), the Parthians, the Cappadocians, the Elamites or the Medians. The Indians from the Indus valley are bare-chested, except for their leader, and barefooted and wear the dhoti. They bring baskets with vases inside, carry axes, and drive along a donkey.[42]

According to the Naqsh-e Rustam inscription of Darius I (circa 490 BCE), there were three Achaemenid Satrapies in in the subcontinent: Sattagydia, Gandara (Gadâra), Sindh (Hidūš)[43][44] One of the Achaemenid cities was near Taxila at Bhir Mound, now an archaeological site. The site of Bhir Mound clearly attests of the Achaemenid expansion in the area.[45]

Tribute payments

._Period_of_Achaemenid_Rule._Circa_5th_century_BCE.jpg)

Herodotus (who makes several comments on India) published a list of tribute-paying nations, classifying them in 20 Provinces, each headed by an Achaemenid governor.[48][35] The Province of Hinduš (Ἰνδός, Indos) formed the 20th Province, and was the richest and most populous of the Achaemenid Provinces, paying about 1/3 of all the tributes, an annual amount of 360 talents of gold dust (whereas the other Provinces paid in silver), or 4680 Euboean talents (about 10 tons).[49]

The Indians ( Ἰνδῶν) made up the twentieth province. These are more in number than any nation known to me, and they paid a greater tribute than any other province, namely three hundred and sixty talents of gold dust.

The territories of Gandhara, Sattagydia, Dadicae (northwest of the Kashmir valley) and the Aparytae (Afridis) are named separately, forming the 7th Achaemenid Province, and paying a much lower tribute of 170 talents together (about 5 tons of silver annually):

The Sattagydae (Σατταγύδαι), Gandarii (Γανδάριοι), Dadicae (Γανδάριοι), and Aparytae (Ἀπαρύται) paid together a hundred and seventy talents; this was the seventh province

The Indians also supplied Yaka wood (teak) for the construction of Achaemenid palaces,[50][44] as well as war elephants such as those used at Gaugamela.[44] The Susa inscriptions of Darius explain that Indian ivory and teak were sold on Persian markets, and used in the construction of his palace.[1]

Contribution to Achaemenid war efforts

Indians were employed in the Achaemenid army of Xerxes in the Second Persian invasion of Greece (480-479 BCE), and Herodotus described their equipment:[51]

The Indians wore garments of tree-wool, and carried bows of reed and iron-tipped arrows of the same. Such was their equipment; they were appointed to march under the command of Pharnazathres son of Artabates.

— Herodotus VII 65

Herodotus also explains that the Indian cavalry under the Achaemenids had an equipment similar that of their foot soldiers:

The Indians were armed in like manner as their foot; they rode swift horses and drove chariots drawn by horses and wild asses.

— Herodotus VII 86

The Gandharis had a different equipment, akin to that of the Bactrians:

The Bactrians in the army wore a headgear most like to the Median, carrying their native bows of reed, and short spears. (...) The Parthians, Chorasmians, Sogdians, Gandarians, and Dadicae in the army had the same equipment as the Bactrians. The Parthians and Chorasmians had for their commander Artabazus son of Pharnaces, the Sogdians Azanes son of Artaeus, the Gandarians and Dadicae Artyphius son of Artabanus.

— Herodotus VII 64-66

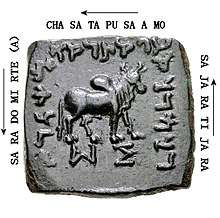

Greek and Achaemenid coinage

Coin finds in the Chaman Hazouri hoard in Kabul or the Shaikhan Dehri hoard in Pushkalavati, the ancient capital of the Gandhara Satrapy near Charsadda, have revealed numerous Achaemenid coins as well as many Greek coins from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE which circulated in the area, at least as far as the Indus during the reign of the Achaemenids, who were in control of the areas as far as Gandhara.[54][55][52][45]

Kabul hoard

The Kabul hoard, also called the Chaman Hazouri, Chaman Hazouri or Tchamani-i Hazouri hoard,[54] is a coin hoard discovered in the vicinity of Kabul, Afghanistan. The hoard, discovered in 1933, contained numerous Achaemenid coins as well as many Greek coins from the 5th and 4th centuries BCE.[52] Approximately one thousand coins were counted in the hoard.[54][56] The hoard is dated to approximately 380 BCE as no coins of the hoard were beyond that date.[57] This numismatic discovery has been very important in studying and dating the history of the coinage of India, since it is one of the very rare instances when punch-marked coins can actually be dated, due to their association with known and dated Greek and Achaemenid coins in the hoard.[58] The hoard proves that punch-marked coins existed in 360 BCE, as also suggested by literary evidence.[58]

Daniel Schlumberger also considers that punch-marked bars, similar to the many punch-marked bars found in northwestern India, initially originated in the Achaemenid Empire, rather than in the Indian heartland:

“The punch-marked bars were up to now considered to be Indian (...) However the weight standard is considered by some expert to be Persian, and now that we see them also being uncovered in the soil of Afghanistan, we must take into account the possibility that their country of origin should not be sought beyond the Indus, but rather in the oriental provinces of the Achaemenid Empire"

Numismat Osmund Bopearachchi confirms that "the local coins of the Achaemenid era (...) were the precursors of the bent and punch-marked bars".[59]

Pushkalavati hoard

In 2007 a small coin hoard was discovered at the site of ancient Pushkalavati (Shaikhan Dehri) near Charsada in Pakistan. The hoard contained a tetradrachm minted in Athens circa 500/490-485/0 BCE, together with a number of local types as well as silver cast ingots. The hoard contained a tetradrachm minted in Athens circa 500/490-485/0 BCE, typically used as a currency for trade in the Achaemenid Empire, together with a number of local types as well as silver cast ingots. The Athens coin is the earliest known example of its type to be found so far to the east.[61][62]

According to Joe Cribb, these early Greek coins were at the origin of Indian punch-marked coins, the earliest coins developed in India, which used minting technology derived from Greek coinage.[52]

Influence of Achaemenid culture in India

Taxila

Taxila, the capital of Achaemenid rule in northwestern India and at the crossroad of the main trade roads of Asia, was probably populated by Persians, Greeks and other people from throughout the Achaemenid Empire.[63][64][65] The renowned University of Taxila became the greatest learning center in the region, and allowed for exchanges between people from various cultures.[66]

- Followers of the Buddha

Several contemporaries, and close followers, of the Buddha are said to have studied in Achaemenid Taxila: King Pasenadi of Kosala, a close friend of the Buddha, Bandhula, the commander of Pasedani's army, Aṅgulimāla, a close follower of the Buddha, and Jivaka, court doctor at Rajagriha and personal doctor of the Buddha.[67] According to Stephen Batchelor, the Buddha may have been influenced by the experiences and knowledge acquired by some of his closest followers in Taxila.[68]

- Pāṇini

The great 5th century BCE grammarian Pāṇini is said to have been born in the northwest, in Shalatula near Attock, not far from Taxila, in what was then a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, which technically made him in all probability a Persian subject.[69][70][71]

- Kautilya

Kautilya, the influential Prime Minister of Chandragupta Maurya is also said to have been a professor teaching in Taxila.[72]

Pataliputra

Various Indian artifacts tend to suggest some Perso-Hellenistic artistic influence in India, mainly felt during the time of the Mauryan Empire.[1] The sculpture of the Masarh lion, found near the Maurya capital of Pataliputra, raises the question of the Achaemenid and Greek influence on the art of the Maurya Empire, and on the western origins of stone carving in India. The lion is carved in Chunar sandstone, like the Pillars of Ashoka, and its finish is polished, a feature of the Maurya sculpture.[73] According to S.P. Gupta, the sculptural style is unquestionably Achaemenid.[73] This is particularly the case for the well-ordered tubular representation of whiskers (vibrissas) and the geometrical representation of inflated veins flush with the entire face.[73] The mane, on the other hand, with tufts of hair represented in wavelets, is rather naturalistic.[73] Very similar examples are however known in Greece and Persepolis.[73] It is possible that this sculpture was made by an Achaemenid or Greek sculptor in India and either remained without effect, or was the Indian imitation of a Greek or Achaemenid model, somewhere between the fifth century B.C. and the first century B.C., although it is generally dated from the time of the Maurya Empire, around the 3rd century B.C..[73]

The Pataliputra palace with its pillared hall shows decorative influences of the Achaemenid palaces and Persepolis and may have used the help of foreign craftmen.[74][1] Mauryan rulers may have even imported craftsmen from abroad to build royal monuments.[75] This may be the result of the formative influence of craftsmen employed from Persia following the disintegration of the Achaemenid Empire after the conquests of Alexander the Great.[76][77] The Pataliputra capital, or also the Hellenistic friezes of the Rampurva capitals, Sankissa, and the diamond throne of Bodh Gaya are other examples.[78].

The renowned Mauryan polish, especially used in the Pillars of Ashoka, may also have been a technique imported from the Achaemenid Empire.[1]

Ruins of pillared hall at Kumrahar site at Pataliputra.

Ruins of pillared hall at Kumrahar site at Pataliputra. Plan of the 80-column pillared hall in Pataliputra.

Plan of the 80-column pillared hall in Pataliputra.

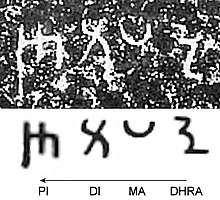

Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka (circa 250 BCE) may show Achaemenid influences, including formulaic parallels with Achaemenid inscriptions, presence of Iranian loanwords (in Aramaic inscriptions), and the very act of engraving edicts on rocks and mountains (compare for example Behistun inscription).[80][81] To describe his own edicts, Ashoka used the word Lipī (𑀮𑀺𑀧𑀺), now generally simply translated as "writing" or "inscription". It is thought the word "lipi", which is also orthographed "dipi" (𐨡𐨁𐨤𐨁) in the two Kharosthi versions of the rock edicts,[note 1] comes from an Old Persian prototype dipî (𐎮𐎡𐎱𐎡) also meaning "inscription", which is used for example by Darius I in his Behistun inscription,[note 2] suggesting borrowing and diffusion.[82][83][84] There are other borrowings of Old Persian terms for writing-related words in the Edicts of Ahoka, such as nipista or nipesita ("written" and "made to be written") in the Kharoshthi version of Major Rock Edict No.4, which can be related to the word nipištā ("written") from the daiva inscription of Xerxes at Persepolis.[85]

Aramaic language and script

The Aramaic language, official language of the Achaemenid Empire, started to be used in the Indian territories.[86] Some of the Edicts of Ashoka in the northwestern areas of Ashoka's territory, in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan, used Aramaic (the official language of the former Achaemenid Empire), together with Prakrit and Greek (the language of the neighbouring Greco-Bactrian kingdom and the Greek communities in Ashoka's realm).[87]

The Indian Kharosthi script shows a clear dependency on the Aramaic alphabet but with extensive modifications to support the sounds found in Indic languages.[1] One model is that the Aramaic script arrived with the Achaemenid Empire's conquest of the Indus River (modern Pakistan) in 500 BCE and evolved over the next 200+ years, reaching its final form by the 3rd century BCE where it appears in some of the Edicts of Ashoka.[86][1]

Frieze of Sankissa.

Frieze of Sankissa. Frieze of the diamond throne of Bodh Gaya.

Frieze of the diamond throne of Bodh Gaya. The word Dipi ("Edict") in the Edicts of Ashoka, identical with the Achaemenid word for "writing".[88]

The word Dipi ("Edict") in the Edicts of Ashoka, identical with the Achaemenid word for "writing".[88] The Kharoshthi script is generally considered as a development from Aramaic.

The Kharoshthi script is generally considered as a development from Aramaic.

Religion

Historically, the life of the Buddha also coincided with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley.[89] The Achaemenid occupation of the areas of Gandhara and Sindh, which was to last for about two centuries, was accompanied by the introduction of Achaemenid religions, reformed Mazdaism or early Zoroastrianism, to which Buddhism might have in part reacted.[89] In particular, the ideas of the Buddha may have partly consisted in a rejection of the "absolutist" or "perfectionist" ideas contained in these Achaemenid religions.[89]

Still, according to Christopher I. Beckwith, commenting on the content of the Edicts of Ashoka, the early Buddhist concepts of karma, rebirth, and affirming that good deeds with be rewarded in this life and the next, in Heaven, probably find their origin in Achaemenid Mazdaism, which had been introduced in India from the time of the Achaemenid conquest of Gandhara.[90]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 116–117. ISBN 9788122411980.

- ↑ Errington, Elizabeth; Trust, Ancient India and Iran; Museum, Fitzwilliam (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ancient India and Iran Trust. p. 56. ISBN 9780951839911.

- ↑ (Fussman, 1993, p. 84). "This is inferred from the fact that Gandhara (OPers. Gandāra) is already mentioned at Bisotun, while the toponym Hinduš (Sind) is added only in later inscriptions."

- ↑ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 118. ISBN 9788122411980.

- ↑ Kerr, Gordon (2017). A Short History of India: From the Earliest Civilisations to Today's Economic Powerhouse (in German). Oldcastle Books. p. PT16. ISBN 9781843449232.

- ↑ Thapar, Romila (1990). A History of India. Penguin UK. p. 422. ISBN 9780141949765.

- ↑ Tauqeer Ahmad, University of the Punjab, Lahore, South Asian Studies, A Research Journal of South Asian Studies, Vol. 27, No. 1, January-June 2012, pp. 221-232 p.222

- ↑ Marshall, John (1975) [1951]. Taxila: Volume I. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 83.

- ↑ DNa - Livius.

- ↑ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 117. ISBN 9788122411980.

- ↑ "DNa - Livius". www.livius.org.

- ↑ Hamadan Gold and Silver Tablet inscription

- ↑ Parker, Grant (2008). The Making of Roman India. Cambridge University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780521858342.

- 1 2 3 Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9781400866328.

- ↑ Herodotus VII 65

- ↑ Behistun T 02 - Livius.

- ↑ King, L. W. (Leonard William); Thompson, R. Campbell (Reginald Campbell) (1907). The sculptures and inscription of Darius the Great on the Rock of Behistûn in Persia : a new collation of the Persian, Susian and Babylonian texts. London : Longmans. p. 3.

- ↑ Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. p. 21. ISBN 9788172110284.

- 1 2 DSe - Livius.

- ↑ DSm inscription

- ↑ Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. p. 21. ISBN 9788172110284.

- ↑ "INDIA RELATIONS: ACHAEMENID PERIOD – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- ↑ DNa - Livius.

- ↑ Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. p. 20. ISBN 9788172110284.

- ↑ "DNa - Livius". www.livius.org.

- ↑ Alcock, Susan E.; Alcock, John H. D'Arms Collegiate Professor of Classical Archaeology and Classics and Arthur F. Thurnau Professor Susan E.; D'Altroy, Terence N.; Morrison, Kathleen D.; Sinopoli, Carla M. (2001). Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History. Cambridge University Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780521770200.

- ↑ "Susa, Statue of Darius - Livius". www.livius.org.

- ↑ Yar-Shater, Ehsan (1982). Encyclopaedia Iranica. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 10. ISBN 9780933273955.

- ↑ Scharfe, Hartmut (1977). Grammatical Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 89. ISBN 9783447017060.

- ↑ Bakshi, S. R. (2005). Early Aryans to Swaraj. Sarup & Sons. p. 47. ISBN 9788176255370.

- ↑ Ninan, M. M. (2008). The Development of Hinduism. Madathil Mammen Ninan. p. 97. ISBN 9781438228204.

- ↑ Chandra, Lokesh (1986), "The cultural symphony of India and Greece", in R. Balsubramanian; S. Bhattacharyya, Freedom, Progress, and Society: Essays in Honour of Professor K. Satchidananda Murty, Motilal Banarsidass Publishe, pp. 89–102, ISBN 978-81-208-0262-9

- ↑ Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. p. 21. ISBN 9788172110284.

- ↑ Herodotus III 91 [[]], Herodotus III 94

- 1 2 3 4 Mitchiner, Michael (1978). The ancient & classical world, 600 B.C.-A.D. 650. Hawkins Publications ; distributed by B. A. Seaby. p. 44. ISBN 9780904173161.

- ↑ Mitchiner, Michael (1978). The ancient & classical world, 600 B.C.-A.D. 650. Hawkins Publications ; distributed by B. A. Seaby. p. 44. ISBN 9780904173161.

- 1 2 "INDIA RELATIONS: ACHAEMENID PERIOD – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- ↑ The Complete Fragments of Ctesias of Cnidus. pp. 120–121.

- ↑ The Complete Fragments of Ctesias of Cnidus. p. Page 116 Fragment F45bα) and Page 219 Note F45bα).

- ↑ The hypothesis that the region had already become independent by the end of the reign of Darius I or during the reign of Artaxerxes II (Chattopadhyaya, 1974, pp. 25-26) appears to be contradicted by Ctesias’s reference to gifts received from the kings of India and by the fact that even Darius III still had some Indian units in his army (Briant, 1996, pp. 699, 774). At the time of the arrival of the Alexander's Macedonian army in the Indus Valley, there is no mention of officers of the Persian kings in India; but this does not mean (Dittmann, 1984, p. 185) that the Achaemenids had no power there. Other data indicate that they still exercised control over the area, although in ways that differed from those of Darius I’s time (Briant, 1996, pp. 776-78).

- ↑ Kistler, John M. (2007). War Elephants. U of Nebraska Press. p. 29. ISBN 0803260040.

- ↑ André-Salvini, Béatrice (2005). Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520247314.

- ↑ "DNa - Livius". www.livius.org.

- 1 2 3 Bosworth, A. B. (1996). Alexander and the East : The Tragedy of Triumph: The Tragedy of Triumph. Clarendon Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780191589454.

- 1 2 3 Bopearachchi, Osmund. “Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander’s Conquest)”. pp. 308-.

- ↑ CNG Coins

- ↑ CNG Coins

- ↑ Herodotus III, 89

- ↑ Archibald, Zosia; Davies, John K.; Gabrielsen, Vincent (2011). The Economies of Hellenistic Societies, Third to First Centuries BC. Oxford University Press. p. 404. ISBN 9780199587926.

- ↑ DSf inscription

- ↑ Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9781400866328.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Errington, Elizabeth; Trust, Ancient India and Iran; Museum, Fitzwilliam (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ancient India and Iran Trust. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9780951839911.

- ↑ CNG Coins

- 1 2 3 Bopearachchi, Osmund. “Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander’s Conquest)”. pp. 300–301.

- ↑ US Department of Defense

- ↑ US Department of Defense

- ↑ Bopearachchi, Osmund. “Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander’s Conquest)”. p. 308.

- 1 2 Cribb, Joe. Investigating the introduction of coinage in India- a review of recent research, Journal of the Numismatic Society of India XLV (Varanasi 1983), pp.80-101. pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Bopearachchi, Osmund. “Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander’s Conquest)”. p. 311.

- ↑ O. Bopearachchi, “Premières frappes locales de l’Inde du Nord-Ouest: nouvelles données,” in Trésors d’Orient: Mélanges offerts à Rika Gyselen, Fig. 1 CNG Coins

- ↑ O. Bopearachchi, “Premières frappes locales de l’Inde du Nord-Ouest: nouvelles données,” in Trésors d’Orient: Mélanges offerts à Rika Gyselen, Fig. 1 (this coin) CNG Coins

- ↑ Bopearachchi, Osmund. “Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander’s Conquest)”. p. 309.

- ↑ Lowe, Roy; Yasuhara, Yoshihito (2016). The Origins of Higher Learning: Knowledge networks and the early development of universities. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 9781317543268.

- ↑ Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 50. ISBN 9780984404308.

- ↑ Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 255-256. ISBN 9781588369840.

- ↑ Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 125. ISBN 9781588369840.

- ↑ Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 256. ISBN 9781588369840.

- ↑ Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 255. ISBN 9781588369840.

- ↑ Scharfe, Hartmut (1977). Grammatical Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 89. ISBN 9783447017060.

- ↑ Bakshi, S. R. (2005). Early Aryans to Swaraj. Sarup & Sons. p. 47. ISBN 9788176255370.

- ↑ Ninan, M. M. (2008). The Development of Hinduism. Madathil Mammen Ninan. p. 97. ISBN 9781438228204.

- ↑ Schlichtmann, Klaus (2016). A Peace History of India: From Ashoka Maurya to Mahatma Gandhi. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. p. 29. ISBN 9789385563522.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The roots of Indian Art, Gupta, p. 88

- ↑ The Analysis of Indian Muria Empire affected from Achaemenid’s architecture art Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine.. In: Journal of Subcontinent Researches. Article 8, Volume 6, Issue 19, Summer 2014, Page 149-174.

- ↑ Monuments, Power and Poverty in India: From Ashoka to the Raj, A. S. Bhalla, I.B.Tauris, 2015 p.18

- ↑ "The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE-200 CE" Robin Coningham, Ruth Young Cambridge University Press, 31 aout 2015, p.414

- ↑ Report on the excavations at Pātaliputra (Patna); the Palibothra of the Greeks by Waddell, L. A. (Laurence Austine)

- ↑ The Origins of Indian Stone Architecture, 1998, John Boardman p. 13-22.

- ↑ "A griffin carved from milky white chalcedony represents a blend of Greek and Achaemenid Persian cultures", National Geographic, Volume 177, National Geographic Society, 1990

- ↑ Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. p. 39. ISBN 9788172110284.

- ↑ "Ashoka" in Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ Hultzsch, E. (1925). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum v. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. xlii.

- ↑ Sharma, R. S. (2006). India's Ancient Past. Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780199087860.

- ↑ "The word dipi appears in the Old Persian inscription of Darius I at Behistan (Column IV. 39) having the meaning inscription or "written document" in Congress, Indian History (2007). Proceedings - Indian History Congress. p. 90.

- ↑ Voogt, Alexander J. de; Finkel, Irving L. (2010). The Idea of Writing: Play and Complexity. BRILL. p. 209. ISBN 900417446X.

- 1 2 Marshall, John (2013). A Guide to Taxila. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9781107615441.

- ↑ Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 73–76. ISBN 9780195356663.

- ↑ Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 51.

- 1 2 3 Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 7-12. ISBN 9781400866328.

- ↑ Beckwith, Christopher I. (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 132-133. ISBN 9781400866328.

Notes

- ↑ For example, according to Hultzsch, the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi (or at Mansehra) reads: "(Ayam) Dhrama-dipi Devanapriyasa Raño likhapitu" ("This Dharma-Edicts was written by King Devanampriya" Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 51.

This appears in the reading of Hultzsch's original rubbing of the Kharoshthi inscription of the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi. - ↑ For example Column IV, Line 89

External links

- Ancient India, A History Textbook for Class XI, Ram Sharan Sharma, National Council of Educational Research and Training, India Iranian and Macedonian Invasion, pp 108

- INDIA iii. RELATIONS: ACHAEMENID PERIOD