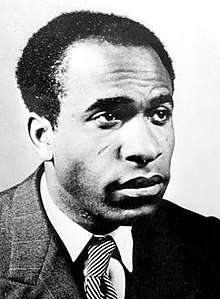

Frantz Fanon

| Frantz Fanon | |

|---|---|

Frantz Fanon | |

| Born |

Frantz Fanon 20 July 1925 Fort-de-France, Martinique, France |

| Died |

6 December 1961 (aged 36) Bethesda, Maryland, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Lyon |

| Notable work | Black Skin, White Masks, The Wretched of the Earth |

| Spouse(s) | Josie Fanon |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Africana philosophy |

| School |

Marxism Black existentialism Critical theory |

Main interests | Decolonization and Postcolonialism, revolution, psychopathology of colonization |

Notable ideas | Double consciousness, colonial alienation, To become black |

Frantz Fanon (/fəˈnɔːn/; French: [fʁɑ̃ts fanɔ̃]; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a psychiatrist, philosopher, revolutionary, and writer from the French colony of Martinique, whose works are influential in the fields of post-colonial studies, critical theory, and Marxism.[1] As an intellectual, Fanon was a political radical, Pan-Africanist, and Marxist humanist concerned with the psychopathology of colonization,[2] and the human, social, and cultural consequences of decolonization.[3][4][5]

In the course of his work as a physician and psychiatrist, Fanon supported the Algerian War of Independence from France, and was a member of the Algerian National Liberation Front. For more than five decades, the life and works of Frantz Fanon have inspired national liberation movements and other radical political organizations in Palestine, Sri Lanka, South Africa, and the United States.[6][7][8] In What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction To His Life And Thought, leading African scholar and contemporary philosopher Lewis R. Gordon remarked that

Fanon's contributions to the history of ideas are manifold. He is influential not only because of the originality of his thought but also because of the astuteness of his criticisms. He developed a profound social existential analysis of antiblack racism, which led him to identify conditions of skewed rationality and reason in contemporary discourses on the human being.[9]

Fanon published numerous books, including The Wretched of the Earth (1961). This influential work focuses on what he believes is the necessary role of violence by activists in conducting decolonization struggles.

Biography

Early life

Frantz Fanon was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique, which was then a French colony and is now a French département. His father, Félix Casimir Fanon, was a descendant of African slaves and indentured Indians and worked as a customs agent. His mother, Eléanore Médélice, was of black Martinician and white Alsatian descent and worked as a shopkeeper.[10] Fanon was the youngest of four sons in a family of eight children, two of whom died in childhood. Fanon's family was socio-economically middle-class. They could afford the fees for the Lycée Schoelcher, then the most prestigious high school in Martinique, where Fanon had the writer Aimé Césaire as one of his teachers.[11] Fanon left Martinique in 1943 when he was 18 years old in order to join the Free French forces.[12]

Martinique and World War II

After France fell to the Nazis in 1940, Vichy French naval troops were blockaded on Martinique. Forced to remain on the island, French sailors took over the government from the Martiniquan people and established a collaborationist Vichy regime. In the face of economic distress and isolation under the blockade, they instituted an oppressive regime; Fanon described them as taking off their masks and behaving like "authentic racists."[13] Residents made many complaints of harassment and sexual misconduct by the sailors. The abuse of the Martiniquan people by the French Navy influenced Fanon, reinforcing his feelings of alienation and his disgust with colonial racism. At the age of seventeen, Fanon fled the island as a "dissident" (a term used for Frenchmen joining Gaullist forces), traveling to British-controlled Dominica to join the Free French Forces.

He enlisted in the Free French army and joined an Allied convoy that reached Casablanca. He was later transferred to an army base at Béjaïa on the Kabylie coast of Algeria. Fanon left Algeria from Oran and served in France, notably in the battles of Alsace. In 1944 he was wounded at Colmar and received the Croix de guerre. When the Nazis were defeated and Allied forces crossed the Rhine into Germany along with photo journalists, Fanon's regiment was "bleached" of all non-white soldiers. Fanon and his fellow Afro-Caribbean soldiers were sent to Toulon (Provence).[7] Later, they were transferred to Normandy to await repatriation.

During the war, Fanon was exposed to severe European anti-black racism. For example, white women liberated by black soldiers often preferred to dance with fascist Italian prisoners, rather than fraternize with their liberators.[10]

In 1945, Fanon returned to Martinique. He lasted a short time there. He worked for the parliamentary campaign of his friend and mentor Aimé Césaire, who would be a major influence in his life. Césaire ran on the communist ticket as a parliamentary delegate from Martinique to the first National Assembly of the Fourth Republic. Fanon stayed long enough to complete his baccalaureate and then went to France, where he studied medicine and psychiatry.

Fanon was educated in Lyon, where he also studied literature, drama and philosophy, sometimes attending Merleau-Ponty's lectures. During this period, he wrote three plays, of which two survive.[14] After qualifying as a psychiatrist in 1951, Fanon did a residency in psychiatry at Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole under the radical Catalan psychiatrist François Tosquelles. He invigorated Fanon's thinking by emphasizing the role of culture in psychopathology.

After his residency, Fanon practised psychiatry at Pontorson, near Mont Saint-Michel, for another year and then (from 1953) in Algeria. He was chef de service at the Blida–Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria. He worked there until being deported in January 1957.[15]

France

In France while completing his residency, Fanon wrote and published his first book, Black Skin, White Masks (1952), an analysis of the negative psychological effects of colonial subjugation upon black people. Originally, the manuscript was the doctoral dissertation, submitted at Lyon, entitled "Essay on the Disalienation of the Black", which was a response to the racism that Fanon received while studying psychiatry and medicine at university in Lyon; the rejection of the dissertation prompted Fanon to publish it as a book. For his doctor of philosophy degree, he submitted another dissertation of narrower scope and different subject. Left-wing philosopher Francis Jeanson, leader of the pro-Algerian independence Jeanson network, read Fanon's manuscript and insisted upon the new title; he also wrote the epilogue. Jeanson was a senior book editor at Éditions du Seuil, in Paris.[16]

When Fanon submitted the manuscript of Black Skin, White Masks (1952) to Seuil, Jeanson invited him for an editor–author meeting; he said it did not go well as Fanon was nervous and over-sensitive. Despite Jeanson praising the manuscript, Fanon abruptly interrupted him, and asked: "Not bad for a nigger, is it?" Jeanson was insulted, became angry, and dismissed Fanon from his editorial office. Later, Jeanson said he learned that his response to Fanon's discourtesy earned him the writer's lifelong respect. Afterward, their working and personal relationships became much easier. Fanon agreed to Jeanson's suggested title, Black Skin, White Masks.[16]

Algeria

Fanon left France for Algeria, where he had been stationed for some time during the war. He secured an appointment as a psychiatrist at Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in 1953. He radicalized his methods of treatment, particularly beginning socio-therapy to connect with his patients' cultural backgrounds. He also trained nurses and interns. Following the outbreak of the Algerian revolution in November 1954, Fanon joined the Front de Libération Nationale, after having made contact with Dr Pierre Chaulet at Blida in 1955. Working at a French hospital in Algeria, Fanon became responsible for treating the psychological distress of the French soldiers and officers who carried out torture in order to suppress anti-colonial resistance. Additionally, Fanon was also responsible for treating Algerian torture victims. Fanon then realized that he could no longer continue to support French efforts, so he resigned from his position at the hospital in 1956. After discontinuing his work at the French hospital, Fanon was able to devote more of his time to aiding Algeria in its fight for Independence.[17]

In The Wretched of the Earth (1961, Les damnés de la terre), published shortly before Fanon's death, the writer defends the right of a colonized people to use violence to gain independence. In addition, he delineated the processes and forces leading to national independence or neocolonialism during the decolonization movement that engulfed much of the world after World War II. In defence of the use of violence by colonized peoples, Fanon argued that human beings who are not considered as such (by the colonizer) shall not be bound by principles that apply to humanity in their attitude towards the colonizer. His book was censored by the French government.

Fanon made extensive trips across Algeria, mainly in the Kabyle region, to study the cultural and psychological life of Algerians. His lost study of "The marabout of Si Slimane" is an example. These trips were also a means for clandestine activities, notably in his visits to the ski resort of Chrea which hid an FLN base. By summer 1956 he wrote his "Letter of resignation to the Resident Minister" and made a clean break with his French assimilationist upbringing and education. He was expelled from Algeria in January 1957, and the "nest of fellaghas [rebels]" at Blida hospital was dismantled.

Fanon left for France and travelled secretly to Tunis. He was part of the editorial collective of El Moudjahid, for which he wrote until the end of his life. He also served as Ambassador to Ghana for the Provisional Algerian Government (GPRA). He attended conferences in Accra, Conakry, Addis Ababa, Leopoldville, Cairo and Tripoli. Many of his shorter writings from this period were collected posthumously in the book Toward the African Revolution. In this book Fanon reveals war tactical strategies; in one chapter he discusses how to open a southern front to the war and how to run the supply lines.[15]

Death

Upon his return to Tunis, after his exhausting trip across the Sahara to open a Third Front, Fanon was diagnosed with leukemia. He went to the Soviet Union for treatment and experienced some remission of his illness. When he came back to Tunis once again, he dictated his testament The Wretched of the Earth. When he was not confined to his bed, he delivered lectures to Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN) officers at Ghardimao on the Algero-Tunisian border. He made a final visit to Sartre in Rome. In 1961, the CIA arranged a trip to the U.S. for further leukemia treatment at a National Institutes of Health facility.[18]

Fanon died in Bethesda, Maryland, on 6 December 1961, under the name of "Ibrahim Fanon", a Libyan nom de guerre that he had assumed in order to enter a hospital in Rome after being wounded in Morocco during a mission for the Algerian National Liberation Front.[19] He was buried in Algeria after lying in state in Tunisia. Later, his body was moved to a martyrs' (chouhada) graveyard at Ain Kerma in eastern Algeria. Frantz Fanon was survived by his French wife Josie (née Dublé), their son Olivier Fanon, and his daughter from a previous relationship, Mireille Fanon-Mendès France. Josie committed suicide in Algiers in 1989.[15] Mireille became a professor at Paris Descartes University and a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, in international law and conflict resolution. She has also worked for UNESCO and the French National Assembly, and serves as president of the Frantz Fanon Foundation. Olivier worked through to his retirement as an official at the Algerian Embassy in Paris. He became president of the Frantz-Fanon National Association which was created in Algiers in 2012.[20] His wife, Valérie Fanon-Raspail, manages the Fanon website.

Work

Black Skin, White Masks is one of Fanon's important works. In Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon psychoanalyzes the oppressed Black person who is perceived to have to be a lesser creature in the White world that they live in, and studies how they navigate the world through a performance of White-ness.[10] Particularly in discussing language, he talks about how the black person's use of a colonizer's language is seen by the colonizer as predatory, and not transformative, which in turn may create insecurity in the black's consciousness.[21] He recounts that he himself faced many admonitions as a child for using Creole French instead of "real French," or "French French," that is, "white" French.[10] Ultimately, he concludes that "mastery of language [of the white/colonizer] for the sake of recognition as white reflects a dependency that subordinates the black's humanity".[21]

Although Fanon wrote Black Skin, White Masks while still in France, most of his work was written in North Africa. It was during this time that he produced works such as L'An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne in 1959 (Year Five of the Algerian Revolution, later republished as Sociology of a Revolution and later still as A Dying Colonialism). Fanon's original title was "Reality of a Nation"; however, the publisher, François Maspero, refused to accept this title.

Fanon is best known for the classic analysis of colonialism and decolonization, The Wretched of the Earth.[22] The Wretched of the Earth was first published in 1961 by Éditions Maspero, with a preface by Jean-Paul Sartre.[23] In it Fanon analyzes the role of class, race, national culture and violence in the struggle for national liberation. The book includes an article which focuses on the ideas of violence and decolonization. He claims that decolonization is inherently a violent process, because the relationship between the settler and the native is a binary of opposites. In fact, he uses the Biblical metaphor, "The last shall be first, and the first, last," to describe the moment of decolonization. The situation of settler colonialism creates within the native a tension which grows over time and in many ways is fostered by the settler. This tension is initially released among the natives, but eventually it becomes a catalyst for violence against the settler. His work would become an academic and theoretical foundation for many revolutions.[24]

Fanon uses the Jewish people to explain how the prejudice expressed towards blacks cannot not be generalized to other races or ethnicities. He discusses this in Black Skins, White Masks, and pulls from Jean-Paul Sartre's Reflections on the Jewish Question to inform his understanding of French colonialism relationship with the Jewish people and how it can be compared and contrasted with the oppressions of Blacks across the world. In his seminal book, Fanon issues many rebuttals to Octave Mannoni's Prospero and Caliban: The Psychology of Colonization. Mannoni asserts that "colonial exploitation is not the same as other forms of exploitation, and colonial racialism is different from other kinds of racialism." Fanon responds by arguing that racism or anti-Semitism, colonial or otherwise, are not different because they rip away a person's ability to feel human. He says "I am deprived of the possibility of being a man. I cannot disassociate myself from the future that is proposed for my brother. Every one of my acts commits me as a man. Every one of my silences, every one of my cowardices reveals me as a man." In this same vein, Fanon echoes the philosophies of Maryse Choisy, who believed that remaining neutral in times of great injustice implied an unforgivable complicity. Specifically, Fanon mentions the ravages of racism and anti-Semitism because he believes that those who are one are necessarily the other as well. Yet he is careful to distinguish between the causes of the two. Fanon argues that the reasons for hating "The Jew" are borne from a different fear than those for hating Blacks. Bigots are scared of Jews because they are threatened by what the Jew represents. The many tropes and stereotypes of Jewish cruelty, laziness, and cunning are the antithesis of the Western work ethic. The Black man is feared for perhaps similar traits, but the impetus is different. Essentially, "The Jew" is simply an idea, but Blacks are feared for their physical attributes. Jewishness is not easily detectable to the naked eye, but race is.

Both books established Fanon in the eyes of much of the Third World as the leading anti-colonial thinker of the 20th century.

Fanon's three books were supplemented by numerous psychiatry articles as well as radical critiques of French colonialism in journals such as Esprit and El Moudjahid.

The reception of his work has been affected by English translations which are recognized to contain numerous omissions and errors, while his unpublished work, including his doctoral thesis, has received little attention. As a result, it has been argued Fanon has often been portrayed as an advocate of violence (it would be more accurate to characterize him as a dialectical opponent of nonviolence) and that his ideas have been extremely oversimplified. This reductionist vision of Fanon's work ignores the subtlety of his understanding of the colonial system. For example, the fifth chapter of Black Skin, White Masks translates, literally, as "The Lived Experience of the Black" ("L'expérience vécue du Noir"), but Markmann's translation is "The Fact of Blackness", which leaves out the massive influence of phenomenology on Fanon's early work.[25]

For Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth, the colonizer's presence in Algeria is based on sheer military strength. Any resistance to this strength must also be of a violent nature because it is the only "language" the colonizer speaks. Thus, violent resistance is a necessity imposed by the colonists upon the colonized. The relevance of language and the reformation of discourse pervades much of his work, which is why it is so interdisciplinary, spanning psychiatric concerns to encompass politics, sociology, anthropology, linguistics and literature.

His participation in the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale from 1955 determined his audience as the Algerian colonized. It was to them that his final work, Les damnés de la terre (translated into English by Constance Farrington as The Wretched of the Earth) was directed. It constitutes a warning to the oppressed of the dangers they face in the whirlwind of decolonization and the transition to a neo-colonialist, globalized world.[26]

An often overlooked aspect of Fanon's work is that he did not like to write his own pieces. Instead, he would dictate to his wife, Josie, who did all of the writing and, in some cases, contributed and edited.[21]

Influences

Fanon was influenced by a variety of thinkers and intellectual traditions including Jean-Paul Sartre, Lacan, Négritude, and Marxism.[6]

Aimé Césaire was a particularly significant influence in Fanon's life. Césaire, a leader of the Négritude movement, was teacher and mentor to Fanon on the island of Martinique.[27] Fanon was first introduced to Négritude during his lycée days in Martinique when Césaire coined the term and presented his ideas in La Revue Tropique, the journal that he edited with his wife, in addition to his now classic Cahier d'un retour au pays natal[28]. Fanon referred to Césaire's writings in his own work. He quoted, for example, his teacher at length in "The Lived Experience of the Black Man", a heavily anthologized essay from Black Skins, White Masks.[29]

Legacy

Fanon has had an influence on anti-colonial and national liberation movements. In particular, Les damnés de la terre was a major influence on the work of revolutionary leaders such as Ali Shariati in Iran, Steve Biko in South Africa, Malcolm X in the United States and Ernesto Che Guevara in Cuba. Of these only Guevara was primarily concerned with Fanon's theories on violence; for Shariati, Biko and also Guevara the main interest in Fanon was "the new man" and "black consciousness" respectively.[30]

With regard to the American liberation struggle more commonly known as The Black Power Movement, Fanon's work was especially influential. His book Wretched of the Earth is quoted directly in the preface of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) and Charles Hamilton's book, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation[31] which was published in 1967, shortly after Carmichael left the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In addition, Carmichael and Hamilton include much of Fanon's theory on Colonialism in their work, beginning by framing the situation of former slaves in America as a colony situated inside a nation. "To put it another way, there is no "American dilemma" because black people in this country form a colony, and it is not in the interest of the colonial power to liberate them" (Ture Hamilton, 5).[31] Another example is the indictment of the black middle class or what Fanon called the "colonized intellectual" as the indoctrinated followers of the colonial power. Fanon states, "The native intellectual has clothed his aggressiveness in his barely veiled desire to assimilate himself to the colonial world" (47).[24] A third example is the idea that the natives (African Americans) should be constructing new social systems rather than participating in the systems created by the settler population. Ture and Hamilton contend that "black people should create rather than imitate" (144).[31]

The Black Power group that Fanon had the most influence on was the Black Panther Party (BPP). In 1970 Bobby Seale, the Chairman of the BPP, published a collection of recorded observations made while he was incarcerated entitled Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton.[32] This book, while not an academic text, is a primary source chronicling the history of the BPP through the eyes of one of its founders. While describing one of his first meetings with Huey P. Newton, Seale describes bringing him a copy of Wretched of the Earth. There are at least three other direct references to the book, all of them mentioning ways in which the book was influential and how it was included in the curriculum required of all new BPP members. Beyond just reading the text, Seale and the BPP included much of the work in their party platform. The Panther 10 Point Plan contained 6 points which either directly or indirectly referenced ideas in Fanon's work including their contention that there must be an end to the "robbery by the white man," and "education that teaches us our true history and our role in present day society" (67).[32] One of the most important elements adopted by the BPP was the need to build the "humanity" of the native. Fanon claimed that the realization by the native that s/he was human would mark the beginning of the push for freedom (33).[24] The BPP embraced this idea through the work of their Community Schools and Free Breakfast Programs.

Bolivian indianist Fausto Reinaga also had some Fanon influence and he mentions The Wretched of the Earth in his magnum opus La Revolución India, advocating for decolonisation of native South Americans from European influence. In 2015 Raúl Zibechi argued that Fanon had become a key figure for the Latin American left.[33]

Fanon's influence extended to the liberation movements of the Palestinians, the Tamils, African Americans and others. His work was a key influence on the Black Panther Party, particularly his ideas concerning nationalism, violence and the lumpenproletariat. More recently, radical South African poor people's movements, such as Abahlali baseMjondolo (meaning 'people who live in shacks' in Zulu), have been influenced by Fanon's work.[34] His work was a key influence on Brazilian educationist Paulo Freire, as well.

Fanon has also profoundly affected contemporary African literature. His work serves as an important theoretical gloss for writers including Ghana's Ayi Kwei Armah, Senegal's Ken Bugul and Ousmane Sembène, Zimbabwe's Tsitsi Dangarembga, and Kenya's Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. Ngũgĩ goes so far to argue in Decolonizing the Mind (1992) that it is "impossible to understand what informs African writing" without reading Fanon's Wretched of the Earth.[35]

The Caribbean Philosophical Association offers the Frantz Fanon Prize for work that furthers the decolonization and liberation of mankind.[36]

Fanon's writings on black sexuality in Black Skin, White Masks have garnered critical attention by a number of academics and queer theory scholars. Interrogating Fanon's perspective on the nature of black homosexuality and masculinity, queer theory academics have offered a variety of critical responses to Fanon's words, balancing his position within postcolonial studies with his influence on the formation of contemporary black queer theory.[37][38][39][40][41][42]

Bibliography

Fanon's writings

- Black Skin, White Masks (1952), (1967 translation by Charles Lam Markmann: New York: Grove Press)

- A Dying Colonialism (1959), (1965 translation by Haakon Chevalier: New York, Grove Press)

- The Wretched of the Earth (1961), (1963 translation by Constance Farrington: New York: Grove Weidenfeld)

- Toward the African Revolution (1964), (1969 translation by Haakon Chevalier: New York: Grove Press)

Books on Fanon

- Anthony Alessandrini (ed.), Frantz Fanon: Critical Perspectives (1999, New York: Routledge)

- Stefan Bird-Pollan, Hegel, Freud and Fanon: The Dialectic of Emancipation (2014, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.)

- Hussein Abdilahi Bulhan, Frantz Fanon and the Psychology Of Oppression (1985, New York: Plenum Press), ISBN 0-306-41950-5

- David Caute, Frantz Fanon (1970, London: Wm. Collins and Co.)

- Alice Cherki, Frantz Fanon. Portrait (2000, Paris: Éditions du Seuil)

- Patrick Ehlen, Frantz Fanon: A Spiritual Biography (2001, New York: Crossroad 8th Avenue), ISBN 0-8245-2354-7

- Peter Geismar, Fanon (1971, Grove Press)

- Irene Gendzier, Frantz Fanon: A Critical Study (1974, London: Wildwood House), ISBN 0-7045-0002-7

- Nigel C. Gibson (ed.), Rethinking Fanon: The Continuing Dialogue (1999, Amherst, New York: Humanity Books)

- Nigel C. Gibson, Fanon: The Postcolonial Imagination (2003, Oxford: Polity Press)

- Nigel C. Gibson, Fanonian Practices in South Africa (2011, London: Palgrave Macmillan)

- Nigel C. Gibson (ed.), Living Fanon: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (2011, London: Palgrave Macmillan)

- Lewis R. Gordon, Fanon and the Crisis of European Man: An Essay on Philosophy and the Human Sciences (1995, New York: Routledge)

- Lewis Gordon, What Fanon Said (2015, New York, Fordham) ISBN 9780823266081

- Lewis R. Gordon, T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, & Renee T. White (eds), Fanon: A Critical Reader (1996, Oxford: Blackwell)

- Peter Hudis, Frantz Fanon: Philosopher of the Barricades (2015, London: Pluto Press)

- Christopher J. Lee, Frantz Fanon: Toward a Revolutionary Humanism (2015, Athens, OH: Ohio University Press)

- David Macey, Frantz Fanon: A Biography (2000, New York: Picador Press), ISBN 0-312-27550-1

- Richard C. Onwubanibe, A Critique of Revolutionary Humanism: Frantz Fanon (1983, St. Louis: Warren Green)

- Ato Sekyi-Otu, Fanon's Dialectic of Experience (1996, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press)

- T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, Frantz Fanon: Conflicts and Feminisms (1998, Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.)

- Renate Zahar, Frantz Fanon: Colonialism and Alienation (1969, trans. 1974, Monthly Review Press)

- Alexander V. Gordon, Frantz Fanon and the Fight for National Liberation (1977, Nauka, Moscow, in Russian)

Films on Fanon

- Isaac Julien, Frantz Fanon: Black Skin White Mask (a documentary) (1996, San Francisco: California Newsreel)

- Frantz Fanon, une vie, un combat, une œuvre, a 2001 documentary

- Concerning Violence: Nine scenes from the Anti-Imperialist Self-Defense, a 2014 documentary film written and directed by Göran Olsson which is based on Frantz Fanon's essay, Concerning Violence, from his 1961 book The Wretched of the Earth.

References

- ↑ "Biography of Frantz Fanon". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ↑ Seb Brah. "Franz Fanon à Dehilès: « Attention Boumedienne est un psychopathe". academia.edu.

- ↑ Lewis Gordon, Fanon and the Crisis of European Man (1995), New York: Routledge.

- ↑ Hussein Abdilahi Bulhan, Frantz Fanon and the Psychology of Oppression (1985), New York: Plenum Press.

- ↑ Fanon, Frantz. "Full text of "Concerning Violence"". Openanthropology.org.

- 1 2 Alice Cherki, Frantz Fanon. Portrait (2000), Paris: Seuil.

- 1 2 David Macey, Frantz Fanon: A Biography (2000), New York: Picador Press.

- ↑ Nigel Gibson, Fanonian Practices in South Africa, University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg, 2011.

- ↑ Gordon, Lewis R.; Cornell, Drucilla (2015-01-01). What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to His Life and Thought. Fordham University Press. ISBN 9780823266081.

- 1 2 3 4 Gordon, Lewis R.; Cornell, Drucilla (2015-01-01). What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to His Life and Thought. Fordham University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780823266081.

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "Frantz Fanon". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015.

- ↑ Nicholls, Tracey. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://www.iep.utm.edu/fanon/#H1

- ↑ David Macey, "Frantz Fanon, or the Difficulty of Being Martinican", History Workshop Journal, Project Muse. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Fanon, Frantz (2015). Écrits sur l'aliénation et la liberté. Éditions La Découverte, Paris. ISBN 9782707188717

- 1 2 3 Alice Cherki, Frantz Fanon. Portrait (2000), Paris: Seuil; David Macey, Frantz Fanon: A Biography (2000), New York: Picador Press.

- 1 2 Cherki, Alice (2006). Frantz Fanon: A Portrait. Cornell University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8014-7308-1.

- ↑ Nicholls, Tracey. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'.'http://www.iep.utm.edu/fanon/#H1

- ↑ Angelo Codevilla, Informing Statecraft (1992, New York).

- ↑ Bhabha, Homi K. "Foreword: Framing Fanon" (PDF). Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ↑ Frantz FANON (29 October 2015). Écrits sur l'aliénation et la liberté. LA DECOUVERTE. p. 14. ISBN 978-2-7071-8871-7.

- 1 2 3 Gordon, Lewis (2015). What Fanon Said. New York: Fordham University Press.

- ↑ Sartre, Jean-Paul. "Preface". Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (1967, New York: Grove Press)

- ↑ "Extraits de la préface de Jean-Paul Sartre au "Les Damnés de la Terre" (Extracts from the preface by Jean-Paul Sartre to The Wretched of the Earth)" (in French) (Winter 1996 ed.). Tambour Journal. Retrieved 14 February 2007.

- 1 2 3 1925-1961., Fanon, Frantz, (1983). The wretched of the earth. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 9780140224542. OCLC 12480619.

- ↑ Moten, Fred (Spring 2008). "The Case of Blackness". Criticism. 50 (2): 177–218. doi:10.1353/crt.0.0062.

- ↑ "Two centuries ago, a former European colony decided to catch up with Europe. It succeeded so well that the United States of America became a monster, in which the taints, the sickness and the inhumanity of Europe have grown to appalling dimensions. Comrades, have we not other work to do than to create a third Europe? [...] It is a question of the Third World starting a new history of Man, a history which will have regard to the sometimes prodigious theses which Europe has put forward, but which will also not forget Europe's crimes, of which the most horrible was committed in the heart of man, and consisted of the pathological tearing apart of his functions and the crumbling away of his unity. And in the framework of the collectivity there were the differentiations, the stratification and the bloodthirsty tensions fed by classes; and finally, on the immense scale of humanity, there were racial hatreds, slavery, exploitation and above all the bloodless genocide which consisted in the setting aside of fifteen thousand millions of men. So, comrades, let us not pay tribute to Europe by creating states, institutions and societies which draw their inspiration from her." The Wretched of the Earth – "Conclusions".

- ↑ The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, second edition, 2010, p. 1438.

- ↑ Gordon, Lewis R.; Cornell, Drucilla (2015-01-01). What Fanon Said: A Philosophical Introduction to His Life and Thought. Fordham University Press. ISBN 9780823266081.

- ↑ Imre Szeman and Timothy Kaposy (eds), Cultural Theory: An Anthology, 2011, Wiley-Blackwell, p. 431.

- ↑ Lewis R. Gordon, T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, & Renee T. White (eds), Fanon: A Critical Reader (1996: Oxford: Blackwell), p. 163, and Bianchi, Eugene C., The Religious Experience of Revolutionaries (1972: Doubleday), p. 206.

- 1 2 3 1941-1998., Carmichael, Stokely, (1992). Black power : the politics of liberation in America. Hamilton, Charles V. (Vintage ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0679743138. OCLC 26096713.

- 1 2 1936-, Seale, Bobby, (1991). Seize the time : the story of the Black Panther party and Huey P. Newton. Baltimore, Md.: Black Classic Press. ISBN 093312130X. OCLC 24636234.

- ↑ Red-hot interest in Fanon, Raul Zibechi, 2015

- ↑ Nigel C. Gibson, "Upright and free: Fanon in South Africa, from Biko to the shackdwellers' movement (Abahlali baseMjondolo)", Social Identities, 14:6, 2008, pp. 683–715.

- ↑ Vincent B. Leitch et al. (eds), The Norton Anthology of Theory & Criticism, second edition 2010: New York: W. W. Norton & Company [www.politicsweb.co.za/politicsweb/view/politicsweb/en/page71619?oid=393903&sn=Detai], Politicsweb, 25 July 2013.

- ↑ Enrique Dussel website Archived 2010-04-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Alessandrini, Anthony C. (1999). Frantz Fanon: Critical Persepectives. Routledge.

- ↑ Pellegrini, Ann (1997). Performance Anxieties: Staging Psychoanalysis, Staging Race. Routledge.

- ↑ Stecopoulos, Harry (1997). "Fanon: Race and Sexuality". Race and the Subject of Masculinities. Duke University Press. pp. 31–38.

- ↑ Mars-Jones, Adam. "Black is the colour".

- ↑ Mercer, Kobena (1996). "The fact of Blackness: Frantz Fanon and Visual Representation". In Read, Alan. Decolonization and Disappointment: Reading Fanon's Sexual Politics. Seattle: Bay Press.

- ↑ Fuss, Diana (1994). "Interior Colonies: Frantz Fanon and the Politics of Identification". Diacritics. 24 (2/3): 19–42. doi:10.2307/465162. JSTOR 465162.

Further reading

- Staniland, Martin (January 1969). "Frantz Fanon and the African political class". African Affairs. 68 (270): 4–25. JSTOR 719495.

- Hansen, Emmanuel (1974). "Frantz Fanon: portrait of a revolutionary intellectual". Transition. 46: 25–36. JSTOR 2934953.

- Decker, Jeffrey Louis (1990). "Terrorism (un) veiled: Frantz Fanon and the women of Algiers". Cultural Critique. 17: 177–95. doi:10.2307/1354144. JSTOR 1354144.

- Mazrui, Alamin (1993). "Language and the quest for liberation in Africa: The legacy of Frantz Fanon". Third World Quarterly. 14 (2): 351–63. doi:10.1080/01436599308420329.

- Adam, Hussein M. (October 1993). "Frantz Fanon as a democratic theorist". African Affairs. 92 (369): 499–518. JSTOR 723236.

- Gibson, Nigel (1999). "Beyond manicheanism: Dialectics in the thought of Frantz Fanon". Journal of Political Ideologies. 4 (3): 337–64. doi:10.1080/13569319908420802.

- Grohs, G. K. (2008). "Frantz Fanon and the African revolution". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 6 (4): 543–56. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00017778.

- Tronto, Joan (December 2004). "Frantz Fanon". Contemporary Political Theory, Special Feature: Roundtable on Political Theory Revisited. Palgrave Macmillan. 3 (3): 245–52. doi:10.1057/palgrave.cpt.9300182. Pdf.

- von Holdt, Karl (March 2013). "The violence of order, orders of violence: Between Fannon and Bourdieu". Current Sociology, special issue: Violence and Society. Sage. 61 (2): 112–31. doi:10.1177/0011392112456492.

- Shatz, Adam (January 2017). Where Life Is Seized, London Review of Books, Vol. 39 No. 2, pages 19–27

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Frantz Fanon |

- Frantz Fanon Archive at Marxists Internet Archive

- Frantz Fanon Foundation (in French)

- Frantz Fanon: the cause of colonized peoples (in French) (archived February 2011)

- Frantz Fanon on IMDb

- Interview with Josie Fanon (Fanon's widow) in New York, November 1978 (in French and English)