Julius Nyerere

| Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Julius Nyerere on a visit to the Netherlands in 1965 | |

| 1st President of Tanzania | |

|

In office 29 October 1964 – 5 November 1985 | |

| Vice President |

Abeid Karume Aboud Jumbe Ali Hassan Mwinyi |

| Prime Minister |

Rashidi Kawawa Edward Sokoine Cleopa Msuya Edward Sokoine Salim Ahmed Salim |

| Preceded by |

Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Tanganyika Abeid Karume as President of the People's Republic of Zanzibar and Pemba |

| Succeeded by | Ali Hassan Mwinyi |

| President of the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar | |

|

In office 26 April 1964 – 29 October 1964 | |

| Vice President |

Abeid Karume (First) Rashidi Kawawa (Second) |

| President of Tanganyika | |

|

In office 9 December 1962 – 26 April 1964 | |

| Prime Minister | Rashidi Kawawa |

| Prime Minister of Tanganyika | |

|

In office 1 May 1961 – 22 January 1962 | |

| Monarch | Queen Elizabeth II |

| Preceded by | Himself (as Chief Minister) |

| Succeeded by | Rashidi Kawawa |

| Chief Minister of Tanganyika | |

|

In office 2 September 1960 – 1 May 1961 | |

| Monarch | Queen Elizabeth II |

| Governor | Sir Richard Turnbull |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as Prime Minister) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Kambarage Nyerere 13 April 1922 Butiama, Tanganyika |

| Died |

14 October 1999 (aged 77)[1] London, United Kingdom |

| Resting place | Butiama, Tanzania |

| Nationality | Tanzanian |

| Political party |

CCM (1977–1999) TANU (1954–1977) |

| Spouse(s) | [2] |

| Children |

8

|

| Residence | Butiama |

| Alma mater |

The Makerere University(DipEd) University of Edinburgh (MA) |

| Profession | Teacher |

| Awards |

Lenin Peace Prize Gandhi Peace Prize Joliot-Curie Medal |

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (Swahili pronunciation: [ˈdʒuːliəs kɑmˈbɑɾɑgə njɛˈɾɛɾɛ]; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as its Prime Minister from 1961 to 1963 and then as its President from 1963 to 1964, after which he led its successor state, Tanzania, as its President from 1964 until 1985. He was a founding member of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) party and later a member of the Chama Cha Mapinduzi party. Ideologically an African nationalist and African socialist, he promoted a political philosophy known as Ujamaa.

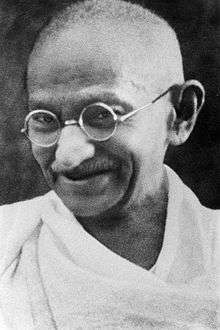

Born in Butiama, then in the British colony of Tanganyika, Nyerere was the son of a Zanaki chief. After completing his schooling, he studied at Makerere College in Uganda and then Edinburgh University in Scotland. In 1952 he returned to Tanganyika, married, and worked as a teacher. In 1954, he helped form TANU, through which he campaigned for Tanganyikan independence from the British Empire. Influenced by the Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi, Nyerere preached non-violent protest to achieve their aims. Elected to the Legislative Council in the 1958–59 elections, Nyerere then led TANU to victory at the 1960 general election, becoming Prime Minister. Negotiations with the British authorities resulted in Tanganyikan independence in 1961. In 1962, Tanganyika became a republic, with Nyerere elected its first president. His administration pursued decolonisation and the "Africanisation" of the civil service while promoting unity between indigenous Africans and the country's Asian and European minorities. He encouraged the formation of a one-party state and unsuccessfully pursued the Pan-Africanist formation of an East African Federation. A 1963 mutiny within the army was suppressed with British assistance.

In 1964, Tanganyika was unified with Zanzibar to form Tanzania. Nyerere placed a growing emphasis on socialism and national self-reliance, while developing close links with Mao Zedong's People's Republic of China. In 1967, Nyerere issued the Arusha Declaration, which outlined his vision of ujamaa. Banks and other major industries and companies were nationalised. Renewed emphasis was placed on agricultural development through the formation of communal farms. These reforms hampered food production and left Tanzania dependent on foreign food aid. Nyerere oversaw Tanzania's 1978–79 war with Uganda, resulting in the overthrow of Ugandan President Idi Amin. In 1985, Nyerere stood down and was succeeded by Ali Hassan Mwinyi. He remained the chairman of the Chama Cha Mapinduzi for another five years until 1990. He died of leukemia in London in 1999.

Nyerere is still a controversial figure. Across Africa he gained widespread respect as an anti-colonialist, although his government employed massive forced relocations of its people, was accused of economic mismanagement, and criticised for using detention without trial to deal with domestic dissent. He is held in deep respect within Tanzania, where he is often referred to by the Swahili honorific Mwalimu ("teacher"), and described as the "Father of the Nation". A cult of personality revolves around him and the country's Roman Catholic community have attempted to beatify him.

Early life

Childhood: 1922–1934

Julius Kambarage Nyerere was born on 13 April 1922 in Mwitongo, an area in the town of Butiama in Tanganyika's Mara Region.[3][4] He was one of 26 surviving children of Nyerere Burito, the chief of the Zanaki people.[5] Burito had been born in 1860 and given the name "Nyerere" ("caterpillar" in Zanaki) after a plague of worm caterpillars infested the local area at the time of his birth.[6] Burito had been appointed chief in 1915, installed in that position by the German imperial administrators of what was then German East Africa;[6] his position was also endorsed by the incoming British imperial administration.[7] Burito had 22 wives, of whom Julius' mother, Mugaya Nyang'ombe, was the fifth.[8] She had been born in 1892 and had married the chief in 1907, when she was fifteen.[9] Mugaya bore Burito four sons and four daughters, of which Nyerere was the second child; two of his siblings died in infancy.[10]

These wives lived in various huts around Burito's cattle corral, in the centre of which was his roundhouse.[11] The Zanaki were one of the smallest of the 120 tribes in the British colony and were then sub-divided among eight chiefdoms; they would only be united under the kingship of Chief Wanzagi Nyerere, Burito's half-brother, in the 1960s.[12] Nyerere's clan were the Abhakibhweege.[13] At birth, Nyerere was given the personal name "Mugendi" ("Walker" in Zanaki) but this was soon changed to "Kambarage", the name of a female rain spirit, at the advice of a omugabhu diviner.[14] Nyerere was raised into the polytheistic belief system of the Zanaki,[15] and lived at his mother's house, assisting in the farming of the millet, maize and cassava.[14] With other local boys he also took part in the herding of goats and cattle.[16] At some point he underwent the Zanaki's traditional circumcision ritual at Gabizuryo.[14] As the son of a chief he was exposed to African-administered power and authority,[17] and living in the compound gave him an appreciation for communal living that would influence his later political ideas.[18]

Schooling: 1934–1942

The British colonial administration encouraged the education of chiefs' sons, believing that this would help to perpetuate the chieftain system and prevent the development of a separate educated indigenous elite who might challenge colonial governance.[19] At his father's prompting, Nyerere began his education at the Native Administration School in Mwisenge, Musoma in February 1934, about 25 miles from his home.[20] This placed him in a privileged position; most of his contemporaries at Butiama could not afford a primary education.[21] Nyerere excelled at the school, and after six months his exam results were such that he was allowed to skip a grade.[22] He avoided sporting activities and preferred to read in his dormitory during free time.[23] His education allowed him to learn Swahili.[24]

While at the school he also underwent the Zanaki tooth filing ritual to have his upper-front teeth sharpened into triangular points.[25] It may have been at this point that he took up smoking, a habit he retained for several decades.[26] He also began to take an interest in Roman Catholicism, although was initially concerned about abandoning the veneration of his people's traditional gods.[12] With school friend Mang'ombe Marwa, Nyerere trekked 14 miles to the Nyegina Mission Centre, run by the White Fathers, to learn more about the Christian religion; although Marwa eventually stopped, Nyerere continued.[27] His elementary schooling ended in 1936; his final exam results were the highest of any pupil in the Lake Province and Western Province region.[28]

His academic excellence allowed him to gain a government scholarship to attend the elite Tabora Government School, a secondary school in Tabora.[29] There, he again avoided sporting activities but helped to set up a Boy Scout's brigade after reading Scouting for Boys.[30] Fellow pupils later remembered him as being ambitious and competitive, eager to come top of the class in examinations.[31] He used books in the school library to advance his knowledge of the English language to a high standard.[32] He was heavily involved in the school's debating society,[33] and teachers recommended him as head prefect, but this was vetoed by the headmaster, who described Nyerere as being "too kind" for the position.[34] In keeping with Zanaki custom, Nyerere entered into an arranged marriage with a girl named Magori Watiha, who was then only three or four years old but had been selected for him by his father. At the time they continued to live apart.[35] In March 1942, during Nyerere's final year at Tabora, his father died; the school refused his request to return home for the funeral.[36] Nyerere's brother, Edward Wanzagi Nyerere, was appointed as their father's successor.[37] Nyerere then decided to be baptised as a Roman Catholic;[38] at his baptism, he took on the name "Julius",[39] although later stated that it was "silly" that Catholics should "take a name other than a tribal name" on baptism.[24]

Makerere College, Uganda: 1943–1947

In October 1942, Nyerere completed his secondary education and decided to study at Makerere College in the Ugandan city of Kampala.[40] He secured a bursary to fund a teacher training course there,[41] arriving in Uganda in January 1943.[42] At Makerere, he studied alongside many of East Africa's most talented students,[43] although spent little time socialising with others, instead focusing on his reading.[44] He took courses in chemistry, biology, Latin, and Greek.[45] Deepening his Catholicism, he studied the Papal Encyclicals and read the work of Catholic philosophers like Jacques Maritain;[45] most influential however were the writings of the liberal British philosopher John Stuart Mill.[46] He won a literary competition with an essay on the subjugation of women, for which he had applied Mill's ideas to Zanaki society.[47] Nyerere was also an active member of the Makere Debating Society,[44] and established a branch of Catholic Action at the university.[45]

In July 1943, he wrote a letter to the Tanganyika Standard in which he discussed the ongoing Second World War and argued that capitalism was alien to Africa and that the continent should turn to "African socialism"; in his words, "the African is by nature a socialistic being".[48] His letter went on to state that "the educated African should take the lead" in moving the population towards a more explicitly socialist model.[49] Molony thought that the letter "serves to mark the beginnings of Nyerere's political maturation, chiefly in absorbing and developing the views of leading black thinkers of the time."[49] In 1943, Nyerere, Andrew Tibandebage, and Hamza Kibwana Bakari Mwapachu founded the Tanganyika African Welfare Association (TAWA) to assist the small number of Tanganyikan students at Makerere.[50] TAWA was allowed to die off, and in its place Nyerere revived the largely moribund Makerere chapter of the Tanganyika African Association (TAA), although this too had ceased functioning by 1947.[51] Although aware of racial prejudice from the white colonial minority, he insisted on treating people as individuals, recognising that many white individuals were not bigoted towards indigenous Africans.[52] After three years, Nyerere graduated from Makerere with a diploma in education.[53]

Early teaching: 1947–1949

On leaving Makerere, Nyerere returned home to Zanaki territory to build a house for his widowed mother, before spending his time reading and farming in Butiama.[54] He was offered teaching positions at both the state-run Tabora Boys' School and the mission-run St Mary's, but chose the latter despite it offering a lower wage.[55] He took part in a public debate with two teachers from the Tabora Boys' School, in which he argued against the statement that "The African has benefitted more than the European since the partition of Africa"; after winning the debate, he was subsequently banned from returning to the school.[56] Outside school hours, he gave free lessons in English to older locals,[57] and also gave talks on political issues.[58] He also worked briefly as a price inspector for the government, going into stores to check what they were charging, although quit the position after the authorities ignored his reports about false pricing.[59] While in Tabora, Nyerere's wife, Magori Watiha, was sent to live with him to pursue her primary education there, although he forwarded her to live with his mother.[60] Instead, he began courting Maria Gabriel, a teacher at Nyegina Primary School in Musoma; although from the Simbiti tribe, she shared with Nyerere a devout Catholicism.[61] He proposed marriage to her and they became informally engaged at Christmas 1948.[62]

In Tabora, he intensified his political activities, joining the local branch of the TAA and becoming its treasurer.[63] The branch opened a co-operative shop selling basic goods like sugar, flour, and soap.[57] In April 1946 he attended the organisation's conference in Dar Es Salaam, where the TAA officially declared itself committed to supporting independence for Tanganyika.[64] With Tibandebage he worked on rewriting the TAA's constitution and used the group to mobilise opposition to Colonial Paper 210 in the district, believing that the electoral reform was designed to further privilege the white minority.[65] At St Mary's, Father Richard Walsh—an Irish priest who was director of the school—encouraged Nyerere to consider additional education in the United Kingdom. Walsh convinced Nyerere to take the University of London's matriculation examination, which the latter passed with second division in January 1948.[66] He applied for funding from the Colonial Development and Welfare Scheme and was initially unsuccessful, although succeeded on his second attempt, in 1949.[67] He agreed to study abroad, although expressed some reluctance because it meant that he would no longer be able to provide for his mother and siblings.[68]

Edinburgh University: 1949–1952

In April 1949, boarded a plane at Dar Es Salaam and flew to Southampton in England.[69] He then travelled, by train, from London to Edinburgh.[70] In the city, Nyerere took lodgings in a building for "colonial persons" in The Grange suburb.[71] Starting his studies at the University of Edinburgh, he began with a short course in chemistry and physics and also passed Higher English in the Scottish Universities Preliminary Examination.[72] In October 1949 he was accepted for entry to study for a Master of Arts degree at the University of Edinburgh's Faculty of Arts; his was an Ordinary Degree of Master of Arts which, in contrast to common uses of the term "Master of Arts", was considered an undergraduate rather than postgraduate degree, the equivalent of a Bachelor of Arts in most British universities.[73]

In 1949, Nyerere was one of only two black students from the British East African territories studying in Scotland.[74] In the first year of his MA studies, he took courses in English literature, political economy, and social anthropology; in the latter, he was tutored by Ralph Piddington.[75] In the second, he selected courses in economic history and British history, the latter taught by Richard Pares, whom Nyerere later described as "a wise man who taught me very much about what makes these British tick".[76] In the third year, he took the constitutional law course run by Lawrence Saunders and moral philosophy.[77] Although his grades were not outstanding, they enabled him to pass all of his courses.[78] His tutor in moral philosophy described him as "a bright and lively member of the class and of the parties".[79]

Nyerere gained many friends in Edinburgh,[80] and socialised with Nigerians and West Indians living in the city.[81] There are no reports of Nyerere experiencing racial prejudice while in Scotland; although it is possible he did encounter some incidents, many black students in Britain at the time reported that white British students were generally less prejudiced than other sectors of the population.[82] In classes, he was generally treated as the equal of his white fellows, which gave him additional confidence,[78] and may have help mould his belief in multi-racialism.[83] During his time in Edinburgh, he may have engaged in part-time work to support himself and family in Tanganyika; he and other students went on a working holiday to a Welsh farm where they engaged in potato picking.[84] In 1951, he travelled down to London to meet with other Tanganyikan students and attend the Festival of Britain.[85] That same year, he co-wrote an article for The Student magazine in which he criticised plans to incorporate Tanganyika into the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, which he and co-author John Keto noted was designed to further white minority control in the region.[86] In February 1952, he attended a meeting on the issue of the Federation that was organised by the World Church Group; among those speaking at the meeting was the medical student—and future Malawian leader—Hastings Banda.[87] In July 1952, Nyerere graduated from the university with an Ordinary Degree of Master of Arts.[88] Leaving Edinburgh that week, he was granted a short British Council Visitorship to study educational institutions in England, basing himself in London.[89]

Political activism

Founding the Tanganyika African National Union: 1952–1955

Having sailed aboard the S.S. Kenya Castle, Nyerere arrive back in Dar Es Salaam in October 1952.[90] He took the train to Mwanza and then a lake steamer to Musoma before reaching Zanaki lands.[91] There, he built a mud-brick house for himself and his fiancé, Maria;[92] they were married at Musoma mission on 24 January 1953.[93] They soon moved to Pugu, closer to Dar Es Salaam, when Nyerere was hired to teach history at St Francis' College, one of the leading schools for indigenous Africans in Tanganyika.[93] He likely felt the need to secure a steady income for his family and the thought of teaching at a Roman Catholic institution likely appealed;[94] in 1953 the couple had their first child, Andrew.[95] At the same time, he became increasingly involved in politics.[96] Within three months of Nyerere's return to Tanganyika, he was elected president of the Tanganyika African Association (TAA).[91] His ability to take on the position was influenced by his good oratorical skills and by the fact that he was Zanaki; had he been from one of the larger ethnic groups he may have faced greater opposition from members of rival tribes.[97] Under Nyerere, the TAA gained an increasingly political dimension, devoted to the pursuit of Tanganyikan independence from the British Empire.[97]

On 7 July 1954 Nyerere, assisted by Oscar Kambona, transformed the TAA into a new political party, the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU).[98] Among the early TANU members were the three sons of Kleist Sykes, Dossa Aziz, and John Rupia, the latter an entrepreneur who had established himself as one of the wealthiest indigenous Africans in the country.[97] Rupia served as the group's first treasurer and largely funded the organisation in its early years.[97] The colony's governor appointed Nyerere to fill a temporary vacancy on its legislative council generated after David Makwaia was sent to London to serve on the Royal Commission for Land and Population Problems.[99] His first speech at the legislative council dealt with the need for more schools in the country.[99] When he said that he would oppose proposed government regulations to raise salaries for civil servants, the government recalled Makwaia from London to ensure Nyerere's removal.[99]

At TANU meetings, Nyerere insisted on the need for Tanganyikan independence, but maintained that the country's European and Asian minorities would not be ejected by an African-led independent government.[100] He greatly admired the Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi and endorsed Gandhi's approach to attaining independence through non-violent protest.[101] The colonial government closely monitored his activities;[102] they had concerns that Nyerere would instigate a violent anti-colonial rebellion akin to the Mau Mau Uprising in neighbouring Kenya.[103] In August 1954, the United Nations had sent a mission to Tanganyika which subsequently published a report recommending a twenty to twenty-five year timetable for the colony's independence.[99] The UN was set to discuss the issue further at a trusteeship council in New York City, with TANU sending Nyerere to be its representative there.[99] At the British government's request, the United States had agreed to prevent Nyerere staying for more than 24 hours before the meeting or moving outside an eight-block radius of the UN headquarters.[104] Nyerere arrived in the city in March 1955, as part of a trip funded largely by Rupia.[104] To the trusteeship council he said that: "with your help and with the help of the [British] Administering Authority we would be governing ourselves long before twenty to twenty-five years."[105] This seemed highly ambitious to everyone at the time.[105]

The government had also put pressure on Nyerere's employer to sack him because of his pro-independence activities.[104] On his return from New York, Nyerere resigned from the school, in part because he did not wish is ongoing employment to cause trouble for the missionaries.[106] In April 1955 he and his wife returned to his Zanaki homestead.[106] He turned down offers of employment from a newspaper and an oil company,[106] instead accepting a job as a translator and tutor for the Maryknoll Fathers, who were preparing a mission amongst the Zanaki.[106]

By the late 1950s, TANU had extended its influence throughout the country and gained considerable support.[107] TANU had 100,000 members in 1955, which had grown to 500,000 by 1957.[108]

Touring Tanganyika: 1955–1959

Nyerere returned to Dar Es Salaam in October 1955.[109] From then until Tanzania secured independence, he toured the country almost continuously, often in TANU's Land Rover.[109] The white colonial Governor of Tanganyika, Edward Twining, disliked Nyerere and regarded him as a racialist who wanted to impose indigenous domination over the European and South Asian minorities.[110] In December 1955, Twining established the United Tanganyika Party (UTP) as a "multi-racial" party with which to combat the African nationalist message of TANU.[111] Nyerere nevertheless stipulated that "we are fighting against colonialism, not against the whites".[112] He befriended members of the white minority, such as Marion the Lady Chesham, a U.S.-born widow of a British farmer, who served as a liaison between TANU and Twining's government.[113]

A 1958 editorial in the TANU newsletter Sauti ya Tanu (Voice of TANU) that had been written by Nyerere called on the party's members to avoid participating in violence.[114] It also criticised two of the country's district commissioners, accusing one of trying to undermine TANU and another of putting a chief on trial for "cooked-up reasons".[114] In response, the government filed three counts of criminal libel.[114] The trial took almost three months and resulted in a three month case.[114] Nyerere was found guilty, with the judge stipulating that he could either pay a £150 fine or go to prison for six months; he chose the former option.[115]

Twining announced that elections for a new legislative council would take place in early 1958. These would be organised along the basis of ten constituencies, each of which could elect three members of the council: one indigenous African, one European, and one South Asian.[116] This would move the country away from its concentration of political representation entirely with the European minority, but still meant that the three ethnic blocs would receive equal representation despite the fact that indigenous Africans made up over 98% of the country's population.[100] For this reason, most of TANU's leadership believed that it should boycott the election.[117] Nyerere disagreed. In his view, TANU should participate and seek to secure the majority of the indigenous African representatives to advance their political leverage. If they abstained, he argued, the UTP would win the elections, TANU would be forced to operate entirely outside of government, and it would delay the process of attaining independence.[117] At a conference in Tabora in January 1958, Nyerere convinced the rest of TANU to his viewpoint.[117] Nyerere saw it as an improvement, but which was still frustrating.[100]

In these elections, which took place over the course of 1958 and 1959, TANU won every seat that it contested.[118] Nyerere stood as TANU's candidate in the Eastern Province seat against an independent candidate, Patrick Kunambi, securing 2600 votes to Kunambi's 800.[118]

TANU in government: 1959–1961

In March 1959, the British Governor of Tanganyika, Richard Turnbull, gave TANU five of the twelve ministerial posts available in the colony's government.[118] In 1959, Nyerere returned to Edinburgh.[103] In 1960, he attended a conference of independent African states in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, a which he presented a paper calling for the formation of an East African Federation. He suggested that Tanganyika could delay its attainment of independence from the British Empire until neighbouring Kenya and Uganda were able to do the same. In his view, it would be much easier for the three countries to unite at the same point as independence than after it, for beyond that point the governments of the three states would feel that they were giving up their sovereignty through the act of unification.[119] The idea of delaying Tanganyikan independence was opposed by many senior members of TANU.[119]

In the August 1960 general election, TANU won 70 of the 71 available seats.[119] As TANU's leader, Nyerere was called to form a new government.[119]

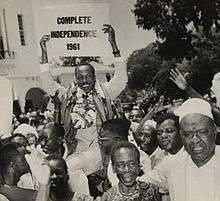

In March 1961, a constitutional conference was held in Dar Es Salaam to determine the nature of an independent constitution; it was attended by both anti-colonial campaigners and British officials.[119] As a concession to the UK's colonial secretary Iain Macleod, Nyerere agreed that after independence, Tanganyika would retain the British Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state for a year before becoming a republic.[119] In May, Tanganyika achieved self-governance.[120] One of Nyerere's first acts as Prime Minister was to stop the supply of Tanganyikan labourers to South African gold mines. Although this resulted in a loss of around £500,000 a year for Tanganyika, Nyerere regarded it as a necessary act in expressing opposition to the apartheid system of white-minority rule and racial segregation implemented in South Africa.[120]

Premiership and Presidency of Tanganyika

Premiership of Tanganyika: 1961–1962

On 9 December 1961, Tanganyika gained independence. A ceremony marking the transition was held at National Stadium and was attended by the UK's Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.[121] Six weeks after the proclamation of independence, Nyerere resigned as Prime Minister, intent on focusing on restructuring TANU and trying to "work out our own pattern of democracy".[122] Retreating to become a back bencher in the Tanganyikan parliament,[123] in his stead, he appointed close political ally Rashidi Kawawa as the new Prime Minister.[124] Many commentators believed that Nyerere had stepped down to avoid conflict with the increasingly influential African racial nationalists in his party.[125] He then began touring the country, giving speeches in towns and villages in which he emphasised the need for self-reliance and hard work.[126] In 1962, his alma mater at Edinburgh awarded Nyerere with a Honorary Degree of Doctor of Laws; Nyerere stated that receiving the honour filled him with "immense pleasure".[127]

During Tanganyika's first year of independence, its government focused largely on dealing with domestic problems.[128] Under a government self-help programme, villagers were encouraged to devote a day's work a week to a community project, such as constructing roads, wells, schools, and clinics.[129] In February 1962, the government announced its desire to convert the pervasive system of freehold land ownership into a leasehold system, the latter of which was deemed to be a better reflection of traditional indigenous ideas about communal land ownership.[130] Nyerere wrote an article, "Ujamaa" ("Familyhood") in which he explained and praised this policy; in this article he expressed many of his ideas about African socialism.[130] Six months after independence, the government abolished the jobs and salaries of hereditary chiefs, whose positions conflicted with government officials and who were often regarded as having been too closely associated with the British colonial authorities.[129] The government also pursued the "Africanization" of the civil service, giving severance pay to several hundred white British civil servants and appointing indigenous Africans in their place, many of whom were insufficiently trained.[131] Nyerere acknowledged that such affirmative action hiring was discriminatory towards white and Asian citizens, but argued that it was temporarily necessary to redress the imbalance caused by colonialism.[132] By the end of 1963, about half of senior and middle-grade posts in the civil service were held by indigenous Africans.[131]

— Julius Nyerere on the deportation of white British individuals accused of racism[133]

Over the course of the following year, a number of white British individuals living in Tanganyika were deported from the country, usually on 24 hours' notice, after they were accused of publicly expressing racist attitudes toward indigenous Africans. Concerns were raised about the lack of due process in such cases, with the deported individuals having no opportunity to defend themselves.[134] Nyerere defended the deportations, stating that "for many years we Africans have suffered humiliations in our own country. We are not going to suffer them now."[133] After the Safari Hotel in Arusha was accused of insulting Guinean President Ahmed Sékou Touré on the latter's state visit to Tanganyika in June 1963, the government ordered it to be closed immediately.[133] When the white-dominated Dar Es Salaam Club refused admission to 69 members of the government and TANU who had requested membership, the government dissolved the club and appropriated its assets.[135] Responding to cases such as this, some parts of the foreign press accused the Tanganyikan government of hypersensitivity and arrogance,[135] while Nyerere sought to avoid becoming personally embroiled in such controversies.[135]

Opposition to TANU's rule was slight, and in organised form consisted of only two small political parties:[128] the senior trade unionist Christopher S. K. Tumbo founded the People's Democratic Party, while Zuberi Mtemvu formed the African National Congress, which wanted a more radical anti-colonial stance than TANU was taking.[131] The government nevertheless thought itself vulnerable and in 1962 pushed through both a labour law banning workers' strikes and introducing a Preventative Detention Law through which it could detain without trial individuals deemed a threat to national security.[128] Nyerere defended this measure, pointing to similar laws in the United Kingdom and India, and stating that the government needed it as a safeguard given the weak state of both the police and army. He expressed the hope that the government would never have to use it, and noted that they were aware how it "could be a convenient tool in the hands of an unscrupulous government".[131]

The government drew up plans to create a new constitution which would convert Tanganyika from a monarchy with the British Queen as its head of state into a republic with an elected President as head of state. This President would be elected by the population, and they would then appoint a Vice President, who would preside over the National Assembly, Tanganyika's parliament.[123] Biographer William Edgett Smith later noted that it was "a foregone conclusion" that Nyerere would be selected as TANU's candidate for president.[136] In the November presidential election, he secured 98.1% of the vote, defeating Mtemvu.[136] After the election, Nyerere announced that TANU's National Executive Committee had voted to ask the party's national conference to widen membership to all Tanganyikans. During the anti-colonial struggle, only indigenous Africans had been permitted to join, but Nyerere now stated that it should welcome white and Asian members; he also stipulated that "complete political amnesty" should be granted to anyone expelled from the party since 1954, allowing them to rejoin.[136] In early 1963, Amir Jamal, an Asian Tanganyikan, became the party's first non-indigenous member; the white Derek Bryceson became its second.[136]

Presidency of Tanganyika: 1962–1964

On 9 December 1962, a year since Tanganyika became independent, it officially became a republic.[134] Nyerere moved into the State House in Dar Es Salaam, the former official residence of the British governors.[138] Nyerere disliked life in the building, referring to it as "my prison".[139] He remained there for three years, until 1966.[139] President Nyerere appointed Kawawa to be his Vice President.[140] In 1963, he put his name forward to be Rector of Edinburgh University, vowing to travel to Scotland whenever needed; the position instead went to the actor James Robertson Justice.[141] He made official visits to West Germany, the United States, Canada, Algeria, Scandinavia, Guinea, and Nigeria.[142]

The early years of Nyerere's presidency were preoccupied largely by African affairs.[142] In February 1963, he attended the Afro-Asian Solidarity conference in Moshi, where he cited the recent Congolese situation as an example of the neo-colonialism impacting the continent, describing it as part of a "second" Scramble for Africa.[142] In May, he attended the founding session of the Organisation for African Unity at Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, there echoing his previous message, stating that "the real humiliating truth is that Africa is not free; and therefore it is Africa which should take the necessary collective measures to free Africa."[142] He endorsed the Pan-Africanist idea of unifying Africa as a single state, although disagreed with the Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah's view that this could be achieved quickly. Instead, Nyerere stressed the idea of forming regional confederations as short-term steps towards the eventual unification of the continent.[143] Pursuing these ideals, in June 1963 Nyerere met with Kenyan President Jomo Kenyatta and Ugandan President Milton Obote in Nairobi, where they agreed to unite their respective countries into a single East African Federation by the end of the year. This, however, never materialised.[144] In December 1963, Nyerere lamented that this failure was the major disappointment of the year.[132] Later, Nyerere saw his inability to establish an East African Federation as the biggest failure of his career.[145]

Nyerere was also concerned by developments in Zanzibar, an island off of Tanganyika's coast. He noted that it was "very vulnerable to outside influences", which could in turn impact Tanganyika.[146] Zanzibar secured independence from the British Empire in 1963,[147] and in January 1964 the Zanzibar Revolution took place, in which the Arab Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah was overthrown and replaced by a government consisting largely of indigenous Africans.[148] Nyerere was taken by surprise by the revolution.[149] Like Kenya and Uganda, he quickly recognised the new government, although allowed the deposed Sultan to land in Tanganyika and from there fly to London.[149] At the request of the new Zanzibar government, he sent 300 policemen to the island to help restore order.[150]

Facing mutiny

In January 1964, Nyerere announced that the policy of affirmative action hiring for civil service jobs would end. Regarding the policy as having successfully redressed the colonial imbalance, he stated that "it would be wrong for us to continue to distinguish between Tanganyikan citizens on any grounds other than those of character and ability to do specific tasks".[132] Many trade union leaders denounced the discontinuation of the policy and it proved the catalyst for an army mutiny.[132] On 20 January, a small group of soldiers in the First Battalion calling themselves the Army Night Freedom Fighters launched an uprising, demanding that their white officers be dismissed from the army and that soldiers receive a pay rise.[151] The mutineers left the Colito Barracks and entered Dar Es Salaam, where they took control of the State House. Nyerere narrowly escaped them and went into hiding in a Roman Catholic mission in the city for two days.[152] They captured senior government figure Oscar Kambona, and forced him to dismiss all white officers from the army and appoint the indigenous Elisha Kavana as head of the Tanganyika Rifles.[153] The Second Battalion, based in Tabora, also mutineed, with Kambona acceding to their demands to appoint the indigenous Mirisho S. H. Sarakikya as their battalion leader.[154] Having agreed to many of their demands, Kambona convinced the mutineers of the First Battalion to return to their barracks.[155] Similar yet smaller mutinies broke out in Kenya and Uganda, with the governments of both of these countries calling for British military assistance in suppressing the uprisings.[156]

— Julius Nyerere on the army mutiny[157]

On 22 January, Nyerere came out of hiding and toured the city; the next day he gave a press conference stating that Tanganyika's reputation had been damaged by the mutiny and that he would not call for military assistance from the UK.[158] However, on 24 January he did request British military assistance, which was granted.[159] The following day, 60 British marine commandos were helicoptered into the city, where they landed next to the Colito Barracks; the mutineers soon surrendered.[160] In the wake of the mutiny, Nyerere disbanded the First Battalion and dismissed hundreds of soldiers from the Second Battalion.[161] Concerned about dissent more broadly, he discharged about ten percent of the 5000-strong police force, and oversaw the arrest of around 550 people under the Preventative Detention Act, although most were swiftly released.[161] He denounced the ringleaders of the mutiny for trying to "intimidate our nation at the point of a gun",[162] and fourteen of them were given sentences of between five and fifteen years imprisonment.[161] As the British marines left, he brought in the Nigerian Third Battalion to keep order.[161] Nyerere attributed the mutiny to the fact that his government had failed to do enough to change the army since colonial times: "We changed the uniforms a bit, we commissioned a few Africans, but at the top they were still solidly British... You could never consider it an army of the people."[163] Acknowledging some of the mutineers demands, he appointed Sarakikya as the new commander of the army and raised troop wages.[161]

Presidency of Tanzania

Unification with Zanzibar: 1964

Following the Zanzibari Revolution, Abeid Karume declared himself President of a one-party state and began confiscating Arab-owned land for redistribution among black African peasants.[164] Hundreds of Arabs and Indians left, as did most of the island's British community.[164] Western powers were reluctant to recognise Karume's government, whereas the Soviet Union, Eastern Bloc, and People's Republic of China quickly did so and offered the country aid.[165] Nyerere was angry at this Western response as well as the wider Western failure to appreciate why black Zanzibaris had revolted in the first place.[166] In April he visited Karume in Zanzibar.[167] The following day it was announced that Tanganyika and Zanzibar would unify to form a single country.[167] Nyerere dismissed suggestions that the unification had anything to do with Cold War power struggles, presenting it as a response to Pan-Africanist ideology: "Unity in our continent does not have to come via Moscow or Washington."[168] Later biographer William Edgett Smith however suggested that a key reason for Nyerere's desire for unification was to prevent Zanzibar falling into a Cold War proxy conflict akin to those then raging in Congo and Vietnam.[169]

An interim constitution was produced that referred to the united country as the "United Republic of Tangayika and Zanzibar". It referred to Nyerere as the country's president, with Karume as its first vice president and Rashidi Kawawa as its second vice president.[168] In August, the government launched a competition to find a new name for the country; two months later it announced that the winning proposal was "United Republic of Tanzania".[170] There was no immediate change to the structure of the Zanzibari government; Karume and his Revolutionary Council remained in charge,[171] and there was no merging of TANU and the Afro-Shirazi Party.[172] There would be no local or parliamentary elections on the island for many years.[173] Zanzibaris made up only 350,000 out of Tanzania's total population of 13 million, although from 1967 they were given seven of the 22 cabinet positions and directly appointed 40 of the country's 183 members of parliament.[174] Nyerere explained this disproportionately high representation by stressing the need for sensitivity to the islanders' national pride: in 1965, he stated that "The Zanzibaris are a proud people. No one has ever intended that they should become simply the Republic's eighteenth region."[174]

Karume was erratic and unpredictable,[175] and repeatedly embarrassed Nyerere. In one instance in August 1969, Zanzibari authorities arrested 14 men whom they accused of plotting a coup. Mainland authorities had assisted in the arrests, but—contrary to Nyerere's intentions—the arrested men were tried in secret and four of them secretly executed.[176] Nyerere was further embarrassed by the habit of Karume and other Zanzibari Revolutionary Council members for pressuring Arab girls into marriage and then arresting their relatives to ensure compliance.[177] As a result of rising international prices in cloves, Karume amassed £30 million in foreign exchange reserves, which he kept from the central Tanzanian government.[175] In April 1972, Karume was assassinated by four gun men.[178]

Domestic and foreign affairs: 1964–1966

In September 1965, a general election took place; a presidential election was held across Tanzania, while parliamentary elections took place on the mainland but not on Zanzibar.[179] Although the one-party state meant that only TANU candidates could stand, the party's national executive selected at least two candidates for all but six seats, providing some democratic choice for voters.[179] Two ministers, six junior ministers, and nine backbenchers lost their seats and were replaced.[180] Both Derek Bryceson and Amur Jamal, the two non-indigenous cabinet members, were re-elected over black opponents.[181] Nyerere stood unopposed in the presidential election, although the ballot allowed space to vote against his candidacy; ultimately he secured nearly 97% support.[182]

Tanzania experienced rapid population growth in the post-independence decades; the December 1967 census revealed a 35% increase in the population from that in 1957.[183] This rising number of children made the government's desire for universal primary education more difficult to achieve.[183] Observing that a small sector of the population were able to attain a high level of education, he grew concerned that they would form an elitist group apart from the rest of the people.[184] In 1964 he stated that "some of our citizens still have large amounts of money spent on their education, while others have none. Those who receive that privilege therefore have a duty to repay the sacrifice which others have made."[185] In October 1966, around 400 university students marched to State House to protest that they had to perform national service after completing their studies. Nyerere, Rashidi Kawana, and other cabinet members met them on the steps of the building. Nyerere spoke to the crowd in defence of national service, and agreed to reduce government salaries, including his own.[186] In 1966, Nyerere ceased using State House as his permanent residence, moving into a newly built private home on the seafront at Msasani, several miles north of Dar Es Salaam.[187]

After Tanganyika unified with Zanzibar, the latter having received support from China and other Marxist-Leninist countries, Western powers urged Nyerere not to accept support from these nations.[188] In August 1964, Nyerere allowed seven Chinese instructors and four interpreters to work with his army for six months.[188] Responding to Western disapproval, he noted that most of Tanzania's military officers were British trained and that he had recently signed an agreement with West Germany to train an air wing.[189] Over the following years, China became the main beneficiary of Tanzania's foreign relations.[189] In February 1965, Nyerere made an eight-day state visit to China, opining that their socio-economic projects in moving an agrarian country towards socialism had much relevance for Tanzania.[189] Nyerere was fascinated by Mao's China because it espoused the egalitarian values he shared;[190] he was particularly inspired by the government's emphasis on frugality and economy.[191] In June, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai visited Dar Es Salaam.[189] China provided Tanzania with millions of pounds in loans and grants, and also invested in a range of projects including a textile mill near Dar Es Salaam, a farm implement factory, an experimental farm, and a radio transmitter.[192] Seeking financial support to build a railway that would connect Zambia to the coast and through Tanzania, he secured Chinese backing in 1970 after Western countries refused to finance the operation.[193]

In the early 1960s, Nyerere had private telephone lines installed linking him to Kenyatta and Obote, although these were later eliminated in a cost-saving exercise.[194] Although the East African Federation that Nyerere desired failed to develop, he still pursued greater integration between Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya, in 1967 co-founding the East African Community, a common market and administrative union, which was headquartered in Arusha.[195] Nyerere wrote an introduction for Not Yet Uhuru, the 1967 autobiography of Kenyan leftist politician Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.[196] Nyerere's Tanzania welcomed various liberation groups from southern Africa, such as FRELIMO, to set up operations in the country to work towards overthrowing the colonial and white-minority governments of these countries.[197] Nyerere's government had warm relations with the neighbouring Zambian government of Kenneth Kaunda.[198] Conversely, it had poor relations with another neighbour, Malawi, whose leader Hastings Banda accused the Tanzanians of supporting government ministers who he claimed opposed him.[199] Nyerere strongly disapproved of Banda's co-operation with the Portuguese colonial governments in Angola and Mozambique and the white minority governments of Rhodesia and South Africa.[143] In 1967, Nyerere's government was the first to grant recognition of the newly declared Republic of Biafra, which had seceded from Nigeria. Though three other African states followed, it put Nyerere at odds with most other African nationalists.[200]

.jpg)

Nyerere signed his country to the British Commonwealth.[201] In September 1965, Nyerere threatened to withdraw Tanzania from the Commonwealth if the British government negotiated for the independence of Rhodesia with Ian Smith's white minority government rather than with representatives of the indigenous black majority.[202] When Smith's government made its unilateral declaration of independence in November, Nyerere demanded that the British take immediate direct action to stop this. When the UK failed to act effectively, in December Tanzania broke off diplomatic relations with them.[203] This resulted in the loss of British aid, but Nyerere thought it necessary to demonstrate that Africans would stand by their word.[204] He stressed that British Tanzanians remained welcome in the country and that any violence towards them would not be tolerated.[204] Despite the cessation of diplomatic contact, Tanzania cooperated with the UK in airlifting emergency oil supplies to landlocked Zambia, whose normal oil supply had been cut off by Smith's Rhodesian government.[205] In 1970, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia all threatened to leave the Commonwealth after British Prime Minister Edward Heath appeared to resume arms sales to South Africa.[206]

Relations were also strained with the United States. In November 1964, Kambona publicly announced the discovery of evidence of a U.S.-Portuguese plot to invade Tanzania. The evidence—which consisted of three photostat documents—was labelled a forgery by the U.S. Embassy and after Nyerere returned from a week at Lake Manyara he acknowledged that this was a possibility.[207] After the U.S. launched Operation Dragon Rouge to retrieve white hostages held by rebels in Stanleyville, Congo, Nyerere condemned them, expressing anger that they would go to such efforts to save 1000 white lives while doing nothing to prevent the subjugation of millions of black people in southern Africa.[208] He believed that the operation was designed to bolster the Congolese government of Moise Tshombe, which Nyerere—like many African nationalists—despised.[209] Explaining this antipathy to Tshombe, he said: "try to imagine a Jew who recruits ex-Nazis to go to Israel and assist him in his power struggle. How would the Jews take it?"[210] Relations with the U.S. reached their worst point in January 1965, when Nyerere expelled two members of the U.S. embassy for subversive activities; evidence was not publicly produced to demonstrate their guilt. The U.S. responded by expelling a councillor from the Tanzanian embassy in Washington D.C.; in turn, Tanzania recalled its ambassador, Othman Shariff.[211] After 1965, Tanzanian-U.S. relations gradually improved.[203]

The Arusha Declaration: 1967–1971

In January 1967, Nyerere embarked on a four-week tour of the Tanzanian mainland.[212] This ended in Arusha, where he attended a three-day meeting of the TANU National Executive.[212] It was there that he presented the National Executive Committee with a new statement of party principles, the Arusha Declaration.[213] This declaration affirmed the government's commitment to building a democratic socialist state and stressed that Tanzania could not rely on foreign assistance, and thus must develop an ethos of self-reliance.[212] In Nyerere's view, true independence was not possible while the country remained dependent on gifts and loans from other nations.[214] It stipulated that renewed emphasis should be placed on developing the peasant agricultural economy to ensure greater self-sufficiency, even if this meant slower economic growth.[215] After this point, the concept of socialism became central to the government's policy formation.[216] To promote the Arusha Declaration, groups of TANU supporters marched through the countryside to raise awareness; in October, Nyerere accompanied one such eight-day march which covered 138 miles in his native Mara district.[217]

The day after the declaration, the government announced the nationalisation of all Tanzanian banks, with compensation provided to their owners.[215] Over the following days, it announced plans to nationalise various insurance companies, import-export firms, mills, and sisal estates, as well as the purchase of majority interest in seven other firms, including those producing cement, cigarettes, beer, and shoes.[215] Some foreign specialists were employed to run these nationalised industries until sufficient numbers of Tanzanians had been trained to take over.[218] After a year, Nyerere praised the Tanzanian Indians for their role in ensuring the successful running of the nationalised banks, stating that "these people deserve the gratitude of our country".[218] In early 1971, the National Assembly passed a measure authorising the nationalisation of all commercial buildings, apartments, and houses worth more than 100,000 Tanzanian shillings unless the owner resided in them. This measure was designed to stop the real estate profiteering that had grown across much of post-independence Africa.[219] The measure further depleted the wealth of the Tanzanian Asian community, which had invested much in property accumulation.[220]

Nyerere followed his declaration with a series of additional policy papers covering such areas as foreign policy and rural development.[221] "Education for Self-Reliance" stressed that schools should place a new emphasis on teaching agricultural skills.[220] Another, "Socialism and Rural Development", outlined a three step process for creating ujamaa co-operative villages. The first step was to convince farmers to move into a single village, with their crops planted nearby. The second was to establish communal plots where these farmers would experiment working collectively. The third was to establish a communal farm.[220] By the end of 1970, there were reportedly a thousand villages in Tanzania referring to themselves as ujamaa.[220]

The Arusha Declaration had also announced the introduction of a code of conduct for TANU and government leaders to adhere to. This forbade them from owning shares or holding directorates in private companies, receiving more than one salary, or owning any houses that they rented to others.[215] Nyerere saw this as necessary to stem the growth of corruption in Tanzania; he was aware of how this problem had become endemic in some African countries like Nigeria and Ghana and regarded it as a threat to his vision of African freedom.[222] To ensure his own compliance with these measures, Nyerere sold his house in Magomeni and his wife donated her poultry farm in Mji Mwema to the local co-operative village.[222] In 1969, Nyerere sponsored a bill to provide gratuities for ministers and regional and area commissioners which could be used as a retirement income for them. The Tanzanian Parliament did not pass the bill into law, the first time that it had rejected legislation backed by Nyerere. The majority of parliamentarians argued that its granting of additional funds to said officials broke the spirit of the Arusha Declaration.[223] Nyerere decided not to push the issue, conceding that parliament had valid concerns about it.[224]

In June 1976, Kambona resigned from the government, ostensibly for health reasons, and relocated to London.[225] He then claimed that he had been the victim of a plot to overthrow Nyerere being orchestrated by a group opposed to the Arusha Declaration.[226] Nyerere was angered by these statements and asked Kambona to return to Tanzania.[226] By the following year, Kambona had turned against Nyerere, claiming that the latter was "making himself a dictator".[227] In October 1969 a group of army officers and former politicians, including former head of the National Women's Organisation Bibi Titi Mohamad and former Labour Minister Michael Kamaliza, were arrested, accused of plotting to kill Nyerere and overthrow the government, convicted, and imprisoned.[228]

The private sector suffered from the multiplying cumbersome, bureaucratic procedures and excessive tax rates.[229] Enormous amounts of public funds were misappropriated and put to unproductive use.[229] Purchasing power declined at an unprecedented rate and even essential commodities became unavailable.[229] A system of state permits (vibali) required for many activities allowed officials to collect huge bribes in exchange for distributing the vibali.[229] Nyerere's policies laid a foundation for systemic corruption for years to come.[229]

In 1969, Nyerere made a state visit to Canada.[203] In 1969, Nyerere informed a journalist that he was contemplating retirement from the presidency, hoping to encourage new leadership, although at the same time had a desire to remain in place to oversee the implementation of his ideas.[230] In the 1970 election, Nyerere again stood unopposed, securing 97% support for him to serve another five year term.[200] Again, parliamentary elections took place on the mainland but not in Zanzibar.[200]

In January 1971, President Obote of Uganda was overthrown by a military coup led by Idi Amin. Nyerere refused to recognise the legitimacy of Amin's administration and offered Obote refuge in Tanzania.[198] Shortly after the coup, Nyerere announced the formation of a "people's militia", a type of home guard to improve Tanzania's national security.[231] When Amin expelled all 50,000 Ugandan Asians from his country in 1972, Nyerere denounced the act as racist.[198] In September 1972, Obote loyalists launched an attack on Uganda from Tanzania, hoping to overthrow Amin.[198]

Collectivization: 1971

Collectivization was accelerated in 1971. Because much of the population resisted collectivisation, Nyerere used his police and military forces to forcibly transfer much of the population into collective farms.[232][233] Houses were set on fire or demolished, sometimes with the family's pre-Ujamaa property inside.[233] The regime denied food to those who resisted.[233] A substantial amount of the country's wealth in the form of built structures and improved land (fields, fruit trees, fences) was destroyed or forcibly abandoned.[233] Livestock was lost or stolen, or fell ill or died.[233]

In 1975, the Tanzanian government issued the "Ujamaa Program" to restructure the Sonjo region, in northern Tanzania, from compact sites with less water to flatter lands with more fertility and water. Further, new villages were created to ease the reaping of crops and raising of livestock. This "villagization" (coined by W.M. Adams) encouraged the Sonjo population to use modern irrigation techniques such as the 'unlined canals' and man-made springs (Adams 22–24). Given the diversion of water from the Kisangiro and Lelestutta Rivers by dams, river water can flow by canals into the irrigation systems to alleviate the hardships of smallholder farmers and livestock owners.[234]

Farming practices for tea and cloves improved for subsistence farmers; for example, only 3 tons of tea had been produced in 1964, yet by 1975, 2,100 tons of tea were netted from smallholder farmers. By 1974, the Ujamaa programs and the IDA (International Development Association) worked hand in hand; while villagization organized new villages to farm, the IDA financed projects to educate farmers to grow alternate crops and granted loans to farmers, with added credit to smaller farmers (Whitaker 206). Nyerere's policies had given the communal villages the opportunity to grow tea leaves despite the long history of tea being only grown in estates (208). One may understand agricultural growth through both re-organizing of traditional farms and improving the general farming methods therein, and investing into non-staple agriculture such as the aforementioned tea cultivation. Similarly, the Tanzanian government's put extensive effort into training farmers to grow tobacco effectively, which significantly improved tobacco yields to 41.9 million pounds in 1975–1976. By 1976, Tanzania became the third-largest tobacco cultivator in Africa (207). Therefore, via Tanzanian government intervention with regards to agriculture, a positive result was achieved in cheaper prices of tea and tobacco for Tanzanian villagers, consuming Tanzanian products rather than imported goods.[235]

This centralized governmental control was geared to use arable land for cash crops (specifically tobacco and tea) to benefit the government structure. As a result, food production plummeted and only foreign aid prevented mass starvation. Tanzania, which had been able to produce such vast quantities of food to both feed its population and be the largest exporter of food on the African continent, became the largest importer of food in the continent.[236][237] Many sectors of the economy collapsed; there was a virtual breakdown in transportation and goods such as toothpaste became virtually unobtainable.[236][237]

The deficit in cereal grains was more than 1 million tons between 1974 and 1977. Only loans and grants from the World Bank and the IMF in 1975 prevented Tanzania from going bankrupt. By 1979, Ujamaa villages contained 90% of the rural population but only produced 5% of the national agricultural output.[238]

Julius Nyerere announced that he would retire after presidential elections in 1985, leaving the country to enter its free market era — as imposed by structural adjustment under the IMF and World Bank – under the leadership of Ali Hassan Mwinyi, Nyerere's hand-picked successor. Nyerere was also instrumental in putting Benjamin Mkapa in power. Nyerere remained the chairman of the Chama Cha Mapinduzi (ruling party) for five years following his presidency until 1990, and is still recognized as the Father of the Nation.

Nyerere left Tanzania as one of the poorest, least developed, and most foreign aid-dependent countries in the world.[239] In 1985, he publicly apologized for his economic policies.[240] Nevertheless, Nyerere's government did much to foster social development in Tanzania during his time in office. At an international conference of the Arusha Declaration, Nyerere's successor Mwinyi noted the social gains of his predecessor's time in office: an increase in life expectancy to 52 years, a reduction in infant mortality to 137 per thousand, 2600 dispensaries, 150 hospitals, a literacy rate of 85%, two universities with over 4500 students, and 3.7 million children enrolled in primary school.[241]

Foreign policy

.jpg)

Nyerere's foreign policy emphasised nonalignment in the Cold War and under his leadership Tanzania enjoyed friendly relations with the People's Republic of China, the Soviet bloc as well as the Western world. Nyerere sided with the Chinese in the Sino-Soviet rivalry, and China reciprocated by its assistance with the building of the TAZARA Railway. When it was completed two years ahead of schedule, the TAZARA was the single longest railway in sub-Saharan Africa.[242] TAZARA was the largest single foreign-aid project undertaken by China at the time, at a construction cost of 500 million United States dollars (the equivalent of US $3.15 billion today).[243]

In July 1987, Nyerere returned to the University of Edinburgh to attend a conference on "The Making of Constitutions and the Development of National Identity", where he gave the opening address on post-independence Africa.[244]

Nyerere was instrumental in the Seychelles military coup in 1977, in which soldiers trained by Nyerere deposed the country's democratically elected president James Mancham and installed a progressive one-party socialist state under France-Albert René.[245][246][247]

In an interview with Hubert Fichte from Frankfurter Rundschau, Nyerere commented that homosexuality was alien to Africa and therefore homosexuals cannot be defended against discrimination. His comments were omitted from the publication.[248] Despite it being illegal, persecution was rare during his tenure.[249]

In doing so, Nyerere—according to A. B. Assensoh—was "one of the few African leaders to have voluntarily, gracefully, and honourably bowed out" of governance.[250]

Post-presidential activity

After the Presidency, Nyerere remained the Chairman of Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) until 1990 when Ali Hassan Mwinyi took over. Nyerere remained vocal about the extent of corruption and corrupt officials during the Mwinyi administration. However, he raised no objections when the CCM abandoned its monopoly of power in 1992. He also served as Chairman of the independent International South Commission (1987–1990), and Chairman of the South Centre in the Geneva & Dar es Salaam Offices (1990–1999).

Nyerere did not leave the political arena altogether. He campaigned in support of the CCM candidates in Tanzania's 1995 presidential election.[250] He also took part in the fifth Pan-African Congress, held in the Ugandan city of Kampala.[251] In 1997, he made his final visit to Edinburgh, delivering the Lothian European Lecture and teaching seminars at the university's Centre of African Studies.[252]

Nyerere retained enough influence to block Jakaya Kikwete's nomination for the presidency in the country's first multiparty elections in three decades, citing that he was too young to run a country. Nyerere was instrumental in getting Benjamin Mkapa elected (Mkapa had been Minister of Foreign Affairs for a time during Nyerere's administration). Kikwete later became president in 2005.

In one of his famous speeches during the CCM general assembly, Nyerere said in Swahili "Ninang'atuka", meaning that he was pulling out of politics for good. He kept to his word that Tanzania would be a democratic country. He moved back to his childhood home village of Butiama in northern Tanzania.[253] During his retirement, he continued to travel the world meeting various heads of government as an advocate for poor countries and especially the South Centre institution. Nyerere travelled more widely after retiring than he did when he was president of Tanzania. One of his last high-profile actions was as the chief mediator in the Burundi conflict in 1996.

The government and army contributed funds to build Nyerere a house in his home village; it was finished in 1999, although he only spent two weeks there prior to his death.[254]

Illness and death

By the end of his life, Nyerere had been battling chronic leukaemia for over a year. On 1 October, Nyerere was sent to intensive care due to a major stroke. He eventually passed away at the age of 77 on 14 October 1999, at around 10:30 AM at St. Thomas's Hospital in London, with his wife, Maria, and six of his eight children by his bedside. Benjamin Mkapa, Tanzanian president at the time, announced Nyerere's death on national television, and also proclaimed a 30-day mourning period. Nyerere, the former president of Tanzania, was honoured by Tanzanian state radio playing funeral music while raw video clips of him were broadcast on television.[255]

Cultural influences

Nyerere advocated for strict government control over popular culture in order to promote his vision of African pride and unity.[256] In the late 1960s, Nyerere criminalised "decadent" forms of culture including soul music, unapproved films and magazines, miniskirts, and tight trousers.[257][258]

Nyerere remained an influence upon the people of Tanzania in the years following his presidency. His broader ideas of socialism live on in the rap and hip hop tradition of Tanzania.[259] Nyerere believed socialism was an attitude of mind that countered discrimination and entailed equality of all human beings.[260] Therefore, ujamaa can be said to have created the social environment for the development of hip hop culture. As in other countries, hip hop emerged in post-colonial Tanzania when divisions among the population were prominent, whether by class, ethnicity or gender. Rappers broadcast messages of freedom, unity, and family, topics that are all reminiscent of the spirit Nyerere put forth in ujamaa.[259]

In addition, Nyerere supported the presence of foreign cultures in Tanzania saying, "a nation which refuses to learn from foreign cultures is nothing but a nation of idiots and lunatics...[but] to learn from other cultures does not mean we should abandon our own."[259]

Political ideology

Although attaining some of his early ideas from African Association contemporaries in Tanganyika,[261] many of Nyerere's political beliefs were developed while he was studying in Edinburgh; he noted that he "evolved the whole of my political philosophy while I was there".[262] In the city, he was influenced by texts he read that were produced in the tradition of European liberalism and which had also been heavily influential upon Fabian socialism.[263]

Independence, democracy, and non-racialism

Nyerere despised colonialism and felt duty bound to oppose the colonial state in Tanganyika.[264] In campaigning against colonialism, Nyerere acknowledged that he was inspired by the principles behind both the American Revolution and the French Revolution.[265] He was also influenced by the Indian independence movement, which successfully resulted in the creation of an Indian republic in 1947, just before Nyerere travelled to Britain to study.[266] Nyerere also insisted that the situation in the country was such that non-violent protest was possible and should be pursued.[267] He stated that "I'm non-violent in the sense of Mohandas Gandhi... I feel violence is an evil with which one cannot become associated unless it is absolutely necessary".[267] Nyerere was also a prominent supporter of anti-colonial liberation movements in southern Africa, providing said groups with material, diplomatic, and moral support.[268]

Although opposing European colonialism, Nyerere was not antagonistic towards white Europeans; from his experiences with them he was aware that they were not all colonialists and racists.[264] In a 1951 essay written in Edinburgh, he proposed that "We must build up a society in which we shall belong to east Africa and not to our racial groups ... We appeal to all thinking Europeans and Indians to regard themselves as ordinary citizens of Tanganyika... We are all Tanganyikans and we are all east Africans."[269] When campaigning for independence, Nyerere insisted on a non-racialist front.[267] This involvement in multi-racial politics differed from the approaches adopted by other African nationalists in Tanganyika.[270]

Nyerere emphasised the idea of democracy as a principle.[271] He described democracy as "government by the people... Ideally, it is a form of government whereby the people – all the people – settle their affairs through free discussion."[272] This is a definition close to that generated by the clergyman Theodore Parker, whose influence he acknowledged.[273] He favoured a representative democratic system within a one-party state.[273] In his 1963 essay, "Democracy and the Party System", Nyerere criticised the de facto two-party system that he had observed while in the United Kingdom, and argued in favour of one-party systems.[274] He described the two-party system as "foot-ball politics".[275] In his words, "where there is one party, and that party is identified with the nation as a whole, the foundations of democracy are firmer than they can ever be when you have two or more parties, each representing only a section of the community!"[274] Following the 1965 parliamentary election, in which different candidates from the same party competed for most seats, Nyerere noted: "I don't blame Westerners for being sceptical. The only democracies they have known have been multi-party systems, and the only one-party systems they have seen have been non-democratic. But: a multiplicity of parties does not guarantee democracy".[276]

Nyerere was keen to associate himself with the idea of freedom, titling his three major compilations of speeches and writings Freedom and Unity, Freedom and Socialism, and Freedom and Development.[266] His conception of freedom was strongly influenced by the ideas of German philosopher Immanuel Kant.[266] Like Kant, Nyerere believed that the purpose of the state was to promote liberty and the freedom of the individual.[277]

African socialism

— Julius Nyerere[190]

Nyerere was promoting "African socialism" from at least July 1943, when he wrote an article referring to the concept in the Tanganyika Standard newspaper.[278] Where he had learned the term is not clear, for it would not become widely used until the 1960s.[278] Nyerere saw socialism not as an alien idea to Africa but as something that reflected traditional African lifestyles. In his words from 1962, "We, in Africa, have no more need of being "converted" to socialism than we have of being "taught" democracy. Both are rooted in our past – in the traditional society which produced us."[279] Molony described Nyerere as having produced "romanticised accounts of idyllic village life in 'traditional society'", describing his as "a misty-eyed view" of this African past.[279] Nyerere appealed to the idea of tradition when trying to convince Tanzanians of his ideas.[280] He stated that Tanzania could only be developed "through the religion of socialism and self-reliance".[281] He reiterated the ideas of freedom, equality, and unity as being central to his concept of African socialism.[271]

Although Nyerere quoted from Karl Marx's Capital when speaking to certain audiences, he was critical of the "scientific socialism" idea promoted by Marxists like Marx and Vladimir Lenin.[282] He stated that "An African Communist has a real problem. He may study it in London, but when he comes back to Africa, he finds it's a tool he cannot apply, and then he realizes that he must become a pragmatist".[283] He added that in Africa, "we have to begin our socialism from tribal communalism and a colonial legacy which did not build much capitalism. Only South Africa has a substantial proletariat on which you could base the application of orthodox Marxism".[283] He was also critical of the "utopian socialism" promoted by figures like Henri de Saint-Simon and Robert Owen, seeing their ideas as largely irrelevant to the Tanzanian situation.[282] In his view, these European socialist writers had not produced ideas suited to the African context because they had not considered the history of "colonial domination" which Africa had experienced.[284]

Nyerere was a firm believer in egalitarianism and the creation of a society of equals,[285] and referred to his desire for a "classless society".[286] In his view, the equality of ujamaa must come from the individual's commitment to a just society in which all talents and abilities were used to the full.[287] He believed it important to balance the rights of the individual with the duty to society, expressing the view that Western countries had placed too much of an emphasis on individual rights.[288] To determine what balance to strike between the freedom of the individual and their responsibilities to society, he turned to the ideas of Genevan philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[289] His ideas on societal collectivity may also have been influenced by the work of the social anthropologist Ralph Piddington, under whom Nyerere studied at Edinburgh.[290] He detested elitism and sough to reflect that attitude in the manner in which he conducted himself as president.[291] He criticised the existence of aristocracy and the British monarchy.[292] He endorsed the equality of the sexes, stating that "it is essential that our women live on terms of full equality with their fellow citizens who are men".[293] He remained dedicated to a belief in the rule of law.[78] Nyerere's ujamaa was influenced by his reading of both Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill, both of whom he had studied as a student.[294] He stressed the need for hard work.[295]

— Julius Nyerere on socialism and religion[295]

Nyerere's belief in socialism was retained after his socialist reforms failed to generate economic growth.[296] He stated that "They keep saying you've failed. But what is wrong with urging people to pull together? Did Christianity fail because the world is not all Christian?"[296] Much of Nyerere's political ideology was inspired by his Christian belief,[297] although he stipulated the view that one did not have to be a Christian to be a socialist: "There is not the slightest necessity for people to study metaphysics and decide whether there is one God, many Gods, or no God, before they can be socialist... What matters in socialism and to socialists is that you should care about a particular kind of social relationship on this earth. Why you care is your own affair."[298] Elsewhere, he declared that "socialism is secular".[295] Trevor Huddleston thought that Nyerere could be considered both a Christian humanist,[287] and a Christian socialist.[299] In his speeches and writings, Nyerere frequently quoted from the Bible,[298] and in a 1970 address to the headquarters of the Maryknoll Mission, he argued that the Roman Catholic Church must involve itself in "the rebellion against those social structures and economic organizations which condemn men to poverty, humiliation and degradation", warning that if it failed to do so then it would lose relevance and "the Christian religion will degenerate into a series of superstitions accepted by the fearful".[300]

Personality and personal life

— Biographer Thomas Molony[301]