20th-century philosophy

| History of Western philosophy |

|---|

|

| Western philosophy |

|

|

| See also |

20th-century philosophy saw the development of a number of new philosophical schools—including logical positivism, analytic philosophy, phenomenology, existentialism, and poststructuralism. In terms of the eras of philosophy, it is usually labelled as contemporary philosophy (succeeding modern philosophy, which runs roughly from the time of René Descartes until the late 19th to early 20th centuries).

As with other academic disciplines, philosophy increasingly became professionalized in the twentieth century, and a split emerged between philosophers who considered themselves part of either the "analytic" or "Continental" traditions. However, there have been disputes regarding both the terminology and the reasons behind the divide, as well as philosophers who see themselves as bridging the divide, such as process philosophy advocates[1] and neopragmatists.[2] In addition, philosophy in the twentieth century became increasingly technical and harder for lay people to read.

The publication of Edmund Husserl's Logical Investigations (1900–1) and Bertrand Russell's The Principles of Mathematics (1903) is considered to mark the beginning of 20th-century philosophy.[3]

Analytic philosophy

Analytic philosophy is a generic term for a style of philosophy that came to dominate English-speaking countries in the 20th century. In the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Scandinavia, Australia, and New Zealand, the overwhelming majority of university philosophy departments identify themselves as "analytic" departments.[4]

Epistemology

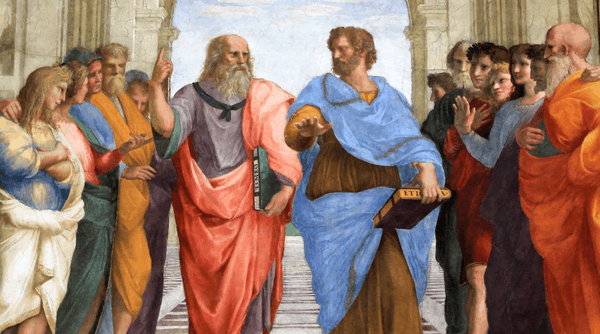

Epistemology in the Anglo-American tradition was radically shaken up by the publication of Edmund Gettier's 1963 paper "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?" This paper provided counter-examples to the traditional formulation of knowledge going back to Plato. A huge number of responses to the Gettier problem were formulated, generally falling into internalist and externalist camps, the latter including work by philosophers like Alvin Goldman, Fred Dretske, David Malet Armstrong, and Alvin Plantinga.

Logical positivism

Logical positivism (also known as logical empiricism, scientific philosophy, and neo-positivism) is a philosophy that combines empiricism—the idea that observational evidence is indispensable for knowledge—with a version of rationalism that incorporates mathematical and logico-linguistic constructs and deductions of epistemology. The Vienna Circle was a group that promoted this philosophy.[5]

Neopragmatism

Neopragmatism, sometimes called linguistic pragmatism is a recent philosophical term for philosophy that reintroduces many concepts from pragmatism. The Blackwell dictionary of Western philosophy (2004) defines "Neo-pragmatism" as follows: "A postmodern version of pragmatism developed by the American philosopher Richard Rorty and drawing inspiration from authors such as John Dewey, Martin Heidegger, Wilfrid Sellars, W.V.O. Quine, and Jacques Derrida. It repudiates the notion of universal truth, epistemological foundationalism, representationalism, and the notion of epistemic objectivity. It is a nominalist approach that denies that natural kinds and linguistic entities have substantive ontological implications.

Ordinary language philosophy

Ordinary language philosophy is a philosophical school that approaches traditional philosophical problems as rooted in misunderstandings philosophers develop by distorting or forgetting what words actually mean in everyday use. This approach typically involves eschewing philosophical "theories" in favour of close attention to the details of the use of everyday, "ordinary" language. Sometimes called "Oxford philosophy", it is generally associated with the work of a number of mid-century Oxford professors: mainly J. L. Austin, but also Gilbert Ryle, H. L. A. Hart, and Peter Strawson. The later Ludwig Wittgenstein is ordinary language philosophy's most celebrated proponent outside the Oxford circle. Second generation figures include Stanley Cavell and John Searle.

Continental philosophy

Continental philosophy, in contemporary usage, refers to a set of traditions of 19th and 20th century philosophy from mainland Europe.[6][7] This sense of the term originated among English-speaking philosophers in the second half of the 20th century, who used it to refer to a range of thinkers and traditions outside the analytic movement. Continental philosophy includes the following movements: German idealism, phenomenology, existentialism (and its antecedents, such as the thought of Kierkegaard and Nietzsche), hermeneutics, structuralism, post-structuralism, French feminism, the critical theory of the Frankfurt School and related branches of Western Marxism, and psychoanalytic theory.[8]

Existentialism

Existentialism is generally considered a philosophical and cultural movement that holds that the starting point of philosophical thinking must be the individual and the experiences of the individual. For Existentialists, religious and ethical imperatives may not satisfy the desire for individual identity, and both theistic and atheistic existentialism tend to resist mainstream religious movements. Common themes are the primacy of experience, Angst, the Absurd, and authenticity.

Marxism

Western Marxism, in terms of 20th-century philosophy, generally describes the writings of Marxist theoreticians, mainly based in Western and Central Europe; this stands in contrast with the Marxist philosophy in the Soviet Union. While György Lukács's History and Class Consciousness and Karl Korsch's Marxism and Philosophy, first published in 1923, are often seen as the works that inaugurated this current. Maurice Merleau-Ponty coined the phrase Western Marxism much later.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is the study of the phenomena of experience. It is a broad philosophical movement founded in the early years of the 20th century by Edmund Husserl. Phenomenology, in Husserl's conception, is primarily concerned with the systematic reflection on, and study of, the structures of consciousness and the phenomena that appear in acts of consciousness. This phenomenological ontology can be clearly differentiated from the Cartesian method of analysis, which sees the world as objects, sets of objects, and objects that act and react upon one another.

Post-structuralism

Post-structuralism is a label formulated by American academics to denote the heterogeneous works of a series of French intellectuals who came to international prominence in the 1960s and '70s.[9][10] The label primarily encompasses the intellectual developments of prominent mid-20th-century French and Continental philosophers and theorists.[11]

Structuralism

Structuralism is a theoretical paradigm that emphasizes that elements of culture must be understood in terms of their relationship to a larger, overarching system or "structure." Alternately, as summarized by philosopher Simon Blackburn, Structuralism is "the belief that phenomena of human life are not intelligible except through their interrelations. These relations constitute a structure, and behind local variations in the surface phenomena there are constant laws of abstract culture".[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Seibt, Johanna. "Process Philosophy". In Zalta, Edward N. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ William Egginton/Mike Sandbothe (eds.). The Pragmatic Turn in Philosophy. Contemporary Engagement between Analytic and Continental Thought. SUNY Press. 2004. Back cover.

- ↑ Spindel Conference 2002 – 100 Years of Metaethics. The Legacy of G. E. Moore, University of Memphis, 2003, p. 165.

- ↑ "Without exception, the best philosophy departments in the United States are dominated by analytic philosophy, and among the leading philosophers in the United States, all but a tiny handful would be classified as analytic philosophers. Practitioners of types of philosophizing that are not in the analytic tradition—such as phenomenology, classical pragmatism, existentialism, or Marxism—feel it necessary to define their position in relation to analytic philosophy." John Searle (2003) Contemporary Philosophy in the United States in N. Bunnin and E. P. Tsui-James (eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy, 2nd ed., (Blackwell, 2003), p. 1.

- ↑ Uebel, Thomas (17 February 2016) [First published 28 June 2006]. "Vienna Circle". In Zalta, Edward N. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2016 ed.). Stanford University: The Metaphysics Research Lab. Introduction. ISSN 1095-5054. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

While the Vienna Circle's early form of logical empiricism (or logical positivism or neopositivism: these labels will be used interchangeably here) no longer represents an active research program, recent history of philosophy of science has unearthed much previously neglected variety and depth in the doctrines of the Circle's protagonists, some of whose positions retain relevance for contemporary analytical philosophy.

- ↑ Leiter 2007, p. 2: "As a first approximation, we might say that philosophy in Continental Europe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is best understood as a connected weave of traditions, some of which overlap, but no one of which dominates all the others."

- ↑ Critchley, Simon (1998), "Introduction: what is continental philosophy?", in Critchley, Simon; Schroder, William, A Companion to Continental Philosophy, Blackwell Companions to Philosophy, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, p. 4 .

- ↑ The above list includes only those movements common to both lists compiled by Critchley 2001, p. 13 and Glendinning 2006, pp. 58–65

- ↑ Bensmaïa, Réda Poststructuralism, article published in Kritzman, Lawrence (ed.) The Columbia History of Twentieth-Century French Thought, Columbia University Press, 2005, pp. 92–93

- ↑ Mark Poster (1988) Critical theory and poststructuralism: in search of a context, section Introduction: Theory and the problem of Context, pp. 5–6

- ↑ Merquior, J.G. (1987). Foucault (Fontana Modern Masters series), University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-06062-8.

- ↑ Blackburn, Simon (2008). Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, second edition revised. Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-954143-0