Amílcar Cabral

| Amílcar Cabral | |

|---|---|

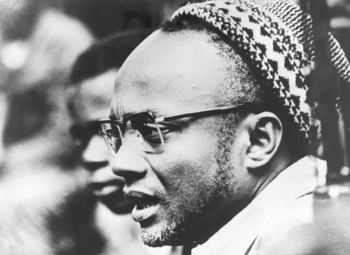

Amílcar Cabral wearing a traditional skullcap known as a sumbia during the 1964 Cassacá Congress, a gathering of PAIGC cadres. | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Amílcar Lopes da Costa Cabral 12 September 1924 Bafatá, Portuguese Guinea |

| Died |

20 January 1973 (aged 48) Conakry, Portuguese Guinea |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Political party |

African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola |

Amílcar Lopes da Costa Cabral (Portuguese: [ɐˈmilkaɾ ˈlɔpɨʃ kɐˈbɾal]; 12 September 1924 – 20 January 1973) was a Bissau-Guinean and Cape Verdean agricultural engineer, intellectual, poet, theoretician, revolutionary, political organizer, nationalist and diplomat.[1] He was one of Africa's foremost anti-colonial leaders.[2]

Also known by the nom de guerre Abel Djassi, Cabral led the nationalist movement of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde Islands and the ensuing war of independence in Guinea-Bissau. He was assassinated on 20 January 1973, about eight months before Guinea-Bissau's unilateral declaration of independence. Although not a Marxist,[3] he was deeply influenced by Marxism, and became an inspiration to revolutionary socialists and national independence movements worldwide.

Early years

Cabral was born on 12 September 1924 in Bafatá, Guinea-Bissau, to Cape Verdean parents, Juvenal Antònio Lopes da Costa Cabral and Iva Pinhel Évora, both from Santiago, Cape Verde. His father came from a wealthy land-owning family. His mother was a shop owner and hotel worker in order to support her family, especially after she separated from Amílcar's father by 1929. Her family was not well off, so she was unable to pursue higher education.

Amílcar Cabral was educated at Liceu (Secondary School) Gil Eanes in the town of Mindelo, Cape Verde, and later at the Instituto Superior de Agronomia, in Lisbon (the capital of Portugal, which was then the colonial power ruling over Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde). While an agronomy student in Lisbon, he founded student movements dedicated to opposing the ruling dictatorship of Portugal and promoting the cause of independence for the Portuguese colonies in Africa.

He returned to Africa in the 1950s, and was instrumental in promoting the independence causes of the then Portuguese colonies. He was the founder (in 1956) of the PAIGC or Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (Portuguese for African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde) and one of the founders of Movimento Popular Libertação de Angola (MPLA) (later in the same year), together with Agostinho Neto, whom he met in Portugal, and other Angolan nationalists. Cabral was an asset of the Czechoslovak State Security (StB), and under the codename "Secretary" provided intelligence information to the StB.[4]

War for independence

From 1963 to his assassination in 1973, Cabral led the PAIGC's guerrilla movement (in Portuguese Guinea) against the Portuguese government, which evolved into one of the most successful wars of independence in modern African history. The goal of the conflict was to attain independence for both Portuguese Guinea and Cape Verde. Over the course of the conflict, as the movement captured territory from the Portuguese, Cabral became the de facto leader of a large portion of what became Guinea-Bissau.

In preparation for the independence war, Cabral set up training camps in Ghana with the permission of Kwame Nkrumah. Cabral trained his lieutenants through various techniques, including mock conversations to provide them with effective communication skills that would aid their efforts to mobilize Guinean tribal chiefs to support the PAIGC. Cabral realized the war effort could be sustained only if his troops could be fed and taught to live off the land alongside the larger populace. Being an agronomist, he taught his troops to teach local crop growers better farming techniques, so that they could increase productivity and be able to feed their own family and tribe, as well as the soldiers enlisted in the PAIGC's military wing. When not fighting, PAIGC soldiers would till and plow the fields alongside the local population.

Cabral and the PAIGC also set up a trade-and-barter bazaar system that moved around the country and made staple goods available to the countryside at prices lower than that of colonial store owners. During the war, Cabral also set up a roving hospital and triage station to give medical care to wounded PAIGC soldiers and quality-of-life care to the larger populace, relying on medical supplies garnered from the USSR and Sweden. The bazaars and triage stations were at first stationary, until they came under frequent attack from Portuguese regime forces.

Death

In 1972, Cabral began to form a People's Assembly in preparation for the independence of Guinea-Bissau, but disgruntled former PAIGC rival Inocêncio Kani, together with another member of PAIGC, shot and killed him on 20 January 1973 in Conakry.[5] The possible plan was to arrest Cabral (possibly to judge him summarily, later), but facing the peaceful resistance of Cabral, they immediately killed him.

According to some theories, Portuguese PIDE agents, whose alleged plan eventually went awry, wanted to influence Cabral`s rivals through agents operating within the PAIGC, in hope of arresting Cabral and placing him under the custody of Portuguese authorities. Another theory claims that Ahmed Sékou Touré, jealous of Cabral's greater international prestige, among other motives, orchestrated the conspiracy; both theories remain unproven and controversial.

After the assassination,about one hundred officers and guerrilla soldiers of the PAIGC, accused of involvement in the conspiracy that resulted in the murder of Amílcar Cabral and the attempt to seize power in the movement, were summarily executed. His half-brother, Luís Cabral, became the leader of the Guinea-Bissau branch of the party and would eventually become President of Guinea-Bissau.

A declassified United States Department of State brief notes that the motives of his assassination are unclear but may have linked to "a feud between mulattos [sic] from the Cape Verde islands and mainland Africans."[6] Cabral was assassinated prior to the independence of the Portuguese colonies in Africa, and therefore died before he could see his homelands of Cabo Verde and Guinea Bissau gain independence from Portugal.

Tributes

...one of the most lucid and brilliant leaders in Africa, Comrade Amílcar Cabral, who instilled in us tremendous confidence in the future and the success of his struggle for liberation.

Cabral is considered a "revolutionary theoretician as significant as Frantz Fanon and Che Guevara",[7] one "whose influence reverberated far beyond the African continent."[8] Amílcar Cabral International Airport, Cape Verde's principal international airport at Sal, is named in his honor. There is also a football competition, the Amílcar Cabral Cup, in zone 2, named as a tribute to him. In addition, the only privately owned university in Guinea-Bissau — Amílcar Cabral University, in Bissau - is named after him. Jorge Peixinho composed an elegy to Cabral in 1973.

Author António Tomás wrote a biography of Amílcar Cabral, entitled O Fazedor de Utopias: Uma Biografia de Amílcar Cabral, which offers an extensive overview of Amílcar’s life in narrative form and features a detailed account of Amílcar’s family history in Portuguese.

President William R. Tolbert (Republic of Liberia) commissioned and built a housing estate on the Old Road, Sinkor, Monrovia, Liberia, named in honor of Cabral.

Films

- Cabral's political thought and role in the liberation of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde is discussed at some length in Chris Marker's film, Sans Soleil (1983). He is also the subject of the Portuguese documentary Amílcar Cabral, released in 2000.

- The documentary film Cabralista,[9] winner of the CVIFF Cape Verde International Film Festival prize for best documentary in 2011, puts Amilcar Cabral's political views and ideologies in the spotlight.[10]

Writings

- Cabral, Amilcar. Resistance and Decolonization. Translated by Dan Wood. Rowman & Littlefield International, 2016.

- Cabral, Amilcar. Return to the Source: Selected Speeches of Amilcar Cabral. Monthly Review Press, 1973.

- Cabral, Amilcar. Unity and Struggle: Speeches and Writings of Amilcar Cabral. Monthly Review Press, 1979.

References

- ↑ Martin, G. (2012-12-23). African Political Thought. Springer. ISBN 9781137062055.

- ↑ Ronald H. Chilcote, Am´lcar Cabral's Revolutionary Theory and Practica: A critical guide, Boulder & London, Lynne Rienner, 1991

- ↑ Gleijeses 1997, p. 46.

- ↑ Philip Muehlenbeck, Czechoslovakia in Africa, 1945-1968 (New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2016), 106.

- ↑ A “NIGHT OF LONG KNIVES” IN CONAKRY

- ↑ https://2001-2009.state.gov/documents/organization/67534.pdf

- 1 2 "Africa: A Continent Drenched in the Blood of Revolutionary Heroes" Victoria Brittain, The Guardian, January 17, 2011.

- ↑ Opening text of Cabralista, 2011 documentary film by Valerio Lopes

- ↑ Cabralista trailer.

- ↑ CVIFF

Further reading

- Abdel Malek, Karine, "Le processus d'accès à l'indépendance de la Guinée-Bissau.", In : Bulletin de l'Association des Anciens Elèves de l'Institut National de Langues et de Cultures Orientales, N°1, Avril 1998. - pp. 53–60

- Bienen, Henry (1977). "State and Revolution: The Work of Amilcar Cabral". Journal of Modern African Studies. 15 (4): 555–568.

- Chabal, Patrick. Amilcar Cabral: Revolutionary Leadership and People's War. New York and Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-521-24944-9.

- Chailand, Gérard. Armed Struggle in Africa: With the Guerrillas in "Portuguese" Guinea. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1969. ISBN 0-85345-106-0.

- Chilcote, Ronald H. (1968). "The Political Thought of Amílcar Cabral". Journal of Modern African Studies. 6 (3): 373–388. JSTOR 159305.

- Dhada, Mustafah. Warriors at Work. Niwot, Colorado, USA: Colorado University Press, 1993.

- Gleijeses, Piero (1997). "The First Ambassadors: Cuba's Contribution to Guinea-Bissau's War of Independence". Journal of Latin American Studies. 29 (1): 45–88. doi:10.1017/s0022216x96004646. JSTOR 158071.

- McCollester, Charles. "The Political Thought of Amilcar Cabral." Monthly Review, 24: 10–21 (March 1973).

- Sigal, Brad. Amilcar Cabral and the Revolution in Guinea-Bissau City College of New York

- TomaÌs, AntoÌnio. O Fazedor De Utopias: Uma Biografia De AmiÌlcar Cabral. Lisboa: Tinta-da-china, 2008. Print.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amílcar Cabral. |

- "The Weapon of Theory", a speech at the Tricontinental Conference in Havana, 1966

- Encyclopædia Britannica Amilcar Cabral

- "National Liberation and Culture", a speech at Syracuse University in 1970

- The African Activist Archive Project website has documents, posters, buttons, and photographs related to the struggle for independence in Guinea-Bissau and support for that struggle by U.S. organizations. The website includes photographs of Cabral.

- Works at Marxists.org

- "The Revolution in Guinea-Bissau and the Heritage of Amilcar Cabral" from Africa in Struggle, by Daniel Fogel

- Review of Amilcar Cabral's Unity & Struggle by John Newsinger in International Socialism, 12 (1981).