Kabylie

| Kabylia Tamurt n Leqbayel منطقة القبائل ⵜⴰⵎⵓⵔⵜ ⵏ ⵍⴻⵇⴱⴰⵢⴻⵍ | |

|---|---|

| Kabylie | |

Location of Kabylie in central Algeria (northwestern Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 36°48′N 4°18′E / 36.8°N 4.3°ECoordinates: 36°48′N 4°18′E / 36.8°N 4.3°E | |

| Region |

|

| Provinces - Wilayas | Tizi Ouzou, Béjaïa, Jijel, Bouïra, Boumerdès, Setif, Bordj Bou Arréridj, Médéa |

| Area | |

| • Total | 25,000 km2 (10,000 sq mi) |

| Population (2012) | |

| • Total | 7,575,643 |

| • Density | 300/km2 (780/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) |

Kabyles Iqvayliyen |

| Time zone | UTC+1 |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166-2 | KAB |

| Area code | +213 (Algéria) |

| Languages |

Kabyle (Tamazight) French language Algerian Arabic English in school |

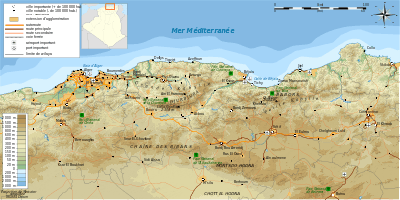

Kabylie, or Kabylia (Arabic: منطقة القبائل, Berber languages: Tamurt n Yiqbayliyen ; Tazwawa; ⵜⴰⵎⵓⵔⵜ ⵏ ⵍⴻⵇⴱⴰⵢⴻⵍ), is a cultural region, natural region, and historical region in northern Algeria. It is part of the Tell Atlas mountain range, and is located at the edge of the Mediterranean Sea.

Kabylia covers several provinces of Algeria: the whole of Tizi Ouzou and Bejaia (Bgayet), most of Bouira (Tubirett) and parts of the wilayas of Boumerdes, Jijel, Setif and Bordj Bou Arreridj. Gouraya National Park and Djurdjura National Park are also located in Kabylie.

History

Antiquity

Kabylia was a part of the Kingdom of Numidia (202 BC – 46 BC). It was later taken over by the Roman Empire, and became split between the provinces of Africa and Mauretania Caesariensis. The weakening of Roman authority during the Empire's crisis from the 250s emboldened the local tribes to cause trouble including the Quinquegenitani of the Kabylie. In 289, the governor of Mauretania Caesariensis (roughly modern Algeria) gained a temporary respite by pitting a small army against the Bavares and Quinquegentiani, but the raiders soon returned. The rebels were defeated in a year-long Roman offensive in the years 297-298 personally led by the emperor Maximian who crossed over from Spain to Mauretania where he began operations and moved eastwards. The Quinquegentiani were driven from their homeland in Kabylia, into the Sahara, Odahl, Charles Matson, Constantine and the Christian Empire. New York: Routledge, 2004. Hardcover ISBN 0-415-17485-6 Paperback ISBN 0-415-38655-1; Williams, Stephen. Diocletian and the Roman Recovery. New York: Routledge, 1997, p. 75 ISBN 0-415-91827-8.

Middle Ages

The Kabyle country remained as unconquerable as it was inaccessible to the Ottoman deys. They generally established a few coastal military settlements and some in valleys, where they enforced the rule of the Islamic Ottoman Empire. The mountainous core land, however, remained independent. Islam was gradually adopted through peaceful means, namely the Marabout movement. Some scholars argue that this is the reason of the Kabyles' indifference towards Islam.

Regency of Algiers

During the Regency of Algiers, most of Kabylia was independent. Kabylia was split into two main kingdoms, the Kingdom of Kuku in modern Tizi Ouzou, and the Kingdom of Ait Abbas in modern Béjaïa.

French colonisation and resistance

.jpg)

Though the region was the last stronghold against French colonization,[1] the area was gradually taken over by the French after 1830, despite vigorous local resistance by the local population led by leaders such as Faḍma n Sumer, until the battle of Icheriden in 1857 marked a decisive French victory, with sporadic outbursts of violence continuing as late as Mokrani's rebellion in 1871. Much land was confiscated in this period from the more recalcitrant tribes and given to French pieds-noirs. Many arrests and deportations were carried out by the French in response to uprisings, mainly to New Caledonia (hence the origins of the Algerians of the Pacific.) Colonization also resulted in an acceleration of the emigration into other areas of the country and outside of it.

Algerian migrant workers in France organized the first party promoting independence in the 1920s. Messali Hadj, Imache Amar, Si Djilani, and Belkacem Radjef rapidly built a strong following throughout France and Algeria in the 1930s and actively trained militants who became key players during the struggle for independence and in building an independent Algerian state.

In the Algerian War

During the War of Independence (1954–1962), the FLN and ALN's reorganisation of the country created, for the first time, a unified Kabyle administrative territory, wilaya III, being as it was at the centre of the anti-colonial struggle.[2] As such, along with the Aurès, it was one of the most affected areas because of the importance of the maquis (aided by the mountainous terrain) and the high levels of support and collaboration of its inhabitants for the nationalist cause. Several historic leaders of the FLN came from this region, including Hocine Aït Ahmed, Abane Ramdane, and Krim Belkacem. It was also in Kabylia that the Soummam conference took place in 1956, the first of the FLN. The flipside of being such a critical region for the independence movement was being one of the major target of French counter-insurgency operations, not least the devastation of agricultural lands, lotting, destruction of villages, population displacement, the creation of forbidden zones, etc.[3]

After independence

From the moment of independence, tensions had already developed between Kabyle leaders and the central government, with the Socialist Forces Front (FFS) party of Hocine Aït Ahmed, strong in wilayas III and IV (Kabylie and Algiers), opposing the FLN's Political Bureau centred around the person of Ahmed Ben Bella, who in turn relied upon the forces of the border army group within the ALN commanded by Houari Boumediene. As early as 1963 the FFS called into question the authority of the single-party system, which resulted in two years of armed confrontation in the region, leaving more than four hundred dead, and most of the FLN leaders from Kabylia and the eastern provinces either executed or forced into exile.[4]

In April 1980, following the banning of a conference by writer Mouloud Mammeri on traditional Kabyle poetry, riots and strikes broke out in Tizi Ouzou, followed by several months of demonstrations on university campuses in Kabylia and Algiers, known as the Berber Spring, demanding the officialisation and recognition of the Tamazight language. These resulted in the extrajudicial imprisonment of thousands of Kabylie intellectuals, along with other clashes in Tizi-Ouzou and Algiers in 1984 and 1985.[5] With the opening up and establishment of the multi-party system in 1989, the RCD (Rally for Culture and Democracy) party was created by Saïd Sadi, at the same time as identity politics and the cultural awakening of the Kabylians were intensifying in reaction to the increasingly hard-line Arabization.[6] In the midst of the civil war, there was an act of massive civil disbedience beginning in September 1994 and lasting the entire school year until mid 1995 where the ten-million strong population of Kabylia conducted a total school boycott, known as the "schoolbag strike".[7][8] In June and July 1998 the region flared up again after the assassination of protest singer and political activist Lounès Matoub at the same time that a law requiring the use of Arabic in all fields of education entered into force, further worsening tensions.[9][10]

Following the death in April 2001 of Massinissa Guermah, a young high school student, in police custody, major riots took place, known as the Black Spring, in which 123 people died and some two thousand were wounded as a result of the authorities' violent crackdown.[11] Eventually, the government was compelled to negotiate with the Arouch, a confederation of ancestral local councils over the situation, alongside wider issues such as social justice and the economy, which was deemed by the government as 'regionalist' and dangerous for national unity and cohesion.[12] Nevertheless, Tamazight was recognised in 2002 as a national language of Algeria, and as of 7 February 2016, an official language of the State alongside Arabic.[13]

The Movement for the Autonomy of Kabylie (MAK), founded in June 2001, has called for self-government for the region since 2011. The MAK is re-baptised as "Mouvement pour l'Autodétermination de la Kabylie" seeking independence from Algeria .[14]

Geography

Landscape near Azazga

Main features:

- Greater Kabylia, which runs from Thénia (west) to Bgayet (Bejaia) (east), and from the Mediterranean Sea (north) to the valley of Soummam (south), that is to say, 200 km by 100 km, beginning 50 km from Algiers, the capital of Algeria.

- Lesser Kabylia, comprising Kabylia of Bibans and Kabylia of Babors.

Three large chains of mountains occupy most of the area:

- In the north, the mountain range of maritime Kabylia, culminating with Tifrit n'Ait El Hadj (Tamgout 1278 m)

- In the south, the Djurdjura, dominating the valley of Soummam, culminating with Lalla-Khedidja (2308 m)

- Between the two lies the mountain range of Agawa, which is the most populous and is 800 m high on average. The largest town of Great Kabylia, Tizi Ouzou, lies in that mountain range. At Iraten (formerly "Fort-National" in French occupation), which numbered 28,000 inhabitants in 2001, is the highest urban centre of the area.

Ecology

There are a number of flora and fauna associated with this region. Notable is a population of the endangered primate, Barbary macaque, Macaca sylvanus, whose prehistoric range encompassed a much wider span than the present limited populations in Algeria, Morocco and Gibraltar.[15]

Population

The area is populated by the Kabyle, a Berber ethnic group. They speak the Kabyle variety of Berber. Since the Berber Spring in 1980, Kabyles have been at the forefront of the fight for recognition of the Berber language as an official one in Algeria (see Languages of Algeria).

Economy

The traditional economy of the area is based on arboriculture (orchards, olive trees) and on the craft industry (tapestry or pottery). The mountain and hill farming is gradually giving way to local industry (textile and agro-alimentary).

Today Kabylia is one of the most industrialised parts of Algeria.[16] Kabylia produces less than 15% of Algerian GDP (excluding oil and gas).[17] Industries include: pharmaceutical industry in Bgayet Bejaia, agro-alimentary in Ifri and Akbou, mechanical industry in Tizi Ouzou and other small towns of western Kabylia, and petrochemical industry and oil refining in Bgayet Bejaia.[17]

Bgayet Bejaia's port is the second biggest in Algeria after Algiers, and the 6th largest on the Mediterranean Sea.

See also

- Portal:Berbers

- Portal:Algeria

- Kabylie football team

References

- ↑ "Kabylia - Oxford Islamic Studies Online". Oxfordislamicstudies.com. 2008-05-06. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- ↑ Stora, Benjamin (2004-07-05). "Veillée d'armes en Kabylie". Le Monde.fr (in French). ISSN 1950-6244. Retrieved 2017-03-22.

- ↑ Harbi, Mohammed; Stora, Benjamin (2005). La Guerre d'Algérie. Hachette. p. 324. ISBN 2-012-79279-0.

- ↑ Le Saout, Didier; Rollinde, Marguerite (1999). Émeutes et Mouvements sociaux au Maghreb. Karthala. p. 46. ISBN 978-2-865-37998-9.

- ↑ Mourre, Michel (ed.), 'Kabyles', Dictionnaire encyclopédique d'Histoire, Paris, Bordas, Vol. 3, (1996 [1978]), p. 3082.

- ↑ Jacques Leclerc, "Algérie: Données historiques et conséquences linguistiques" sur L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde, Université Laval, 14 January 2012.

- ↑ Temlali, Yassin (1 May 2006). "Petite histoire de la question berbère en Algérie". Babel Med (in French). Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ↑ Chaker, Salem (2001). "Berber Challenge in Algeria: The State of the Question". Race, Gender & Class. 8 (3): 141. JSTOR 41674987.

- ↑ Jacques Leclerc, "Algérie: Loi no 91-05 du 16 janvier 1991 portant généralisation de l'utilisation de la langue arabe" sur L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde, Université Laval

- ↑ Jacques Leclerc, "Algérie: Les droits linguistiques des berbérophones", in L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde, Université Laval, 20 April 2010

- ↑ Algeria: Unrest and Impasse in Kabylia, International Crisis Group, Report No. 15, 10th June 2003, [read online](last accessed 24/3/2017), p. 9.

- ↑ Addi, Lahouari (2012). Algérie: Chroniques d'une expérience postcoloniale de modernisation. http://www.algeria-watch.org/farticle/analyse/addi_plateforme_elkseur.htm: Barzakh. ISBN 978-9-947-85199-9.

- ↑ "ALGERIA: Tamazight Recognised". Africa Research Bulletin: Political, Social and Cultural Series. 53 (1): 20850B–20850C. 2016-02-01. doi:10.1111/j.1467-825X.2016.06822.x. ISSN 1467-825X.

- ↑ Zirem, Youcef (2013). Histoire de Kabylie: Le point de vue kabyle. Yoran Embanner. p. 179. ISBN 978-2-914-85598-3.

- ↑ "Barbary Macaque (Macaca sylvanus) - iGoTerra.com". Globaltwitcher.auderis.se. Archived from the original on 2012-04-19. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- ↑ "Tmurt Iqvayliyen ass-agi", Maxime Ait Kaki

- 1 2 "Tadamsa taqbaylit", Saεid Duman

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kabylie. |