Evangelicalism in the United States

In the United States, evangelicalism is an umbrella group of Protestant Christians who believe in the necessity of being born again, emphasize the importance of evangelism, and affirm traditional Protestant teachings on the authority and the historicity of the Bible.[1] Nearly a quarter of the US population, evangelicals are diverse and drawn from a variety of denominational backgrounds, including Baptist, Mennonite, Methodist, Holiness, Pentecostal, Reformed and nondenominational churches.[2][3]

Evangelicalism has played an important role in shaping American religion and culture. The First Great Awakening of the 18th century marked the rise of evangelical religion in colonial America. As the revival spread throughout the Thirteen Colonies, evangelicalism united Americans around a common faith.[1] The Second Great Awakening of the 19th century led to what historian Martin Marty called the "Evangelical Empire", a period in which evangelicals dominated US cultural institutions, including schools and universities. Some evangelicals were strong advocates of reform, largely in the northern United States. They were involved in the temperance movement and supported the abolition of slavery, in addition to working towards education and criminal justice reform. Many evangelical denominations split over slavery, with evangelicals in the southern United States establishing new branches that did not formally or openly call for abolition of slavery. [4] (For example, the Southern Baptist Convention) was founded over the issue of slaveholders serving as foreign missionaries.)

By the end of the 19th century, the old evangelical consensus that had united American Protestantism no longer existed. Protestant churches became divided over new intellectual and theological ideas, such as Darwinian evolution and historical criticism of the Bible. Those who embraced these liberal ideas became known as modernists, while those who rejected them became known as fundamentalists. Fundamentalists defended the doctrine of biblical inerrancy and adopted a dispensationalist theological system for interpreting the Bible.[5] As a result of the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy of the 1920s and 1930s, fundamentalists lost control of the Mainline Protestant churches and separated themselves from non-fundamentalist churches and cultural institutions.[6]

After World War II, a new generation of conservative Protestants rejected the separatist stance of fundamentalism and began calling themselves evangelicals. Popular evangelist Billy Graham was at the forefront of reviving use of the term. During this time period, a number of evangelical institutions were established, including the National Association of Evangelicals, Christianity Today magazine and a number of educational institutions, such as Fuller Theological Seminary.[7] As a reaction to the 1960s counterculture, many evangelicals became politically active and involved in the Christian right, which became an important voting bloc of the Republican Party. Observers such as Frances FitzGerald have noted that since 2005 the influence of the Christian right among evangelicals has been in decline.[8] Though less visible, some evangelicals identify as Progressive evangelicals.

History

Evangelicals are Protestants who adhere to the Protestant Reformation doctrines of salvation by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone and believe that right doctrine comes from Scripture alone. Evangelicalism as a movement was shaped by the revivals of the First Great Awakening during the 18th-century, and it is this revival heritage that differentiates evangelicals from other Protestants.[9]

According to religion scholar Randall Balmer, evangelicalism resulted "from the confluence of Pietism, Presbyterianism, and the vestiges of Puritanism. Evangelicalism picked up the peculiar characteristics from each strain – warmhearted spirituality from the Pietists (for instance), doctrinal precisionism from the Presbyterians, and individualistic introspection from the Puritans".[10] What distinguished this new blend of early American evangelicalism from the forms of Protestantism that preceded it was, according to historian Thomas S. Kidd, "increased emphases on seasons of revival, or outpourings of the Holy Spirit, and on converted sinners experiencing God's love personally" [emphasis in original].[11]

17th century

Puritanism

Early American evangelicalism was shaped by the Puritans of New England (also known as Congregationalists), a 16th and 17th-century Calvinist movement originating in England.[12] Like later evangelicals, the Puritans believed in the necessity of a conversion experience. Before a convert was admitted to full church membership, he or she had to provide evidence of his or her conversion in the form of a conversion narrative and agree to abide by the church covenant. After agreeing to the covenant, new converts were admitted to full membership with the right of receiving the Lord's Supper and having their children baptized.[13]

Puritans believed conversion occurred in stages. The first stage was humiliation or sorrow for having sinned against God. The second stage was justification or adoption characterized by a sense of having been forgiven and accepted by God through Christ's mercy. The third stage was sanctification, the ability to live a holy life out of gladness toward God.[14]

As the children of the first generation of Puritans grew to adulthood, church leaders became concerned that many of them remained unconverted and therefore unable to have their children baptized. In 1662, the Half-Way Covenant was introduced, which allowed parents who were "baptized and moral, but not converted, to have their own children baptized." This created a situation in which Puritan churches were filled with halfway members waiting for conversion.[15]

Puritan ministers saw other signs of religious decline in New England and began to encourage a general revival of religion through covenant renewals in the 1670s and 1680s. These ceremonies, often followed by weeks of preaching on salvation, "presented an opportunity for all to consider whether they were truly right before God and also for halfway members to seek conversion and full admission into church membership."[16] According to historian Perry Miller, the First Great Awakening was "nothing more than an inevitable culmination" of the covenant renewals.[17]

The renewals, however, differed from the evangelical revivals in that covenant renewals were planned in advance. The earliest evangelicals came to believe that revivals were outpourings of the Holy Spirit that usually occurred unexpectedly.[12] Using this definition of revival, historian Thomas Kidd identified Puritan minister Samuel Torrey as the first evangelical spokesman in New England. Torrey became pastor of Weymouth, Massachusetts, in 1666, and throughout his ministry preached on the necessity of revival among ministers and congregations, calling for "Heart-reformation, or making of a new heart."[18]

Another important early figure was Solomon Stoddard of Northampton, Massachusetts. A contemporary of Torrey, Stoddard presided over five revivals or "harvests", as he referred to them, between 1679 and 1718. As a Calvinist, Stoddard believed that the Holy Spirit drew sinners to salvation, but he also believed that powerful preaching could be the means by which this occurred. With this in mind, Stoddard's preaching consisted of both warnings of damnation and hope of salvation through Christ. Stoddard's 1714 treatise on conversion, A Guide to Christ, helped shape evangelical spirituality and remained influential into the 19th century.[19]

Pietism and Scots-Irish Presbyterianism

Besides New England Puritanism, early evangelicalism was also influenced by pietism, a movement within the Lutheran and Reformed churches in Europe that emphasized a "religion of the heart": the ideal that faith was not simply acceptance of propositional truth but was an emotional "commitment of one's whole being to God" in which one's life became dedicated to self-sacrificial ministry.[20]

Pietism originated from the work of German Lutheran theologian Philipp Spener, who felt there was a lack of sincere piety or devotion within the Lutheran church of his day. Spener sought to reform the church through the renewal of individual hearts by organizing small group meetings that would encourage spiritual development. A renewed Protestant church would be able to accomplish the conversion of the Jews and bring an end to the Roman Catholic Church, both of which were believed to be necessary before the Second Coming of Christ occurred.[21]

In the 1720s and 1730s, this movement flourished in the religiously tolerant Middle Colonies as pietist clergy emigrated from Continental Europe, many of them influenced by August Hermann Francke, Willem Teellinck and Gisbertus Voetius.[22] Evangelicalism in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and the southern backcountry was also shaped by Presbyterianism. Scots-Irish immigrants brought with them traditions such as the communion season that would contribute to revivalism in America.[23] More so than other evangelicals, the Scots-Irish revivalists saw conversion as a process, potentially taking months or years.[24]

18th century

In the 1730s, evangelicalism emerged as a distinct phenomenon out of religious revivals that began in Britain and New England. It developed during the Age of Enlightenment in response to challenges to traditional Protestantism. In particular, deism—which denied that God took an active role in human history and rejected the reality of biblical miracles—had become influential within the Church of England both in Britain and across the Atlantic in the Thirteen Colonies.[25]

While religious revivals had occurred within Protestant churches in the past, the evangelical revivals that marked the 18th century were more intense and radical.[26] Evangelical revivalism imbued ordinary men and women with a confidence and enthusiasm for sharing the gospel and converting others outside of the control of established churches, a key discontinuity with the Protestantism of the previous era.[27]

It was developments in the doctrine of assurance that differentiated evangelicalism from what went before. Historian David W. Bebbington says, "The dynamism of the Evangelical movement was possible only because its adherents were assured in their faith."[28] He goes on:

Whereas the Puritans had held that assurance is rare, late and the fruit of struggle in the experience of believers, the Evangelicals believed it to be general, normally given at conversion and the result of simple acceptance of the gift of God. The consequence of the altered form of the doctrine was a metamorphosis in the nature of popular Protestantism. There was a change in patterns of piety, affecting devotional and practical life in all its departments. The shift, in fact, was responsible for creating in Evangelicalism a new movement and not merely a variation on themes heard since the Reformation.[29]

.jpg)

The most influential episode in the Great Awakening was the Northampton revival of 1734–1735 under the leadership of Congregational minister Jonathan Edwards, grandson and successor to Solomon Stoddard.[30] In the fall of 1734, Edwards preached a sermon series on justification by faith alone, and the community's response was extraordinary. Signs of religious commitment among the laity increased, especially among the town's young people. The revival ultimately spread to 25 communities in western Massachusetts and central Connecticut until it began to wane by the spring of 1735.[31]

At a time when Enlightenment rationalism and Arminian theology was popular among some Congregational clergy, Edwards held to traditional Calvinist doctrine. He understood conversion to be the experience of moving from spiritual deadness to joy in the knowledge of one's election (that one had been chosen by God for salvation). While a Christian might have several conversion moments as part of this process, Edwards believed there was a single point in time when God regenerated an individual, even if the exact moment could not be pinpointed.[32]

The Northampton revival featured instances of what critics called enthusiasm but what supporters believed were signs of the Holy Spirit. Services became more emotional and some people had visions and mystical experiences. Edwards cautiously defended these experiences as long as they led individuals to a greater belief in God's glory rather than in self-glorification. Similar experiences would appear in most of the major revivals of the 18th century.[33]

By 1737, George Whitefield had become a national celebrity in England where his preaching drew large crowds, especially in London where the Fetter Lane Society had become a center of evangelical activity.[34] Whitfield joined forces with Edwards to "fan the flame of revival" in the Thirteen Colonies in 1739–40. Soon the First Great Awakening stirred Protestants throughout America.[35]

Conflict soon arose, however, over the issues of itinerant preaching and education requirements for ministers. Evangelicals supported itinerancy and less stringent educational requirements, while their opponents felt that itinerancy was disruptive and preferred ministerial candidates trained at Harvard, Yale or a European university). The growing rift between pro-revival "New Light" and anti-revival "Old Light" factions would divide America's Protestant churches. In the Presbyterian Church, the dispute was known as the Old Side–New Side Controversy.[36]

Evangelical preachers emphasized personal salvation and piety more than ritual and tradition. Pamphlets and printed sermons crisscrossed the Atlantic, encouraging the revivalists.[37] The Awakening resulted from powerful preaching that gave listeners a sense of deep personal revelation of their need of salvation by Jesus Christ. Pulling away from ritual and ceremony, the Great Awakening made Christianity intensely personal to the average person by fostering a deep sense of spiritual conviction and redemption, and by encouraging introspection and a commitment to a new standard of personal morality. It reached people who were already church members. It changed their rituals, their piety and their self-awareness. To the evangelical imperatives of Reformation Protestantism, 18th century American Christians added emphases on divine outpourings of the Holy Spirit and conversions that implanted within new believers an intense love for God. Revivals encapsulated those hallmarks and forwarded the newly created Evangelicalism into the early republic.[38]

19th century

The start of the 19th century saw an increase in missionary work and many of the major missionary societies were founded around this time (see Timeline of Christian missions). Both the evangelical and high church movements sponsored missionaries.

The Second Great Awakening (which actually began in 1790) was primarily an American revivalist movement and resulted in substantial growth of the Methodist and Baptist churches. Charles Grandison Finney was an important preacher of this period.

In the late 19th century, the revivalist Holiness movement, based on the doctrine of "entire sanctification," took a more extreme form in rural America and Canada, where it ultimately broke away from institutional Methodism. In urban Britain the Holiness message was less exclusive and censorious.[39]

John Nelson Darby was a 19th-century Irish Anglican minister who devised modern dispensationalism, an innovative Protestant theological interpretation of the Bible that was incorporated in the development of modern evangelicalism. Cyrus Scofield further promoted the influence of dispensationalism through the explanatory notes to his Scofield Reference Bible. According to scholar Mark S. Sweetnam, who takes a cultural studies perspective, dispensationalism can be defined in terms of its Evangelicalism, its insistence on the literal interpretation of Scripture, its recognition of stages in God's dealings with humanity, its expectation of the imminent return of Christ to rapture His saints, and its focus on both apocalypticism and premillennialism.[40]

In the latter half of the 19th century, Dwight L. Moody of Chicago became a notable evangelical figure. His powerful preaching reached very large audiences.[41][42]

An advanced theological perspective came from the Princeton Theologians from the 1850s to the 1920s, such as Charles Hodge, Archibald Alexander and B.B. Warfield.[43]

20th century

By the 1890s, most American Protestants belonged to evangelical denominations, except for the high church Episcopalians and German Lutherans. In the early 20th century, a divide opened up between the fundamentalists and the mainline Protestant denominations, chiefly over the inerrancy of the Bible. The fundamentalists were those evangelicals who sought to defend their religious traditions, and feared that modern scientific leanings were leading away from the truth. After 1910, evangelicalism was dominated by the fundamentalists, who rejected liberal theology and emphasized the inerrancy of the Scriptures. Evangelicals held the view that the modernist and liberal parties in the Protestant churches had surrendered their heritage as Evangelicals by accommodating the views and values of secularism. At the same time, the modernists criticized fundamentalists for their separatism and their rejection of the Social Gospel. A favored mode of fighting back against liberalism was to prohibit the teaching of Darwinism or macro-evolution as fact in the public schools, a movement that reached its peak in the Scopes Trial of 1925, and resumed in the 1980s. The more modernistic Protestants largely abandoned the term "evangelical" and tolerated evolutionary theories in modern science and even in Biblical studies.

Following the Welsh Methodist revival, the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 began the spread of Pentecostalism in North America.

During and after World War II, evangelicals increasingly organized, and expanded their vision to include the entire world. There was a great expansion of Evangelical activity within the United States, "a revival of revivalism." Youth for Christ was formed; it later became the base for Billy Graham's revivals. At the same time, a split developed between evangelicals, as they disagreed among themselves about how a Christian ought to respond to an unbelieving world. Many evangelicals urged that Christians must engage the culture directly and constructively,[44] and they began to express reservations about being known to the world as fundamentalists. As Kenneth Kantzer put it at the time, the name fundamentalist had become "an embarrassment instead of a badge of honor".[45] The National Association of Evangelicals formed in 1942 as a counterpoise to the mainline Federal Council of Churches. In 1942–43, the Old-Fashioned Revival Hour had a record-setting national radio audience.[46]

The fundamentalists saw the evangelicals as often being too concerned about social acceptance and intellectual respectability, and being too accommodating to a perverse generation that needed correction. In addition, they saw the efforts of evangelist Billy Graham, who worked with non-evangelical denominations, such as the Catholic Church (which they claimed to be heretical), as a mistake. The post-war period also saw growth of the ecumenical movement and the founding of the World Council of Churches, which was generally regarded with suspicion by the evangelical community.

The term neo-evangelicalism was coined by Harold Ockenga in 1947 to identify a distinct movement within self-identified fundamentalist Christianity at the time, especially in the English-speaking world. It described the mood of positivism and non-militancy that characterized that generation. The new generation of evangelicals set as their goal to abandon a militant Bible stance. Instead, they would pursue dialogue, intellectualism, non-judgmentalism, and appeasement. They further called for an increased application of the gospel to the sociological, political, and economic areas. The self-identified fundamentalists also cooperated in separating their "neo-Evangelical" opponents from the fundamentalist name, by increasingly seeking to distinguish themselves from the more open group, whom they often characterized derogatorily by Ockenga's term, "neo-Evangelical" or just evangelical.

More dramatic than the divisions and newfound organization within Evangelicalism was the its expansion of international missionary activity. They had enthusiasm and self-confidence after the national victory in the world war. Many evangelicals came from poor rural districts, but wartime and postwar prosperity dramatically increased the funding resources available for missionary work. While mainline Protestant denominations cut back on their missionary activities, from 7000 to 3000 overseas workers between 1935 and 1980, the evangelicals increased their career foreign missionary force from 12,000 in 1935 to 35,000 in 1980. Meanwhile, Europe was falling behind, as North Americans comprised 41% of all the world's Protestant missionaries in 1936, rising to 52% in 1952 and 72% in 1969. The most active denominations were the Assemblies of God, which nearly tripled from 230 missionaries in 1935 to 626 in 1952, and the United Pentecostal Church International, formed in 1945. The Southern Baptists more than doubled from 405 to 855, as did the Church of the Nazarene from 88 to 200.[47] Overseas missionaries began to prepare for the postwar challenge, most notably the Far Eastern Gospel Crusade (FEGC; now named "Send International"). After Nazi Germany and fascist Japan had been destroyed, the newly mobilized evangelicals were now prepared to combat atheistic communism, secularism, Darwinism, liberalism, Catholicism, and (in overseas missions) paganism.[48]

The Charismatic Movement began in the 1960s and resulted in Pentecostal theology and practice being introduced into many mainline denominations. New Charismatic groups such as the Association of Vineyard Churches and Newfrontiers trace their roots to this period (see also British New Church Movement). The closing years of the 20th century saw controversial postmodern influences entering some parts of evangelicalism, particularly with the emerging church movement.

Interpretation

The Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals states:

There are three senses in which the term "evangelical" is used today at the beginning of the 21st-century. The first is to view "evangelical" as all Christians who affirm a few key doctrines and practical emphases. British historian David Bebbington approaches evangelicalism from this direction and notes four specific hallmarks of evangelical religion: conversionism, the belief that lives need to be changed; activism, the expression of the gospel in effort; biblicism, a particular regard for the Bible; and crucicentrism, a stress on the sacrifice of Christ on the cross.

A second sense is to look at evangelicalism as an organic group of movements and religious tradition. Within this context "evangelical" denotes a style as much as a set of beliefs. As a result, groups such as black Baptists and Dutch Reformed Churches, Mennonites and Pentecostals, Catholic charismatics and Southern Baptists all come under the evangelical umbrella, thus demonstrating just how diverse the movement really is.

A third sense of the term is as the self-ascribed label for a coalition that arose during the Second World War. This group came into being as a reaction against the perceived anti-intellectual, separatist, belligerent nature of the fundamentalist movement in the 1920s and 1930s. Importantly, its core personalities (like Harold John Ockenga and Billy Graham), institutions (for instance, Moody Bible Institute and Wheaton College), and organizations (such as the National Association of Evangelicals and Youth for Christ) have played a pivotal role in giving the wider movement a sense of cohesion that extends beyond these "card-carrying" evangelicals.[49]

John C. Green, a senior fellow at the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, used polling data to separate evangelicals into three broad camps, which he labels as traditionalist, centrist and modernist:[50]

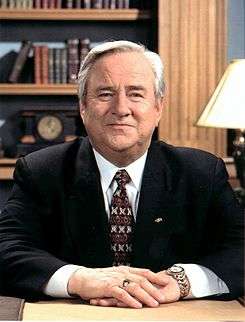

- Traditionalist evangelicals, characterized by high affinity for certain Protestant beliefs, (especially penal substitutionary atonement, justification by faith, the authority of scripture, the priesthood of all believers, etc.) which, when fused with the highly political milieu of Western culture (especially American culture), has resulted in the political disposition that has been labeled the Christian right, with figures like Jerry Falwell and the television evangelist Pat Robertson as its most visible spokesmen.

- Centrist evangelicals, described as socially conservative, mostly avoiding politics, who still support much of traditional Christian theology.

- Modernist evangelicals, a small minority in the movement, have low levels of church-attendance and "have much more diversity in their beliefs".[50]

Demographics

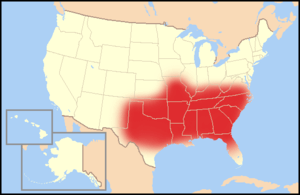

The 2004 survey of religion and politics in the United States identified the evangelical percentage of the population at 26.3 percent while Roman Catholics are 22 percent and mainline Protestants make up 16 percent.[51] In the 2007 Statistical Abstract of the United States, the figures for these same groups are 28.6 percent (evangelical), 24.5 percent (Roman Catholic), and 13.9 percent (mainline Protestant.) The latter figures are based on a 2001 study of the self-described religious identification of the adult population for 1990 and 2001 from the Graduate School and University Center at the City University of New York.[52] A 2008 study showed that in the year 2000 about 9 percent of Americans attended an evangelical service on any given Sunday.[53][54] The Economist estimated in May 2012, that "over one-third of Americans, more than 100 M, can be considered evangelical," arguing that the percentage is often undercounted because many black Christians espouse evangelical theology but prefer to refer to themselves as "born again Christians" rather than "evangelical."[55] These estimated figures given by The Economist agree with those in 2012 from Wheaton College's Institute for the Studies of American Evangelicals.[56]

In 2016 Merritt reported low retention rates among evangelical churches.[57]

The movement is highly diverse and encompasses a vast number of people. Because the group is diverse, not all of them use the same terminology for beliefs. For instance, several recent studies and surveys by sociologists and political scientists that utilize more complex definitional parameters have estimated the number of evangelicals in the U.S. in 2012 at about 30–35% of the population, or roughly between 90 and 100 million people.[56] As of 2017, white evangelicals overall account for about 17% of Americans, while white evangelicals under the age of 30 represent about 8% of Americans in that age group.[58]

The National Association of Evangelicals is a U.S. agency which coordinates cooperative ministry for its member denominations.

Politics

Christian right

Evangelical political influence in America was first evident in the 1830s with movements such as abolition of slavery and the prohibition movement, which closed saloons and taverns in state after state until it succeeded nationally in 1919.[59] The Christian right is a coalition of numerous groups of traditionalist and observant church-goers of every kind: especially Catholics on issues such as birth control and abortion, Southern Baptists, Missouri Synod Lutherans, and others.[60] Since the early 1980s, the Christian right has been associated with several nonprofit political and issue-oriented organizations including the Moral Majority, the Christian Coalition, Focus on the Family and the Family Research Council.[61][62] In the 2016 presidential election, 81% of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump according to exit polls.[63]

Christian left

Evangelical political activists are not all on the right. There is a small group of liberal white Evangelicals.[64] Most African Americans belong to Baptist, Methodist or other denominations that share evangelical beliefs; they are firmly in the Democratic coalition and (with the possible exception of issues involving abortion and homosexuality) are generally liberal in politics.[65]

The evangelical left or progressive evangelicals are Christians aligned with evangelicalism in the United States who generally function on the left wing of the movement, either politically or theologically or both. While the evangelical left is related to the wider Christian left, those who are part of the latter category are not always viewed as evangelical.

Typically, members of the evangelical left affirm the primary tenets of evangelical theology, such as the doctrines of the Incarnation, atonement, and resurrection, and also see the Bible as a primary authority for the Church. Unlike many evangelicals, however, those on the evangelical left support what are often considered progressive or left wing political policies. They are often, for example, opposed to capital punishment and supportive of gun control and welfare programs. In many cases, they are also pacifists. Theologically they also often support and utilize modern biblical criticism, whereas more conservative evangelicals reject it. Some promote the legalization of same-sex marriage or protection of access to abortion for the society at large without necessarily endorsing the practice themselves.

There is considerable dispute over how to even characterize the various segments of the evangelical theological and political spectra, and whether a singular discernible rift between "right" and "left" is oversimplified. However, to the extent that some simplifications are necessary to discuss any complex issue, it is recognized that modern trends like focusing on non-contentious issues (like poverty) and downplaying hot-button social issues (like abortion) tend to be key distinctives of the modern "evangelical left" or "emergent church" movement.

While members of the evangelical left chiefly reside in mainline denominations, they are often heavily influenced by the Anabaptist social tradition.

Recurrent themes

Evolution

Some evangelical Christians strongly dispute the scientifically accepted Neo-Darwinian theory of evolution and have influenced schools to teach Creationism or "Intelligent design" (the position that God or another active intelligence intervened at various points over the course of an otherwise uninterrupted natural evolutionary history to produce the complexity and diversity of life observed on Earth). There have been a variety of court cases over the issue.[66] Young Earth Creationist evangelicals also reject the scientific consensus on the age of the Earth and the cosmos, believing the physical universe to have originated between six and ten thousand years ago, a claim based on a literalistic reading of the first chapters of the Book of Genesis and of other Biblical texts.

Abortion

Since 1980, a central issue motivating conservative evangelicals' political activism is abortion. The 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade by the Supreme Court, which legalized abortion, proved decisive in bringing together Catholics and evangelicals in a political coalition, which became known as the Religious Right when it successfully mobilized its voters behind presidential candidate Ronald Reagan in 1980.[67]

Secularism

In the United States, Supreme Court decisions that outlawed organized prayer in school and restricted church-related schools (for example, preventing them from engaging in racial discrimination while also receiving a tax exemption) also played a role in mobilizing the Religious Right.[68] In addition, questions of sexual morality and homosexuality have been energizing factors—and above all, the notion that "elites" are pushing America into secularism.

Christian nation

Opponents criticise the Evangelicals, whom they say actually want a Christian America—in other words, for America to be a nation in which Christianity is given a privileged position.[69] Survey data shows that "between 64 and 75 percent do not favor a 'Christian Nation' amendment", though between 60 and 75 percent also believe that Christianity and Political Liberalism are incompatible.[70] Evangelical leaders, in turn, counter that they merely seek freedom from the imposition by national elites of an equally subjective secular worldview, and feel that it is their opponents who are violating their rights.[71]

Portrayal in mass media

Many films offer differing views on evangelical, End Times, and Rapture culture. One that offers a revealing view of the mindset of the Calvinist and premillennial dispensationalist element in evangelicalism is Good People Go to Hell, Saved People Go to Heaven.[72]

Other issues

According to recent reports in the New York Times, some evangelicals have sought to expand their movement's social agenda to include poverty, combating AIDS in the Third World, and protecting the environment.[73] This is highly contentious within the evangelical community, since more conservative evangelicals believe that this trend is compromising important issues and prioritizing popularity and consensus too highly. Personifying this division were the evangelical leaders James Dobson and Rick Warren, the former who warned of the dangers of a Barack Obama victory in 2008 from his point of view,[74] in contrast with the latter who declined to endorse either major candidate on the grounds that he wanted the church to be less politically divisive and that he agreed substantially with both men.[75]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 FitzGerald 2017, p. 3.

- ↑ FitzGerald 2017, p. 2.

- ↑ Vickers, Jason E. (7 October 2013). The Cambridge Companion to American Methodism. Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9781107433922.

- ↑ FitzGerald 2017, p. 4-5.

- ↑ FitzGerald 2017, p. 5.

- ↑ Marsden 1991, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ FitzGerald 2017, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ FitzGerald 2017, pp. 8–10.

- ↑ Sweeney 2005, p. 24–25.

- ↑ Balmer 2002, pp. vii–viii.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, p. xiv.

- 1 2 Kidd 2007, p. 12.

- ↑ Youngs 1998, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Youngs 1998, p. 41.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, Chapter 1, Amazon Kindle location 183–184.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, Chapter 1, Amazon Kindle location 186–187.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, Chapter 1, Amazon Kindle location 179.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, Chapter 1, Amazon Kindle location 158.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, Chapter 1, Amazon Kindle location 221–249.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, p. 30.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, p. 37.

- ↑ Lantzer 2012, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Noll 2004, pp. 76.

- ↑ Bebbington 1993, pp. 74.

- ↑ Bebbington 1993, pp. 42.

- ↑ Bebbington 1993, pp. 43.

- 1 2 Kidd 2007, p. 13.

- ↑ Noll 2004, pp. 76-78.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, pp. 13–14,15–16.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Noll 2004, pp. 87, 95.

- ↑ Bebbington 1993, p. 20.

- ↑ Kidd 2007, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Snead, Jennifer (2010), "Print, Predestination, and the Public Sphere: Transatlantic Evangelical Periodicals, 1740–1745", Early American Literature, 45 (1): 93–118, doi:10.1353/eal.0.0092 .

- ↑ Stout, Harold 'Harry' (1991), The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism .

- ↑ Bebbington, David W (1996), "The Holiness Movements in British and Canadian Methodism in the Late Nineteenth Century", Proceedings of the Wesley Historical Society, 50 (6): 203–28 .

- ↑ Sweetnam, Mark S (2010), "Defining Dispensationalism: A Cultural Studies Perspective", Journal of Religious History, 34 (2): 191–212, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.2010.00862.x .

- ↑ Bebbington, David W (2005), Dominance of Evangelicalism: The Age of Spurgeon and Moody

- ↑ Findlay, James F (1969), Dwight L. Moody: American Evangelist, 1837–1899 .

- ↑ Hoffecker, W. Andrew (1981), Piety and the Princeton Theologians, Nutley: Presbyterian & Reformed , v.

- ↑ Henry, Carl FH (August 29, 2003) [1947], The Uneasy Conscience of Modern Fundamentalism (reprint ed.), Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, ISBN 0-8028-2661-X .

- ↑ Zoba, Wendy Murray, The Fundamentalist-Evangelical Split, Belief net, retrieved July 1, 2005 .

- ↑ Carpenter 1999.

- ↑ Carpenter, Joel A (1997), Revive Us Again: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism, pp. 184–5 .

- ↑ Miller-Davenport, Sarah (2013), "'Their blood shall not be shed in vain': American Evangelical Missionaries and the Search for God and Country in Post–World War II Asia", Journal of American History, 99 (4): 1109–32, doi:10.1093/jahist/jas648 .

- ↑ "Defining the Term in Contemporary Context", Defining Evangelicalism, Wheaton College: Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals .

- 1 2 Luo, Michael (April 16, 2006). "Evangelicals Debate the Meaning of 'Evangelical'". The New York Times.

- ↑ Green, John C. "The American Religious Landscape and Political Attitudes: A Baseline for 2004" (PDF) (survey). The Pew forum. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2009.

- ↑ Kosmin, Barry A.; Mayer, Egon; Keysar, Ariela (2001). "American Religious Identification Survey" (PDF). City University of New York; Graduate School and University Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2007. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- ↑ Olson, David T (2008), The American Church in Crisis, Grand Rapids: Zondervan , 240pp.

- ↑ "125 Surprising Facts", The American church (MS PowerPoint) (presentation) .

- ↑ "Lift every voice". The Economist. May 5, 2012.

- 1 2 How Many Evangelicals Are There?, Wheaton College: Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals

- ↑ Carol Howard Merritt (December 30, 2016). "Why Evangelicalism Is Failing A New Generation". The Huffington Post. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ↑ "The evangelical divide". The Economist. October 12, 2017.

- ↑ Clark, Norman H (1976), Deliver Us from Evil: An Interpretation of American Prohibition .

- ↑ "The Triumph of the Religious Right", The Economist November 11, 2004.

- ↑ Himmelstein, Jerome L. (1990), To The Right: The Transformation of American Conservatism, University of California Press .

- ↑ Martin, William (1996), With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America, New York: Broadway Books, ISBN 0-7679-2257-3 .

- ↑ Goldberg, Michelle. "Donald Trump, the Religious Right’s Trojan Horse." New York Times. January 27, 2017. January 27, 2017.

- ↑ Shields, Jon A (2009), The Democratic Virtues of the Christian Right, pp. 117, 121 .

- ↑ Heineman, God is a Conservative, pp 71–2, 173

- ↑ "Ten Major Court Cases about Evolution and Creationism". National Center for Science Education. 2001. ISBN 978-0-385-52526-8. Retrieved March 21, 2015. .

- ↑ Dudley, Jonathan (2011). Broken Words: The Abuse of Science and Faith in American Politics. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-52526-8. Retrieved February 24, 2015. .

- ↑ Heineman, Kenneth J. (1998). God is a Conservative: Religion, Politics and Morality in Contemporary America. pp. 44–123. ISBN 978-0-8147-3554-1.

- ↑ Dershowitz, Alan M (2007), Blasphemy: how the religious right is hijacking our Declaration of Independence, p. 121 .

- ↑ Smith, Christian (2002). Christian America?: What Evangelicals Really Want. p. 207.

- ↑ Limbaugh, David (2003). Persecution: How Liberals are Waging War Against Christians. Regnery. ISBN 0-89526-111-1.

- ↑ "Official website". Good People Go to Hell, Saved People Go to Heaven.

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, David D (October 28, 2007). "The Evangelical Crackup". The New York Times Magazine.

- ↑ "Edge Boss" (PDF). Akamai. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ↑ Vu, Michelle A (July 29, 2008). "Rick Warren: Pastors Shouldn't Endorse Politicians". The Christian Post. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

Bibliography

- Balmer, Randall Herbert (2002), Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism, Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 978-0-664-22409-7, retrieved October 25, 2011 .

- Bauder, Kevin (2011), "Fundamentalism", in Naselli, Andrew; Hansen, Collin, Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-310-55581-0

- Bebbington, David W (1993), Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s, London: Routledge

- Chesnut, R. Andrew (1997), Born Again in Brazil: The Pentecostal Boom and the Pathogens of Poverty, Rutgers University Press .

- Ellingsen, Mark (1991), "Lutheranism", in Dayton, Donald W.; Johnston, Robert K., The Variety of American Evangelicalism, Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press, ISBN 1-57233-158-5

- FitzGerald, Frances (2017). The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 1439131333.

- Himmelstein, Jerome L. (1990), To The Right: The Transformation of American Conservatism, University of California Press .

- Kidd, Thomas S. (2007). The Great Awakening: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America (Amazon Kindle). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11887-2.

- Lantzer, Jason S. (2012). Mainline Christianity: The Past and Future of America's Majority Faith. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5330-9.

- Longfield, Bradley J. (2013), Presbyterians and American Culture: A History, Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press

- Lovelace, Richard F (2007), The American Pietism of Cotton Mather: Origins of American Evangelicalism, Wipf & Stock

- Marsden, George M (1991), Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans, ISBN 0-8028-0539-6

- Martin, William (1996), With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America, New York: Broadway Books, ISBN 0-7679-2257-3

- Mohler, Albert (2011), "Confessional Evangelicalism", in Naselli, Andrew; Hansen, Collin, Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-310-55581-0

- Noll, Mark A. (2004), The Rise of Evangelicalism: The Age of Edwards, Whitefield and the Wesleys, Inter-Varsity, ISBN 1-84474-001-3

- Olson, Roger (2011), "Postconservative Evangelicalism", in Naselli, Andrew; Hansen, Collin, Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-310-55581-0

- Randall, Kelvin (2005), Evangelicals etcetera: conflict and conviction in the Church of England

- Ranger, Terence O, ed. (2008), Evangelical Christianity and Democracy in Africa, Oxford University Press .

- Reimer, Sam (2003). Evangelicals and the Continental Divide: The Conservative Protestant Subculture in Canada and the United States. McGill-Queen's Press.

- Shantz, Douglas H (2013), An Introduction to German Pietism: Protestant Renewal at the Dawn of Modern Europe, JHU

- Stanley, Brian (2013). The Global Diffusion of Evangelicalism: The Age of Billy Graham and John Stott. IVP Academic. ISBN 978-0-8308-2585-1.

- Sutton, Matthew Avery. American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2014). 480 pp. online review

- Sweeney, Douglas A. (2005). The American Evangelical Story: A History of the Movement. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-58558-382-9.

- Tomlinson, Dave (2007). The Post-Evangelical. ISBN 0-310-25385-3.

- Trueman, Carl (2011), The Real Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, Moody Publishers

- Youngs, J. William T. (1998). The Congregationalists. Denominations in America. 4 (Student ed.). Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 9780275964412.

Further reading

- American Evangelicalism and Islam: From the Antichrist to the Mahdi, Germany: Qantara .

- Balmer, Randall Herbert (2004), Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism (excerpt and text search) (2nd ed.) ; online.

- ——— (2010), The Making of Evangelicalism: From Revivalism to Politics and Beyond, ISBN 978-1-60258-243-9 .

- ——— (2000), Blessed Assurance: A History of Evangelicalism in America

- Bastian, Jean-Pierre (1994), Le Protestantisme en Amérique latine: une approche sio-historique [Protestantism in Latin America: a sio‐historical approach], Histoire et société (in French) (27), Genève: Labor et Fides, ISBN 2-8309-0684-5 ; alternative ISBN on back cover, 2-8309-0687-X; 324 pp.

- Beale, David O (1986), In Pursuit of Purity: American Fundamentalism Since 1850, Greenville, SC: Bob Jones University: Unusual, ISBN 0-89084-350-3 .

- Bebbington, D. W. (1989), Evangelicals in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s, London: Unwin .

- Carpenter, Joel A. (1980), "Fundamentalist Institutions and the Rise of Evangelical Protestantism, 1929–1942", Church History, 49: 62–75, doi:10.2307/3164640 .

- ——— (1999), Revive Us Again: The Reawakening of American Fundamentalism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-512907-5 .

- Carter, Heath W. and Laura Rominger Porter, eds. Turning Points in the History of American Evangelicalism (Eerdmans, 2017). xviii, 297 pp

- Chapman, Mark B., "American Evangelical Attitudes Toward Catholicism: Post-World War II to Vatican II," U.S. Catholic Historian, 33#1 (Winter 2015), 25-54.

- Freston, Paul (2004), Evangelicals and Politics in Asia, Africa and Latin America, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-60429-X .

- Griffith, R. M. (2017). Moral combat: how sex divided American Christians and fractured American politics. New York: Basic Books, ISBN 9780465094769. History of sexual politics in the United States, 1920-2017, and how it has influenced the formation of political identities in American Christian denominations.

- Hindmarsh, Bruce (2005), The Evangelical Conversion Narrative: Spiritual Autobiography in Early Modern England, Oxford: Oxford University Press .

- Knox, Ronald (1950), Enthusiasm: a Chapter in the History of Religion, with Special Reference to the XVII and XVIII Centuries, Oxford, Eng: Oxford University Press, pp. viii , 622 pp.

- Luhrmann, Tanya (2012) When God Talks Back-Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God, Knopf

- Marsden, George M (1991), Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism (excerpt and text search) .

- ——— (1987), Reforming Fundamentalism: Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans .

- Menikoff, Aaron (2014). Politics and Piety: Baptist Social Reform in America, 1770-1860. Wipf and Stock Publishers.

- Naselli, A. D., and Collin Hansen, eds (2011), Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. ISBN 9780310293163.

- Noll, Mark A (1992), A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada, Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, pp. 311–89, ISBN 0-8028-0651-1 .

- Noll, Mark A; Bebbington, David W; Rawlyk, George A, eds. (1994), Evangelicalism: Comparative Studies of Popular Protestantism in North America, the British Isles and Beyond, 1700–1990 .

- Pierard, Richard V. (1979), "The Quest For the Historical Evangelicalism: A Bibliographical Excursus", Fides et Historia, 11 (2): 60–72 .

- Price, Robert M. (1986), "Neo-Evangelicals and Scripture: A Forgotten Period of Ferment", Christian Scholars Review, 15 (4): 315–30 .

- Rawlyk, George A; Noll, Mark A, eds. (1993), Amazing Grace: Evangelicalism in Australia, Britain, Canada, and the United States .

- Schafer, Axel R (2011), Countercultural Conservatives: American Evangelicalism From the Postwar Revival to the New Christian Right, U. of Wisconsin Press , 225 pp; covers evangelical politics from the 1940s to the 1990s that examines how a diverse, politically pluralistic movement became, largely, the Christian Right.

- Smith, Timothy L (1957), Revivalism and Social Reform: American Protestantism on the Eve of the Civil War

- Spencer, Michael (March 10, 2009), "The Coming Evangelical Collapse", The Christian Science Monitor .

- Stackhouse, John G (1993), Canadian Evangelicalism in the Twentieth Century

- Sutton, Matthew Avery. American Apocalypse: A history of modern evangelicalism (2014)

- Utzinger, J. Michael (2006), Yet Saints Their Watch Are Keeping: Fundamentalists, Modernists, and the Development of Evangelical Ecclesiology, 1887–1937, Macon: Mercer University Press, ISBN 0-86554-902-8 .

- Ward, WR, Early Evangelicalism: A Global Intellectual History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

- Wigger, John H; Hatch, Nathan O, eds. (2001), Methodism and the Shaping of American Culture (essays by scholars) .

- Wright, Bradley (March 21, 2013), What, exactly, is Evangelical Christianity?, series on Evangelical Christianity in America, Patheos (Black, White and Gray blog)

External links

- Institute for the Study of American Evangelicalism, Wheaton College .

- Operation World – Statistics from around the world including numbers of Evangelicals by country.