Trinity

| Part of a series on |

| God |

|---|

|

In particular religions |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

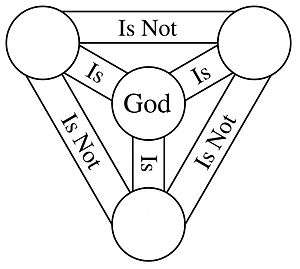

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (Latin: Trinitas, lit. 'triad', from Greek τριάς and τριάδα, from Latin: trinus "threefold")[2] holds that God is one God, but three coeternal consubstantial persons[3] or hypostases[4]—the Father, the Son (Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit—as "one God in three Divine Persons". The three Persons are distinct, yet are one "substance, essence or nature" (homoousios).[5] In this context, a "nature" is what one is, whereas a "person" is who one is.[6][7][8] Sometimes differing views are referred to as nontrinitarian.

According to this central mystery of most Christian faiths, there is only one God in three Persons: while distinct in their relations with each other ("it is the Father who generates, the Son who is begotten, and the Holy Spirit who proceeds"),[9] they are stated to be one in all else, co-equal, co-eternal and consubstantial, and each is God, whole and entire.[10] Accordingly, the whole work of creation and grace in Christianity is seen as a single operation common to all three divine persons, in which each shows forth what is proper to him in the Trinity, so that all things are "from the Father", "through the Son" and "in the Holy Spirit".[11] C.S. Lewis makes the analogy to a cube and its six square faces: God is like the solid mass of the cube, invisible inside it, while the three Persons are like the squares, which are each equally its visible faces.[12]

Trinitarian theologians believe that manifestations of the Trinity are made evident from the very beginning of the Bible. Genesis 1:1-3[13] posits God, His Spirit and the "creative word of God"[14][15] together in the initial Genesis creation narrative account. While the Fathers of the Church saw Old Testament elements such as the appearance of three men to Abraham in Book of Genesis, chapter 18, as foreshadowings of the Trinity, it was the New Testament that they saw as a basis for developing the concept of the Trinity. One of the most influential of the New Testament texts seen as implying the teaching of the Trinity was Matthew 28:19, which mandated baptizing "in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit". Another New Testament text pointing to the Trinity was John 1:1-14, in which the inter-relationships of the Triune God are reflected in the gospel author's description of "the Word", again showing the elements of the Triune God and their eternal (always was, always is, and always shall be) existence. (Revelation 1:8)

Reflection, proclamation, and dialogue led to the formulation of the doctrine that was felt to correspond to the data in the Bible.[16]

While scripture does not contain the word Trinity,[17] an indication of three distinct persons can be found in 1 John 5:7 for the validity of which exist a controversy known as Johannine Comma. Early Christian belief in the deity of Jesus Christ existed since the first century in the writings of John the Apostle (John 1:1, 20:28), Paul the Apostle (Titus 2:13, Romans 9:5, Hebrews 1:8-10), Peter the Apostle (2 Peter 1:1), as well as in the writings of Ignatius of Antioch,[18][19][20][21][22] a disciple of John who was born about the beginning of the Apostolic age (c. 35). Jesus is also quoted as attesting to being one with and equal with the Father, sharing in the glory of the Father before the world began. (John 8:58, 10:30, 17:5).

Romans 8:9-11 implies the interdependency or interrelatedness of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, while examining the redeemed individual, saved by grace, as evidenced by the indwelling Spirit of God.

Subsequently, in the understanding of Trinitarian theology, Scripture "bears witness to" the activity of a God who can only be understood in Trinitarian terms.[23] The doctrine did not take its definitive shape until late in the fourth century.[24] During the intervening period, various tentative solutions, some more and some less satisfactory, were proposed.[25]

Trinitarianism contrasts with positions such as Binitarianism (one deity in two persons, or two deities) and Monarchianism (no pluratity of persons within God), of which Modalistic Monarchianism (one deity revealed in three modes) and Unitarianism (one deity in one person) are subsets. Additionally, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints believes the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost are three separate deities, two of which possess separate bodies of flesh and bones, while the Holy Ghost has only a body of spirit; and that their unity is not physical, but in purpose.[26]

Etymology

The word trinity is derived from Latin trinitas, meaning "the number three, a triad, tri". This abstract noun is formed from the adjective trinus (three each, threefold, triple),[27] as the word unitas is the abstract noun formed from unus (one).

The corresponding word in Greek is tριάς, meaning "a set of three" or "the number three".[28] The first recorded use of this Greek word in Christian theology was by Theophilus of Antioch in about the year 170. He wrote:[29][30]

In like manner also the three days which were before the luminaries, are types of the Trinity [Τριάδος], of God, and His Word, and His wisdom. And the fourth is the type of man, who needs light, that so there may be God, the Word, wisdom, man.[31]

Tertullian, a Latin theologian who wrote in the early 3rd century, is credited as being the first to use the Latin words "Trinity",[32] "person" and "substance"[33] to explain that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are "tres personae, una substantia".[34] While "personae" is often translated as "persons," the Latin word personae is better understood as referring to roles as opposed to individual centers of consciousness.

History

The Ante-Nicene Fathers asserted Christ's deity and spoke of "Father, Son and Holy Spirit", even though their language is not that of the traditional doctrine as formalized in the fourth century. Trinitarians view these as elements of the codified doctrine.[36] Ignatius of Antioch provides early support for the Trinity around 110,[37] exhorting obedience to "Christ, and to the Father, and to the Spirit".[38] Justin Martyr (AD 100–c. 165) also writes, "in the name of God, the Father and Lord of the universe, and of our Saviour Jesus Christ, and of the Holy Spirit".[39] The first of the early church fathers to be recorded using the word "Trinity" was Theophilus of Antioch writing in the late 2nd century. He defines the Trinity as God, His Word (Logos) and His Wisdom (Sophia)[40] in the context of a discussion of the first three days of creation, following the early Christian practice of identifying the Holy Spirit as the Wisdom of God.[41] The first defense of the doctrine of the Trinity was in the early 3rd century by the early church father Tertullian. He explicitly defined the Trinity as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit and defended his theology against "Praxeas",[42] though he noted that the majority of the believers in his day found issue with his doctrine.[32] St. Justin and Clement of Alexandra used the Trinity in their doxologies and St. Basil likewise, in the evening lighting of lamps.[43] Origen of Alexandria (AD 185-c. 253) has often been interpreted as Subordinationist, but some modern researchers have argued that Origen might have actually been anti-Subordinationist.[44][45]

Fourth century theologian Marcellus of Ancyra attributes an earlier formulation of the Trinity to the Gnostic teacher Valentinus (lived c.100 – c.160), whom he identifies as “the first to devise the notion of three subsistent entities (hypostases) . . . in a work that he entitled On the Three Natures," which he says Valentinus "filched from Hermes and Plato." This statement is problematic, however, in that Marcellus was known for launching unsubstantiated attacks against his opponents,[46] and his statements contradict existing evidence. In the work cited by him, On the Three Natures, the three natures are the three natures of mankind, not Deity.[47][48] Likewise, Irenaeus indicates that Valentinus believed in the pre-existent Aeon known as Proarche, Propator, and Bythus who existed alongside Ennœa, and they together begot Monogenes and Aletheia: and these constituted first-begotten Pythagorean Tetrad, from whom thirty Aeons were produced.[49]

Although there is much debate as to whether the beliefs of the Apostles were merely articulated and explained in the Trinitarian Creeds,[50] or were corrupted and replaced with new beliefs,[51][52] all scholars recognize that the Creeds themselves were created in reaction to disagreements over the nature of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. These controversies took some centuries to be resolved.

Of these controversies, the most significant developments were articulated in the first four centuries by the Church Fathers[50] in reaction to Adoptionism, Sabellianism, and Arianism. Adoptionism was the belief that Jesus was an ordinary man, born of Joseph and Mary, who became the Christ and Son of God at his baptism. In 269, the Synods of Antioch condemned Paul of Samosata for his Adoptionist theology, and also condemned the term homoousios (ὁμοούσιος, "of the same being") in the modelist sense in which he used it.[53]

Sabellianism taught that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are essentially one and the same, the difference being simply verbal, describing different aspects or roles of a single being.[54] For this view Sabellius was excommunicated for heresy in Rome c. 220.

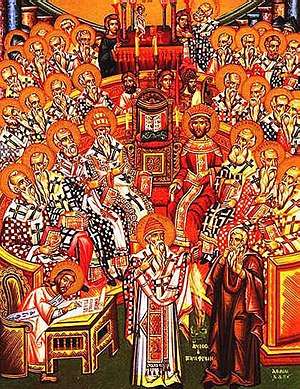

In the fourth century, Arius, as traditionally understood,[note 1] taught that the Father existed prior to the Son who was not, by nature, God but rather a changeable creature who was granted the dignity of becoming "Son of God".[55] In 325, the Council of Nicaea adopted the Nicene Creed which described Christ as "God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father".[56][57] The creed used the term homoousios (of one substance) to define the relationship between the Father and the Son. After more than fifty years of debate, homoousios was recognised as the hallmark of orthodoxy, and was further developed into the formula of "three persons, one being".

The third Council of Sirmium, in 357, was the high point of Arianism. The Seventh Arian Confession (Second Sirmium Confession) held that both homoousios (of one substance) and homoiousios (of similar substance) were unbiblical and that the Father is greater than the Son. (This confession was later known as the Blasphemy of Sirmium)

But since many persons are disturbed by questions concerning what is called in Latin substantia, but in Greek ousia, that is, to make it understood more exactly, as to 'coessential,' or what is called, 'like-in-essence,' there ought to be no mention of any of these at all, nor exposition of them in the Church, for this reason and for this consideration, that in divine Scripture nothing is written about them, and that they are above men's knowledge and above men's understanding;[58]

Athanasius (293–373), who was present at the Council as one of the Bishop of Alexandria's assistants, stated that the bishops were forced to use this terminology,[59] which is not found in Scripture, because the biblical phrases that they would have preferred to use were claimed by the Arians to be capable of being interpreted in what the bishops considered to be a heretical sense.[60] Moreover, the meanings of "ousia" and "hypostasis" overlapped then, so that "hypostasis" for some meant "essence" and for others "person".

The Confession of the Council of Nicaea said little about the Holy Spirit.[61] The doctrine of the divinity and personality of the Holy Spirit was developed by Athanasius in the last decades of his life.[62] He defended and refined the Nicene formula.[61] By the end of the 4th century, under the leadership of Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus (the Cappadocian Fathers), the doctrine had reached substantially its current form.[61]

Gregory of Nazianzus would say of the Trinity, "No sooner do I conceive of the One than I am illumined by the splendour of the Three; no sooner do I distinguish Three than I am carried back into the One. When I think of any of the Three, I think of Him as the Whole, and my eyes are filled, and the greater part of what I am thinking escapes me. I cannot grasp the greatness of that One so as to attribute a greater greatness to the rest. When I contemplate the Three together, I see but one torch, and cannot divide or measure out the undivided light."[63]

Devotion to the Trinity centered in the French monasteries at Tours and Aniane where Saint Benedict dedicated the abbey church to the Trinity in 872.[64] Feast Days were not instituted until 1091 at Cluny and 1162 at Canterbury and papal resistance continued until 1331.[65]

Theology

Trinitarian baptismal formula

In the synoptic Gospels the baptism of Jesus is often interpreted as a manifestation of all three persons of the Trinity: "And when Jesus was baptized, he went up immediately from the water, and behold, the heavens were opened and he saw the spirit of God descending like a dove, and alighting on him; and lo, a voice from heaven, saying, 'This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased.'"[Mt 3:16–17] Baptism is generally conferred with the Trinitarian formula, "in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit".[Mt 28:19] Trinitarians identify this name with the Christian faith into which baptism is an initiation, as seen for example in the statement of Basil the Great (330–379): "We are bound to be baptized in the terms we have received, and to profess faith in the terms in which we have been baptized." The First Council of Constantinople (381) also says, "This is the Faith of our baptism that teaches us to believe in the Name of the Father, of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. According to this Faith there is one Godhead, Power, and Being of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit." Matthew 28:19 may be taken to indicate that baptism was associated with this formula from the earliest decades of the Church's existence.

Oneness Pentecostals demur from the Trinitarian view of baptism and emphasize baptism ‘in the name of Jesus Christ’ as the original apostolic formula.[66] For this reason, they often focus on the baptisms in Acts. Those who place great emphasis on the baptisms in Acts often likewise question the authenticity of Matthew 28:19 in its present form. Most scholars of New Testament textual criticism accept the authenticity of the passage, since there are no variant manuscripts regarding the formula, and the extant form of the passage is attested in the Didache[67] and other patristic works of the 1st and 2nd centuries: Ignatius,[68] Tertullian,[69] Hippolytus,[70] Cyprian,[71] and Gregory Thaumaturgus.[72]

Commenting on Matthew 28:19, Gerhard Kittel states:

This threefold relation [of Father, Son and Spirit] soon found fixed expression in the triadic formulae in 2 Cor. 13:14 and in 1 Cor. 12:4–6. The form is first found in the baptismal formula in Matthew 28:19; Did., 7. 1 and 3....[I]t is self-evident that Father, Son and Spirit are here linked in an indissoluble threefold relationship.[73]

Fundamental monotheism

Christianity, having emerged from Judaism, is a monotheistic religion. According to Baptist theologian Frank Stagg never in the New Testament does the Trinitarian concept become a "tritheism" (three Gods) nor even two.[74] God is one, and that God is a single being is declared in the Bible:

- The Shema of the Hebrew Scriptures: "Hear, O Israel: the LORD our God, the LORD is one."[Deut 6:4]

- The first of the Ten Commandments—"Thou shalt have no other gods before me."[5:7]

- And "Thus saith the LORD the King of Israel and his redeemer the LORD of hosts: I am the first and I am the last; and beside me there is no God."[Isa 44:6]

- In the New Testament: "The LORD our God is one."[Mk 12:29]

In the Trinitarian view, the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit share the one essence, substance or being. The central and crucial affirmation of Christian faith is that there is one savior, God, and one salvation, manifest in Jesus Christ, to which there is access only because of the Holy Spirit. The God of the Old Testament is still the same as the God of the New. In Christianity, statements about a single God are intended to distinguish the Hebraic understanding from the polytheistic view, which see divine power as shared by several beings, beings which can and do disagree and have conflicts with each other.

One God in Three Persons

In Trinitarian doctrine, God exists as three persons or hypostases, but is one being, having a single divine nature.[75] The members of the Trinity are co-equal and co-eternal, one in essence, nature, power, action, and will. As stated in the Athanasian Creed, the Father is uncreated, the Son is uncreated, and the Holy Spirit is uncreated, and all three are eternal without beginning.[76] "The Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit" are not names for different parts of God, but one name for God[77] because three persons exist in God as one entity.[78] They cannot be separate from one another. Each person is understood as having the identical essence or nature, not merely similar natures.[79]

For Trinitarians, emphasis in Genesis 1:26 is on the plurality in the Deity, and in 1:27 on the unity of the divine Essence. A possible interpretation of Genesis 1:26 is that God's relationships in the Trinity are mirrored in man by the ideal relationship between husband and wife, two persons becoming one flesh, as described in Eve's creation later in the next chapter.[2:22]

Perichoresis

Perichoresis (from Greek, "going around", "envelopment") is a term used by some theologians to describe the relationship among the members of the Trinity. The Latin equivalent for this term is circumincessio. This concept refers for its basis to John 14–17, where Jesus is instructing the disciples concerning the meaning of his departure. His going to the Father, he says, is for their sake; so that he might come to them when the "other comforter" is given to them. Then, he says, his disciples will dwell in him, as he dwells in the Father, and the Father dwells in him, and the Father will dwell in them. This is so, according to the theory of perichoresis, because the persons of the Trinity "reciprocally contain one another, so that one permanently envelopes and is permanently enveloped by, the other whom he yet envelopes". (Hilary of Poitiers, Concerning the Trinity 3:1).[80]

Perichoresis effectively excludes the idea that God has parts, but rather is a simple being. It also harmonizes well with the doctrine that the Christian's union with the Son in his humanity brings him into union with one who contains in himself, in the Apostle Paul's words, "all the fullness of deity" and not a part. (See also: Divinization (Christian)). Perichoresis provides an intuitive figure of what this might mean. The Son, the eternal Word, is from all eternity the dwelling place of God; he is the "Father's house", just as the Son dwells in the Father and the Spirit; so that, when the Spirit is "given", then it happens as Jesus said, "I will not leave you as orphans; for I will come to you."[John 14:18]

According to the words of Jesus, married persons are in some sense no longer two but are joined into one. Therefore, Orthodox theologians also see the marriage relationship between a man and a woman to be an example of this sacred union. "Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh." Gen. 2:24. "Wherefore they are no more twain but one flesh. What therefore God hath joined together, let no man put asunder." Matt. 19: 6.[image or "icon" 17:22]

Eternal generation and procession

Trinitarianism affirms that the Son is "begotten" (or "generated") of the Father and that the Spirit "proceeds" from the Father, but the Father is "neither begotten nor proceeds". The argument over whether the Spirit proceeds from the Father alone, or from the Father and the Son, was one of the catalysts of the Great Schism, in this case concerning the Western addition of the Filioque clause to the Nicene Creed. The Roman Catholic Church teaches that, in the sense of the Latin verb procedere (which does not have to indicate ultimate origin and is therefore compatible with proceeding through), but not in that of the Greek verb ἐκπορεύεσθαι (which implies ultimate origin),[81] the Spirit "proceeds" from the Father and the Son, and the Eastern Orthodox Church, which teaches that the Spirit "proceeds" from the Father alone, has made no statement on the claim of a difference in meaning between the two words, one Greek and one Latin, both of which are translated as "proceeds". The Eastern Orthodox Churches object to the Filioque clause on ecclesiological and theological grounds, holding that "from the Father" means "from the Father alone".

This language is often considered difficult because, if used regarding humans or other created things, it would imply time and change; when used here, no beginning, change in being, or process within time is intended and is excluded. The Son is generated ("born" or "begotten"), and the Spirit proceeds, eternally. Augustine of Hippo explains, "Thy years are one day, and Thy day is not daily, but today; because Thy today yields not to tomorrow, for neither does it follow yesterday. Thy today is eternity; therefore Thou begat the Co-eternal, to whom Thou saidst, 'This day have I begotten Thee.'"[Ps 2:7]

Most Protestant groups that use the creed also include the Filioque clause. Its controversial use is addressed in several confessions: the Westminster Confession 2:3, the London Baptist Confession 2:3, and the Lutheran Augsburg Confession 1:1–6.

Economic and immanent Trinity

The term "immanent Trinity" focuses on who God is; the term “economic Trinity” focuses on what God does.

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church,

The Fathers of the Church distinguish between theology (theologia) and economy (oikonomia). "Theology" refers to the mystery of God's inmost life within the Blessed Trinity and "economy" to all the works by which God reveals himself and communicates his life. Through the oikonomia the theologia is revealed to us; but conversely, the theologia illuminates the whole oikonomia. God's works reveal who he is in himself; the mystery of his inmost being enlightens our understanding of all his works. So it is, analogously, among human persons. A person discloses himself in his actions, and the better we know a person, the better we understand his actions.[82]

The ancient Nicene theologians argued that everything the Trinity does is done by Father, Son, and Spirit working in unity with one will. The three persons of the Trinity always work inseparably, for their work is always the work of the one God. The Son's will cannot be different from the Father's because it is the Father's. They have but one will as they have but one being. Otherwise they would not be one God. According to Phillip Cary, if there were relations of command and obedience between the Father and the Son, there would be no Trinity at all but rather three gods.[83] On this point St. Basil observes "When then He says, 'I have not spoken of myself', and again, 'As the Father said unto me, so I speak', and 'The word which ye hear is not mine, but [the Father's] which sent me', and in another place, 'As the Father gave me commandment, even so I do', it is not because He lacks deliberate purpose or power of initiation, nor yet because He has to wait for the preconcerted key-note, that he employs language of this kind. His object is to make it plain that His own will is connected in indissoluble union with the Father. Do not then let us understand by what is called a 'commandment' a peremptory mandate delivered by organs of speech, and giving orders to the Son, as to a subordinate, concerning what He ought to do. Let us rather, in a sense befitting the Godhead, perceive a transmission of will, like the reflexion of an object in a mirror, passing without note of time from Father to Son."[84]

Athanasius of Alexandria explained that the Son is eternally one in being with the Father, temporally and voluntarily subordinate in his incarnate ministry.[85] Such human traits, he argued, were not to be read back into the eternal Trinity. Likewise, the Cappadocian Fathers also insisted there was no economic inequality present within the Trinity. As Basil wrote: "We perceive the operation of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit to be one and the same, in no respect showing differences or variation; from this identity of operation we necessarily infer the unity of nature."[86]

The traditional theory of "appropriation" consists in attributing certain names, qualities, or operations to one of the Persons of the Trinity, not, however, to the exclusion of the others, but in preference to the others. This theory was established by the Latin Fathers of the fourth and fifth centuries, especially by Hilary of Poitiers, Augustine, and Leo the Great. In the Middle Ages, the theory was systematically taught by the Schoolmen such as Bonaventure.[87]

Trinity and love

Augustine "coupled the doctrine of the Trinity with anthropology. Proceeding from the idea that humans are created by God according to the divine image, he attempted to explain the mystery of the Trinity by uncovering traces of the Trinity in the human personality".[88] The first key of his exegesis is an interpersonal analogy of mutual love. In De trinitate (399 — 419) he wrote,

"We are now eager to see whether that most excellent love is proper to the Holy Spirit, and if it is not so, whether the Father, or the Son, or the Holy Trinity itself is love, since we cannot contradict the most certain faith and the most weighty authority of Scripture which says: 'God is love'".[89][90]

The Bible reveals it although only in the two neighboring verses 1 John 4:8;16, therefore one must ask if love itself is triune. Augustine found that it is, and consists of "three: the lover, the beloved, and the love."[91][92]

In the "Preface to the Second Edition" of his 1970 German book Theologie der Drei Tage (English translation: Mysterium Paschale), Hans Urs von Balthasar takes a cue from Revelation 13:8[93] (Vulgate: agni qui occisus est ab origine mundi, NIV: "the Lamb who was slain from the creation of the world") to explore the "God is love" idea as an "eternal super-kenosis".[94][95]

The underlying question is if the three Persons of the Trinity can live a self-love (amor sui), as well as if for them, with the conciliar dogmatic formulation in terms that today we would call ontotheological, it is possible that the aseity (causa sui) is valid. If the Father is not the Son or the Spirit since the generator/begetter is not the generated/begotten nor the generation/generative process and vice versa, and since the lover is neither the beloved nor the love dynamic between them and vice versa, Christianity has provided as a response a concept of divine ontology and love different from common sense (omnipotence, omnibenevolence, impassibility, etc.):[96] a sacrificial, martyring, crucifying, precisely kenotic concept.

1946 Kitamori's Theology of the Pain of God[97] and 1971 Moltmann's The Crucified God[98] are two 1900s books that have taken up the ancient theological idea of theopaschism, i.e. that at least unus de Trinitate passus est.[99] In the words of Balthasar himself: "At this point, where the subject undergoing the 'hour' is the Son speaking with the Father, the controversial 'Theopaschist formula' has its proper place: 'One of the Trinity has suffered.' The formula can already be found in Gregory Nazianzen: 'We needed a...crucified God'."[100]

As we will see in the next section, the same problem also arises in terms of the will between the commander/normer/legislator, commanded/normed/legislated and the process between them: is each Trinity's Person lex sui or not?

Trinity and will

Roger E. Olson says that a number of evangelical theologians hold the view that there is a hierarchy of authority in the Trinity with the Son being subordinate to the Father. "The Gospel of John makes this clear as Jesus repeatedly mentions that he came to do the Father's will."[101] Olsen cautions, however, that the hierarchy in the "economic Trinity" should be distinguished from the "immanent Trinity". He cites the Cappadocian Fathers, "the Father is the source or "fount" of divinity within the Godhead; the Son and the Spirit derive their deity from the Father eternally (so there is no question of inequality of being). Their favorite analogy was the sun and its light and heat. There is no imagining the sun without its light and heat and yet it is the source of them."[101]

Benjamin B. Warfield saw a principle of subordination in the "modes of operation" of the Trinity, but was also hesitant to ascribe the same to the "modes of subsistence" in relation of one to another. While noting that it is natural to see a subordination in function as reflecting a similar subordination in substance, he suggests that this might be the result of "...an agreement by Persons of the Trinity – a "Covenant" as it is technically called – by virtue of which a distinct function in the work of redemption is assumed by each".[102]

Political aspect

Richard E. Rubenstein says that Emperor Constantine and his advisor Hosius of Corduba were aware of the usefulness of having a divinely ordained church in which the church authority, and not the individual, was able to determine individual salvation, and threw their support toward the homoousion Nicene formula.[103] According to Eusebius, Constantine suggested the term homoousios at the Council of Nicaea, though most scholars have doubted that Constantine had such knowledge and have thought that most likely Hosius had suggested the term to him.[104] Constantine later changed his view about the Arians, who opposed the Nicene formula, and supported the bishops who rejected the formula,[105] as did several of his successors, the first emperor to be baptized in the Nicene faith being Theodosius the Great, emperor from 379 to 395.[106]

Biblical background

From the Old Testament, the early church retained the conviction that God is one.[107] The New Testament does not use the word Τριάς (Trinity)[108] nor explicitly teach the Nicene Trinitarian doctrine, but it contains several passages that use twofold and threefold patterns to speak of God. Binitarian passages include Rom. 8:11, 2 Cor. 4:14, Galatians 1:1, Eph. 1:20, 1 Tim. 1:2, 1 Pet. 1:21, and 2 John 1:13. Passages which refer to the Godhead with a threefold pattern include Matt. 28:19, 1 Cor. 6:11 and 12:4ff., Gal. 3:11–14, Heb. 10:29, 1 Pet. 1:2 and 1 John 5:7. These passages provided the material with which Christians would develop doctrines of the Trinity.[107] Reflection by early Christians on passages such as the Great Commission: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit"[Matt 28:19] and Paul the Apostle's blessing: "The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all",[2 Cor. 13:14] while at the same time the Jewish Shema Yisrael: "Hear, O Israel: The Lord is our God, the Lord alone."[Deuteronomy 6:4][109] has led some Christians to question how the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are "one". Eventually, the diverse references to God, Jesus, and the Spirit found in the New Testament were brought together to form the doctrine of the Trinity—one God subsisting in three persons and one substance. The doctrine of the Trinity was used to combat heretical tendencies of how the three are related and to defend the church against charges of worshiping two or three gods.[110]

Some scholars dispute the idea that support for the Trinity can be found in the Bible, and argue that the doctrine is the result of theological interpretations rather than sound exegesis of scripture.[111][112]

According to The New Encyclopædia Britannica: "Neither the word Trinity nor the explicit doctrine appears in the New Testament."

In order to articulate the dogma of the Trinity, the Church had to develop her own terminology with the help of certain notions of philosophical origin.

— Catechism of the Catholic Church.

The Christian Bible, including the New Testament, has no trinitarian statements or speculations concerning a trinitary deity.

— Encyclopædia Britannica.

Dominican priest Marie-Émile Boismard wrote in his book À l'aube du christianisme—La naissance des dogmes (At the Dawn of Christianity—The Birth of Dogmas): "The statement that there are three persons in the one God . . . cannot be read anywhere in the New Testament."

The impression could arise that the Trinitarian dogma is in the last analysis a late 4th-century invention. In a sense, this is true . . . The formulation 'one God in three Persons' was not solidly established, certainly not fully assimilated into Christian life and its profession of faith, prior to the end of the 4th century.

— New Catholic Encyclopedia (1967), Volume 14, page 299.

The Encyclopedia Americana says: "Fourth century Trinitarianism did not reflect accurately early Christian teaching regarding the nature of God; it was, on the contrary, a deviation from this teaching."

The doctrine of the trinity . . . is not a product of the earliest Christian period, and we do not find it carefully expressed before the end of the second century.

— Library of Early Christianity—Gods and the One God.

The concept was expressed in early writings from the beginning of the 2nd century forward, and other scholars hold that the way the New Testament repeatedly speaks of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit is such as to require one to accept a Trinitarian understanding.[74]

The Comma Johanneum, 1 John 5:7, is a disputed text which states: "For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one." However, this passage is not considered to be part of the genuine text,[113] and most scholars agree that the phrase was a gloss.[114]

Jesus as God

The expression 'Jesus is God' is not same as 'Jesus as God' as in an example, "Jesus is worshiped as God".

The Gospel of John has been seen as especially aimed at emphasizing Jesus' divinity, presenting Jesus as the Logos, pre-existent and divine, from its first words: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God."[John 1:1][115] The Gospel of John ends with Thomas's declaration that he believed Jesus was God, "My Lord and my God!"[John 20:28][110] There is no significant tendency among modern scholars to deny that John 1:1 and John 20:28 identify Jesus with God.[116] John also portrays Jesus as the agent of creation of the universe.[117]

There are also a few possible biblical supports for the divinity of Jesus found in the Synoptic Gospels. The Gospel of Matthew, for example, quotes Jesus as saying, "All things have been handed over to me by my Father."[Mt 11:27] This is similar to John, who wrote that Jesus said, "All that the Father has is mine."[John 16:15] These verses have been quoted to defend the omnipotence of Christ, having all power, as well as the omniscience of Christ, having all wisdom.

Expressions also in the Pauline epistles have been interpreted as attributing divinity to Jesus. They include: "For by him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things were created by him and for him"[Colossians 1:16] and "For in Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form",[Colossians 2:9] and in Paul the Apostle's claim to have been "sent not from men nor by man, but by Jesus Christ and God the Father".[Galatians 1:1][118]

Some have suggested that John presents a hierarchy when he quotes Jesus as saying, "The Father is greater than I",[14:28] a statement which was appealed to by nontrinitarian groups such as Arianism.[119] However, Church Fathers such as Augustine of Hippo argued this statement was to be understood as Jesus speaking in as to his human nature.[120]

Holy Spirit as God

As the Arian controversy was dissipating, the debate moved from the deity of Jesus Christ to the equality of the Holy Spirit with the Father and Son. On one hand, the Pneumatomachi sect declared that the Holy Spirit was an inferior person to the Father and Son. On the other hand, the Cappadocian Fathers argued that the Holy Spirit was an equal person to the Father and Son.

Although the main text used in defense of the deity of the Holy Spirit was Matthew 28:19, Cappadocian Fathers such as Basil the Great argued from other verses such as "But Peter said, 'Ananias, why has Satan filled your heart to lie to the Holy Spirit and to keep back for yourself part of the proceeds of the land? While it remained unsold, did it not remain your own? And after it was sold, was it not at your disposal? Why is it that you have contrived this deed in your heart? You have not lied to men but to God.'"[Acts 5:3–4][121]

Another passage the Cappadocian Fathers quoted from was "By the word of the Lord the heavens were made, and by the breath of his mouth all their host."[Psalm 33:6] According to their understanding, because "breath" and "spirit" in Hebrew are both "רוּחַ" ("ruach"), Psalm 33:6 is revealing the roles of the Son and Holy Spirit as co-creators. And since, according to them,[121] because only the holy God can create holy beings such as the angels, the Son and Holy Spirit must be God.

Yet another argument from the Cappadocian Fathers to prove that the Holy Spirit is of the same nature as the Father and Son comes from "For who knows a person's thoughts except the spirit of that person, which is in him? So also no one comprehends the thoughts of God except the Spirit of God."[1Cor. 2:11] They reasoned that this passage proves that the Holy Spirit has the same relationship to God as the spirit within us has to us.[121]

The Cappadocian Fathers also quoted, "Do you not know that you are God's temple and that God's Spirit dwells in you?"[1Cor. 3:16] and reasoned that it would be blasphemous for an inferior being to take up residence in a temple of God, thus proving that the Holy Spirit is equal with the Father and the Son.[122]

They also combined "the servant does not know what his master is doing"[John 15:15] with 1 Corinthians 2:11 in an attempt to show that the Holy Spirit is not the slave of God, and therefore his equal.[123]

The Pneumatomachi contradicted the Cappadocian Fathers by quoting, "Are they not all ministering spirits sent out to serve for the sake of those who are to inherit salvation?"[Hebrews 1:14] in effect arguing that the Holy Spirit is no different from other created angelic spirits.[124] The Church Fathers disagreed, saying that the Holy Spirit is greater than the angels, since the Holy Spirit is the one who grants the foreknowledge for prophecy[1Cor. 12:8–10] so that the angels could announce events to come.[121]

The usage of the word "paraclete" (Greek: parakletos) for the Holy Spirit in John 14:16, which can be translated as advocate, intercessor, counsellor or protector,[125] and the Holy Spirit's essence and action characterized by truth, as all three persons of the Trinity are linked with truth (see v. 17),[126] are seen as arguments that he is a divine person; especially that Jesus calls him another counsellor, in this way expressing that the Holy Spirit is similar to himself in regard to our counsel.[127]

Old Testament parallels

In addition, the Old Testament has also been interpreted as foreshadowing the Trinity,[128] by referring to God's word,[Ps 33:6] his spirit,[Isa 61:1] and Wisdom,[Prov 9:1] as well as narratives such as the appearance of the three men to Abraham.[Gen 18][129] However, it is generally agreed among Trinitarian Christian scholars that it would go beyond the intention and spirit of the Old Testament to correlate these notions directly with later Trinitarian doctrine.[130][131]

Some Church Fathers believed that a knowledge of the mystery was granted to the prophets and saints of the Old Testament, and that they identified the divine messenger of Genesis 16:7,21:17, 31:11, Exodus 3:2 and Wisdom of the sapiential books with the Son, and "the spirit of the Lord" with the Holy Spirit.[130] Other Church Fathers, such as Gregory Nazianzen, argued in his Orations that the revelation was gradual, claiming that the Father was proclaimed in the Old Testament openly, but the Son only obscurely, because "it was not safe, when the Godhead of the Father was not yet acknowledged, plainly to proclaim the Son".[132]

Genesis 18–19 has been interpreted by Christians as a Trinitarian text.[133] The narrative has the Lord appearing to Abraham, who was visited by three men.[Gen 18:1–2] Then in Genesis 19, "the two angels" visited Lot at Sodom. The interplay between Abraham on the one hand and the Lord/three men/the two angels on the other was an intriguing text for those who believed in a single God in three persons. Justin Martyr, and John Calvin similarly, interpreted it such that Abraham was visited by God, who was accompanied by two angels.[134] Justin supposed that the God who visited Abraham was distinguishable from the God who remains in the heavens, but was nevertheless identified as the (monotheistic) God. Justin appropriated the God who visited Abraham to Jesus, the second person of the Trinity.

Augustine, in contrast, held that the three visitors to Abraham were the three persons of the Trinity.[134] He saw no indication that the visitors were unequal, as would be the case in Justin's reading. Then in Genesis 19, two of the visitors were addressed by Lot in the singular: "Lot said to them, 'Not so, my lord.'"[Gen 19:18 KJV][134] Augustine saw that Lot could address them as one because they had a single substance, despite the plurality of persons.[note 2]

According to Swedenborg, the three angels which appeared to Abraham do represent the Trinity, but a Trinity of one being: the Divine Itself, the Divine Human and the Divine Proceeding. That one being is represented is indicated by the fact that they are referred to in the singular as Jehovah and Lord.[135] The reason why only two of the angels went to visit Sodom and Gomorrah is that they represent the Divine Human and the Divine Proceeding, and to those aspects of the Divine belongs judgment, as Jesus declared that all judgment was entrusted by the Father to the Son.[John 5:22][136] The three angels did indeed appear to Abraham as three men, but they are only a symbolic representation of the Trinity, which should not be taken literally as three distinct persons. In the Old Testament, Swedenborg finds the earliest direct reference to a Trine in the Divinity in the account of Moses' encounter with the Lord in Exodus which states, "And Jehovah passed by upon his face, and called, Jehovah, Jehovah, a God merciful and gracious."[Exodus 34:6][137]

Some Christians interpret the theophanies or appearances of the Angel of the Lord as revelations of a person distinct from God, who is nonetheless called God.[138] This interpretation is found in Christianity as early as Justin Martyr and Melito of Sardis, and reflects ideas that were already present in Philo.[139] The Old Testament theophanies were thus seen as Christophanies, each a "preincarnate appearance of the Messiah".[140]

Impact of Stoic philosophy

In the introduction to his 1964 translation of Meditations,[141] the Anglican priest Maxwell Staniforth discussed the profound influence of Stoic philosophy on Christianity. In particular:

Again in the doctrine of the Trinity, the ecclesiastical conception of Father, Word, and Spirit finds its germ in the different Stoic names of the Divine Unity. Thus Seneca, writing of the supreme Power which shapes the universe, states, 'This Power we sometimes call the All-ruling God, sometimes the incorporeal Wisdom, sometimes the holy Spirit, sometimes Destiny.' The Church had only to reject the last of these terms to arrive at its own acceptable definition of the Divine Nature; while the further assertion 'these three are One', which the modern mind finds paradoxical, was no more than commonplace to those familiar with Stoic notions.

Artistic depictions

The Trinity is most commonly seen in Christian art with the Spirit represented by a dove, as specified in the Gospel accounts of the Baptism of Christ; he is nearly always shown with wings outspread. However depictions using three human figures appear occasionally in most periods of art.[142]

The Father and the Son are usually differentiated by age, and later by dress, but this too is not always the case. The usual depiction of the Father as an older man with a white beard may derive from the biblical Ancient of Days, which is often cited in defense of this sometimes controversial representation. However, in Eastern Orthodoxy the Ancient of Days is usually understood to be God the Son, not God the Father (see below)—early Byzantine images show Christ as the Ancient of Days,[143] but this iconography became rare. When the Father is depicted in art, he is sometimes shown with a halo shaped like an equilateral triangle, instead of a circle. The Son is often shown at the Father's right hand.[Acts 7:56] He may be represented by a symbol—typically the Lamb (agnus dei) or a cross—or on a crucifix, so that the Father is the only human figure shown at full size. In early medieval art, the Father may be represented by a hand appearing from a cloud in a blessing gesture, for example in scenes of the Baptism of Christ. Later, in the West, the Throne of Mercy (or "Throne of Grace") became a common depiction. In this style, the Father (sometimes seated on a throne) is shown supporting either a crucifix[144] or, later, a slumped crucified Son, similar to the Pietà (this type is distinguished in German as the Not Gottes)[145] in his outstretched arms, while the Dove hovers above or in between them. This subject continued to be popular until the 18th century at least.

By the end of the 15th century, larger representations, other than the Throne of Mercy, became effectively standardised, showing an older figure in plain robes for the Father, Christ with his torso partly bare to display the wounds of his Passion, and the dove above or around them. In earlier representations both Father, especially, and Son often wear elaborate robes and crowns. Sometimes the Father alone wears a crown, or even a papal tiara.

In the later part of the Christian Era, in Renaissance European iconography, the Eye of Providence began to be used as an explicit image of the Christian Trinity and associated with the concept of Divine Providence. Seventeenth-century depictions of the Eye of Providence sometimes show it surrounded by clouds or sunbursts.[146]

Image gallery

Depiction of Trinity from Saint Denis Basilica in Paris (12th century)

Depiction of Trinity from Saint Denis Basilica in Paris (12th century)_God%2C_The_Holy_Spirit%2C_and_Christ_Crucified.jpg) Father, The Holy Spirit, and Christ Crucified, depicted in a Welsh manuscript. c. 1390–1400

Father, The Holy Spirit, and Christ Crucified, depicted in a Welsh manuscript. c. 1390–1400 The Holy Trinity in an angelic glory over a landscape, by Lucas Cranach the Elder (d. 1553)

The Holy Trinity in an angelic glory over a landscape, by Lucas Cranach the Elder (d. 1553)- God the Father (top), and the Holy Spirit (represented by a dove) depicted above Jesus. Painting by Francesco Albani (d. 1660)

God the Father (top), the Holy Spirit (a dove), and child Jesus, painting by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (d. 1682)

God the Father (top), the Holy Spirit (a dove), and child Jesus, painting by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (d. 1682) Pope Clement I prays to the Trinity, in a typical post-Renaissance depiction by Gianbattista Tiepolo (d. 1770)

Pope Clement I prays to the Trinity, in a typical post-Renaissance depiction by Gianbattista Tiepolo (d. 1770) Atypical depiction. The Son is identified by a lamb, the Father an Eye of Providence, and the Spirit a dove, painting by Fridolin Leiber (d. 1912)

Atypical depiction. The Son is identified by a lamb, the Father an Eye of Providence, and the Spirit a dove, painting by Fridolin Leiber (d. 1912).jpg) 13th-century depiction of the Trinity from a Roman de la Rose manuscript

13th-century depiction of the Trinity from a Roman de la Rose manuscript A Christian version of the Eye of Providence, emphasizing the triangle representing the Trinity

A Christian version of the Eye of Providence, emphasizing the triangle representing the Trinity

Nontrinitarianism

Nontrinitarianism (or antitrinitarianism) refers to Christian belief systems that reject the doctrine of the Trinity as found in the Nicene Creed as not having a scriptural origin. Nontrinitarian views differ widely on the nature of God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit. Various nontrinitarian views, such as Adoptionism, Monarchianism and Arianism existed prior to the formal definition of the Trinity doctrine in AD 325, 360, and 431, at the Councils of Nicaea, Constantinople, and Ephesus, respectively.[147] Following the final victory of orthodoxy at Constantinople in 381, Arianism was driven from the Empire, retaining a foothold amongst the Teutonic tribes. When the Franks converted to Catholicism in 496, however, it gradually faded out.[148] Nontrinitarianism was later renewed in the Gnosticism of the Cathars in the 11th through 13th centuries, in the Age of Enlightenment of the 18th century, and in some groups arising during the Second Great Awakening of the 19th century. Also binitarianism.

Modern nontrinitarian groups or denominations include Christadelphians, Christian Scientists, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Dawn Bible Students, Friends General Conference, Iglesia ni Cristo, Jehovah's Witnesses, Living Church of God, Oneness Pentecostals, the Seventh Day Church of God, Unitarian Universalist Christians, United Church of God, The Shepherd's Chapel and Spiritism.

Islamic views

Islam considers Jesus to be a prophet, but not divine,[149] and Allah to be absolutely indivisible (a concept known as tawhid).[150] Several verses of the Qur'an state that the doctrine of the Trinity is blasphemous.[151][152]

"Say: He is God, the One and Only; God, the Eternal, Absolute; He begetteth not, nor is He begotten; And there is none like unto Him.

Certainly they disbelieve who say: Surely Allah is the third (person) of the three; and there is no god but the one Allah, and if they desist not from what they say, a painful chastisement shall befall those among them who disbelieve.

And when Allah will say: O Isa son of Marium! did you say to men, Take me and my mother for two gods besides Allah he will say: Glory be to Thee, it did not befit me that I should say what I had no right to (say); if I had said it, Thou wouldst indeed have known it; Thou knowest what is in my mind, and I do not know what is in Thy mind, surely Thou art the great Knower of the unseen things.

Interpretation of these verses by modern scholars has been varied.[156][157] Verse 5:73 has been interpreted as a potential criticism of Syriac literature that references Jesus as "the third of three" and thus an attack on the view that Christ was divine.[158]

Edward Hulmes writes:

"The Qur'anic interpretation of trinitarian orthodoxy as belief in the Father, the Son, and the Virgin Mary, may owe less to a misunderstanding of the New Testament itself than to a recognition of the role accorded by local Christians (see Choloridians) to Mary as mother in a special sense."[159]

There is also debate about whether this verse should be taken literally.[160] For example, Thomas states that verse 5:116 need not be seen as describing actually professed beliefs, but rather, giving examples of shirk (claiming divinity for beings other than God) and a "warning against excessive devotion to Jesus and extravagant veneration of Mary, a reminder linked to the central theme of the Qur'an that there is only one God and He alone is to be worshipped."[156] When read in this light, it can be understood as an admonition, "Against the divinization of Jesus that is given elsewhere in the Qur'an and a warning against the virtual divinization of Mary in the declaration of the fifth-century church councils that she is 'God-bearer'."[156]

Judaism

Judaism traditionally maintains a tradition of monotheism to the exclusion of the possibility of a Trinity.[149] In Judaism, God is understood to be the absolute one, indivisible, and incomparable being who is the ultimate cause of all existence. The idea of God as a duality or trinity is heretical — it is even considered by some polytheistic.[161]

See also

- Ayyavazhi Trinity

- Social trinitarianism

- Three Pure Ones

- Thomas F. Torrance, contemporary theologian

- Trikaya, the three Buddha bodies

- Trimurti

- Trinitarian Order

- Trinitarian universalism

- Trinity Sunday, a day to celebrate the doctrine

- Triple deity, an associated term in Comparative religion

Extended notes

- ↑ Very little of Arius' own writings have survived. We depend largely on quotations made by opponents which reflect what they thought he was saying. Furthermore, there was no single Arian party or agenda but rather various critics of the Nicene formula working from distinct perspectives.(see Williams, Rowan. Arius SPCK (2nd edn, 2001) p.95ff & pp.247ff)

- ↑ Augustine had poor knowledge of the Greek language, and no knowledge of Hebrew. So he trusted the LXX Septuagint, which differentiates between κύριοι[Gen 19:2] ('lords', vocative plural) andκύριε[Gen 19:18] ('lord', vocative singular), even if the Hebrew verbal form,נא-אדני (na-adoni), is exactly the same in both cases.

Endnotes and references

- ↑ The Heavenly and Earthly Trinities on the site of the National Gallery in London.

- ↑ "Definition of trinity in English". Oxford Dictionaries - English.

- ↑ The Family Bible Encyclopedia (1972). p. 3790.

- ↑ See Geddes, Leonard (1911). "Person". In Herbermann, Charles. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

- ↑ Definition of the Fourth Lateran Council quoted in Catechism of the Catholic Church §253.

- ↑ "Frank Sheed, ''Theology and Sanity''". Ignatiusinsight.com. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ "Understanding the Trinity". Credoindeum.org. 16 May 2012. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 16 Aug 2016.

- ↑ "Baltimore Catechism, No. 1, Lesson 7". Quizlet.com. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Fourth Council of the Lateran, CCC §254; Latin: Est Pater, qui generat, et Filius, qui gignitur, et Spiritus Sanctus, qui procedit (DS 804).

- ↑ Coppens, Charles, S.J. (1903). A Systematic Study of the Catholic Religion. St. Louis: B. HERDER. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ↑ CCC §253–267: "The dogma of the Holy Trinity".

- ↑ Lewis, C.S. (1952). Mere Christianity. pp. 88, Ch IV.2 The Three-Personal God.

- ↑ "Genesis 1:1-3". Biblia.com. Faithlife. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ↑ Younker, Randall W. "Crucial Questions of Interpretation in Genesis 1" (PDF). Biblical Research Institute. Biblical Research Institute General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ↑ "John 1:1-4". Biblia.com. Faithlife. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ↑ "Trinity, doctrine of" in The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-192-80290-3)

- ↑ "Trinity word not in Scripture". carm.org. 24 November 2008.

- ↑ Ignatius, To the Ephesians, 1, 7, 18, 19

- ↑ Ignatius, To Polycarp, 3, 8

- ↑ Ignatius, To the Smyrnaeans, 10

- ↑ Ignatius, To the Romans, 6

- ↑ Ignatius, To the Magnesians, 8

- ↑ McGrath Alister E. Christian Theology: An Introduction Blackwell, Oxford (2001) p.321

- ↑ McGrath, Alister E. Christian Theology: An Introduction Blackwell, Oxford (2001) p.324

- ↑ Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Doctrines A & G Black (1965) p. 88

- ↑ "Godhead". www.mormon.org. Retrieved 2017-01-15.

- ↑ "Lewis and Short: ''trinus''". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Liddell & Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon. entry for Τριάς, retrieved 19 December 2006

- ↑ Theophilus of Antioch, To Autolycus, II.XV (retrieved on 19 December 2006).

- ↑ W.Fulton in the "Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics"

- ↑ Aboud, Ibrahim (Fall 2005). Theandros an online Journal of Orthodox Christian Theology and Philosophy. 3, number 1. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008.

- 1 2 "Against Praxeas, chapter 3". Ccel.org. 1 June 2005. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ↑ Against Praxeas, chapter 2 and in other chapters

- ↑ History of the Doctrine of the Trinity. Accessed 15 September 2007.

- ↑ See Elizabeth Lev, "Dimming the Pauline Spotlight; Jubilee Fruits", 2009 Archived 14 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Orthodox Outlet for Dogmatic Enquiries: On God". Oodegr.com. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History iii.36

- ↑ "St. Ignatius of Antioch to the Magnesians (Shorter Recension), Roberts-Donaldson translation". Earlychristianwritings.com. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ "First Apology, LXI". Ccel.org. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ Theophilus, Apologia ad Autolycum, Book II, Chapter 15

- ↑ Theophilus, To Autolycus, 1.7 Cf. Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 4.20.1, 3; Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching, 5

- ↑ Tertullian Against Praxeas

- ↑ Mulhern, Philip F. (1967) "Trinity, Holy, Devotion", in New Catholic encyclopedia. Prepared by an editorial staff at the Catholic University of America. New York:McGraw-Hill, 14. 306

- ↑ Ramelli, Llaria. "Origen's Anti-Subordinationism and Its Heritage in the Nicene and Cappadocian Line". Brill. JSTOR 41062535.

- ↑ Barnard, L.W. "The Antecedents of Arius". JSTOR 1583070.

- ↑ See Eusebius, Contra Marcellum, Book 1

- ↑ The Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Edition. Valentinus. Cambridge. 1911. p. 854.

- ↑ Concerning this, Irenaeus writes, "They conceive, then, of three kinds of men, spiritual, material, and animal, represented by Cain, Abel, and Seth. These three natures are no longer found in one person, but constitute various kinds [of men]. The material goes, as a matter of course, into corruption." (Against Heresies, 1.7.5)

- ↑ Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 1.1.1-3

- 1 2 Bingham, Jeffrey, "HT200 Class Notes", Dallas Theological Seminary, (2004).

- ↑ The Encyclopedia Americana (1956), Vol. XXVII, p. 294L

- ↑ Nouveau Dictionnaire Universel (Paris, 1865–1870), Vol. 2, p. 1467.

- ↑ "Catholic Encyclopedia: article:''Paul of Samosata''". Newadvent.org. 1 February 1911. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Chadwick, Henry. The Early Church Pelican/Penguin (1967) p.87

- ↑ "Arianism" in Cross, F.L. & Livingstone, E.A. (eds) The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (1974)

- ↑ "Creeds of Christendom, with a History and Critical notes. Volume I. The History of Creeds. - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org.

- ↑ Anderson, Michael. "The Nicaeno-Constantinopolitan Creed". www.creeds.net.

- ↑ "Second Creed of Sirmium or "The Blasphemy of Sirmium"". www.fourthcentury.com. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- ↑ "Athanasius, Bishop of Alexanria, Theologian, Doctor". Justus.anglican.org. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ "Athanasius: De Decretis or Defence of the Nicene Definition, Introduction, 19". Tertullian.org. 6 August 2004. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Trinity". Britannica Encyclopaedia of World Religions. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006.

- ↑ On Athanasius, Oxford Classical Dictionary, Edited by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth. Third edition. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- ↑ Gregory of Nazianzus, Orations 40.41

- ↑ Mulhern, 306.

- ↑ Mulhern, p.306

- ↑ Wolfgang Vondey, Pentecostalism, A Guide for the Perplexed (London; New Delhi; New York; Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2013), 78.

- ↑ 7:1, 3 online

- ↑ Epistle to the Philippians, 2:13 online

- ↑ On Baptism 8:6 online, Against Praxeas, 26:2 online

- ↑ Against Noetus, 1:14 online

- ↑ Seventh Council of Carthage online

- ↑ A Sectional Confession of Faith, 13:2 online

- ↑ Kittel, 3:108.

- 1 2 Stagg, Frank. New Testament Theology. Broadman Press, 1962. ISBN 978-0-8054-1613-8, pp. 38 ff.

- ↑ Grudem, Wayne A. 1994. Systematic theology an introduction to biblical doctrine. Leicester, England: Inter-Varsity Press. Page 226.

- ↑ "Athanasian Creed". Ccel.org. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Barth, Karl, and Geoffrey William Bromiley. 1975. The doctrine of the word of God prolegomena to church dogmatics, being volume I, 1. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. Pages 348–9.

- ↑ Thomas, and Anton Charles Pegis. 1997. Basic writings of Saint Thomas Aquinas. Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett Pub. Pages 307–9.

- ↑ For 'person', see Richard De Smet, A Short History of the Person, available in Brahman and Person: Essays by Richard De Smet, ed. Ivo Coelho (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2010).

- ↑ "NPNF2-09. Hilary of Poitiers, John of Damascus | Christian Classics Ethereal Library". Ccel.org. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity: The Greek and the Latin Traditions regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit (scanned image of the English translation on L'Osservatore Romano of 20 September 1995); also text with Greek letters transliterated and text omitting two sentences at the start of the paragraph that it presents as beginning with "The Western tradition expresses first ..."

- ↑ CCC §236.

- ↑ Phillip Cary, Priscilla Papers Vol. 20, No. 4, Autumn 2006

- ↑ "Basil the Great, De Spiritu Sancto, NPNF, Vol 8". Ccel.org. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Athanasius, 3.29 (p. 409)

- ↑ Basil "Letters", NPNF, Vol 8, 189.7 (p. 32)

- ↑ Sauvage, George. "Appropriation." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 20 October 2016

- ↑ Stefon, Matt (December 10, 2015). "Christianity - The Holy Trinity | Attempts to define the Trinity". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Augustine (2002). "9.1.1". In Matthews, Gareth B. On the Trinity. Books 8—15. Translated by Stephen McKenna. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-5217-9665-2. ISBN 978-0-521-7966-51.

- ↑ (in Latin) Veluti nunc cupimus videre utrum illa excellentissima caritas proprie Spiritus Sanctus sit. Quod si non est, aut Pater est caritas, aut Filius, aut ipsa Trinitas, quoniam resistere non possumus certissimae fidei, et validissimae auctoritati Scripturae dicentis: 'Deus caritas est'.

- ↑ Augustine (2002). 9.2.2.

- ↑ (in Latin) Tria ergo sunt: amans, et quod amatur, et amor.

- ↑ See occurrences on Google Books.

- ↑ Balthasar, Hans Urs von (2000) [1990]. "Preface to the Second Edition". Mysterium Paschale. The Mystery of Easter. Translated with an Introduction by Aidan Nichols, O.P. (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Ignatius Press. ISBN 1-68149348-9. ISBN 978-1-681-49348-0.

- ↑ Balthasar, Hans Urs von (1998). Theo-Drama. Theological Dramatic Theory, Vol. 5: The Last Act. Translated by Graham Harrison from the German Theodramatik. Das Endspiel, 1983. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. ISBN 1-68149579-1.

ISBN 978-1-681-49579-8.

it must be said that this "kenosis of obedience"...must be based on the eternal kenosis of the Divine Persons one to another.

- ↑ Carson, Donald Arthur (2010) [2000]. The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God (reprint, revised ed.). London: Inter-Varsity Press. p. 10. ISBN 1-84474427-2.

ISBN 978-1-844-74427-5.

Quoted in Mabry, Adam (2014). Life and Doctrine. How the Truth and Grace of the Christian Story Change Everything. Morrisville, North Carolina: Lulu.com. ISBN 1-31224685-5.

ISBN 978-1-312-24685-0.

If people believe in God at all today, the overwhelming majority hold that this God...is a loving being...this widely disseminated belief in the love of God is set with increasing frequency in some matrix other than biblical theology. The result is that when informed Christians talk about the love of God, they mean something very different from what is meant in the surrounding culture.

(p. 68). - ↑ Kitamori, Kazoh (2005). Theology of the Pain of God. Translated by Graham Harrison from the Japanese Kami no itami no shingaku, revised edition 1958, first edition 1946. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 1-59752256-2. ISBN 978-1-597-52256-4.

- ↑ Moltmann, Jürgen (2015). The Crucified God. Translated by R. A. Wilson and John Bowden from the German Der gekreuzigte Gott, 1971. London: SCM Press. ISBN 0-33405330-7. ISBN 978-0-334-05330-9.

- ↑ (in Latin) DS 401 (Pope John II, letter Olim quidem addressed to the senators of Constantinople, March 534).

- ↑ Balthasar, Hans Urs von (1992). Theo-drama. Theological Dramatic Theory. Vol. 3: Dramatis Personae: Persons in Christ. Translated by Graham Harrison from the German Theodramatik: Teil 2. Die Personen des Spiels : Die Personen in Christus, 1973. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. ISBN 1-68149577-5.

ISBN 978-1-681-49577-4.

Quote.

- 1 2 Olsen, Roger E., "Is there hierarchy in the Trinity?", Patheos, December 8, 2011.

- ↑ Warfield, Benjamin B., "Trinity", § 20, The Question of Subordination, The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia, Vol. 5, (James Orr, ed.), Howard-Severance Company, 1915, pp.3020-3021.

- ↑ Rubinstein, Richard. When Jesus Became God, The Struggle to Define Christianity During the Last Days of Rome. p. 64.

- ↑ Harvey, Susan Ashbrook; Hunter, David G. (4 September 2008). "The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Studies". OUP Oxford – via Google Books.

- ↑ "What Was Debated at the Council of Nicea?".

- ↑ Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church. Volume III. Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity, fifth edition revised, §27

- 1 2 Rusch, William G. (1980). "Introduction". In Rusch, William G. The Trinitarian Controversy. Minneapolis: Fortress Press(subscription required). p. 2.

- ↑ "Neither the word Trinity nor the explicit doctrine appears in the New Testament ... the New Testament established the basis for the doctrine of the Trinity"(Encyclopædia Britannica Online: article Trinity).

- ↑ "Trinity". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- 1 2 The Oxford Companion to the Bible (ed. Bruce Metzger and Michael Coogan) 1993, p. 782–3.

- ↑ McGrath, Alister E.Understanding the Trinity. Zondervan, 9789 ISBN 0-310-29681-1

- ↑ Harris, Stephen L. Understanding the Bible. Mayfield Publishing: 2000. pp. 427–428

- ↑ See, for instance, the note in 1 Jn 5:7–8.

- ↑ Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2d ed. Oxford University, 1968 p.101

- ↑ "The Presentation of Jesus in John's Gospel". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Brown, Raymond E. The Anchor Bible: The Gospel According to John (XIII–XXI), pp. 1026, 1032

- ↑ Hoskyns, Edwyn Clement (ed Davey F.N.) The Fourth Gospel Faber & Faber, 1947 p.142 commenting on "without him was not any thing made that was made."[John 1:3]

- ↑ St. Paul helps us understand truths about Jesus Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Simonetti, Manlio. "Matthew 14–28." New Testament Volume 1b, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture. Intervarsity Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8308-1469-5

- ↑ St. Augustine of Hippo,De Trinitate, Book I, Chapter 3.

- 1 2 3 4 St. Basil the Great,On the Holy Spirit Chapter 16.

- ↑ St. Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit Chapter 19.

- ↑ St. Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit Chapter 21.

- ↑ "Catholic Encyclopedia: article ''Pneumatomachi''". Newadvent.org. 1 June 1911. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ New Jerusalem Bible, Standard Edition published 1985, introductions and notes are a translation of those that appear in La Bible de Jerusalem—revised edition 1973, Bombay 2002; footnote to Joh 14:16.

- ↑ Zondervan NIV (New International Version) Study Bible, 2002, Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA; footnote to Joh 14:17.

- ↑ Trinity—see "3 The Holy Spirit As a Person".

- ↑ See Book of Wisdom#Messianic interpretation by Christians

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press, 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article Trinity, doctrine of the

- 1 2 "Catholic Encyclopedia: article ''The Blessed Trinity''". Newadvent.org. 1 October 1912. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia of Religion", Vol. 14, p.9360, on Trinity

- ↑ Gregory Nazianzen, Orations, 31.26

- ↑ For the two chapters as a single text, see Letellier, Robert. Day in Mamre, night in Sodom: Abraham and Lot in Genesis 18 and 19. Brill Publishers: 1995. ISBN 978-90-04-10250-7 pp.37ff. Web: 9 January 2010

- 1 2 3 "Francis Watson, Abraham's Visitors, The Journal of Scriptural Reasoning, Number 2.3, September 2002". Etext.lib.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Swedenborg, Emanuel. Heavenly Arcana, 1749–58. Rotch Edition. New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1907, in the Divine Revelation of the New Jerusalem (2012), n. 2149, 2156, 2218.

- ↑ Swedenborg, n. 2319–2320.

- ↑ Swedenborg, n. 10617.

- ↑ The Trinity in the Old Testament Archived 4 May 2003 at Archive.is

- ↑ Larry W. Hurtado, Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2005 ISBN 0-8028-3167-2 pp. 573–578

- ↑ "Baker's Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology: ''Angel of the Lord''". Studylight.org. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Aurelius, Marcus (1964). Meditations. London: Penguin Books. p. 25. ISBN 0-14044140-9. ISBN 978-0-140-44140-6.

- ↑ See below and G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I, 1971, Vol II, 1972, (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, figs I;5–16 & passim, ISBN 0-85331-270-2 and ISBN 0-85331-324-5

- ↑ Cartlidge, David R., and Elliott, J.K.. Art and the Christian Apocrypha, pp. 69–72 (illustrating examples), Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0-415-23392-5, ISBN 978-0-415-23392-7, Google books

- ↑ G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II, 1972, (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, figs I;5–16 & passim, ISBN 0-85331-270-2 and ISBN 0-85331-324-5, pp. 122–124 and figs 409–414

- ↑ G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II, 1972, (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, figs I;5–16 & passim, ISBN 0-85331-270-2 and ISBN 0-85331-324-5, pp. 219–224 and figs 768–804

- ↑ Potts, Albert M. The World's Eye. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 68–78.

- ↑ von Harnack, Adolf (1 March 1894). "History of Dogma". Retrieved 15 June 2007.

[In the 2nd century,] Jesus was either regarded as the man whom God hath chosen, in whom the Deity or the Spirit of God dwelt, and who, after being tested, was adopted by God and invested with dominion, (Adoptionist Christology); or Jesus was regarded as a heavenly spiritual being (the highest after God) who took flesh, and again returned to heaven after the completion of his work on earth (pneumatic Christology)

- ↑ Cross, F.L. (1958). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. London: OUP, p. 81.

- 1 2 Glassé, Cyril; Smith, Huston (2003). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Rowman Altamira. pp. 239–241. ISBN 0759101906.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Qur'an. Thomas, David. 2006. Volume V: Trinity.

- ↑ Quran 3:79–80 (Translated by Shakir)

- ↑ Quran 112:1–4 (Translated by Shakir)

- ↑ Quran 112:1–4 (Translated by Shakir)

- ↑ Quran 5:73 (Translated by Shakir)

- ↑ Quran 5:116 (Translated by Shakir)

- 1 2 3 David Thomas, Trinity, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ Mun'im Sirry (1 May 2014). Scriptural Polemics: The Qur'an and Other Religions. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ S. Griffith: Christians and Christianity.

- ↑ Edward Hulmes: Qur'an and the Bible, The; entry in the Oxford Companion to the Bible.

- ↑ Mun'im Sirry (1 May 2014). Scriptural Polemics: The Qur'an and Other Religions. Oxford University Press. p. 47.

- ↑ The concept of Trinity is incompatible with Judaism:

- Response - Reference Center - FAQ - Proof Texts - Trinity (Jews for Judaism)

- The Trinity in the Shema? by Rabbi Singer (outreachjudaism.org)

- The Doctrine of the Trinity (religionfacts.com)

Other references

- Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy Online, Trinity

Further reading

- Emery, Gilles, O.P.; Levering, Matthew, eds. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of the Trinity. ISBN 978-0199557813.

- Holmes, Stephen R. (2012). The Quest for the Trinity: The Doctrine of God in Scripture, History and Modernity. ISBN 9780830839865.

- Dolezal, James. "Trinity, Simplicity and the Status of God's Personal Relations", International Journal of Systematic Theology 16 (1) (2014): 79–98.

- Fiddes, Paul, Participating in God : a pastoral doctrine of the Trinity (London: Darton, Longman, & Todd, 2000).

- Johnson, Thomas K., "What Difference Does the Trinity Make?" (Bonn: Culture and Science Publ., 2009).

- La Due, William J., The Trinity guide to the Trinity (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003 ISBN 1-56338-395-0, ISBN 978-1-56338-395-3).

- Letham, Robert (2004). The Holy Trinity : In Scripture, History, Theology, and Worship. ISBN 9780875520001.

- O'Collins, Gerald (1999). The Tripersonal God: Understanding and Interpreting the Trinity. ISBN 9780809138876.

- Olson, Roger E.; Hall, Christopher A. (2002). The Trinity. ISBN 9780802848277.

- Phan, Peter C., ed. (2011). The Cambridge Companion to the Trinity. ISBN 978-0-521-87739-8.

- So, Damon W. K., Jesus' Revelation of His Father: A Narrative-Conceptual Study of the Trinity with Special Reference to Karl Barth. (Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2006). ISBN 1-84227-323-X.

- Hillar, Marian, From Logos to Trinity. The Evolution of Religious Beliefs from Pythagoras to Tertullian. (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- Tuggy, Dale (Summer 2014), "Trinity (History of Trinitarian Doctrines)", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Feazell, J. and Morrison, M. (2013). You're Included — Complete List of Trinitarian Conversations, 108 Interviews With 25 Theologians: Ray S. Anderson, Douglas A. Campbell, Elmer Colyer, Gerrit Scott Dawson, Cathy Deddo, Gary W. Deddo, Gordon Fee, Trevor Hart, George Hunsinger, Christian Kettler, C. Baxter Kruger, John E. McKenna, Jeff McSwain, Steve McVey, Paul Louis Metzger, Paul Molnar, Roger Newell, Cherith Fee Nordling, Robin Parry, Andrew Purves, Andrew Root, Alan Torrance, David Torrance, Robert T. Walker, William Paul Young. 4th ed. ebook Grace Communion International, pp. 1–1279.

- Webb, Eugene, In Search of The Triune God: The Christian Paths of East and West (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2014)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Holy Trinity. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Trinity |

- Trinity Entry at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- A Formulation and Defense of the Doctrine of the Trinity A brief historical survey of patristic Trinitarian thought

- Doctrine of the Trinity

- Trinity Article at Theopedia

- Eastern Orthodox Trinitarian Theology

- Doctrine of the Trinity Reading Room: Extensive collection of on-line sources on the Trinity (Tyndale Seminary)