Abu Hanifa

| Abū Ḥanīfah أبو حنيفة نعمان بن ثابت بن زوطا بن مرزبان ابوحنیفه | |

|---|---|

Nuʿmān ibn Thābit ibn Zūṭā ibn Marzubān with Islamic calligraphy | |

| Title | The Great Imam |

| Born |

699 (80 Hijri) Kufa, Umayyad Caliphate |

| Died |

767 (150 Hijri) Baghdad, Abbasid Caliphate |

| Ethnicity | Persian[1][2][3][4] |

| Era | Islamic golden age |

| Region | Kufa[1] |

| Religion | Islam |

| Main interest(s) | Jurisprudence |

| Notable idea(s) | Istihsan |

| Notable work(s) | Al-Fiqh al-Akbar |

|

Influenced by

| |

|

Influenced

| |

| |

|---|

.jpg) |

|

Lists |

|

|

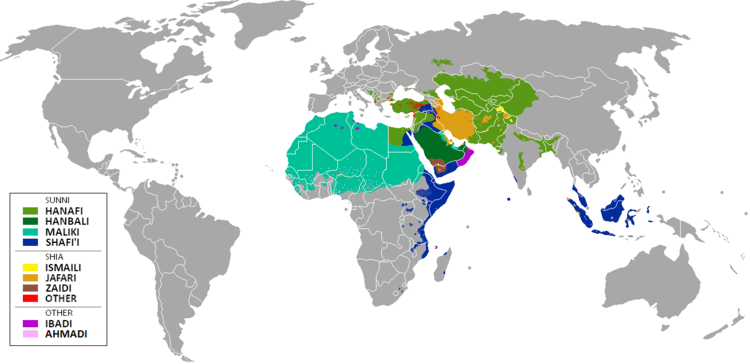

Abū Ḥanīfa al-Nuʿmān b. Thābit b. Zūṭā b. Marzubān (Arabic: أبو حنيفة نعمان بن ثابت بن زوطا بن مرزبان; c. 699 – 767 CE), known as Abū Ḥanīfa for short, or reverently as Imam Abū Ḥanīfa by Sunni Muslims,[5] was an 8th-century Sunni Muslim theologian and jurist of Persian origin,[6] who became the eponymous founder of the Hanafi school of orthodox Sunni jurisprudence, which has remained the most widely practiced law school in the Sunni tradition.[6] He is often alluded to by the reverential epithets al-Imām al-aʿẓam ("The Great Imam") and Sirāj al-aʾimma ("The Lamp of the Imams") in Sunni Islam.[6][3]

Born to a Muslim family in Kufa,[6] Abu Hanifa is known to have travelled to the Hejaz region of Arabia in his youth, where he studied under the most renowned teachers in Mecca and Medina at the time.[6] As his career as a theologian and jurist progressed, Abu Hanifa became known for favoring the use of reason in his legal rulings (faqīh dhū raʾy) and even in his theology.[6] Abu Hanifa's theological school is what would later develop into the Maturidi school of orthodox Sunni theology.[6]

He is also considered a renowned Islamic scholar and personality by Zaydi Shia Muslims.[7]

Life

Childhood

Abū Ḥanīfah was born in the city of Kufa in Iraq,[8][9] during the reign of the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan. His father, Thabit bin Zuta, a trader from Kabul (today in Afghanistan), was 40 years old at the time of Abū Ḥanīfah's birth.

His ancestry is generally accepted as being of Persian origin as suggested by the etymology of the names of his grandfather (Zuta) and great-grandfather (Mah). The historian Al-Khatib al-Baghdadi records a statement from Imām Abū Ḥanīfah's grandson, Ismail bin Hammad, who gave Abū Ḥanīfah's lineage as Thabit bin Numan bin Marzban and claiming to be of Persian origin.[3][4] The discrepancy in the names, as given by Ismail of Abū Ḥanīfah's grandfather and great-grandfather, are thought to be due to Zuta's adoption of the Arabic name (Numan) upon his acceptance of Islam and that Mah and Marzban were titles or official designations in Persia, with the latter, meaning a margrave, referring to the noble ancestry of Abū Ḥanīfah's family as the Sasanian Marzbans (equivalent of margraves). The widely accepted opinion, however, is that most probably he was of Persian ancestry .[3][4]

Adulthood and death

In 763, al-Mansur, the Abbasid monarch offered Abu Hanifa the post of Chief Judge of the State, but he declined the offer, choosing to remain independent. His student Abu Yusuf was later appointed Qadi Al-Qudat (Chief Judge of the State) by the Caliph Harun al-Rashid.[10]

In his reply to al-Mansur, Abū Ḥanīfah said that he was not fit for the post. Al-Mansur, who had his own ideas and reasons for offering the post, lost his temper and accused Abū Ḥanīfah of lying.

"If I am lying," Abū Ḥanīfah said, "then my statement is doubly correct. How can you appoint a liar to the exalted post of a Chief Qadi (Judge)?"

Incensed by this reply, the ruler had Abū Ḥanīfah arrested, locked in prison and tortured. He was never fed nor cared for.[11] Even there, the jurist continued to teach those who were permitted to come to him.

On the 15 Rajab 150[12] (August 15, 767[13]), Abū Ḥanīfah died in prison. The cause of his death is not clear, as some say that Abū Ḥanīfah issued a legal opinion for bearing arms against Al-Mansur, and the latter had him poisoned.[14] The fellow prisoner and Jewish Karaite founder, Anan Ben David, is said to have received life-saving counsel from the subject.[15] It was said that so many people attended his funeral that the funeral service was repeated six times for more than 50,000 people who had amassed before he was actually buried. On the authority of the historian al-Khatib, it can be said that for full twenty days people went on performing funeral prayer for him. Later, after many years, the Abū Ḥanīfah Mosque was built in the Adhamiyah neighbourhood of Baghdad.

The tomb of Abū Ḥanīfah and the tomb of Abdul Qadir Gilani were destroyed by Shah Ismail of Safavi empire in 1508.[16] In 1533, Ottomans conquered Baghdad and rebuilt the tomb of Abū Ḥanīfah and other Sunni sites.[17]

Sources and methodology

The sources from which Abu Hanifa derived Islamic law, in order of importance and preference, are: the Qur'an, the authentic narrations of the Muslim prophet Muhammad (known as hadith), consensus of the Muslim community (ijma), analogical reasoning (qiyas), juristic discretion (istihsan) and the customs of the local population enacting said law (urf). The development of analogical reason and the scope and boundaries by which it may be used is recognized by the majority of Muslim jurists, but its establishment as a legal tool is the result of the Hanafi school. While it was likely used by some of his teachers, Abu Hanifa is regarded by modern scholarship as the first to formally adopt and institute analogical reason as a part of Islamic law.[18]

As the fourth Caliph, Ali had transferred the Islamic capital to Kufa, and many of the first generation of Muslims had settled there, the Hanafi school of law based many of its rulings on the prophetic tradition as transmitted by those first generation Muslims residing in Iraq. Thus, the Hanafi school came to be known as the Kufan or Iraqi school in earlier times. Ali and Abdullah, son of Masud formed much of the base of the school, as well as other personalities from the direct relatives (or Ahli-ll-Bayṫ) of Moḥammad from whom Abu Hanifa had studied such as Muhammad al-Baqir (thus apparently creating a link between Sunnis and Shias). Many jurists and historians had reportedly lived in Kufa, including one of Abu Hanifa's main teachers, Hammad ibn Abi Sulayman.

Generational status

Abū Ḥanīfah is regarded by some as one of the Tabi‘un, the generation after the Sahaba, who were the companions of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad. This is based on reports that he met at least four Sahaba including Anas ibn Malik,[8] with some even reporting that he transmitted Hadith from him and other companions of Muhammad.[19][20] Others take the view that Abū Ḥanīfah only saw around half a dozen companions, possibly at a young age, and did not directly narrate hadith from them.[19]

Abū Ḥanīfah was born 67 years after the death of Muhammad, but during the time of the first generation of Muslims, some of whom lived on until Abū Ḥanīfah's youth. Anas bin Malik, Muhammad's personal attendant, died in 93 AH and another companion, Abul Tufail Amir bin Wathilah, died in 100 AH, when Abū Ḥanīfah was 20 years old. The author of al-Khairat al-Hisan collected information from books of biographies and cited the names of Muslims of the first generation from whom it is reported that the Abu Hanifa had transmitted hadith. He counted them as sixteen, including Anas ibn Malik, Jabir ibn Abd-Allah and Sahl ibn Sa'd.[21]

Reception

Abu Hanifa ranks as one of the greatest jurists of Islamic civilization and one of the major legal philosophers of the entire human community.[22] He attained a very high status in the various fields of sacred knowledge and significantly influenced the development of Muslim theology.[23] During his lifetime he was acknowledged by the people as a jurist of the highest calibre.[24]

Outside of his scholarly achievements Abu Hanifa is popularly known amongst Sunni Muslims as a man of the highest personal qualities: a performer of good works, remarkable for his self-denial, humble spirit, devotion and pious awe of God.[25]

His tomb, surmounted by a dome erected by admirers in 1066 is still a shrine for pilgrims.[22] It was given a restoration in 1535 by Suleiman the Magnificent upon the Ottoman conquest of Baghdad.[17]

The honorific title al-Imam al-A'zam ("the greatest leader") was granted to him[26] both in communities where his legal theory is followed and elsewhere. According to John Esposito, 41% of all Muslims follow the Hanafi school.[27]

Abu Hanifa also had critics. The Zahiri scholar Ibn Hazm quotes Sufyan ibn `Uyaynah: "[T]he affairs of men were in harmony until they were changed by Abù Hanìfa in Kùfa, al-Batti in Basra and Màlik in Medina".[28] Early Muslim jurist Hammad ibn Salamah once related a story about a highway robber who posed as an old man to hide his identity; he then remarked that were the robber still alive he would be a follower of Abu Hanifa.[29]

Early Islam scholars

Early Islamic scholars | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Works

- Al-Fiqh al-Akbar

- Al-Fiqh al-Absat

- Kitaab-ul-Aathaar narrated by Imam Muhammad al-Shaybani & Imam Abu Yusuf – compiled from a total of 70,000 hadith

- Aalim wa'l-muta‘allim

- At Tareeq Al Aslam Musnad Imam ul A’zam Abu Hanifah

Confusion regarding Al-Fiqh Al-Akbar

The attribution of Al-Fiqh Al-Akbar has been disputed by A.J. Wensick,[30] as well as Zubair Ali Zai.[31]

Other scholars have upheld that Abu Hanifa was the author such as Muhammad Zahid Al-Kawthari, al-Bazdawi, and Abd al-Aziz al-Bukhari.[32]

Scholars such as Mufti Abdur-Rahman have pointed out that the book being brought into question by Wensick is actually another work by Abu Hanifa called: "Al-Fiqh Al-Absat".[32]

Citations

- 1 2 3 A.C. Brown, Jonathan (2014). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oneworld Publications. pp. 24–5. ISBN 978-1780744209.

- ↑ Mohsen Zakeri (1995), Sasanid soldiers in early Muslim society: the origins of 'Ayyārān and Futuwwa, p.293

- 1 2 3 4 S. H. Nasr (1975), "The religious sciences", in R.N. Frye, The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4, Cambridge University Press. pg 474: "Abū Ḥanīfah, who is often called the "grand imam"(al-Imam al-'Azam) was Persian

- 1 2 3 Cyril Glasse, "The New Encyclopedia of Islam", Published by Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. pg 23: "Abu Hanifah, a Persian, was one of the great jurists of Islam and one of the historic Sunni Mujtahids"

- ↑ ABŪ ḤANĪFA, Encyclopædia Iranica

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pakatchi, Ahmad and Umar, Suheyl, “Abū Ḥanīfa”, in: Encyclopaedia Islamica, Editors-in-Chief: Wilferd Madelung and, Farhad Daftary.

- ↑ Abu Bakr al-Jassas al-Razi. Ahkam al-Quran. Dar Al-Fikr Al-Beirutiyya. pp. volume 1 page 100.

- 1 2 Meri, Josef W. (October 31, 2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 9781135456030.

- ↑ Hisham M. Ramadan, Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary, (AltaMira Press: 2006), p.26

- ↑ "Oxford Islamic Studies Online". Abu Yusuf. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Ya'qubi, vol. III, p.86; Muruj al-dhahab, vol. III, pp. 268–270.

- ↑ Ammar, Abu (2001). "Criticism levelled against Imam Abu Hanifah". Understanding the Ahle al-Sunnah: Traditional Scholarship & Modern Misunderstandings. Islamic Information Centre. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- ↑ "Islamic Hijri Calendar For Rajab - 150 Hijri". habibur.com. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- ↑ Najeebabadi, Akbar S. (2001). The History of Islam. vol, 2. Darussalam Press. pp. 287. ISBN 9960-892-88-3.

- ↑ Nemoy, Leon. (1952). Karaite Anthology: Excerpts from the Early Literature. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. pp. 4-5. ISBN 0-300-00792-2.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire

- 1 2 Burak, Guy (2015). The Second Formation of Islamic Law: The Ḥanafī School in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-107-09027-9.

- ↑ See:

*Reuben Levy, Introduction to the Sociology of Islam, pg. 236–237. London: Williams and Norgate, 1931–1933.

*Chiragh Ali, The Proposed Political, Legal and Social Reforms. Taken from Modernist Islam 1840–1940: A Sourcebook, pg. 280. Edited by Charles Kurzman. New York City: Oxford University Press, 2002.

*Mansoor Moaddel, Islamic Modernism, Nationalism, and Fundamentalism: Episode and Discourse, pg. 32. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

*Keith Hodkinson, Muslim Family Law: A Sourcebook, pg. 39. Beckenham: Croom Helm Ltd., Provident House, 1984.

*Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary, edited by Hisham Ramadan, pg. 18. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

*Christopher Roederrer and Darrel Moellendorf, Jurisprudence, pg. 471. Lansdowne: Juta and Company Ltd., 2007.

*Nicolas Aghnides, Islamic Theories of Finance, pg. 69. New Jersey: Gorgias Press LLC, 2005.

*Kojiro Nakamura, "Ibn Mada's Criticism of Arab Grammarians." Orient, v. 10, pgs. 89–113. 1974 - 1 2 Imām-ul-A’zam Abū Ḥanīfah, The Theologian

- ↑ http://www.islamicinformationcentre.co.uk/alsunna7.htm last accessed June 8, 2011

- ↑ "Imam-ul-A'zam Abū Ḥanīfah, The Theologian". Masud.co.uk. Archived from the original on February 12, 2010. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- 1 2 Magill, Frank Northen (January 1, 1998). Dictionary of World Biography: The Middle Ages. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 9781579580414.

- ↑ Magill, Frank Northen (January 1, 1998). Dictionary of World Biography: The Middle Ages. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 9781579580414.

- ↑ Hallaq, Wael B. (January 1, 2005). The Origins and Evolution of Islamic Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 9780521005807.

- ↑ Waines, David (November 6, 2003). An Introduction to Islam. Cambridge University Press. p. 66. ISBN 9780521539067.

- ↑ Houtsma, M. Th (January 1, 1993). E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936. BRILL. p. 840. ISBN 9004097902.

- ↑ Esposito, John (2017). "The Muslim 500: The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims" (PDF). The Muslim 500. p. 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ↑ Camilla Adang, "This Day I have Perfected Your Religion For You: A Zahiri Conception of Religious Authority," p.33. Taken from Speaking for Islam: Religious Authorities in Muslim Societies. Ed. Gudrun Krämer and Sabine Schmidtke. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2006

- ↑ Ignác Goldziher, The Zahiris, pg. 15. Volume 3 of Brill Classics in Islam. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2008. ISBN 9789004162419

- ↑ Wensick, A.J. (1932). The Muslim Creed. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 125.

- ↑ Zubair Ali ZaiIs Fiqh ul-Akbar Imaam Abu Haneefah's book. Taken from The Story of the Fabricated book and the Rabbaanee Scholars, pg. 19–20. Trns. Abu Hibbaan and Abu Khuzaimah Ansaari.

- 1 2 Ibn Yusuf Mangera, Mufti Abdur-Rahman (November 2007). Imam Abu Hanifa's Al-Fiqh Al-Akbar Explained (First ed.). California, USA: White Thread Press. pp. 24–35. ISBN 978-1-933764-03-0.

References

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Abu Hanifa |

- al-Quduri, Ahmad ibn Muhammad (2010). Mukhtasar al-Quduri. Translated by Tahir Mahmood al-Kiani (First ed.). Ta-Ha Publishers Ltd. ISBN 1842001183.

- Nu'mani, Shibli (1998). Imām Abū Ḥanīfah — Life and Works. Translated by M. Hadi Hussain. Islamic Book Service, New Delhi. ISBN 81-85738-59-9.

- Abdur-Rahman ibn Yusuf, Imam Abu Hanifa's Al-Fiqh Al-Akbar Explained

External links

- The Life of Imam Abu Hanifa Biography at Lost Islamic History

- Imam Abu Hanifa by Jamil Ahmad

- Al-Wasiyyah of Imam Abu Hanifah Translated into English by Shaykh Imam Tahir Mahmood al-Kiani

- Book on Imam e Azam Abu Hanifa (Urdu)

- Abu Hanifa on Muslim heritage

- Imām Abū Ḥanīfah By Shiekh G. F. Haddad

- Some teachers and students of Imam Abu Hanifa