Morteza Motahhari

| Morteza Motahari | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Head of Council of the Islamic Revolution | |

|

In office 12 January 1979 – 1 May 1979 | |

| Appointed by | Ruhollah Khomeini |

| Succeeded by | Mahmoud Taleghani |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Morteza Motahhari 31 January 1919 Fariman, Iran |

| Died |

1 May 1979 (aged 60) Tehran, Iran |

| Resting place | Fatima Masumeh Shrine, Qom |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Political party |

|

| Signature |

|

| Theological work | |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Twelver Shīʿā |

| School | Jaʿfari |

| Main interests | Islamic philosophy |

| Years active | 1944–1979 |

| Alma mater |

Qom Seminary University of Tehran |

| Taught at | University of Tehran |

|

Influenced

| |

|

Influenced by

| |

Morteza Motahari (Persian: مرتضی مطهری; January 31, 1919 – May 1, 1979) was an Iranian cleric, philosopher, lecturer, and politician.

Motahari is considered to have an important influence on the ideologies of the Islamic Republic, among others.[3] He was a co-founder of Hosseiniye Ershad and the Combatant Clergy Association (Jāme'e-ye Rowhāniyat-e Mobārez). He was a disciple of Ayatollah Khomeini during the Shah's reign and formed the Council of the Islamic Revolution at Khomeini's request. He was chairman of the council at the time of his assassination.[4]

Biography

Early life

Motahari was born in Fariman on January 31, 1919. He attended the Hawza of Qom from 1944 to 1952 and then left for Tehran.[5] His grandfather was an eminent religious scholar in Sistan province and since he traveled with his family to Khorasan Province, there is little information about his origin as Sistanian.[6] His father Shaykh Mohammad Hosseini was also an eminent figure in his village, Fariman, who was respected by the people. He was considered as one of the pupils of Akhund Khorasani and besides he was admired by Ayatollah Mara'shi Najafi.[7]

Education

It is said that he was very intelligent as a child. At the age of 5, he went to school without informing his parents. Sometimes he was found sleeping near the school. By the age of twelve he learned the preliminary Islamic sciences from his father. He also went to the seminary of Mashhad and studied for two years there in the school of Abd ul-Khan along with his brother. But his studies remained unfinished in Mashhad seminary because of problems faced by his family which obliged him to return to Fariman to help them.

According to his own account, in this period he could study a great number of historical books. It was in this period that he was confronted with questions on worldview such as the problem of God. He considered Agha Mirza Mahdi Shahid Razavi as an eminent master in rational sciences. He decided to go to Qom in 1315 Solar Hijri calendar.[8]

He finally took up residence in the school of Feyzieh in Qum. He studied books Kifayah and Makaseb in Shia jurisprudence under instruction of Ayatollah Sayyed Mohaqeq Yazdi popularly known as Damad. He also participated in the lectures of Hojjat Kooh Kamarehei ant sough knowledge from Sayyed Sadr Al Din Sadr, Mohammad Taqi Khansari, Golpaygani, Aaahmad Khansari and Najafi Marashi.[8]

When Ayatollah Boroujerdi emigrated to Qom, Motahari could take part in his courses on Principles of Jurisprudence. Ayatollah Montazeri was his classmate in this period.[8]

Later, Motahari emigrates to Isfahan because of hot climate of Qom. There he becomes familiar with Haj Ali Agha Shirazi who was the teacher of Nahj Al Balaghah in 1320 Solar Hijri calendar who Motahari always describes with honor.[8] Later, he joined the University of Tehran, where he taught philosophy for 22 years. Between 1965 and 1973 he also gave regular lectures at the Hosseiniye Ershad in Northern Tehran.

Motahari wrote several books on Islam, Iran, and historical topics. His emphasis was on teaching rather than writing. However, after his death, some of his students worked on writing down his lectures and publishing them as books. As of the mid-2008, the "Sadra Publication" published more than sixty volumes by Motahari. Nearly 30 books were written about Motahari or quoted from his speeches.

Morteza Motahari opposed what he called groups who "depend on other schools, especially materialistic schools" but who present these "foreign ideas with Islamic emblems". In a June 1977 article he wrote to warn "all great Islamic authorities" of the danger of "these external influential ideas under the pretext and banner of Islam." It is thought he was referring to the People's Mujahideen of Iran and the Furqan Group.[9]

Motahari was the father in law of Iran's former secretary of National Security Council Ali Larijani.[10] It was by Motahari's advice that Larijani switched from computer science to Western Philosophy for graduate studies.

A major street in Tehran formerly known as Takhte Tavoos (Peacock Throne) was renamed after him. Morteza Motahari Street connects Sohrevardi Street and Vali Asr Street, two major streets in Tehran.

Activities during Islamic revolution

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Iranian Revolution |

|

|

Revolutionary leaders

|

|

Official institutions |

|

See also |

During the struggle with shah’s regime, Morteza Motahari contributed in creating new Islamic discourses. Besides, he was among those who had discussed the conditions of Marja' after the death of Ayatollah Broujerdi. He wrote the book Mutual services of Iran and Islam in such a condition. Also his works had important impact on expanding the movement of religious reform in early days of revolution. His works primarily consisted of traditional Islamic and Shia thoughts.[11] He wrote an essay about revitalization of religious thought in the occasion. Writing the "need for Candidness in religious leadership", he aimed to show the youth the attractiveness of Islam.[12]

During the revolution, while Shapour Bakhtiyar prevented Khomeini's return to Iran in 1978, Ayatollah Motahari was the leader who managed the protester clergies in Tehran University's mosque. Motahari was an important figure, and helped Ayatollah Khomeini to organize revolutionary department.

Opinions

Morteza Motahari expressed his opinions in different majors and disciplines such as philosophy, religion, economic, politics and etc. Motahari and Shariati were counted as two prominent figures during Islamic revolution of Iran. He emphasized on Islamic democracy for suitable political structure.[13]

Motahari also recognized fitra as the truth of human. According to him, fitra is a permanent and unchangeable quality in human nature. In fact, he believed that fitra played the role of a mediator in God-human beings relation. Also, he believed that Imam was a perfect man who shows the high rank of human spirituality. Imam also is characterized as a religious leader. His lengthy footnote on the “book of principles of philosophy and method of realism” by Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i was against the historical Marxism.[14] Also he believed that Wali-e faqih only had the right of supervisory not governing.[15] He also maintained that the ruling was one of the political aspect of Imam in society.[16] He maintained that there was no conflict between science and religion since he believed that Science qua science had no conflict and challenge with metaphysics. He believed that the quasi-conflict between science and religion was in terms of their language not themselves.[17]

Development

Motahari also expressed views on development and relevant ideology. According to him, freedom, culture and mental-cultural revolution are principles of development. He also refers to some elements for characterizing a developed society.these factors are independence, knowledge and transcendence. Also, according to Motahari, development originates from cultural self-reliance, purification of cultural sources and logical and cautious communication with west. Motahari believed in the development of human resources but he also thought that economy was not an aim but only is a condition for development.[13]

Equality

As outlined by Ayatollah Morteza Motahari in 1975, the phrase ‘equal rights’ means something different from what is commonly understood by western world. He clarified that men and women were innately different and therefore enjoyed different rights, duties and punishments.[18]

Fiqh

Motahari believed that the eternality of Islam is provided by Fiqh. He thought that fiqh along with the character of ijtihad could be an important thing for confronting with the problem of different times and places. Using ijtihad, there is no need to a new prophet.[15]

Anthropology

Motahari also believed that there were great challenges between scientists for knowing the human as a phenomenon and at the same time we can rarely find two philosophers who have common ideas in their approach toward studying humanity.[19]

Freedom

Motahari defined freedom as nonexistence of obstacles. According to him, obstacles were of two characters. The first one was that obstacle could limit human and besides counted as a something get human not to do something. In simple word, obstacle could has the dignity of limiting and declining humans.the second one is to thing which decline the perception and introspection of subject in terms of knowledge. According to Motahhari, aside from the realization of putting away obstacles we need to give the spirit of freedom. He analyze the concept of freedom as both right and obligation.He believes that the freedom has necessity for human. Human must be free to choose voluntarily his path. He believes that, contrary to liberalists, inborn right has an ultimate for transcending of human beings.[20]

Philosophy of law

Like other men of thought, Motahari thinks that we have to define the concepts first of all. Therefore, he defines right as a dominance or score on something. According to right the human is merit to possess something and other human ought to respect him. Some of rights are such as the right of parents on their children or the rights of husband and wife in relation to each other. Motahari divided the right into two groups. First group is existential rights Or Takwini and the second is religious rights or tashriei. former is a real relation between person and object and the latter determined according to former. He knew the right as a potential score for persons. In fact the right concerned with the priority of somebody on something. He concerned with the question in that is the right and possession predicated on human as such or predicated on human in terms of being in society? He believes that undoubtedly the right existed prior to society.Contrary to John Austin (legal philosopher), Motahari believes that there is a mutual relation between right and responsibility (Haq va Taklif). Motahari believes that the natural law theory is a rational one that is of importance for human kind. According to him, the foundation of natural theory of law is to world has a goal and aim finally. On the basis of principle of having goal, the God creates the world for the sake of human kind and they have potential right to change the world therefore human kind have right prior to introducing in society.[21]

Philosophy of religion

Motahari refers to the concept of Maktab or school when he intends to define the word of religion. According to him maktab is a thoughtful disciplined system including ideology and View in terms of ethics, politics, economy and civil law and etc. Finally, he defines religion as a collection of knowledge bestowed to human for the sake of guiding him and also religion is a collection of beliefs, moralities and individual and collective judgments. Therefore, he knows religion and its teaching as beliefs, moralities and judgments. Also Motahari believes that the domain of religion at all is not limited to life but concerned with after afterlife. He believes that Islam as a religion is consistent with life of human and there is no room for denying it.[22]

Western philosophy

Dariush Shayegan believes that Motahari confused the hegelian thought and Stace's quotations in confronting with Hegel. According to Shaygan since each of Motahari and hegel belong to different paradigms, there is no common world between them.[23]

Epistemology

He considered Marxism as a great threat for youths and revolution of Iran therefore he tried to criticize Marxism along with pioneer figures like shariati. Also his commentary on the book of Mulla Sadra influenced many scholars. Besides, he also emphasized on the social, cultural and historical contingencies of religious knowledge. Motahari argued that if someone compares fatwas belong to different jurists and at the same time considers their lives and states of knowledge then it is clear that the presuppositions of jurists and its knowledge affected their knowledge. According to him, because of this reason, we observe that the fatwa belong to Arab has an Arab flavor and the fatwa belong to non-Arab has an Ajam flavor. Also He tried to compare Quran with nature. He also believed that the contemporary interpretations of Quran were considerable than Ancient rendition of Islam because the future generation has a better understanding of Quran and Also a deeper appreciation of it. But At the same Time he doesn’t believe in epistemological pluralism.[24]

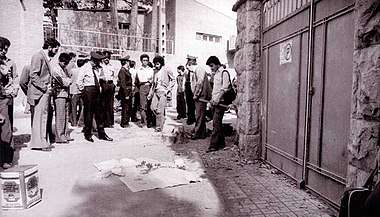

Assassination

Because of his activities, he was favored by revolutionary people and was hated by anti-revolutionaries group, such as the Islamist Furqan Group.[25] On 1 May 1979 Morteza Motahari was assassinated in Tehran by gunshot after leaving a late meeting at the house of Yadollah Sahabi.[26] The Furqan Group claimed responsibility for the assassination.[26] The alleged assassin was the group's founder, Akbar Goudarzi.[27]

Awards

- UNESCO Award, 1965.[28]

Publications

He "authored over fifty books, which dealt with theology and philosophy as well as practical issues such as sexual ethics, usury, and insurance",[29] some of which include:

- Tawhid (Monotheism)

- Adl -e- Elahi (Divine Justice)

- Nubuwwah (Prophet-hood)

- Ma'ad (The Return, a book on Islamic eschatology)

- Hamase -e- Husaini (Husaynian Epic)

- Seiry dar nahj al-balagha (A Journey through Nahj al-Balagha )

- Seiry dar sirey'e a'emeye at-har (A Journey through the Conduct of the Purified Imams)

- Seiry dar sirey'e nabavi (A Journey through the Prophetic Conduct)

- Insan -e- Kamel (The Complete Human)

- Payambar -e- Ommi (The Uneducated Prophet)

- Osool -e Falsafa va ravesh -e- Realism (The Principles of Philosophy and the Method of Realism)

- Sharh -e- Manzume (An exegesis on Mulla Hadi Sabzavari's versified summary of Mulla Sadra's Transcendent theosophy)

- Imamat va rahbary (Imamate and Leadership)

- Dah Goftar (A collection of 10 essays by Motahari)

- Bist Goftar (A collection of 20 essays by Motahari)

- Panzdah Goftar (A collection of 15 essays by Motahari)

- Azadi -e- Ma'navi (Spiritual Freedom)

- Ashneya'ei ba Quran (An Introduction to the Qur'an)

- Ayande -e- Enghlab -e- Islami (The Future of the Islamic Revolution)

- Dars -e- Qur'an (Lesson of Qur'an)

- Ehyaye Tafakor -e- Islami (Revival of Islamic Thinking)

- Akhlagh -e- Jensi (Sexual Ethics)

- Islam va niazha -ye- jahan (Islam and the Demands of the Modern World)

- Emdadhaye gheibi dar zendegi -e- bashar (Hidden Aids in Human Life)

- Ensan va sarnevesht (Man and Destiny)

- Panj maghale (Five Essays)

- Ta'lim va tarbiyat dar Islam (Education in Islam)

- Jazebe va dafe'eye Ali (Ali's Attraction and Repulsion)

- Jehad (The Holy War of Islam and Its Legitimacy in the Quran)

- Hajj (Pilgrimage)

- Hekmat-ha va andarz-ha (Wisdoms and Warnings)

- Khatemiyat (The Doctrine of the Seal of Prophethood by Muhammad)

- Khatm -e- Nobowat (The Seal of Prophethood)

- Khadamāt-e moteqābel-e Eslām va Īrān (Islam and Iran: A Historical Study of Mutual Services). A 750-pages book where he shows how Iran and Islam benefited each other. He also said that we can't reject nationalism as a whole: "Nationalism should not be condemned categorically, and when it conveys positive qualities, it leads to solidarity, good relations, and common welfare among those we live with. It is neither irrational nor is it contrary to Islam."[30]

- Dastan -e- Rastan (Anecdotes of Pious Men)

- Darshaye Asfar

- Shesh maghale (Six Essays)

- Erfan -e- Hafez

- Elale gerayesh be madigary

- Fetrat

- Falsafe -ye- Akhlagh (Ethics)

- Falsafe -ye- Tarikh (Philosophy of History)

- Ghiam va enghelab -e- Mahdi

- Koliyat -e- olume Islami

- Goft o gooye chahar janebe

- Masaleye Hejab

- Masaleye Reba

- Masaleye Shenakht

- Maghalate falsafi (A selection of Philosophical articles written by Motahari)

- Moghadameyi bar jahanbiniye Islami (Consists of 6 different books written about this subject)

- Nabard -e- hagh va batel

- Nezam -e- hoghoghe zan dar Islam

- Nazari bar nezame eghtesadiye Islam

- Naghdi bar Marxism (A critic on Marxism)

- Nehzat-haye Islami dar 100 sale akhir

- Sexual Ethics in Islam and in the Western World (English)

- Vela'ha va velayat-ha

- Azadegi

- Ayineye Jam (Interpretation of poetry of Hafez)

See also

References and notes

- ↑ Rahnema, Ali (February 20, 2013) [December 15, 2008]. "JAMʿIYAT-E MOʾTALEFA-YE ESLĀMI i. Hayʾathā-ye Moʾtalefa-ye Eslāmi 1963-79". Encyclopædia Iranica. Fasc. 5. XIV. New York City: Bibliotheca Persica Press. pp. 483–500. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ↑ R. Michael Feener (2004), Islam in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives, ABC-CLIO, p. 89, ISBN 9781576075166

- ↑ Manouchehr Ganji (2002). Defying the Iranian Revolution: From a Minister to the Shah to a Leader of Resistance. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-275-97187-8. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ↑ Debating Muslims Michael M. J. Fischer, Mehdi Abedi

- ↑ Kasra, Nilofar. "Ayatollah Morteza Motahari". IICHS. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ↑ اولین همایش مطهری سیستانی در زابلhttp://www.neyzarnews.ir

- ↑ Abdollah Nasri, Life's outcome, A survry of Murteza Motahari's ideas & 1386 solar, pp. 5–6

- 1 2 3 4 Nasri (1386). Lif's outcome:A survey of Morteza Motahari's Ideas. daftere Nashre Farhang. p. 5–10.

- ↑ Davari, Mahmood T. (1 October 2004). "The Political Thought of Ayatollah Murtaza Mutahhari: An Iranian Theoretician of the Islamic State". Taylor & Francis. Retrieved 19 August 2016 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Sohrabi, Naghmeh (July 2011). "The Power Struggle in Iran: A Centrist Comeback?" (PDF). Middle East Brief (53).

- ↑ Eshkevari, Hasan Yousefi; Mir-Hosseini, Ziba; Tapper, Richard (27 June 2006). "Islam and Democracy in Iran: Eshkevari and the Quest for Reform". I.B.Tauris. Retrieved 19 August 2016 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Mirsepassi, Ali (12 October 2000). "Intellectual Discourse and the Politics of Modernization: Negotiating Modernity in Iran". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 19 August 2016 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 Movahedi, Masood; Siuki, Jafar Fahimi; Shakeri, Mohsen (September 2014). "Analysis of Current Theories on the Development of the Islamic Republic of Iran". Academic Journal of Research in Economics and Management. 2 (9): 42–48. doi:10.12816/0006595. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ↑ Shahibzadeh, Yadullah. Islamism and Post-Islamism in Iran: An Intellectual History. Springer. ISBN 9781137578259. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- 1 2 Ghobadzadeh, Naser; Qubādzādah, Nāṣir (1 December 2014). "Religious Secularity: A Theological Challenge to the Islamic State". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 August 2016 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Surdykowska, Sylwia. Martyrdom and Ecstasy: Emotion Training in Iranian Culture. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781443839532. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ↑ The relation of science and religion according to Motahari, Muhammad hossein mahdavi nejad, magazine of legal investigation, number:6-7, 1381 solar, in persian

- ↑ Bucar, Elizabeth M. Creative Conformity: The Feminist Politics of U.S. Catholic and Iranian Shi'i Women. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 1589017528. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Naderi, Mohammad (July 2014). "PATHOLOGY OF PRESERVATION OF MORALITY IN ISLAMIC AND WESTERN SOCIETIES" (PDF). Kuwait Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review. 3 (11a). Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ lif's outcome, A survey of Morteza Motahari's Ideas.p.455-475.vol.1,1386 solar,Abdullah Nasri

- ↑ life's outcome, A survey of Motahari's Ideas.p.401-410.vol.1,1386 solar

- ↑ Ryaz Ahmaddar,religion and political and social system from Motahari and Iqbal Lahouri, Tolou Magazine, 2007, 21, 6.

- ↑ Shayegan, Darius (1 January 1997). "Cultural Schizophrenia: Islamic Societies Confronting the West". Syracuse University Press. Retrieved 19 August 2016 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi, Abdolkarim Soroush,The Oxford Handbook of Islam and Politics, Edited by John L. Esposito and Emad El-Din Shahin,online pub date: Dec 2013

- ↑ "Martyrdom Anniversary of 'Ayatollah Morteza Motahari' / Pics". AhlulBayt News Agency(ABNA). 3 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- 1 2 Nikazmerad, Nicholas M. (1980). "A Chronological Survey of the Iranian Revolution". Iranian Studies. 13 (1/4): 327–368. doi:10.1080/00210868008701575. JSTOR 4310346.

- ↑ Sahimi, Mohammad (30 October 2009). "The power behind the scene: Khoeiniha". PBS. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ Remembering Ayatollah Morteza Motahari ABNA

- ↑ Farhang Rajaee, Islamism and Modernism: The Changing Discourse in Iran, University of Texas Press (2010), p. 128

- ↑ Farhang Rajaee, Islamism and Modernism: The Changing Discourse in Iran, University of Texas Press (2010), p. 129

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morteza Motahhari. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Morteza Motahhari |

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by None |

President of Council of Islamic Revolution 1979 |

Succeeded by Mahmoud Taleghani |