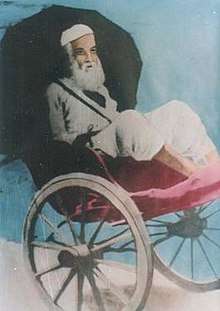

Ashraf Ali Thanwi

| Muhammad Ashraf 'Ali | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

19 August 1863[1] Thana Bhawan |

| Died |

20 July 1943 (aged 79)[2] Thana Bhawan |

| Resting place | Thana Bhawan[2] |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Ethnicity | Indian |

| Era | Modern era |

| Occupation | Islamic scholar |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Sunni islam |

| Jurisprudence | Hanafi |

| Creed | Maturidi |

| Movement | Deobandi |

| Main interest(s) | fiqh, sunni islam, sufism |

| Notable idea(s) | Reformation, Moderation, and Islamisation of every aspect of life, creation of Pakistan, Two-nation theory |

| Notable work(s) | Jamaalu-l-Qur'aan, Bayaanu-l-Qur'aan, Ahkaamu-l-Qur'aan, I'laa as-Sunan, Islaahi Nisaab, Al-Heelatu-nn-Naajizah, Bahishti Zewar, Tarbiyat-s-Saalik, Kaleed-e-Masnavi, etc |

| Alma mater | Darul Uloom Deoband |

| Disciple of | Haji Imdadullah |

|

Influenced by

| |

|

Influenced

| |

| Website |

www |

Muhammad Ashraf 'Ali Thanawi (August 19, 1863 [05 Rabi' al-Thani 1280 AH]) – July 4, 1943 [17 Rajab 1362 AH]) was an Indian Sunni Islamic scholar.

Early life and career

Childhood

Ashraf Ali Thanawi was born on a Wednesday, Fajr time. He was a descendant of Umar from his father's side and a descendant of Ali from his mother's side. He lost his mother at the age of 5 and was raised by his father with special care and attention. His father taught him and his younger brother (Akbar 'Ali) discipline and good character.[2] He loved offering Salah and congregation and abstained from playing with other choldren. He was influenced by his teacher Mawlana Fateh Muhammad Jalandhri in offering Tahajjud and started this act of worship from the tender age of 12 or 13. He also loved Dhikr. He was reprimanded for saying that Mawlana Rafiuddeen Deobandi, the Vice-Chancellor of Darul Uloom Deoband was not much educated.

Education

Thanawi went to Meerut for his early education in basic Persian language and the memorisation of the Qur'aan and then returned to Thana Bhawan and studied elementary Arabic with Mawlana Fateh Muhammad Jalandhari and advanced Persian with his maternal uncle, Mawlana Waajid 'Ali. He then got admitted in Darul Uloom Deoband India in 1295 and studied there for 5 years, graduating in 1301 AH (1884). During his student life, he received special attention from Mawlana Ya'qoob Nanotvi, the Sadr Madaris of Darul Uloom Deoband at that time, Grand Mufti 'Azeezu-R-Rahmaan 'Uthmani, and Mahmud al-Hasan. He was tried and tested by Rashid Ahmad Gangohi at his graduation when he visited Deoband. During his stay at Deoband, he refused invitations from his relatives and abstained from mixing with other students. He was one of the best reciters of the Qur'aan and learned Tajwid and Qira'at from Qāriʾ 'Abdullaah Muhaajir Makki, who was famous amongst the Qāris of Arabia.

Spiritual Reformation

Thanawi wanted to become a disciple of Rasheed Ahmad Gangohi but he was refused as he was still studying. He sent a letter to Haji Imdadullah Muhajir Makki, requesting him to command Rasheed Ahmad Gangohi to accept him as his disci[;e but on reading the letter, Haji Imdadullah became so impressed that he accepted Thanawi as his disciple at the age of 20. Although Haji Imdadullah was his only Shaikh (spiritual mentor), he also visited other Shaikhs like Fadlur-Rahmaan Ganj Moradabadi, Shaah Muhammad Sher Khan, Shah Sulaimaan Lajpuri, Ghulam Muhammad Deenpuri, Taj Muhammad, 'Abdul-Hayy Lucknowi, Mawlana Muhammad na'eem Firangi Mahali, Khaleel Pasha Makki,

Career

After his graduation, Thanawi taught high level books of religious sciences in Faiz-e-Aam Madrasa, Kanpur.[2] Over a short period of time, he acquired a reputable position as a religious scholar of Sufism among other subjects.[3][2][4] His teaching attracted numerous students and his research and publications became well known in Islamic institutions. During these years, he traveled to various cities and villages, delivering lectures in the hope of reforming people. Printed versions of his lectures and discourses usually became available shortly after these tours. Until then, few Islamic scholars had had their lectures printed and widely circulated in their own lifetimes. The desire to reform the masses intensified in him during his stay at Kanpur.[2]

Eventually, Thanwi retired from teaching and devoted himself to reestablishing the spiritual centre (khānqāh) of his shaikh in Thāna Bhāwan.[2]

Fatwa and its refutation

In 1906, Ahmad Raza Khan issued a fatwa against Thanwi and other Deobandi leaders entitled Husam ul-Haramain (Urdu: Sword of Mecca and Medina), decrying them as unbelievers and Satanists. The fatwa was also signed by other scholars including from Hijaz.[5][6][7][8]

The founding scholars of Deoband used to change their names while travelling on trains and other transportation because of threats to their lives due to the fact that their interpretations of Islam had detractors.[9][10]

Political Ideology

Ashraf Ali Thanvi was a strong supporter of the Muslim League.[11] He and his pupils gave their entire support to the demand for the creation of Pakistan.[12] During the 1940s, most Deobandi ulama supported the Congress in contrast to the Barelvi who largely and only supported the Muslim league, although Ashraf Ali Thanvi and some other leading Deobandi scholars including Muhammad Shafi and Shabbir Ahmad Usmani were in favour of the Muslim League.[13][14] Thanvi resigned from Deoband's management committee due to its pro-Congress stance.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ https://sites.google.com/site/islamandthequran/ah-years-converted-to-ad-years, 'Islamic Years Converted to AD years' on the Conversion Chart on google.com website, Retrieved 25 March 2017

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 http://haqislam.org/maulana-ashraf-ali-thanwi/, Profile of Ashraf Ali Thanwi on haqislam.org website, Published 9 November 2014, Retrieved 25 March 2017

- ↑ Ali Abbasi, Shahid. (2008, January–March)

- ↑ Rethinking in Islam: Mawlana Ashraf 'Ali Thanawi on Way and Way-faring. Hamdard Islamic-us, 21(1), 7–23. (Article on Ashraf 'Ali's teachings on Sufism.)

- ↑ http://sufimanzil.org/arabic-fatwa-against-deobandis/, 'Arabic Fatwa against Deobandis', Sufi Manzil website, Published 3 May 2010, Retrieved 25 March 2017

- ↑ Ahmad Raza Khan. Hussam-ul-Harmain

- ↑ Fatawa Hussam-ul-Hermayn by Khan, Ahmad Raza Qadri

- ↑ As-samare-ul-Hindiya by Khan, Hashmat Ali

- ↑ Madsen, Stig Toft; Nielsen, Kenneth Bo; Skoda, Uwe (2011-01-01). Trysts with Democracy: Political Practice in South Asia. Anthem Press. ISBN 9780857287731.

- ↑ Riaz, Ali (2008-01-01). Faithful Education: Madrassahs in South Asia. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813543451.

- ↑ https://www.dawn.com/news/1042583, 'What's wrong with Pakistan?', Dawn newspaper, Published 13 September 2013, Retrieved 25 March 2017

- ↑ Shafique Ali Khan (1988). The Lahore resolution: arguments for and against : history and criticism. Royal Book Co.

- ↑ Ingvar Svanberg; David Westerlund (6 December 2012). Islam Outside the Arab World. Routledge. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-136-11322-2.

- ↑ Rajshree Jetly (27 April 2012). Pakistan in Regional and Global Politics. Taylor & Francis. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-1-136-51696-2.

- ↑ Francis Robinson (2000). "Islam and Muslim separatism.". In John Hutchinson. Nationalism: Critical Concepts in Political Science. Anthony D. Smith. Taylor & Francis. pp. 929–930. ISBN 978-0-415-20112-4.

Further reading

- Zaman, Muhammad Qasim, Ashraf `Ali Thanawi: Islam in Modern South Asia (Makers of the Muslim World), Oneworld, 2007.

- Ahmed, Muniruddin,