Husayn ibn Ali

| Husayn Imam of Muslims | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | الحسين ابن علي |

| Born |

10 October 625 (3 Sha'aban AH 4)[1] Medinah, Hijaz |

| Died |

10 October 680 (aged 55) (10 Muharram AH 61) Karbala, Umayyad section of Mesopotamia |

| Cause of death | Beheaded at the Battle of Karbala |

| Resting place |

His shrine at Karbala, Karbala Governorate, Iraq 32°36′59″N 44°1′56.29″E / 32.61639°N 44.0323028°E |

| Residence | Medinah, Hejaz |

| Known for | being a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the Battle of Karbala,] Imam |

| Title |

List

|

| Term | AC 670–680 |

| Predecessor | (As Shia Imam) Hasan ibn Ali |

| Successor | (As Shia Imam) Ali Zayn al-Abidin |

| Opponent(s) | Yazid ibn Muawiyah |

| Spouse(s) |

Shahr Banu bint Yazdegerd III (last Sassanid Emperor of Persia) Umme Rubāb Umme Laylā |

| Children |

List

|

| Parents | |

| Relatives | |

Al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī ibn Abi Talib (Arabic: الحسين ابن علي ابن أبي طالب; 10 October 625 – 10 October 680) (his name is also transliterated as Husayn ibn Ali, Husain, Hussain and Hussein), was a grandson of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, and son of Ali ibn Abi Talib (the first Shia Imam and the fourth Rashid caliph of Sunni Islam) and Muhammad's daughter, Fatimah. He is an important figure in Islam as he was a member of the Bayṫ (Arabic: بَـيـت, Household) of Muhammad and the Ahl al-Kisā' (Arabic: أَهـل الـكِـسَـاء, People of the Cloak), as well as the third Shia Imam.

Prior to his death, the Umayyad caliph Muawiya appointed his son Yazid as his successor in a clear violation of the Hasan-Muawiya treaty.[8] When Muawiya died in 680 CE, Yazid demanded that Husain pledge allegiance to him. Husain was well-known as the grandson of Muhammad and was an example for many Muslims; if he pledged allegiance to Yazid, who was corrupt, shameless, and tyrannical,[9] it would be seen as legitimizing Yazid's behavior in Islam. Thus, in order to save Islam from Yazid's influence, Husain refused to pledge allegiance to Yazid, even though it meant sacrificing his life. As a consequence, he left Medina, his hometown, to take refuge in Mecca in AH 60.[8][10] There, the people of Kufah sent letters to him, asking his help and pledging their allegiance to him. So he traveled towards Kufah;[8] however, at a place near it known as Karbala, his caravan was intercepted by Yazid's army. He was killed and beheaded in the Battle of Karbala on 10 October 680 (the 10th of Muharram in 61 AH) by Shimr ibn Thil-Jawshan, along with most of his family and companions, including Husayn's six month old son, Ali al-Asghar, with the women and children taken as prisoners.[8][11] Anger at Husayn's death was turned into a rallying cry that helped undermine the Umayyad caliphate's legitimacy, and ultimately overthrow it by the Abbasid Revolution.[12][13]

Husayn is highly regarded by Shia Muslims for refusing to pledge allegiance to Yazid,[14] the Umayyad caliph, because he considered the rule of the Umayyads unjust.[14] The annual memorial for him and his children, family and his companions is the first month in the Islamic calendar, that is Muharram, and the day he was martyred is known as Ashura (the tenth day of Muharram, a day of mourning for Shi'i Muslims). His action at Karbala fueled the later Shia movements.[13] The martyrdom of Husayn was decisive in shaping Islamic and Shia history. The timing of the Imam's life and martyrdom were crucial as they were in one of the most challenging periods of the 7th century. During this time, Umayyad oppression was rampant, and the stand the Imam and his followers took became a symbol of resistance inspiring future uprisings against oppressors.

Family

| Ḥusayn ibn 'Alī | |

|---|---|

Shiism: Imam; Proof of God, The Martyr of Martyrs, Master of the Martyrs All Islam: Ahl al-Bayt, Ṣaḥābī, Martyr; Master of the Youths of Paradise[15] | |

| Venerated in | All Islam (Salafis honour rather than venerate him). |

| Major shrine | Imam Husayn Shrine, Karbala, Iraq |

Husayn's maternal grandmother was Khadijah bint Khuwaylid, and his paternal grandparents were Abu Talib and Fatimah bint Asad. Husayn and Hasan were regarded by Muhammad as his own sons due to his love for them and as they were the sons of his daughter Fatima and he regarded her children as his own children and descendants. He said "Every mother's children are associated with their father except for the children of Fatimah for I am their father and lineage" Thus descendants of Fatimah are descendants of Muhammad, and part of his Bayt.[16][17]

Children:

- Ali Zayn al-'Ābidīn (Arabic: زَيـن الـعَـابِـدِيـن, "Adornment of the Worshipers") (b. AH 36)

- Sakinah (b. AH 38), (Mother:Shahr Banu)

- Ali al-Akbar (b. AH 42)

- Fatimah as-Sughra (b. AH 45) (Mother:Layla)

- Sukaynah (b. AH 56)

- Ali al-Asghar (b. AH 60) (Mother: Rubab)[7]

Birth and early life

Husayn was born on 10 October CE 625 (3 Sha'aban AH 4).[1] However, Shia Hadith state that He was born AH 3.[18] Husayn and his brother Hasan were the last descendants of Muhammad living during his lifetime and remaining after his death. There are many accounts of his love for them which refer to them together.[8] Muhammad is reported to have said that "He who loves me and loves these two, their father and their mother, will be with me at my place on the Day of Resurrection."[19] and that "Hussain is of me and I am of him. Allah loves those who love Hussain. Hussain is a grandson among grandsons."[19] A narration declares Hasan and Husain as the "Masters of the Youth of Paradise"; this has been particularly important for the Shia who have used it in support of the right of Muhammad's descendants to succeed him. The Shi'a maintain that the infallibility of the Imam is a basic rule in the Imamate. "The theologians have defined the Imamate, saying: "Surely the Imamate is a grace from Allah, Who grants it to the most perfect and best of His servants to Him"[20] Other traditions record Muhammad with his grandsons on his knees, on his shoulders, and even on his back during prayer at the moment of prostrating himself, when they were young.[21]

According to Wilferd Madelung, Muhammad loved them and declared them as people of his Bayt very frequently.[22] He has also said: "Every mother's children are associated with their father except for the children of Fatima for I am their father and lineage." Thus, the descendants of Fatimah were descendants of Muhammad, and part of his Bayt.[16] According to popular Sunni belief, it refers to the household of Muhammad. Shia popular view is the members of Muhammad's family that were present at the incident of Mubahalah. According to Muhammad Baqir Majlisi who compiled Bihar al-Anwar, a collection of ahadith (Arabic: أحـاديـث, 'accounts', 'narrations' or 'reports'), Chapter 46 Verse 15 (Al-Ahqaf) and Chapter 89 Verses 27-30 (Al-Fajr) of the Qur'an are regarding Al-Husayn.

The incident of the Mubahalah

In the year AH 10 (AD 631/32) a Christian envoy from Najran (now in southern Saudi Arabia) came to Muhammad to argue which of the two parties erred in its doctrine concerning 'Īsā (Arabic: عِـيـسَى, Jesus). After likening Jesus' miraculous birth to Adam's (Adem) creation,[lower-alpha 1]—who was born to neither a mother nor a father — and when the Christians did not accept the Islamic doctrine about Jesus, Muhammad was instructed to call them to Mubahalah where each party should ask God to destroy the false party and their families.[23][24] "If anyone dispute with you in this matter [concerning Jesus] after the knowledge which has come to you, say: Come let us call our sons and your sons, our women and your women, ourselves and yourselves, then let us swear an oath and place the curse of God on those who lie."[lower-alpha 2][23][25] Sunni historians, except Tabari who do not name the participants, mention Muhammad, Fatimah, Al-Hasan and Al-Husayn as the participants, and some agree with the Shia tradition that 'Ali was among them. Accordingly, in the verse of Mubahalah, in the Shia perspective, the phrase "our sons" would refer to Al-Hasan and Al-Husayn, "our women" would refer to Fatimah, and "ourselves" would refer "'Ali".[23][25]

Life under the first five Caliphs

Mu'awiyah, who was the governor of Ash-Shām (Arabic: اَلـشَّـام)[26][27] under Uthman ibn Affan, had refused Ali's demands for allegiance, and had long been in conflict with him.[28] After Ali was assassinated and people gave allegiance to Hasan, Mu'awiyah prepared to fight with him. The battle led to inconclusive skirmishes between the armies of Hasan and Mu'awiyah. To avoid the agonies of the civil war, Hasan signed a treaty with Mu'awiyah, according to which Mu'awiyah would not name a successor during his reign, and let the Islamic Ummah (Arabic: أُمَّـة, Community) choose his successor.[29]

Husayn and the Umayyad Caliphate

Reign of Muawiyah

According to the Shi'ah, Husayn was the third Imam for a period of ten years after the death of his brother Hasan in CE 669, all of this time but the last six months coinciding with the caliphate of Mu'awiyah.[30] After the peace treaty with Hasan, Mu'awiyah set out with his troops to Kufa, where at a public surrender ceremony Hasan rose and reminded the people that he and Husayn were the only grandsons of Muhammad, and that he had surrendered the reign to Mu'awiyah in the best interest of the community: "O people, surely it was God who led you by the first of us and Who has spared you bloodshed by the last of us. I have made peace with Mu'awiyah, and I know not whether haply this be not for your trial, and that ye may enjoy yourselves for a time."[lower-alpha 3][31] declared Hasan.[29]

In the nine-year period between Hasan's abdication in 41/660 and his death in 49/669, Hasan and Husayn retired in Medina trying to keep aloof from political involvement for or against Muawiyah.[29][32]

Shia feelings, however, though not visible above the surface, occasionally emerged in the form of small groups, mostly from Kufa, visiting Hasan and Husayn asking them to be their leaders - a request to which they declined to respond.[23] Even ten years later, after the death of Hasan, when Iraqis turned to his younger brother, Husayn, concerning an uprising, Husayn instructed them to wait as long as Muawiyah was alive due to Hasan's peace treaty with him.[29] Later on, however, and before his death, Muawiyah named his son Yazid as his successor.[8]

Reign of Yazid

One of the important points of the treaty made between Al-Hasan and Mu'awiyah was that the latter should not designate anyone as his successor after his death. But after the death of Al-Hasan, Mu'awiyah, thinking that no one would be courageous enough to object to his decision as the caliph, designated his son Yazid as his successor in AD 680, breaking the treaty.[33] Robert Payne quotes Mu'awiyah in History of Islam as telling his son Yazid to defeat Al-Husayn – because Mu'awiyah thought he was surely preparing an army against him – but to deal with him gently thereafter as Al-Husayn was a descendant of Muhammad, but to deal with 'Abd Allah ibn al-Zubair swiftly, as Mu'awiyah feared him the most.[34]

In April AD 680, Yazid succeeded his father as caliph. He immediately instructed the governor of Al-Medinah to compel Al-Husayn and few other prominent figures to give their Bay'ah (Arabic: بَـيـعَـة, Pledge of allegiance).[8] Al-Husain, however, refrained from it, believing that Yazid was openly going against the teachings of Islam in public, and changing the sunnah (Arabic: سـنـة, deeds, sayings, etc.) of Muhammad.[35][36] In his view the integrity and survival of the Islamic community depended on the re-establishment of the correct guidance.[37] He, therefore, accompanied by his household, his sons, brothers, and the sons of Al-Hasan, left Al-Medinah to seek asylum in Mecca.[8]

While in Mecca, ibn al-Zubayr, Abdullah ibn Umar and Abdullah ibn Abbas advised Al-Husayn to make Mecca his base, and fight against Yazid from there.[38] On the other hand, the people in Al-Kufah who were informed about Mu'awiyah's death sent letters urging Husayn to join them and pledge to support him against the Umayyads. Al-Husayn wrote back to them saying that he would send his cousin Muslim ibn Aqeel to report to him on the situation. If he found them united as their letters indicated he would speedily join them, because the Imam should act in accordance with the Qur'an, uphold justice, proclaim the truth, and dedicate himself to the cause of God.[8] The mission of Muslim was initially successful, and, according to reports, 18,000 men pledged their allegiance. But the situation changed radically when Yazid appointed 'Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad as the new governor of Al-Kufah, ordering him to deal severely with ibn 'Aqil. Before news of the adverse turn of events arrived in Mecca, Al-Husayn set out for Al-Kufah.[8]

On the way, Al-Husayn found that Muslim was killed in Al-Kufah. He broke the news to his supporters and informed them that people had deserted him. Then, he encouraged anyone who so wished, to leave freely without guilt. Most of those who had joined him at various stages on the way from Mecca now left him.[8]

Martyrdom in the Battle of Karbala

On his path towards Kufah, Al-Husayn encountered the army of Ubaydullah ibn Ziyad. Husayn addressed the Kufans' army, reminding them that they had invited him to come because they were without an Imam. He told them that he intended to proceed to Kufah with their support, but if they were now opposed to his coming, he would return to where he had come from. However, the army urged him to choose another way. Thus, he turned to left and reached Karbala, where the army forced him not to go further, and stop at a location that was without water.[8]

Umar ibn Sa'ad, the head of Kufan army, sent a messenger to Husayn to inquire about the purpose of his coming to Iraq. Husayn answered again that he had responded to the invitation of the people of Kufa but was ready to leave if they now disliked his presence. When Umar ibn Sa'ad, the head of Kufan army reported it back to ibn Ziyad, the governor instructed him to offer Ḥusayn and his supporters the opportunity to swear allegiance to Yazid. He also ordered Umar to cut off Husayn and his followers from access to the water of the Euphrates.[8] On the next morning, as ʿOmar b. Saʿd arranged the Kufan army in battle order, Al-Hurr ibn Yazid al Tamimi challenged him and went over to Al-Ḥusayn. He addressed the Kufans in vain, rebuking them for their treachery to the grandson of Muhammad, and was killed in the battle.[8]

The Battle of Karbala lasted from morning till sunset of 10 October 680 (Muharram 10, AH 61). All of Al-Husayn's small army of companions fought with a large army under the command of Umar ibn Sa'ad, and were killed near the river (Euphrates) from which they were not allowed to get any water. In total, around 72 men, and a few ladies and children, had been on the side of Al-Husayn.[40][41][42] The renowned historian Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī stated "… then fire was set to their camp and the bodies were trampled by the hoofs of the horses; nobody in the history of the human kind has seen such atrocities."[43]

Aftermath

Once the Umayyad troops had massacred Al-Husayn and his male soldiers, they looted the tents, stripped the women of their jewellery, and took the skin upon which Ali Zainal-Abidin was prostrate. Ali had been unable to fight in the battle, due to an illness.[40][41][42] It is said that Shimr was about to kill him, but Husayn's sister Zaynab was able to convince his commander, Umar, to let him live. Zaynul-Abidin and other relatives of Husayn were taken hostage. They were taken to meet Yazid in Damascus, and eventually, they were allowed to return to Al-Medinah.[44][45]

After learning of the martyrdom of Husayn, ibn al-Zubayr collected the people of Mecca and made the following speech:

O people! No other people are worse than Iraqis and among the Iraqis, the people of Kufa are the worst. They repeatedly wrote letters and called Imam Husayn to them and took bay'at (allegiance) for his caliphate. But when ibn Ziyad arrived in Kufa, they rallied around him and killed Imam Husayn who was pious, observed the fast, read the Quran and deserved the caliphate in all respects[46]

After his speech, the people of Mecca joined him to take on Yazid. When he heard about this, Yazid had a silver chain made and sent to Mecca with the intention of having Walid ibn Utbah arrest Ibn al-Zubair with it[46] Eventually ibn al-Zubayr consolidated his power by sending a governor to Kufah. Soon, he established his power in Iraq, southern Arabia, the greater part of Al-Sham, and parts of Egypt. Yazid tried to end his rebellion by invading the Hijaz, and took Medina after the bloody Battle of al-Harrah followed by the siege of Mecca but his sudden death ended the campaign and threw the Umayyads into disarray with civil war eventually breaking out. This essentially split the Islamic empire into two spheres with two different caliphs, but soon the Umayyad civil war was ended, and he lost Egypt and whatever he had of Al-Sham to Marwan. This coupled with the Kharijite rebellions in Iraq reduced his domain to only the Hijaz. In Mecca and Medinah, Husayn's family had a strong support base and the people were willing to stand up for them. However, Husayn's remaining family moved back to Al-Medinah. Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr was the grandson of Abu Bakr and the cousin of Qasim ibn Muhammad ibn Abu Bakr. Both Abdullah and Qasim were Aisha's nephews. Qasim was also the grandfather of Imam Jafar al-Sadiq. Ibn al-Zubayr was finally defeated and killed by Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, who was sent by Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, on the battlefield in AD 692. He beheaded him and crucified his body, reestablishing Umayyad control over the Empire.

Yazid reportedly died in Rabi'al-Awwal, 64 AH (November, AD 683), less than 4 years after coming to power.[8][47] As for other opponents of Al-Husayn, such as ibn Ziyad and Shimr, they were killed in a rebellion led by a vengeful contemporary of Husayn known as "Mukhtar al-Thaqafi."[48][49][50][51]

Years later, the people of Kufah called upon Zayd ibn Ali ibn Al-Husayn to come over. Zaydis believe that on the last hour of Zayd, Zayd was also betrayed by the people in Kufah who said to him: "May God have mercy on you! What do you have to say on the matter of Abu Bakr and Umar ibn al-Khattab?" Zayd said, "I have not heard anyone in my family renouncing them both nor saying anything but good about them...when they were entrusted with government they behaved justly with the people and acted according to the Qur'an and the Sunnah."[52][53][54][55]

Burial

Husayn's body is buried in Karbala, the site of his death. His head is said to have been returned from Damascus and interred with his body,[56] although various sites have also been claimed to house Husayn's head, among others: Aleppo, Ashkelon, Baalbek, Damascus, Homs, Merv, and Medina.[57]

Return of his head to the body

Husayn's son Ali returned his head from Ash-Sham[26][27] to Karbala,[58][59][60][61] forty days after Ashura, reuniting it with Husayn's body.[62][63] Shi'a Muslims commemorate this fortieth day as Arba‘īn.[64][65][66][67] According to the Shia belief that the body of an Imam is only buried by an Imam,[68][69][70] Husayn ibn Ali's body was buried by his son, Ali Ibn Husayn.[71]

Husayn's head in Isma'ilism

When the Abbasids took power from the Umayyads, in the garb of taking revenge of Ahl al-Bayt, they also confiscated the head of Husayn and proved to be worse enemies than the Umayyads. The Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadir (d. 295/908) attempted many times to stop the pilgrimage to the head but in vain. He thus tried to completely eliminate the sign of the sacred place of Ziyarat; he transferred the head of Husayn to Ashkelon in secrecy, so that pilgrims could not find the place.[72] According to an Arabic inscription, which is still preserved on the Fatimid-era minbar,[73] the Fatimid vizier Badr al-Jamali rediscovered the head and constructed a shrine around it.[57][74] The shrine was described as the most magnificent building in Ashkelon.[75] In the British Mandate period it was a "large maqam on top of a hill" with no tomb but a fragment of a pillar showing the place where the head had been buried.[76] Israeli Defense Forces under Moshe Dayan blew up Mashhad Nabi Hussein in July 1950 as part of a broader operation.[77] Around the year 2000, Isma'ilis from India built a marble platform there, on the grounds of the Barzilai Medical Center.[78][79][77] The head remained in Ashkelon only until Crusaders arrived, upon which it was taken to Cairo where Al-Hussein Mosque became its final resting place.[79]

Commemoration

The Day of Ashura is commemorated by the Shia society as a day of mourning for the death of Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of Muhammad, at the Battle of Karbala. The commemoration of Husayn ibn Ali has become a national holiday and different ethnic and religious communities participate in it.

Al-Husayn's grave became the most visited place of Ziyarat for Shias. Some said that a pilgrimage to Karbala and Husayn's shrine therein has the merit of a thousand pilgrimages to Mecca, of a thousand martyrdoms, and of a thousand days fasting.[80] Shia have an important book about Al-Husayn which is called Ziyarat Ashura. Most of them believe that it is a Hadith-e-Qudsi (the "word of Allah").[81][82] The Imam Husayn Shrine was later built over his grave. In 850 Abbasid caliph, al-Mutawakkil, destroyed his shrine in order to stop Shia pilgrimages. However, pilgrimages continued.[83]

Shias mourn during Muharram to pay respect to Husayn whose sacrifices kept true Islam alive and to show their allegiance and love for Imamate. Many Christians and Sunnis also join them in their Mourning of Muharram. [84]

Views on Husayn

The effect of the events in Karbala on Muslims has been deep and is beyond passion in Shiʿism. While the intent of the major players in the act has often been debated, it is clear that Husayn cannot be viewed as simply a rebel risking his and his family's lives for his personal ambition. He continued to abide by the treaty with Muawiyah I despite his disapproval of Muawiyah's conduct. He did not pledge allegiance to Yazid, who had been chosen as successor by Muawiyah in violation of the treaty with Hasan ibn Ali. Yet he also did not actively seek martyrdom and offered to leave Iraq once it became clear that he no longer had any support in Kufa. His initial determination to follow the invitation of the Kufans in spite of the numerous warnings he received depicts a religious conviction of a mission that left him no choice, whatever the outcome. He is known to have said:

...Dying with honor is better than living with dishonor[85]

In culture

Historian Edward Gibbon was touched by the story of Al-Husayn, describing the events at Karbala as "a tragedy".[86][87] According to historian Syed Akbar Hyder, Mahatma Gandhi attributed the historical progress of Islam, to the "sacrifices of Muslim saints like Husayn" rather than military force.[88]

The traditional narration "Every day is Ashura and every land is Karbala!" is used by the Shia as a mantra to live their lives as Husayn did on Ashura, i.e. with complete sacrifice for God and for others. The saying is also intended to signify that what happened on Ashura in Karbala must always be remembered as part of suffering everywhere.

Inspiring modern movements

The story of martyrdom of Husayn has been a strong source of inspiration for Shia revolutionary movements. For Shias, Husayn's willing martyrdom justifies their own resistance against unjust authority. In the course of the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran against Pahlavi dynasty, Shia beliefs and symbols were instrumental in orchestrating and sustaining widespread popular resistance with the Husayn legend providing a framework for labeling as evil and reacting against the Pahlavi Shah.[89]

Selected sayings

The following sentences belonge to Husayn ibn Ali:

- "The most generous people are those who do kindness when it is least expected."[90]

- "Knowledge facilitates comprehension and experience increases wisdom."[91]

- "Patience in a person glows like a jewel."[92]

- "The true life is all having a strong idea and striving (for that idea)"[93][93]

- "If you do not believe in any religion, and do not fear the Day of Resurrection, then at least be free in this world."[94][93]

See also

![]()

- Family tree of Muhammad#Family tree linking prophets to Imams

- List of casualties in Husayn's army at the Battle of Karbala'

- Sayyid

- Arba'een Pilgrimage

- Zulfiqar

- Zuljanah

- Holiest sites in Islam (Shia)

- Shi'a view of the Sahaba

- Sunni view of the Sahaba

- Sayyed Ibn Tawus

- Who is Hussain?

- The martyrs of al-Ukhdûd (Arabic: الأُخـدُود, "the Ditch", or a place near Najran)

- Al-Tall Al-Zaynabiyya

Notes

Footnotes

- 1 2 Shabbar, S.M.R. (1997). Story of the Holy Ka'aba. Muhammadi Trust of Great Britain. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ Nakash, Yitzhak (1 January 1993). "An Attempt To Trace the Origin of the Rituals of Āshurā¸". Die Welt des Islams. 33 (2): 161–181. doi:10.1163/157006093X00063. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 al-Qarashi, Baqir Shareef (2007). The life of Imam Husain. Qum: Ansariyan Publications. p. 58.

- ↑ Tirmidhi, Vol. II, p. 221 ; تاريخ الخلفاء، ص189 [History of the Caliphs]

- ↑ A Brief History of The Fourteen Infallibles. Qum: Ansariyan Publications. 2004. p. 95.

- ↑ Kitab al-Irshad. p. 198.

- 1 2 S. Manzoor Rizvi. The Sunshine Book. books.google.com. ISBN 1312600942.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Madelung, Wilferd. "HOSAYN B. ALI". Iranica. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- ↑ "Yazid son of Mu'awiyah". Al-Islam.org. Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Gordon, 2005, pp. 144–146.

- ↑ Cornell, Vincent J.; Kamran Scot Aghaie (2007). Voices of Islam. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. pp. 117 and 118. ISBN 9780275987329. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- 1 2 Robinson, Chase F (2010). "5 - The rise of Islam, 600–705". In Chase F. Robinson. The new Cambridge history of Islam, volume 1: Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 215. ISBN 9780521838238.

- 1 2 "al-Hussein ibn 'Ali". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Present in both Sunni and Shia sources on basis of the hadith: "al-Ḥasan and al-Ḥusayn are the sayyids of the youth of Paradise".

- 1 2 Suyyuti, Jalayeddin. Kanz-ol-Ommal. pp. 152:6.

- ↑ https://www.al-islam.org/virtues-sayyidah-fatimah-sa-dr-muhammad-tahir-ul-qadri/28-children-fatimah-sa-are-children-prophet

- ↑ Thiqatu Al-Islam, Abu Ja'far (2015). Al-Kafi Volume 1 (Second ed.). New York: The Islamic Seminary. p. 468.

- 1 2 Al-Sibai, Amal (30 October 2015). "Murder of the grandson of the Prophet". Saudi Gazette. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ↑ Sharif al-Qarashi, Baqir (2005). The Life of Imam Musa bin Ja'far al-Kazim. Translated by al-Rasheed, Jasim (1st ed.). Qom, Iran: Ansariyan Publications. p. 98. ISBN 978-9644386398.

- ↑ L. Veccia Vaglieri, (al-) Ḥusayn b. ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib, Encyclopedia of Islam.

- ↑ Madelung (1997), pp. 14–16.

- 1 2 3 4 Momen, Moojan (1985). An Introduction to Shi'i Islam. Yale University Press. p. 14,26,27. ISBN 978-0-300-03531-5.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 15–16.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 16.

- 1 2 Article "AL-SHĀM" by C.E. Bosworth, Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume 9 (1997), page 261.

- 1 2 Kamal S. Salibi (2003). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. I.B.Tauris. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-1-86064-912-7.

To the Arabs, this same territory, which the Romans considered Arabian, formed part of what they called Bilad al-Sham, which was their own name for Syria. From the classical perspective, however, Syria, including Palestine, formed no more than the western fringes of what was reckoned to be Arabia between the first line of cities and the coast. Since there is no clear dividing line between what is called today the Syrian and Arabian deserts, which actually form one stretch of arid tableland, the classical concept of what actually constituted Syria had more to its credit geographically than the vaguer Arab concept of Syria as Bilad al-Sham. Under the Romans, there was actually a province of Syria, with its capital at Antioch, which carried the name of the territory. Otherwise, down the centuries, Syria like Arabia and Mesopotamia was no more than a geographic expression. In Islamic times, the Arab geographers used the name arabicized as Suriyah, to denote one special region of Bilad al-Sham, which was the middle section of the valley of the Orontes river, in the vicinity of the towns of Homs and Hama. They also noted that it was an old name for the whole of Bilad al-Sham which had gone out of use. As a geographic expression, however, the name Syria survived in its original classical sense in Byzantine and Western European usage, and also in the Syriac literature of some of the Eastern Christian churches, from which it occasionally found its way into Christian Arabic usage. It was only in the nineteenth century that the use of the name was revived in its modern Arabic form, frequently as Suriyya rather than the older Suriyah, to denote the whole of Bilad al-Sham: first of all in the Christian Arabic literature of the period, and under the influence of Western Europe. By the end of that century it had already replaced the name of Bilad al-Sham even in Muslim Arabic usage.

- ↑ "Alī ibn Abu Talib". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Jafri, Syed Husain Mohammad (2002). The Origins and Early Development of Shi'a Islam; Chapter 6. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195793871.

- ↑ Tabatabaei, (1979), p.196.

- ↑ Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). The Shi'ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Irak. BURLEIGH PRESS. pp. 66–78.

- ↑ Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. pp. 324–327. ISBN 0-521-64696-0.

- ↑ Halm (2004), p.13.

- ↑ John Dunn, The Spread of Islam, pg. 51. World History Series. San Diego: Lucent Books, 1996. ISBN 1560062851

- ↑ Al Bidayah wa al-Nihayah

- ↑ Al-Sawa'iq al-Muhriqah

- ↑ Dakake (2007), pp. 81 and 82.

- ↑ Balyuzi, H. M.: Muhammad and the course of Islam. George Ronald, Oxford (U.K.), 1976, p.193.

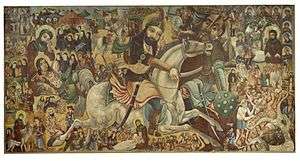

- ↑ "Brooklyn Museum: Arts of the Islamic World: Battle of Karbala". Brooklyn, New York: Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- 1 2 Hoseini-e Jalali, Mohammad-Reza (1382). Jehad al-Imam al-Sajjad (in Persian). Translated by Musa Danesh. Iran, Mashhad: Razavi, Printing & Publishing Institute. pp. 214–217.

- 1 2 "در روز عاشورا چند نفر شهید شدند؟". Archived from the original on 26 March 2013.

- 1 2 "فهرست اسامي شهداي كربلا". Velaiat.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ Chelkowski, Peter J. (1979). Ta'ziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran. New York. p. 2.

- ↑ Madelung, Wilferd. "ʿALĪ B. ḤOSAYN B. ʿALĪ B. ABĪ ṬĀLEB". ENCYCLOPÆDIA IRANICA. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ↑ Donaldson, Dwight M. (1933). The Shi'ite Religion: A History of Islam in Persia and Irak. BURLEIGH PRESS. pp. 101–111.

- 1 2 Najeebabadi, Akbar Shah (2001). The History of Islam V.2. Riyadh: Darussalam. pp. 110. ISBN 9960892883.

- ↑ Bosworth, C.E. (1960). "Muʿāwiya II". In Bearman, P. Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. ISBN 9789004161214.

- ↑ "al-Mukhtār ibn Abū ʿUbayd al-Thaqafi". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ al-Syyed, Kamal. "The Battle of al-Khazir". Mukhtar al-Thaqafi. Qum, Iran: Ansariyan Foundation. p. 21. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ Al-Kashee, Ikhtiyaar Ma`arifah Al-Rijaal, pg. 127, hadeeth # 202.

- ↑ Al-Khoei, Mu`jam Rijaal Al-Hadeeth, vol. 18, pg. 93, person # 12158.

- ↑ Islam re-defined: an intelligent man's guide towards understanding Islam - Page 54

- ↑ Abou El Fadl, Khaled (2006). Rebellion and Violence in Islamic Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780521030571.

- ↑ The waning of the Umayyad caliphate by Tabarī, Carole Hillenbrand, 1989, p37, p38.

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Religion Vol.16, Mircea Eliade, Charles J. Adams, Macmillan, 1987, p243. "They were called "Rafida by the followers of Zayd".

- ↑ Halm (2004), pp. 15 and 16.

- 1 2 Williams, Caroline. 1983. "The Cult of 'Alid Saints in the Fatimid Monuments of Cairo. Part I: The Mosque of al-Aqmar". In Muqarnas I: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Oleg Grabar (ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press, 37-52. p.41, Wiet,"notes," pp.217ff.; RCEA,7:260-63.

- ↑ Amali of Shaykh Sadouq, Majlis 31, p. 232.

- ↑ Fattāl Nayshābūrī. Rawḍat al-Wāʿiẓīn. p. 192.

- ↑ Muhammad Baqir Majlisi. Bihar al-Anwar. 45 p=140.

- ↑ Sharif al-Murtaza. Rasā’il. 3. p. 130.

- ↑ Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī. The Remaining Signs of Past Centuries. p. 331.

- ↑ Zakariya al-Qazwini. ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā'ib al-mawjūdāt. p. 45.

- ↑ Ibn Shahrashub. Manāqib Āl Abī-Ṭālib. 4. p. 85.

- ↑ Al-Qurtubi. al-Tadhkirah fī Aḥwāl al-Mawtā wa-Umūr al-Ākhirah. 2. p. 668.

- ↑ Ibn Tawus. Luhūf. p. 114.

- ↑ Ibn Namā al-Ḥillī. Muthīr al-Aḥzān. p. 85.

- ↑ Osul-al-Kafi, Vol 1. pp. 384, 385.

- ↑ Ithbat-ol-Wasiyah. pp. 207, 208.

- ↑ Ikhtiar Ma'refat-o-Rijal. pp. 463–465.

- ↑ باقر شريف قرشى. حياة الإمام الحسين عليه السلام, Vol 3. Qom, Iran (published in AH 1413): مدرسه علميه ايروانى. p. 325.

- ↑ Brief History of Transfer of the Sacred Head of Hussain ibn Ali, From Damascus to Ashkelon to Qahera By: Qazi Dr. Shaikh Abbas Borhany PhD (USA), NDI, Shahadat al A'alamiyyah (Najaf, Iraq), M.A., LLM (Shariah) Member, Ulama Council of Pakistan. Published in Daily News, Karachi, Pakistan on 3 January 2009.

- ↑ File:Inscription on mimbar Ibrahimi mosque.JPG

- ↑ Safarname Ibne Batuta.

- ↑ Moshe Gil, A History of Palestine, 634–1099 (1997) p 193–194.

- ↑ Taufik Canaan (1927). Mohammedan Saints and Sanctuaries in Palestine. London: Luznac & Co. p. 151.

- 1 2 Rapoport, Meron (5 July 2007). "History Erased". Haaretz.

- ↑ Sacred Surprise behind Israel Hospital, by Batsheva Sobelman, special Los Angeles Times.

- 1 2 ; Prophet's grandson Hussein honoured on grounds of Israeli hospital

- ↑ Braswell, Islam: Its Prophet, Peoples, Politics and Power,1996, p.28.

- ↑ Al Muntazar University of Islamic Studies. "Ziyarat Ashoora - Importance, Rewards and Effects". Duas. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ↑ Azizi Tehrani, Ali Asghar (15 November 2015). The Torch of Perpetual Guidance, an Expose on Ziyarat Ashura of al-Imam al-Husain (PDF). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1519308160.

- ↑ Halm (2004), p. 15.

- ↑ ; who-was-hussein-and-why-..

- ↑ Ibn Shahr Ashoub. Manabiq Al Abi Talib, Vol 4. p. 68.

- ↑ Cole, Juan. "Barack Hussein Obama, Omar Bradley, Benjamin Franklin and other Semitically Named American Heroes". Informed Comment.

- ↑ "In a distant age and climate, the tragic scene of the death of Husein will awaken the sympathy of the coldest reader." The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vol. 2, p. 218.

- ↑ Reliving Karbala: Martyrdom in South Asian memory, By Syed Akbar Hyder, Oxford University Press, p. 170.

- ↑ Skocpol, Teda. "Rentier state and Shi'a Islam in the Iranian Revolution (Chapter 10) - Social Revolutions in the Modern World". Cambridge Core. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ Muhammadi Reishahri, Muhammad (2010). Mizan al-Hikmah. 2. Qum: Dar al-Hadith. p. 390.

- ↑ Muhammadi Reishahri, Muhammad (2010). Mizan al-Hikmah. 2. Qum: Dar al-Hadith. p. 186.

- ↑ Muhammadi Reishahri, Muhammad (2010). Mizan al-Hikmah. 3. Qum: Dar al-Hadith. p. 217.

- 1 2 3 Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project Team. "A Shi'ite Encyclopedia". al-islam. Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project.

- ↑ Muhammad Baqir Majlisi. Bihar al-Anwar. 45. p. 51.

References

- Books

- Al-Bukhari, Muhammad Ibn Ismail (1996). The English Translation of Sahih Al Bukhari With the Arabic Text, translated by Muhammad Muhsin Khan. Al-Saadawi Publications. ISBN 1-881963-59-4.

- Canaan, Tawfiq (1927). Mohammedan Saints and Sanctuaries in Palestine. London: Luzac & Co.

- Dakake, Maria Massi (2007). The Charismatic Community: Shi'ite Identity in Early Islam. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-7033-4.

- Gordon, Matthew (2005). The Rise Of Islam. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32522-7.

- Halm, Heinz; Janet Watson; Marian Hill (2004). Shi'ism. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1888-0.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64696-0.

- Tabatabae; Sayyid Mohammad Hosayn (translator) (1979). Shi'ite Islam. Suny Press. ISBN 0-87395-272-3.

- Encyclopedia

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- Encyclopædia Iranica. Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University. ISBN 1-56859-050-4.

- Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an. Brill Publishers, Leiden. ISBN 90-04-14743-8.

- Encyclopaedia of Islam.

- Blog

- Sacred Surprise behind Israel Hospital, by Batsheva Sobelman, special Los Angeles Times

External links

- Hussein ibn 'Ali an article of Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Biography of Imam Husayn on YouTube

- Hussein ibn 'Ali by Wilferd Madelung, an article of Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Hussein ibn 'Ali in popular Shiism by Jean Calmard, an article of Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Imam Hussein in the eyes of non-Muslims

- The Third Imam

- Martyr Of Karbala

- An account of the death of Husayn ibn Ali

- Interactive Family Tree by Happy Books

- Story of Karbala: Maqtal e Abi Mukhnaf

- Brief History of Transfer of the Sacred Head of Hussain ibn Ali, From Damascus to Ashkelon to Qahera By Qazi Dr. Shaikh Abbas Borhany PhD (USA), NDI, Shahadat al A'alamiyyah (Najaf, Iraq), M.A., LLM (Shariah) Member, Ulama Council of Pakistan. Published in Daily News, Karachi, Pakistan on 3 January 2009.

Husayn ibn Ali of the Ahl al-Bayt Clan of the Quraish Born: 3 Sha'bān AH 4 in the ancient (intercalated) Arabic calendar 10 October AD 625 Died: 10 Muharram AH 61 10 October AD 680 | ||

| Shia Islam titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Hasan ibn Ali Disputed by Nizari |

2nd Imam of Ismaili Shia 3rd Imam of Sevener, Twelver, and Zaydi Shia 669–680 |

Succeeded by 'Alī ibn Ḥusayn |

| Succeeded by Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyyah Kaysanites successor | ||

.jpg)