Islamic calligraphy

|

| Calligraphy |

|---|

Islamic calligraphy is the artistic practice of handwriting and calligraphy, based upon the alphabet in the lands sharing a common Islamic cultural heritage. It includes Arabic Calligraphy, Ottoman, and Persian calligraphy.[1][2] It is known in Arabic as khatt Islami (خط اسلامي), meaning Islamic line, design, or construction.[3]

The development of Islamic calligraphy is strongly tied to the Qur'an; chapters and excerpts from the Qur'an are a common and almost universal text upon which Islamic calligraphy is based. Deep religious association with the Qur'an, as well as suspicion of figurative art as idolatrous, has led calligraphy to become one of the major forms of artistic expression in Islamic cultures.[1] It has also been argued that Islamic calligraphy was motivated less by iconophobia (since, in fact, images were by no means absent in Islamic art) than by the centrality of the notion of writing and written text in Islam.[4] It is noteworthy, for instance, that the Prophet Muhammad is related to have said: "The first thing God created was the pen."[5]

As Islamic calligraphy is highly venerated, most works follow examples set by well established calligraphers, with the exception of secular or contemporary works. In antiquity, a pupil would copy a master's work repeatedly until their handwriting was similar. The most common style is divided into angular and cursive, each further divided into several sub-styles.[2]

Instruments and media

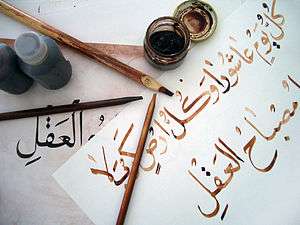

The traditional instrument of the Islamic calligrapher is the qalam, a pen normally made of dried reed or bamboo; the ink is often in color, and chosen such that its intensity can vary greatly, so that the greater strokes of the compositions can be very dynamic in their effect. Some styles are often written using a metallic-tip pen.

1. Naskh (نسخ nasḫ)

2. Nasta‘liq (نستعلیق nastaʿlīq)

3. Diwani (ديواني dīwānī)

4. Thuluth (ثلث ṯuluṯ)

5. Ruq‘ah (رقعة ruqʿah)

Islamic calligraphy is applied on a wide range of decorative mediums other than paper, such as tiles, vessels, carpets, and inscriptions.[2] Before the advent of paper, papyrus and parchment were used for writing. The advent of paper revolutionized calligraphy. While monasteries in Europe treasured a few dozen volumes, libraries in the Muslim world regularly contained hundreds and even thousands of books.[1]:218

Coins were another support for calligraphy. Beginning in 692, the Islamic caliphate reformed the coinage of the Near East by replacing visual depiction with words. This was especially true for dinars, or gold coins of high value. Generally the coins were inscribed with quotes from the Qur'an.

By the tenth century, the Persians, who had converted to Islam, began weaving inscriptions onto elaborately patterned silks. So precious were calligraphic inscribed textiles that Crusaders brought them to Europe as prized possessions. A notable example is the Suaire de Saint-Josse, used to wrap the bones of St. Josse in the Abbey of St. Josse-sur-Mer near Caen in northwestern France.[1]:223–5

Styles

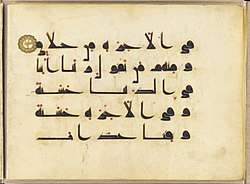

Kufic

Kufic is the oldest form of the Arabic script. The style emphasizes rigid and angular strokes, which appears as a modified form of the old Nabataean script. The Archaic Kufi consisted of about 17 letters without diacritic dots or accents. Afterwards, dots and accents were added to help readers with pronunciation, and the set of Arabic letters rose to 28.[6] It is developed around the end of the 7th century in the areas of Kufa, Iraq, from which it takes its name.[7] The style later developed into several varieties, including floral, foliated, plaited or interlaced, bordered, and squared kufi. It was the main script used to copy Qur'ans from the 8th to 10th century and went out of general use in the 12th century when the flowing naskh style become more practical, although it continued to be used as a decorative element to contrast superseding styles.[8]

There were no set rules of using the Kufic script; the only common feature is the angular, linear shapes of the characters. Due to the lack of methods, the scripts in different regions and countries and even down to the individuals themselves have different ways to write in the script creatively, ranging from very square and rigid forms to flowery and decorative.[7]

Common varieties include[7] square Kufic, a technique known as banna'i.[9] Contemporary calligraphy using this style is also popular in modern decorations.

Decorative kufic inscriptions are often imitated into pseudo-kufics in Middle age and Renaissance Europe. Pseudo-kufics is especially common in Renaissance depictions of people from the Holy Land. The exact reason for the incorporation of pseudo-Kufic is unclear. It seems that Westerners mistakenly associated 13–14th century Middle-Eastern scripts as being identical with the scripts current during Jesus's time, and thus found natural to represent early Christians in association with them.[10]

Naskh

.jpg)

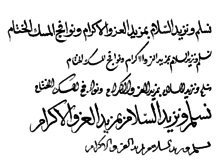

The use of cursive script coexisted with kufic, but because in the early stages of their development they lacked discipline and elegance, cursive were usually used for informal purposes.[11] With the rise of Islam, new script was needed to fit the pace of conversions, and a well defined cursive called naskh first appeared in the 10th century. The script is the most ubiquitous among other styles, used in Qur'ans, official decrees, and private correspondence.[12] It became the basis of modern Arabic print.

Standardization of the style was pioneered by Ibn Muqla (886 – 940 A.D.) and later expanded by Abu Hayan at-Tawhidi (died 1009 A.D.) and Muhammad Ibn Abd ar-Rahman (1492 – 1545 A.D.). Ibn Muqla is highly regarded in Muslim sources on calligraphy as the inventor of the naskh style, although this seems to be erroneous. However, Ibn Muqla did establish systematic rules and proportions for shaping the letters, which use 'alif as the x-height.[13]

Variation of the naskh includes:

- Thuluth is developed as a display script to decorate particular scriptural objects. Letters have long vertical lines with broad spacing. The name, meaning "third", is in reference to the x-height, which is one third of the 'alif.[3]

- Riq'ah is a handwriting style derived from naskh and thuluth, first appeared in the 9th century. The shape is simple with short strokes and little flourishes.[3]

- Muhaqqaq is a majestic style used by accomplished calligraphers. It was considered one of the most beautiful scripts, as well as one of the most difficult to execute. Muhaqqaq was commonly used during the Mameluke era, but the use become largely restricted to short phrases, such as the basmallah, from the 18th century onward.[14]

Regional styles

With the spread of Islam, the Arabic script was established in a vast geographic area with many regions developing their own unique style. From the 14th century onward, other cursive styles began to developed in Turkey, Persia, and China.[12]

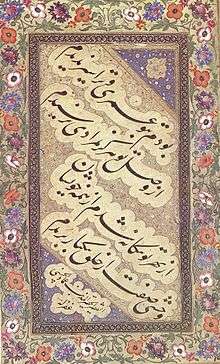

- Nasta'liq is a cursive style originally devised to write the Persian language for literary and non-Qur'anic works.[7] Nasta'liq is thought to be a later development of the naskh and the earlier ta'liq script used in Iran.[15] The name ta'liq means "hanging", and refers to the slightly steeped lines of which words run in, giving the script a hanging appearance. Letters have short vertical strokes with broad and sweeping horizontal strokes. The shapes are deep, hook-like, and have high contrast.[7] A variant called Shikasteh is used in a more informal contexts.

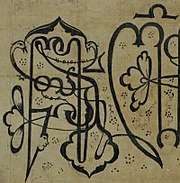

- Diwani is a cursive style of Arabic calligraphy developed during the reign of the early Ottoman Turks in the 16th and early 17th centuries. It was invented by Housam Roumi and reached its height of popularity under Süleyman I the Magnificent (1520–1566).[16] Spaces between letters are often narrow, and lines ascend upwards from right to left. Larger variations called djali are filled with dense decorations of dots and diacritical marks in the space between, giving it a compact appearance. Diwani is difficult to read and write due to its heavy stylization, and became ideal script for writing court documents as it ensured confidentiality and prevented forgery.[7]

- Sini is a style developed in China. The shape is greatly influenced by Chinese calligraphy, using a horsehair brush instead of the standard reed pen. A famous modern calligrapher in this tradition is Hajji Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang.[17]

Modern

In the post colonial era, artists working in North Africa and the Middle East transformed Arabic calligraphy into a modern art movement, known as the Hurufiyya movement. [18] Also known as the Al-hurufiyyah movement or the North African Letterist movement, artists working in this field use calligraphy as a graphic form within a contemporary artwork. [19]

The term, hurifiyya is derived from the Arabic term, harf for letter. Traditionally, the term was charged with Sufi intellectual and esoteric meaning. [20] It is an explicit reference to a Medieval system of teaching involving political theology and lettrism. In this theology, letters were seen as primordial signifiers and manipulators of the cosmos. [21]

Hurufiyya artists rejected Western art concepts, and instead grappled with a new artistic identity drawn from within their own culture and heritage. These artists successfully integrated Islamic visual traditions, especially calligraphy, into contemporary, indigenous compositions. [22] Although hurufiyyah artists struggled to find their own individual dialaogue with nationalism, they also worked towards an aesthetic that transcended national boundaries and represented a broader affiliation with an Islamic identity. [23]

The hurufiyya art movement probably began in North Africa around 1955, in the area around Sudan, with the work of Ibrahim el-Salahi. [24] However, the use of calligraphy in modern artworks appears to have emerged independently in various Islamic states. Few of the artists working in this field, had knowledge of each other, allowing for different manifestations of hurufiyyah to emerge in different regions. [25] In Sudan, for instance, artworks include both Islamic calligraphy and West African motifs. [26]

Leading exponents of hurufiyyah art can be found in Jordan. [27] The Jordanian artist and art historian, Princess Wijdan Ali, for example, who revived the traditions of Arabic calligraphy in a modern, abstract, format. [28]

The hurufiyyah art movement was not confined to painters, but also included artists working in a variety of media, such as the Jordanian ceramicist, Mahmoud Taha, who combined traditional aesthetics, including calligraphy, with skilled craftsmanship [29] Nor was the movement confined to Jordan. In Iraq, the movement was known as Al Bu'd al Wahad (or the One Dimension Group)",[30] and in Iran, it was known as the Saqqa-Khaneh movement. [31]

Western art has influenced Arabic calligraphy in other ways, with forms such as calligraffiti; the use of calligraphy in public art to make politico-social messages or to vandalise public buildings and spaces. [32] Notable Islamic calligraffiti artists include: Yazan Halwani active in Lebanon, [33] and A1one in Tehran and Middle East. [34]

Gallery

Kufic

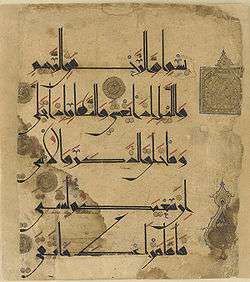

Kufic script in an 11th-century Qur'an

Kufic script in an 11th-century Qur'an Maghribi kufic script in a 13th-century Qur'an

Maghribi kufic script in a 13th-century Qur'an Square kufic tilework in Yazd, Iran

Square kufic tilework in Yazd, Iran Under-glaze terracotta bowl from the 11th century Nishapur

Under-glaze terracotta bowl from the 11th century Nishapur Gold dinar from 10th century Syria

Gold dinar from 10th century Syria A Kufic calligraphy in Chota Imambara

A Kufic calligraphy in Chota Imambara

Naskh

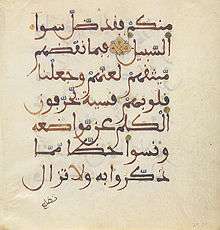

Muhaqqaq script in a 15th-century Qur'an from Turkey.

Muhaqqaq script in a 15th-century Qur'an from Turkey..tif.jpg) Muhaqqaq script in a 13th-century Qur'an.

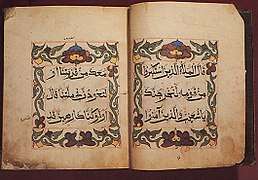

Muhaqqaq script in a 13th-century Qur'an. Naskh script in an early 16th-century Ottoman manuscript dedicated to Selim I.

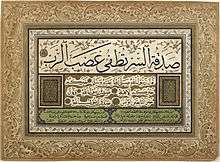

Naskh script in an early 16th-century Ottoman manuscript dedicated to Selim I. Diploma of competency in calligraphy, written with thuluth and naskh script.

Diploma of competency in calligraphy, written with thuluth and naskh script._(6009410911).jpg) Thuluth script tile in Samarkand.

Thuluth script tile in Samarkand. Calligraphy of Ali decorating Hagia Sophia.

Calligraphy of Ali decorating Hagia Sophia.

Regional varieties

Ta'liq script in an Ottoman manuscript.

Ta'liq script in an Ottoman manuscript. Nasta'liq Script.

Nasta'liq Script. Proportions of the nasta'liq script.

Proportions of the nasta'liq script. Sini script in an 11th-century Qur'an.

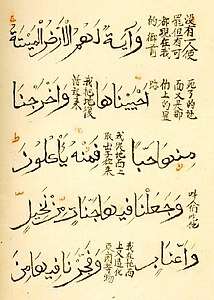

Sini script in an 11th-century Qur'an. Chinese Qur'an written in Sini with Chinese translation.

Chinese Qur'an written in Sini with Chinese translation. The Word "Allah" written in the Form of Pigeon in Chota Imambara

The Word "Allah" written in the Form of Pigeon in Chota Imambara

Modern examples

- Bismallah calligraphy.

Muhammad calligraphy

Muhammad calligraphy Bismallah calligraphy.

Bismallah calligraphy. An example of zoomorphic calligraphy.

An example of zoomorphic calligraphy. flag of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan 2001.

flag of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan 2001. Animation showing the calligraphic composition of the Al Jazeera logo.

Animation showing the calligraphic composition of the Al Jazeera logo. The Emirates logo is written in traditional Arabic calligraphy.

The Emirates logo is written in traditional Arabic calligraphy. The instruments and work of a student calligrapher.

The instruments and work of a student calligrapher. Islamic calligraphy performed by a Malay Muslim in Malaysia. Calligrapher is making a rough draft.

Islamic calligraphy performed by a Malay Muslim in Malaysia. Calligrapher is making a rough draft.

List of calligraphers

Some classical calligraphers:

- Medieval

- Ibn Muqla (d. 939/940)

- Ibn al-Bawwab (d. 1022)

- Fakhr-un-Nisa (12th century)

- Yaqut al-Musta'simi (d. 1298)

- Mir Ali Tabrizi (d. 14th–15th century)

- Ottoman era

- Shaykh Hamdullah (1436–1520)

- Hamid Aytaç (1891-1982)

- Seyyid Kasim Gubari (d. 1624)

- Hâfiz Osman (1642–1698)

- Mustafa Râkim (1757–1826)

- Mehmed Shevki Efendi (1829–1887)

- Contemporary

- Ali Adjalli (b. 1939), Iran

- Wijdan Ali (b. 1939), Jordan

- Hashem Muhammad al-Baghdadi in Iraq

- Hamid Aytaç

- Mohammad Hosni Syria

- Shakkir Hassan Al Sa'id (1925-2004) in Iraq

- Madiha Omar Iraqi-American

- Sadequain Naqqash (1930-1987), Pakistan

- Ibrahim el-Salahi (b. 1930), Sudan

- Mahmoud Taha (b. 1942), Jordan

- Charles Hossein Zenderoudi (b. 1937), Iran

- Abdulraouf Baydoun (b. 1970), Syria

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Blair, Sheila S.; Bloom, Jonathan M. (1995). The art and architecture of Islam : 1250–1800 (Reprinted with corrections ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06465-9.

- 1 2 3 Chapman, Caroline (2012). Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, ISBN 978-979-099-631-1

- 1 2 3 Julia Kaestle (10 July 2010). "Arabic calligraphy as a typographic exercise".

- ↑ Irvin Cemil Schick, “The Content of Form: Islamic Calligraphy Between Text and Representation,” in Sign and Design, ed. B. Bedos-Rezak and J. Hamburger (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2016), 169–190.

- ↑ Sunan Abi Dawud, Sunnah 4699.

- ↑ "History of the Arabic Type Evolution from 1930 till Present".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kvernen, Elizabeth (2009). "An Introduction of Arabic, Ottoman, and Persian Calligraphy: Style". Calligraphy Qalam.

- ↑ "Kūfic script". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Jonathan M. Bloom; Sheila Blair (2009). The Grove encyclopedia of Islamic art and architecture. Oxford University Press. pp. 101, 131, 246. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ↑ Mack, Rosamond E. Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300–1600, University of California Press, 2001 ISBN 0-520-22131-1

- ↑ Mamoun Sakkal (1993). "The Art of Arabic Calligraphy, a brief history".

- 1 2 "Library of Congress, Selections of Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman Calligraphy: Qur'anic Fragments". International.loc.gov. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ↑ Kampman, Frerik (2011). Arabic Typography; its past and its future

- ↑ Mansour, Nassar (2011). Sacred Script: Muhaqqaq in Islamic Calligraphy. New York: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84885-439-0

- ↑ "Ta'liq Script". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ "Diwani script". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ "Gallery", Haji Noor Deen.

- ↑ Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294

- ↑ Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, Online: https://mjmes.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/article-5/;Tuohy, A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette UK, 2015, p. 56

- ↑ Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, pp 1294-95

- ↑ Mir-Kasimov, O., Words of Power: Hurufi Teachings Between Shi'ism and Sufism in Medieval Islam, I.B. Tauris and the Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2015

- ↑ Lindgren, A. and Ross, S., The Modernist World, Routledge, 2015, p. 495; Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, Online: https://mjmes.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/article-5/; Tuohy, A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette UK, 2015, p. 56

- ↑ Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294

- ↑ Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294

- ↑ Dadi. I., "Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism in a Comparative Perspective," South Atlantic Quarterly, 109 (3), 2010 pp 555-576, DOI:https://doi.org/10.121500382876-2010-006; Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294

- ↑ Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1298-1299

- ↑ Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, Online: https://mjmes.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/article-5/;Tuohy, A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette UK, 2015, p. 56; Dadi. I., "Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism in a Comparative Perspective," South Atlantic Quarterly, 109 (3), 2010 pp 555-576, DOI:https://doi.org/10.121500382876-2010-006

- ↑ Talhami, Ghada Hashem (2013). Historical Dictionary of Women in the Middle East and North Africa. p. 24. ISBN 081086858X. ; Hashem Talham, G., Historical Dictionary of Women in the Middle East and North Africa, Rowman & Littlefield, 2013 p. 24; Ramadan, K.D., Peripheral Insider: Perspectives on Contemporary Internationalism in Visual Culture, Museum Tusculanum Press, 2007, p. 49; Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, Online: https://mjmes.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/article-5/

- ↑ Asfour. M., "A Window on Contemporary Arab Art," NABAD Art Gallery, Online: http://www.nabadartgallery.com/

- ↑ "Shaker Hassan Al Said," Darat al Funum, Online: www.daratalfunun.org/main/activit/curentl/anniv/exhib3.html; Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294

- ↑ Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294

- ↑ Grebenstein, M., Calligraphy Bible: A Complete Guide to More Than 100 Essential Projects and Techniques, 2012, p. 5

- ↑ Alabaster, Olivia. "I like to write Beirut as it’s the city that gave us everything", The Daily Star, Beirut, 09 February 2013

- ↑ Vandalog (3 May 2011). "A1one in Tehran IRAN". Vandalog. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

Sources

- Wolfgang Kosack: Islamische Schriftkunst des Kufischen. Geometrisches Kufi in 593 Schriftbeispielen. Deutsch – Kufi – Arabisch. Christoph Brunner, Basel 2014, ISBN 978-3-906206-10-3.

-Jerusalem-Temple_Mount-Dome_of_the_Rock_(SE_exposure).jpg)