Djong (ship)

Djong (also called jong, jung, or junk) is a type of ancient sailing ship originating from Java that is widely used by Javanese and Malay sailors. Djongs are used mainly as seagoing passenger and cargo vessels. They traveled as far as Ghana or even Brazil in ancient times. The average burthen was 4-500 tons, with a range of 85-700 tons. In the Majapahit era these vessels were used as warship, but still predominantly as transport vessels.[1]

Etymology

The name "jung" comes from the Chinese word chuan which means boat.[2] However, the change of pronunciation from chuan to jong seems too far away. The closer is "Djong" in Javanese, which means ship.[3] The word jong can be found in a number of ancient Javanese inscriptions dating to the 9th century.[4] It entered Malay language by the 15th century, when a Chinese word list identified it as a Malay word for ship. The Malay Maritime Laws, first drawn up in the late 15th century, uses junk frequently as the word for freight ships.[5] European writings from 1345 through 1601 use a variety of related terms, including jonque (French), ioncque (Italian), iuncque (Spanish), and ionco (Dutch).[6]

Nusantaran sailor

The Nusantaran archipelago is also known as the producer of large junks (Javanese: Djong Jawa / Jong Jawa). A Portuguese account described how the Javanese people already had advanced seafaring skills when they arrived:[7]

(The Javanese) are all men very experienced in the art of navigation, to the point that they claim to be the most ancient of all, although many others give this honor to the Chinese, and affirm that this art was handed on from them to the Javanese. But it is certain that they formerly navigated to the Cape of Good Hope and were in communication with the east coast of the island of San Laurenzo (Madagascar), where there are many brown and Javanized natives who say they are descended from them.

— Diogo de Couto, Decada Quarta da Asia

When the Portuguese captured Malacca, they recovered a chart from a Javanese pilot, Albuquerque said:

"...a large map of a Javanese pilot, containing the Cape of Good Hope, Portugal and the land of Brazil, the Red Sea and the Sea of Persia, the Clove Islands, the navigation of the Chinese and the Gom, with their rhumbs and direct routes followed by the ships, and the hinterland, and how the kingdoms border on each other. It seems to me. Sir, that this was the best thing I have ever seen, and Your Highness will be very pleased to see it; it had the names in Javanese writing, but I had with me a Javanese who could read and write. I send this piece to Your Highness, which Francisco Rodrigues traced from the other, in which Your Highness can truly see where the Chinese and Gores come from, and the course your ships must take to the Clove Islands, and where the gold mines lie, and the islands of Java and Banda, of actions of the period, than any of his contemporaries; and it appears highly probable, that what he has related is substantially true: but there is also reason to believe that he composed his work from recollection, after his return to Europe, and he may not have been scrupulous in supplying from a fertile imagination the unavoidable failures of a memory, however richly stored."

— Letter of Albuquerque to King Manuel I of Portugal, April 1512.[8]

For seafaring, the Malay (Nusantaran) people independently invented junk sails, made from woven mats reinforced with bamboo, at least several hundred years before 1 BC. By the time of the Han dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD) the Chinese were using such sails, having learned it from Malay sailors visiting their Southern coast. Beside this type of sail, they also made balance lugsails (tanja sails). The invention of these types of sail made sailing around the western coast of Africa possible, because of their ability to sail against the wind.[9]

Description

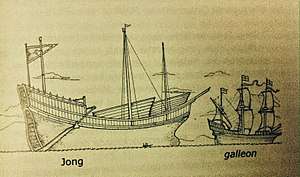

Duarte Barosa reported that the ships from Java, which have four masts, are very different from Portuguese ships. A Javanese ship is made of very thick wood, and as it gets old, the Javanese fix it with new boards. The rope and the sail is made with osier.[10] The Javanese junks were made using jaty/jati wood (teak) at the time of his report (1512), at that time Chinese junks were still using softwood as their main material.[11] The Javanese ship's hull is formed by joining planks to the keel and then to each other by wooden dowels, without using either a frame (except for subsequent reinforcement), nor any iron bolts or nails. The vessel was similarly pointed at both ends, and carried two oar-like rudders and lateen-rigged sails.[note 1] It differed markedly from the Chinese vessel, which had its hull fastened by strakes and iron nails to a frame and to structurally essential bulkheads which divided the cargo space. The Chinese vessel had a single rudder on a transom stern, and (except in Fujian and Guangdong) they had flat bottoms without keels.[5] Historical engravings also depict usage of bowsprits and bowsprit sails, and the appearance of stemposts and sternposts.[12]

The size and special requirements of the djong demanded access to expertise and materials not available everywhere. Consequently, the djong was mainly constructed in two major shipbuilding centres around Java: north coastal Java, especially around Rembang-Demak (along the Muria strait) and Cirebon; and the south coast of Borneo (Banjarmasin) and the adjacent islands. A common feature of these places was their accessibility to forests of teak, as this wood was highly valued because of its resistance to shipworm. Southern Borneo's supply of teak would have come from north Java, whereas Borneo itself would supply ironwood.[12]

History

Greek Astronomer, Claudius Ptolemaeus, ca. AD 100, said in his work Geography that huge ships came from the east of India. This was also confirmed by an anonymous work called Periplus Marae Erythraensis. Both mention a type of ship called kolandiaphonta, which may be a translation of the Chinese word K'un-lun po.[13]

The 3rd century book "Strange Things of the South" (南州異物志) by Wan Chen (萬震) describes ships capable of carrying 700 people together with 260 tons of cargo ("more than 10,000 "斛"). These ships came from K'un-lun, meaning "Southern country" or "Islands below the wind." The ships called K'un-lun po (or K'un-lun bo), could be more than 50 meters in length and had a freeboard of 4-7 meters. Wan Chen explains the ships' design as follows:

The four sails do not face directly forward, but are set obliquely, and so arranged that they can all be fixed in the same direction, to receive the wind and to spill it. Those sails which are behind the most windward one receiving the pressure of the wind, throw it from one to the other, so that they all profit from its force. If it is violent, (the sailors) diminish or augment the surface of the sails according to the conditions. This oblique rig, which permits the sails to receive from one another the breath of the wind, obviates the anxiety attendant upon having high masts. Thus these ships sail without avoiding strong winds and dashing waves, by the aid of which they can make great speed.

— Wan Chen, [14]

A 260 CE book by Kang Tai (康泰) also described these ships as seven-masted vessels called K'un-lun po (Southern country ships) that could travel as far as Syria.[15] The word "po" is derived from the Malay word proa-prauw-perahu, which means large ship. Note that in modern usage, perahu refers to a small boat. Faxian in his return journey to China from India (413-414) embarked a ship carrying 200 passengers and sailors from K'un-lun which towed a smaller boat. A cyclone struck and forced the passengers to move into the smaller boat, leaving them stranded in Ye-po-ti (Yawadwipa - Java).[note 2] After 5 months, the crew and the passengers built a new ship comparable in size to sail back to China.[16]

In I-ch’ieh-ching yin-i, a dictionary compiled by Huei-lin ca. 817 AD, po is mentioned several times:

Ssu-ma Piao, in his commentary on Chuang Tzü, said that large ocean-going ships are called "po”. According to the Kuang Ya, po is an ocean-going ship. It has a draught[note 3] of 60 feet (18 m). It is fast and carries 1000 men as well as merchandise. It is also called k’un-lun-po.[17]

In 1178, the Guangzhou customs officer Zhou Qufei, wrote in Lingwai Daida about the ships of the Southern country:

The ships which sail the southern sea and south of it are like giant houses. When their sails are spread they are like great clouds in the sky. Their rudders are several tens of feet long. A single ship carries several hundred men, and has in the stores a year's supply of grain. Pigs are fed and wine fermented on board. There is no account of dead or living, no going back to the mainland when once the people have set forth upon the cerulean sea. At daybreak, when the gong sounds aboard the ship, the animals can drink their fill, and crew and passengers alike forget all dangers. To those on board everything is hidden and lost in space, mountains, landmarks, and the countries of foreigners. The shipmaster may say "To make such and such a country, with a favourable wind, in so many days, we should sight such and such a mountain, (then) the ship must steer in such and such a direction". But suddenly the wind may fall, and may not be strong enough to allow of the sighting of the mountain on the given day; in such a case, bearings may have to be changed. And the ship (on the other hand) may be carried far beyond (the landmark) and may lose its bearings. A gale may spring up, the ship may be blown hither and thither, it may meet with shoals or be driven upon hidden rocks, then it may be broken to the very roofs (of its deckhouses). A great ship with heavy cargo has nothing to fear from the high seas, but rather in shallow water it will come to grief.[18]

In 1322 friar Odoric of Pordenone reported that the archipelagic vessel of the zunc[um] type carried at least 700 people, either sailors or merchants.[19]

The Majapahit Empire used jongs as its main source of naval power. At its peak, the Majapahit had about 400 large jongs in 5 fleets. Each ship was about 70 metres (230 ft) long, with burthen around 500 tons and could carry 600 men. The ships were armed with 3 meter long cannons, and numerous smaller cetbangs.[20] Prior to the Battle of Bubat in 1357, the Sunda king and the royal family arrived in Majapahit after sailing across the Java Sea by nine-decked hybrid Sino-Southeast Asian junks (Old Javanese: Jong sasanga wagunan ring Tatarnagari tiniru). These hybrid junk incorporated Chinese techniques, such as using iron nails alongside wooden dowels. [21]

Niccolò da Conti, in relating his travels in Asia between 1419 and 1444, describes ships much larger than European ships, capable of reaching 2,000 tons in size, with five sails and as many masts. The lower part is constructed with three planks, to withstand the force of the tempests to which they are much exposed. The ships are built in compartments, so that if one part is punctured, the other portion remaining intact to accomplish the voyage.[22]

Fra Mauro in his map explained that one junk rounded the Cape of Good Hope and traveled far into the Atlantic Ocean, in 1420:

About the year of Our Lord 1420 a ship, what is called an Indian zoncho, on a crossing of the Sea of India towards the "Isle of Men and Women", was diverted beyond the "Cape of Diab" (Shown as the Cape of Good Hope on the map), through the "Green Isles" (lit. "isole uerde", Cabo Verde Islands), out into the "Sea of Darkness" (Atlantic Ocean) on a way west and southwest. Nothing but air and water was seen for 40 days and by their reckoning they ran 2,000 miles and fortune deserted them. When the stress of the weather had subsided they made the return to the said "Cape of Diab" in 70 days and drawing near to the shore to supply their wants the sailors saw the egg of a bird called roc, which egg is as big as an amphora.

— Text from Fra Mauro map, 10-A13, [23]

The Portuguese historian João de Barros (1496–1570) wrote that when a violent storm arose as Albuquerque's fleet entered the vast waters between Sri Lanka and Aceh, a ship commanded by Simão Martinho was sunk, but his entire crew was rescued by Fernão Pires de Andrade and taken aboard his ship. To make up for this loss, the Portuguese captured and commandeered five ships from Gujarat that were sailing between Malacca and Sumatra. The small fleet of Albuquerque engaged an enemy "junk" ship of the Malaccan "Moors" near an island between Lumut and Belawan. According to Barros, they fought against this ship for two days. The enemy crew employed tactics of setting their own ship on fire as a means of burning Albuquerque's ships as they employed ramming techniques and close-range volleys of artillery. Although the ship surrendered, the Portuguese gained such an admiration for the junk and its crew that they nicknamed it O Bravo (The Brave Junk). The Portuguese crew pleaded with Fernão Pires to convince Albuquerque that the crew should be spared and viewed vassals of Portugal who were simply unaware of who they were actually fighting. Albuquerque eventually agreed to this.[24]

Passing by Pacem (Samudera Pasai) the Portuguese came across a Djong—a junk larger and faster than their flagship, the Flor do Mar. At the time, the Portuguese currently had one squadron of 40-43 vessels. The Portuguese ordered it to halt but it promptly opened fire on the fleet, after which the Portuguese quickly followed suit. Reported by Gaspar Correia:[25]

"Because the junco started the attack, the Governor approached him with his entire fleet. The Portuguese ships began firing on the junco, but it had no effect at all. Then the junco sailed away .... The Portuguese ships then fired on the junco masts .... and the sails are falling. Because it's so tall, our people dare not board it, and our shots did not spoil it one bit because the junco has four layers of board. Our largest cannon was only able to penetrate no more than two layers ... Seeing that, the Governor ordered his nau (carrack) to move to the side of junco. This ship is Flor de la Mar, the highest Portuguese ship. And while trying to climb the junco, the rear of the ship could barely reach its bridge. The junco's crew defended themselves so well that the Portuguese ships were forced to sail away from the ship again. (After two days and two nights of fighting) the Governor decides to break the two rudders at the side of the vessel. Only then did the junco surrender."

— Albuquerque

Once aboard, the Portuguese found a member of the royal family of Pacem, whom Albuquerque hoped he could exchange for the Portuguese prisoners.

In January 1513 Paty Onuz (also known as Fatih Yunus or Pati Unus) tried to surprise Malacca with 100 vessels with 5,000 Javanese from Jepara and Palembang. About 30 of those were junks weighing about 350-600 tons (except for Pati Unus' flagship), the rest being smaller boats of pangajava, lancaran, and kelulus types. These vessels carried much Javanese artillery.[note 4] Although defeated, Pati Unus sailed home and beached his warship as a monument of a fight against men he called the bravest in the world, his exploit winning him a few years later the throne of Demak.[26] In a letter to Afonso de Albuquerque, from Cannanore, 22 Feb. 1513, Fernão Pires de Andrade, the Captain of the fleet that routed Pate Unus, says:[11]

"The junk of Pati Unus is the largest seen by men of these parts so far. It carried a thousand fighting men on board, and your Lordship can believe me . . . that it was an amazing thing to see, because the Anunciada near it did not look like a ship at all. We attacked it with bombards, but even the shots of the largest did not pierce it below the water-line, and (the shots of) the esfera (Portuguese large cannon) I had in my ship went in but did not pass through; it had three sheathings, all of which were over a cruzado thick. And it certainly was so monstrous that no man had ever seen the like. It took three years to build, as your Lordship may have heard tell in Malacca concerning this Pati Unus, who made this armada to become king of Malacca."

— Fernao Peres de Andrade, Suma Oriental

The Portuguese remarked that such large, unwieldy ships were weaknesses. The Portuguese succeeded in repelling the attack using smaller but more maneuverable ships. They did not specify the exact size of Pati Unus' junk, only noted that it must have been 4-5 times the size of Flor do Mar (a nau). This would make its size about 144-180 m, with the tonnage between 1600-2000 tons.[20] Other scholars put it as low as 1000 tons, which indicates a length of 70-90 m.[4]

Giovanni da Empoli (a Florentine merchant) said that in the land of Java, a junk is no different in its strength than a castle, because it had three and four boards, one above the other, which cannot be harmed with artillery. They sail with their women, children, and family, and everyone has a room to themselves.[27]

Tome Pires in 1515 wrote that the authorities of Canton (Guangzhou) made a law that obliged foreign ships to anchor at an island off-shore. He said that the Chinese made this law about banning ships from Canton for fear of the Javanese and Malays, for it was believed that one of their junks would rout 20 Chinese junks. China had more than a thousand junks, but one ship of 400 tons could depopulate Canton, and this depopulation would bring great loss to China. The Chinese feared that the city would be taken from them, because Canton was one of China's wealthiest city.[11]

In 1574, queen Kalinyamat of Jepara attacked the Portuguese Malacca with 300 vessels, which included 80 jong of 400 tons burthen and 220 kelulus. The attacking force retreated after 30 jongs were set on fire by the Portuguese and their supplies dwindled. It is also to be noted that by this time European ships has increased in size to 400-500 tons galleon.[28]

Decline

Production of djongs ended in the 1700s, perhaps because of the decision of Amangkurat I of Mataram Sultanate to destroy ships on coastal cities and close ports to prevent them from rebelling. The disappearance of Muria strait denied the shipbuilders around Rembang-Demak access to open water. By 1677, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) reported that the Javanese no longer owned large ships and shipyards.[29] When the VOC gained a foothold in Java, they prohibited the locals from building vessels more than 50 tons in tonnage and assigned European supervisors to shipyards.[21]

Replica

- A small sized replica is moored along the Marine March of Resorts World Sentosa, Singapore.[30]

In popular culture

- Jong is an Indonesian unique unit in Sid Meier's Civilization VI video game. However, the model used in-game closely resembling Borobudur ship than actual jong.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Tanja sails, in the early European reports, are called lateen sail. Also, this type of sail may looked like triangular sail when sighted from afar.

- ↑ Some scholars believe this place is actually Kalimantan.

- ↑ Might be a mistranslation.

- ↑ Most likely refers to regional swivel gun like cetbang or rentaka and medium cannon of lela type.

References

- ↑ Reid, Anthony (2012). Anthony Reid and the Study of the Southeast Asian Past. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9814311960.

- ↑ Collins Compact Dictionary. HarperCollins. 2002. p. 483. ISBN 0-00-710984-9.

- ↑ Junk, Online Etymology Dictionary

- 1 2 Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1993). "Trading Ships of the South China Sea. Shipbuilding Techniques and Their Role in the History of the Development of Asian Trade Networks". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient: 253–280.

- 1 2 Reid, Anthony (2000). Charting the Shape of Early Modern Southeast Asia. Silkworm Books. ISBN 9747551063.

- ↑ "JONQUE : Etymologie de JONQUE". www.cnrtl.fr (in French). Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ↑ de Couto, Diogo (1602). Decada Quarta da Asia. Portugal: Em Lisboa : Impresso por Pedro Crasbeeck.

- ↑ Cartas de Afonso de Albuquerque, Volume 1, p. 64, April 1, 1512

- ↑ Shaffer, Lynda Norene (1996). Maritime Southeast Asia to 1500. M.E. Sharpe. Quoting Johnstone 1980: 191-192

- ↑ Michel Munoz, Paul (2008). Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Continental Sales. pp. 396–397. ISBN 9814610119.

- 1 2 3 Pires, Tome. Suma Oriental. London: The Hakluyt Society. ISBN 9784000085052.

- 1 2 Manguin, P.Y. (1980). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Dick-Read, Robert (2005). The Phantom Voyagers: Evidence of Indonesian Settlement in Africa in Ancient Times. Thurlton.

- ↑ "Strange Things of the South", Wan Chen, from Robert Temple

- ↑ Reid, Anthony (1988). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ↑ Micheal Jacq-Hergoualc'h (2002). The Malay Peninsula: Crossroads of the Maritime Silk-Road (100 BC-1300 AD). BRILL. pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Christie, Anthony (1957). An Obscure passage from the Periplus: Kolandiaphonta ta Megista. London: University of London.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 464.

- ↑ Yule, Sir Henry (1866). Cathay and the way thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China vol. 1. London: The Hakluyt Society.

- 1 2 Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (2011). Majapahit Kerajaan Maritim. Suluh Nuswantara Bakti. ISBN 9786029346008.

- 1 2 Lombard, Denys (1990). The Javanese Crossroads. Essay of Global History. ISBN 2713209498.

- ↑ R. H. Major, ed. (1857), "The travels of Niccolo Conti", India in the Fifteenth Century, Hakluyt Society, p. 27 Discussed in Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, p. 452

- ↑ Text from Fra Mauro map, 10-A13, original Italian: "Circa hi ani del Signor 1420 una naue ouer çoncho de india discorse per una trauersa per el mar de india a la uia de le isole de hi homeni e de le done de fuora dal cauo de diab e tra le isole uerde e le oscuritade a la uia de ponente e de garbin per 40 çornade, non trouando mai altro che aiere e aqua, e per suo arbitrio iscorse 2000 mia e declinata la fortuna i fece suo retorno in çorni 70 fina al sopradito cauo de diab. E acostandose la naue a le riue per suo bisogno, i marinari uedeno uno ouo de uno oselo nominato chrocho, el qual ouo era de la grandeça de una bota d'anfora."

- ↑ Dion, Mark. "Sumatra through Portuguese Eyes: Excerpts from João de Barros' 'Decadas da Asia',". Indonesia (Volume 9, 1970): 128–162.

- ↑ Correia, Gaspar (1602). Lendas da Índia vol. 2. p. 219.

- ↑ Winstedt. A History of Malay. p. 70.

- ↑ da Empoli, Giovanni (2010). Lettera di Giovanni da Empoli. California: Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

- ↑ Sumatra, 431. William Marsden, Cambridge University Press (2012). The History of Sumatra: Containing an Account of the Government, Laws, Customs, and Manners of the Native Inhabitants.

- ↑ Kurniawan, Rendra F. (2009). Jung Jawa. Babel Publishing. ISBN 978-979-25-3953-0.

- ↑ "I ship it! Historic Ship Harbour at RWS". S.E.A. Aquarium at Resorts World Sentosa. 2014-06-04. Retrieved 2018-08-14.