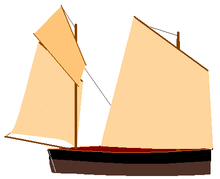

Lug sail

The lug sail, or lugsail, is a fore-and-aft, four-cornered sail that is suspended from a spar, called a yard. When raised the sail area overlaps the mast. For "standing lug" rigs, the sail remains on the same side of the mast on both the port and starboard tacks. For "dipping lug" rigs, the sail is lowered partially to be brought around to the leeward side of the mast in order to optimize the efficiency of the sail on both tacks.

The lug sail is evolved from the square sail to improve how close the vessel can sail into the wind. Square sails, on the other hand, are symmetrically mounted in front of the mast and are manually angled to catch the wind on opposite tacks. Since it is difficult to orient square sails fore and aft or to tension their leading edges (luffs), they are not as efficient upwind, compared with lug sails.[1] The lug rig differs from the gaff rig, also fore-and-aft, whose sail is instead attached at the luff to the mast and is suspended from a spar (gaff), which is attached to, and raised at an angle from, the mast.[2]

Origin

The lug sail was one of the earliest fore-and-aft rigs. Campbell cites the lug sail as an intermediate step between the square sail and the lateen sail, developed for use on the Indian Ocean.[1] McGrail notes the presence of temple carvings of vessels with lug sails, dating from the eighth-ninth century in Borobudur, Indonesia.[3] Block reports a sixth-century depiction of a vessel with lug sails in the Ajanta Caves of India.[2] Salamon suggests that the lateen may have evolved back towards a balanced lug rig, as used in the Adriatic.[4]

The origin of its name is uncertain. According to Skeat, the name of the sail may derive from the ease with which it may be raised or "lugged" or it may derive from the vessel type, " lugger", on which the sail is used, which name may come from Dutch, logger meaning "slow ship", and East Friesian, log meaning "slow".[5]

Types

Lug sails are divided into three types: standing lug, balanced lug and dipping lug.[2]

- Standing lug: The sail and yard remain on one side of the mast and the tack of the sail is set close to the mast. When the wind blows onto the side of the mast where the sail is mounted, it deforms the sail over the mast. The standing lug differs from the balanced rig. On a standing lug the yard extends past the mast, but the foot of the sail, which may be loose-footed, does not.[6]

- Balanced lug: The sail has both a yard and a boom, which both extend past the mast and remain on the same side of the mast on either tack. A junk rig (a fully battened sail that crosses the mast at the head and foot) is similar to a balanced lug.[6]

- Dipping lug: This is a loose-footed sail whose yard is designed to be lowered, "dipped", sufficiently to bring the sail around to the leeward side of the mast when tacking to allow the sail to achieve a shape that is not influenced by the mast pressing into it. This allows a more efficient air flow and reduces wear of the canvas. Because of the complexity of dipping, the yard is smaller than on the standing lug.[6]

Lug sail design also varies with the angle that the yard crosses the mast; a standing lug with the gaff parallel to the mast is called a "gunter" rig.[2]

Procedures for tacking by dipping

Whereas a standing lug may be tacked conventionally by moving the sail across the vessel, as the wind crosses the bow, a dipping lug must be brought around to the leeward side by a multi-step procedure:[7]

- Hauling in the sheets to get the sail over the boat.

- Lowering the halyard so that the peak of the sail can be reached, yet the yard is free of interfering with the rest of the boat.

- Gathering the after part of the sail and bringing it around forward of the mast.

- Bringing the peak down and passing it under the luff of the sail to the new leeward side.

- Bringing the halyard to windward aft of the mast.

- Shackling on the sheets and bringing the sail aft.

- Rehoisting the sail and sheeting in.

This procedure is also necessary for gybing a dipping lug. Reportedly, this action can be completed expeditiously on a larger boat with four hands. On smaller boats, the sail is simply lowered and the mast unstepped to allow the sail to be moved beneath it to the other side and the mast to be re-stepped and the sail raised.[7]

There are other ways to tack or gybe a lugsail. Some methods use a downhaul to the forward end of the spar so that a sharp downward tug on the line will pull dip the forward end around the aft side of the mast. Generally the procedure, which may be feasible only on smaller sails, is to:

- lower the yard sufficiently to allow the dip

- swap the sail tack and tug the yard downhaul

- move the halyard to windward

- rehoist and sheet in.

The Beer Luggers, which normally have the tack of the sail set to a small bowsprit where untacking it is difficult, will have the lazy sheet forward of the luff of the sail and will use it haul the whole sail around its own luff, leaving the old working but now lazy sheet again forwards around the luff of the sail.

On larger luggers, like the Fifie, large dipping lug sails were possible only with the introduction of steam-powered capstans to facilitate with dipping.[8]

Extent of use

Block reports that the rig was widely used in Europe from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries for small fishing vessels and other coasters because of their good performance to windward. This popularity extended to smugglers and privateers and the French chasse-marée fishing boats.[2]

Currently, lug rigs are used on certain small sailing craft, like the International Twelve Foot Dinghy, a dinghy,[9] and the SCAMP, a pocket cruiser.[10]

See also

- Lugger

- Junk rig, also known as the Chinese lugsail

- Tanja sail, a type of sail from Nusantaran archipelago

References

- 1 2 Campbell, I.C. (1995). "The Lateen Sail in World History" (PDF). Journal of World History. University of Hawai'i Press (Spring): 23. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Block, Leo (2003). To Harness the Wind: A Short History of the Development of Sails. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. p. 164. ISBN 9781557502094.

- ↑ McGrail, Seán (2004), Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to Medieval Times, Oxford University Press, p. 480, ISBN 9780199271863

- ↑ Salamon, Velimir (May 2011). "The Croatian Brazzera" (PDF). European Maritime Heritage Newsletter (27): 4–6. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ↑ Skeat, Walter W. (2013). An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Dover language guides (Reprint ed.). Courier Corporation. p. 832. ISBN 9780486317656.

- 1 2 3 Barnes, Roger (2014-01-02). The Dinghy Cruising Companion: Tales and Advice from Sailing a Small Open Boat. A&C Black. ISBN 9781408180280.

- 1 2 Winn, William (1891). The Boating Man's Vade-mecum. London: Swan Sonnenschein. p. 336.

- ↑ March, Edgar J. (1953). Sailing Drifter. London: Percival Marshall & Co.

- ↑ Bird, Vanessa (2012). Classic Classes. A. & C. Black. p. 160. ISBN 9781408158890.

- ↑ James McCoy, "SCAMP: A New Genre of Sailboat", Harbors Magazine, Winter 2013

External links

| Look up lugsail in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "Lug Rigs for Small Sailboats" by John C. Harris