Columbus Circle

Coordinates: 40°46′05″N 73°58′55″W / 40.76806°N 73.98194°W

Columbus Circle is a traffic circle and heavily trafficked intersection in the New York City borough of Manhattan, located at the intersection of Eighth Avenue, Broadway, Central Park South (West 59th Street), and Central Park West, at the southwest corner of Central Park. The circle is the point from which official highway distances from New York City are measured, as well as the center of the 25 miles (40 km) restricted-travel area for C-2 visa holders.

The circle is named after the monument of Christopher Columbus in the center. The name is also used for the neighborhood a few blocks around the circle in each direction. To the south of the circle lies Hell's Kitchen, also known as "Clinton", and the Theater District, and to the north is the Upper West Side.

Monument

The 76-foot (23 m) Columbus Column monument at the center of the circle, created by Italian sculptor Gaetano Russo,[1] consists of a 14-foot (4.3 m) marble statue of Columbus atop a 27.5-foot (8.4 m) granite rostral column[2] on a four-stepped granite pedestal.[3] The column is decorated with bronze reliefs representing Columbus' ships: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María, although actually they are Roman galleys instead of caravels. Its pedestal features an angel holding a globe.[1]

History

The monument was one of three planned as part of the city's 1892 commemoration of the 400th anniversary of Columbus' landing in the Americas.[3] Originally, the monument was planned to be located in Bowling Green or somewhere else in lower Manhattan. By the time Russo's plan was decided upon in 1890, a commission of Italian businessmen from around the United States had contributed $12,000 of the $20,000 needed to build the statue (equivalent to $327,000 of the $545,000 cost in modern dollars).[4] The statue was constructed with funds raised by Il Progresso, a New York City-based Italian-language newspaper.[1]

Russo created parts of the Columbus Column in his Rome studio and in other workshops in Italy;[3] the bronze elements were cast in the Nelli Foundry.[5] The completed column was shipped to the United States in September 1892, to be placed within the "circle at Fifty-ninth Street and Eighth Avenue".[6] Once the statue arrived in Manhattan, it was quickly transported to the circle.[2] The monument was officially unveiled with a ceremony on October 13, 1892, as part of the 400th anniversary celebrations.[7][8][9]:287

During the construction of the IND Eighth Avenue Line (A, B, C, and D trains) underneath the circle in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Columbus statue was shored up with temporary supports.[10] Even so, the statue was shifted two inches north from its original position, and the top of the statue tilted 1.5 inches (3.8 cm). As a result, the statue was repaired and cleaned in 1934.[11] The monument received some retouching in 1992 to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Columbus's voyage, and in turn, the monument's own 100th anniversary.[9]:288 It was also rededicated that year.[12]

Amid the 2017 monument controversies in the United States, an issue arose over the statue due to criticism of Columbus's alleged mistreatment of the native people on Hispaniola. In August of that year, there had been a far-right rally Charlottesville, Virginia, that resulted in a death and several injuries. Following that rally, Mayor Bill de Blasio commissioned a "90-day review" of possibly "hateful" monuments across the city to determine if any of them, including the Columbus Column, warranted either removal or recontextualization (e.g. by explanatory plaques).[13][14] Although calls to remove the monument were supported by those criticizing Columbus's actions, the proposed removal was opposed by some sectors of the city's Italian American community and Columbus Day Parade organizers.[15][16] Due to two incidents of vandalism in September 2017, full-time security measures were put around the column ahead of the year's parade.[17]

On September 20, 2018, in an unanimous decision, the New York State Board of Historic Preservation quietly voted to place the monument on the state and federal historical registers due to its significance.[18]

Circle

The traffic circle, located at Eighth Avenue/Central Park West, Broadway, and 59th Street/Central Park South, was designed as part of Frederick Law Olmsted's 1857 vision for Central Park, which included a rotary on the southwest corner of the park. It abuts the Merchant's Gate, one of the park's eighteen major gates. Similar plazas were planned at the southeast corner of the park (now Grand Army Plaza), the northeast corner (Duke Ellington Circle), and the northwest corner (Frederick Douglass Circle).[19] Clearing of the land area for the circle started in 1868.[20][21]:6 The actual circle was approved two years later.[21]:6

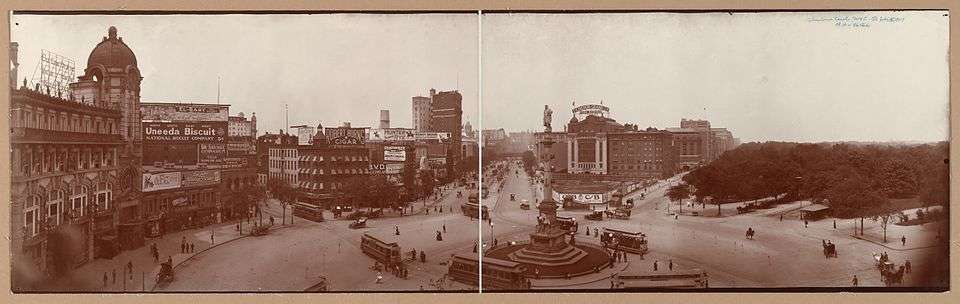

Columbus Circle was originally known generically as "The Circle".[20][19] An 1871 account of the park referred to the roundabout as a "grand circle".[22] After the 1892 installation of the Columbus Column in the circle's center, it became known as "Columbus Circle",[9]:287[23]:124 although its other names were also used through the 1900s.[24]

Modifications

Subway construction

By 1901, construction on the first subway line of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (now the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line, used by the 1, 2, and 3 trains) required the excavation of the circle, and the column and streetcar tracks through the area were put on temporary wooden stilts. As part of the subway line's construction, the 59th Street–Columbus Circle station was built underneath the circle.[25][9]:288 During construction, traffic in the circle was so dangerous that the Municipal Art Society proposed redesigning the roundabout.[24][26] By February 1904, the station underneath was largely complete,[27] and service on the subway line began on October 27, 1904. The station only served local trains; express trains bypassed the station.[28]:162–191[29] The platforms of the IRT subway station were lengthened in 1957–1959, requiring further excavations around Columbus Circle.[30]

An additional subway line—the Independent Subway System (IND)'s Eighth Avenue Line, serving the present-day A, B, C, and D trains—was built starting in 1925. At Columbus Circle, workers had to be careful to not disrupt the existing IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line or Columbus Circle overhead.[31] The Columbus monument was shored up during construction, and obstructions to traffic were minimized.[10] The line, which opened in 1932, contains a 4-track, 3-platform express station at 59th Street–Columbus Circle, underneath the original IRT station.[32] The IND station were designed as a single transit hub under Columbus Circle.[33]

Eno's traffic plan

In November 1904, due to the high speeds of cars passing through the circle, the New York City Police Department added tightly spaced electric lights on the inner side of the circle, surrounding the column.[34]

The current circle was redesigned in 1905 by William Phelps Eno, a businessman who pioneered many early innovations in road safety and traffic control.[35][36] In a 1920 book, Eno writes that prior to the implementation of his plan, traffic went around the circle in both directions, causing accidents almost daily. The 1905 plan, which he regarded as temporary, created a counterclockwise traffic pattern with a "safety zone" in the center of the circle for cars stopping; however, the circle was too narrow for the normal flow of traffic. Eno also wrote of a permanent plan, with the safety zones on the outside as well as clearly delineated pedestrian crossings.[37] The redesign marked the first true one-way traffic circle to be constructed anywhere, implementing the ideas of Eugène Hénard.[36][38] In this second scheme, the public space within the circle, around the monument, was almost as small as the monument's base.[39]

The rotary traffic plan was not successful. A New York Times article in June 1929 stated that the "Christopher Columbus [monument] is safe and serene, but he's the only thing in the Circle that is."[40] At the time, there were eight entrance and exit points to Columbus Circle: two each from 59th Street/Central Park South, to the west and east; Broadway, to the northwest and southeast; Eighth Avenue/Central Park West, to the south and north; and within Central Park to the northeast.[lower-alpha 1] Moreover, streetcars on the former three streets did not go counterclockwise around the rotary, but rather, both tracks of all three streetcar routes went around one side of the monument, creating frequent conflicts between streetcars and automobiles using the rotary in opposite directions. The police officers patrolling the circle had to manage the 58,000 cars that entered Columbus Circle every 12 hours.[40] As part of a plan to reorganize traffic in the "Columbus-Central Park Zone", Eno's circular-traffic plan was abolished in November 1929, and traffic was allowed to go around the circle in both directions.[39][41] Central Park West, a one-way street that formerly carried southbound traffic into the circle, was now one-way northbound.[41] The bidirectional entrance roads into Central Park, which fed into northbound and eastbound West Drive, were both changed to one-way streets because West Drive had been changed from bidirectional to one-way southbound and eastbound.[41][42] Traffic going straight through Columbus Circle was forced to go around the left side of the monument, while any traffic making turns from the circle had to go counterclockwise around the rotary using the right side.[41]

Mid-20th century configurations

The bidirectional traffic pattern through Columbus Circle failed to eliminate congestion. In 1941, engineers with the New York City Parks Department and the Manhattan Borough President's office formed a tentative agreement to redesign Columbus Circle yet again. "Local" and "express" lanes would segregate north-south traffic passing within the circle. Local north-south traffic and all east-west traffic would go around the circle's perimeter in a counterclockwise direction, along a 45-foot-long (14 m) roadway.[43][44] Through north-south traffic on Broadway, Eighth Avenue, and Central Park West would use two 71-foot-wide (22 m) divided roadways with 5-foot-wide (1.5 m) landscaped medians, running in chords on either side of the Columbus monument. Traffic from southbound Broadway and northbound Eighth Avenue would use the western chord, and northbound Broadway and southbound Central Park West would use the eastern chord.[44] The center of the circle would be refurbished with a tree-lined plaza, and pedestrian traffic from the north and south would be able to pass through the center of the circle. The exit into Columbus Circle from West Drive would be eliminated, and the entrance to West Drive would be relocated.[43][45] In a related development, the 59th Street trolley route's tracks would be removed. This was crucial to the reorganization of the circle, as the trolley had already been discontinued.[43]

The proposed reorganization of Columbus Circle was widely praised by civic groups and city officials.[46] On the other hand, William Phelps Eno advocated for a return to his original 1905 proposal.[47] However, the plan still had some issues, the largest of which was that traffic traveling on Broadway in either direction would be routed onto Eighth Avenue or Central Park West, and vice versa.[43][44]

The reconfiguration of the circle was deferred due to World War II.[48] The trolley routes that ran through Columbus Circle were discontinued in 1946, but the bus routes that replaced the trolley lines took the same convoluted paths through the circle.[48] In June 1949, it was announced that the reconstruction of Columbus Circle would finally begin.[44] Work on removing the abandoned trolley tracks commenced in August.[49] In conjunction with Columbus Circle's rehabilitation, the New York City Department of Transportation designed a variable traffic light system for the circle. The project was originally set to be complete by November 1949 at a cost of $100,000.[49] However, delays arose due to the need to maintain traffic flows through the circle during construction.[48] The project was ultimately completed that December.[50]

The entirety of Eighth Avenue south of Columbus Circle was converted to northbound-only traffic in 1950.[51] In 1956, in preparation for the opening of the New York Coliseum on Columbus Circle's west side, traffic on Central Park West and Broadway was rearranged. Central Park West was made northbound-only for a short segment north of the circle, and two blocks of Broadway south of the circle were converted to southbound-only. A new northbound roadway was cut through the southern tip of the center traffic island that contained the statue, from Eighth Avenue to the eastern chord. At the same time, the eastern chord was converted to northbound-only.[52]

1990s and 2000s renovation

By the late 20th century, it was regarded as one of the most inhospitable of the city's major intersections, as the interior circle was being used for motorcycle parking, and the circle as a whole was hard for pedestrians to cross. In 1979, noted architecture critic Paul Goldberger said that the intersection was "a chaotic jumble of streets that can be crossed in about 50 different ways—all of them wrong."[39]

In 1987, the city awarded a $20 million contract to Olin Partnership and Vollmer Associates to create a new design for the circle.[39] The circle was refurbished in 1991–1992 as part of the 500th-anniversary celebration of Columbus's arrival in the Americas.[53][9]:288 In 1998, as a result of the study, the circular-traffic plan was reinstated, with all traffic going around the circle in a counterclockwise direction. The center of the circle was planned for further renovations, with a proposed park 200 feet (61 m) across.[54]

The design for a full renovation of the circle was finalized in 2001.[55] The project started in 2003, and was completed in 2005. It included a new water fountain by Water Entertainment Technologies, who also designed the Fountains of Bellagio; benches made of ipe wood; and plantings encircling the monument.[39][53] The fountain, the main part of the reconstructed circle, contains 99 jets that periodically change in force and speed, with effects ranging between "swollen river, a rushing brook, a driving rain or a gentle shower".[39] The inner circle is about 36,000 square feet (3,300 m2), while the outer circle is around 148,000 square feet (13,700 m2). The redesign was the recipient of the 2006 American Society of Landscape Architects’ General Design Award Of Honor.[55] In 2007 Columbus Circle was awarded the Rudy Bruner Award for Urban Excellence silver medal.[21]

As a geographic center

Columbus Circle is the traditional municipal zero-mile point from which all official distances are measured,[56] although Google Maps uses New York City Hall for this purpose.[57] For decades, Hagstrom sold maps that showed the areas within 25 miles (40 km)[58] or 75 miles (121 km)[59] from Columbus Circle.

The travel area for recipients of a C-2 visa, which is issued for the purpose of immediate and continuous transit to or from the headquarters of the United Nations, is limited to a 25-mile radius of Columbus Circle.[60] The same circle coincidentally defines the city's "film zone" that local unions operate in, a counterpart to Los Angeles' studio zone.[61][62][63][64] The New York City government employee handbook considers a trip beyond a 75-mile radius from Columbus Circle as long-distance travel.[65][66]

Neighborhood

The five streets that radiate outward from Columbus Circle separate the immediate neighborhood around the circle into five distinct portions.[67][68]

West

To the west of the circle is a superblock spanning two streets, bounded by Broadway, 60th Street, Ninth Avenue, 58th Street, and Eighth Avenue.[67] The superblock was formerly two separate blocks.[9]:914 From 1902 to 1954, the Majestic Theatre occupied the more southerly of the two blocks.

Robert Moses demapped 59th Street through the block during the New York Coliseum's construction from 1954 to 1956.[9]:914[69] The construction project, in turn, was the culmination of an effort to remove San Juan Hill, the slum that had been located at the site.[70] Until the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center was built in Hell's Kitchen in the 1980s, the Coliseum was the primary event venue for New York City.[9]:914 By 1985, there were plans to replace the Coliseum,[71] and after a series of delays, the Coliseum was demolished in 2000.[72]

Since 2003, the site has been occupied by Time Warner Center, the world headquarters of the Time Warner corporation.[73]:310[74] The center consists of a pair of 750-foot (230 m) towers 53 stories high.[56][75] The complex also hosts the Shops at Columbus Circle mall, Jazz at Lincoln Center, the New York City studio headquarters of CNN, and the Mandarin Oriental, New York hotel.[9]:1319[56] The mall inside the complex Prestigious restaurants in the center include Landmarc, Per Se and Masa.[76][77] Time Warner also paid for the portion of the new interior circle that directly faces the Time Warner Center.

North

On the north side of Columbus Circle, bounded by Broadway, Central Park West, and 61st Street,[67] is the Trump International Hotel and Tower, with its noted steel globe, which had been an office tower, the headquarters of the Gulf+Western conglomerate, which was stripped to its steel skeleton and reclad in a new facade.[56][78] The Gulf and Western Building, a 44-story building completed in 1969[73]:351 or 1970,[79] filed for bankruptcy in 1991.[79] In 1994, Donald Trump announced his plans to convert the building into a mixed-purpose hotel and condominium units, with hotel rooms below the 14th floor and condominiums above that floor.[80] Renovations started in 1995 after Gulf and Western's lease lapsed and Trump took control of the building.[81] That renovation was complete by 1997.[9]:288[82]

Northeast

On the northeast lies the Merchant's Gate to Central Park, dominated by the USS Maine National Monument. The USS Maine monument was designed by Harold Van Buren Magonigle and sculpted by Attilio Piccirilli, who did the colossal group and figures, and Charles Keck, who was responsible for the "In Memoriam" plaque. An imposing Beaux-Arts edifice of marble and gilded bronze,[83] it was dedicated in 1913 as a memorial to sailors killed aboard the battleship USS Maine,[84] whose mysterious 1898 explosion in Havana harbor precipitated the Spanish–American War.[83]

South

Actors' Equity was founded in 1913 in the old Pabst Grand Circle Hotel,[85] located at 2 Columbus Circle on the southern side of the circle.[86] The building was torn down in 1960 in order to construct a distinctive new International Modernist tower designed by architect Edward Durrell Stone to house the Huntington Hartford Gallery of Modern Art.[86] Vacant since the city's Department of Cultural Affairs departed in 1998,[86] it was listed as one of the World Monuments Fund's "100 most endangered sites" in 2006.[87] After a renovation by architect Brad Cloepfil, the building became the new home for Museum of Arts and Design in 2008.[73]:310[9]:288, 868[88] Its radical transformation was controversial for the failure of the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission to hold hearings on its worthiness for designation.[89][90][91]

Southeast

240 Central Park South, a balconied moderne apartment building across Broadway from the museum, is on the southeast side of the circle. Built in 1941, it is a city-designated landmark with a new addition, a green roof, atop its retail base.[92]:128

3, 4, 5, and 6 Columbus Circle

3, 4, 5, and 6 Columbus Circle are the numbers given to four buildings on the south side of 58th Street. From east to west, the buildings are numbered 5, 3, 4, and 6 Columbus Circle.[68]

5 Columbus Circle (also known by its address, 1790 Broadway),[93] is a 286-foot (87 m), 20-story tower on the southeast corner of Broadway and 58th Street.[94] It was originally built as the headquarters of the United States Rubber Company (U.S. Rubber) in 1912.[73]:308[95] It was part of Broadway's "Automobile Row" during the early 20th century.[96] U.S. Rubber moved to a new headquarters in 1940, and the building was sold several times before being acquired by the West Side Federal Savings and Loan Association. The First Nationwide Savings Bank, which acquired the West Side Federal Savings bank, sold the building in 1985 to 1790 Broadway Associates, its current owners.[95] The lobby contains part of an under-construction flagship store for Nordstrom, which is planned to open in 2019; the 360,000-square-foot (33,000 m2) store itself would be located under three buildings on the block.[97][98]

Between Eighth Avenue and Broadway on the south side of 58th Street is 3 Columbus Circle (also 1775 Broadway), a 310-foot (94 m), 26-story tower.[99] It is occupied by Young & Rubicam, Bank of America, Chase Bank, and Gilder Gagnon Howe & Co.[100] The tower sits atop a 3-story structure called the Colonnade Building.[101][102] The first 3 stories were built in 1923 and the top 23 stories were added as part of a large expansion in 1927–1928.[73]:307 During the expansion, the original building's three-story Ionic supports were kept.[103][101] The new expansion, designed by Shreve & Lamb,[73]:307 hosted General Motors' headquarters from 1927[96][104] to 1968.[104][105] In 1969, Midtown Realty purchased the building's lease, and in 1980, acquired the land. Half of the building was leased by Bankers Trust until the late 1980s,[104] and Newsweek leased a third of the building from 1994[106] until 2006.[107] When the Moinian Group purchased the building in 2000,[101][108] the building assumed its current name;[101][107] a subsequent renovation refurbished the exterior and removed all remnants of the Colonnade Building.[101] A neon sign for CNN was located on the roof of the building from the mid-2000s to 2015.[105] An annex of Nordstrom for menswear is planned for the base of 3 Columbus Circle.[93]

4 Columbus Circle, an eight-story low-rise located at 989 Eighth Avenue at the southwest corner of the intersection with 58th Street, was built in the late 1980s. Swanke Hayden Connell Architects designed the building, which houses the furniture company Steelcase on the upper floors and a Duane Reade and a Starbucks on the ground floor.[109] Cerberus Capital Management bought the building in 2006 for $82.9 million. In 2011, it was sold to German real estate firm GLL Real Estate Partners for $96.5 million.[110]

Directly to the west is 6 Columbus Circle, an 88-room, 12-floor boutique hotel called 6 Columbus.[111] Acquired by the Pomeranc Group in 2007,[112] the hotel was put on sale in December 2015.[113] A 700-foot-tall (210 m) tower is planned for the site.[114]

Transportation

The M5, M7, M10, M20 and M104 buses all serve the circle, with the M5, M7, M20 and M104 providing through service and the southbound M10 terminating near the circle.[115] Under the circle is the 59th Street–Columbus Circle subway station (1, 2, A, B, C, and D trains).[116]

In popular culture

Columbus Circle was featured in the 1976 movie Taxi Driver, where Robert De Niro's character was thwarted in an attempt to assassinate a presidential nominee.[117]

Gallery

- Around Columbus Circle today

The USS Maine National Monument at the Merchant's Gate entrance to Central Park

The USS Maine National Monument at the Merchant's Gate entrance to Central Park Six Columbus, a boutique hotel at 6 Columbus Circle

Six Columbus, a boutique hotel at 6 Columbus Circle

See also

References

Explanatory notes

- ↑ These directions are relative to Manhattan's street grid, which is rotated 29 degrees clockwise from geographic north. So for instance, Broadway really points north and south, while Eighth Avenue/Central Park West points south-southwest and north-northeast respectively.

Citations

- 1 2 3 "New York - Columbus Monument". www.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- 1 2 "ITALY'S GIFT IS HERE" (PDF). The Press. New York, New York. September 5, 1892. p. 2. Retrieved October 13, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 3 "COLUMBUS MEMORIALS.; THREE OF THEM SOON TO BE PRESENTED TO THIS CITY" (PDF). The New York Times. June 13, 1892. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ↑ "FROM ITALIANS TO AMERICA.; THE GREAT STATUE OF COLUMBUS TO ADORN NEW-YORK" (PDF). The New York Times. July 9, 1890. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Central Park Monuments - Columbus Monument". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- ↑ "THE COLUMBUS STATUE.; SAFE IN PORT ON BOARD THE TRANSPORT GARIGLIANO" (PDF). The New York Times. September 6, 1892. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ↑ "THE VOYAGER IN MARBLE; UNVEILING OF THE GREAT COLUMBUS MONUMENT. IMPRESSIVE CEREMONIES VIEWED BY MANY THOUSANDS -- POETIC ADDRESS BY MISS BARSOTTI -- MUSIC AND MILITARY EVOLUTIONS THAT CHARMED THE PEOPLE" (PDF). The New York Times. October 13, 1892. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Columbus is Unveiled by a Little Girl" (PDF). New York Herald. October 13, 1892. p. 6. Retrieved October 13, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010), The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.), New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2

- 1 2 Collins, F.a. (October 10, 1926). "NEW SUBWAY BURROWS UNDER NEW YORK; Old Open Trench Methods No Longer Employed -- Complicated Machinery Carries Huge Task Forward". The New York Times. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Columbus Gleams White As Circle Job Is Finished". The New York Times. November 10, 1934. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ Barron, James (June 21, 1991). "At a Party for Columbus, a Few Uninvited Guests". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Neuman, William (August 30, 2017). "Ordering Review of Statues Puts de Blasio in Tricky Spot". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Helmore, Edward (August 25, 2017). "New York mayor considers Christopher Columbus statue removal". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Zoe (August 23, 2017). "Elected officials call for removal of Christopher Columbus statue near Central Park". Curbed NY. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Columbus Day Parade Organizers Fight To Keep Statue In Columbus Circle". CBS New York. August 30, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Wootson Jr., Cleve R. (October 7, 2017). "Why police have to guard a statue of Christopher Columbus in New York around the clock". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ State designates Columbus Circle monument as landmark Retrieved October 5, 2018

- 1 2 Heckscher, M.H. (2008). Creating Central Park. DE-601)129532134: Metropolitan Museum of Art bulletin. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 50–55. ISBN 978-0-300-13669-2. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- 1 2 Minutes of Proceedings of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park for the Year Ending April 30 ... Wm. C. Bryant & Company, printers. 1869. p. 28. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Silver Medal Winner - Columbus Circle - New York, New York" (PDF). Bruner Foundation. 2008. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ↑ The Metropolis Explained and Illustrated in Familiar Form ... Devlin & Company. 1871. p. 12. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ↑ Feirstein, Sanna (2001), Naming New York: Manhattan Places & How They Got Their Names, New York: New York University Press, ISBN 978-0-8147-2712-6

- 1 2 "IMPROVING COLUMBUS CIRCLE" (PDF). The New York Times. 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ↑ "SCENES ALONG THE ROUTE OF THE TUNNEL; How Work Is Carried on Under the Columbus Column. Circle Station for Rapid Transit Trains Nearing Completion -- Some of the Difficulties Surmounted" (PDF). The New York Times. May 26, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ↑ "EIGHTH AVENUE CIRCLE" (PDF). The New York Times. April 16, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ↑ "By Handcar Through the Subway—End of the Great Engineering Feat Now in Sight" (PDF). The Globe and Commercial Advertiser. February 1, 1904. p. 7. Retrieved October 13, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ Walker, James Blaine (1918). Fifty Years of Rapid Transit — 1864 to 1917. New York, N.Y.: Law Printing. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ↑ "SUBWAY OPENING TO-DAY WITH SIMPLE CEREMONY; Exercises at One o'Clock; Public to be Admitted at Seven. JOHN HAY MAY BE PRESENT Expected to Represent the Federal Government -- President Roosevelt Sends Letter of Regret" (PDF). The New York Times. October 27, 1904. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ↑ Katz, Ralph (May 10, 1958). "IRT TO COMPLETE REPAIRS IN A YEAR; Broadway Express Will Be Modified and Stations Revamped by June, '59 STREET CLEARING IS SET Transit Agency Expects It Will Remove Bottlenecks to Traffic by February". The New York Times. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ Warner, Arthur (November 22, 1931). "THE CITY'S NEW UNDERGROUND PROVINCE; The Eighth Avenue Subway Will Be Not Only a Transit Line but a Centre for the Shopper A NEW UNDERGROUND PROVINCE OF NEW YORK The Eighth Avenue Subway Will Be a Rapid Transit Line With Innovations and Will Provide Centres for the Shoppers". The New York Times. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ↑ "CITY TO OPEN SUBWAY IN 8TH AV. TONIGHT; CROWDS VISIT TUBE". The New York Times. September 9, 1932. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ "PLAN HUGE CENTRE OF SUBWAY TRAFFIC; Transit Lines Will Build Dual Station at Columbus Circle Four Blocks in Length. 16 ENTRANCES PROPOSED Growth of Section From 1905 to 1926 Is Indicated by Rise of 7,167,592 Fares". The New York Times. April 24, 1927. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ "LANE OF ELECTRIC LIGHTS.; Police Plan Measure for Vehicles in the Columbus Circle" (PDF). The New York Times. November 15, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ↑ Henebery, Ann. "The Rules of the Road: Then Versus Now", Eno Center for Transportation, October 6, 2015. Accessed October 9, 2017. "William P. Eno is internationally recognized as an original pioneer of traffic regulation and safety.... He was dubbed the 'Father of Traffic Safety' and many of the traffic-flow innovations that we now take for granted were a result of Eno’s hard work. He is credited with designing Columbus Circle in New York City and the traffic circle surrounding the Arc de Triomphe in Paris."

- 1 2 Petroski, Henry (2016). The Road Taken: The History and Future of America's Infrastructure. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 79. ISBN 9781632863614.

- ↑ Eno, William P. (1920). The Science of Highway Traffic Regulation: 1899-1920. Brentano's. pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Municipal Engineering. Municipal Engineering Company. 1917. p. 111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dunlap, David W. (August 4, 2005). "An Island of Sanctuary in the Traffic Stream". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- 1 2 "COLUMBUS CIRCLE A TRAFFIC MAZE; Intersecting Streets and Car Tracks Make Orderly Movement Impossible--Police Face Problem--Working Out New Plan". The New York Times. June 30, 1929. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "WHALEN INSTALLS NEW TRAFFIC RULES; He Takes Up Post in Columbus Circle to See Effect of Ending 'Rotary' Travel. PRONOUNCES IT PERFECT Central Park Drives Become OneWay and Commissioner HopesPlan Will Cut Accidents. Whalen Takes Up Post. Hopes to Cut Accidents". The New York Times. November 30, 1929. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Whalen Sets Traffic Plans" (PDF). Yonkers Statesman. November 26, 1929. p. 14. Retrieved October 6, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 3 4 "COLUMBUS CIRCLE GETS TRAFFIC PLAN TO END BOTTLENECK". The New York Times. May 9, 1941. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Columbus Circle to Be Rearranged With 5 Roadways and 5 'Islands'; 45-Foot Wide Perimeter Strip and Four Cross Lanes are Planned to Expedite Traffic -- $100,000 Job to Start This Month". The New York Times. June 16, 1949. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ "BOARD TO ACT ON TRAFFIC JAM" (PDF). New York Sun. May 9, 1941. p. 10. Retrieved October 6, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ↑ "MANY BACK PLAN TO BEAUTIFY CIRCLE; City Officials and Civic Units Praise Idea as Benefit to Realty and Traffic LA GUARDIA IS 'IMPRESSED' Elimination of the Soap-Box Orators Is Seen as One Boon in Project". The New York Times. May 10, 1941. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Traffic Expert Advocates Change in Proposal at Columbus Circle". The New York Times. June 8, 1941. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Ingraham, Joseph C. (November 6, 1949). "COLUMBUS CIRCLE TRAFFIC PUZZLE IS REDRAWN". The New York Times. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- 1 2 "Columbus Circle's Traffic Puzzle To Be Simplified by New Design". The New York Times. August 15, 1949. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Traffic Is Faster, Smoother in Test Of Columbus Circle's Rotary Plan; COLUMBUS CIRCLE: THE OLD AND NEW LOOK TRAFFIC IS SPEEDED BY ROTARY LAYOUT". The New York Times. December 6, 1949. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ Ingraham, Joseph C. (December 30, 1950). "More One-Way Avenues Set As City Speeds Defense Plan; MANHATTAN'S ONE-WAY THOROUGHFARES". The New York Times. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ Ingraham, Joseph C. (1956-02-20). "Columbus Circle Traffic Will Shift; Changes Will Include New Road to Ease Jam at Coliseum COLUMBUS CIRCLE TO SHIFT TRAFFIC Bus Routes to be Changed Six Months of Study". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-02-13.

- 1 2 Lombino, David (June 28, 2005). "Two Years and $20M Later, Traffic-Plagued Columbus Circle Near Completion". The New York Sun. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Newman, Andy (August 11, 1998). "Traffic on Columbus Circle Finally Comes, Well, Full Circle". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- 1 2 "ASLA 2006 Professional Awards". American Society of Landscape Architects. 2006. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Jacobs, Karrie (April 21, 2009). "The New Time Warner Center". Travel + Leisure. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ↑ Garlock, Stephanie (June 27, 2014). "The Sign Says You've Got 72 Miles to Go Before the End of Your Road Trip. It's Lying". CityLab. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ↑ Hagstrom 25-mile radius from Columbus Circle, New York City, Hagstrom Map Company, Hagstrom Map Co, 1984, ISBN 0880971223, retrieved October 13, 2017

- ↑ Company, Hagstrom Map (March 1, 2006). Hagstrom 75-Mile Radius Map: From Columbus Circle, NYC. Hagstrom Map Company, Incorporated. ISBN 9781592459834.

- ↑ Shribman, David. "Justice Dept. Denies 315 Visas for U.N. Disarmament Session", The New York Times, June 8, 1982. Accessed October 9, 2017. "These restricted visas, known as C-2 visas, limit travel to within 25 miles of Columbus Circle in Manhattan."

- ↑ Prevost, Lisa (February 16, 2003). "Lights! Camera! Action! Location Fees!". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ↑ "25 Mile Studio Zone Map" (PDF). State of New Jersey Department of State.

- ↑ "Theatrical Agreement" (PDF). SAG-AFTRA. 2005.

- ↑ "Economic & Fiscal Impact of the Nassau County Film Industry". www.nassaucountyny.gov. March 2015. pp. 3–4.

- ↑ "FAQs: Directive #6 – Travel, Meals, Lodging, and Miscellaneous Agency Expenses" (PDF). The New York City Office of The Comptroller. August 21, 2017.

- ↑ "City Vehicle Driver Handbook" (PDF). The City of New York. May 2016.

- 1 2 3 "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Midtown West" (PDF). mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- 1 2 Google (October 13, 2017). "Columbus Cir, New York, NY" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ↑ Gray, Christopher (April 26, 1987). "The Coliseum; The 'Hybrid Pseudo-Modern' on Columbus Circle". The New York Times. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- ↑ Hudson, Edward (April 13, 1954). "COLISEUM IS BEGUN AFTER 8-YEAR LAG; Mayor and Moses Denounce Bid in Congress to Bar Aid -- Will Take Fight to Capital WON'T LET U. S. RENEGE' Fear Expressed That Plan, if Passed, Would Endanger $200,000,000 Projects". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Blair, William G. (May 3, 1985). "14 PLANS FOR COLISEUM SITE SENT TO CITY AND M.T.A." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (February 20, 2000). "Built, but Not Destined, to Last; A Robert Moses Legacy, Coliseum Is Coming Down". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot & Leadon, Fran (2010), AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.), New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195383867

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (2003). "A Vertical Neighborhood Takes Shape". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Crow, Kelly. "The Newest Tower: Working 24/7", The New York Times, December 9, 2001. Accessed October 9, 2017. "ON the western rim of Columbus Circle, on the site of the old Coliseum, stands the skeleton of the city's newest skyscraper, the AOL Time Warner Center. At the moment, it is a mesh of steel and scaffolding 19 stories tall, but when completed in two years, the $1.7 billion center's twin towers will reach 53 stories, or 750 feet."

- ↑ Ensminger, Kris (October 9, 2005). "Columbus Circle: A New World". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ "Dining". The Shops at Columbus Circle. 2017.

- ↑ Pogrebin, Roin. "52-Story Comeback Is So Very Trump; Columbus Circle Tower Proclaims That Modesty Is an Overrated Virtue", The New York Times, April 25, 1996. Accessed October 9, 2017. "The Trump International Hotel and Tower is open for business, looming over Columbus Circle and Central Park like a ghost of the Gulf and Western Building, which is precisely what it is. And with his new building, due for occupancy in the fall, Donald Trump seems to be busily renovating himself in much the same way: as himself -- only more so."

- 1 2 Rothstein, Mervyn (January 31, 1993). "COMMERCIAL PROPERTY: The Gulf ands Western Building; Twisting in the Wind On Columbus Circle". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (July 17, 1994). "For a Troubled Building, a New Twist". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Muschamp, Herbert (June 21, 1995). "Trump Tries to Convert 50's Style Into 90's Gold; Makeover Starts on Columbus Circle Hotel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ "New Trump Hotel On Central Park". The New York Times. 1997. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- 1 2 USS Maine National Monument, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Accessed October 9, 2017.

- ↑ "MONUMENT TO MAINE HEROES READY FOR UNVEILING; Distinguished Guests and Imposing Ceremonies at the Dedication on Memorial Day---Fleet of Seventeen Ships and 5,000 Bluejackets Will Participate" (PDF). The New York Times. May 25, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Harding, Alfred. "AFTER A STORMY YOUTH EQUITY COMES OF AGE; EQUITY REACHES THE AGE OF TWENTY-ONE", The New York Times, May 27, 1934. Accssed October 9, 2017. "TWENTY-ONE years ago yesterday, on May 26, 1913, 110 actors met in Elks Hall, in the Pabst Grand Circle Hotel on West Fifty-ninth Street, and, by their signature of the members' agreement and constitution and by-laws of the Actor Equity Association, laid the cornerstone of one of the most significant structures in the American theatre."

- 1 2 3 Muschamp, Herbert. "The Secret History of 2 Columbus Circle", The New York Times, January 8, 2006. Accessed October 9, 2017.

- ↑ "100 Most Endangered Sites 2006" (PDF). World Monuments Fund: 47. Summer 2005.

- ↑ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (September 25, 2008). "Brad Cloepfil's Museum of Arts and Design Gives a Building a New Face and Restores Its Original Mission". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Pogrebin, Robin (December 1, 2008). "Preservation and Development, Engaged in a Delicate Dance". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ↑ Wolfe, Tom (July 4, 2005). "The 2 Columbus Circle Game". New York Magazine. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Hales, Linda (June 13, 2004). "Columbus Circle site sets off a controversy". Washington Post. Retrieved October 14, 2017 – via Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009), Postal, Matthew A., ed., Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1

- 1 2 Neamt, Ioana (February 18, 2016). "Nordstrom's Future New York Store is an Eyecatcher". Commercial Property Executive. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ "U.S. Rubber Company Building, New York City". Emporis. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- 1 2 Gray, Christopher (November 26, 1989). "Streetscapes: U.S. Rubber Company Building; Restoring Luster to a 1912 Lady". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- 1 2 Dunlap, David W. (July 7, 2000). "Street of Automotive Dreams". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Wilson, Reid (February 12, 2016). "Official Renderings Revealed Of Nordstrom Tower's Retail Base Under Construction At 217 West 57th Street". New York YIMBY. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Warerkar, Tanay (February 12, 2016). "Central Park Tower's Nordstrom Flagship Gets Its First Render". Curbed NY. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ "3 Columbus Circle, New York City". Emporis. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ "3 Columbus Circle". The Real Deal New York. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dunlap, David W. (February 20, 2008). "Switching Brands in the Skyline". City Room. The New York Times. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ "COLONNADE BUILDING AT COLUMBUS CIRCLE WILL BE IMPORTANT COMMERCIAL IMPROVEMENT; Planned for Twenty-three Stories and Will Be Erected on the Block Now Occupied by the Thoroughfare Building in the Heart of the Motor Trade Activity-- Total Cost Will Exceed $6,000,000 MOONSHINING IN BUILDINGS. Owner Liable for Fine Imposed Upon a Tenant" (PDF). The New York Times. February 27, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ "NOYES & CO. CLOSE $24,000,000 DEAL" (PDF). Brooklyn Standard Union. February 9, 1926. p. 16 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- 1 2 3 Oser, Alan S. (September 15, 1999). "Commercial Real Estate; Developer Is Stepping Up Its Activity in West Midtown Area". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- 1 2 Clarke, Katherine (July 30, 2015). "Neon CNN sign removed from Columbus Circle perch after 10 years". NY Daily News. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Piskora, Beth (August 26, 1999). "NEWSWEEK BUILDING SOLD FOR $140 MILLION". New York Post. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- 1 2 Cuozzo, Steve (December 27, 2007). "BROADWAY BONANZA". New York Post. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Strassel, Kimberley A. (August 25, 1999). "David Werner Is Set to Purchase Manhattan's Newsweek Building". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ "4 Columbus Circle". The Real Deal New York. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Fung, Amanda (August 3, 2011). "Germans pay $96.5M for 4 Columbus Circle". Crain's New York Business. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Conlin, Jennifer (July 1, 2007). "Anticipation Builds, and Builds Some More, for Latest Chic New York Hotel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Hylton, Ondel (January 12, 2016). "See How 6 Columbus Circle Could Change the Central Park Skyline". 6sqft. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ "6 Columbus Circle Hotel Site Hits the Market, Expected to Fetch $88.9M". Commercial Observer. December 1, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ Baird-Remba, Rebecca (January 8, 2016). "Vision: A 700-Foot-Tall Tower for 6 Columbus Circle?". New York YIMBY. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ↑ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. December 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. January 18, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ↑ Carr, Nick. 'New York, You’ve Changed: Taxi Driver , Part III", Huffington Post, March 18, 2010, updated December 6, 2017. Accessed September 27, 2018. "Charlie goes to the Palantine rally at Columbus Circle in what proves to be a failed attempt to assassinate the candidate:"

Bibliography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Columbus Circle. |

- NYC Parks Department - Columbus Circle

- NYC Parks Department - Columbus Monument

- NYCDOT traffic cams facing Columbus Circle

- Smithsonian's Inventory of American Sculpture Entry

.png)