1 Esdras

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bible portal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

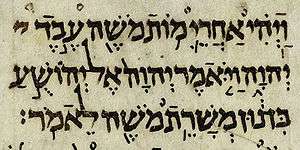

1 Esdras (Greek: Ἔσδρας Αʹ), also Greek Esdras, Greek Ezra, or 3 Esdras, is an ancient Greek version of the biblical Book of Ezra in use among the early church, and many modern Christians with varying degrees of canonicity. First Esdras is substantially the same as Masoretic Ezra.

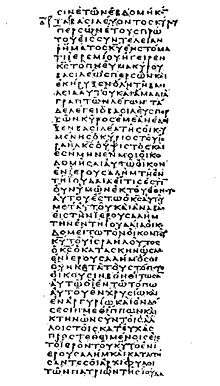

As part of the Septuagint translation of the Old Testament, it is regarded as canonical in the churches of the East, but apocryphal in the West.[1] First Esdras is found in Origen's Hexapla. Greek and related versions of the Bible include both Esdras Αʹ (English title: 1 Esdras) and Esdras Βʹ (Ezra–Nehemiah) in parallel.

Overwhelmingly, citations from the scriptural 'Book of Ezra' in early Christian writings are taken from 1 Esdras; especially from the 'Tale of the Three Guardsmen', which is interpreted as Christological prophecy.

Contents

First Esdras contains the whole of Ezra with the addition of one section; its verses are numbered differently. Just as Ezra begins with the last two verses of 2 Chronicles, 1 Esdras begins with the last two chapters; this suggests that Chronicles and Esdras may have been read as one book at sometime in the past.

Ezra 4:6 includes a reference to a King Ahasuerus. Etymologically, Ahasuerus is the same as Xerxes, who reigned between Darius I and Artaxerxes I. Eighteenth-century expositor John Gill, who deemed the reference to Xerxes out of place, identified Ahasuerus with Cambyses II.[2] Nineteenth-century commentator Adam Clarke identified him with Bardiya, who both reigned before Darius I.[3] In 1 Esdras, the section is reorganized, leading up to the additional section, and the reference to Ahasuerus is removed.

The additional section begins with a story variously known as the 'Darius contest' or 'Tale of the Three Guardsmen' which was interpolated into 1 Esdras 3:4 to 4:4.[4] This section forms the core of 1 Esdras with Ezra 5, which together are arranged in a literary chiasm around the celebration in Jerusalem at the exiles’ return. This chiastic core forms 1 Esdras into a complete literary unit, allowing it to stand independently from the book of Nehemiah. Indeed, some scholars, such as W. F. Albright and Edwin M. Yamauchi, believe that Nehemiah came back to Jerusalem before Ezra.[5][6]

| EZRA AND I ESDRAS COMPARED | ||

|---|---|---|

| Masoretic Text | Septuagint | Summary |

| Continuation of Paralipomenon (i.e., "Things Set Off" from Esdras) | ||

| (II Chr. 35) | (I Esd. 1:1-33) | |

| (II Chr. 36) | (I Esd. 1:34-58) | |

| Begin Ezra | ||

| Ezr. 1 | I Esd. 2:1-14 | Cyrus's edict to rebuild the Temple |

| Ezr. 4:7-24 | I Esd. 2:15-30a | Flash forward to Artaxerxes’ reign (prolepsis) |

| Core: Chiasm of Celebration | ||

| — | I Esd. 2:30b | Inclusio: Work hindered until second year of Darius’s reign |

| — | I Esd. 3 | A Feast in the court of Darius with Darius contest |

| — | I Esd. 4 | B Darius vows to repatriate the exiles |

| — | I Esd. 5:1-6 | X The feast of those who returned to Jerusalem |

| Ezr. 2 | I Esd. 5:7-46 | B' List of former exiles who returned |

| Ezr. 3 | I Esd. 5:47-65 | A' Feast of Tabernacles |

| Ezr. 4:1-5[7] | I Esd. 5:66-73 | Inclusio: Work hindered until second year of Darius’s reign |

| Conclusion | ||

| Ezr. 5 | I Esd. 6:1-22 | In the second year of Darius's reign |

| Ezr. 6 | I Esd. 6:23 — 7 | The temple is finished |

| Ezr. 7 | I Esd. 8:1-27 | In Artaxerxes’ reign |

| Ezr. 8 | I Esd. 8:28-67 | List of latter exiles who returned |

| Ezr. 9 | I Esd. 8:68-90 | Repentance from miscegenation |

| Ezr. 10 | I Esd. 8:91-9:36 | Putting away of foreign wives and children |

| (Neh. 7:73-8:12) | (I Esd. 9:37-55) | |

Author and criticism

The purpose of the book seems to be the presentation of the dispute among the courtiers, the 'Tale of the Three Guardsmen', to which details from the other books are added to complete the story. Since there are various discrepancies in the account, most scholars hold that the work was written by more than one author. However, some scholars believe that this work may have been the original, or at least the more authoritative; the variances that are contained in this work are so striking that more research is being conducted. Furthermore, there is disagreement as to what the original language of the work was, Greek, Aramaic, or Hebrew. Because of similarities to the vocabulary in the Book of Daniel, it is presumed by some that the authors came from Lower Egypt and some or all may have even had a hand in the translation of Daniel. Assuming this theory is correct, many scholars consider the possibility that one chronicler wrote this book.

Josephus makes use of the 1 Esdras which he treats as Scripture, while generally disregarding the canonical text of Ezra-Nehemiah. Some scholars believe that the composition is likely to have taken place in the first century BC or the first century AD. Many Protestant and Catholic scholars assign no historical value to the sections of the book not duplicated in Ezra-Nehemiah. The citations of the other books of the Bible, however, provide an early alternative to the Septuagint for those texts, which increases its value to scholars.

In the current Greek texts, the book breaks off in the middle of a sentence; that particular verse thus had to be reconstructed from an early Latin translation. However, it is generally presumed that the original work extended to the Feast of Tabernacles, as described in Nehemiah 8:13–18. An additional difficulty with the text appears to readers who are unfamiliar with chiastic structures common in Semitic literature. If the text is assumed to be a Western-style, purely linear narrative, then Artaxerxes seems to be mentioned before Darius, who is mentioned before Cyrus. (Such jumbling of the order of events, however, is also presumed by some readers to exist in the canonical Ezra and Nehemiah.) The Semitic chiasm is corrected in at least one manuscript of Josephus in the Antiquities of the Jews, Book 11, chapter 2 where we find that the name of the above-mentioned Artaxerxes is called Cambyses.

Use in the Christian canon

The book was widely quoted by early Christian authors and it found a place in Origen's Hexapla. Jerome states that it is apocryphal along with 4 Esdras.[8] Clement VIII placed it in an appendix to the Vulgate with other apocrypha "lest they perish entirely".[9] However, the use of the book continued in the Eastern Church, and it remains a part of the Eastern Orthodox canon.

The Old Latin version of First Esdras, as witnessed in the Codex Colbertinus is an entirely independent (and probably later) translation of the Greek Esdras A, as compared with the Latin text of 3 Esdras witnessed in most medieval Vulgate manuscripts and the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate. Where the Vulgate text of First Esdras is woodenly literal in its rendering of the Greek, the Old Latin text tends towards free paraphrase.[10]

In the Roman rite liturgy, the book is cited once in the Extraordinary Missal of 1962 in the Offertory of the votive Mass for the election of a Pope. “Non participentur sancta, donec exsurgat póntifex in ostensiónem et veritátem. – Let them not take part in the holy things, until there arise a priest unto showing and truth.” (3 Esdras 5, 40).[11]

Some scholars, including Joseph Blenkinsopp in his 1988 commentary on Ezra–Nehemiah, hold that the book is a late 2nd/early 1st century BC revision of Esdras and Esdras β,[12] while others such as L. L. Grabbe believe it to be independent of the Hebrew-language Ezra-Nehemiah.[13]

Nomenclature

The book normally called 1 Esdras is numbered differently among various versions of the Bible. In most editions of the Septuagint, the book is titled in Greek: Ἔσδρας Αʹ and is placed before the single book of Ezra–Nehemiah, which is titled in Greek: Ἔσδρας Βʹ.

Summary

- Septuagint and its derivative translations: Ἔσδρας Αʹ = 1 Esdras

- King James Version and many[14] successive English translations: 1 Esdras

- Clementine Vulgate and its derivative translations: 3 Esdras

- Slavonic Bible: 2 Esdras

- Ethiopic Bible: Ezra Kali[15]

See also

References

- ↑ For example, it is listed among the Apocrypha in Article VI of the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England. Read Article VI at episcopalian.org Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Gill's Exposition of the Whole Bible, as quoted by Bible.cc/ezra/4-7.htm

- ↑ Clarke's Commentary on the Bible, as quoted by Bible.cc/ezra/4-7.htm

- ↑ Charles C. Torrey (1910). Ezra Studies. University of Chicago Press. p. 58.

- ↑ W. F. Albright, "The Date and Personality of the Chronicler", JBL 40 (1921), 121. Full text.

- ↑ Edwin Yamauchi, "The Reverse Order of Ezra/Nehemiah Reconsidered," Themelios 5.3 (1980), 7-13. Full text.

- ↑ Ezra 4:6, which introduces a difficult "King Ahasuerus," is not found in I Esdras.

- ↑ "St. Jerome, The Prologue on the Book of Ezra: English translation".

- ↑ Liber Esdrae Tertius Apocrypha.

- ↑ The Latin Versions of First Esdras, Harry Clinton York, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Jul., 1910), pp. 253-302

- ↑

- ↑ Blenkinsopp, Joseph, "Ezra-Nehemiah: A Commentary" (Eerdmans, 1988) pp.70–71

- ↑ Grabbe, L.L., "A history of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period, Volume 1" (T&T Clark, 2004) p.83

- ↑ Including RSV, NRSV, NEB, REB, and GNB

- ↑ Ethiopian Ezra Kali means "2 Ezra".

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: 1 Esdras |

| Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Full text of 1 Esdras from the University of Virginia's Etext Center

- Various translations of 1 Esdras at the World Wide Study Bible

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Esdras: THE BOOKS OF ESDRAS: III Esdras

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Esdras, Books of: I Esdras

- 1 Esdras 1 – NRSV

- 1 Esdras at Early Jewish Writings

- 1 Ezra: 2012 Critical Translation with Audio Drama at biblicalaudio

| Deuterocanon | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by 1–2 Chronicles |

E. Orthodox Books of the Bible |

Succeeded by Ezra-Nehemiah (2 Esdras) |