Army of the Han dynasty

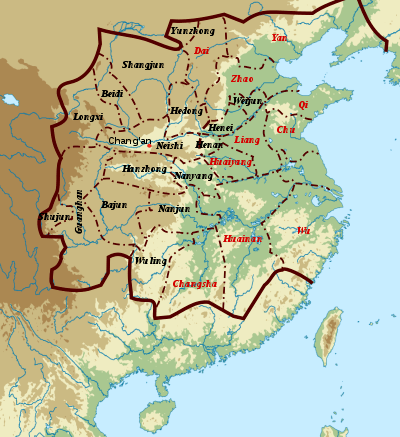

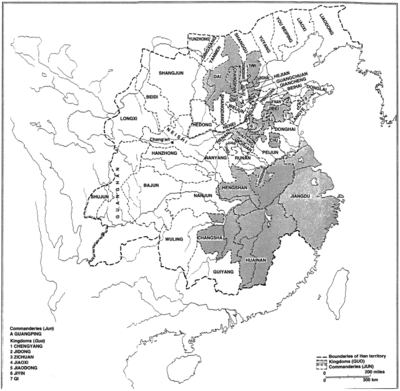

The army of the Han dynasty was the primary military apparatus of China from 202 BC to 220 AD, with a brief interregnum by the reign of Wang Mang and his Xin dynasty from 9 AD to 23 AD, followed by two years of civil war before the refounding of the Han.

Organization

Recruitment and training

At the start of the Han dynasty, male commoners were liable for conscription starting from the age of 23 until the age of 56. The minimum age was lowered to 20 after 155 BC, briefly raised to 23 again during the reign of Emperor Zhao of Han (r. 87–74 BC), but returned to 20 afterwards. Some convicts could also choose to commute their service by serving on the frontier. Conscripts trained for one year and then served for another year either on the frontier, in one of the provinces, or at the capital as guards. A relatively small minority of these conscripts would also have served in the cavalry division in the north, which was primarily composed of volunteers from families of superior status, or water borne forces in the south.[1] Conscripts were generally trained to arrange themselves in a formation five men deep.[2] After finishing their two years of service, the conscripts were discharged. During Western Han times discharged conscripts could still be called up for training once a year but this practice was discontinued after 30 AD.[3]

Certain noble were exempt from military conscription. Those of ranks four to eight did not have to perform service in their locality and those of rank 9 and higher had full exemptions.[3] During the Eastern Han period, commoners were allowed to commute military service by paying a scutage tax.[4]

Frontier life

The efficiency of these garrisons was kept at a high professional standard. Officers arbitrated disputes between servicemen, who could plead for the recovery of debts. In the orderly rooms of the companies meticulous records were kept of the daily work on which men were engaged; of the preparation, dispatch, and receipt of official mail; of the regular tests in archery to which officers were subject; and of the inspectors’ reports on the state of efficiency of sites and equipment. Accurate timekeeping was a feature of service life, as may be seen, for example, in the records of schedules for the delivery of mail; of the observation of routine signals; and of the passage of individuals through points of control. Similarly, careful accounts were kept of the official expenditure and distribution of supplies; of payments made for officers' stipends or for the purchase of stores such as glue, grease, or cloth; of the rations of grain and salt to which men and their families were entitled; of the receipt of equipment and clothing by the men; and of the equipment, weapons, and horses consigned to the care of the units.[5]

— Michael Loewe

Professional army

The Northern Army was a professional force of full time soldiers which had existed since 180 BC. It originally consisted of eight regiments and around 8,000 troops, but was later reorganized from 31 to 39 AD into a smaller force of five regiments, around 4,200 troops. The five regiments were each commanded by a colonel: the colonel of garrison cavalry, the colonel of picked cavalry, the colonel of infantry, the colonel of Chang River, and the colonel of archers. A captain of the center inspected the Northern Army and their encampments.[6][7][8]

There was also a Southern Army, created in 138 BC, with a total force of 6,000 troops. However the soldiers rotated in and out every year so they are not considered a professional force[7][3]

In 188 AD an "Army of the Western Garden" was created from the private troops of a collection of warlords as a counterweight to the Northern Army.[9]

According to Rafe de Crespigny, the total number of professional soldiers in the Eastern Han, including all the smaller groups, amounted to some 20,000 soldiers.[10]

| Army (軍 jun) | Inspector | Commander | Regiment (部 bu) | Troops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Army (北軍 beijun) | Captain of the center (北軍中候 beijun zhonghou) | Colonel (校尉 xiaowei) | Picked cavalry (越騎 yueji) | 900 |

| Colonel (校尉 xiaowei) | Garrison cavalry (屯騎 tunji) | 900 | ||

| Colonel (校尉 xiaowei) | Archers who shoot at sound (射聲 shesheng) | 900 | ||

| Colonel (校尉 xiaowei) | Foot soldiers (步兵 bubing) | 900 | ||

| Colonel (校尉 xiaowei) | Chang River (長水 changshui) | 900 |

| Title | Function | Troops |

|---|---|---|

| Bearer of the gilded mace (執金吾 zhijinwu) | Capital police | 2,000 cavalrymen 1,000 halberdiers |

| Colonel of the city gates (城門校尉 chengmen xiaowei) | Gate garrisons | 2,000 |

| Rapid as tigers (虎賁 huben) | Hereditary guard | 1,500 |

| Feathered Forest (羽林 yulin) | Recruits from the sons and grandsons of fallen soldiers | 1,700 |

Officers

Neither the Qin or Han armies had permanent generals or officers. They were chosen on an ad hoc basis and appointed directly by the emperor as the need arose. At times several generals were given control of expeditionary forces to prevent any one general from obtaining overwhelming power and rebelling. A general's stipends were equivalent or slightly below that of the Nine Ministers, but in the case of failure on campaign, a general could face very severe penalties such as execution. Smaller forces were led a colonel (xiaowei) [11]

| General (將軍 jiangjun) | Lieutenant-general (偏將軍 pian jiangjun) Commandant (都慰 duwei) | Colonel (校尉 xiaowei) | Major (司馬 sima) | Captain of the army (軍候 junhou) | Platoon chief (屯長 tunzhang) |

Logistics

According to Zhao Chongguo who served in the first century BC, a force of 10,281 men required 27,363 hu of grain and 308 hu of salt each month, requiring a convoy of 1,500 carts for transport. One hu is 19.968 liters, meaning that each soldier required per month 51.9 liters of grain and 0.6 liters of salt. Another document at Juyan suggests 3.2 hu, or 63.8 liters, of grain.[12]

Decline

When imperial authority collapsed after 189 AD, military governors reverted to relying upon their personal retainers as troops. Due to the ensuing chaos of the Three Kingdoms period, there was no need for conscription since displaced peoples voluntarily enlisted in the army for security reasons.[13][14] The end of the Han system of recruitment eventually led to the rise of a hereditary military class by the beginning of the Jin dynasty (265–420).[15]

The internecine conflicts that dominated the Chinese scene during the century after 180 transformed the economy and gave rise to new relationships between elite families and the farming population; they greatly weakened, but did not destroy, the centralized structure of imperial government. At the same time, they also saw the emergence of new forms of military service and military organization. The most important of these changes were the creation of a dependent, hereditary military caste that was clearly distinguished from the general population, an increasing reliance on cavalry forces of non-Chinese, “barbarian” origin, and the development of command structures that left tremendous authority in the hands of local and regional military leaders. All of these developments amounted to the negation of the early Western Han military system that had been based on universal service and temporary, ad hoc command arrangements.[15]

— David Graff

Chariots and horses

Although the chariot started losing prominence around the late Warring States period, it remained in use into the Han era until the Xiongnu war of 133 BC when they proved too slow to catch up to an all cavalry force.[16]

The Han's cavalry forces were fairly limited at the beginning of the dynasty. Their only large scale horse breeding programs existed in cities along northwest China: Tianshui, Longxi, Anding, Beidi, Shang, and Xihe. Emperor Wen of Han (r. 180–157 BC) decreed that three men of age could be exempted from military service for each horse sent by the family to the government. Emperor Jing of Han (r. 157–141 BC) set up 36 government pastures in the northwest to breed horses for military use and sent 30,000 slaves to care for them. By the time Emperor Wu of Han (r. 9 March 141 BC – 29 March 87 BC) came to power, the Han government had control over herds of roughly 300,000 horses, which increased to over 450,000 under Emperor Wu's reign.[17] On paper, the Han dynasty at its height was capable of fielding up to 300,000 horsemen, but was probably constrained by their immense upkeep. A cavalryman on average cost 87,000 cash, not including rations, while a regular soldier only 10,000 cash. The total expenditure of a 300,000 strong cavalry force would therefore have been around 2.18 times the entire government's annual revenue.[18]

Single mounting stirrups were used, but full double stirrups didn't appear until the later Jin dynasty (265–420).[19]

| Zhao (WS) | Warring States | Qin | Han | Ming |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8% | 2% | 6% | 36% | 3% |

Armour

Han armour was largely the same as the Qin dynasty with minor variations. Infantry wore suits of rawhide, hardened leather, or iron lamellar armour and caps or iron helmets. Some riders wore armour and carried shields but substantial horse armour is not attested to until the late 2nd century.[20]

| Item | Inventory | Imperial Heirloom |

|---|---|---|

| Jia armour | 142,701 | 34,265 |

| Kai armour | 63,324 | |

| Thigh armour | 10,563 | |

| Iron thigh armour | 256 | |

| Iron lamellar armour (pieces?) | 587,299 | |

| Helmets | 98,226 | |

| Horse armour | 5,330 | |

| Shields | 102,551 |

During the late 2nd century BC, the government created a monopoly on the ironworks, which may have caused a decrease in quality of iron and armour. Bu Shi claimed that the resulting products were inferior because they were made to meet quotas rather than for practical use. These monopolies as debated in the Discourses on Salt and Iron were abolished by the beginning of the 1st century AD. In 150 AD, Cui Shi made similar complaints about the issue of quality control in government production due to corruption: "...not long thereafter the overseers stopped being attentive, and the wrong men have been promoted by Imperial decree. Greedy officers fight over the materials, and shifty craftsmen cheat them... Iron [i.e. steel] is quenched in vinegar, making it brittle and easy to... [?] The suits of armour are too small and do not fit properly."[21]

Composite bows were considered effective against unarmoured enemies at 165 yards, and against armoured opponents at 65 yards.[19]

Chinese sources don't explicitly reference the use of a shield wall tactic or the testudo, but there do exist references to "great shields" which were used on the front line to protect spearmen and crossbowmen. Shields were also commonly paired with the single edged dao and used among cavalrymen.[22]

Two types of Han lamellar armour

Two types of Han lamellar armour Han iron scale or lamellar armour

Han iron scale or lamellar armour Han lamellar armour type 1

Han lamellar armour type 1 Han lamellar armour type 2

Han lamellar armour type 2 Han iron helmet

Han iron helmet Han shieldbearer

Han shieldbearer Han horseman with shield

Han horseman with shield

Swords and polearms

The jian was mentioned as one of the "Five Weapons" during the Han dynasty, the other four being dao, spear, halberd, and staff. Another version of the Five Weapons lists the bow and crossbow as one weapon, the jian and dao as one weapon, in addition to halberd, shield, and armour.[23]

The jian was a popular weapon during the Han era and there emerged a class of swordsmen who made their living through fencing. Sword fencing was also a popular pastime for aristocrats. A 37 chapter manual known as the Way of the Jian is known to have existed, but is no longer extant. South and central China were said to have produced the best swordsmen.[24]

There existed a weapon called the "Horse Beheading Jian", so called because it was supposedly able to cut off a horse's head.[25] However, another source says that it was an execution tool used on special occasions rather than a military weapon.[26]

Daos with ring pommels also became widespread as a cavalry weapon during the Han era. The dao had the advantage of being single edged, which meant the dull side could be thickened to strengthen the sword, making it less prone to breaking. When paired with a shield, the dao made for a practical replacement for the jian, hence it became the more popular choice as time went on. After the Han, sword dances using the dao rather than the jian are mentioned to have occurred. Archaeological samples range from 86 to 114 cm in length.[27]

| Item | Inventory | Imperial Heirloom |

|---|---|---|

| Bronze dagger-axe | 632 | 563 |

| Spear | 52,555 | 2,377 |

| Long lance (pi) | 451,222 | 1,421 |

| Long lance (sha) | 24,167 | |

| Halberd or Ji | 6,634 | |

| Jian | 99,905 | 4 |

| Dao | 156,135 | |

| Sawing dao | 30,098 | |

| Great dao | 127 | 232 |

| Iron axe | 1,132 | 136 |

| Dagger | 24,804 | |

| Shield | 102,551 | |

| Crossbow | 537,707 | 11,181 |

| Bow | 77,52 | |

| Bolts | 11,458,424 | 34,265 |

| Arrows | 1,199,316 | 511 |

| Youfang (no idea what this is) | 78,393 |

An account of Duan Jiong's tactical formation in 167 AD specifies that he arranged "…three ranks of halberds (長鏃 changzu), swordsmen (利刃 liren) and spearmen (長矛 changmao), supported by crossbows (強弩 qiangnu), with light cavalry (輕騎 jingji) on each wing."[28]

The characters zu and mao both indicate lances or spears, but I suspect the changzu may have had two blades or points. Such weapons, commonly identified as 戟 ji, but also as 鈹 pi and 錟 tan, have been known from early times. Some bronze horsemen found in the tomb at Leitai 雷台 by present-day Wuwei are armed with halberds. An alternative rendering for changzu would be “javelin,” but javelins were not common in ancient China.[28]

— Rafe de Crespigny

Han dynasty jians. The longest is 146 cm in length.

Han dynasty jians. The longest is 146 cm in length. Han jian and scabbard.

Han jian and scabbard. Han dao, jian, and halberd

Han dao, jian, and halberd Han iron halberd

Han iron halberd Han Great Dao

Han Great Dao Eastern Han sword-staff. The blade is 62 cm long, 5.2 cm wide, and 1.2 cm thick. The hilt is 19 cm long. These were often attached to shafts and used as polearms.

Eastern Han sword-staff. The blade is 62 cm long, 5.2 cm wide, and 1.2 cm thick. The hilt is 19 cm long. These were often attached to shafts and used as polearms.

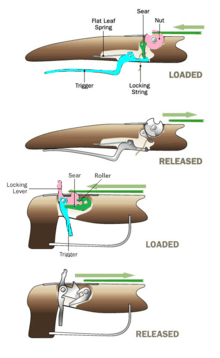

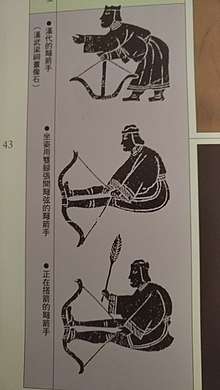

Crossbow

It's clear from surviving inventory lists in Gansu and Xinjiang that the crossbow was greatly favored by the Han dynasty. For example in one batch of slips there are only two mentions of bows, but thirty mentions of crossbows.[29] Crossbows were mass-produced using material such as mulberry wood and brass; a crossbow in 1068 could pierce a tree at 140 paces.[30] Crossbows were used in numbers as large as 50,000 starting from the Qin dynasty and upwards of several hundred thousand during the Han.[31] According to one authority the crossbow had become "nothing less than the standard weapon of the Han armies" by the second century BC.[32] Han era carved stone images and paintings also contain images of horsemen wielding crossbows. Han soldiers were required to pull an "entry level" crossbow with a draw-weight of 76kg to qualify as a crossbowman.[33]

The Huainanzi advises its readers not to use crossbows in marshland where the surface is soft and it is hard to arm the crossbow with the foot.[29] The Records of the Grand Historian, completed in 94 BC, mentions that Sun Bin defeated Pang Juan by ambushing him with a body of crossbowmen at the Battle of Maling.[34] The Book of Han, finished 111 AD, lists two military treatises on crossbows.[35]

In the 2nd century AD, Chen Yin gave advice on shooting with a crossbow in the Wuyue Chunqiu:

When shooting, the body should be as steady as a board, and the head mobile like an egg [on a table]; the left foot [forward] and the right foot perpendicular to it; the left hand as if leaning against a branch, the right hand as if embracing a child. Then grip the crossbow and take a sight on the enemy, hold the breath and swallow, then breathe out as soon as you have released [the arrow]; in this way you will be unperturbable. Thus after deep concentration, the two things separate, the [arrow] going, and the [bow] staying. When the right hand moves the trigger [in releasing the arrow] the left hand should not know it. One body, yet different functions [of parts], like a man and a girl well matched; such is the Dao of holding the crossbow and shooting accurately.[36]

— Chen Yin

The crossbow was particularly effective against cavalry charges for two reasons. One, the crossbow could shoot further and harder than the bows of the Xiongnu, and two, even if the enemy went back to collect the quarrels, they had no way of using them because they were too short for their bows.

In 169 BC, Chao Cuo observed that by using the crossbow, it was possible to overcome the Xiongnu:

Of course, in mounted archery [using the short bow] the Yi and the Di are skilful, but the Chinese are good at using nu che. These carriages can be drawn up in the form of a laager which cannot be penetrated by cavalry. Moreover, the crossbows can shoot their bolts to a considerable range, and do more harm [lit. penetrate deeper] than those of the short bow. And again, if the crossbow bolts are picked up by the barbarians they have no way of making use of them. Recently the crossbow has unfortunately fallen into some neglect; we must carefully consider this... The strong crossbow [jing nu] and the [arcuballista shooting] javelins have a long range; something which the bows of the Huns can no way equal. The use of sharp weapons with long and short handles by disciplined companies of armoured soldiers in various combinations, including the drill of crossbow men alternately advancing [to shoot] and retiring [to load]; this is something which the Huns cannot even face. The troops with crossbows ride forward [cai guan shou] and shoot off all their bolts in one direction; this is something which the leather armour and wooden shields of the Huns cannot resist. Then the [horse-archers] dismount and fight forward on foot with sword and bill; this is something which the Huns do not know how to do.[37]

— Chao Cuo

Special crossbows

In 99 BC, mounted multiple bolt crossbows were used as field artillery against attacking nomadic cavalry.[38]

In 180 AD, Yang Xuan used a type of repeating crossbow powered by the movement of wheels:

...around A.D. 180 when Yang Xuan, Grand Protector of Lingling, attempted to suppress heavy rebel activity with badly inadequate forces. Yang's solution was to load several tens of wagons with sacks of lime and mount automatic crossbows on others. Then, deploying them into a fighting formation, he exploited the wind to engulf the enemy with clouds of lime dust, blinding them, before setting rags on the tails of the horses pulling these driverless artillery wagons alight. Directed into the enemy's heavily obscured formation, their repeating crossbows (powered by linkage with the wheels) fired repeatedly in random directions, inflicting heavy casualties. Amidst the obviously great confusion the rebels fired back furiously in self-defense, decimating each other before Yang's forces came up and largely exterminated them.[38]

— Ralph Sawyer

The invention of the repeating crossbow has often been attributed to Zhuge Liang, but he in fact had nothing to do with it. This misconception is based on a record attributing improvements to the multiple bolt crossbows to him.[39]

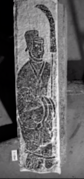

Han dynasty crossbowman using what may be a winch drawn crossbow

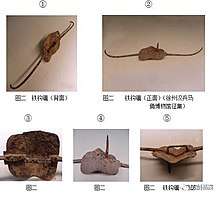

Han dynasty crossbowman using what may be a winch drawn crossbow- Ancient Chinese crossbow (2nd century BC). Guimet Museum, Paris.

Western Han (206 B.C-24 A.D.) crossbow

Western Han (206 B.C-24 A.D.) crossbow Han crossbow arming illustration

Han crossbow arming illustration Western Han crossbow trigger and butt plate

Western Han crossbow trigger and butt plate Han crossbow triggers

Han crossbow triggers

Major military campaigns and battles

Defeating the Xiongnu

In the summer of 133 BC, the Xiongnu Chanyu Junchen led a force of 100,000 to attack Mayi in Shuofang. Wang Hui and two other generals attempted to ambush them at Mayi with a large force of 300,000, but Junchen retreated after learning about the ambush from a captured local warden. Wang Hui decided not to give chase and was sentenced to death. He committed suicide.[40] The Han army abandoned chariots after this point.[16]

Chariots were still used as the chief weapon in wars against the Xiongnu during the period of Emperor Wen, and their relative lack of mobility prevented the Han force from launching any distant expeditions or gaining major victories. This fighting method survived even into the early period of Emperor Wu. For example, in his first war against the Xiongnu, in 133 B.C., a large number of war chariots were mobilized as the chief military component. But when the chanyu of the Xiongnu, realizing that he had been trickedby misinformation provided by a Han spy, retreated to his territory, the Han forces were unable to overtake him. Emperor Wu then decided to give up completely the use of war chariots.[41]

— Chun-shu Chang

In the spring of 129 BC, Wei Qing and three other generals led a cavalry force of 40,000 in an attack on the Xiongnu at the frontier markets of Shanggu. Wei Qing successfully killed several thousand Xiongnu and took 700 prisoners.[42] General Gongsun Ao was defeated and lost 7,000 men. He was reduced to commoner status.[43] Li Guang was defeated and captured but managed to escape by feigning death and returned to base. He was reduced to commoner status.[44] Gongsun He failed to find the Xiongnu.[42] That winter the Xiongnu attacked Yuyang in You Province in retaliation.[42]

In the autumn of 128 BC, Wei Qing and Li Xi led a force of 40,000 and defeated the Xiongnu north of Yanmen Commandery.[42]

In the spring of 127 BC, the Xiongnu raided Liaoxi and Yanmen Commandery. Han Anguo tried to stop them with 700 men but failed and retreated to Yuyang. When Wei Qing and two other generals arrived, the Xiongnu fled. Wei Qing pushed forward and successfully evicted the Xiongnu south of the Yellow River, killed 2,300 Xiongnu at Gaoque (Shuofang), and captured 3,075 Xiongnu and one million livestock at Fuli (Wuyuan).[45][46]

In 126 BC, the Xiongnu led a force of 90,000 under the Wise King (Dugi) of the Right to attack Dai Commandery, killing its grand administrator Gong You. They also raided Dingxiang and Shang, taking several thousand captives.[47]

In the spring of 124 BC, Wei Qing and four other generals led a force of 100,000, mostly light cavalry, against the Xiongnu. The Wise King (Dugi) of the Right assumed they would turn back after he retreated, but they did not, and he was surprised at his camp. The Han emerged victorious, capturing ten petty chieftains, 15,000 Xiongnu, and one million livestock.[45]

In the spring of 123 BC, Wei Qing and others led 100,000 cavalry against the Xiongnu, killing and capturing 3,000 north of Dingxiang. However Su Jian and Zhao Xin advanced too far with only 3,000 and were cut down. Zhao Xin defected while Su Jian managed to escape.[48][45]

In 122 BC, a Xiongnu force of 10,000 raided Shanggu.[48]

In the spring of 121 BC, Huo Qubing led a force of 10,000 cavalry and killed 8,960 Xiongnu west of the Yanzhi Mountains (in modern Gansu). In the summer he and several others marched west. Huo made it as far as the Qilian Mountains south of Jiuquan, killing and capturing 33,000 Xiongnu. The Xiongnu also invaded Yanmen Commandery so Li Guang and Zhang Qian gave chase. Li Guang was suddenly surrounded by 40,000 Xiongnu under the Wise King (Dugi) of the Left but was able to hold off repeated attacks for two days until Zhang Qian arrived and the Xiongnu retreated. Zhang Qian was demoted to commoner status for arriving late.[49][50]

In 120 BC, the Xiongnu raided Youbeiping and Dingxiang, carrying off 1,000 captives.[51]

In the summer of 119 BC, Wei Qing and Huo Qubing led a large force of 100,000 cavalry, 200,000 infantry, and 140,000 supply horses against the Xiongnu. When the Han forces arrived, they found the Xiongnu already prepared and waiting. Wei ensconced himself into a fortified ring of chariots and sent out 5,000 cavalry to probe the enemy. The Xiongnu chanyu Yizhixie responded with 10,000 cavalry. The two sides skirmished until evening when a strong wind arose, at which point Wei committed most of his cavalry and encircled the Xiongnu. Yizhixie attempted to break out of the encirclement but lost control of his men and routed. Huo's forces advanced by another route and defeated the Wise King (Dugi) of the Left. Li Guang failed to rendezvouz on time and committed suicide. A hundred thousand horses were lost during the campaign, crippling Han cavalry forces for some time.[52]

Conquering south, east, and west

In 116 BC, the Xiongnu raided Liang Province.[53]

In 113 BC, chief minister Lu Jia of Nanyue prevented its king Zhao Xing from visiting the Han court. Han Qianqiu was sent to kill Lu Jia. He advanced into Nanyue with only 2,000 men, capturing several towns, until his local allies turned on him, slaying him and his men.[54]

In 112 BC, the Han invaded eastern Tibet with 25,000 cavalry on grounds of Qiang raiding.[54]

In the autumn of 111 BC, Gongsun He and Zhao Ponu led 25,000 cavalry against the Xiongnu, but failed to engage them. Lu Bode and Yang Pu led a force of 35,000 against Nanyue.[55]

In 110 BC, Han forces defeated Nanyue and annexed the region. The king of Minyue, Zou Yushan, thought he would be attacked as well, and pre-emptively attacked Han garrisons. In the winter the Han sent another force and defeated Minyue. The area was abandoned however until further colonization in 200 AD. Emperor Wu of Han assembled his forced in Shuofang and challenged Wuwei Chanyu to meet him in battle. Wuwei declined.[56]

In 109 BC, the Han sent a force of 5,000 under Guo Chang and Wei Guang to Yelang and Dian Kingdom, forcing them to submit to the Han. A Yue rebellion led by Wu Yang resulted in the removal of all the people in Minyue further north. A Han envoy returning from Gojoseon slew his escort and claimed to have slain a general. Gojoseon retaliated by invading Liaodong.[57]

In 108 BC, a Han army of 57,000 under Xun Zhi and Yang Pu invaded Gojoseon. Xun Zhi advanced too far and was defeated. Yang Pu made it to Wanggeom-seong and was defeated. In spring they regrouped and laid siege to Wanggeom-seong. Xun Zhi got into a fight with Yang Pu and had him arrested, combining both their forces under one general. Eventually the people of the city killed their king, Ugeo of Gojoseon, and surrendered. Zhao Ponu sallied out with 25,000 cavalry against the Xiongnu but could not find them. He then attacked Loulan Kingdom and Jushi Kingdom with only 700 cavalry, subjugating them.[58]

In the autumn of 104 BC, Li Guangli led a force of 20,000 convicted conscripts and 6,000 cavalry against Dayuan. The oasis states refused to provide food so they had to attack them to procure necessities.[59]

In the summer of 103 BC, Zhao Ponu attacked the Xiongnu with 20,000 cavalry, but was surrounded and captured. Li Guangli reached Yucheng (Uzgen) but could not take the city and returned to Dunhuang.[60]

In the autumn of 102 BC, Li Guangli led a much larger army of 60,000 men, 100,000 oxen, 30,000 horses, and 20,000 supply animals against Dayuan. The oasis states surrendered and provided food upon seeing the overwhelming force. The only state which resisted was Luntai, so the entire populace was massacred. The army bypassed Yucheng (Uzgen) and headed straight for Dayuan's capital Ershi (Khujand). There the Han crossbowmen easily defeated Dayuan's army and laid siege to the city. After 40 days and diverting the river from the city, removing their water supply, the inhabitants killed their king and provided the Han army 3,000 horses. A scout force under Wang Shencheng was defeated at Yucheng (Uzgen), so Li sent a detachment under Shangguan Jie to storm Yucheng, whose king fled to Kangju. Yucheng then surrendered. Li returned with only 10,000 men.[61]

In 101 BC, the Xiongnu raided Dingxiang, Yunzhong, Zhangye, and Jiuquan.[62]

In the summer of 99 BC, Li Guangli and three other generals led a force of 35,000 against the Xiongnu in the Tian Shan range. Initially successful, Li Guangli killed some 10,000 Xiongnu, but was surrounded and had to fortify. They sortied out and managed to drive back the Xiongnu before making a run for it. The Xiongnu gave chase and dealt heavy casualties on the Han army. Li Guangli only returned with 40% of his forces. Li Ling and Lu Bode had been left further back earlier as a rear guard, but Lu Bode objected to serving under Li Ling and left. Li Ling decided to advance by himself with only 5,000 infantry, confident that his force of crossbowmen would be able to handle any force they encountered. He was confronted with a force of 30,000 Xiongnu and had to fortify behind a wagon laager between two hills. The Xiongnu made repeated charges on his position, but failed to overcome Li Ling's crossbow and shield/spear formation, suffering heavy casualties. When Li Ling's forces made a break for it, the Xiongnu chased after them, harassing them until nightfall. Only 400 men made it back and Li Ling was himself captured.[63]

In the spring of 97 BC, Li Guangli and two other generals led a force of over 160,000 against the Xiongnu. Li's forces were supposedly routed by only 10,000 Xiongnu and fought a running battle for ten days. Gongsun Ao fought an inconclusive battle with the Wise King (Dugi) of the Left. Han Yue failed to encounter any Xiongnu.[64]

In the summer of 94 BC, Xu Xiangru led a force of auxiliaries from the Western Regions against Suoju (Yarkant County) and killed their king, capturing 1,500 people.[65]

In the spring of 90 BC, Li Guangli and two other generals led a force of 79,000 against the Xiongnu. Initially successful, Li overextended and his supplies ran out, exhausting his men and horses. The Xiongnu outpaced them and dug ditches across their line of retreat. When they tried to cross the ditches, the Xiongnu fell on them, routing the entire army. Li Guangli surrendered. The other generals Shang Qiucheng and Ma Tong managed to return safely. Cheng Wan attacked Jushi Kingdom with a force of 35,000 and secured their king's surrender.[66]

In 87 BC, Wen Zhong subjugated a city near modern Islamabad.

In 83 BC, Han relinquished control over Lintun Commandery and Zhenfan Commandery.[67]

In 78 BC, Fan Mingyou led 20,000 soldiers to aid the Wuhuan against the Xiongnu, but they arrived too late, and attacked the Wuhuan instead.[68]

In 75 BC, Goguryeo took some territory from Xuantu Commandery.[69]

In 71 BC, Chang Hui and two other generals led a force of 100,000 to aid the Wusun against the Xiongnu. The majority of the forces failed to find any Xiongnu, but Chang Hui successfully aided the Wusun in defeating a Xiongnu invasion. However the Xiongnu came back in winter and took many captives. On the way back across the Altai Mountains, the Xiongnu suffered heavy casualties from a sudden blizzard, devastating their army. The next year the Xiongnu were attacked on all sides by Wusun, Wuhuan, and the Han. One third of all Xiongnu died.[70]

In 68 BC, Chang Hui led 45,000 auxiliaries from the Western Regions against Qiuci, which surrendered. Zheng Ji also subdued the Jushi Kingdom, its king having fled to the Wusun.[70]

In 65 BC, the Qiang revolted in eastern Tibet and Suoju rebelled as well. Feng Fengshi was sent in with 15,000 men and subdued Suoju.[71]

In 64 BC, the Xiongnu raided Jiaohe.[71]

In 61 BC, Zhao Chongguo advanced into eastern Tibet and set up colonies near Qinghai Lake. He also advocated for reduction of cavalry forces to reduce military expenditure.[72]

Western protectorate

In 60 BC, Xianxianchan, the Rizhu King of Jushi Kingdom, surrendered to Zheng Ji. The Western Protectorate is created and the Han gain hegemony over the western oasis states.[73]

In 58 BC, Uyan-Guidi died and the Xiongnu split up into five warring factions.[73]

In 55 BC, the Xiongnu coalesced into two groups, one under Zhizhi Chanyu and the other under his brother Huhanye.[73]

In 51 BC, Huhanye was defeated by Zhizhi Chanyu and fled to the Han.[73]

In 50 BC, Zhizhi Chanyu nominally submitted to the Han.[74]

In 48 BC, Zhizhi Chanyu declared independence after seeing the Han favor his brother Huhanye. He attacked the Wusun and based his operations in Zungaria.[74]

In 43 BC, Huhanye moved back to the north, starting the era of Western and Eastern Xiongnu.[74]

In 42 BC, the Qiang rebelled and defeated a force of 12,000 under Feng Fengshi.[75]

In 41 BC, Feng Fengshi returned to eastern Tibet with 60,000 men and crushed the Qiang rebellion.[75]

In 36 BC, Gan Yanshou and Chen Tang led a force of 40,000 against the Xiongnu. They reached Wusun territory and then advanced on Kangju. Kangju attacked them and took their wagons, but a counterattack drove off their forces, and the Han army was able to recover their supply train. Upon reaching Kangju (around modern Taraz), the army started constructing a fortified camp, but the Xiongnu attacked them. After driving off the Xiongnu with crossbows, they secured their camp and advanced on the enemy city in a shield and spear formation in front and crossbowmen behind. The crossbowmen rained down on the defenders manning the walls until they fled, then the spearmen drained the moat and started stacking firewood against the palisade. A Kangju relief force made several attacks on the Han position at night, delaying the assault and allowing the defenders to repair their walls. When the Han army attacked, the city fell with ease and Zhizhi Chanyu was stabbed to death. During this battle, an infantry unit on the Kangju side used a formation described as having the appearance of fish scales, which has caused speculation that they were Roman legionaires captured at Carrhae. Evidence is inconclusive.[76]

In 12 BC, Duan Huizong led a force to Wusun and resolved a dispute.[77]

In 6 AD, a petty king in the area of the former Jushi Kingdom defected to the Xiongnu, who turned him over to the Han.[78]

In 7 AD, the Han convinced the Wuhuan to stop sending tribute to the Xiongnu, who immediately attacked and defeated the Wuhuan.[78]

In 9 AD, Wang Mang proclaimed himself emperor of the Xin dynasty.[78]

In 10 AD, some officers of the Protector General Dan Qin rebelled, slew him, and fled to the Xiongnu.[79]

In 16 AD, an army under Li Chong and Guo Qin was sent to subdue Yanqi. One contingent was ambushed and defeated but the other massacred the population of Yanqi. Other regions remained loyal along with Suoju.[80]

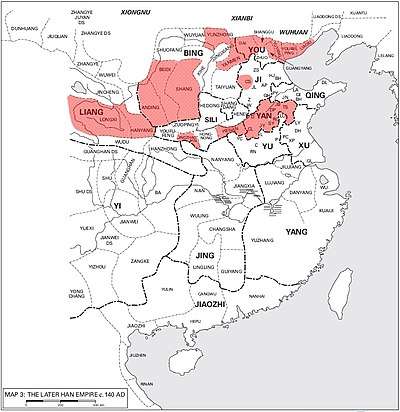

Eastern Han

In 23 AD, Wang Mang's Xin dynasty was defeated and 12 years of civil war ensued.[81]

In 35 AD, Emperor Guangwu of Han, also known as the "Bronze Horse Emperor,"[82] reunited the Han dynasty.[81]

In 40 AD, Jiuzhen, Jiaozhi, and Rinan commanderies rebelled under the Trung sisters.[83]

In 42 AD, the Trung sisters' rebellion was defeated by Ma Yuan.[84]

In 49 AD, the Qiang tribes retook the Qinghai region[85]

In 50 AD, Bi chanyu and the Southern Xiongnu settled in Bing Province.[86]

In 57 AD, the Qiang led by Dianyu raided Jincheng Commandery.[87]

In 59 AD, a Han army defeated Dianyu.[87]

In 62 AD, the Northern Xiongnu made a major raid but was repelled.[88]

In 73 AD, Dou Gu led a force of 12,000 against the Xiongnu and defeated Huyan in modern northeastern Xinjiang.[89]

In 74 AD, Dou Gu led another expedition to the Western Regions and gained the submission of Jushi, restoring the Protectorate of the Western Regions.[89]

In 75 AD, the Xiongnu besieged Jushi and Chen Mu was killed by the locals.[89]

In 77 AD, the Protectorate of the Western Regions was abandoned again.[90]

In the summer of 89 AD, Dou Xian led an army of around 45,000 against the Northern Xiongnu and defeated them. This marked the effective end of Xiongnu power in the steppes and the rise of the less organized but more aggressive Xianbei.[91]

The ideal situation on the frontier was to have a non-Chinese ruler so powerful within his own lands that his orders were obeyed but so dependent on Chinese goodwill, or vulnerable to Chinese threats, that he kept his people from troubling imperial territory. By destroying the Northern Shanyu, the Han removed a potential client and found itself faced with the incoherent but spreading power of the Xianbi, while the Southern regime was overwhelmed by its new responsibilities. So the empire destroyed a weak and all but suppliant enemy for the benefit of a junior ally who could not make good use of the victory, to the ultimate profit of a far more dangerous enemy.[92]

— Rafe de Crespigny

In 90 AD, the Protectorate of the Western Regions was restored under Ban Chao.[90]

In 107 AD, the Protectorate of the Western Regions was abandoned. A Chinese state would not gain control over the area again until the Tang dynasty.[90]

In 108 AD, the Qiang tribes raided Liang Province.[85]

In 117 AD, forces under Ren Shang ended Qiang raids.[93]

In 121 AD, the Xianbei under Qizhijian raided han territory.[94]

In 136 AD, people known as the Chulian from beyond the southern frontier attacked Rinan Commandery, causing turmoil and confusion.[95]

In 140 AD, the Qiang rebelled.[93]

In 142 AD, the Qiang rebellion was put down.[93]

In 145 AD, the Xianbei raided Dai Commandery.[96]

In 157, a rebellion occurred in Jiuzhen Commandery and was defeated.[97]

In 166 AD, the Xianbei started conducting annual raids.[98]

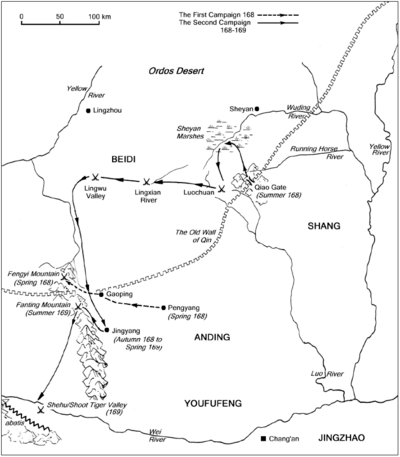

In 167 AD, Duan Jiong conducted an anti-Qiang campaign and massacred Qiang populations as well as settled them outside the frontier.[93]

In 169 AD, Geng Lin attacked Goguryeo forced the king to offer submission.[99]

In 168 AD, the Xianbei under Tanshihuai raided Han territory.[100]

In 177 AD, Xia Yu and Tian Yan led a force of 30,000 against the Xianbei. They were defeated and returned with only a quarter of their original forces.[98]

In 178 AD, Liang Long rebelled in the south.[101]

In 181 AD, Zhu Juan defeated Liang Long's rebellion.[101]

In 182 AD, the Xianbei khan Tanshihuai died and his weak successor Helian failed to keep the confederacy intact.[102]

In 184 AD, the Yellow Turban Rebellion and Liang Province rebellion erupted, leading to the fragmentation and downfall of the Han dynasty.[103]

Campaign list

Han-Xiongnu War

| Year | Aggressor | Forces | Commander | Title | Place of departure | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 BC Battle of Baideng | Han | 320,000 | Emperor Gaozu of Han | Besieged for four days until the emperor's wife bribed the Xiongnu to go away | ||

| 197 BC | Xiongnu | Raided Dai Commandery | ||||

| 196 BC | Xiongnu | Raided Dai Commandery (Canhe) | ||||

| 195 BC | Xiongnu | Raided Shanggu and eastward | ||||

| 182 BC | Xiongnu | Raided Longxi Commandery (Didao) and Tianshui (Ayang) | ||||

| 181 BC | Xiongnu | Raided Longxi Commandery (Didao) and abducted 2,000 people | ||||

| 179 BC | Xiongnu | Raided Yunzhong Commandery and plundered tribes loyal to Han | ||||

| 177 BC | Xiongnu | Conducted massacre at He'nan and Shang | ||||

| 169 BC | Xiongnu | |||||

| 166 BC | Xiongnu | 140,000 | Raided Anding (Chaona and Xiaoguan), Beidi, Anding (Pengyang), and Liang (Ganjuan Palace) Burned Huizhong Palace | |||

| 158 BC | Xiongnu | 30,000 | Raided Shang, Yunzhong Commandery, and Dai Commandery (Gouzhu) | |||

| 148 BC | Xiongnu | Raided Yan Province | ||||

| 144 BC | Xiongnu | Stole horses from Yanmen Commandery, Yunzhong Commandery (Wuchuan), and Shang | ||||

| 142 BC | Xiongnu | Attacked Yanmen Commandery and killed Governor Feng Jing | ||||

| 133 BC (Summer) Battle of Mayi | Han | 300,000 | Wang Hui Han Anguo Gongsun He Li Guang Li Zi | Failed to ambush Xiongnu Wang Hui committed suicide | ||

| 129 BC (Spring) | Han | 40,000 | Wei Qing | General of chariot and cavalry | Shanggu | Victory: Killed several thousand Xiongnu Captured 700 Xiongnu |

| Gongsun Ao | Cavalry general | Dai | Defeated: 700 men lost | |||

| Gongsun He | General of light chariot | Yunzhong | Failed to find Xiongnu | |||

| Li Guang | General of resolute cavalry | Yanmen | Captured by Xiongnu, but escaped and returned | |||

| 129 BC (Winter) | Xiongnu | Raided Shanggu, Yuyang, and killed the governor of Liaoxi | ||||

| 128 BC (Autumn) | Han | 40,000 | Wei Qing | General of chariot and cavalry | Dai | Victory |

| Li Xi | General | Dai | ||||

| 127 BC | Xiongnu | Raided Liaoxi and killed its governor Raided Yanmen and carried off several thousand men Defeated Han Anguo | ||||

| 127 BC (Spring) | Han | Wei Qing | General of chariot and cavalry | Yunzhong | Killed 2,300 Xiongnu at Gaoque (Shuofang) Captured 3,075 Xiongnu and one million livestock at Fuli (Wuyuan) | |

| Hao Xian | Governor of Shanggu | Yunzhong | ||||

| Li Xi | General | Dai | ||||

| 126 BC | Xiongnu | 90,000 | Wise king (Dugi) of the right | Raided Dai Commandery, Dingxiang, and Shang, taking several thousand slaves Killed the grand administrator of Dai Commandery, Gong You | ||

| 124 BC (Spring) | Han | 100,000 (mostly light cavalry) | Wei Qing | General of chariot and cavalry | Shuofang (Gaoque) | Captured ten petty chieftains, 15,000 Xiongnu, and one million livestock |

| Hao Xian | ||||||

| Li Suo | Colonel | |||||

| Zhao Buyu | Colonel | |||||

| Gongsun Rongnu | Colonel | |||||

| Dou Yiru | Colonel | |||||

| Li Xi | General | Yubeiping | ||||

| Zhang Cigong | General | Yubeiping | ||||

| Gongsun He | Cavalry general | Shuofang | ||||

| Su Jian | Scouting and attacking general | Shuofang | ||||

| Li Cai | General of light chariots | Shuofang | ||||

| Li Ju | General of crossbowmen | Shuofang | ||||

| Han Yue | Chief commander | |||||

| 123 BC (Spring) | Han | 100,000 cavalry | Wei Qing | General in chief | Dingxiang | Killed over 3,000 Xiongnu north of Dingxiang |

| Hao Xian | Governor of Shanggu | |||||

| Huo Qubing | Swift colonel | Killed and captured 2,228 Xiongnu | ||||

| Gongsun Ao | General of the center | |||||

| Gongsun He | General of the left | |||||

| Zhao Xin | General of the vanguard | Defeated and surrendered to Xiongnu | ||||

| Su Jian | General of the right | Defeated and escaped alone 3,000 Han soldiers killed | ||||

| Li Guang | General of the rear | |||||

| Li Ju | General of crossbowmen | |||||

| 122 BC | Xiongnu | 10,000 | Raided Shanggu | |||

| 121 BC (Spring) | Han | 10,000 cavalry | Huo Qubing | General of swift cavalry | Longxi | Killed and captured 8,960 Xiongnu west of the Yanzhi Mountains (in modern Gansu) |

| Zhao Ponu | Hawklike attacking marshal | |||||

| 121 BC (Summer) | Han | 20,000+ cavalry | Huo Qubing | Hawklike attacking marshal | Beidi | Killed and captured 33,000 Xiongnu south of Jiuquan |

| Zhao Ponu | Hawklike attacking marshal | |||||

| Gao Bushi | Colonel | Captured 1,768 Xiongnu | ||||

| Pu Peng | Colonel | Captured five Xiongnu kings | ||||

| Gongsun Ao | Marquis of Heqi | Beidi | Got lost and failed to make contact with Huo | |||

| 24,000 cavalry | Zhang Qian | Commander of the Palace Guard | Yubeiping | Was late | ||

| 4,000 cavalry | Li Guang | Chief of palace attendants | Yubeiping | Killed 3,000 Xiongnu bu lost nearly his entire force and escaped alone | ||

| 120 BC | Xiongnu | Raided Youbeiping and Xingxiang, carrying off 1,000 captives | ||||

| 119 BC (Summer) Battle of Mobei | Han | 50,000 cavalry 140,000 volunteer cavalry 200,000+ infantry | Wei Qing | Supreme commander | Dingxiang | Killed 19,000 Xiongnu Seized the fort of Zhaoxin |

| Guo Chang | Colonel | |||||

| Xun Zhi | ||||||

| Chang Hui | Governor of Xihe | |||||

| Sui Cheng | Governor of Yunzhong | |||||

| Li Guang | General of the vanguard | Late and rendezvouz and committed suicide | ||||

| Zhao Yiji | General of the right | Late at rendezvouz | ||||

| Gongsun Ao | General of the center | |||||

| Cao Xiang | General of the rear | |||||

| Gongsun He | General of the left | |||||

| 50,000 cavalry | Huo Qubing | Supreme commander | Dai, Yubeiping | |||

| Li Gan | Colonel | |||||

| Xu Ziwei | Colonel | Killed and captured 12,700 Xiongnu | ||||

| Lu Bode | Governor of Yubeiping | |||||

| Wei Shan | Chief commander of Bodi | Captured a Xiongnu king | ||||

| Zhao Ponu | Congpiao Marquis | |||||

| Jie | Governor of Yuyang | |||||

| Zhao Anji | Marquis of Changwu | |||||

| Fu Luji | Colonel | |||||

| Yi Jixian | ||||||

| 116 BC | Xiongnu | Raided Liang Province | ||||

| 111 BC (Autumn) | Han | 15,000 cavalry | Gongsun He | General of Fuju | Wuyuan | Failed to find Xiongnu |

| 10,000 cavalry | Zhao Ponu | General of Xiong River | Lingju | Failed to find Xiongnu | ||

| 110 BC (Winter) | Han | 180,000 cavalry | Emperor Wu of Han | Failed to find Xiongnu | ||

| 108 BC | Han | 25,000 cavalry | Zhao Ponu | Failed to find Xiongnu | ||

| 103 BC (Summer) | Han | 20,000 cavalry | Zhao Ponu | General of Junji | Killed and captured 2,000+ Xiongnu but got surrounded and surrendered | |

| 102 BC | Xiongnu | Wise king (Dugi) of the right | Raided Jiuquan and Zhangye, capturing several thousand people | |||

| 99 BC (Summer) Battle of Tian Shan | Han | 30,000 cavalry | Li Guangli | Ershi General | Shuofang | Killed and captured 10,000 Xiongnu but was surrounded on the way back and most of his forces were killed |

| Gongsun Ao | General of Yinyu | Xihe | ||||

| Lu Bode | Chief commandant of crossbowmen | Juyan | ||||

| 5,000 infantry/cavalry | Li Ling | Chief commandant of cavalry | Juyan | Killed and captured 10,000 Xiongnu but was defeated and surrendered Only 400 survived | ||

| 97 BC (Spring) | Han | 50,000 cavalry 70,000 infantry | Li Guangli | Ershi General | Shuofang | Defeated |

| 10,000 infantry | Lu Bode | Chief commandant of crossbowmen | Juyan | |||

| 30,000 infantry | Han Yue | Scouting and attacking general | Wuyuan | |||

| 10,00 cavalry 30,000 infantry | Gongsun Ao | General of Yinyu | Yanmen | Defeated | ||

| 90 BC (Spring) | Han | 9,000 cavalry (with auxiliaries) | Li Guangli | Ershi General | Wuyuan | Surrendered |

| 30,000 cavalry | Shang Qiucheng | Grand secretary | Xihe | Victory | ||

| 40,000 cavalry | Ma Tong | Marquis of Chonghe | Jiuquan | |||

| 71 BC | Han | 150,000 cavalry 50,000 Wusun | Chang Hui | Special envoy | Captured 39,000 Xiongnu and 650,000 livestock | |

| 64 BC | Xiongnu | Attacked Jiaohe and repelled by Han reinforcements | ||||

| 36 BC Battle of Zhizhi | Han | 40,000 | Gan Yanshou | Protector general | Western Regions | Victory: Killed Zhizhi Chanyu and 1,518 Xiongnu Captured 145 Xiongnu |

| Chen Tang | Deputy Colonel | Western Regions | ||||

| 44 | Han | Ma Yuan | General | Defeated | ||

| 45 | Xiongnu | Raided Changshan | ||||

| 62 | Xiongnu | Repelled | ||||

| 73 Battle of Yiwulu | Han | 12,000 cavalry | Dou Gu | Jiuquan | Pushed Xiongnu back to Barkul Nor (Lake Pulei) | |

| 74 | Han | 14,000 cavalry | Dou Gu | Captured Jushi (Turpan) | ||

| 75 | Xiongnu | Evicted the Han from the Western Regions | ||||

| 89 Battle of the Altai Mountains | Han | 8,000 cavalry 30,000 Xiongnu cavalry 8,000 Qiang auxiliaries | Dou Xian | Killed 13,000 Xiongnu 81 Xiongnu tribes surrendered Captured Yiwu | ||

| 140 | Xiongnu | Overran Tiger's Teeth encampment (near Chang'an) |

Southern wars

| Year | Aggressor | Target | Forces | Commander | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 181 BC | Nanyue | Changsha | |||

| 113 BC | Han | Nanyue | 2,000 | Han Qianqiu | Defeated |

| 112-111 BC (Autumn) Han conquest of Nanyue Han campaigns against Minyue | Han | Nanyue Minyue | 35,000 | Lu Bode Yang Pu Han Yue Wang Wenshu | Captured the capital Panyu and killed their king, Zhao Jiande The people of Minyue killed their own Zou Yushan Cangwu submitted |

| 109 BC Han conquest of Dian | Han | Dian Kingdom Yelang | Guo Chang Wei Guang | Annexed Dian, Yelang, and other tribes in Yunnan, establishing Yizhou Commandery | |

| 40 AD Trung sisters' rebellion | Trung sisters | Jiaozhi, Jiuzhen, and Rinan commanderies | Trung sisters | Rebelled | |

| 42 AD Trung sisters' rebellion | Han | Trung sisters | 8,000 regulars 12,000 militia | Ma Yuan | Victory |

| 136 AD | Chulian | Han | Several thousand | People known as the Chulian from beyond the southern frontier invaded Rinan Commandery, causing turmoil and rebellion | |

| 157 AD | Chu Dat | Han | 2,000 | Chu Dat | Chu Dat rebelled in Jiuzhen Commandery and was defeated |

| 178 AD | Liang Long | Han | Liang Long | Rebelled in Nanhai, Hepu, Jiuzhen, Jiaozhi, and Rinan commanderies | |

| 181 AD | Han | Liang Long | Zhu Juan | Victory |

Korean wars

| Year | Aggressor | Forces | Commander | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 109 BC | Han | 50,000 | Yang Pu | Defeated |

| 7,000 | Xun Zhi | Defeated | ||

| 108 BC (Spring) | Han | Xun Zhi Yang Pu | Besieged Wanggeom-seong for several months before their officials killed Ugeo of Gojoseon and surrendered Annexed and reorganized into the Four Commanderies of Han | |

| 75 BC | Goguryeo | Attacked Xuantu Commandery | ||

| 12 | Goguryeo | Repelled | ||

| 23 | Koreans | Took slaves from Lelang Commandery | ||

| 106 | Goguryeo | Took some territory from Xuantu Commandery | ||

| 132 | Han | Retook some territory in Xuantu Commandery | ||

| 149 | Goguryeo | Raided Xuantu Commandery | ||

| 169 | Han | Geng Lin | Forced Goguryeo into submission |

Western regions

| Year | Target | Forces | Commander | Title | Place of departure | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 108 BC Battle of Loulan | Loulan Kingdom | 700 | Zhao Ponu | General of the Xiong River | Subjugated Loulan Kingdom and Jushi Kingdom | |

| 104-103 BC (Autumn) War of the Heavenly Horses | Dayuan | 6,000 auxiliary cavalry 20,000+ convicted conscripts | Li Guangli | General of Sutrishna | Defeated and very few made it back alive | |

| Zhao Shicheng | Director of martial law | |||||

| Wang Hui | Expedition guide | |||||

| Li Che | Colonel | |||||

| 102-101 BC (Autumn-spring) War of the Heavenly Horses | Dayuan | 60,000 infantry/cavalry 100,000 oxen 30,000 horses 20,000+ donkeys, mules, and camels | Li Guangli | General of Sutrishna | Dunhuang | Massacred the city of Luntai Killed the king of Dayuan and captured 3,000 horses Captured a city called Yucheng (Uzgen) Reached Kangju before turning back Only 10,000 men survived |

| Wang Shencheng | Colonel | Killed | ||||

| Zhao Shicheng | Colonel | |||||

| Li Che | Colonel | |||||

| Shangguan Jie | Chief commandant of foraging | |||||

| Hu Chongge | Former grand herald | |||||

| 94 BC (Summer) | Suoju (around modern Yarkant County) | Auxiliaries from the Western Regions | Xu Xiangru | Imperial inspector | Killed King Fuluo of Suoju and captured 1,500 people | |

| 90 BC | Jushi Kingdom | 5,000 Han soldiers 30,000 auxiliaries from the states of the Western Regions | Cheng Wan | Marquis of Kailing | Subjugated Jushi Kingdom and captured its king Marks formal presence of the Han in the Western Regions | |

| 87 BC | A city near modern Islamabad | Wen Zhong | Chief commandant | Subjugated a city near modern Islamabad | ||

| 69 BC | Qiuci | 47,500 auxiliaries from the Western Regions | Chang Hui | Qiuci submitted to Han suzerainty | ||

| 68-67 BC Battle of Jushi | Jushi Kingdom | 1,500 conscripted convicts | Zheng Ji | Gentleman in attendance | Quli | Attacked Jushi Kingdom twice, succeeded the second time and started colonizing the area while the king fled to Wusun |

| Sima Xi | Colonel | Quli | ||||

| 65 BC | Suoju (near modern Yarkant County) | 15,000 auxiliaries from the Western Regions | Feng Fengshi | Marquis of Wei | Yixun | Forced the king of Suoju to commit suicide and enthroned another king |

| 16 | Yanqi | Guo Qin | The city is massacred |

Qiang

| Year | Aggressor | Forces | Commander | Place of departure | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 112 BC | Han | 20,000 cavalry | Attacked Qiang in eastern Tibet | ||

| 65 BC | Qiang | Revolted in eastern Tibet | |||

| 61 BC | Han | Zhao Chongguo | Advanced into eastern Tibet and established colonies near Qinghai Lake | ||

| 42 BC | Qiang | Revolted and defeated a force of 12,000 under Feng Fengshi | |||

| 41 BC | Han | 60,000 | Feng Fengshi | Crushed the Qiang rebellion in eastern Tibet | |

| 49 | Qiang | Retook modern Qinghai | |||

| 57 | Qiang | Dianyu | Raided Jincheng Commandery | ||

| 59 | Han | Defeated Dianyu | |||

| 108 | Qiang | Raided Liang Province | |||

| 117 | Han | Ren Shang | Defeated the Qiang | ||

| 140 | Qiang | Rebellion | |||

| 142 | Han | Put down rebellion | |||

| 167-168 | Han | Duan Jiong | Anding | Massacre of Qiang |

Wuhuan

| Year | Forces | Commander | Place of departure | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 78 BC | 20,000 | Fan Mingyou | Originally sent to aid the Wuhuan against the Xiongnu, they were too late, and attacked the Wuhuan instead |

Xianbei

| Year | Aggressor | Area invaded | Commander | Forces | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 121 | Xianbei | Qizhijian | |||

| 145 | Xianbei | Dai Commandery | |||

| 166 | Xianbei | ||||

| 168 | Xianbei | Tanshihuai | |||

| 177 | Han | Xia Yu Tian Yan | 30,000 | Defeated |

Rebellions

Notable military leaders

Western Han

Eastern Han

References

- ↑ Twitchett 2008, p. 479.

- ↑ Peers 1995, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Bielenstein 1980, p. 114.

- ↑ Crespigny 2017, p. 149.

- ↑ Twitchett 2008, p. 481-482.

- ↑ Twitchett 2008, p. 512.

- 1 2 Chang 2007, p. 179.

- ↑ Bielenstein 1980, p. 117.

- ↑ Peers 1995, p. 16.

- ↑ Crespigny 2017, p. 163.

- ↑ Twitchett 2008, p. 480.

- ↑ Cosmo 2009, p. 74.

- ↑ Cosmo 2009, p. 110-111.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 38.

- 1 2 Graff 2002, p. 36-37.

- 1 2 Chang 2007, p. 158.

- ↑ Chang 2007, p. 174-175.

- ↑ Chang 2007, p. 178.

- 1 2 Crespigny 2017, p. 159.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 75.

- ↑ Wagner 2008, p. 225.

- ↑ Peers 2006, p. 146.

- ↑ Lorge 2011, p. 68.

- ↑ Lorge 2011, p. 69.

- ↑ Lorge 2011, p. 103.

- ↑ Zhan Ma Dao (斬馬刀), retrieved 15 April 2018

- ↑ Lorge 2011, p. 69-70.

- 1 2 Crespigny 2017, p. 157.

- 1 2 Needham 1994, p. 141.

- ↑ Peers, 130–131.

- ↑ Needham 1994, p. 143.

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 22.

- ↑ Loades 2018.

- ↑ Needham 1994, p. 139.

- ↑ Needham 1994, p. 22.

- ↑ Needham 1994, p. 138.

- ↑ Needham 1994, p. 123-125.

- 1 2 Liang 2006.

- ↑ Needham 1994, p. 8.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 146.

- ↑ Chang 2007, p. 175.

- 1 2 3 4 Whiting 2002, p. 147.

- ↑ Loewe 2000, p. 123.

- ↑ Loewe 2000, p. 200.

- 1 2 3 Loewe 2000, p. 574.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 148-149.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 149.

- 1 2 Whiting 2002, p. 152.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 152-153.

- ↑ Loewe 2000, p. 174.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 154.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 154-156.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 157.

- 1 2 Whiting 2002, p. 158.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 159-158.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 160-158.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 161.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 161-162.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 163.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 164.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 165.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 166.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 168.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 169.

- ↑ Loewe 2000, p. 623.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 171.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 171-172.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 172.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 173.

- 1 2 Whiting 2002, p. 174.

- 1 2 Whiting 2002, p. 175.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 176.

- 1 2 3 4 Whiting 2002, p. 177.

- 1 2 3 Whiting 2002, p. 178.

- 1 2 Whiting 2002, p. 179.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 180.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 182.

- 1 2 3 Whiting 2002, p. 183.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 184.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 185.

- 1 2 Cosmo 2009, p. 90.

- ↑ Crespigny 2010, p. 66.

- ↑ Taylor 1983, p. 31.

- ↑ Taylor 1983, p. 32.

- 1 2 Twitchett 2008, p. 270.

- ↑ Cosmo 2009, p. 91.

- 1 2 Crespigny 2017, p. 90.

- ↑ Cosmo 2009, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 Cosmo 2009, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 Twitchett 2008, p. 421.

- ↑ Cosmo 2009, p. 103.

- ↑ Cosmo 2009, p. 108.

- 1 2 3 4 Cosmo 2009, p. 104.

- ↑ Crespigny 2017, p. 11.

- ↑ Taylor 1983, p. 48.

- ↑ Cosmo 2009, p. 106.

- ↑ Taylor 1983, p. 50.

- 1 2 Cosmo 2009, p. 107.

- ↑ Crespigny 2007, p. 257.

- ↑ Crespigny 2017, p. 13.

- 1 2 Taylor 1983, p. 53.

- ↑ Crespigny 2017, p. 401.

- ↑ Whiting 2002, p. 206.

Bibliography

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7 .

- Bielenstein, Hans (1980), The Bureaucracy of Han Times, Cambridge University Press

- Chang, Chun-shu (2007), The Rise of the Chinese Empire 1, The University of Michigan Press

- Cosmo, Nicola di (2009), Military Culture in Imperial China, Harvard University Press

- Coyet, Frederic (1975), Neglected Formosa: a translation from the Dutch of Frederic Coyett's Verwaerloosde Formosa

- Crespigny, Rafe de (2007), A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms, Brill

- Crespigny, Rafe de (2010), Imperial Warlord, Brill

- Crespigny, Rafe de (2017), Fire Over Luoyang: A History of the Later Han Dynasty, 23-220 AD, Brill

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Routledge

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War: Military practice in seventh-century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Han, Fei (2003), Han Feizi: Basic Writings, Columbia University Press

- Jackson, Peter (2005), The Mongols and the West, Pearson Education Limited

- Kurz, Johannes L. (2011), China's Southern Tang Dynasty, 937-976, Routledge

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2007), The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Loewe, Michael (2000), A BIOGRAPHICAL DICTIONARY OF THE QIN, FORMER HAN AND XIN PERIODS (221 BC - AD 24), Brill

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Loades, Mike (2018), The Crossbow, Osprey

- Lorge, Peter A. (2011), Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-87881-4

- Lorge, Peter (2015), The Reunification of China: Peace through War under the Song Dynasty, Cambridge University Press

- Mesny, William (1896), Mesny's Chinese Miscellany

- Needham, Joseph (1994), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5 Part 6, Cambridge University Press

- Peers, C.J. (1990), Ancient Chinese Armies: 1500-200BC, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1992), Medieval Chinese Armies: 1260-1520, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1995), Imperial Chinese Armies (1): 200BC-AD589, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1996), Imperial Chinese Armies (2): 590-1260AD, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (2006), Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC - AD 1840, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Peers, Chris (2013), Battles of Ancient China, Pen & Sword Military

- Perdue, Peter C. (2005), China Marches West, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Rnad, Christopher C. (2017), Military Thought in Early China, SUNY Press

- Robinson, K.G. (2004), Science and Civilization in China Volume 7 Part 2: General Conclusions and Reflections, Cambridge University Press

- Swope, Kenneth M. (2009), A Dragon's Head and a Serpent's Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592–1598, University of Oklahoma Press

- Taylor, Jay (1983), The Birth of the Vietnamese, University of California Press

- Turnbull, Stephen (2001), Siege Weapons of the Far East (1) AD 612-1300, Osprey Publishing

- Turnbull, Stephen (2002), Siege Weapons of the Far East (2) AD 960-1644, Osprey Publishing

- Twitchett, Denis (2008), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, Cambridge University Press

- Whiting, Marvin C. (2002), Imperial Chinese Military History, Writers Club Press

- Wood, W. W. (1830), Sketches of China

- Wagner, Donald B. (2008), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5-11: Ferrous Metallurgy, Cambridge University Press

- Wright, David (2005), From War to Diplomatic Parity in Eleventh Century China, Brill

- Late Imperial Chinese Armies: 1520-1840 C.J. Peers, Illustrated by Christa Hook, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 1-85532-655-8