Alert, Nunavut

| Alert | |

|---|---|

| Weather station and Canadian Forces Station | |

View of the main CFS Alert complex from the south, May 2016 | |

| Motto(s): Inuit Nunangata Ungata (Beyond the Inuit Land) | |

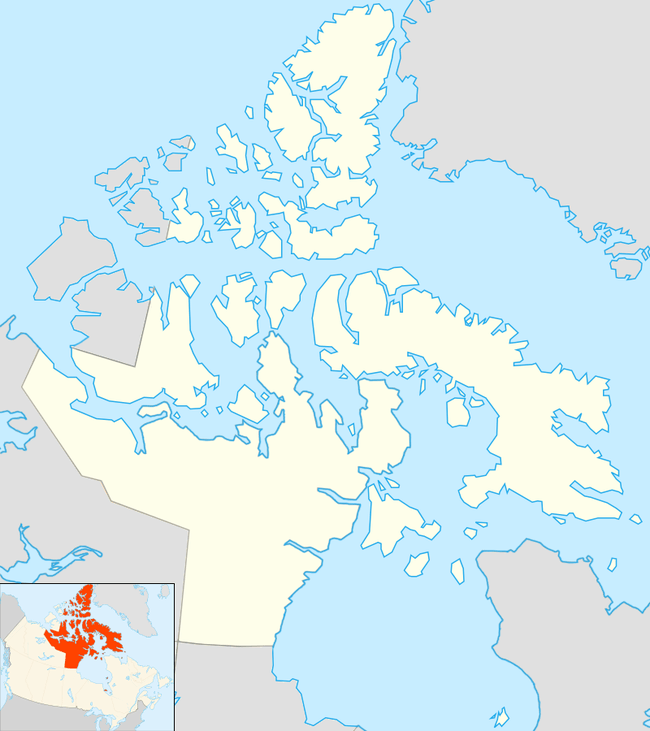

Alert  Alert | |

| Coordinates: 82°30′6″N 62°20′53″W / 82.50167°N 62.34806°WCoordinates: 82°30′6″N 62°20′53″W / 82.50167°N 62.34806°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Territory | Nunavut |

| Region | Qikiqtaaluk Region |

| Established | April 9, 1950 |

| Elevation[1] | 100 ft (30 m) |

| Population (2016)[2] | |

| • Total | 62 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| GNBC Code | OAAQK[3] |

Alert, in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada, is the northernmost permanently inhabited place in the world,[4] at latitude 82°30'05" north, 817 kilometres (508 mi) from the North Pole.[5] The entire population of the census subdivision Baffin, Unorganized is located here. (Baffin Region is the Statistics Canada name for Qikiqtaaluk.) As of the 2016 census the population was reported as 62, an increase of 57 over the 2011 census.[2] It takes its name from HMS Alert, which wintered 10 km (6.2 mi) east of the present station, off what is now Cape Sheridan, in 1875–1876.

Alert has many temporary inhabitants as it hosts a military signals intelligence radio receiving facility at Canadian Forces Station Alert (CFS Alert), as well as a co-located Environment Canada weather station, a Global Atmosphere Watch (GAW) atmosphere monitoring observatory, and the Alert Airport.

Early history

Alert is named after HMS Alert, a British ship that wintered about 10 km (6.2 mi) away in 1875–76.[6] The ship's captain, George Nares, and his crew were the first recorded Europeans to reach the northern end of Ellesmere Island. Over the following decades, several other expeditions passed through the area, most notably Robert Peary during his successful journey to the north pole in 1909.

Weather station

Shortly after the end of World War II, Charles J. Hubbard of the United States Weather Bureau began to rouse interest in the United States and Canada for the establishment of a network of Arctic stations. His plan, in broad perspective, envisaged the establishment of two main stations, one in Greenland and the other within the Archipelago, which could be reached by sea supply. These main stations would then serve as advance bases from which a number of smaller stations would be established by air. The immediate plans contemplated the establishment of weather stations only, but it was felt that a system of weather stations would also provide a nucleus of transportation, communications and settlements which would greatly aid programs of research in many other fields of science. It was recognized that ultimate action would depend on international co-operation since the land masses involved were under Canadian and Danish control.

Following negotiations between the American and Canadian governments a group of five weather stations were established, known as the Joint Arctic Weather Stations (JAWS). On the Canadian side, the stations were to be operated by the Department of Transport. The locations for each station were surveyed in 1946, and a cache of supplies was dropped in Alert in 1948 by USS Edisto. Alert was the last of the five to be settled when the first twelve personnel (eight permanent staff and four to assist with construction) arrived on April 9, 1950.[7] Construction began immediately, with the first priority being the creation of an ice runway on Alert Inlet before work began on the permanent all-season runway located on Cape Belknap. Until its completion, supplies were parachuted in.

On July 30, 1950, nine crew members of a Royal Canadian Air Force Lancaster died in a crash while making an airdrop of supplies to the station.

The last American personnel were withdrawn on October 31, 1970,[8] and the following year operation of the weather station was transferred to the newly created Department of the Environment, with the Department of Transport retaining control of airfield operations for several more years.

In April 1971 a party of federal and Northwest Territories (NWT) government officials arrived in Alert in an attempt to reach the North Pole. Alert had been the embarkation point for many North Pole expeditions that relied on weather information supplied by the weather station there. The 1971 expedition was led by NWT Commissioner, Stuart Hodgson, and included in his party were representatives of the Prime Minister's office, the Canadian Armed Forces, the federal Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development as well as a large media group including Pat Carney of Gemini Productions, Ed Ogle of Time magazine, Val Wake of CBC News and a television crew from California. While waiting in Alert for a weather window to fly into the Pole, the party's television crew spent a lot of time filming at the weather station. The military was unhappy about the film crew working on the station but the weather station was seen as being a sort of no-man's land. The Commissioner's party made two attempts to reach the Pole and failed. Some of the incidents surrounding this event are recounted in Val Wake's memoir My Voyage around Spray with Apologies to Captain Joshua Slocum.[9]

The remaining buildings which comprised the original weather station, having fallen into a state of disrepair, were burned in the summer of 1996, leaving only the hydrogen shed and a wooden outhouse. The weather station and observatory offices were moved to Polaris Hall.

Dr. Neil Trivett Global Atmosphere Watch Observatory

In 1975, technicians employed by the weather station began collecting flask samples for a greenhouse gas monitoring program. In 1980, this grew to include the weekly collection of filter-based aerosol samples for the Canadian Arctic Aerosol Sampling Network (CAASN).[10]

By 1984, the number of ongoing monitoring programs and the amount of experimental research had outgrown the abilities of the weather station to maintain, and plans were made for the construction of a permanent observatory. This observatory, located 400 metres (440 yd) southwest of Lancaster Hall (more commonly known as the far transmitter building), was opened August 29, 1986. Originally known as the Alert Background Air Pollution Monitoring Network (BAPMoN) Observatory, it was subsequently renamed the Dr. Neil Trivett Global Atmosphere Watch Observatory in honour of the Environment Canada researcher who provided the impetus for its construction.[11]

The observatory employs two technicians, who reside at CFS Alert: an operator and an assistant operator (normally a university co-op student).

Canadian Forces Station Alert

Since the beginning of the JAWS project, the Canadian military had been interested in the establishment at Alert for several reasons: the JAWS facility extended Canadian sovereignty over a large uninhabited area which Canada claimed as its sovereign territory, and furthermore, its proximity to the Soviet Union made it of strategic importance. In fact, Alert is closer to Moscow (c. 2,500 mi (4,000 km)) than it is to Ottawa (c. 2,580 mi (4,150 km)). Thus, the possibility of utilizing the site for the purpose of intercepting radio signals was deemed to warrant a military presence.

In 1956, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), which was expanding its presence throughout the high Arctic with the construction of the Distant Early Warning Line radar network, established a building uphill from the DOT's JAWS station to house "High Arctic Long Range Communications Research", or signals intelligence operations.

In 1957, Alert Wireless Station was conceived as an intercept facility to be jointly staffed by personnel from the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and the RCAF. Five additional buildings were constructed: a mess, three barracks/accommodations buildings, and a power house and vehicle maintenance building, in addition to the existing operations building, built in 1956. The operations building housed the radio intercept and cryptographic equipment. On September 1, 1958 control of the station was transferred from the Air Force to the Army and it officially began operations.

The following decade saw a dramatic expansion of the station with a correspondingly greater number of personnel stationed there. The February 1, 1968 unification of the RCN, RCAF and Canadian Army to form the Canadian Armed Forces saw Alert Wireless Station change its name to Canadian Forces Station Alert (CFS Alert). Its personnel were no longer drawn from only the Air Force or Navy, but primarily from the Canadian Forces Communications Command.

At its peak, CFS Alert had upwards of 215 personnel posted at any one time. The station became a key asset in the global ECHELON network of the US-UK-CAN-AUS-NZ intelligence sharing alliance, with Alert being privy to many secret Soviet communications regarding land-based and sea-based ICBM test launches and many operational military deployments.

The first military women to serve in Alert arrived in 1980 as part of the Canadian Forces' Women In Non-Traditional Roles study. After its completion in 1983, women were fully authorized to serve in all roles.[12] The first female commanding officer was Maj. Cathy Cowan, who took command in January 1996. The first female Station Warrant Officer (SWO), MWO Renee Hansen, was appointed in December 2017.[13]

Budget cuts to the Department of National Defence and Canadian Forces in 1994, and modernization of communications equipment, saw CFS Alert downsized to approximately 74 personnel by 1997–1998 when most radio-intercept operations were remotely controlled by personnel at CFS Leitrim. Remaining personnel are responsible for airfield operations, construction/engineering, food service, and logistical/administrative support. Only six personnel are now responsible for actual operations, and control of the facility was passed to DND's Information Management Group following the disbanding of CF Communications Command with force restructuring and cutbacks in the mid-1990s. Several of these personnel are likely also attached to DND's Communications Security Establishment.

With Canada's commitment to the global war on terrorism following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in New York City and Washington, D.C., CFS Alert has received renewed and increased funding to expand its SIGINT capabilities. On April 1, 2009, the RCAF officially took responsibility for CFS Alert from Canadian Forces Information Operations Group (CFIOG).

Civilian contractor

As of April 13, 2006 the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation was reporting that the heating costs for the station had risen, as a consequence of which the military proposed to cut back on support trade positions by using private contractors.[14] By 2008, maintenance operations on station—including food and housekeeping services, vehicle maintenance, powerplant operation, and heating, electrical, and plumbing—had been transferred to a civilian contractor. The contract was initially awarded to Canadian Base Operators (CBO), a subsidiary of Black & McDonald. In 2012, the contract was won by Nasittuq, a subsidiary of ATCO.

Notable events and visitors

- In August 1975 Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau and his 3-year-old son Justin Trudeau visited the station and nearby Ward Hunt Island.[15]

- In early April 2006 the Roly McLenahan Torch that was used to light the flame at Whitehorse, Yukon for the Canada Winter Games passed through Alert.[16] While the Canada Games torch was supposed to pass over the North Pole, bad weather prevented a Canadian military Twin Otter from making the trip. The torch did not travel outside Alert that weekend (April 9–12).

- In August 2006 then-Prime Minister, Stephen Harper, made a visit to Alert as part of his campaign to promote Canadian sovereignty in the north.

- On November 8, 2009, the 2010 Winter Olympics torch relay arrived at Alert via airplane from Churchill, Manitoba, reaching its most northerly point on land.[17] The next day it travelled to Iqaluit.

- On January 19 and 20, 2015, Governor General David Johnston flew into Alert on a C-17 Globemaster transport from CFB Trenton.[18] He toured Alert, received an overview of its operations, met with civilian and military personnel and presided over a change-of-command.[19]

Aircraft crashes

Since Alert has not been regularly accessible by icebreakers due to heavy ice conditions in the Lincoln Sea, resupply is provided by Royal Canadian Air Force transport aircraft which land at the adjacent Alert Airport. Difficult conditions at such a remote northern location have resulted in several incidents, two of which have involved fatalities:

- On July 31, 1950, around 1700 hours GMT, a RCAF Lancaster 965 from 405 Squadron Greenwood crashed during the establishment of the JAWS weather station when the parachute for resupplies being airdropped became entangled on the tail of the aircraft. The nine crew members were killed. An attempt was made to recover their bodies; an RCAF Canso flying boat was dispatched and landed in Dumbell Bay on August 7. The bodies of the Canadian crew were brought aboard in wooden coffins made from packing crates — the family of Colonel C.J. Hubbard of the United States Weather Bureau requested his remains be buried at Alert[20] — but the combination of the extra weight and a tail wind resulted in an aborted takeoff. The Canso struck ground at the narrow point of Dumbell Bay, damaging the tail section and rendering it useless. Following this, it was decided to bury the crew's remains west of the airstrip, and a military funeral was held the same day. The arrival of the United States Coast Guard icebreaker Eastwind allowed repairs to be made to the Canso.[21] The wreckage of the Lancaster is still visible 500 m (1,600 ft) southwest of the CE building.

- On October 11, 1952, an American Military Air Transport Service Douglas C-54 Skymaster crashed on landing at Alert, while carrying a load of aviation fuel. The four crew members survived the crash; however, the aircraft was completely destroyed. The wreckage was pushed to the south side of the runway, where it remains today. Because of the high visibility of the wreckage due to its location at the runway, it is often mistaken for the RCAF Lancaster.[21]

- On October 30, 1991, a Lockheed C-130 Hercules, part of Operation Boxtop, crashed about 20 km (12 mi) from the airfield, killing 4 of the 18 passengers and crew on impact, while pilot John Couch died of exposure following the crash. Couch was conducting a visual approach and descended into a hill due to a mistake regarding the plane's true location.[22] A blizzard and the local terrain hampered subsequent rescue efforts by personnel from CFS Alert, USAF personnel from Thule Air Base 700 km (430 mi) south, and 435 Transport and Rescue Squadron from CFB Winnipeg and 440 Transport and Rescue Squadron, from CFB Namao outside Edmonton, both squadrons are part of 17 Wing Winnipeg, and 424 Squadron from CFB Trenton, Ontario, 413 Transport and Rescue Squadron from CFB Greenwood, Nova Scotia. The crash investigation recommended all C-130s be retrofitted with ground proximity detectors. The crash and rescue efforts were the basis of the film Ordeal in the Arctic (1993).

Demographics

| Historical populations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1991 | 246 | — |

| 1996 | 270 | +9.8% |

| 2001 | 5 | −98.1% |

| 2006 | 5 | +0.0% |

| 2011 | 5 | +0.0% |

| 2016 | 62 | +1140.0% |

While Alert has no permanent residents, it has been permanently inhabited since April 1950. This population, while initially small, grew to upwards of 250 in the 1970s and 80s, before being reduced in the 1990s. Its current population ranges from a winter minimum of 65 to a summer maximum of 110, plus a variety of short-term visitors which can swell the total to 150 or more.

Geography

Alert is located 12 km (7.5 mi) west of Cape Sheridan, the northeastern tip of Ellesmere Island, on the shore of the ice-covered Lincoln Sea. Alert lies just 817 km (508 mi) from the North Pole; the nearest Canadian city is Iqaluit, the capital of the territory of Nunavut, 2,092 km (1,300 mi) away.

The settlement is surrounded by rugged hills and valleys. The shore is composed primarily of slate and shale. The sea is covered with sea ice for most of the year but the ice pack does move out in the summer months, leaving open water. Evaporation rates are also very low, as average monthly temperatures are above freezing only in July and August.

Other places on Ellesmere Island are the weather station at Eureka (480 km (300 mi)) and the Inuit community of Grise Fiord, 800 km (500 mi), to the southwest and south, respectively. Siorapaluk (540 km (340 mi) to the south) is the nearest populated place in Greenland.

Climate

Alert has a polar climate, technically a tundra climate with characteristics of an ice cap climate. There is complete snow cover for at least 10 months of the year on average and snow from one year persists into the next year in protected areas, but enough melts to prevent glaciation. The warmest month, July, has an average temperature of 3.4 °C (38.1 °F), with only July and August averaging above freezing, and those are also the months where well over 90% of the rainfall occurs. Alert is also very dry, the fourth-driest locality in Nunavut, averaging only 158.3 mm (6.23 in) of precipitation per year. Most of this occurs during the months of July, August and September, mostly in the form of snow. On average Alert sees 17.4 mm (0.69 in) of rain, the least of any place in Nunavut, between June and September. Alert sees very little snowfall during the rest of the year. September is usually the month with the heaviest snowfall. February is the coldest month of the year with a mean temperature of −33.2 °C (−27.8 °F). The yearly mean, −17.7 °C (0.1 °F), is the second-coldest in Nunavut after Eureka. Snowfall can occur during any month of the year, although there might be about 28 frost-free days in an average summer.[23]

Being far north of the Arctic Circle, Alert experiences polar night from October 14 to February 28, and midnight sun from April 7 to September 4. There are two relatively short periods of twilight from about February 13 to March 22 and the second from September 19 to October 22. The civil polar night lasts from October 29 to February 11.[24]

Nautical polar night — where 24 hours are in effect completely dark with only a marginal astronomical twilight — occurs from November 19 to January 22.[25]

| Climate data for Alert Airport, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1950–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 0.0 | 0.0 | −2.4 | −1.1 | 6.6 | 18.1 | 19.4 | 23.8 | 8.4 | 3.9 | −1.1 | 1.4 | 23.8 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 0.0 (32) |

1.1 (34) |

−2.2 (28) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

10.0 (50) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.0 (68) |

19.5 (67.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

5.3 (41.5) |

0.6 (33.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

20.0 (68) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −28.6 (−19.5) |

−29.4 (−20.9) |

−28.4 (−19.1) |

−20.4 (−4.7) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.1 (43) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−15.3 (4.5) |

−22.3 (−8.1) |

−25.6 (−14.1) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −32.2 (−26) |

−33.2 (−27.8) |

−32.4 (−26.3) |

−24.3 (−11.7) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

3.4 (38.1) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−18.9 (−2) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−29.4 (−20.9) |

−17.7 (0.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −35.8 (−32.4) |

−37.0 (−34.6) |

−36.3 (−33.3) |

−28.1 (−18.6) |

−14.5 (5.9) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−22.4 (−8.3) |

−29.6 (−21.3) |

−33.1 (−27.6) |

−21.0 (−5.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −48.9 (−56) |

−50.0 (−58) |

−49.4 (−56.9) |

−45.6 (−50.1) |

−29.0 (−20.2) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−15.0 (5) |

−28.2 (−18.8) |

−39.4 (−38.9) |

−43.5 (−46.3) |

−46.1 (−51) |

−50.0 (−58) |

| Record low wind chill | −64.7 | −60.5 | −59.5 | −56.8 | −40.8 | −21.1 | −10.3 | −19.2 | −36.9 | −49.4 | −53.7 | −57.3 | −64.7 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 7.2 (0.283) |

7.0 (0.276) |

7.5 (0.295) |

10.6 (0.417) |

11.6 (0.457) |

12.0 (0.472) |

31.8 (1.252) |

17.9 (0.705) |

22.3 (0.878) |

13.4 (0.528) |

10.4 (0.409) |

6.8 (0.268) |

158.3 (6.232) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.8 (0.031) |

13.0 (0.512) |

3.5 (0.138) |

0.1 (0.004) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

17.4 (0.685) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 9.0 (3.54) |

8.1 (3.19) |

8.7 (3.43) |

12.6 (4.96) |

18.0 (7.09) |

13.5 (5.31) |

20.0 (7.87) |

16.9 (6.65) |

33.1 (13.03) |

20.2 (7.95) |

15.2 (5.98) |

9.3 (3.66) |

184.6 (72.68) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 9.0 | 7.7 | 7.3 | 8.5 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 10.9 | 9.2 | 10.1 | 10.5 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 106.1 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 6.9 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 9.1 | 8.6 | 8.3 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 7.4 | 11.3 | 12.2 | 9.7 | 9.9 | 108.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66.8 | 66.6 | 66.9 | 71.1 | 81.5 | 87.1 | 85.1 | 86.1 | 84.6 | 75.7 | 70.3 | 67.2 | 75.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 0.0 | 0.0 | 110.4 | 323.6 | 428.6 | 333.0 | 321.6 | 269.1 | 111.4 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1,901.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | N/A | N/A | 33.1 | 46.8 | 57.6 | 46.3 | 43.2 | 36.2 | 21.9 | 4.1 | N/A | N/A | 36.1 |

| Source: Environment Canada[23][26][27][28] | |||||||||||||

See also

- Nord, Greenland - the second-northernmost permanent settlement in the world

- Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard, the northernmost settlement/town in the world with a permanent population of civilians

- Dr. Neil Trivett Global Atmosphere Watch Observatory, an atmospheric monitoring station in Alert operated by Environment and Climate Change Canada

- Puerto Williams, Chile; the southernmost settlement on Earth

References

- ↑ Canada Flight Supplement. Effective 0901Z 19 July 2018 to 0901Z 13 September 2018.

- 1 2 "2016 Community Profiles Csmbridg Bay". Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Alert". Natural Resources Canada. October 6, 2016.

- ↑ Reynolds, Lindor (August 31, 2000). "Life is cold and hard and desolate at Alert, Nunavut". Guelph Mercury. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2010. ("Twice a year, the military resupply Alert, the world's northernmost settlement.")

- ↑ "Alert, Nunavut". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on August 9, 2008. Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ↑ A History of the Canadian Coast Guard and Marine Services Archived September 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Johnson, Jr., J. Peter (January 1, 1990). "The Establishment of Alert, N.W.T., Canada". ARCTIC. 43 (1). doi:10.14430/arctic1587.

- ↑ "High Arctic Weather Stations". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ↑ My Voyage Around Spray Val Wake website

- ↑ "Canadian Arctic Aerosol Chemistry Program (CAACP)". Environment and Climate Change Canada. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ↑ Whitnell, Tim (August 20, 2006). "Scientist honoured for work". The Hamilton Spectator. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ↑ "Canadian Forces Station Alert | 8 Wing | Royal Canadian Air Force". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-11-06.

- ↑ Brunet, Julie. "CFS Alert welcomes first female station warrant officer – The Maple Leaf". The Maple Leaf. Government of Canada. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ↑ "Costly fuel prompts cuts at northern military station". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. April 13, 2006. Retrieved August 9, 2008. article mirror

- ↑ "Discovery recalls Justin Trudeau's 1st visit to High Arctic — as a 3-year-old". CBC News.

- ↑ "Vancouver 2010 Olympic Torch Relay coming to Nunavut". CNW. November 21, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Olympic Torch Relay heads to Vancouver". The Big Picture. boston.com. December 4, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ↑ Allemang, John; Cowan, Tonia (January 23, 2015). "Governor-General Johnston discusses Alert, Canada's northern 'anchor point'". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ "Governor General and Commander-in-Chief Visits Canadian Forces Station Alert". News Release on Governor-General web site. January 19, 2015.

- ↑ Pigott, Peter (2011). From Far and Wide: A Complete History of Canada's Arctic Sovereignty. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-55488-987-7.

- 1 2 Gray, David R. (2004). Alert: Beyond the Inuit Lands. Ottawa: Borealis Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 1-896133-01-0.

- ↑ Lee, Robert Mason (1993). Death and Deliverance: The True Story of an Airplane Crash at the North Pole. Golden CO: Fulcrum Publishing. ISBN 978-1555911409.

- 1 2 "Alert A" (CSV (4222 KB)). Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Climate ID: 2400300. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ↑ Sunrise/Sunset/Sun Angle Calculator

- ↑ "Time and Date.com - Alert, Nunavut, Canada". Time and Date.com. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Daily Data Report for October 2006". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Daily Data Report for June 2009". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Daily Data Report for May 2012". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

Further reading

- Bottenheim, Jan W, Hacene Boudries, Peter C Brickell, and Elliot Atlas. 2002. "Alkenes in the Arctic Boundary Layer at Alert, Nunavut, Canada". Atmospheric Environment. 36, no. 15: 2585.

- Diggle, Dennis A., and David G. Otto. Drilling of an Arctic Protected Cable Route, Alert, Ellesmere Island, N.W.T. [Victoria, B.C.]: Defence Research Establishment Pacific, Research and Development Branch, Dept. of National Defence, 1994.

- Morrison, R. I. G., N. C. Davidson, and Theunis Piersma. Daily Energy Expenditure and Water Turnover of Shorebirds at Alert, Ellesmere Island, N.W.T. Progress notes (Canadian Wildlife Service), no. 211. Ottawa: Canadian Wildlife Service, 1997. ISBN 0-662-25795-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alert, Nunavut. |