Grise Fiord

| Grise Fiord ᐊᐅᔪᐃᑦᑐᖅ Aujuittuq | |

|---|---|

| Hamlet | |

| |

Grise Fiord  Grise Fiord | |

| Coordinates: 76°25′03″N 082°53′38″W / 76.41750°N 82.89389°WCoordinates: 76°25′03″N 082°53′38″W / 76.41750°N 82.89389°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Territory | Nunavut |

| Region | Qikiqtaaluk Region |

| Electoral district | Quttiktuq |

| Settled | 1953 |

| Government[1]>[2] | |

| • Mayor | Meeka Kiguktak |

| • MLA | David Akeeagok |

| Area[3] | |

| • Total | 332.70 km2 (128.46 sq mi) |

| Elevation[4] | 41 m (135 ft) |

| Population (2016)[3] | |

| • Total | 129 |

| • Density | 0.4/km2 (1/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Canadian Postal code | X0A 0J0 |

| Area code(s) | 867, Exchange: 980 |

| Website | www.grisefiord.ca |

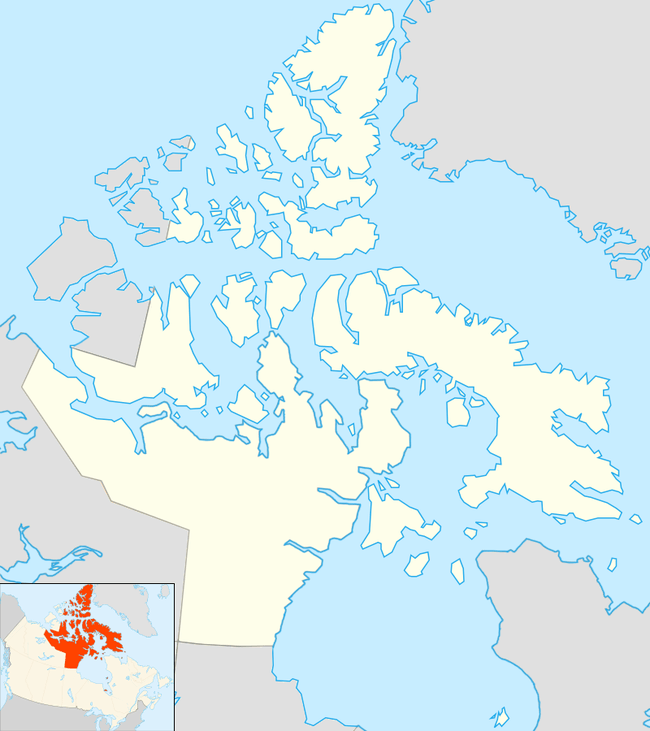

Grise Fiord, (Inuktitut: Aujuittuq, "place that never thaws"; Inuktitut syllabics: ᐊᐅᔪᐃᑦᑐᖅ) is an Inuit hamlet in the Qikiqtaaluk Region in the territory of Nunavut, Canada. Despite its low population (129 residents as of the Canada 2016 Census),[3] it is the largest community on Ellesmere Island. It is also one of the coldest inhabited places in the world, with an average yearly temperature of −16.5 °C (2.3 °F).

Geography

Located at the southern tip of Ellesmere Island, Grise Fiord is one of three permanent settlements on the island. Grise Fiord lies 1,160 km (720 mi) north of the Arctic Circle.

Grise Fiord is the northernmost civilian settlement in Canada,[5] but Environment Canada has a permanent weather station at Eureka, and at Alert there is a permanent Canadian Forces Base (CFS Alert) and weather station, that lie further north on the island.

Grise Fiord cradles the Arctic Cordillera mountain range.

Naming

Grise Fiord means "pig inlet" in Norwegian and was named by Otto Sverdrup from Norway during an expedition around 1900. He thought the walrus in the area sounded like pigs. Grise Fiord's Inuktitut name is Aujuittuq which means "place that never thaws."

Living conditions

The population of Grise Fiord is declining, and consists of around 129 permanent residents, a decrease of 0.8% (1 person) from the 2011 census.[3] The houses are wooden and built on platforms to cope with the freezing and thawing of the permafrost. Hunting is still an important part of the lifestyle of the mostly Inuit population. Quota systems allow the villagers to supply many of their needs from populations of seals, walruses, narwhal and beluga whales, polar bears and muskox. Ecotourism is developing as people come to see the northern wildlife found on Ellesmere and surrounding islands.[6]

Transportation

There are no connecting roads on Ellesmere Island, so Grise Fiord is connected to the rest of the world by a small airstrip (Grise Fiord Airport) 1,670 feet (510 m) in length. It is one of the most difficult approaches for aircraft, and it is cautioned that only very experienced pilots and DHC-6 Twin Otter aircraft attempt the approach. For local travel needs, the villagers use all-terrain vehicles in the summer and snowmobiles in the winter. But during the winter months travel is limited to the town site and a small patch of land to the east called Nuvuk, due to mountains and ice fields that cut the town off from the rest of the island. Small boats are used in summer to reach hunting grounds, or hunting sea mammals on the ocean. Once a year large ships (sealift) arrive with supplies and fuel.

Economy, development, and sustainability

There is a local co-operative which is the main place to purchase supplies. There are local guide and outfitting operations which are an important source of income for many families. Carving and traditional crafts and clothing are also important sources of income. The economy is a subsistence-based one due to the extreme location. Grise Fiord is the most isolated true community anywhere on the planet. Because of falling rock/avalanche potential from mountains, there is no room for growth.

Broadband communications

The community has been served by the Qiniq network since 2005. Qiniq is a fixed wireless service to homes and businesses, connecting to the outside world via a satellite backbone. The Qiniq network is designed and operated by SSI Micro. In 2017, the network was upgraded to 4G LTE technology, and 2G-GSM for mobile voice.

Crime and safety

A Simon Fraser University study of Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) activity in the Baffin Region states that Grise Fiord had the lowest rate of criminal offences of all communities looked at in 1992,[7] and cites a 1994 Statistics Canada survey that gives the highest perception of personal safety.[8]

History

Settlement

The settlement (and Resolute) was created by the Canadian government in 1953, partly to assert sovereignty in the High Arctic during the Cold War. Eight Inuit families from Inukjuak, Quebec (on the Ungava Peninsula) were relocated after being promised homes and game to hunt, but the relocated people discovered no buildings and very little familiar wildlife.[10] They were told that they would be returned home after a year if they wished, but this offer was later withdrawn as it would damage Canada's claims to sovereignty in the area and the Inuit were forced to stay. Eventually, the Inuit learned the local beluga whale migration routes and were able to survive in the area, hunting over a range of 18,000 km2 (6,900 sq mi) each year.[11]

In 1993, the Canadian government held hearings to investigate the relocation program. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples issued a report entitled The High Arctic Relocation: A Report on the 1953–55 Relocation, recommending a settlement.[12] The government paid $10 million CAD to the survivors and their families,[13] and gave a formal apology in 2010.[14]

In 2009, Looty Pijamini was commissioned by the Canadian Government to design a monument in memory of the relocation.[15] Depicting a woman with a young boy and a husky, the monument was unveiled by John Duncan, Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians, on September 10, 2010.[16][17]

Telephone network

In 1970, Bell Canada established what was then the world's most northerly telephone exchange (operated since 1992 by Northwestel). It is in the 867 area code (formerly 819, before October 1997) with its only exchange code of 980.

See also

- List of municipalities in Nunavut

- Florin Fodor, a Romanian who was arrested trying to enter Canada via Grise Fiord in 2006.

References

- ↑ "NunatsiaqOnline 2013-12-03: NEWS: Nunavummiut vie for council positions in upcoming hamlet elections".

- ↑ Results for the constituency of Quttiktuq Archived 2013-11-13 at the Wayback Machine. at Elections Nunavut

- 1 2 3 4 "Census Profile, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- ↑ Elevation at airport. Canada Flight Supplement. Effective 0901Z 19 July 2018 to 0901Z 13 September 2018.

- ↑ "Grise Fiord fire hall catches fire". CBC News. October 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Grise Fiord: Wildlife".

- ↑ Curt Taylor Griffiths, Gregory Saville, Darryl S. Wood, and Evelyn Zellerer. POLICING THE BAFFIN REGION, N.W.T.: Findings From the Eastern Arctic Crime and Justice Study, 1995

- ↑ "Aboriginal Peoples Survey", Statistics Canada, 1994, cited on p17 of Curt Taylor Griffiths, Gregory Saville, Darryl S. Wood, and Evelyn Zellerer, POLICING THE BAFFIN REGION, N.W.T.: Findings From the Eastern Arctic Crime and Justice Study

- ↑ Grise Fiord's only church a 'total loss' after late night fire

- ↑ "Grise Fiord: History". Grisefiord.ca. Archived from the original on 2008-12-28. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ↑ McGrath, Melanie. The Long Exile: A Tale of Inuit Betrayal and Survival in the High Arctic. Alfred A. Knopf, 2006 (268 pages) Hardcover: ISBN 0-00-715796-7 Paperback: ISBN 0-00-715797-5

- ↑ The High Arctic Relocation: A Report on the 1953–55 Relocation by René Dussault and George Erasmus, produced by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, published by Canadian Government Publishing, 1994 (190 pages)"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-10-01. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ↑ Royte, Elizabeth (2007-04-08). "Trail of Tears". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Apology for the Inuit High Arctic relocation". www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Carvers chosen for Arctic monuments" Archived 2012-03-25 at the Wayback Machine., Northern News Services. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ↑ "Minister Duncan Attends Unveiling of Inuit Relocation Monuments" Archived 2010-10-09 at the Wayback Machine., Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ↑ Gabriel Zarate, "For Grise Fiord’s exiles, an apology that came too late", Nunatsiaq Online. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grise Fiord. |