Ajuran Sultanate

| Ajuran Sultanate Dawladdii Ajuuraan الدولة الأجورانيون | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early 13th century–Late 17th century | |||||||||

_flag_according_to_1576_Portuguese_map.svg.png) Flag | |||||||||

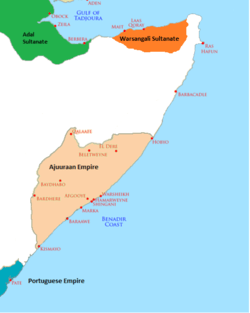

The Ajuuraan Sultanate in the 15th century | |||||||||

| Capital | Mogadishu | ||||||||

| Common languages | Somali · Arabic | ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Sultan, Imam | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | Early 13th century | ||||||||

| 1538–57 | |||||||||

| 1580–89 | |||||||||

| Mid-17th century | |||||||||

• Decline | Late 17th century | ||||||||

| Currency | Ajuran • Mogadishan | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||

The Ajuran Sultanate (Somali: Dawladdii Ajuuraan, Arabic: الدولة الأجورانيون), also spelled Ajuuraan Sultanate,[1] and often simply as Ajuran,[2] was a Somali empire in the medieval times that dominated the Indian Ocean trade. They belonged to the Somali Muslim sultanate [3][4][5] that ruled over large parts of the Horn of Africa in the Middle Ages. Through a strong centralized administration and an aggressive military stance towards invaders, the Ajuran Sultanate successfully resisted an Oromo invasion from the west and a Portuguese incursion from the east during the Gaal Madow and the Ajuran-Portuguese wars. Trading routes dating from the ancient and early medieval periods of Somali maritime enterprise were strengthened or re-established, and foreign trade and commerce in the coastal provinces flourished with ships sailing to and coming from many kingdoms and empires in East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Europe, Middle East, North Africa and East Africa.[6]

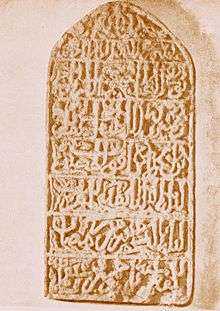

The Kingdom left an extensive architectural legacy, being one of the major medieval Somali powers engaged in sophisticated and advanced castle, fortress and various of architectures. Many of the ruined fortifications dotting the landscapes of southern Somalia today are attributed to the Ajuran Sultanate's engineers,[7] including a number of the pillar tomb fields, necropolises and ruined cities built in that era. During the Ajuran period, many regions and people in the southern part of the Horn of Africa converted to Islam because of the theocratic nature of the government.[8] The royal family, the House of Garen, expanded its territories and established its hegemonic rule through a skillful combination of warfare, trade linkages and alliances.[9]

In the 13th century AD, the Ajuran Empire was the only hydraulic empire in Africa. As an hydraulic empire, the Ajuran monopolized the water resources of the Shebelle and Jubba rivers. Through hydraulic engineering, it also constructed many of the limestone wells and cisterns of the state that are still operative and in use today. The rulers developed new systems for agriculture and taxation, which continued to be used in parts of the Horn of Africa as late as the 19th century.[1] The tyrannical rule of the later Ajuran rulers caused multiple rebellions to break out in the sultanate, and at the end of the 17th century, the Ajuran state disintegrated into several successor kingdoms and states, the most prominent being the Geledi Sultanate.[10]

Location

The Ajuran Sultanate's sphere of influence in the Horn of Africa was the largest in the region. The sultanate covered much of southern Somalia and eastern Ethiopia,[6][11] with its domain extending from Hobyo in the north, to Qelafo in the west, to Kismayo in the south.[12][13]

Origins and the House of Garen

| The House of Gareen Known members |

|---|

|

The House of Garen was the ruling hereditary dynasty of the Ajuran Sultanate.[14][9] Its origin lies in the 9th century during the Mogadishu Sultanate which it succeed from during the early 13th century and began to rule southern and central Somalia and eastern Ethiopia. With the migration of Somalis from the northern half of the Horn region to the southern half, new cultural and religious orders were introduced that influenced the administrative structure of the dynasty, a system of governance which began to evolve into an Islamic government. Through their genealogical Baraka, which came from the saint Balad (who was known to have come from outside the Garen Kingdom),[15] the Garen rulers claimed supremacy and religious legitimacy over other groups in the Horn of Africa. Balad's ancestors are said to have come from the historical northern region of Berbera.

Administration

The Ajuran nobility used many of the typical Somali aristocratic and court titles, with the Garen rulers styled Imam. These leaders were the sultanate's highest authority, and counted multiple Sultans, Emirs, and Kings as clients or vassals. The Garen rulers also had seasonal palaces in Mareeg, Qelafo and Merca, which they would periodically visit practice primae noctis.[9] However, Mogadishu was the official headquarters of the Garen Dynasty and served as the capital for the Ajuran Kingdom. The state religion was Islam, and thus law was based on Sharia.

- Imam– Head of the State[15]

- Emir – Commander of the armed forces and navy

- Na'ibs – Viceroys[15]

- Wazirs' – Tax and revenue collectors

- Qadis'– Chief Judges

Nomadic citizens and farming communities

Through their control of the region's wells, the Garen rulers effectively held a monopoly over their nomadic subjects as they were the only hydraulic empire in Africa during their reign. Large wells made out of limestone were constructed throughout the state, which attracted Somali and Oromo nomads with their livestock. The centralized regulations of the wells made it easier for the nomads to settle disputes by taking their queries to government officials who would act as mediators. Long distance caravan trade, a long-time practice in the Horn of Africa, continued unchanged in Ajuran times. Today, numerous ruined and abandoned towns throughout the interior of Somalia and the Horn of Africa are evidence of a once-booming inland trade network dating from the medieval period.[16]

With the centralized supervision of the Ajuran, farms in Afgooye, Bardera and other areas in the Jubba and Shabelle valleys increased their productivity. A system of irrigation ditches known locally as Kelliyo fed directly from the Shebelle and Jubba rivers into the plantations where sorghum, maize, beans, grain and cotton were grown during the gu (Spring in Somali) and xagaa (Summer in Somali) seasons of the Somali calendar. This irrigation system was supported by numerous dikes and dams. To determine the average size of a farm, a land measurement system was also invented with moos, taraab and guldeed being the terms used.

Taxation

The State collected tribute from the farmers in the form of harvested products like durra, sorghum and bun, and from the nomads, cattle, camels sheep and goats. The collecting of tribute was done by a wazir. Luxury goods imported from foreign lands were also presented as gifts to the Garen rulers by the coastal sultans of the state.

A political device that was implemented by the Garen rulers in their realm was a form of ius primae noctis, which enabled them to create marriages that enforced their hegemonic rule over all the important groups of the empire. The rulers would also claim a large portion of the bride's wealth, which at the time was 100 camels.

For trade, the Ajuran Sultanate minted its own Ajuran currency.[17] It also utilized the Mogadishan currency originally minted by the Sultanate of Mogadishu, which later became incorporated into the Ajuran Empire during the early 13th century.[18] Mogadishan coins have been found as far away as the present-day country of the United Arab Emirates in the Middle East.[19]

Urban and maritime centers

The urban centers of Mogadishu, Merca, Barawa, Kismayo and Hobyo and other respective ports became profitable trade outlets for commodities originating from the interior of the State. The Somali farming communities of the hinterland from Jubba and Shebelle valleys brought their crops to the Somali coastal cities, where they were sold to local merchants who maintained a lucrative foreign commerce with ships sailing to and coming from Arabia, Persia, India, Venice, Egypt, Portugal, and as far away as Java and China.[20]

During his travels, Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi (1213–1286) noted that Mogadishu city had already become the leading Islamic center in the region.[21] By the time of the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta's appearance on the Somali coast in 1331, the city was at the zenith of its prosperity. He described Mogadishu as "an exceedingly large city" with many rich merchants, which was famous for its high quality fabric that it exported to Egypt, among other places.[22][23] Battuta added that the city was ruled by a Somali Sultan, Abu Bakr ibn Sayx 'Umar,[24][25] who was originally from Berbera in northern Somalia and spoke both Somali (referred to by Battuta as Benadir, a southern Somali dielect) and Arabic with equal fluency.[25][26] The Sultan also had a retinue of wazirs (ministers), legal experts, commanders, royal eunuchs, and other officials at his beck and call.[25]

Ibn Khaldun (1332 to 1406) noted in his book that Mogadishu was a massive metropolis city that served as the capital of the Ajuran Kingdom. He also claimed that the city of Mogadishu was a very populous city with many wealthy merchants, yet nomad in character. He referred to the characteristics of the inhabitants of Mogadishu as tall swarthy Berbers and called them the people of Al-Somaal.[27]

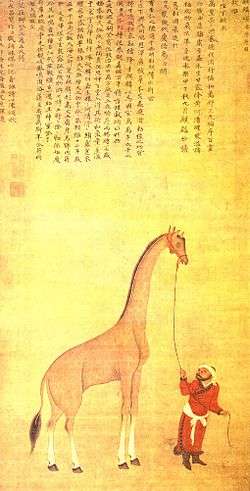

The ruler of the Somali Ajuran Empire sent ambassadors to China to establish diplomatic ties, creating the first ever recorded African community in China and the most notable Somali ambassador in medieval China was Sa'id of Mogadishu who was the first African man to set foot in China. In return, Emperor Yongle, the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), dispatched one of the largest fleets in history to trade with the Somali nation. The fleet, under the leadership of the famed Hui Muslim Zheng He, arrived at Mogadishu the capital of Ajuran Empire while the city was at its zenith. Along with gold, frankincense and fabrics, Zheng brought back the first ever African wildlife to China, which included hippos, giraffes and gazelles.[28][29][30][31]

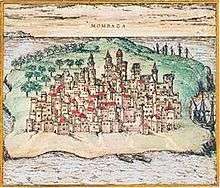

Vasco Da Gama, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted that it was a large city with houses of four or five storeys high and big palaces in its centre and many mosques with cylindrical minarets.[32] In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya sailed to Mogadishu with cloths and spices for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.[33] Mogadishu, the center of a thriving weaving industry known as toob benadir (specialized for the markets in Egypt and Syria),[34] together with Merca and Barawa also served as transit stops for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa.[35] Jewish merchants from the Hormuz also brought their Indian textile and fruit to the Somali coast in exchange for grain and wood.[36]

According to the 16th-century explorer, Leo Africanus indicates that the native inhabitants of the Mogadishu the capital of Ajuran Sultanate polity were of the same origins as the denizens of the northern people of Zeila the capital of Adal Sultanate. They were generally tall with an olive skin complexion, with some being darker and spoke Somali. They would wear traditional rich white silk wrapped around their bodies and have Islamic turbans and coastal people would only wear sarongs, and use Arabic writing script as their lingua franca. Their weaponry consisted of traditional Somali weapons such as swords, daggers, spears, battle axe, and bows, although they received assistance from its close ally the Ottoman Empire and with the import of firearms such as muskets and cannons. Most were Muslims, although a few adhered to heathen bedouin tradition; there were also a number of Abyssinian Christians further inland. Mogadishu itself was a wealthy, powerful and well-built city-state, which maintained commercial trade with kingdoms across the world. The metropolis city was surrounded by walled stone fortifications.[37][38]

Trading relations were established with Malacca in the 15th century,[39] with cloth, ambergris and porcelain being the main commodities of the trade.[40] In addition, giraffes, zebras and incense were exported to the Ming Empire of China, making Somali merchants leaders in the commerce between Asia and Africa.[41] and influencing the Chinese language on Somali in the process. Hindu merchants from Surat and Southeast African merchants from Pate seeking to bypass both the Portuguese blockade and Omani interference used the Somali ports of Merca and Barawa (which were out of the two powers' jurisdiction) to conduct their trade in safety and without interference.[42]

Economy

The Ajuran Sultanate relied on agriculture, taxation and trade for most of its income. Major agricultural towns were located on the Shebelle and Jubba rivers, including Bardera and Afgooye. Situated at the junction of some of the busiest medieval trade routes, the Ajuran and its coastal harbour cities were active participants in the East African gold trade, the Silk Road commerce, trade in the Indian Ocean, and commercial enterprise as far as East Asia.

The Ajuran Sultanate also minted its own Ajuran currency. Many ancient bronze coins inscribed with the names of Ajuran Sultans have been found in the coastal Benadir province, in addition to pieces from Muslim rulers of Southern Arabia and Persia.[17] additionally, Mogadishan coins have been found as far as the United Arab Emirates in the Middle East. Trading routes dating from the ancient and early medieval periods of Somali maritime enterprise were strengthened or re-established, and foreign trade and commerce in the coastal provinces flourished with ships sailing to and coming from a myriad of kingdoms and empires in East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Europe, Middle East, North Africa and East Africa.[6] Through the use of commercial vessels, compasses, multiple port cities, light houses and other technology, the merchants of the Ajuran Sultanate did brisk business with traders from the following states:

Major cities

The Ajuran Kingdom's population back then was huge and stable. The Ajuran State was an influential Somali kingdom that held sway over many cities and towns in central and southern Somalia and eastern Ethiopia during the Middle Ages. With the fall of the Sultanate, a number of these settlements continued to prosper, eventually becoming major cities in present-day Somalia. A few of these cities and towns were also abandoned or destroyed:

- Capital

- Mogadishu (harbor city and current capital of Somalia)

- Port cities

- Merca (port city in the Lower Shebelle region of Somalia)

- Hobyo (harbor city in the Mudug region of Somalia

- Kismayo (port city in the Lower Juba region of Somalia)

- Barawa (port town in the Lower Shebelle region of Somalia)

- Warsheikh (port town in the Middle Shebelle region of Somalia)

- Mareeg (town in the Galguduud region of Somalia)

- Agricultural cities

- Qelafo (town in the Somali Region of Ethiopia)

- Afgooye (town in the Lower Shebelle region of Somalia)

- Beledweyne (a city in Hiran region of Somalia)

- Baidoa (a city in the Bay region of Somalia)

- Bardheere (a city in the Gedo region of Somalia)

- Jowhar (a town in Middle Shebelle region of Somalia)

- Luuq (a town in Gedo region of Somalia)

- Hudur (a city in Bakool region of Somalia)

- Jilib (a city in Middle Juba region of Somalia)

- Other cities

- El Buur (a town in Galguduud region of Somalia)

- Dhusamareb (a city in Galguduud regopn pf Somalia)

- Gondershe (Abandoned, but now a popular tourist attraction site)

- Hannassa (Abandoned)

- Ras Bar Balla (Abandoned)

Culture

The Ajurans facilitated a rich culture with various forms of Somali culture such as architecture, astronomy, festivals, education, music and variety of art like poetry, prose, calligraphy, miniatures, jewellery, cuisine and rich carpet-weaving and textile arts all evolving and flourishing during this period. The majority of the inhabitants were ethnic Somali, but there was also Arab, Persian, and Turkish minority. The vast majority of the population also adhered to Sunni Islam with a Shia minority (mostly those of Persian descent). Somali was the most commonly used language of government and social life while Arabic was most prominently used for religious studies.

The Somali martial art Istunka, also known as Dabshid, was born during their reign. An annual tournament is held every year for it in Afgooye.[43] Carving, known in Somali as qoris, was practiced in the coastal cities of the state. Many wealthy urbanites in the medieval period regularly employed the finest wood and marble carvers in Somalia to work on their interiors and houses. The carvings on the mihrabs and pillars of ancient Somali mosques are some of the oldest on the continent, with Masjid Fakhr al-Din being the 7th oldest mosque in Africa.[44] Artistic carving was considered the province of men similar to how the Somali textile industry was mainly a women's business. Amongst the nomads, carving, especially woodwork, was widespread and could be found on the most basic objects such as spoons, combs and bowls, but it also included more complex structures such as the portable nomadic tent, the aqal.[45]

During its tenure, the Kingdom left an extensive architectural legacy, being one of the major medieval Somali powers engaged in sophisticated and advanced castle, fortresses citadels, cloisters, mosques, temples, fountains, aqueducts, lighthouses, towers and tombs which are all attributed to the Ajuran Kingdom's Somali engineers.[7] The territories that Ajuran held sway over has one of the most medieval ruins in the entire African continent with various of sophisticated and advanced architectures.

These structures include a number of pillar tomb fields, necropolises, castles, fortresses and ruined cities built in that era.[1] In the Marca area, various pillar tombs exist, which local tradition holds were built in the 16th century, when the Ajuran Sultanate's naa'ibs governed the district.[46]

Muslim migration

The late 15th and 17th centuries saw the arrival of Muslim families from Arabia, Persia, India and Spain to the Ajuran Sultanate, the majority of whom settled in the coastal provinces. Some migrated because of the instability in their respective regions,[47] as was the case with the Hadhrami families from the Yemen and the Muslims from Spain fleeing the Inquisition.[48] Others came to conduct business or for religious purposes. Due to their strong tradition in religious learning, the new Muslim communities also enjoyed high status among the Somali ruling elite and commoners.[47] It's believed the Benadiri people are the descendants of these people a tiny minority who inhabit the Benadir region.[49]

Military

The Ajuran State had a strong standing and professionally organized army with which the Garen imams and the governors ruled and protected their subjects. The bulk of the army consisted of mamluke soldiers,[50] who did not have any loyalties to the traditional Somali clan system, thereby making them more reliable. The soldiers were recruited from the inter-riverine area; other recruits came from the surrounding nomadic region. The main corps of the Ajuran army was divided into several sections such as Infantry, consisting of swordsmen, archers and lancers with their light harden steel shield making the Ajuran infantry flexible and swift which easily overwhelmed and destroyed their enemies. The Ajuran cavalry consisted of two sections which were used for different purposes and for different tactics such as light cavalry which depended on high speed rather than heavy armour and using swords, spears and bows with their fast Somali horses. The cuirassier were another Ajuran cavalry equipped with heavy armour and firearms. The Ajuran Kingdom had the largest and most advanced navy in Africa where they would do naval expedition as far as Southeast Asia with their Ottoman allies.[51]

In the early Ajuran period, the army's weapons consisted of traditional Somali weapons such as swords, daggers, spears, battle axe, shield, and bows. The Sultanate received assistance from its close ally the Ottoman Empire, and with the import of firearms through the Muzzaffar port of Mogadishu, the army began acquiring muskets and cannons. The Ottomans would also remain a key ally during the Ajuran-Portuguese wars. Horses used for military purposes were also raised in the interior, and numerous stone fortifications were erected to provide shelter for the army in the interior and coastal districts.[52] In each province, the soldiers were under the supervision of a military commander known as an emir,[50] and the coastal areas and the Indian ocean trade were protected by a navy.[53]

The Ajuran army was among the most advanced fighting force in Africa, being one of the first Africans to use muskets and cannons. The Ajuran soldier would be recruited at a young age of 8 and sent to Afgooye where they would be eminently trained and educated for 10 years in practising the art of fighting, warfare and bravery. They would have a strict diet which made the them very strong and healthy. After their graduation, they would become fearless efficient ruthless professional killing machines. The Ajuran soldier would wear protective helmets and advanced steel armour that covered their body. The Ajuran army would also be paid decently which was enough to financially suppprt their family and house, and during their retirement for serving the kingdom for 25 years would receive large acers of farmland and pension with plenty of livestock animals as a reward for their honourable loyalty for serving and protecting their kingdom.[54][55]

Ajuran-Portuguese wars

The European Age of discovery brought Europe's then superpower the Portuguese empire to the coast of East Africa, which at the time enjoyed a flourishing trade with foreign nations. The wealthy southeastern city-states of Kilwa, Mombasa, Malindi, Pate and Lamu were all systematically sacked and plundered by the Portuguese. Tristão da Cunha then set his eyes on Ajuran Empire territory, where the Battle of Barawa was fought. After a long period of engagement, the Portuguese soldiers burned the city and looted it. However, fierce resistance by the local population and soldiers resulted in the failure of the Portuguese to permanently occupy the city and eventually the Portuguese would be decisively defeated by the powerful Somalis from Ajuran Empire, and the inhabitants who had fled to the interior would eventually return and rebuild the city. Tristão da Cunha was later severely wounded and sought refuge in Socotra islands after losing his men and ships. After losing the war with the Ajuran Empire over the fail attempt to capture Barawa. He decided to re-group his men in Socotra islands and Tristão would set sail for Mogadishu, which was the richest city in Africa. But word had spread of what had happened in Barawa, and a large troop mobilization had taken place. Many horsemen, soldiers and battleships in defense positions were now guarding the city. Nevertheless, Tristão still opted to storm and attempt to conquer the city, although every officer and soldier in his army opposed this, fearing certain defeat if they were to engage their opponents in battle. He decided to leave the Somalis in peace after he realized that they were extremely difficult to conquer and it was Portuguese best interest not to mess with them leaving Ajuran Empire independent.[57] After the battle the city of Barawa quickly recovered from the attack.[58]

Over the next several decades Somali-Portuguese tensions would remain high and the increased contact between Somali sailors and Ottoman corsairs worried the Portuguese who sent a punitive expedition against Mogadishu under João de Sepúvelda but was soundly defeated by the Ajuran naval forces before they even had a chance to reach the Ajuran capital city and João de Sepúvelda was eventually killed in the Battle of Benadir and all his ships were blown up into smithereens.[60] Ottoman-Somali cooperation against the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean reached a high point in the 1580s when Ajuran clients of the Somali coastal cities began to sympathize with the Arabs and Swahilis under Portuguese rule and sent an envoy to the Turkish corsair Mir Ali Beg for a joint expedition against the Portuguese. He agreed and was joined by a large Somali fleet, which began attacking Portuguese colonies in Southeast Africa.[53]

The Somali-Ottoman offensive managed to drive out the Portuguese from several important cities such as Pate, Mombasa and Kilwa. However, the Portuguese governor sent envoys to Portuguese India requesting a large Portuguese fleet. This request was answered and it reversed the previous offensive of the Muslims into one of defense. The Portuguese armada managed to re-take most of the lost cities and began punishing their leaders, but they refrained from attacking Mogadishu and other coastal provinces that belong to the Ajuran Empire.[18][61] Ajuran's Somali forces would eventually militarily defeat the Portuguese. The Ottoman Empire would also remain an economic partner of the Somalis.[6] Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries successive Ajuran Empire defied the Portuguese economic monopoly in the Indian Ocean by employing a new coinage which followed the Ottoman pattern, thus proclaiming an attitude of economic independence in regard to the Portuguese.[62]

Oromo invasion

In the mid-17th century, the Oromo Nation began expanding from its homeland around Lake Abaya in southern Ethiopia towards the southern Somali coast at the time when the Ajuran was at the height of its power.[63][64] The Garen rulers conducted several military expeditions known as the Gaal Madow wars against the Oromo warriors, converting those that were captured to Islam. The Ajuran military supremacy forced the Oromo conquerors to reverse their migrations towards the Christian Solomonids and the Muslim Adalites, devastating the two warring empires in the process.

Decline and successor states

The Ajuran Sultanate slowly declined in power at the end of the 17th century, which paved the way for the ascendance of new Somali powers. The most prominent setbacks against the state were the dethronement of the capital Mogadishu and other coastal cities by the Hawiye Hiraab King,[65] and the defeat of the Silis Kingdom by a former Ajuran general, Ibrahim Adeer, in the interior of the state who then established the Gobroon dynasty. Taxation and the practice of primae noctis were the main catalysts for the revolts against Ajuran rulers. The loss of port cities and fertile farms meant that much needed sources of revenue were lost to the rebels.

See also

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Somalia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- 1 2 3 Njoku, Raphael Chijioke (2013). The History of Somalia. Greenwood. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-313-37857-7.

- ↑ "Ajuran - historical state, Africa". Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ↑ Luling, Virginia (2002). Somali Sultanate: the Geledi city-state over 150 years. Transaction Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-874209-98-0.

- ↑ Luc Cambrézy, Populations réfugiées: de l'exil au retour, p.316

- ↑ Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji. "The Emergence and Role of Political Parties in the Inter-River Region of Somalia from 1947–1960". Ufahamu. 17 (2): 98.

- 1 2 3 4 Shelley, Fred M. (2013). Nation Shapes: The Story behind the World's Borders. ABC-CLIO. p. 358. ISBN 978-1-61069-106-2.

- 1 2 Cassanelli, Lee V. (1982). The Shaping of Somali Society: Reconstructing the History of a Pastoral People, 1600–1900. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-8122-7832-1.

- ↑ Ramsamy, Edward, ed. (2012). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. Volume 2: Africa. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-8176-7.

- 1 2 3 Pouwels, Randall L. (2006). Horn and Crescent: Cultural Change and Traditional Islam on the East African Coast, 800–1900. African Studies. 53. Cambridge University Press. p. 15.

- ↑ Njoku (2013), p. 41.

- ↑ Northeast African Studies. Volume 11. African Studies Center, Michigan State University. 1989. p. 115.

- ↑ Cassanelli (1982), p. 102.

- ↑ Sheik-ʻAbdi, ʻAbdi ʻAbdulqadir (6 April 1993). "Divine madness: Moḥammed ʻAbdulle Ḥassan (1856-1920)". Zed Books. Retrieved 6 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Lewis, I. M. (1988). A Modern History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa (2nd, revised ed.). Westview Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-8133-7402-2.

- 1 2 3 Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8108-6604-1.

- ↑ Cassanelli (1982), p. 149.

- 1 2 Ali, Ismail Mohamed (1970). Somalia Today: General Information. Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Somali Democratic Republic. p. 206. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- 1 2 Stanley, Bruce (2007). "Mogadishu". In Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E. Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5.

- ↑ Chittick, H. Neville (1976). An Archaeological Reconnaissance in the Horn: The British-Somali Expedition, 1975. British Institute in Eastern Africa. pp. 117–133.

- ↑ Journal of African History pg.50 by John Donnelly Fage and Roland Anthony Oliver

- ↑ Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. US: ABC-CLIO. p. 252.

- ↑ Helen Chapin Metz (1992). Somalia: A Country Study. US: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0844407755.

- ↑ P. L. Shinnie, The African Iron Age, (Clarendon Press: 1971), p.135

- ↑ Versteegh, Kees (2008). Encyclopedia of Arabic language and linguistics, Volume 4. Brill. p. 276. ISBN 9004144765.

- 1 2 3 David D. Laitin, Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a State, (Westview Press: 1987), p. 15.

- ↑ Chapurukha Makokha Kusimba, The Rise and Fall of Swahili States, (AltaMira Press: 1999), p.58

- ↑ Brett, Michael (1 January 1999). "Ibn Khaldun and the Medieval Maghrib". Ashgate/Variorum. Retrieved 6 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Wilson, Samuel M. "The Emperor's Giraffe", Natural History Vol. 101, No. 12, December 1992 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ↑ Rice, Xan (25 July 2010). "Chinese archaeologists' African quest for sunken ship of Ming admiral". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Could a rusty coin re-write Chinese-African history?". BBC News. 18 October 2010.

- ↑ "Zheng He'S Voyages to the Western Oceans 郑和下西洋". People.chinese.cn. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ↑ Da Gama's First Voyage pg.88

- ↑ East Africa and its Invaders pg.38

- ↑ Alpers, Edward A. (1976). "Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa, c. 1500-1800". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 9 (1): 35. doi:10.2307/217389. JSTOR 217389.

- ↑ Harris, Nigel (2003). The Return of Cosmopolitan Capital: Globalization, the State and War. I.B.Tauris. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-86064-786-4.

- ↑ Barendse, Rene J. (2002). The Arabian Seas: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-45835-7.

- ↑ (Africanus), Leo (6 April 1969). "A Geographical Historie of Africa". Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Retrieved 6 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Dunn, Ross E. (1987). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta. Berkeley: University of California. p. 373. ISBN 0-520-05771-6. , p. 125

- ↑ Alpers (1976), p. 30.

- ↑ Chinese Porcelain Marks from Coastal Sites in Kenya: aspects of trade in the Indian Ocean, XIV-XIX centuries. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1978 pg 2

- ↑ East Africa and its Invaders pg.37

- ↑ Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa pg.45

- ↑ Mukhtar (2003), p. 28.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 2013-08-19. ArchNet - Masjid Fakhr al-Din

- ↑ Culture and customs of Somalia By Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi pg 97

- ↑ Cassanelli (1982), p. 97.

- 1 2 Luling (2002), p. 18.

- ↑ The origins and development of Mogadishu pg. 34 by Ahmed Dueleh Jama

- ↑ Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye (2001). Culture and Customs of Somalia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0313313334. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- 1 2 Cassanelli (1982), p. 90.

- ↑ Abdurahman, Abdullahi (18 September 2017). "Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1". Adonis and Abbey Publishers. Retrieved 6 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Cassanelli (1982), p. 92.

- 1 2 Welch (1950), p. 25.

- ↑ Cassanelli (1982), p. 104.

- ↑ Welch, Sidney R. (1950). Portuguese rule and Spanish crown in South Africa, 1581-1640. Juta.

- ↑ Maritime Discovery: A History of Nautical Exploration from the Earliest Times pg 198

- ↑ The History of the Portuguese, During the Reign of Emmanuel pg.287

- ↑ The book of Duarte Barbosa - Page 30

- ↑ Tanzania notes and records: the journal of the Tanzania Society pg 76

- ↑ The Portuguese period in East Africa – Page 112

- ↑ Four centuries of Swahili verse: a literary history and anthology – Page 11

- ↑ COINS FROM MOGADISHU, c. 1300 to c. 1700 by G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville pg 36

- ↑ Cassanelli (1982), p. 114.

- ↑ Cerulli, Somalia 1: 65–67

- ↑ Lewis (1988), p. 37.