Kanem–Bornu Empire

| Kanem Empire | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 700–1380 | |||||||

Flag of Kanem also known as Organa from Dulcerta atlas 1339 | |||||||

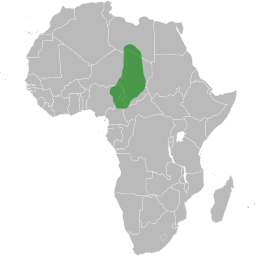

Influence of Kanem Empire around 1200 AD | |||||||

| Capital | Njimi | ||||||

| Common languages | Teda | ||||||

| Religion | traditional beliefs, later Islam | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| King (Mai) | |||||||

• c. 700 | Sef | ||||||

• 1382–1387 | Omar I | ||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||

• Established | c. 700 | ||||||

• Invaded and forced to move, thus establishing new Bornu Empire | 1380 | ||||||

| Area | |||||||

| 1200[1] | 776,996 km2 (300,000 sq mi) | ||||||

| |||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Northern Nigeria |

|

|

Timeline

|

|

By ethnicity

|

|

By topic

|

|

By Province

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Chad |

|

|

|

The Kanem–Bornu Empire was an empire that existed in modern Chad and Nigeria. It was known to the Arabian geographers as the Kanem Empire from the 9th century AD onward and lasted as the independent kingdom of Bornu (the Bornu Empire) until 1900. The Kanem Empire (c. 700–1380) was located in the present countries of Chad, Nigeria and Libya.[2] At its height it encompassed an area covering not only most of Chad, but also parts of southern Libya (Fezzan) and eastern Niger, northeastern Nigeria and northern Cameroon. The Bornu Empire (1380s–1893) was a state of what is now northeastern Nigeria, in time becoming even larger than Kanem, incorporating areas that are today parts of Chad, Niger, Sudan, and Cameroon; is existed from 1380s to 1893. The early history of the Empire is mainly known from the Royal Chronicle or Girgam discovered in 1851 by the German traveller Heinrich Barth.

Theories on the origin of Kanem

Kanem was located at the southern end of the trans-Saharan trade route between Tripoli and the region of Lake Chad. Besides its urban elite it also included a confederation of nomadic peoples who spoke languages of the Teda–Daza (Toubou) group.

Founding by immigrants c. 600 BC

The origins of Kanem are unclear. Some older histories connect the creation of Kanem-Bornu with exodus from the collapsed Assyrian Empire c. 600 BC to the northeast of Lake Chad.[3] More recent theories tend to support the idea of a closer origin for the migration.[4]

Founding by local Kanembu (Dugua) c. 700 AD

According to a more accepted theory, the kingdom of Kanem began forming around 700 AD under the nomadic Tebu-speaking Kanembu. The Kanembu were supposedly forced southwest towards the fertile lands around Lake Chad by political pressure and desiccation in their former range. The area already possessed independent, walled city-states belonging to the Sao culture. Under the leadership of the Duguwa dynasty, the Kanembu would eventually dominate the Sao, but not before adopting many of their customs.[5] War between the two continued up to the late 16th century.

Agisymba origin

One theory proposes that the lost state of Agisymba (mentioned by Ptolemy in the middle of the 2nd century AD) was the antecedent of the Kanem Empire.[6]

Duguwa Dynasty (Kanembu)

Kanem was located at the southern end of the trans-Saharan trade route between Tripoli and the region of Lake Chad. The Kanembu eventually abandoned their nomadic lifestyle and founded a capital around 700 AD under the first documented Kanembu king ("mai") known as Sef of Saif. The capital of N'jimi (the word for "south" in the Teda language) grew in power and influence under Sef's son, Dugu. This transition marked the beginning of the Duguwa Dynasty. The mais of the Duguwa were regarded as divine kings and belonged to the ruling establishment known as the Magumi. Despite changes in dynastic power, the magumi and the title of mai would persevere for over a thousand years.

Kanem is mentioned as one of three great empires in Bilad el-Sudan, by Al Yaqubi in 872.[7]

Adoption of Islam c. 1068 AD

Rise of the Sayfawa dynasty

The major factor that influenced the later history of the state of Kanem was the early penetration of Islam. North African traders, Berbers and Arabs, brought the new religion. Towards 1068, Hummay, a member of the Sayfawa establishment, who was already a Muslim, discarded the last Duguwa King Selma from power and thus established the new dynasty of the Sayfawa. Islam offered the Sayfawa rulers the advantage of new ideas from Arabia and the Mediterranean world, as well as literacy in administration. But many people resisted the new religion favouring traditional beliefs and practices. When Hummay had assumed power on the basis of his strong Islamic following, for example, it is believed that the Duguwa/Kanembu began some kind of internal opposition. This pattern of conflict and compromise with Islam occurs repeatedly in Chadian history.

Foundation of the new capital Njimi

When the ruling dynasty changed, the royal establishment abandoned its capital of Manan and settled in the new capital Njimi further south of Kanem (the word for "south" in the Teda language). By the 13th century, Kanem's rule expanded. At the same time, the Kanembu people drew closer to the new rulers and increased the growing population in the new capital of Njimi. Even though the Kanembu became the main power-base of the Sayfuwa, Kanem's rulers continued to travel frequently throughout the kingdom and especially towards Bornu, west of lake Chad. Herders and farmers alike recognized the government's power and acknowledged their allegiance by paying tribute.

Expansion to Bornu

Mai Dunama Dabbalemi

Kanem's expansion peaked during the long and energetic reign of Mai Dunama Dabbalemi (ca. 1203–1242), also of the Sayfawa dynasty. Dabbalemi initiated diplomatic exchanges with sultans in North Africa and apparently arranged for the establishment of a special hostel in Cairo to facilitate pilgrimages to Mecca. During his reign, he declared jihad against the surrounding tribes and initiated an extended period of conquest. After consolidating their territory around Lake Chad the Fezzan region (in present-day Libya) fell under Kanem's authority, and the empire's influence extended westward to Kano (in present-day Nigeria) and thus included Bornu, eastward to Ouaddaï, and southward to the Adamawa grasslands (in present-day Cameroon). Portraying these boundaries on maps can be misleading, however, because the degree of control extended in ever-weakening gradations from the core of the empire around Njimi to remote peripheries, from which allegiance and tribute were usually only symbolic. Moreover, cartographic lines are static and misrepresent the mobility inherent in nomadism and migration, which were common. The loyalty of peoples and their leaders was more important in governance than the physical control of territory.

Dabbalemi devised a system to reward military commanders with authority over the people they conquered. This system, however, tempted military officers to pass their positions to their sons, thus transforming the office from one based on achievement and loyalty to the mai into one based on hereditary nobility. Dabbalemi was able to suppress this tendency, but after his death, dissension among his sons weakened the Sayfawa Dynasty. Dynastic feuds degenerated into civil war, and Kanem's outlying peoples soon ceased paying tribute.

Shift of the Sayfuwa court from Kanem to Bornu

| Bornu Empire | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1380s–1893 | |||||||||||

Flag of Bornu, also known as Organa, from Vallseca atlas of 1439 | |||||||||||

Bornu Empire extent c.1750 | |||||||||||

| Capital | Ngazargamu | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Kanuri | ||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King (Mai) | |||||||||||

• 1381–1382 | Said of Bornu | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Established | 1380s | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1893 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1800[8] | 50,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| 1892[9] | 129,499 km2 (50,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1892[10] | 5000000 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

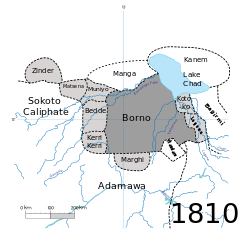

By the end of the 14th century, internal struggles and external attacks had torn Kanem apart. Between 1359 and 1383, seven mais reigned, but Bulala invaders (from the area around Lake Fitri to the east) killed five of them. This proliferation of mais resulted in numerous claimants to the throne and led to a series of internecine wars. Finally, around 1380 the Bulala forced Mai Umar Idrismi to abandon Njimi and move the Kanembu people to Bornu on the western edge of Lake Chad.[11] Over time, the intermarriage of the Kanembu and Bornu peoples created a new people and language, the Kanuri.

But even in Bornu, the Sayfawa Dynasty's troubles persisted. During the first three-quarters of the 15th century, for example, fifteen mais occupied the throne. Then, around 1460 Mai Ali Dunamami defeated his rivals and began the consolidation of Bornu. He built a fortified capital at Ngazargamu, to the west of Lake Chad (in present-day Nigeria), the first permanent home a Sayfawa mai had enjoyed in a century. So successful was the Sayfawa rejuvenation that by the early 16th century Mai Idris Katakarmabe (1487–1509) was able to defeat the Bulala and retake Njimi, the former capital. The empire's leaders, however, remained at Ngazargamu because its lands were more productive agriculturally and better suited to the raising of cattle. Ali Gaji was the first ruler of the empire to assume the title of Caliph.[12]

Kanem-Bornu Period

With control over both capitals, the Sayfawa dynasty became more powerful than ever. The two states were merged, but political authority still rested in Bornu. Kanem-Bornu peaked during the reign of the statesman Mai Idris Alooma (c. 1571–1603). Aluma is remembered for his military skills, administrative reforms, and Islamic piety. His main adversaries were the Hausa to the west, the Tuareg and Toubou to the north, and the Bulala to the east. One epic poem extols his victories in 330 wars and more than 1,000 battles. His innovations included the employment of fixed military camps (with walls); permanent sieges and "scorched earth" tactics, where soldiers burned everything in their path; armored horses and riders; and the use of Berber camelry, Kotoko boatmen, and iron-helmeted musketeers trained by Turkish military advisers. His active diplomacy featured relations with Tripoli, Egypt, and the Ottoman Empire, which sent a 200-member ambassadorial party across the desert to Aluma's court at Ngazargamu. Aluma also signed what was probably the first written treaty or cease-fire in Chadian history.

Aluma introduced a number of legal and administrative reforms based on his religious beliefs and Islamic law (sharia). He sponsored the construction of numerous mosques and made a pilgrimage to Mecca, where he arranged for the establishment of a hostel to be used by pilgrims from his empire. As with other dynamic politicians, Aluma's reformist goals led him to seek loyal and competent advisers and allies, and he frequently relied on slaves who had been educated in noble homes. Aluma regularly sought advice from a council composed of heads of the most important clans. He required major political figures to live at the court, and he reinforced political alliances through appropriate marriages (Aluma himself was the son of a Kanuri father and a Bulala mother).

Kanem-Bornu under Aluma was strong and wealthy. Government revenue came from tribute (or booty, if the recalcitrant people had to be conquered), sales of slaves, and duties on and participation in trans-Saharan trade. Unlike West Africa, the Chadian region did not have gold. Still, it was central to one of the most convenient trans-Saharan routes. Between Lake Chad and Fezzan lay a sequence of well-spaced wells and oases, and from Fezzan there were easy connections to North Africa and the Mediterranean Sea. Many products were sent north, including natron (sodium carbonate), cotton, kola nuts, ivory, ostrich feathers, perfume, wax, and hides, and slaves. Imports included salt, horses, silks, glass, muskets, and copper.

Aluma took a keen interest in trade and other economic matters. He is credited with having the roads cleared, designing better boats for Lake Chad, introducing standard units of measure for grain, and moving farmers into new lands. In addition, he improved the ease and security of transit through the empire with the goal of making it so safe that "a lone woman clad in gold might walk with none to fear but God."

Successors

Most of the successors of Idris Alooma are only known from the meagre information provided by the Diwan. Some of them are noted for having undertaken the pilgrimage to Mecca others for their piety. In the eighteenth century Bornu was affected by several long-lasting famines.[13]

Decline of the Bornu Empire

The administrative reforms and military brilliance of Aluma sustained the empire until the mid-17th century, when its power began to fade. By the late 18th century, Bornu rule extended only westward, into the land of the Hausa of modern Nigeria. The empire was still ruled by the Mai who was advised by his councilors (kokenawa) in the state council or "nokena".[14] The members of his Nokena council included his sons and daughters and other royalty (the Maina) and non-royalty (the Kokenawa, "new men"). The Kokenawa included free men and slave eunuchs known as kachela. The latter "had come to play a very important part in Bornu politics, as eunuchs did in many Muslim courts."[15]

Fulani Jihad

Around that time, Fulani people, invading from the west, were able to make major inroads into Bornu. By the early 19th century, Kanem-Bornu was clearly an empire in decline, and in 1808 Fulani warriors conquered Ngazargamu. Usman dan Fodio led the Fulani thrust and proclaimed a jihad (holy war) on the irreligious Muslims of the area. His campaign eventually affected Kanem-Bornu and inspired a trend toward Islamic orthodoxy.

Muhammad al-Kanemi

But Muhammad al-Amin al-Kanemi contested the Fulani advance. Kanem was a Muslim scholar and non-Sayfawa warlord who had put together an alliance of Shuwa Arabs, Kanembu, and other seminomadic peoples. He eventually built in 1814 a capital at Kukawa (in present-day Nigeria). Sayfawa mais remained titular monarchs until 1846. In that year, the last mai, in league with the Ouaddai Empire, precipitated a civil war. It was at that point that Kanemi's son, Umar, became king, thus ending one of the longest dynastic reigns in international history.[16]

Post-Sayfawa Era

Although the dynasty ended, the kingdom of Kanem-Bornu survived. Umar eschewed the title mai for the simpler designation shehu (from the Arabic shaykh), could not match his father's vitality, and gradually allowed the kingdom to be ruled by advisers (wazirs). Bornu began a further decline as a result of administrative disorganization, regional particularism, and attacks by the militant Ouaddai Empire to the east. The decline continued under Umar's sons. In 1893, Rabih az-Zubayr led an invading army from eastern Sudan and conquered Bornu. Following his expulsion shortly thereafter, the state was absorbed by the British ruled entity which eventually became known as Nigeria. From that point on, a remnant of the old kingdom was (and still is) allowed to continue to exist in subjection to the various Governments of the country as the Borno Emirate. He was defeated by French soldiers in 1900.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ Shillington, page 733

- ↑ "Kanem-Bornu". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ Lange, Founding of Kanem, 31–38.

- ↑ An overview of these discussions are gathered in the web page of the German scholar Dierk Lange, author of this theory: Reviews of Dierk Lange – Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa

- ↑ Urvoy, Empire, 3–35; Trimingham, History, 104–111.

- ↑ "The Mune as the Ark of the Covenant between Duguwa (Kanembu) and Sefuwa (Kanembu - Mayi)" Borno Museum Society Newsletter 66–67 (2006), 15–25. (The article has a map (page 6) of the ancient Central Sahara and proposes to identify Agisymba of 100 CE with the early Kanem state).

- ↑ Levtzion, Nehemia (1973). Ancient Ghana and Mali. New York: Methuen & Co Ltd. p. 3. ISBN 0841904316.

- ↑ Oliver, page 12

- ↑ Hughes, page 281

- ↑ Hughes, page 281

- ↑ Smith, "Early states", 179; Lange, "Kingdoms and peoples", 238; Barkindo, "Early states", 245–6.

- ↑ Nehemia Levtzion, Randall Pouwels. The History of Islam in Africa. Ohio University Press. p. 81.

- ↑ Lange, Diwan, 81-82.

- ↑ Brenner, Shehus, 46, 104–7.

- ↑ Ajayi, J. F. Ade.; Espie, Ian, eds. (1965). A Thousand Years of West African History: A Handbook for Teachers and Students. Ibadan, Nigeria: Ibadan University Press. p. 296.

- ↑ Brenner, Shehus, 64–66.

- ↑ Hallam, Life, 257–275.

Bibliography

- Alkali, Nur, and Bala Usman, eds., Studies in the History of Pre-Colonial Borno (Zaria: Northern Nigerian Publishing, 1983)

- Barkindo, Bawuro: "The early states of the Central Sudan: Kanem, Borno and some of their neighbours to c. 1500 AD.", in: J. Ajayi und M. Crowder (ed.), History of West Africa, Bd. I, 3rd ed. Harlow 1985, 225–254.

- Barth, Heinrich: Travel and Discoveries in North and Central Africa, vol. II, New York, 1858, 15–29, 581–602.

- Brenner, Louis, The Shehus of Kukawa, Oxford 1973.

- Kanem-Borno, in Thomas Collelo, ed. Chad: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1988.

- Dewière, Rémi, ‘Regards croisés entre deux ports de désert’, Hypothèses, 2013, 383–93

- Cohen, Ronald: The Kanuri of Bornu, New York 1967.

- Hallam, W.: The life and Times of Rabih Fadl Allah, Devon 1977.

- Hiribarren, Vincent, A History of Borno: Trans-Saharan African Empire to Failing Nigerian State (London: Hurst & Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Hughes, William (2007). A class-book of modern geography (Paperback). Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. p. 390 Pages. ISBN 1-4326-8180-X.

- Lange, Dierk: Le Dīwān des sultans du Kanem-Bornu, Wiesbaden 1977.

- -- A Sudanic Chronicle: The Borno Expeditions of Idris Alauma (1564–1576), Stuttgart 1987.

- -- "Ethnogenesis from within the Chadic state", Paideuma, 39 (1993), 261–277.

- -- "The Chad region as a crossroads", in: M. Elfasi (Hg.), General History of Africa, vol. III, UNESCO, London 1988, pp. 436–460.

- -- "The kingdoms and peoples of Chad", in: D. T. Niane (ed.), General History of Africa, vol. IV, UNESCO, London 1984, pp. 238–265.

- --: "An introduction to the history of Kanem-Borno: The prologue of the Dīwān", Borno Museum Society Newsletter 76–84 (2010), 79–103.

- --: The Founding of Kanem by Assyrian Refugees ca. 600 BCE: Documentary, Linguistic, and Archaeological Evidence, Boston 2011.

- Lavers, John, ‘Adventures in the chronology of the states of the Chad basin’, ed. by Daniel Barreteau and Charlotte de Graffenried (presented at the Datation et chronologie dans le bassin du lac Tchad. Dating and chronology in the lake Chad basin, Bondy: Orstom, 1993), pp. 255–67

- Levtzion, Nehemia, and John Hopkins: Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History, Cambridge 1981.

- Nachtigal, Gustav: Sahara und Sudan, Berlin, 1879–1881, Leipzig 1989 (Nachdruck Graz 1967; engl. Übers. von Humphrey Fisher).

- Oliver, Roland & Anthony Atmore (2005). Africa Since 1800, Fifth Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 405 Pages. ISBN 0-521-83615-8.

- Shillington, Kevin (2005). Encyclopedia of African History Volume 1 A–G. New York: Routledge. pp. 1912 pages. ISBN 1-57958-245-1.

- Smith, Abdullahi: The early states of the Central Sudan, in: J. Ajayi and M. Crowder (ed.), History of West Africa, vol. I, 1st ed., London, 1971, 158–183.

- Urvoy, Yves: L'empire du Bornou, Paris 1949.

- Trimingham, Spencer: A History of Islam in West Africa, Oxford 1962.

- Urvoy, Yves: L'empire du Bornou, Paris 1949.

- Van de Mieroop, Marc: A History of the Ancient Near East, 2nd ed., Oxford 2007.

- Zakari, Maikorema: Contribution à l'histoire des populations du sud-est nigérien, Niamey 1985.

- Zeltner, Jean-Claude : Pages d'histoire du Kanem, pays tchadien, Paris 1980.

Further reading

- Barkindo, Bawuro, "The early states of the Central Sudan: Kanem, Borno and some of their neighbours to c. 1500 A.D.", in: J. Ajayi und M. Crowder (Hg.), History of West Africa, Bd. I, 3. Ausg. Harlow 1985, 225–254.

- Lange, Dierk, Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa: Africa-Centred and Canaanite-Israelite Perspectives, Dettelbach 2004. (the book suggests a pre-Christian origin of Kanem in connection with the Phoenician expansion)

- Urvoy, Yves, L'empire du Bornou, Paris 1949.

- Lange, Dierk, "Immigration of the Chadic-speaking Sao towards 600 BCE" Borno Museum Society Newsletter, 72–75 (2008), 84–106.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bornu. |