Zazas

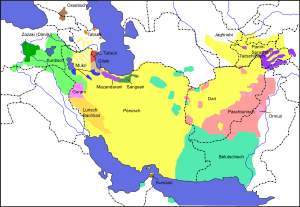

The Zazas (also known as Kird, Kirmanc or Dimili)[6] are a people in eastern Turkey who natively speak the Zaza language. Their heartland, the Dersim region, consists of Tunceli, Bingöl provinces and parts of Elazığ, Erzincan and Diyarbakır provinces.[2] Zazas generally[7] consider themselves ethnic Kurds[8][5][9][10] and they are often described as Zaza Kurds.[6][11][12][13][14]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2 to 4 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Diaspora: Approx. 300,000[2] Australia, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States.[3][4] | |

| Languages | |

| Zaza, Kurdish,[3] and Turkish | |

| Religion | |

| Alevism and Sunni Islam[5] |

Demographics

The exact number of Zazas is unknown, due to the absence of recent and extensive census data. The last census on language in Turkey was held in 1965, where 150,644 people ticked Zaza as their first language and 112,701 and second language.[15] More recent data from 2005 suggests that the Zaza-speaking population varies from approximately 2 to 4 million.[1] It is also important to note that many Zazas only learned Kurmanji Kurdish as it was believed that the Zaza language was a mere Kurdish offshoot.[3] According to a 2019 KONDA survey, about 1.5 million people identified themselves as Zaza.[16]

Following the 1980 Turkish coup d'état, many intellectual minorities, including Zazas, emigrated from Turkey towards Europe, Australia and the United States. The largest part of the Zaza diaspora is based in Europe, predominantly in Germany.[4]

Ethnic consciousness

While Zazas largely consider themselves Kurds,[7] some researches do consider Zazas as an ethnic group and treat them as such in their academic work.[17]

Zazas and Kurmanji-speaking Kurds

.jpg)

Kurmanji Kurds and Zazas have for centuries lived in the same areas in Anatolia. In the 1920s and 1930s, Zazas played a key role in the rise of Kurdish nationalism with their rebellions against the Ottoman Empire and later the Republic of Turkey. During the Sheikh Said rebellion in 1925, the Zaza Sheikh Said and his supporters rebelled against the newly established Turkey for its nationalist and secular ideology.[19] Many Zazas subsequently joined the Kurdish nationalist Xoybûn, Society for the Rise of Kurdistan and other movements where they rose to prominence.[20]

In 1937 during the Dersim rebellion, Zazas once again rebelled against the Turks. This time the rebellion was led by Seyid Riza and ended with a massacre of thousands of Kurdish and Zaza civilians, while many were internally displaced due to the conflict.[21] Zazas also participated in the Koçgiri rebellion in 1920.[22]

Sakine Cansız, a Zaza from Tunceli was a founding member of Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), and like her many Zazas joined the rebels, including the promiment Besê Hozat.[23][24] Many Zaza politicians are also to be found in the fraternal Kurdish parties of the Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) and Democratic Regions Party (DBP), like Selahattin Demirtaş, Aysel Tuğluk, Ayla Akat Ata and Gültan Kışanak.

On the other hand, some Zazas have publicly stated they do not consider themselves Kurdish including Hüseyin Aygün, a CHP politician from Tunceli.[25][26]

A scientific report from 2005 concluded that Zazas share the same genetical pattern as other 'Kurdish groups' and did not support the hypothesis of Zazas originating from Northern Iran.[27]

Language

Zaza is a Northwest Iranian language, spoken in the east of modern Turkey, with approximately 2 to 3 million speakers. There is a division between Northern and Southern Zaza, most notably in phonological inventory, but Zaza as a whole forms a dialect continuum, with no recognized standard.[1] The first written statements in the Zaza language were compiled by the linguist Peter Lerch in 1850. Two other important documents are the religious writings of Ehmedê Xasi of 1898,[29] and of Usman Efendiyo Babıc (published in Damascus in 1933); both of these works were written in the Arabic alphabet.[30] The state-owned TRT Kurdî airs shows in Zaza.[3]

The Zaza language is considered to be an endangered language due to a long history of persecution, and targeting by the Turkish government. The lack of documentation, and the decline in the number of native Zaza speakers can largely be attributed to the Turkish laws put in place in the mid-1920s, after the creation of the Republic of Turkey. These laws banned the Kurdish language, of which Zaza was often erroneously considered a dialect, from being spoken in public, being written down, and being published. One specific law, the Language Ban Act of 1985, explicitly stated that only Turkish could be spoken in public, not only greatly discouraged the use of Zaza, but it also endangered the cultural identity of the Zaza. Only until very recently has Zaza been allowed back in the public sphere of Turkey. But the effects of these past policies are still very present as there has been a lack of literature and substantial development in the language.

During the 1980s, Zaza language became popular among diaspora Zazas after meager efforts which was followed by publications in Zaza in Turkey.[31]

Religion

Around half of the Zaza population adhere to Alevism and these predominantly live around Tunceli. The other half adhere to Sunni Islam, both Hanafi and Shafi‘i,[32] whereas the Shafi‘i followers are mostly Naqshbandi.[33] Historically, a Christian Zaza population existed in Gerger.[34]

Zaza nationalism

Zaza nationalism is an ideology that supports the preservation of Zaza people between Turks and Kurds in Turkey. Turkish nationalist Hasan Reşit Tankut proposed in 1961 to create a corridor between Zaza-speakers and Kurmanji-speakers to hasten Turkification. In some cases in the diaspora, Zazas turned to this ideology because of the more visible differences between them and Kurmanji-speakers.[35] Zaza nationalism was further boosted when Turkey abandoned its assimilatory policies which made some Zazas begin considering themselves as a separate ethnic group.[36] In the diaspora, some Zazas turned to Zaza nationalism in the freer European political climate. On this, Ebubekir Pamukchu, the founder of the Zaza national movement stated: "From that moment I became Zaza."[37] Zaza nationalists fear Turkish and Kurdish influence and aim at protecting Zaza culture and language rather than seeking any kind of autonomy within Turkey.[38]

According to researcher Ahmet Kasımoğlu, Zaza nationalism is a Turkish and Armenian attempt to divide Kurds.[39]

See also

Further reading

- "Language, Religion, and Emplacement of Zazaki Speakers". Sevda Arslan, University of Notre Dame, USA. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, suppl. Special Issue: Kurdish Diaspora; Istanbul Vol. 6, Iss. 2, (Aug 2019): 11-22.

Notes

- Endangered Language Alliance.

- Asatrian (1995).

- Ziflioğlu (2011).

- Arakelova (1999), p. 400.

- Kehl-Bodrogi, Otter-Beaujean & Kellner-Heikele (1997), p. 13.

- Malmîsanij (1996), p. 1.

- Kehl-Bodrogi (1999), p. 442.

- Arakelova (1999), p. 397.

- Nodar (2012).

- Postgate (2007), p. 148.

- Taylor (1865), p. 39.

- van Bruinessen (1989), p. 1.

- Özoğlu (2004), p. 35.

- Kaya (2009).

- Dündar (2000), p. 216.

- Sputnik (2019).

- Keskin (2015), pp. 94-95.

- Chantre (1881).

- Kaya (2009), p. IX.

- Kasımoğlu (2012), pp. 653-657.

- Cengiz (2011).

- Lezgîn (2010).

- Milliyet (2013).

- Hürriyet (2013).

- Haber Vaktim (2011).

- Haber Türk (2013).

- Nasidze et al. (2005).

- Gippert (1999).

- Malmîsanij (1996), pp. 1-2.

- Keskin (2015), p. 108.

- Bozdağ & Üngör (2011).

- Werner (2012), pp. 24 & 29.

- Kalafat (1996), p. 290.

- Werner (2012), p. 25.

- van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (28 January 2009). "Is Ankara Promoting Zaza Nationalism to Divide the Kurds?". Terrorism Focus. 6 (3). Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Indigenous Peoples: An Encyclopedia of Culture, History, and Threats to . Victoria R. Williams

- Arakelova (1999), p. 401.

- Zulfü Selcan, Grammatik der Zaza-Sprache, Nord-Dialekt (Dersim-Dialekt), Wissenschaft & Technik Verlag, Berlin, 1998, p. 23.

- Kasımoğlu (2012), p. 654.

Bibliography

- Arakelova, Victoria (1999), "The Zaza People as a New Ethno-Political Factor in the Region", Iran & the Caucasus, 3/4: 397–408 – via JSTOR

- Asatrian, Garnik (1995), "Dimli", Iranica Online, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Bozdağ, Cem; Üngör, Uğur (2011), Zazas and zazaki, Zazaki.de, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Cengiz, Orhan Kemal (2011), "Can Kurds rely on the Turkish state?", Today's Zaman, archived from the original on 29 November 2014, retrieved 27 April 2015

- Chantre, Ernest (1881), Maximilien-Étienne-Émile Barry, Mission scientifique de Mr. Ernest Chantre sous-directeur du Muséum de Lyon dans la haute Mésopotamie, le Kurdistan et le Caucase: 2018.R.23-38 Kurdes Zazas, Diarbékir (Kurdistan) (in English and French), Online Archive of California, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Dündar, Fuat (2000), Türkiye Nüfus Sayımlarında Azınlıklar (in Turkish), Chiviyazıları Yayınevi, ISBN 9758086774

- Endangered Language Alliance, "Zaza", elalliance.org, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Gippert, Jost (1999), Iranische Sprachen / Iranian Languages, Thesaurus Indogermanischer Text- und Sprachmaterialien (TITUS), retrieved 7 June 2020

- Haber Türk (2013), Meclis'e sıçrayan polemi (in Turkish), retrieved 19 February 2016

- Haber Vaktim (2011), "Kürt değilim Türkmenim" (in Turkish), archived from the original on 11 September 2013, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Hürriyet (2013), Bese Hozat'ın annesi: Kızım gelirse 7 kurban keseceğim (in Turkish), retrieved 7 June 2020

- Kalafat, Yaşar (1996). "Anadolu Türk Halk Sufizmi: Zazalar" (PDF) (in Turkish). Ankara: Dinler Tarihi Derneği Yayınları. Retrieved 7 June 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kasımoğlu, Ahmet (2012), "Xoybûn de cayê Kirdan" (PDF), II. Uluslararası Zaza Tarihi ve Kültürü Sempozyumu (in Zazaki), Bingöl Üniversitesi Yayınları: 654–676

- Kaya, Mehmed S. (2009), The Zaza Kurds of Turkey : a Middle Eastern minority in a globalised society, London: Tauris Academic Studies, ISBN 9781845118754

- Kausen, Ernst (2006), Zaza (PDF) (in German), retrieved 7 June 2020

- Kehl-Bodrogi; Otter-Beaujean; Kellner-Heikele (1997), Syncretistic religious communities in the Near East : collected papers of the international symposium "Alevism in Turkey and comparable syncretistic religious communities in the Near East in the past and present", Berlin, 14-17 April 1995, Leiden: Brill Publishing, ISBN 9789004108615

- Kehl-Bodrogi, Krisztina (October 1999), "Kurds, Turks, or a People in their own Right? Competing Collective Identities Among the Zazas", The Muslim World, 89 (3–4), doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.1999.tb02757.x

- Keskin, Mesut (2015), Zaza Dili (Zaza Language) (PDF) (in Turkish), 1, Bingöl: Bingöl Üniversitesi Yaşayan Diller Enstitüsü Dergisi, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Köhler, herausgegeben von Bärbel (1998), Religion und Wahrheit : religionsgeschichtliche Studien : Festschrift für Gernot Wiessner zum 65. Geburtstag, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 385–399, ISBN 978-3447039758

- Lezgîn, Roşan (2010), "Among Social Kurdish Groups – General Glance at Zazas", Zazaki.net, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Malmîsanij, Mehemed (1996), Kırd, Kırmanc, Dımıli veya Zaza Kürtleri (PDF) (in Turkish and Zazaki), Deng, pp. 1–43, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Milliyet (2013), Sakine Cansız Zazaca ağıtlarla toprağa verildi (in Turkish), retrieved 7 June 2020

- Mosaki, Nodar (14 March 2012), The Zazas: a kurdish sub-ethnic group or separate people?, zazaki.net, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Nasidze, Ivan; Quinque, Dominique; Ozturk, Murat; Bendukidze, Nina; Stoneking, Mark (2005), "MtDNA and Y-chromosome Variation in Kurdish Groups", Annals of Human Genetics, 69 (4): 401–412, doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2005.00174.x, ISSN 0003-4800, PMID 15996169

- Özoğlu, Hakan (2004), Kurdish notables and the Ottoman state : evolving identities, competing loyalties, and shifting boundaries, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-5993-5

- Postgate (2007), Languages of Iraq, ancient and modern. (PDF), Cambridge: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, ISBN 978-0-903472-21-0, retrieved 20 May 2019

- Sputnik (2019), KONDA'nın anketine göre Türkiye'de kimliğini 'Kürt' olarak açıklayanların oranı yüzde 16 (in Turkish), retrieved 7 June 2020

- Taylor, J. G. (1865), "Travels in Kurdistan, with Notices of the Sources of the Eastern and Western Tigris, and Ancient Ruins in Their Neighbourhood", Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, 35: 21–58, doi:10.2307/3698077, JSTOR 3698077

- van Bruinessen, Martin (1989), The Ethnic Identity of the Kurds in Turkey, pp. 613–621

- Werner, Eberhard (2012), "Considerations about the religions of the Zaza people" (PDF), II. Uluslararası Zaza Tarihi ve Kültürü Sempozyumu (in Zazaki), Bingöl Üniversitesi Yayınları, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Ziflioğlu, Vercihan (23 May 2011), Turkey's Zaza gearing up efforts for recognition of rights, Istanbul, Hürriyet Daily News, archived from the original on 22 June 2015, retrieved 7 June 2020