Hungarians

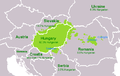

Hungarians, also known as Magyars (Hungarian: magyarok), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary (Hungarian: Magyarország) and historical Hungarian lands who share a common ancestry, culture, history and language. Hungarian belongs to the Uralic language family. There are an estimated 14.2–14.5 million ethnic Hungarians and their descendants worldwide, of whom 9.6 million live in today's Hungary (as of 2016).[1] About 2.2 million Hungarians live in areas that were part of the Kingdom of Hungary before the Treaty of Trianon and are now parts of Hungary's seven neighbouring countries, Slovakia, Ukraine, Romania, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia and Austria. Significant groups of people with Hungarian ancestry live in various other parts of the world, most of them in the United States, Canada, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Australia, and Argentina.

The seven Magyar chieftains arriving to the Carpathian Basin. Detail from Árpád Feszty's cyclorama titled the Arrival of the Hungarians. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 14.2–14.5 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,437,694 (2013)[2] | |

| 1,227,623 (2011)[3] | |

| 458,467 (2011)[4] | |

| 348,085 (2016)[5] | |

| 253,899 (2011)[6] | |

| 156,566 (2001)[7] | |

| 156,812[8] | |

| 100,000–200,000 (2004)[9] | |

| 87,604 (2020)[10] | |

| 80,000[11] | |

| 67,616[12] | |

| 52,250 (2011) | |

| 40,000–70,000 | |

| 50,000–55,000 | |

| 40,000–50,000 | |

| 16,595 (2001)[13] | |

| c. 10,000–200,000[14] | |

| Languages | |

| Hungarian | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity: Roman Catholicism;[15] Protestantism (chiefly Calvinism, Unitarianism and Lutheranism); Greek Catholic; Judaism; Islam; Atheism. | |

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early history

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contemporary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Hungarians can be classified into several subgroups according to local linguistic and cultural characteristics; subgroups with distinct identities include the Székelys, the Csángós, the Palóc and the Matyó. The Jász people are considered to be an originally Iranic ethnic group more closely related to the Ossetians than to other Hungarians.

Name

The Hungarians' own ethnonym to denote themselves in the Early Middle Ages is uncertain. The exonym "Hungarian" is thought to be derived from Oghur-Turkic On-Ogur (literally "Ten Arrows" or "Ten Tribes"). Another possible explanation comes from the Old Russian "Yugra" ("Югра"). It may refer to the Hungarians during a time when they dwelt east of the Ural Mountains along the natural borders of Europe and Asia before their conquest of the Carpathian Basin.[16]

Prior to the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin in 895/6 and while they lived on the steppes of Eastern Europe east of the Carpathian Mountains, written sources called the Magyars "Hungarians", specifically: "Ungri" by Georgius Monachus in 837, "Ungri" by Annales Bertiniani in 862, and "Ungari" by the Annales ex Annalibus Iuvavensibus in 881. The Magyars/Hungarians probably belonged to the Onogur tribal alliance, and it is possible that they became its ethnic majority.[17] In the Early Middle Ages, the Hungarians had many names, including "Węgrzy" (Polish), "Ungherese" (Italian), "Ungar" (German), and "Hungarus".[18] The "H-" prefix is a later addition of Medieval Latin.

The Hungarian people refer to themselves by the demonym "Magyar" rather than "Hungarian".[17] "Magyar" is Finno-Ugric[19] from the Old Hungarian "mogyër". "Magyar" possibly derived from the name of the most prominent Hungarian tribe, the "Megyer". The tribal name "Megyer" became "Magyar" in reference to the Hungarian people as a whole.[20][21][22] "Magyar" may also derive from the Hunnic "Muageris" or "Mugel".[23] According the Hungarian origin myth Hunor and Magor (first appeared in the 13th century chronicle Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum) the name "Magyar" was given after the legendary forefather, Magor.[24]

The Greek cognate of "Tourkia" (Greek: Τουρκία) was used by the scholar and Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII "Porphyrogenitus" in his De Administrando Imperio of c. AD 950,[25][26] though in his use, "Turks" always referred to Magyars.[27] This was a misnomer, as while the Magyars had adopted some Turkic cultural traits, they are not a Turkic people.[28]

The historical Latin phrase "Natio Hungarica" ("Hungarian nation") had a wider and political meaning because it once referred to all nobles of the Kingdom of Hungary, regardless of their ethnicity or mother tongue.[29]

History

Origin

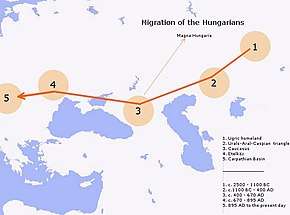

The origin of Hungarians, the place and time of their ethnogenesis, is a matter of debate. Due to the classification of Hungarian as an Ugric language, they are commonly considered an Ugric people that originated from the Ural Mountains, Western Siberia or the Middle Volga region. The relatedness of Hungarians with the Ugric peoples is almost exclusively founded on linguistic data and has been called into question. It is not backed with testimonies in historical sources or the results of natural science research.[30]

"Hungarian pre-history", i.e. the history of the "ancient Hungarians" before their arrival in the Carpathian basin at the end of the 9th century, is thus a "tenuous construct", based on linguistics, analogies in folklore, archaeology and subsequent written evidence. In the 21th century, historians have argued that "Hungarians" did not exist as a discrete ethnic group or people for centuries before their settlement in the Carpathian basin. Instead, the formation of the people with its distinct identity was a process. According to this view, Hungarians as a people emerged by the 9th century, subsequently incorporating other, ethnically and linguistically divergent, peoples.[31]

Pre-4th century AD

During the 4th millennium BC, the Uralic-speaking peoples who were living in the central and southern regions of the Urals split up. Some dispersed towards the west and northwest and came into contact with Iranian speakers who were spreading northwards.[32] From at least 2000 BC onwards, the Ugric-speakers became distinguished from the rest of the Uralic community, of which the ancestors of the Magyars, being located farther south, were the most numerous. Judging by evidence from burial mounds and settlement sites, they interacted with the Indo-Iranian Andronovo culture.[33]

4th century to c. 830

In the 4th and 5th centuries AD, the Hungarians moved from the west of the Ural Mountains to the area between the southern Ural Mountains and the Volga River known as Bashkiria (Bashkortostan) and Perm Krai. In the early 8th century, some of the Hungarians moved to the Don River to an area between the Volga, Don and the Seversky Donets rivers.[34] Meanwhile, the descendants of those Hungarians who stayed in Bashkiria remained there as late as 1241.

The Hungarians around the Don River were subordinates of the Khazar khaganate. Their neighbours were the archaeological Saltov culture, i.e. Bulgars (Proto-Bulgarians, Onogurs) and the Alans, from whom they learned gardening, elements of cattle breeding and of agriculture. Tradition holds that the Hungarians were organized in a confederacy of seven tribes. The names of the seven tribes were: Jenő, Kér, Keszi, Kürt-Gyarmat, Megyer, Nyék, and Tarján.

c. 830 to c. 895

Around 830, a rebellion broke out in the Khazar khaganate. As a result, three Kabar tribes[35] of the Khazars joined the Hungarians and moved to what the Hungarians call the Etelköz, the territory between the Carpathians and the Dnieper River. The Hungarians faced their first attack by the Pechenegs around 854,[34] though other sources state that an attack by Pechenegs was the reason for their departure to Etelköz. The new neighbours of the Hungarians were the Varangians and the eastern Slavs. From 862 onwards, the Hungarians (already referred to as the Ungri) along with their allies, the Kabars, started a series of looting raids from the Etelköz into the Carpathian Basin, mostly against the Eastern Frankish Empire (Germany) and Great Moravia, but also against the Balaton principality and Bulgaria.[36]

Entering the Carpathian Basin (c. 895)

In 895/896, under the leadership of Árpád, some Hungarians crossed the Carpathians and entered the Carpathian Basin. The tribe called Magyar was the leading tribe of the Hungarian alliance that conquered the centre of the basin. At the same time (c. 895), due to their involvement in the 894–896 Bulgaro-Byzantine war, Hungarians in Etelköz were attacked by Bulgaria and then by their old enemies the Pechenegs. The Bulgarians won the decisive battle of Southern Buh. It is uncertain whether or not those conflicts were the cause of the Hungarian departure from Etelköz.

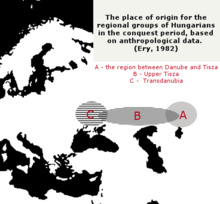

From the upper Tisza region of the Carpathian Basin, the Hungarians intensified their looting raids across continental Europe. In 900, they moved from the upper Tisza river to Transdanubia (Pannonia), which later became the core of the arising Hungarian state. At the time of the Hungarian migration, the land was inhabited only by a sparse population of Slavs, numbering about 200,000,[34] who were either assimilated or enslaved by the Hungarians.[34]

Archaeological findings (e.g. in the Polish city of Przemyśl) suggest that many Hungarians remained to the north of the Carpathians after 895/896.[37] There is also a consistent Hungarian population in Transylvania, the Székelys, who comprise 40% of the Hungarians in Romania.[38][39] The Székely people's origin, and in particular the time of their settlement in Transylvania, is a matter of historical controversy.

After 900

In 907, the Hungarians destroyed a Bavarian army in the Battle of Pressburg and laid the territories of present-day Germany, France, and Italy open to Hungarian raids, which were fast and devastating. The Hungarians defeated the Imperial Army of Louis the Child, son of Arnulf of Carinthia and last legitimate descendant of the German branch of the house of Charlemagne, near Augsburg in 910. From 917 to 925, Hungarians raided through Basle, Alsace, Burgundy, Saxony, and Provence.[40] Hungarian expansion was checked at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955, ending their raids against Western Europe, but raids on the Balkan Peninsula continued until 970.[41]

The Pope approved Hungarian settlement in the area when their leaders converted to Christianity, and Stephen I (Szent István, or Saint Stephen) was crowned King of Hungary in 1001. The century between the arrival of the Hungarians from the eastern European plains and the consolidation of the Kingdom of Hungary in 1001 was dominated by pillaging campaigns across Europe, from Dania (Denmark) to the Iberian Peninsula (contemporary Spain and Portugal).[42] After the acceptance of the nation into Christian Europe under Stephen I, Hungary served as a bulwark against further invasions from the east and south, especially by the Turks.

At this time, the Hungarian nation numbered around 400,000 people.[34]

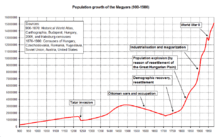

Early modern period

The first accurate measurements of the population of the Kingdom of Hungary including ethnic composition were carried out in 1850–51. There is a debate among Hungarian and non-Hungarian (especially Slovak and Romanian) historians about the possible changes in the ethnic structure of the region throughout history. Some historians support the theory that the proportion of Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin was at an almost constant 80% during the Middle Ages.[43][44][45][46][47] Non-Hungarians numbered hardly more than 20% to 25% of the total population.[43] The Hungarian population began to decrease only at the time of the Ottoman conquest,[43][44][47] reaching as low as around 39% by the end of the 18th century. The decline of the Hungarians was due to the constant wars, Ottoman raids, famines, and plagues during the 150 years of Ottoman rule.[43][44][47] The main zones of war were the territories inhabited by the Hungarians, so the death toll depleted them at a much higher rate than among other nationalities.[43][47] In the 18th century, their proportion declined further because of the influx of new settlers from Europe, especially Slovaks, Serbs and Germans.[48] As a consequence of Turkish occupation and Habsburg colonization policies, the country underwent a great change in ethnic composition as its population more than tripled to 8 million between 1720 and 1787, while only 39% of its people were Hungarians, who lived primarily in the centre of the country.[43][44][45][47]

Other historians, particularly Slovaks and Romanians, argue that the drastic change in the ethnic structure hypothesized by Hungarian historians in fact did not occur. They argue that the Hungarians accounted for only about 30–40% of the Kingdom's population from its establishment. In particular, there is a fierce debate among Hungarians and Romanian historians about the ethnic composition of Transylvania through these times.

19th century to present

In the 19th century, the proportion of Hungarians in the Kingdom of Hungary rose gradually, reaching over 50% by 1900 due to higher natural growth and Magyarization. Between 1787 and 1910 the number of ethnic Hungarians rose from 2.3 million to 10.2 million, accompanied by the resettlement of the Great Hungarian Plain and Voivodina by mainly Roman Catholic Hungarian settlers from the northern and western counties of the Kingdom of Hungary. In 1715 (after the Ottoman occupation), the Southern Great Plain was nearly uninhabited but now has 1.3 million inhabitants, nearly all of them Hungarians.

Spontaneous assimilation was an important factor, especially among the German and Jewish minorities and the citizens of the bigger towns. On the other hand, about 1.5 million people (about two-thirds non-Hungarian) left the Kingdom of Hungary between 1890–1910 to escape from poverty.[49]

.png)

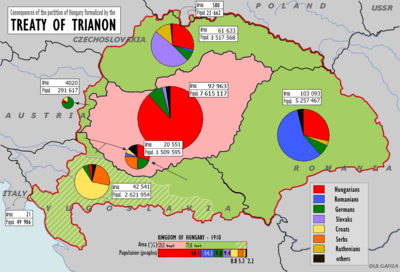

The years 1918 to 1920 were a turning point in the Hungarians' history. By the Treaty of Trianon, the Kingdom had been cut into several parts, leaving only a quarter of its original size. One-third of the Hungarians became minorities in the neighbouring countries.[50] During the remainder of the 20th century, the Hungarians population of Hungary grew from 7.1 million (1920) to around 10.4 million (1980), despite losses during the Second World War and the wave of emigration after the attempted revolution in 1956. The number of Hungarians in the neighbouring countries tended to remain the same or slightly decreased, mostly due to assimilation (sometimes forced; see Slovakization and Romanianization)[51][52][53] and to emigration to Hungary (in the 1990s, especially from Transylvania and Vojvodina).

After the "baby boom" of the 1950s (Ratkó era), a serious demographic crisis began to develop in Hungary and its neighbours.[54] The Hungarian population reached its maximum in 1980, then began to decline.[54]

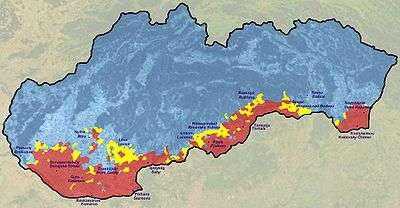

For historical reasons (see Treaty of Trianon), significant Hungarian minority populations can be found in the surrounding countries, most of them in Romania (in Transylvania), Slovakia, and Serbia (in Vojvodina). Sizable minorities live also in Ukraine (in Transcarpathia), Croatia (primarily Slavonia), and Austria (in Burgenland). Slovenia is also host to a number of ethnic Hungarians, and Hungarian language has an official status in parts of the Prekmurje region. Today more than two million ethnic Hungarians live in nearby countries.[55]

There was a referendum in Hungary in December 2004 on whether to grant Hungarian citizenship to Hungarians living outside Hungary's borders (i.e. without requiring a permanent residence in Hungary). The referendum failed due to insufficient voter turnout. On 26 May 2010, Hungary's Parliament passed a bill granting dual citizenship to ethnic Hungarians living outside of Hungary. Some neighboring countries with sizable Hungarian minorities expressed concerns over the legislation.[56]

Ethnic affiliations and genetic origins

Thanks to Pál Lipták's research it has been known for almost half a century that only 16.7 percent of 10th-century human bones belong to the Euro-Mongoloid and Mongoloid types.[57][58] The European characteristics in the biological composition of the recent Hungarian population and the lack of Asian markers are not solely due to the thousand years of blending.[57] The population around 1000 AD in Hungary was made up almost exclusively of people who were genetically Europid.[57]

According to a 2008 publication from the European Journal of Human Genetics, the Y-DNA haplogroup Haplogroup R1a1a-M17 was found amongst 57% of modern Hungarian male samples, genetically clustering them with that of their neighboring West Slavic neighbors, the Czechs, Poles, and Slovaks.[59] Another study on Y-Chromosome markers concluded that "modern Hungarian and Székelys (a subgroup of Hungarians living in the Székely Land in modern-day central Romania) are genetically related, and that they share similar components described for other Europeans, except for the presence of the Haplogroup P (M173) in Székely samples, which may reflect a Central Asian connection from the time of the Hungarian migration from the Urals to Europe.[60]

Recent genetic research is in line with the previous archaeological and anthropological assumptions that the original Hungarian conqueror tribes were related to the Onogur-Bulgars.[61] A substantial part of the conquerors show similarities to the Xiongnu and Asian Scythians and presumably this Inner Asian component on their way to Europe mixed with the peoples of the Pontic steppes. According to this study the conqueror Hungarians owed their mostly Europid characteristics to the descendants of the Srubnaya culture.[61]

Neparáczki argues, based on new archeogenetic results, that the Conqueror Hungarians were mostly a mixture of Hunnic, Slavic, and Germanic tribes having comparable proportion of European and Asian origin and this composite people evolved in the steppes of Eastern Europe between 400 and 1000 AD.[62][63] His research group also established that "genetic continuity can be detected between ancient and modern Hungarians"[64] and "genetic heritage of the Conquerors definitely persists in modern Hungarians" in almost 1/8th of recent Hungarian gene pool.[65] According to Neparáczki: "From all recent and archaic populations tested the Volga Tatars show the smallest genetic distance to the entire Conqueror population" and "a direct genetic relation of the Conquerors to Onogur-Bulgar ancestors of these groups is very feasible."[65]

Another study on Y-Chromosome markers concluded that "modern Hungarian and Székely populations are genetically closely related", and that they "share similar components described for other Europeans, except for the presence of the haplogroup P*(xM173) in Székely samples, which may reflect a Central Asian connection, and high frequency of haplogroup J in both Székelys and Hungarians".[66] The subclade of Haplogroup N, which is N-L1034 and a Uralic link, is shared by 4% of the Székely Hungarians and 15% of the closest language relatives the Mansis.[65]

A 2007 study on the mtDNA, after precising that "Hungarians are unique among the other European populations because according to history the ancient Magyars had come from the eastern side of the Ural Mountains and settled down in the Carpathian basin in the 9th century AD", shows that the haplogroup M, "characteristic mainly for Asian populations", is "found in approximately 5% of the total", which thus "suggests that an Asian matrilineal ancestry, even if in a small incidence, can be detected among modern Hungarians."[67]

According to a 2008 study, the mitochondrial lines of the modern Hungarians are indistinct from that of neighbouring West Slavs, but they are distinct from that of the ancient Hungarians (Magyars). Four 10th century skeletons from well documented cemeteries in Hungary of ancient Magyar individuals were sampled.[68] Two of the four males belonged to Y-DNA Haplogroup N confirming their Uralic origin. None out of 100 sampled modern Hungarians carried the haplogroup, and just one of about 94 Székelys carried it. The study also stated that it was possible that the more numerous pre-existing populations or substantional later migrations, mostly Avars and Slavs, accepted the Uralic language of the elite.[68]

Another genetic research have shown that the first-generation Magyar core gene pool originated in Central Asia/South Siberia and, as Magyars were moving westward, admixing with additional strata of people of European origin, and people of the Caucasus. Burial samples of the Karos-Eperjesszög Magyars place them genetically closest to Turkic peoples, modern south Caucasian peoples, and modern Western Europeans to a limited degree, while no specific Finno-Ugric markers were found.[69] However, a 2008 study done on 10th century Magyar skeletons, indeed found a few Uralic samples.[68]

An autosomal analysis,[70] studying non-European admixture in Europeans, found 4.4% of admixture of non-European and non-Middle Eastern origin among Hungarians, which was the strongest among sampled populations. It was found at 3.6% in Belarusians, 2.5% in Romanians, 2.3% in Bulgarians and Lithuanians, 1.9% in Poles and 0% in Greeks. The authors stated "This signal might correspond to a small genetic legacy from invasions of peoples from the Asian steppes (e.g., the Huns, Magyars, and Bulgars) during the first millennium CE.".

Compared to the European nations, Andrea Vágó-Zalán's study determined that the Bulgarians were genetically the closest and the Estonians and Finns were among the furthest from the recent Hungarian population.[71]

Anthropologically, the type of Magyars of the conquest phase shows similarities with modern Central Asians. The "Turanid" (South-Siberian) and the "Uralid" types from the Europid-Mongoloid admixture were dominant among the conquering Hungarians.[72]

A recent study from 2018 shows that ancient samples of both Magyars and Avars can clearly be linked to several Mongoloid groups of East Asia and Siberia. The samples are most closely related to populations in modern Mongolia and Northern China. The scientists suggest that modern groups like Yakuts or Tungusic peoples share a close relation to ancient Hungarians and Avars.[73]

Paternal haplogroups

According to Pamjav Horolma's study, which is based on 230 samples and expected to include 6-8% Gypsy peoples, the small Hungarian haplogroup distribution study from Hungary is as follows: 26% R1a, 20% I2a, 19% R1b, 7% I, 6% J2, 5% H, 5% G2a, 5% E1b1b1a1, 3% J1, <1% N, <1% R2.[74] According to another study by Pamjav, the area of Bodrogköz suggested to be a population isolate found an elevated frequency of Haplogroup N: R1a-M458 (20.4%), I2a1-P37 (19%), R1a-Z280 (14.3%), and E1b-M78 (10.2%). Various R1b-M343 subgroups accounted for 15% of the Bodrogköz population. Haplogroup N1c-Tat covered 6.2% of the lineages, but most of it belonged to the N1c-VL29 subgroup, which is more frequent among Balto-Slavic speaking than Finno-Ugric speaking peoples. Other haplogroups had frequencies of less than 5%.[75][76]

Among 100 Hungarian men, 90 of whom from the Great Hungarian Plain, the following haplogroups and frequencies are obtained: 30% R1a, 15% R1b, 13% I2a1, 13% J2, 9% E1b1b1a, 8% I1, 3% G2, 3% J1, 3% I*, 1% E*, 1% F*, 1% K*. The 97 Székelys belong to the following haplogroups: 20% R1b, 19% R1a, 17% I1, 11% J2, 10% J1, 8% E1b1b1a, 5% I2a1, 5% G2, 3% P*, 1% E*, 1% N.[77] It can be inferred that Szekelys have more significant German admixture. A study sampling 45 Palóc from Budapest and northern Hungary, found 60% R1a, 13% R1b, 11% I, 9% E, 2% G, 2% J2.[78] A study estimating possible Inner Asian admixture among nearly 500 Hungarians based on paternal lineages only, estimated it at 5.1% in Hungary, at 7.4 in Székelys and at 6.3% at Csangos.[79] It has boldly been noted that this is an upper limit by deep SNPs and that the main haplogroups responsible for that contribution are J2-M172 (negative M47, M67, L24, M12), J2-L24, R1a-Z93, Q-M242 and E-M78, the latter of which is typically European, while N is still negligible (1.7%). In an attempt to divide N into subgroups L1034 and L708, some Hungarian, Székely, and Uzbek samples were found to be L1034 SNP positive, while all Mongolians, Buryats, Khanty, Finnish, and Roma samples showed a negative result for this marker. The 2500 years old SNP L1034 was found typical for Mansi and Hungarians, the closest linguistic relatives.[80]

The following information is inferred from 433 Hungarian samples from the Hungarian Magyar Y-DNA Project in Family Tree (29 May 2017):[81]

- 26.1% R1a (15% Z280, 6.5% M458, 0.9% Z93=>S23201 "Altai/Tian Shan", 3.7% unknown)

- 19.2% R1b (6% L11-P312/U106, 5.3% P312, 4.2% L23/Z2103, 3.7% U106)

- 16.9% I2 (15.2% CTS10228, 1.4% M223, 0.5% L38)

- 8.3% I1

- 8.1% J2 (5.3% M410, 2.8% M102)

- 6.9% E1b1b1 (6% V13, 0.3% V22, 0.3% M123, 0.3% M81)

- 6.9% G2a

- 3.2% N (1.4% Z1936 "Ugric/Proto-Magyar", 0.5% M2019/VL67 "Siberia and Baykal", 0.5% Y7310 "Central Europe", 0.9% Z16981 "Baltic")- note: only unrelated males are sampled

- 2.3% Q (1.2% YP789 "Huns/Turkmens", 0.9% M346 "Siberia", 0.2% M242 "Xiongnu")

- 0.9% T

- 0.5% J1

- 0.2% L

- 0.2% C

Other influences

Besides the various peoples mentioned above, the Magyars later were influenced by other populations in the Carpathian Basin. Among these are the Cumans, Pechenegs, Jazones, West Slavs, Germans and Vlachs (Romanians). Ottomans, who occupied the central part of Hungary from c. 1526 until c. 1699, inevitably exerted an influence, as did the various nations (Germans, Slovaks, Serbs, Croats, and others) that resettled depopulated territories after their departure. Similar to other European countries, Jewish, Armenian and Roma (Gypsy) ethnic minorities have been living in Hungary since the Middle Ages.

Hungarian diaspora

Hungarian diaspora (Magyar diaspora) is a term that encompasses the total ethnic Hungarian population located outside of current-day Hungary.

Hungarians in Romania (according to the 2002 census)

Hungarians in Romania (according to the 2002 census) Hungarians in Vojvodina, Serbia (according to the 2011 census)

Hungarians in Vojvodina, Serbia (according to the 2011 census) Hungarians in Slovakia (according to the 2001 census)

Hungarians in Slovakia (according to the 2001 census) Hungarians in Ukraine (according to the 2001 census)

Hungarians in Ukraine (according to the 2001 census) Hungarians in the United States (according to the 2000 census)

Hungarians in the United States (according to the 2000 census)

Maps

Kniezsa's (1938) view on the ethnic map of the Kingdom of Hungary in the 11th century, based on toponyms. Kniezsa's view has been criticized by many scholars, because of its non-compliance with later archaeological and onomastics research, but his map is still regularly cited in modern reliable sources.[under discussion]

Kniezsa's (1938) view on the ethnic map of the Kingdom of Hungary in the 11th century, based on toponyms. Kniezsa's view has been criticized by many scholars, because of its non-compliance with later archaeological and onomastics research, but his map is still regularly cited in modern reliable sources.[under discussion] The "Red Map", based on the controversial 1910 census (peak of the magyarization): Hungarians in the Kingdom of Hungary

The "Red Map", based on the controversial 1910 census (peak of the magyarization): Hungarians in the Kingdom of Hungary Regions where Hungarian is spoken

Regions where Hungarian is spoken

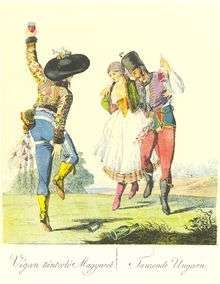

Traditional costumes (18th and 19th century)

Folklore and communities

Hungarians dressed in folk costumes in Southern Transdanubia, Hungary

Hungarians dressed in folk costumes in Southern Transdanubia, Hungary Vojvodina Hungarians women's national costume

Vojvodina Hungarians women's national costume Kalotaszeg folk Costume in Transylvania, Romania

Kalotaszeg folk Costume in Transylvania, Romania The Hungarian Puszta

The Hungarian Puszta The Turul, the mythical bird of Hungary

The Turul, the mythical bird of Hungary

See also

- Central Europe

- Demographics of Hungary

- List of Hungarians

- List of people of Hungarian origin

- Ugric languages

- Khanty people

- Mansi people

- Eastern Magyars

- Magyarab people

- Jász people

- Székelys of Bukovina

- Kunság

- Pole, Hungarian, two good friends

- Hungarian mythology

- Hunor and Magor

- Shamanistic remnants in Hungarian folklore

- List of domesticated animals from Hungary

Notes

- This number is a lower estimate, as 405,261 people (7.5% of the total population) did not specify their ethnicity at the 2011 Slovak Census.

References

- Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 - 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus - 12. Ethnic data] (PDF). Hungarian Central Statistical Office (in Hungarian). Budapest. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- "Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported: 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. 2013. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- (in Romanian) "Comunicat de presă privind rezultatele definitive ale Recensământului Populaţiei şi Locuinţelor – 2011", at the 2011 Romanian census site; accessed 11 July 2013

- 2001 Slovakian Census

- "The 2006 census". 2.statcan.ca. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- 2011 Serbian Census

- "About number and composition population of UKRAINE by data All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. 2003. Archived from the original on 31 October 2004.

- "Anzahl der Ausländer in Deutschland nach Herkunftsland (Stand: 31. Dezember 2014)". De.statista.com. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Bund Ungarischer Organisationen in Deutschland" [Confederation of Hungarian Organizations in Germany]. buod.de (in German). Archived from the original on 6 February 2006.

- "Bevölkerung zu Jahresbeginn 2002-2020 nach detaillierter Staatsangehörigkeit" [Population at the beginning of the year 2002-2020 by detailed nationality] (PDF). Statistics Austria (in German). 12 February 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Moschella, Alexandre (24 June 2002). "Um atalho para a Europa" [A shortcut to Europe] (in Portuguese). Revista Época Edição. Archived from the original on 27 February 2003.

- "Australian Bureau of Statistics (Census 2006)". Abs.gov.au. 3 April 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Položaj nacionalnih manjina u Republici Hrvatskoj – zakonodavstvo i praksa" [The Position of National Minorities in the Republic of Croatia - Legislation and Practice] (in Croatian). Centre for Human Rights. April 2005. Archived from the original on 16 May 2007.

- https://epa.oszk.hu/00400/00462/00048/1890.htm

- Discrimination in the EU in 2012 (PDF). Special Eurobarometer (Report). 383. European Commission. November 2012. p. 233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2013. The question asked was "Do you consider yourself to be...?" With a card showing: Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, Other Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu, Atheist, and Non-believer/Agnostic. Space was given for Other (SPONTANEOUS) and DK. Jewish, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu did not reach the 1% threshold.

- OED, s. v. "Ugrian": "Ugri, the name given by early Russian writers to a Finno-Ugric people dwelling east of the Ural Mountains".

- Peter F. Sugar, ed. (22 November 1990). A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-253-20867-5. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- Edward Luttwak, The grand strategy of the Byzantine Empire, Harvard University Press, 2009, p. 156

- Robert B Kaplan, Ph.D., Richard B Baldauf, Jr., Language Planning And Policy In Europe: Finland, Hungary And Sweden, Multilingual Matters, 2005, p. 28

- György Balázs, Károly Szelényi, The Magyars: the birth of a European nation, Corvina, 1989, p. 8

- Alan W. Ertl, Toward an Understanding of Europe: A Political Economic Précis of Continental Integration, Universal-Publishers, 2008, p. 358

- Z. J. Kosztolnyik, Hungary under the early Árpáds: 890s to 1063, Eastern European Monographs, 2002, p. 3

- "Magyar őstörténeti tanulmányok. Szerk. Schütz Ödön. (Budapest Oriental Reprints, Ser. A 3.) | Könyvtár | Hungaricana". library.hungaricana.hu.

- Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 1.4–5), pp. 13–17.

- Jenkins, Romilly James Heald (1967). De Administrando Imperio by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus. Corpus fontium historiae Byzantinae (New, revised ed.). Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-88402-021-9. Retrieved 28 August 2013. According to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, writing in his De Administrando Imperio (c. AD 950), "Patzinakia, the Pecheneg realm, stretches west as far as the Siret River (or even the Eastern Carpathian Mountains), and is four days distant from Tourkia (i.e. Hungary)."

- Günter Prinzing; Maciej Salamon (1999). Byzanz und Ostmitteleuropa 950-1453: Beiträge zu einer table-ronde des XIX. International Congress of Byzantine Studies, Copenhagen 1996. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-447-04146-1. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Henry Hoyle Howorth (2008). History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century: The So-called Tartars of Russia and Central Asia. Cosimo, Inc. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-60520-134-4. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- A MAGYAROK TÜRK MEGNEVEZÉSE BÍBORBANSZÜLETETT KONSTANTINOS DE ADMINISTRANDOIMPERIO CÍMÛ MUNKÁJÁBAN - Takács Zoltán Bálint, SAVARIAA VAS MEGYEI MÚZEUMOK ÉRTESÍTÕJE28 SZOMBATHELY, 2004, pp. 317–333

- http://www.hungarianhistory.com/lib/transy/transy05.htm

- Obrusánszky, Borbála (2018). Angela Marcantonio (ed.). Are the Hungarians Ugric? (PDF). The state of the art of Uralic studies: tradition vs innovation. Sapienza Università Editrice. pp. 87–106, at p. 87–88.

- Nora Berend; Przemysław Urbańczyk; Przemysław Wiszewski (2013). "Hungarian 'pre-history' or 'ethnogenesis'?". Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c.900–c.1300. Cambridge University Press. p. 62.

- Róna-Tas, András (1999). "Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages": 96. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Blench, Roger; Matthew Briggs (1999). Archaeology and Language. Routledge. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-415-11761-6. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "Early History". A Country Study: Hungary. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 29 October 2004. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- Peter F. Sugar, Péter Hanák, Tibor Frank, A History of Hungary, Indiana University Press, 1994 page 11. Google Books

- "Magyars". Thenagain.info. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- Koperski, A.: Przemyśl (Lengyelország). In: A honfoglaló magyarság. Kiállítási katalógus. Bp. 1996. pp. 439–448.

- Piotr Eberhardt (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe. M. E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY and London, England, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5.

- "Szekler people". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Stephen Wyley. "The Hungarians of Hungary". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "History of Hungary, 895–970". Zum.de. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "The Hungarians (650–997 AD)". Fanaticus.org. 22 October 2004. Archived from the original on 7 June 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- Hungary. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 11 May 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- A Country Study: Hungary. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- "International Boundary Study – No. 47 – April 15, 1965 – Hungary – Romania (Rumania) Boundary" (PDF). US Bureau of Intelligence and Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2015.

- Historical World Atlas. With the commendation of the Royal Geographical Society. Carthographia, Budapest, Hungary, 2005. ISBN 978-963-352-002-4 CM

- Steven W. Sowards. "Twenty-Five Lectures on Modern Balkan History (The Balkans in the Age of Nationalism), Lecture 4: Hungary and the limits of Habsburg authority". Michigan State University Libraries. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- Macartney, Carlile Aylmer (1962), "5. The Eighteenth Century", Hungary; A short history, University Press, retrieved 3 August 2016

- Lee, Jonathan; Robert Siemborski. "Peaks/waves of immigration". bergen.org. Archived from the original on 16 June 1997.

- Kocsis, Károly (1998). "Introduction". Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin. Simon Publications LLC. ISBN 978-1-931313-75-9. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- Bugajski, Janusz (1995). Ethnic Politics in Eastern Europe: A Guide to Nationality Policies, Organizations, and Parties. M.E. Sharpe (Washington, D.C.). ISBN 978-1-56324-283-0.

- Kovrig, Bennett (2000), Partitioned nation: Hungarian minorities in Central Europe, in: Michael Mandelbaum (ed.), The new European Diasporas: National Minorities and Conflict in Eastern Europe, New York City: Council on Foreign Relations Press, pp. 19–80.

- Raffay Ernő: A vajdaságoktól a birodalomig. Az újkori Románia története (From voivodeships to the empire. The modern history of Romania). Publishing house JATE Kiadó, Szeged, 1989, pp. 155–156)

- "Nyolcmillió lehet a magyar népesség 2050-re". origo. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- Hungary: Transit Country Between East and West. Migration Information Source. November 2003.

- Veronika Gulyas (26 May 2010). "Hungary Citizenship Bill Irks Neighbor". The Wall Street Journal.

- Csanád Bálint (October 2008). "A történeti genetika és az eredetkérdés(ek)". Magyar Tudomány: 1170. Retrieved 6 October 2009. Cited: "Lipták Pálnak köszönhetően közel fél évszázada tudjuk, hogy a 10. sz.-i embercsontoknak csak 16,7 %-a tartozik a mongolid és az europo-mongolid rasszhoz. Tehát a mai magyarság szerológiai, és genetikai összetételében egyértelműen kimutatott európai jelleg, ugyanakkor az ázsiainak hiánya nem egyedül az eltelt ezer év keveredéseinek köszönhető, hanem már a honfoglalás- és Szent István-kori Magyarország lakossága is szinte kizárólag biológiailag európai eredetűekből állt." Translation: "Due to Pál Lipták we have known for almost half a century that only 16.7 percent of 10th-century human bones belong to the Euro-Mongoloid and Mongoloid races. Thus, the unambiguously established European characteristics in the genetic and serological composition of the recent Hungarian population and the lack of Asian markers are not solely due to the thousand years of blending but biologically the populations of the conquest period and of St Stephen's Hungary were made up almost exclusively of peoples of European origin."

- Pál Lipták: A magyarság etnogenezisének paleoantropológiája (The paleoanthropology of Hungarian people's ethnogenesis) (Antropológiai Közl., 1970. 14. sz.)

- Battaglia, Vincenza; Fornarino, Simona; Al-Zahery, Nadia; Olivieri, Anna; Pala, Maria; Myres, Natalie M; King, Roy J; Rootsi, Siiri; Marjanovic, Damir (2009). "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 820–830. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249. ISSN 1018-4813. PMC 2947100. PMID 19107149.

- Csányi, B.; Bogácsi-Szabó, E.; Tömöry, Gy.; Czibula, Á.; Priskin, K.; Csõsz, A.; Mende, B.; Langó, P.; Csete, K.; Zsolnai, A.; Conant, E. K.; Downes, C. S.; Raskó, I. (2008). "Y-Chromosome Analysis of Ancient Hungarian and Two Modern Hungarian-Speaking Populations from the Carpathian Basin". Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (4): 519–534. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00440.x. ISSN 0003-4800. PMID 18373723.

- Török, Tibor; Zink, Albert; Raskó, István; Pálfi, György; Kustár, Ágnes; Pap, Ildikó; Fóthi, Erzsébet; Nagy, István; Bihari, Péter (18 October 2018). "Mitogenomic data indicate admixture components of Central-Inner Asian and Srubnaya origin in the conquering Hungarians". PLOS One. 13 (10): e0205920. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1305920N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205920. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6193700. PMID 30335830.

- Endre Neparacki, A honfoglalók genetikai származásának és rokonsági viszonyainak vizsgálata archeogenetikai módszerekkel, ELTE TTK Biológia Doktori Iskola, 2017, pp. 61-65

- Neparáczki, E.; et al. (2016). "Revising mtDNA haplotypes of the ancient Hungarian conquerors with next generation sequencing". bioRxiv 10.1101/092239.

- Neparáczki, Endre; Juhász, Zoltán; Pamjav, Horolma; Fehér, Tibor; Csányi, Bernadett; Zink, Albert; Maixner, Frank; Pálfi, György; Molnár, Erika; Pap, Ildikó; Kustár, Ágnes; Révész, László; Raskó, István; Török, Tibor (2017). "Genetic structure of the early Hungarian conquerors inferred from mtDNA haplotypes and Y-chromosome haplogroups in a small cemetery" (PDF). Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 292 (1): 201–214. doi:10.1007/s00438-016-1267-z. PMID 27803981. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- Neparaczki, Endre; Maroti, Zoltan; Kalmar, Tibor; Kocsy, Klaudia; Maar, Kitti; Bihari, Peter; Nagy, Istvan; Fothi, Erzsebet; Pap, Ildiko; Kustar, Agnes; Palfi, Gyorgy; Rasko, Istvan; Zink, Albert; Torok, Tibor (19 January 2018). "Mitogenomic data indicate admixture components of Asian Hun and Srubnaya origin in the Hungarian Conquerors". bioRxiv: 250688. doi:10.1101/250688.

- Csányi, B.; Bogácsi-Szabó, E.; Tömöry, Gy.; Czibula, Á.; Priskin, K.; Csõsz, A.; Mende, B.; Langó, P.; Csete, K.; Zsolnai, A.; Conant, E. K.; Downes, C. S.; Raskó, I. (2008). "Y-Chromosome Analysis of Ancient Hungarian and Two Modern Hungarian-Speaking Populations from the Carpathian Basin". Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (4): 519–534. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00440.x. ISSN 0003-4800. PMID 18373723.

- Nadasi E. ; Gyurus P. ; Czakó M. ; Bene J. ; Kosztolányi S. ; Fazekas S. ; Dömösi P. ; Melegh B. (2007). "Comparison of mtDNA haplogroups in Hungarians with four other European populations: a small incidence of descents with Asian origin.". Acta Biol Hung. Jun;58(2):245-56

- Csányi, B.; Bogácsi-Szabó, E.; Tömöry, Gy.; Czibula, Á.; Priskin, K.; Csõsz, A.; Mende, B.; Langó, P.; Csete, K.; Zsolnai, A.; Conant, E. K.; Downes, C. S.; Raskó, I. (1 July 2008). "Y-Chromosome Analysis of Ancient Hungarian and Two Modern Hungarian-Speaking Populations from the Carpathian Basin". Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (4): 519–534. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00440.x. ISSN 1469-1809. PMID 18373723.

- Juhász, Pamjav, Fehér, Csányi, Zink, Maixner, Pálfi, Molnár, Pap, Kustár, Révész, Raskó, Török (July 15, 2016). "Genetic structure of the early Hungarian conquerors inferred from mtDNA haplotypes and Y‑chromosome haplogroups in a small cemetery]." (PDF Archived 2018-07-19 at the Wayback Machine) Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/s00438-016-1267-z

- Science, 14 February 2014, Vol. 343 no. 6172, p. 751, A Genetic Atlas of Human Admixture History, Garrett Hellenthal at al.: "CIs. for the admixture time(s) overlap but predate the Mongol empire, with estimates from 440 to 1080 CE (Fig.3.) In each population, one source group has at least some ancestry related to Northeast Asians, with ~2 to 4% of these groups total ancestry linking directly to East Asia. This signal might correspond to a small genetic legacy from invasions of peoples from the Asian steppes (e.g., the Huns, Magyars, and Bulgars) during the first millennium CE."

- Andrea Vágó-Zalán, A magyar populáció genetikai elemzése nemi kromoszómális markerek alapján, ELTE TTK Biológia Doktori Iskola, 2012, p. 51

- Fóthi, Erzsébet (2000). "Anthropological conclusions of the study of Roman and Migration periods" (PDF). Acta Biologica Szegediensis. 44 (1–4): 87–94. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- Török, Tibor; Zink, Albert; Raskó, István; Pálfi, György; Kustár, Ágnes; Pap, Ildikó; Fóthi, Erzsébet; Nagy, István; Bihari, Péter (2018-10-18). "Mitogenomic data indicate admixture components of Central-Inner Asian and Srubnaya origin in the conquering Hungarians". PLOS ONE. 13 (10): e0205920. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1305920N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205920. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6193700. PMID 30335830.

- "Genetic Structure of the Paternal Lineage of the Roma People (PDF Download Available)". ResearchGate. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- Pamjav, Horolma; Fóthi, Á; Fehér, T.; Fóthi, Erzsébet (13 April 2017). "A study of the Bodrogköz population in north-eastern Hungary by Y chromosomal haplotypes and haplogroups". Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 292 (4): 883–894. doi:10.1007/s00438-017-1319-z. PMID 28409264.

- Pamjav, Horolma; Fóthi, Á.; Fehér, T.; Fóthi, Erzsébet (13 April 2017). "A study of the Bodrogköz population in north-eastern Hungary by Y chromosomal haplotypes and haplogroups". Molecular Genetics and Genomics (XLS)

|format=requires|url=(help). 292 (4): 883–894. doi:10.1007/s00438-017-1319-z. ISSN 1617-4615. PMID 28409264. - Csányi, B.; Bogácsi-Szabó, E.; Tömöry, Gy.; Czibula, Á.; Priskin, K.; Csõsz, A.; Mende, B.; Langó, P.; Csete, K.; Zsolnai, A.; Conant, E. K.; Downes, C. S.; Raskó, I. (1 July 2008). "Y-Chromosome Analysis of Ancient Hungarian and Two Modern Hungarian-Speaking Populations from the Carpathian Basin". Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (4): 519–534. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00440.x. PMID 18373723.

- Semino 2000 et al

- "Testing Central and Inner Asian admixture among contemporary Hungarians (PDF Download Available)". ResearchGate. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- A limited genetic link between Mansi and Hungarians

- "Family Tree DNA - Hungarian_Magyar_Y-DNA_Project". Familytreedna.com. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- A nyelv és a nyelvek ("Language and languages"), edited by István Kenesei. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 2004, ISBN 963-05-7959-6, p. 134)

Sources

- Molnar, Miklos (2001). A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge Concise Histories (Fifth printing 2008 ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66736-4.

- Korai Magyar Történeti Lexicon (9–14. század) (Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th Centuries)) Budapest, Akadémiai Kiadó; 753. ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

- Károly Kocsis (DSc, University of Miskolc) – Zsolt Bottlik (PhD, Budapest University) – Patrik Tátrai: Etnikai térfolyamatok a Kárpát-medence határon túli régióiban + CD (for detailed data), Magyar Tudományos Akadémia (Hungarian Academy of Sciences) – Földrajtudományi Kutatóintézet (Academy of Geographical Studies); Budapest; 2006.; ISBN 963-9545-10-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hungarians. |

- Origins of the Hungarians from the Enciklopédia Humana (with many maps and pictures)

- Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin

- Hungary and the Council of Europe

- Facts about Hungary

- The origin of Hungarians from the Hungarian conquest to Christianity

Genetic studies

- MtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms in Hungary: inferences from the Palaeolithic, Neolithic and Uralic influences on the modern Hungarian gene pool

- Guglielmino, CR; De Silvestri, A; Beres, J (March 2000). "Probable ancestors of Hungarian ethnic groups: an admixture analysis". Annals of Human Genetics. 64 (Pt 2): 145–59. doi:10.1017/S0003480000008010. PMID 11246468.

- Human Chromosomal Polymorphism in a Hungarian Sample

- Hungarian genetics researches 2008–2009 (in Hungarian)