Tatar confederation

Tatar (Old Turkic: 𐱃𐱃𐰺, romanized: Tatar; Mongolian: Татар) was one of the five major tribal confederations (khanlig) in the Mongolian Plateau in the 12th century.

Tatar Nine Tatars Татарын ханлиг | |

|---|---|

| 8th century–1202 | |

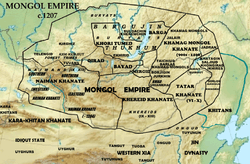

Tatar and their neighbours in the 13th century. | |

| Status | nomadic confederation |

| Religion | Shamanism |

| Government | Elective monarchy |

| chief | |

| Legislature | Kurultai |

| Historical era | High Middle Ages |

• Established | 8th century |

• Disestablished | 1202 |

| Today part of | Mongolia China |

The name "Tatar" was first transliterated in Book of Song as 大檀 Dàtán (MC: *daH-dan) and 檀檀 Tántán (MC: *dan-dan)[1] as other names of the Rourans,[2] who were of Proto-Mongolic Donghu ancestry.[3][4] Songshu and Liangshu connected Rourans to the earlier Xiongnu while Weishu traced the Rouran's origins back to the Donghu.[5] Xu proposed that "the main body of the Rouran were of Xiongnu origin" and Rourans' descendants, namely Da Shiwei (aka Tatars), contained Turkic elements, besides Mongolic Xianbei.[6] Even so, the Xiongnu's language is still unknown,[7] and Chinese historians routinely ascribed Xiongnu origins to various nomadic groups, yet such ascriptions do not necessarity indicate the subjects' exact origins: for examples, Xiongnu ancestry was ascribed to Turkic-speaking Göktürks and Tiele as well as Para-Mongolic-speaking Kumo Xi and Khitans.[8]

The first precise transcription of the Tatar ethnonym was on the Orkhon inscriptions, specifically, the Kul Tigin (CE 732) and Bilge Khagan (CE 735) monuments as 𐰆𐱃𐰔⁚𐱃𐱃𐰺⁚𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣, Otuz Tatar Bodun, ''Thirty Tatar' clan'[9] and 𐱃𐰸𐰔⁚𐱃𐱃𐰺, Tuquz Tatar, 'Nine Tatar'[10][11][12][13] referring to the Tatar confederation. Subsequently, the wider region was referred to by Europeans as "Tartary" or "Tartaria".

The Tatars' Rouran ancestors inhabited the north-eastern Gobi in the 5th century and founded the Rouran Khaganate. Among the Rourans' subjects were the Ashina tribe, who overthrew their Rouran overlords. One branch of the dispersed Rourans migrated to Greater Khingan mountain range where they renamed themselves after Tantan, a historical Khagan, and gradually incorporated themselves into the Shiwei tribal complex and emerged as 大室韋 Da (Great) Shiwei.[14] Later Göktürks acknowledged Tatars as formidable enemies. By the 10th century, Tatars became subjects of the Khitan Liao dynasty. After the fall of the Liao, the Tatars experienced pressure from the Jurchen Jin dynasty and were urged to fight against the other Mongol tribes. The Tatars lived on the fertile pastures around Hulun Nuur and Buir Nuur and occupied a trade route to China in the 12th century. Kara-khanid scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari noted that the Tatars are bilingual, speaking Turkic alongside their own language.[15]

The Tatars were subjugated by Mongol leader Temujin, who subsequently, as Genghis Khan, founded the Mongol Empire. Under the leadership of his grandson Batu Khan, Tatars accompanied Mongols westwards, driving with them many of the Turkic peoples toward the plains of Russia in the Turkic migrations.

Their name Tatar was used by Russians and Europeans to denote Mongols as well as Turkic peoples under Mongol rule, especially in the Golden Horde. Later, it was used for any Turkic or even Mongolic speaking people encountered by Russians. Eventually however, the name stuck onto the Turkic Muslims of Ukraine and Russia, namely, the descendants of Muslim Volga Bulgars, Kipchaks, and Cumans, and Turkicized Mongols or Turko-Mongols (Nogais), as well as other Turkic speaking peoples (Siberian Tatars, Qasim Tatars, Mishar Tatars).

References

- Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 54-56.

- Songshu vol. 95. "芮芮一號大檀,又號檀檀" tr. "Ruìruì, one appellation is Dàtán, also called Tántán"

- Weishu vol. 103 "蠕蠕,東胡之苗裔也,姓郁久閭氏。" tr. "Rúrú, offsprings of Dōnghú, surnamed Yùjiŭlǘ""

-

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Ji 姬 and Jiang 姜: The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity", Early China. p. 20

- Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). pp. 54-55.

- Xu Elina-Qian, Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan, University of Helsinki, 2005. p. 179-180

- Lee, Joo-Yup (2016). "The Historical Meaning of the Term Turk and the Nature of the Turkic Identity of the Chinggisid and Timurid Elites in Post-Mongol Central Asia". Central Asiatic Journal 59(1-2): 116.

It is not known which language the Xiongnu spoke.

- Lee, Joo-Yup (2016). "The Historical Meaning of the Term Turk and the Nature of the Turkic Identity of the Chinggisid and Timurid Elites in Post-Mongol Central Asia". Central Asiatic Journal 59(1-2): 105.

- "Kül Tiğin (Gültekin) Yazıtı Tam Metni (Full text of Kul Tigin monument with Turkish transcription)". Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- "Bilge Kağan Yazıtı Tam Metni (Full text of Bilge Khagan monument with Turkish transcription)". Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- "The Kultegin's Memorial Complex". Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- Ross, E. Denison; Vilhelm Thomsen. "The Orkhon Inscriptions: Being a Translation of Professor Vilhelm Thomsen's Final Danish Rendering". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 5 (4, 1930): 861–876. JSTOR 607024.

- Thomsen, Vilhelm Ludvig Peter (1896). Inscriptions de l'Orkhon déchiffrées. Helsingfors, Impr. de la Société de littérature finnoise. p. 140.

- Xu Elina-Qian, Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan, University of Helsinki, 2005. p. 179-180

- Maħmūd al-Kašğari. "Dīwān Luğāt al-Turk". Edited & translated by Robert Dankoff in collaboration with James Kelly. In Sources of Oriental Languages and Literature. Part I. (1982). p. 82-83