Hawaiian Pidgin

Hawaiian Pidgin English (alternately Hawaiian Creole English or HCE, known locally as Pidgin) is an English-based creole language spoken in Hawaiʻi (L1: 600,000; L2: 400,000).[3] Although English and Hawaiian are the co-official languages of the state of Hawaiʻi,[4] Hawaiian Pidgin is spoken by many Hawaiʻi residents in everyday conversation and is often used in advertising targeted toward locals in Hawaiʻi. In the Hawaiian language, it is called ʻōlelo paʻi ʻai - "pounding-taro language".[5]

| Hawaiian Creole English | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Hawai‘i, United States |

Native speakers | 600,000 (2015)[1] |

English Creole

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | hwc |

| Glottolog | hawa1247[2] |

| Linguasphere | 52-ABB-dc |

Despite its name, Hawaiian Pidgin is not a pidgin, but rather a full-fledged, nativized, and demographically stable creole language.[6] It did, however, evolve from various real pidgins spoken as common languages between ethnic groups in Hawaiʻi.

Although it is not completely mutually intelligible with Standard American English, Hawaiian Pidgin retains the highest degree of mutual intelligibility with it when compared with other English-based creoles, such as Jamaican Patois, in part due to its relatively recent emergence and the tendency for many of its speakers to mix Pidgin with Standard English.

History

Hawaiian Pidgin originated on sugarcane plantations as a form of communication used between Hawaiian speaking Native Hawaiian residents, English speaking residents, and foreign immigrants.[7] It supplanted, and was influenced by, the existing pidgin that Native Hawaiians already used on plantations and elsewhere in Hawaiʻi. Because such sugarcane plantations often hired workers from many different countries, a common language was needed in order for the plantation workers to communicate effectively with each other and their supervisors.[8] Hawaiian Pidgin has been influenced by many different languages, including Portuguese, Hawaiian, American English, and Cantonese. As people of other language backgrounds were brought in to work on the plantations, such as Japanese, Okinawans, Filipinos, and Koreans, Hawaiian Pidgin acquired words from these languages. The article Japanese loanwords in Hawaiʻi lists some of those words originally from Japanese. It has also been influenced to a lesser degree by Spanish spoken by Puerto Rican settlers in Hawaiʻi. Hawaiian Pidgin also takes loanwords from the Hawaiian Language.[9] Hawaiian Pidgin was created mainly as a means of communication or to facilitate cooperation between the immigrants and the Americans to get business done.[10] Even today, Hawaiian Pidgin retains some influences from these languages. For example, the word "stay" in Hawaiian Pidgin has a form and use similar to the Hawaiian verb "noho", Portuguese verb "ficar" or Spanish "estar", which mean "to be" but are used only when referring to a temporary state or location.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Hawaiian Pidgin started to be used outside the plantation between ethnic groups. In the 1980s two educational programs started that were led in Hawaiian Pidgin to help students learn Standard English.[11] Public school children learned Hawaiian Pidgin from their classmates and parents. Living in a community mixed with various cultures led to the daily usage of Hawaiian Pidgin, also causing the language to expand. It was easier for school children of different ethnic backgrounds to speak Hawaiian Pidgin than to learn another language.[12] Children growing up with this language expanded Hawaiian Pidgin as their first language, or mother tongue.[13] For this reason, linguists generally consider Hawaiian Pidgin to be a creole language.[14] A five-year survey that the U.S. Census Bureau conducted in Hawaiʻi and released in November 2015 revealed that many people spoke Pidgin as an additional language. Because of this, in 2015, the U.S. Census Bureau added Pidgin to its list of official languages in the state of Hawaiʻi.[15]

Phonology

Hawaiian Pidgin has distinct pronunciation differences from standard American English (SAE). Long vowels are not pronounced in Hawaiian Pidgin if the speaker is using Hawaiian loanwords.[9] Some key differences include the following:

- Th-stopping: /θ/ and /ð/ are pronounced as [t̼] or [d̼] respectively—that is, changed from a fricative to a plosive (stop). For instance, think /θiŋk/ becomes [t̼iŋk], and that /ðæt/ becomes [d̼æt]. An example is “Broke da mout” (tasted good).

- L-vocalization: Word-final l [l~ɫ] is often pronounced [o] or [ol]. For instance, mental /mɛntəl/ is often pronounced [mɛntoː]; people is pronounced [pipo].

- Hawaiian Pidgin is non-rhotic. That is, r after a vowel is often omitted, similar to many dialects, such as Eastern New England, Australian English, and British English variants. For instance, car is often pronounced cah, and letter is pronounced letta. Intrusive r is also used. The number of Hawaiian Pidgin speakers with rhotic English has also been increasing.

- Hawaiian Pidgin has falling intonation in questions. In yes/no questions, falling intonation is striking and appears to be a lasting imprint of Hawaiian (this pattern is not found in yes/no question intonation in American English). This particular falling intonation pattern is shared with some other Oceanic languages, including Fijian and Samoan (Murphy, K. 2013).

| Vowels[16] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | |

| i y ɪ |

u ʊ |

High | |

| e ɛ |

ʌ ɝ | o ɔ |

Mid |

| æ a |

ɑ | Low | |

Others include: /ü/, /ʉu̠/, /aɔ̠/ /aɪ/ /öɪ̠/ /ɑu/ /ɔi/ and /ju/.[16]

| Pulmonic consonants[17][18][19] | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place → | Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Laryngeal | ||||||||||||

| Manner ↓ | Bilabial | Labiodental | Linguolabial | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

| Stop | p | b | t̼ | d̼ | k | ɡ | ʔ | |||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||||||||

| Sibilant fricative | s | z | t̠ʃ | d̠ʒ | ||||||||||||

| Non-sibilant fricative | f | v | h | |||||||||||||

| Approximant | w | ɹ | ||||||||||||||

| Lateral approximant | l | |||||||||||||||

Grammatical Features

Hawaiian Pidgin has distinct grammatical forms not found in SAE, although some of them are shared with other dialectal forms of English or may derive from other linguistic influences.

Forms used for SAE "to be":

- Generally, forms of English "to be" (i.e. the copula) are omitted when referring to inherent qualities of an object or person, forming in essence a stative verb form. Additionally, inverted sentence order may be used for emphasis. (Many East Asian languages use stative verbs instead of the copula-adjective construction of English and other Western languages.)

- Da behbeh cute. (or) Cute, da behbeh.

- The baby is cute.

Note that these constructions also mimic the grammar of the Hawaiian language. In Hawaiian, "nani ka pēpē" is literally "beautiful the baby" retaining that specific syntactic form, and is perfectly correct Hawaiian grammar with equivalent meaning in English, "The baby is beautiful."

- When the verb "to be" refers to a temporary state or location, the word stay is used (see above). This may be influenced by other Pacific creoles, which use the word stap, from stop, to denote a temporary state or location. In fact, stop was used in Hawaiian Pidgin earlier in its history, and may have been dropped in favor of stay due to influence from Portuguese estar or ficar (ficar is literally translated to English as 'to stay', but often used in place of "to be" e.g. "ele fica feliz" he is happy).

- Da book stay on top da table.

- The book is on the table.

- Da watah stay cold.

- The water is cold.

For tense-marking of verb, auxiliary verbs are employed:

- To express past tense, Hawaiian Pidgin uses wen (went) in front of the verb.

- Jesus wen cry. ("Da Jesus Book", John 11:35)

- Jesus cried.

- To express future tense, Hawaiian Pidgin uses goin (going), derived from the going-to future common in informal varieties of American English.

- God goin do plenny good kine stuff fo him. ("Da Jesus Book", Mark 11:9)

- God is going to do a lot of good things for him.

- To express past tense negative, Hawaiian Pidgin uses neva (never). Neva can also mean "never" as in Standard English usage; context sometimes, but not always, makes the meaning clear.

- He neva like dat.

- He didn't want that. (or) He never wanted that. (or) He didn't like that.

- Use of fo (for) in place of the infinitive particle "to". Cf. dialectal form "Going for carry me home."

- I tryin fo tink. (or) I try fo tink.

- I'm trying to think.

Sociolinguistics

The language is highly stigmatized in formal settings, for which American English or the Hawaiian language are preferred. Therefore, its usage is typically reserved for everyday casual conversations.[20] Studies have proven that children in kindergarten preferred Hawaiian Pidgin, but once they were in grade one and more socially conditioned they preferred Standard English.[11] Hawaiian Pidgin is often criticized in business, educational, family, social, and community situations as it might be construed as rude, crude, or broken English among some Standard English speakers.[21] However, many tourists find Hawaiian Pidgin appealing - and local travel companies favor those who speak Hawaiian Pidgin and hire them as speakers or customer service agents.[22]

Most linguists categorize Hawaiian Pidgin as a creole, as a creole refers to the linguistic form “spoken by the native-born children of pidgin-speaking parents."[23] However, many locals view Hawaiian Pidgin as a dialect.[24] Other linguists argue that this “standard” form of the language is also a dialect. Based on this definition, a language is primarily the “standard” form of the language, but also an umbrella term used to encapsulate the “inferior” dialects of that language.[25]

The Pidgin Coup, a group of Hawaiian Pidgin advocates, claims that Hawaiian Pidgin should be classified as a language. The group believes that the only reason it is not considered a language is due to the hegemony of English. "Due to the hegemony of English, a lack of equal status between these two languages can only mean a scenario in which the non-dominant language is relatively marginalized. Marginalization occurs when people hold the commonplace view that HCE and English differ in being appropriate for different purposes and different situations. It is this concept of ‘appropriateness’ which is a form of prescriptivism; a newer, more subtle form."[26] These Hawaiian Pidgin advocates believe that by claiming there are only certain, less public contexts in which Hawaiian Pidgin is only appropriate, rather than explicitly stating that Hawaiian Pidgin is lesser than Standard English, masks the issue of refusing to recognize Hawaiian Pidgin as a legitimate language. In contrast, other researchers have found that many believe that, since Hawaiian Pidgin does not have a standardized writing form, it cannot be classified as a language.[27]

Literature and performing arts

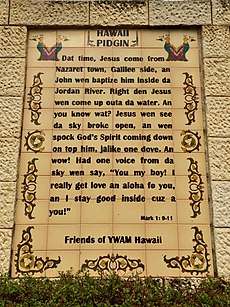

In recent years, writers from Hawaiʻi such as Lois-Ann Yamanaka, Joe Balaz, and Lee Tonouchi have written poems, short stories, and other works in Hawaiian Pidgin. A Hawaiian Pidgin translation of the New Testament (called Da Jesus Book) has also been created, as has an adaptation of William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, or What You Will, titled in Hawaiian Pidgin "twelf nite o' WATEVA!"[28]

Several theater companies in Hawaiʻi produce plays written and performed in Hawaiian Pidgin. The most notable of these companies is Kumu Kahua Theater.

The 1987 film North Shore contains several characters, particularly the surfing gang Da Hui, that speak Hawaiian Pidgin. This leads to humorous misunderstandings between the haole protagonist Rick Kane and several Hawaiian locals, including Rick’s best friend Turtle, who speaks Hawaiian Pidgin.

Hawaiian Pidgin has occasionally been featured on Hawaii Five-0 as the protagonists frequently interact with locals. A recurring character, Kamekona Tupuola (portrayed by Taylor Wiley), speaks Hawaiian Pidgin. The show frequently displays Hawaiian culture and is filmed at Hawaiʻi locations.

Milton Murayama's novel All I asking for is my body uses Hawaiʻi Pidgin in the title of the novel. R. Zamora Linmark employs it extensively in his semi-autobiographical novel Rolling the R's; two of the major characters speak predominately in Pidgin and some chapters are narrated in it. The novel also includes examples of Taglish.

Two books, Pidgin to Da Max humorously portray pidgin through prose and illustrations.

As of March 2008, Hawaiian Pidgin has started to become more popular in local television advertisements as well as other media.[9] When Hawaiian Pidgin is used in advertisements, it is often changed to better fit the targeted audience of the kama‘aina.[9]

See also

- Da kine

- Maritime Polynesian Pidgin, a Hawaiian-, Tahitian- and Maori-based pidgin that predated pidgin English in the Pacific.

Citations

- Hawaiian Creole English at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Hawaii Creole English". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- "Hawai'i Pidgin". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-06-25.

- "Hawaii State Constitution". Archived from the original on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "paʻi ʻai". Archived from the original on September 19, 2012. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- "Hawai'i Pidgin". Archived from the original on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Collins, Kathy (January–February 2008). "Da Muddah Tongue". www.mauinokaoimag.com – Maui nō ka ʻoi Magazine. Wailuku, HI, USA. OCLC 226379163. Archived from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- "Hawai'i Creole English". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Hiramoto, Mie (2011). "Consuming the consumers: Semiotics of Hawai'i Creole in advertisements". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 26 (2): 247–275. doi:10.1075/jpcl.26.2.02hir. ISSN 0920-9034.

- "Eye of Hawaii – Pidgin, The Unofficial Language of Hawaii". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Ohama, Mary Lynn Fiore; Gotay, Carolyn C.; Pagano, Ian S.; Boles, Larry; Craven, Dorothy D. (2000). "Evaluations of Hawaii Creole English and Standard English". Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 19 (3): 357–377. doi:10.1177/0261927x00019003005. ISSN 0261-927X.

- SIEGEL, JEFF (2000). "Substrate influence in Hawai'i Creole English". Language in Society. 29 (2): 197–236. doi:10.1017/s0047404500002025. ISSN 0047-4045.

- Department of Second Language Studies (2010). "Talking Story about Pidgin : What is Pidgin?". www.sls.hawaii.edu. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- Hargrove, Sakoda & Siegel 2017.

- Laddaran, Kerry Chan (2015-11-12). "Pidgin English is now an official language of Hawaii". CNN. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- Grama, James M., (2015). Variation and chang in Hawai'i Creole Vowels. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations Publishing (3717176)

- Murphy, Kelley Erin. (2013). Melodies of Hawai'i: The Relationship Between Hawai'i Creole English and 'Olelo Hawai'i Prosody Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations Publishing (NR96756)

- Odo, Carol. (1971). Variation in Hawaiian English: Underlying R. Retrieved from Eric.ed.gov

- Drager, Katie (2012). Pidgin and Hawai'i English: An Overview Retrieved from E. Journals Publishing

- Drager, Katie (2012-01-01). "Pidgin and Hawai'i English: An overview". International Journal of Language, Translation and Intercultural Communication. 1: 61–73. doi:10.12681/ijltic.10. ISSN 2241-7214.

- Marlow, Mikaela L.; Giles, Howard (2010). "'We won't get ahead speaking like that!' Expressing and managing language criticism in Hawai'i". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 31 (3): 237–251. doi:10.1080/01434630903582714. ISSN 0143-4632.

- "Hawaiian pidgin – Hawaiʻi's third language". Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Sato, Charlene J. (1985), "Linguistic Inequality in Hawaii: The Post-Creole Dilemma", Language of Inequality, DE GRUYTER, doi:10.1515/9783110857320.255, ISBN 9783110857320

- Fishman, Joshua A. (1977). ""Standard" versus "Dialect" in Bilingual Education: An Old Problem in a New Context". The Modern Language Journal. 61 (7): 315–325. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1977.tb05146.x. ISSN 0026-7902.

- "Internasjonal engelsk - Languages, Dialects, Pidgins and Creoles - NDLA". ndla.no. Retrieved 2019-01-06.

- Hargrove, Ermile; Sakoda, Kent (1999). "The Hegemony of English". Journal of Hawai'i Literature and Arts. 75: 48–68.

- Romaine, Suzanne (1999), "Changing Attitudes to Hawai'i Creole English", Creole Genesis, Attitudes and Discourse, Creole Language Library, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 20, p. 287, doi:10.1075/cll.20.20rom, ISBN 9789027252425

- F. Kathleen Foley (May 31, 1995). "THEATER REVIEW : 'Twelf Nite' a New Twist on Shakespeare". LA Times. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

References

- Da Jesus Book (2000). Orlando: Wycliffe Bible Translators. ISBN 0-938978-21-7.

- Murphy, Kelly (2013). Melodies of Hawai‘i: The relationship between Hawai‘i Creole English and ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi prosody. University of Calgary PhD dissertation.

- Sakoda, Kent & Jeff Siegel (2003). Pidgin Grammar: An Introduction to the Creole Language of Hawaiʻi. Honolulu: Bess Press. ISBN 1-57306-169-7.

- Simonson, Douglas et al. (1981). Pidgin to da Max. Honolulu: Bess Press. ISBN 0-935848-41-X.

- Tonouchi, Lee (2001). Da Word. Honolulu: Bamboo Ridge Press. ISBN 0-910043-61-2.

- "Pidgin: The Voice of Hawai'i." (2009) Documentary film. Directed by Marlene Booth, produced by Kanalu Young and Marlene Booth. New Day Films.

- Suein Hwang "Long Dismissed, Hawaii Pidgin Finds A Place in Classroom" (Cover story) Wall Street Journal – Eastern Edition, August 2005, retrieved on November 18, 2014.

- Digital History, Digital History, http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtid=2&psid=3159 2014, retrieved on November 18, 2014.

- Eye of Hawaii, Pidgin, The Unofficial Language, http://www.eyeofhawaii.com/Pidgin/pidgin.htm retrieved on November 18, 2014.

- Hargrove, Ermile; Sakoda, Kent; Siegel, Jeff. "Hawai'i Creole English". Language Varieties Web Site. University of Hawai'i. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- Jeff Siegel, Emergence of Pidgin and Creole Languages (Oxford University Press, 2008), 3.

- Hawaiian Pidgin, Hawaii Travel Guide http://www.to-hawaii.com/hawaiian-pidgin.php retrieved on November 18, 2014.

Further reading

- Murphy, Kelly (2013). Melodies of Hawai‘i: The relationship between Hawai‘i Creole English and ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi prosody. University of Calgary PhD dissertation.

- Sally Stewart (2001). "Hawaiian English". Lonely Planet USA Phrasebook. Lonely Planet Publications. pp. 262–266. ISBN 978-1-86450-182-7.

- Speidel, Gisela E. (1981). "Language and reading: bridging the language difference for children who speak Hawaiian English". Educational Perspectives. 20: 23–30.

- Speidel, G. E., Tharp, R. G., and Kobayashi, L. (1985). "Is there a comprehension problem for children who speak nonstandard English? A study of children with Hawaiian English backgrounds". Applied Psycholinguistics. 6 (1): 83–96. doi:10.1017/S0142716400006020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- e-Hawaii.com Searchable Pidgin English Dictionary

- The Charlene Sato Center for Pidgin, Creole and Dialect Studies, a center devoted to pidgin, creole, and dialect studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Hawaiʻi. Also home of the Pidgin Coup, a group of academics and community members interested in Hawaiʻi Pidgin related research and education

- Position Paper on Pidgin by the "Pidgin Coup"

- Da Hawaiʻi Pidgin Bible (see Da Jesus Book above)

- "Liddo Bitta Tita" Hawaiian Pidgin column written by Tita, alter-ego of Kathy Collins. Maui No Ka 'Oi Magazine Vol.12 No.1 (January 2008).

- "Liddo Bitta Tita" audio file

- Collection of Hawaii Creole English recordings available through Kaipuleohone