Vernacular architecture

Vernacular architecture is architecture characterised by the use of local materials and knowledge, usually without the supervision of professional architects. Vernacular architecture represents the majority of buildings and settlements created in pre-industrial societies and includes a very wide range of buildings, building traditions, and methods of construction.[1] Vernacular buildings are typically simple and practical, whether residential houses or built for other purposes.[2]

Although it encompassed 95% of the world's built environment in 1969,[3] vernacular architecture tends to be overlooked in traditional histories of design. It is not one specific style, so it cannot be distilled into a series of easy-to-digest patterns, materials, or elements.[4] Because of the usage of traditional building methods and local builders, vernacular buildings are considered part of a regional culture.

Vernacular architecture can be contrasted against elite or polite architecture, which is characterized by stylistic elements of design intentionally incorporated for aesthetic purposes which go beyond a building's functional requirements. This article also covers the term traditional architecture, which exists somewhere between the two extremes yet still is based upon authentic themes.[5]

Etymology

The term vernacular means "domestic, native, indigenous"; from verna, meaning "native slave" or "home-born slave". The word probably derives from an older Etruscan word.[6][7][8]

The term is borrowed from linguistics, where vernacular refers to language use particular to a time, place or group.[9][10][11]

Definitions

Vernacular architecture is described as a built environment that is based upon local needs; defined by the availability of particular materials indigenous to its particular region; and reflects local traditions and cultural practices. Traditionally, the study of vernacular architecture did not examine formally schooled architects, but instead that of the design skills and tradition of local builders, who were rarely given any attribution for the work. More recently, vernacular architecture has been examined by designers and the building industry in an effort to be more energy conscious with contemporary design and construction—part of a broader interest in sustainable design.

The terms vernacular, folk, traditional, common, ordinary, and popular architecture are sometimes used interchangeably. However, Allen Noble wrote a lengthy discussion of these terms in Traditional Buildings: A Global Survey of Structural Forms and Cultural Functions where he presents scholarly opinions that folk building or folk architecture is built by "persons not professionally trained in building arts"; where vernacular architecture is still of the common people but may be built by trained professionals such as through an apprenticeship, but still using local, traditional designs and materials. Traditional architecture is architecture passed down from person to person, generation to generation, particularly orally, but at any level of society, not just by common people. Noble discourages use of the term primitive architecture as having a negative connotation.[12] The term popular architecture is used more in eastern Europe and is synonymous with folk or vernacular architecture.[13]

Although vernacular architecture might be designed by people who do have some training in design, Ronald Brunskill has nonetheless defined vernacular architecture as:

...a building designed by an amateur without any training in design; the individual will have been guided by a series of conventions built up in his locality, paying little attention to what may be fashionable. The function of the building would be the dominant factor, aesthetic considerations, though present to some small degree, being quite minimal. Local materials would be used as a matter of course, other materials being chosen and imported quite exceptionally.[14]

Vernacular architecture is not to be confused with so-called "traditional" architecture, though there are links between the two. Traditional architecture also includes buildings which bear elements of polite design: temples and palaces, for example, which normally would not be included under the rubric of "vernacular." In architectural terms, 'the vernacular' can be contrasted with 'the polite', which is characterised by stylistic elements of design intentionally incorporated by a professional architect for aesthetic purposes which go beyond a building's functional requirements.[15] Between the extremes of the wholly vernacular and the completely polite, examples occur which have some vernacular and some polite content,[16] often making the differences between the vernacular and the polite a matter of degree.

The Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World defines vernacular architecture as:

...comprising the dwellings and all other buildings of the people. Related to their environmental contexts and available resources they are customarily owner- or community-built, utilizing traditional technologies. All forms of vernacular architecture are built to meet specific needs, accommodating the values, economies and ways of life of the cultures that produce them.[17]

Vernacular architecture is a broad, grassroots concept which encompasses fields of architectural study including aboriginal, indigenous, ancestral, rural, and ethnic architecture[18] and is contrasted with the more intellectual architecture called polite, formal, or academic architecture just as folk art is contrasted with fine art.

William,[15] after Brunskill, regards the 'Vernacular Zone' as being a range of buildings between two thresholds: the Vernacular and the Polite.[19] These were below the Polite Threshold, but also had to be above the Vernacular Threshold. Buildings cruder than this did not survive, and so were not recorded. This was due to both their unimportance and the lack of attention paid to them, also to the insubstantial nature of their poor materials. A survey in the 1940s by Sir Cyril Fox and Lord Raglan examined 450 'old' cottages in Monmouthshire expected to date them to the medieval period. However careful study dated them to the late eighteenth century or later: 'cottages'[lower-roman 1] earlier than this had simply not survived.[15][20]

Vernacular and the architect

Architecture designed by professional architects is usually not considered to be vernacular. Indeed, it can be argued that the very process of consciously designing a building makes it not vernacular. Paul Oliver, in his book Dwellings, states: "...it is contended that 'popular architecture' designed by professional architects or commercial builders for popular use, does not come within the compass of the vernacular".[21]:15 Oliver also offers the following simple definition of vernacular architecture: "the architecture of the people, and by the people, but not for the people."[21]:14

Frank Lloyd Wright described vernacular architecture as "Folk building growing in response to actual needs, fitted into environment by people who knew no better than to fit them with native feeling".[21]:9 suggesting that it is a primitive form of design, lacking intelligent thought, but he also stated that it was "for us better worth study than all the highly self-conscious academic attempts at the beautiful throughout Europe".

Since at least the Arts and Crafts Movement, many modern architects have studied vernacular buildings and claimed to draw inspiration from them, including aspects of the vernacular in their designs. In 1946, the Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy was appointed to design the town of New Gourna near Luxor. Having studied traditional Nubian settlements and technologies, he incorporated the traditional mud brick vaults of the Nubian settlements in his designs. The experiment failed, due to a variety of social and economic reasons, but is the first recorded attempt by an architect to address the social and environmental requirements of building users by adopting the methods and forms of the vernacular.[21]:11

In 1964, the exhibition Architecture Without Architects was put on at the Museum of Modern Art, New York by Bernard Rudofsky. Accompanied by a book of the same title, including black-and-white photography of vernacular buildings around the world, the exhibition was extremely popular. It was Rudofsky who first made use of the term vernacular in an architectural context, and brought the concept into the eye of the public and of mainstream architecture: "For want of a generic label we shall call it vernacular, anonymous, spontaneous, indigenous, rural, as the case may be."[22] However, the range of studies about vernacular architecture since the book's publication suggests that Rudofsky's characterization was limiting and problematic; indeed, quite often vernacular architecture is not anonymous and designed in very intentional ways that are learned through generations of practice and based upon the availability of particular materials and profoundly affected by climate (and, thus, not "spontaneous.")

Since the emergence of the term in the 1970s, vernacular considerations have played an increasing part in architectural designs, although individual architects had widely varying opinions of the merits of the vernacular.

Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa is considered the pioneer of regional modernism in South Asia. Along with him, modern proponents of the use of the vernacular in architectural design include Charles Correa, a well known Indian architect; Muzharul Islam and Bashirul Haq, internationally known Bangladeshi architects; Balkrishna Doshi, another Indian, who established the Vastu-Shilpa Foundation in Ahmedabad to research the vernacular architecture of the region; and Sheila Sri Prakash who has used rural Indian architecture as an inspiration for innovations in environmental and socio-economically sustainable design and planning. The Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck was also a proponent of vernacular architecture.[21]:13 Architects whose work exemplifies the modern take on vernacular architecture would be Samuel Mockbee, Christopher Alexander and Paolo Soleri.

Oliver claims that:

As yet there is no clearly defined and specialized discipline for the study of dwellings or the larger compass of vernacular architecture. If such a discipline were to emerge it would probably be one that combines some of the elements of both architecture and anthropology with aspects of history and geography.[21]

Architects have developed a renewed interest in vernacular architecture as a model for sustainable design.[23]

Influences on the vernacular

Vernacular architecture is influenced by a great range of different aspects of human behaviour and environment, leading to differing building forms for almost every different context; even neighbouring villages may have subtly different approaches to the construction and use of their dwellings, even if they at first appear the same. Despite these variations, every building is subject to the same laws of physics, and hence will demonstrate significant similarities in structural forms.

Climate

One of the most significant influences on vernacular architecture is the macro climate of the area in which the building is constructed. Buildings in cold climates invariably have high thermal mass or significant amounts of insulation. They are usually sealed in order to prevent heat loss, and openings such as windows tend to be small or non-existent. Buildings in warm climates, by contrast, tend to be constructed of lighter materials and to allow significant cross-ventilation through openings in the fabric of the building.

Buildings for a continental climate must be able to cope with significant variations in temperature, and may even be altered by their occupants according to the seasons. In hot arid and semi-arid regions, vernacular structures typically include a number of distinctive elements to provide for ventilation and temperature control. Across the middle-east, these elements included such design features as courtyard gardens with water features, screen walls, reflected light, mashrabiya (the distinctive oriel window with timber lattice-work) and bad girs (wind-catchers).[24]

Buildings take different forms depending on precipitation levels in the region – leading to dwellings on stilts in many regions with frequent flooding or rainy monsoon seasons. For example, the Queenslander is an elevated weatherboard house with a sloped, tin roof that evolved in the early 19th-century as a solution to the annual flooding caused by monsoonal rain in Australia's northern states.[25] Flat roofs are rare in areas with high levels of precipitation. Similarly, areas with high winds will lead to specialised buildings able to cope with them, and buildings tend to present minimal surface area to prevailing winds and are often situated low on the landscape to minimise potential storm damage.

Climatic influences on vernacular architecture are substantial and can be extremely complex. Mediterranean vernacular, and that of much of the Middle East, often includes a courtyard with a fountain or pond; air cooled by water mist and evaporation is drawn through the building by the natural ventilation set up by the building form. Similarly, Northern African vernacular often has very high thermal mass and small windows to keep the occupants cool, and in many cases also includes chimneys, not for fires but to draw air through the internal spaces. Such specializations are not designed, but learned by trial and error over generations of building construction, often existing long before the scientific theories which explain why they work. Vernacular architecture is also used for the purposes of local citizens.

Culture

The way of life of building occupants, and the way they use their shelters, is of great influence on building forms. The size of family units, who shares which spaces, how food is prepared and eaten, how people interact and many other cultural considerations will affect the layout and size of dwellings.

For example, the family units of several East African ethnic communities live in family compounds, surrounded by marked boundaries, in which separate single-roomed dwellings are built to house different members of the family. In polygamous communities there may be separate dwellings for different wives, and more again for sons who are too old to share space with the women of the family. Social interaction within the family is governed by, and privacy is provided by, the separation between the structures in which family members live. By contrast, in Western Europe, such separation is accomplished inside one dwelling, by dividing the building into separate rooms.

Culture also has a great influence on the appearance of vernacular buildings, as occupants often decorate buildings in accordance with local customs and beliefs.

Nomadic dwellings

There are many cultures around the world which include some aspect of nomadic life, and they have all developed vernacular solutions for the need for shelter. These all include appropriate responses to climate and customs of their inhabitants, including practicalities of simple construction such as huts, and if necessary, transport such as tents.

The Inuit people have a number of different forms of shelter appropriate to different seasons and geographical locations, including the igloo (for winter) and the tupiq (for summer). The Sami of Northern Europe, who live in climates similar to those experienced by the Inuit, have developed different shelters appropriate to their culture[21]:25 including the lavvu and goahti. The development of different solutions in similar circumstances because of cultural influences is typical of vernacular architecture.

Many nomadic people use materials common in the local environment to construct temporary dwellings, such as the Punan of Sarawak who use palm fronds, or the Ituri Pygmies who use saplings and mongongo leaves to construct domed huts. Other cultures reuse materials, transporting them with them as they move. Examples of this are the tribes of Mongolia, who carry their gers (yurts) with them, or the black desert tents of the Qashgai in Iran.[21]:29 Notable in each case is the significant impact of the availability of materials and the availability of pack animals or other forms of transport on the ultimate form of the shelters.

All the shelters are adapted to suit the local climate. The Mongolian gers (yurts), for example, are versatile enough to be cool in hot continental summers and warm in the sub-zero temperaturs of Mongolian winters, and include a close-able ventilation hole at the centre and a chimney for a stove. A ger is typically not often relocated, and is therefore sturdy and secure, including wooden front door and several layers of coverings. A traditional Berber tent, by contrast, might be relocated daily, and is much lighter and quicker to erect and dismantle – and because of the climate it is used in, does not need to provide the same degree of protection from the elements.

Tuareg tent during Colonial exhibition in 1907.

Tuareg tent during Colonial exhibition in 1907.

Arab Beduin tent from North Africa. Similar tents are also used by Arabs in the Middle East as well as by Persian and Tibetan nomads.

Arab Beduin tent from North Africa. Similar tents are also used by Arabs in the Middle East as well as by Persian and Tibetan nomads. A Berber tent near Zagora, Morocco

A Berber tent near Zagora, Morocco- In transhumance (the seasonal movement of people with their livestock to pasture) the herders stay in huts or tents.

Interior of a mudhif; a reed dwelling used by Iraqi people of the marshlands

Interior of a mudhif; a reed dwelling used by Iraqi people of the marshlands

Permanent dwellings

The type of structure and materials used for a dwelling vary depending on how permanent it is. Frequently moved nomadic structures will be lightweight and simple, more permanent ones will be less so. When people settle somewhere permanently, the architecture of their dwellings will change to reflect that.

Materials used will become heavier, more solid and more durable. They may also become more complicated and more expensive, as the capital and labour required to construct them is a one-time cost. Permanent dwellings often offer a greater degree of protection and shelter from the elements. In some cases however, where dwellings are subjected to severe weather conditions such as frequent flooding or high winds, buildings may be deliberately "designed" to fail and be replaced, rather than requiring the uneconomical or even impossible structures needed to withstand them. The collapse of a relatively flimsy, lightweight structure is also less likely to cause serious injury than a heavy structure.

Over time, dwellings' architecture may come to reflect a very specific geographical locale.

Environment, construction elements and materials

The local environment and the construction materials it can provide, govern many aspects of vernacular architecture. Areas rich in trees will develop a wooden vernacular, while areas without much wood may use mud or stone. In early California redwood water towers supporting redwood tanks and enclosed by redwood siding (tankhouses) were part of a self-contained wind-powered domestic water system. In the Far East it is common to use bamboo, as it is both plentiful and versatile. Vernacular, almost by definition, is sustainable, and will not exhaust the local resources. If it is not sustainable, it is not suitable for its local context, and cannot be vernacular.

Construction elements and materials frequently found in vernacular buildings include:

- Adobe – a type of mud brick, often covered with white-wash, commonly used in Spain and Spanish colonies

- Bad girs – a type of chimney used to provide natural ventilation, commonly found in Iran, Iraq and other parts of the Middle-East

- Cob – a type of plaster made from subsoil with the addition of fibrous material to give added strength

- Mashrabiya (also known as shanashol in Iraq) – a type of oriel window with timber lattice-work, designed to allow ventilation, commonly found in Iraq and Egypt in upper-class homes

- Mud bricks – loam or sand mixed with water and vegetable matter such as straw

- Rammed earth often used in foundations

- Thatch – dry vegetation used as roofing material

- Wychert – a blend of white earth and clay

Literature

Following the eclipse by International Modernism of turn-of-the 20th century vernacular-inspired British and American Arts and Crafts buildings and European National Romanticism, an early work in the renewed defense of vernacular was Bernard Rudofsky's 1964 book Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture, based on his MoMA exhibition. The book was a reminder of the legitimacy and "hard-won knowledge" inherent in vernacular buildings, from Polish salt-caves to gigantic Syrian water wheels to Moroccan desert fortresses, and was considered iconoclastic at the time. Rudofsky was, however, very much a Romantic who viewed native populations in a historical bubble of contentment. Rudofsky's book was also based largely on photographs and not on on-site study.

A more nuanced work is the Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World edited in 1997 by Paul Oliver of the Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development. Oliver argues that vernacular architecture, given the insights it gives into issues of environmental adaptation, will be necessary in the future to "ensure sustainability in both cultural and economic terms beyond the short term." Christopher Alexander, in his book A Pattern Language, attempted to identify adaptive features of traditional architecture that apply across cultures. Howard Davis's book The Culture of Building details the culture that enabled several vernacular traditions.

Some extend the term "vernacular" to include any architecture outside the academic mainstream. The term "commercial vernacular", popularized in the late 1960s by the publication of Robert Venturi's "Learning from Las Vegas", refers to 20th-century American suburban tract and commercial architecture. There is also the concept of an "industrial vernacular" with its emphasis on the aesthetics of shops, garages and factories. Some have linked vernacular with "off-the-shelf" aesthetics. In any respect, those who study these types of vernaculars hold that the low-end characteristics of this aesthetic define a useful and fundamental approach to architectural design.

Among those who study vernacular architecture are those who are interested in the question of everyday life and those lean toward questions of sociology. In this, many were influenced by The Practice of Everyday Life (1984) by Michel de Certeau.

Humanitarian response

An appreciation of vernacular architecture is increasingly seen as vital in the immediate response to disasters and the following construction of transitional shelter if it is needed. The work Transitional Settlement: Displaced Populations, produced by Shelter Centre covers the use of vernacular in humanitarian response and argues its importance.

The value of housing displaced people in shelters which are in some way familiar is seen to provide reassurance and comfort following often very traumatic times. As the needs change from saving lives to providing medium to long term shelter the construction of locally appropriate and accepted housing can be very important.[26]

Legal aspects

As many jurisdictions introduce tougher building codes and zoning regulations, "folk architects" sometimes find themselves in conflict with the local authorities.

A case that made news in Russia was that of an Arkhangelsk entrepreneur Nikolay P. Sutyagin, who built what was reportedly the world's tallest single-family wooden house for himself and his family, only to see it condemned as a fire hazard. The 13-storey, 44 m (144 ft) tall[27][28] structure, known locally as "Sutyagin's skyscraper" (Небоскрёб Сутягина), was found to be in violation of Arkhangelsk building codes, and in 2008 the courts ordered the building to be demolished by February 1, 2009.[27][29] On December 26, 2008, the tower was pulled down,[30][31] and the remainder was dismantled manually[32] over the course of the next several months.[33]

Gallery

Africa

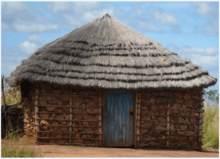

Rondavel in Cameroon.

Rondavel in Cameroon..jpg) Traditional houses in Tanzania

Traditional houses in Tanzania Maasai house in Tanzania

Maasai house in Tanzania

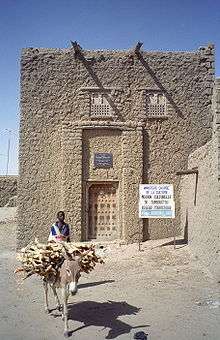

A house in Timbuktu.

A house in Timbuktu..jpg) Funco house in Cape Verde

Funco house in Cape Verde

Anatolia

Timber framed house in Safranbolu, as found in northern Anatolia and European Ottoman territories.

Timber framed house in Safranbolu, as found in northern Anatolia and European Ottoman territories. Late Ottoman wooden Yali, a type found on the Bosphorus shore and on the Princess Islands.

Late Ottoman wooden Yali, a type found on the Bosphorus shore and on the Princess Islands. A typical alpine chalet as found in the Pontic Mountains and parts of the Caucasus.

A typical alpine chalet as found in the Pontic Mountains and parts of the Caucasus.

Central Asia

Ayil - Herding House in the Altai Mountains

Ayil - Herding House in the Altai Mountains

A house made of bark - Aalachic. Алтай

A house made of bark - Aalachic. Алтай Shepherd's house in the mountains. Kosh-Agach

Shepherd's house in the mountains. Kosh-Agach

Animal Farm in the Altai Mountains

Animal Farm in the Altai Mountains Stone Yurt in Mongolia

Stone Yurt in Mongolia Telengits yurt in Altai

Telengits yurt in Altai

Middle East

.jpg) Traditional Yemeni house in Sana'a.

Traditional Yemeni house in Sana'a..jpg) Traditional Yemeni house in Sana'a.

Traditional Yemeni house in Sana'a.- Traditional architecture of the Hejaz, Al-Balad, Jeddah.

Replica of a vernacular house in Dubai, including a windcatcher.

Replica of a vernacular house in Dubai, including a windcatcher. Traditional brick house of Iran and Central Asia, Tabriz.

Traditional brick house of Iran and Central Asia, Tabriz. The mashrabiya (a type of oriel window) is a characteristic feature of upper-class homes across the region as in this example from Jerusalem

The mashrabiya (a type of oriel window) is a characteristic feature of upper-class homes across the region as in this example from Jerusalem

South Asia

.jpg)

Bhimakali temple, built in Kath-Kuni style of architecture, Indian vernacular architecture.

Bhimakali temple, built in Kath-Kuni style of architecture, Indian vernacular architecture.

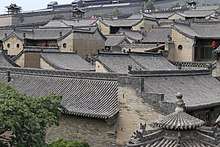

Far East Asia

Southeast Asia and Austronesian

- A traditional house, Nias Island, Sumatra, Indonesia.

Rumah Lancang or Rumah Lontiok style, a traditional Malay house from Riau, Sumatra, Indonesia.

Rumah Lancang or Rumah Lontiok style, a traditional Malay house from Riau, Sumatra, Indonesia.- Pagaruyung Palace is an opulent example of Rumah Gadang, vernacular house of the Minangkabau people, Sumatra, Indonesia

_en_duiventil_TMnr_10017427.jpg) House of the chief of a village in Kabanjahe shows the vernacular architecture of North Sumatran Karo people.

House of the chief of a village in Kabanjahe shows the vernacular architecture of North Sumatran Karo people. A nipa hut, the traditional house of the Philippines

A nipa hut, the traditional house of the Philippines Bahay na bato houses in the cultural and historical areas of the Philippines

Bahay na bato houses in the cultural and historical areas of the Philippines.jpg) "Tube house", popular among the major ethnic group in Vietnam, the Kinh people.

"Tube house", popular among the major ethnic group in Vietnam, the Kinh people.

Australia and New Zealand

Moscow Villa Hut, Victorian Alps, Australia

Moscow Villa Hut, Victorian Alps, Australia "Queenslanders" in Brisbane, Australia

"Queenslanders" in Brisbane, Australia

Europe

A traditional village house near Kstovo, Russia.

A traditional village house near Kstovo, Russia.

Payerhütte in the Ortler Alps, Italy

Payerhütte in the Ortler Alps, Italy The Blackhouse Museum, Arnol, Isle of Lewis. Scotland

The Blackhouse Museum, Arnol, Isle of Lewis. Scotland

.jpg)

North America

Replica log cabin at Valley Forge, USA

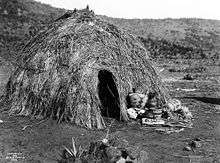

Replica log cabin at Valley Forge, USA Apache Wickiup

Apache Wickiup The Maison Bequette-Ribault, a French style building in Ste. Geneviève, Missouri.

The Maison Bequette-Ribault, a French style building in Ste. Geneviève, Missouri. Maison Bolduc, in Ste. Geneviève, Missouri is a grander building in the same style as the Maison Bequette-Ribault.

Maison Bolduc, in Ste. Geneviève, Missouri is a grander building in the same style as the Maison Bequette-Ribault. The Lasource-Durand house in Ste. Geneviève, Missouri.

The Lasource-Durand house in Ste. Geneviève, Missouri. A house on Gabouri Creek in Ste. Geneviève, Missouri.

A house on Gabouri Creek in Ste. Geneviève, Missouri.

Slave cabin, Arundel Plantation, Georgetown County, South Carolina

Slave cabin, Arundel Plantation, Georgetown County, South Carolina An abandoned and decaying example of Southern American Rural Vernacular architecture commonly seen in the 1800s and 1900s, surviving well into the 21st Century

An abandoned and decaying example of Southern American Rural Vernacular architecture commonly seen in the 1800s and 1900s, surviving well into the 21st Century

South America

A Mar del Plata style chalet, with its traditional facade of locally extracted orthoquartzite in Mar del Plata, Argentina

A Mar del Plata style chalet, with its traditional facade of locally extracted orthoquartzite in Mar del Plata, Argentina Oca, a communal house typical of the indigenous people of Brazil.

Oca, a communal house typical of the indigenous people of Brazil..jpeg)

A maloca, typical of the indigenous peoples of the Amazon Rainforest.

A maloca, typical of the indigenous peoples of the Amazon Rainforest.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vernacular architecture by country. |

Types and examples by region

Canadian

- Candian Railway style, Railway stations built in Canada in the 19th and early 20th Centuries were often simple wood structures that lacked decorative features. Some of these stations survive today but not as active railway stations.

Iraq

- Desert castles – (in Arabic, known as q'sar) fortified palaces or castles built during the Umayyad period, the ruins of which are now scattered across the semi-arid regions of north-eastern Jordan, Syria, Palestine and Iraq. These often served as hunting lodges for noble families.[35]

- Mudhif – a traditional building constructed entirely of reeds and common to the Marsh Arabs of southern Iraq. Many were destroyed by Saddam Hussein, but since 2003, Arab communities have been returning to their traditional homes and way of life.[36]

Germany

Norway

Scotland

- Bastle house – a multi-storey, fortified farmhouses with sophisticated security measures designed to provide defense against the frequent raiding parties along the Scottish border.[37]

- Blackhouse – a traditional dry-stone walls building, roofed with thatch of turf, a flagstones floor and central hearth, designed to accommodate livestock and people, separated by a partition.[38]

- Crofters cottage – a simple construction of stone walls filled with earth for insulation, a thatched or turf roof and stone slabs were set into the middle of the room for a peat fire which provided some form of central heating. An unusual croft house Brotchie's Steading, Dunnet was built with whale bone couples.[39]

- Cruck house – a medieval structure designed to cope with shortages of long-span timber. The frame of the structure uses "siles" or "couples" (a type of fork) for the end walls. The walls do not support the roof, which is instead carried on the cruck frame. This type of building is common throughout England, Scotland and Wales, although only a few intact examples have survived.[40]

- Shieling – a type of temporary hut (or a collection of huts) constructed of stone, sod and turf used as a dwelling during the Summer months when highlanders took their livestock to higher ground in search of new pasture.[41]

- Tower house or peel tower – a medieval building, typically of stone, constructed by the aristocratic classes as a defensible residence.[42]

- Turf house – e.g. East Ayrshire, Medieval turf house

Spain

- Adobe house - mudbrick buildings found in Spain and Spanish colonies

United States

- Creole architecture in the United States - a type of house or cottage common along the Gulf Coast and associated rivers, especially in southern Louisiana and Mississippi.[43]

- Vernacular Architecture of Rural and Small-Town Missouri, by Howard Wight Marshall[44]

- Earl A. Young (born March 31, 1889 – May 24, 1975) was an American architect, realtor and insurance agent. Over a span of 52 years, he designed and built 31 structures in Charlevoix, Michigan but was never a registered architect.[45][46] He worked mostly in stone, using limestone, fieldstone,[47] and boulders he found throughout Northern Michigan. The homes are commonly referred to as gnome homes, mushroom houses, or Hobbit houses.[45][46] His door, window, roof and fireplace designs were very distinct because of his use of curved lines. Young's goal was to show that a small stone house could be as impressive as a castle. Young also helped make Charlevoix the busy, summer resort town that it is today.[46][48]

Ukraine

Different regions in Ukraine have their own examples of vernacular architecture. For example, in the Carpathian Mountains and the surrounding foothills, wood and clay are the primary traditional building materials. Ukrainian architecture is preserved at The Museum of Folk Architecture and Way of Life of Central Naddnipryanshchyna located in Pereiaslav, Ukraine.

See also

Notes

- i.e. the homes of married labourers, rather than servants

References

- Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 750. ISBN 978-0415862875.

- Fewins, Clive. "What is Vernacular Style?". Homebuilding & Renovating. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- Amos Rapoport, House Form and Culture (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969), 2.

- J. Philip Gruen, “Vernacular Architecture,” in Encyclopedia of Local History, 3d edition, ed. Amy H. Wilson (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017): 697-98.

- Holm, 2006

- "Vernacular". online etymology dictionary. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- "Vernacular(noun)". yourdictionary.com. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- "Fiddling with words, again!". Tribune India. June 8, 2002. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- Dictionary.com definition

- Cambridge advanced learner's dictionary definition

- Merriam–Webster definition

- Noble, Allen George. Traditional buildings: a global survey of structural forms and cultural functions. London: I. B. Tauris, 2007. 1-17. Print.ISBN 9781845113056.

- The meanings in this paragraph are supported by the Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) © Oxford University Press 2009. Vernacular, a. and n., 6.; Folk 2. a.; Tradition, n., 4. a.; Traditional, a. (n.), 1. a.; Popular, a.(n.), 2. a.

- Brunskill (1971), pp. 27–28.

- William (2010), p. 241.

- Brunskill (1971), p. 28.

- Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World, volume 1, page not cited

- http://www.vernaculararchitecture.com/%5B%5D, a site which is part of http://www.ethnoarchitecture.org/ Archived 2013-05-07 at the Wayback Machine accessed 5/2/2013

- Brunskill (1971), pp. 25–29.

- Fox & Raglan (1954), p. 210.

- Oliver, Paul (2003). Dwellings. London: Phaidon Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-7148-4202-8.

- Rudofsky, Architecture Without Architects, page 58

- Forster, W., Heal, A. and Paradise, C., "The Vernacular as a Model for Sustainable Design" Chapter 14 in: W. Weber, S. Yannas, Lessons from Vernacular Architecture, Routledge, 2013

- Vernacular architecture at archINFORM

- Osborne, Lindy. "Sublime design: the Queenslander". Architecture & Design. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- "NGOs criticise tsunami shelters" BBC News – 22 December 2006

- Sutyagin House, Arkhangelsk, Russia: Standing tall. WorldArchitectureNews.com, Wednesday 07 Mar 2007. (Includes photo)

- According to other sources, 12 stories, 38 m (125 ft)

- Ponomaryova, Hope (26 June 2008). Гангстер-хаус: Самый высокий деревянный дом в России объявлен вне закона [Gangster house: Russia's tallest wooden house is now outlawed]. Rossiiskaya Gazeta (in Russian). Moscow, Russia. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- В Архангельске провалилась первая попытка снести самое высокое деревянное здание в мире [In Arkhangelsk failed first attempt to demolish the tallest wooden building in the world]. NEWSru.com Realty (Недвижимость) (in Russian). Moscow, Russia. 26 December 2008. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- mihai055 (December 26, 2008). Сутягин, снос дома [Sutyagin, demolition of houses] (Flash video) (in Russian). YouTube. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- В Архангельске разрушено самое высокое деревянное здание в мире [In Arkhangelsk destroyed the tallest wooden building in the world]. NEWSru.com Realty (Недвижимость) (in Russian). Moscow, Russia. 6 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- От самого высокого деревянного строения в мире осталась груда мусора [From the highest wooden structure in the world was left a pile of garbage] (flash video and text). Channel One Russia (in Russian). Moscow, Russia: Web-службой Первого канала. 6 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Masson, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich; Unesco (2003-01-01). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast : from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 9789231038761.

- Khouri, R.G., The Desert Castles: A Brief Guide to the Antiquities, Al Kutba, 1988. pp 4-5

- Broadbent, G., "The Ecology of the Mudhif," in: Geoffrey Broadbent and C. A. Brebbia, Eco-architecture II: Harmonisation Between Architecture and Nature, WIT Press, 2008, pp 21-23

- Brunskill, R. W., Houses and Cottages of Britain: Origins and Development of Traditional Buildings, Victor Gollancz & Peter Crawley, 1997, pp 28-29

- Holden, 2004

- Holden, 2003, pages 85-86

- Dixon, P., "The Medieval Peasant Building in Scotland: The Beginning and End of Crucks", Ruralia IV 2003, pp 187–200, Online

- Cheape, H., "Shielings in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland: Prehistory to the Present," Folk Life, Journal of Ethnological Studies, vol. 35, no. 1, 1996, pp 7-24, DOI: 10.1179/043087796798254498

- Mackechnie, A., "For Friendship and Conversation': Martial Scotland's Domestic Castles," Architectural Heritage, XXVI, 2015, p. 14 and p, 21

- Gamble, Robert Historic Architecture in Alabama: A Guide to Styles and Types, 1810-1930, page 180. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8173-1134-3.

- "vernacular architecture of missouri". Missourifolkloresociety.truman.edu. Retrieved 2013-09-02.

- Huyser-Honig, Joan (November 14, 1993). "Do Gnomes Live Here?". The Ann Arbor News. Archived from the original on February 19, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- Miles, David L (writer); Hull, Dale (narrator) (2009). The Life and Works of Earl Young, Charlevoix's Master Builder in Stone (DVD). Charlevoix Historical Society. OCLC 505817344.

- Eckert, Kathryn Bishop (1993). Buildings in Michigan. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 418. ISBN 0-19-506149-7.

- Kelly, Anne (January 1, 2010). "Earl Young and Don Campbell, Pals Who Shaped Charlevoix: The story of Earl Young, creator of Charlevoix's Hobbit Houses, and his lifelong friend Don Campbell, who traveled the world and ultimately shaped Charlevoix together". My North.com. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

Sources and further reading

- Bourgeois, Jean-Louis (1983). Spectacular vernacular: a new appreciation of traditional desert architecture. Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith Books. ISBN 0-87905-144-2. Large format.

- Brunskill, R.W. (2006) [1985]. Traditional Buildings of Britain: An Introduction to Vernacular Architecture. Cassell's. ISBN 0-304-36676-5.

- Brunskill, R.W. (2000) [1971]. Illustrated Handbook of Vernacular Architecture (4th ed.). London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-19503-2.

- Clifton-Taylor, Alec (1987) [1972]. The Pattern of English Building. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-13988-4. Clifton-Taylor pioneered the study of the English vernacular.

- Fox, Sir Cyril; Raglan, Lord (1954). Renaissance Houses. Monmouthshire Houses. III. Cardiff.

- Glassie, Henry. "Architects, Vernacular Traditions, and Society" Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, Vol 1, 1990, 9-21

- Holden, Timothy G; Baker, Louise M (2004). The Blackhouses of Arnol. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland. ISBN 1-904966-03-9.

- Holden, Timothy G (2003). "Brotchie's Steading (Dunnet parish), iron age and medieval settlement; post-medieval farm". Discovery and Excavation in Scotland (4): 85–86.

- Holm, Ivar (2006). 2006 [Ideas and Beliefs in Architecture and Industrial design: How attitudes, orientations, and underlying assumptions shape the built environment]. Oslo School of Architecture and Design. ISBN 82-547-0174-1.

- Mark Jarzombek, Architecture of First Societies: A Global Perspective, (New York: Wiley & Sons, August 2013)

- Oliver, Paul (2003). Dwellings. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-4202-8.

- Oliver, Paul, ed. (1997). Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-58269-8.

- Perez Gil, Javier (2016). ¿Que es la arquitectura vernacula? Historia y concepto de un patrimonio cultural especifico. Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid. ISBN 978-84-8448-862-0.

- Pruscha, Carl, ed. (2005) [2004]. [Himalayan Vernacular]. Köln: Verlag Der Buchhandlung Walther König. ISBN 3-85160-038-X. Carl Pruscha, Austrian architect and United Nations-UNESCO advisor to the government of Nepal, lived and worked in the Himalayas 1964–74. He continued his activities as head of the design studio "Habitat, Environment and Conservation" at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.

- Rudofsky, Bernard (1987) [1964]. Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-1004-4.

- Rudofsky, Bernard (1969). Streets for People: A Primer for Americans. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04231-0.

- Upton, Dell and John Michael Vlach, eds. Common Places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1986. ISBN 0-8203-0749-1.

- Wharton, David. "Roadside Architecture." Southern Spaces, February 1, 2005, http://southernspaces.org/2005/roadside-architecture.%5B%5D

- William, Eurwyn (2010). The Welsh Cottage. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. ISBN 978-1-871184-426.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vernacular architecture. |

- Center for Vernacular Architecture-Bangalore-India

- Vernacular Architecture Forum

- Vernacular Architecture Examples at GreatBuildings

- Vernacular Architecture and Landscape Architecture Research Guide – Environmental Design Library, University of California, Berkeley

- Himalayan Vernacular Architecture - Technische Universität Berlin

- DATs Fachwerk interiors (Germany)

.svg.png)