Estonia

Estonia (Estonian: Eesti [ˈeːsʲti] (![]()

Republic of Estonia | |

|---|---|

Anthem:

| |

Location of Estonia (dark green) – in Europe (green & grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Tallinna 59°25′N 24°45′E |

| Official language | Estonian |

| Ethnic groups (2020[1]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Estonian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Kersti Kaljulaid | |

| Jüri Ratas | |

| Legislature | Riigikogu |

| Independence | |

| 12 April 1917 | |

| 24 February 1918 | |

| 2 February 1920 | |

| 1940–1991 | |

• Independence restored | 20 August 1991 |

• Joined the European Union | 1 May 2004 |

| Area | |

• Total | 45,227[2] km2 (17,462 sq mi) (129thd) |

• Water (%) | 4.45% |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | |

• 2011 census | 1,294,455[4] |

• Density | 28/km2 (72.5/sq mi) (149th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $49.644 billion[5] |

• Per capita | $37,605[5] (43rd) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $32.742 billion[5] |

• Per capita | $24,802[5] (35th) |

| Gini (2018) | medium |

| HDI (2018) | very high · 30th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| UTC+3 (EEST) | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +372 |

| ISO 3166 code | EE |

| Internet TLD | .eee |

| |

The territory of Estonia has been inhabited since at least 9,000 BC. Ancient Estonians became some of the last European pagans to adopt Christianity following the Livonian Crusade in the 13th century.[13] After centuries of successive rule by Germans, Danes, Swedes, Poles and Russians, a distinct Estonian national identity began to emerge in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This culminated in independence from Russia in 1920 after a brief War of Independence at the end of World War I. Initially democratic prior to the Great Depression, Estonia experienced authoritarian rule from 1934 during the Era of Silence. During World War II (1939–1945), Estonia was repeatedly contested and occupied by the Soviet Union and Germany, ultimately being incorporated into the former. After the loss of its de facto independence, Estonia's de jure state continuity was preserved by diplomatic representatives and the government-in-exile. In 1987 the peaceful Singing Revolution began against Soviet rule, resulting in the restoration of de facto independence on 20 August 1991.

The sovereign state of Estonia is a democratic unitary parliamentary republic divided into fifteen counties. Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, and Tartu are largest cities and urban areas in the whole country. Other notable cities are Narva, Pärnu and Kohtla-Järve. With a population of 1.3 million Estonia is one of the least populous members of the European Union, the Eurozone, the OECD, the Schengen Area, NATO, and from 2020, the United Nations Security Council.[14]

Estonia is a developed country with an advanced, high-income economy that was among the fastest-growing in the EU since its entry in 2004[15] The country ranks very high in the Human Development Index,[7] and compares well in measures of economic freedom, civil liberties, education,[16] and press freedom.[17] Estonian citizens receive universal health care,[18] free education,[19] and the longest paid maternity leave in the OECD.[20] One of the world's most digitally-advanced societies,[21] in 2005 Estonia became the first state to hold elections over the Internet, and in 2014, the first state to provide e-residency.

Etymology

The name Estonia has been connected to Aesti, first mentioned by Roman historian Tacitus around 98 AD. Some historians believe he was directly referring to Balts (i.e. not Finnic-speaking Estonians), while others have proposed that the name applied to the whole Eastern Baltic region.[22] The Scandinavian sagas referring to Eistland were the earliest sources to use the name in its modern meaning.[23] The toponym Estland/Eistland has been linked to Old Scandinavian eist, austr meaning "the east".[24]

History

Prehistory and Viking Age

Human settlement in Estonia became possible 13,000 to 11,000 years ago, when the ice from the last glacial era melted. The oldest known settlement in Estonia is the Pulli settlement, which was on the banks of the river Pärnu, near the town of Sindi, in south-western Estonia. According to radiocarbon dating it was settled around 11,000 years ago.[25]

The earliest human habitation during the Mesolithic period is connected to the Kunda culture, named after the town of Kunda in northern Estonia. At that time the country was covered with forests, and people lived in semi-nomadic communities near bodies of water. Subsistence activities consisted of hunting, gathering and fishing.[26] Around 4900 BC ceramics appear of the neolithic period, known as Narva culture.[27] Starting from around 3200 BC the Corded Ware culture appeared; this included new activities like primitive agriculture and animal husbandry.[28]

The Bronze Age started around 1800 BC, and saw the establishment of the first hill fort settlements.[30] A transition from hunting-fishing-gathering subsistence to single-farm-based settlement started around 1000 BC, and was complete by the beginning of the Iron Age around 500 BC.[25][31] The large amount of bronze objects indicate the existence of active communication with Scandinavian and Germanic tribes.[32]

The middle Iron Age produced threats appearing from different directions. Several Scandinavian sagas referred to major confrontations with Estonians, notably when "Estonian Vikings" defeated and killed the Swedish king Ingvar.[33][34] Similar threats appeared in the east, where Russian principalities were expanding westward. In 1030 Yaroslav the Wise defeated Estonians and established a fort in modern-day Tartu; this foothold lasted until an Estonian tribe, the Sosols, destroyed it in 1061, followed by their raid on Pskov.[35][36][37][38] Around the 11th century, the Scandinavian Viking era around the Baltic Sea was succeeded by the Baltic Viking era, with seaborne raids by Curonians and by Estonians from the island of Saaremaa, known as Oeselians. In 1187 Estonians (Oeselians), Curonians or/and Karelians sacked Sigtuna, which was a major city of Sweden at the time.[39][40]

Estonia could be divided into two main cultural areas, the coastal areas of Northern and Western Estonia had close overseas contacts with Scandinavia and Finland, while inland Southern Estonia had more contacts with Balts and Pskov.[41] The landscape of Ancient Estonia featured numerous hillforts.[42] Prehistoric or medieval harbour sites have been found on the coast of Saaremaa.[42] Estonia also has a number of graves from the Viking Age, both individual and collective, with weapons and jewellery including types found commonly throughout Northern Europe and Scandinavia.[42][43]

In the early centuries AD, political and administrative subdivisions began to emerge in Estonia. Two larger subdivisions appeared: the parish (Estonian: kihelkond) and the county (Estonian: maakond), which consisted of multiple parishes. A parish was led by elders and centred around a hill fort; in some rare cases a parish had multiple forts. By the 13th century Estonia consisted of eight major counties: Harjumaa, Järvamaa, Läänemaa, Revala, Saaremaa, Sakala, Ugandi, and Virumaa; and six minor, single-parish counties: Alempois, Jogentagana, Mõhu, Nurmekund, Soopoolitse, and Vaiga. Counties were independent entities and engaged only in a loose co-operation against foreign threats.[44][45]

There is little known of early Estonian pagan religious practices. The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia mentions Tharapita as the superior god of the Oeselians. Spiritual practices were guided by shamans, with sacred groves, especially oak groves, serving as places of worship.[46][47]

Middle Ages

In 1199 Pope Innocent III declared a crusade to "defend the Christians of Livonia".[48] Fighting reached Estonia in 1206, when Danish king Valdemar II unsuccessfully invaded Saaremaa. The German Livonian Brothers of the Sword, who had previously subjugated Livonians, Latgalians, and Selonians, started campaigning against the Estonians in 1208, and over next few years both sides made numerous raids and counter-raids. A major leader of the Estonian resistance was Lembitu, an elder of Sakala County, but in 1217 the Estonians suffered a significant defeat in the Battle of St. Matthew's Day, where Lembitu was killed. In 1219, Valdemar II landed at Lindanise, defeated the Estonians in battle, and started conquering Northern Estonia.[49][50] The next year, Sweden invaded Western Estonia, but were repelled by the Oeselians. In 1223, a major revolt ejected the Germans and Danes from the whole of Estonia, except Reval, but the crusaders soon resumed their offensive, and in 1227, Saaremaa was the last county to surrender.[51][52]

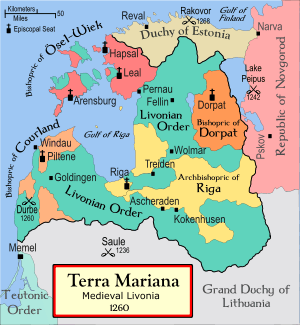

After the crusade, the territory of present-day Southern Estonia and Latvia was named Terra Mariana, but later it became known simply as Livonia.[53] Northern-Estonia became the Danish Duchy of Estonia, while the rest was divided between the Sword Brothers and prince-bishoprics of Dorpat and Ösel–Wiek. In 1236, after suffering a major defeat, the Sword Brothers merged into the Teutonic Order becoming the Livonian Order.[54] In the next decades there were several uprisings against foreign rulers on Saaremaa. In 1343, a major rebellion started, known as the St. George's Night Uprising, encompassing the whole area of Northern-Estonia and Saaremaa. The Teutonic Order finished suppressing the rebellion in 1345, and the next year the Danish king sold his possessions in Estonia to the Order.[55][56] The unsuccessful rebellion led to a consolidation of power for the Baltic German minority.[57] For the subsequent centuries they remained the ruling elite in both cities and the countryside.[58]

During the crusade, Reval (Tallinn) was founded, as the capital of Danish Estonia, on the site of Lindanise. In 1248 Reval received full town rights and adopted the Lübeck law.[59] The Hanseatic League controlled trade on the Baltic Sea, and overall the four largest towns in Estonia became members: Reval, Dorpat (Tartu), Pernau (Pärnu), and Fellin (Viljandi). Reval acted as a trade intermediary between Novgorod and Western Hanseatic cities, while Dorpat filled the same role with Pskov. Many guilds were formed during that period, but only a very few allowed the participation of native Estonians.[60] Protected by their stone walls and alliance with the Hansa, prosperous cities like Reval and Dorpat repeatedly defied other rulers of Livonia.[61] After the decline of the Teutonic Order after its defeat in the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, and the defeat of the Livonian Order in the Battle of Swienta on 1 September 1435, the Livonian Confederation Agreement was signed on 4 December 1435.[62]

The Reformation in Europe began in 1517, and soon spread to Livonia despite opposition by the Livonian Order.[63] Towns were the first to embrace Protestantism in the 1520s, and by the 1530s the majority of the gentry had adopted Lutheranism for themselves and their peasant serfs.[64][65] Church services were now conducted in vernacular language, which initially meant German, but in the 1530s the first religious services in Estonian also took place.[64][66]

During the 16th century, the expansionist monarchies of Muscowy, Sweden, and Poland–Lithuania consolidated power, posing a growing threat to decentralised Livonia weakened by disputes between cities, nobility, bishops, and the Order.[64][67]

Swedish Era

In 1558, Tsar Ivan the Terrible of Russia invaded Livonia, starting the Livonian War. The Livonian Order was decisively defeated in 1560, prompting Livonian factions to seek foreign protection. The majority of Livonia accepted Polish rule, while Reval and the nobles of Northern Estonia swore loyalty to the Swedish king, and the Bishop of Ösel-Wiek sold his lands to the Danish king. Russian forces gradually conquered the majority of Livonia, but in the late 1570s the Polish-Lithuanian and Swedish armies started their own offensives and the bloody war finally ended in 1583 with Russian defeat.[67][68] As result of the war, Northern Estonia became Swedish Duchy of Estonia, Southern Estonia became Polish Duchy of Livonia, and Saaremaa remained under Danish control.[69]

In 1600, the Polish-Swedish War broke out, causing further devastation. The protracted war ended in 1629 with Sweden gaining Livonia, including the regions of Southern Estonia and Northern Latvia.[70] Danish Saaremaa was transferred to Sweden in 1645.[71] The wars had halved the Estonian population from about 250–270,000 people in the mid 16th century to 115–120,000 in the 1630s.[72]

While serfdom was retained under Swedish rule, legal reforms took place which strengthened peasants' land usage and inheritance rights, resulting this period's reputation of the "Good Old Swedish Time" in people's historical memory.[73] Swedish king Gustaf II Adolf established gymnasiums in Reval and Dorpat; the latter was upgraded to Tartu University in 1632. Printing presses were also established in both towns. In the 1680s the beginnings of Estonian elementary education appeared, largely due to efforts of Bengt Gottfried Forselius, who also introduced orthographical reforms to written Estonian.[74] The population of Estonia grew rapidly for a 60–70-year period, until the Great Famine of 1695–97 in which some 70,000–75,000 people perished – about 20% of the population.[75]

Russian Era and National Awakening

In 1700, the Great Northern War started, and by 1710 the whole of Estonia was conquered by the Russian Empire.[76] The war again devastated the population of Estonia, with the 1712 population estimated at only 150,000–170,000.[77] Russian administration restored all the political and landholding rights of Baltic Germans.[78] The rights of Estonian peasants reached their lowest point, as serfdom completely dominated agricultural relations during the 18th century.[79] Serfdom was formally abolished in 1816–1819, but this initially had very little practical effect; major improvements in rights of the peasantry started with reforms in the mid-19th century.[80]

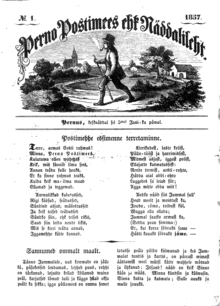

The Estonian national awakening began in the 1850s as the leading figures started promoting an Estonian national identity among the general populace. Its economic basis was formed by widespread farm buyouts by peasants, forming a class of Estonian landowners. In 1857 Johann Voldemar Jannsen started publishing the first Estonian language newspaper and began popularising the denomination of oneself as eestlane (Estonian).[81] Schoolmaster Carl Robert Jakobson and clergyman Jakob Hurt became leading figures in a national movement, encouraging Estonian peasants to take pride in themselves and in their ethnic identity.[82] The first nationwide movements formed, such as a campaign to establish the Estonian language Alexander School, the founding of the Society of Estonian Literati and the Estonian Students' Society, and the first national song festival, held in 1869 in Tartu.[83][84][85] Linguistic reforms helped to develop the Estonian language.[86] The national epic Kalevipoeg was published in 1862, and 1870 saw the first performances of Estonian theatre.[87][88] In 1878 a major split happened in the national movement. The moderate wing led by Hurt focused on development of culture and Estonian education, while the radical wing led by Jacobson started demanding increased political and economical rights.[84]

In the late 19th century the Russification period started, as the central government initiated various administrative and cultural measures to tie Baltic governorates more closely to the empire.[83] The Russian language was used throughout the education system and many Estonian social and cultural activities were suppressed.[88] Still, some administrative changes aimed at reducing power of Baltic German institutions did prove useful to Estonians.[83] In the late 1890s there was a new surge of nationalism with the rise of prominent figures like Jaan Tõnisson and Konstantin Päts. In the early 20th century Estonians started taking over control of local governments in towns from Germans.[89]

During the 1905 Revolution the first legal Estonian political parties were founded. An Estonian national congress was convened and demanded the unification of Estonian areas into a single autonomous territory and an end to Russification. During the unrest peasants and workers attacked manor houses. The Tsarist government responded with a brutal crackdown; some 500 people were executed and hundreds more were jailed or deported to Siberia.[90][91]

Independence

In 1917, after the February Revolution, the governorate of Estonia was expanded to include Estonian speaking areas of Livonia and was granted autonomy, enabling formation of the Estonian Provincial Assembly.[92] Bolsheviks seized power during the October Revolution, and disbanded the Provincial Assembly. However the Provincial Assembly established the Salvation Committee, and during the short interlude between Russian retreat and German arrival, the committee declared the independence of Estonia on 24 February 1918, and formed the Estonian Provisional Government. German occupation immediately followed, but after their defeat in World War I the Germans were forced to hand over power to the Provisional Government on 19 November.[93][94]

On 28 November 1918 Soviet Russia invaded, starting the Estonian War of Independence.[95] The Red Army came within 30 km from Tallinn, but in January 1919, the Estonian Army, led by Johan Laidoner, went on a counter-offensive, ejecting Bolshevik forces from Estonia within a few months. Renewed Soviet attacks failed, and in spring, the Estonian army, in co-operation with White Russian forces, advanced into Russia and Latvia.[96][97] In June 1919, Estonia defeated the German Landeswehr which had attempted to dominate Latvia, restoring power to the government of Kārlis Ulmanis there. After the collapse of the White Russian forces, the Red Army launched a major offensive against Narva in late 1919, but failed to achieve a breakthrough. On 2 February 1920, the Tartu Peace Treaty was signed between Estonia and Soviet Russia, with the latter pledging to permanently give up all sovereign claims to Estonia.[96][98]

In April 1919, the Estonian Constituent Assembly was elected. The Constituent Assembly passed a sweeping land reform expropriating large estates, and adopted a new highly liberal constitution establishing Estonia as a parliamentary democracy.[99][100] In 1924, the Soviet Union organised a communist coup attempt, which quickly failed.[101] Estonia's cultural autonomy law for ethnic minorities, adopted in 1925, is widely recognised as one of the most liberal in the world at that time.[102] The Great Depression put heavy pressure on Estonia's political system, and in 1933, the right-wing Vaps movement spearheaded a constitutional reform establishing a strong presidency.[103][104] On 12 March 1934 the acting head of state, Konstantin Päts, declared a state of emergency, falsely claiming that the Vaps movement had been planning a coup. Päts, together with general Johan Laidoner and Kaarel Eenpalu, established an authoritarian regime, where the parliament was dissolved and the newly established Patriotic League became the only legal political party.[105] To legitimise the regime, a new constitution was adopted and elections were held in 1938. Opposition candidates were allowed to participate, but only as independents, while opposition parties remained banned.[106] The Päts regime was relatively benign compared to other authoritarian regimes in interwar Europe, and there was no systematic terror against political opponents.[107]

Estonia joined the League of Nations in 1921.[108] Attempts to establish a larger alliance together with Finland, Poland, and Latvia failed, with only a mutual defence pact being signed with Latvia in 1923, and later was followed up with the Baltic Entente of 1934.[109][110] In the 1930s, Estonia also engaged in secret military co-operation with Finland.[111] Non-aggression pacts were signed with the Soviet Union in 1932, and with Germany in 1939.[108][112] In 1938, Estonia declared neutrality, but this proved futile in World War II.[113]

Second World War

On 23 August 1939 Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The pact's secret protocol divided Eastern Europe into spheres of influence, with Estonia belonging to the Soviet sphere.[114] On 24 September, the Soviet Union presented an ultimatum, demanding that Estonia sign a treaty of mutual assistance which would allow Soviet military bases into the country. The Estonian government felt that it had no choice but to comply, and the treaty was signed on 28 September.[115] In May 1940, Red Army forces in bases were set in combat readiness and, on 14 June, the Soviet Union instituted a full naval and air blockade on Estonia. On the same day, the airliner Kaleva was shot down by the Soviet Air Force. On 16 June, Soviets presented an ultimatum demanding completely free passage of the Red Army into Estonia and the establishment of a pro-Soviet government. Feeling that resistance was hopeless, the Estonian government complied and, on the next day, the whole country was occupied.[116][117] On 6 August 1940, Estonia was annexed by the Soviet Union as the Estonian SSR.[118]

The Soviets established a regime of oppression; most of the high-ranking civil and military officials, intelligentsia and industrialists were arrested, and usually executed soon afterwards. Soviet repressions culminated on 14 June 1941 with mass deportation of around 11,000 people to Siberia, among whom more than half perished in inhumane conditions.[119][120] When the German Operation Barbarossa started against the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, around 34,000 young Estonian men were forcibly drafted into the Red Army, fewer than 30% of whom survived the war. Soviet destruction battalions initiated a scorched earth policy. Political prisoners who could not be evacuated were executed by the NKVD.[121][122] Many Estonians went into the forest, starting an anti-Soviet guerrilla campaign. In July, German Wehrmacht reached south Estonia. Soviets evacuated Tallinn in late August with massive losses, and capture of the Estonian islands was completed by German forces in October.[123]

Initially many Estonians were hopeful that Germany would help to restore Estonia's independence, but this soon proved to be in vain. Only a puppet collaborationist administration was established, and occupied Estonia was merged into Reichskommissariat Ostland, with its economy being fully subjugated to German military needs.[124] About a thousand Estonian Jews who had not managed to leave were almost all quickly killed in 1941. Numerous forced labour camps were established where thousands of Estonians, foreign Jews, Romani, and Soviet prisoners of war perished.[125] German occupation authorities started recruiting men into small volunteer units but, as these efforts provided meagre results and military situation worsened, a forced conscription was instituted in 1943, eventually leading to formation of the Estonian Waffen-SS division.[126] Thousands of Estonians who did not want to fight in German military secretly escaped to Finland, where many volunteered to fight together with Finns against Soviets.[127]

The Red Army reached the Estonian borders again in early 1944, but its advance into Estonia was stopped in heavy fighting near Narva for six months by German forces, including numerous Estonian units.[128] In March, the Soviet Air Force carried out heavy bombing raids against Tallinn and other Estonian towns.[129] In July, the Soviets started a major offensive from the south, forcing the Germans to abandon mainland Estonia in September, with the Estonian islands being abandoned in November.[128] As German forces were retreating from Tallinn, the last pre-war prime minister Jüri Uluots appointed a government headed by Otto Tief in an unsuccessful attempt restore Estonia's independence.[130] Tens of thousands of people, including most of the Estonian Swedes, fled westwards to avoid the new Soviet occupation.[131]

Overall, Estonia lost about 25% of its population through deaths, deportations and evacuations in World War II.[132] Estonia also suffered some irrevocable territorial losses, as Soviet Union transferred border areas comprising about 5% of Estonian pre-war territory from the Estonian SSR to the Russian SFSR.[133]

Soviet Period

Thousands of Estonians opposing the second Soviet occupation joined a guerrilla movement known as Forest Brothers. The armed resistance was heaviest in the first few years after the war, but Soviet authorities gradually wore it down through attrition, and resistance effectively ceased to exist in the mid 1950s.[134] The Soviets initiated a policy of collectivisation, but as peasants remained opposed to it a campaign of terror was unleashed. In March 1949 about 20,000 Estonians were deported to Siberia. Collectivization was fully completed soon afterwards.[119][135]

The Soviet Union began Russification, with hundreds of thousands of Russians and people of other Soviet nationalities being induced to settle in Estonia, which eventually threatened to turn Estonians into a minority in their own land.[136] In 1945 Estonians formed 97% of the population, but by 1989 their share of the population had fallen to 62%.[137] Economically, heavy industry was strongly prioritised, but this did not improve the well-being of the local population, and caused massive environmental damage through pollution.[138] Living standards under the Soviet occupation kept falling further behind nearby independent Finland.[136] The country was heavily militarised, with closed military areas covering 2% of territory.[139] Islands and most of the coastal areas were turned into a restricted border zone which required a special permit for entry.[140]

The United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, and the majority of other Western countries considered the annexation of Estonia by the Soviet Union illegal.[141] Legal continuity of the Estonian state was preserved through the government-in-exile and the Estonian diplomatic representatives which Western governments continued to recognise.[142][143]

Restoration of Independence

The introduction of Perestroika in 1987 made political activity possible again, starting an independence restoration process known as the Singing Revolution.[144] The environmental Phosphorite War campaign became the first major protest movement against the central government.[145] In 1988 new political movements appeared, such as the Popular Front of Estonia which came to represent the moderate wing in the independence movement, and the more radical Estonian National Independence Party, which was the first non-communist party in the Soviet Union and demanded full restoration of independence.[146] Reformist Vaino Väljas became the first secretary of Estonian Communist Party, and under his leadership on 16 November 1988 Estonian Supreme Soviet issued Sovereignty Declaration asserting the primacy of Estonian laws over Union laws. Over the next two years almost all other Soviet Republics followed the Estonian lead issuing similar declarations.[147][148] On 23 August 1989 about 2 million Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians participated in a mass demonstration forming a Baltic Way human chain across the three republics.[149] In 1990 the Congress of Estonia was formed as representative body of Estonian citizens.[150] In March 1991 a referendum was held where 77.7% of voters supported independence, and during the coup attempt in Moscow Estonia declared restoration of independence on 20 August,[151] which is now the Day of Restoration of Independence, a national holiday.[152]

Soviet authorities recognised Estonian independence on 6 September, and on 17 September Estonia was admitted into the United Nations.[153] The last units of the Russian army left Estonia in 1994.[154]

In 1992 radical economic reforms were launched for switching over to a market economy, including privatisation and currency reform.[155] Estonian foreign policy since independence has been oriented toward the West, and in 2004 Estonia joined both the European Union and NATO.[156]

Territorial history timeline

|

Geography

Estonia lies on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea immediately across the Gulf of Finland, on the level northwestern part of the rising East European platform between 57.3° and 59.5° N and 21.5° and 28.1° E. Average elevation reaches only 50 metres (164 ft) and the country's highest point is the Suur Munamägi in the southeast at 318 metres (1,043 ft). There is 3,794 kilometres (2,357 mi) of coastline marked by numerous bays, straits, and inlets. The number of islands and islets is estimated at some 2,355 (including those in lakes). Two of them are large enough to constitute separate counties: Saaremaa and Hiiumaa.[157][158] A small, recent cluster of meteorite craters, the largest of which is called Kaali is found on Saaremaa, Estonia.

Estonia has over 1,400 lakes. Most are very small, with the largest, Lake Peipus, being 3,555 km2 (1,373 sq mi). There are many rivers in the country. The longest of them are Võhandu (162 km or 101 mi), Pärnu (144 km or 89 mi), and Põltsamaa (135 km or 84 mi).[157] Estonia has numerous fens and bogs. Forest land covers 50% of Estonia.[159] The most common tree species are pine, spruce and birch.[160]

Phytogeographically, Estonia is shared between the Central European and Eastern European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Estonia belongs to the ecoregion of Sarmatic mixed forests.

Climate

Estonia is situated in the northern part of the temperate climate zone and in the transition zone between maritime and continental climate. Estonia has four seasons of near-equal length. Average temperatures range from 16.3 °C (61.3 °F) on the islands to 18.1 °C (64.6 °F) inland in July, the warmest month, and from −3.5 °C (25.7 °F) on the islands to −7.6 °C (18.3 °F) inland in February, the coldest month. The average annual temperature in Estonia is 5.2 °C (41.4 °F).[161] The average precipitation in 1961–1990 ranged from 535 to 727 mm (21.1 to 28.6 in) per year.[162]

Snow cover, which is deepest in the south-eastern part of Estonia, usually lasts from mid-December to late March.

Biodiversity

Many species extinct in most of the European countries can be still found in Estonia. Mammals present in Estonia include the grey wolf, lynx, brown bear, red fox, badger, wild boar, moose, red deer, roe deer, beaver, otter, grey seal, and ringed seal. Critically endangered European mink has been successfully reintroduced to the island of Hiiumaa, and the rare Siberian flying squirrel is present in east Estonia.[163][164] Introduced species, such as the sika deer, raccoon dog and muskrat, can now be found throughout the country.[165] Over 300 bird species have been found in Estonia, including the white-tailed eagle, lesser spotted eagle, golden eagle, western capercaillie, black and white stork, numerous species of owls, waders, geese and many others.[166] The Barn swallow is the national bird of Estonia.[167]

Protected areas cover 18% of Estonian land and 26% of its sea territory. There are 6 national parks, 159 nature reserves, and many other protection areas.[168]

Politics

Estonia is a unitary parliamentary republic. The unicameral parliament Riigikogu serves as the legislative and the government as the executive.[169]

Estonian parliament Riigikogu is elected by citizens over 18 years of age for a four-year term by proportional representation, and has 101 members. Riigikogu's responsibilities include approval and preservation of the national government, passing legal acts, passing the state budget, and conducting parliamentary supervision. On proposal of the president Riigikogu appoints the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Estonia, the Auditor General, the Legal Chancellor, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Forces.[170][171]

The Government of Estonia is formed by the Prime Minister of Estonia at recommendation of the President, and approved by the Riigikogu. The government, headed by the Prime Minister, represent the political leadership of the country and carry out domestic and foreign policy. Ministers head ministries and represent its interests in the government. Sometimes ministers with no associated ministry are appointed, known as ministers without portfolio.[172] Estonia has been ruled by coalition governments because no party has been able to obtain an absolute majority in the parliament.[169]

The head of the state is the President who has primarily representative and ceremonial role. The president is elected by the Riigikogu, or by a special electoral college. The President proclaims the laws passed in the Riigikogu, and has right to refuse proclamation and return law in question for a new debate and decision. If Riigikogu passes the law unamended, then the President has right to propose to the Supreme Court to declare the law unconstitutional. The President also represents the country in international relations.[169][173]

The Constitution of Estonia also provides possibility for direct democracy through referendum, although since adoption of the constitution in 1992 the only referendum has been the referendum on European Union membership in 2003.[174]

Estonia has pursued the development of the e-government, with 99 percent of the public services being available on the web 24 hours a day.[175] In 2005 Estonia became the first country in the world to introduce nationwide binding Internet voting in local elections of 2005.[176] In 2019 parliamentary elections 44% of the total votes were cast over the internet.[177]

In the most recent parliamentary elections of 2019, five parties gained seats at Riigikogu. The head of the Centre Party, Jüri Ratas, formed the government together with Conservative People's Party and Isamaa, while Reform Party and Social Democratic Party became the opposition.[178]

Law

The Constitution of Estonia is the fundamental law, establishing the constitutional order based on five principles: human dignity, democracy, rule of law, social state, and the Estonian identity.[179] Estonia has a civil law legal system based on the Germanic legal model.[180] The court system has three-level structure. The first instance are county courts which handle all criminal and civil cases, and administrative courts which hear complaints about government and local officials, and other public disputes. The second instance are district courts which handle appeals about the first instance decisions.[181] The Supreme Court is the court of cassation, and also conducts constitutional review, it has 19 members.[182] The judiciary is independent, judges are appointed for life, and can be removed from office only then convicted by court for a criminal deed.[183] The Estonian justice system has been rated among the most efficient in the European Union by the EU Justice Scoreboard.[184]

Administrative divisions

Estonia is an unitary country with a single-tier local government system. Local affairs are managed autonomously by local governments. Since administrative reform in 2017, there are in total 79 local governments, including 15 towns and 64 rural municipalities. All municipalities have equal legal status and form part of a county, which is a state administrative unit.[185] Representative body of local authorities is municipal council, elected at general direct elections for a four-year term. The council appoints local government, headed by a mayor. For additional decentralization the local authorities may form municipal districts with limited authority, currently those have been formed in Tallinn and Hiiumaa.[186]

Separately from administrative units there are also settlement units: village, small borough, borough, and town. Generally villages have less than 300, small borough have between 300–1000, borough and town have over 1000 inhabitants.[186]

Foreign relations

Estonia was a member of the League of Nations from 22 September 1921, and became a member of the United Nations on 17 September 1991.[187][188] Since restoration of independence Estonia has pursued close relations with the Western countries, and has been member of NATO since 29 March 2004, as well as the European Union since 1 May 2004.[188] In 2007, Estonia joined the Schengen Area, and in 2011 the Eurozone.[188] The European Union Agency for large-scale IT systems is based in Tallinn, which started operations at the end of 2012.[189] Estonia held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the second half of 2017.[190]

Since the early 1990s, Estonia has been involved in active trilateral Baltic states co-operation with Latvia and Lithuania, and Nordic-Baltic co-operation with the Nordic countries. The Baltic Council is the joint forum of the interparliamentary Baltic Assembly and the intergovernmental Baltic Council of Ministers.[191] Estonia has built close relationship with the Nordic countries, especially Finland and Sweden, and is a member of Nordic-Baltic Eight (NB-8) uniting Nordic and Baltic countries.[188][192] Joint Nordic-Baltic projects include the education programme Nordplus[193] and mobility programmes for business and industry[194] and for public administration.[195] The Nordic Council of Ministers has an office in Tallinn with a subsidiaries in Tartu and Narva.[196][197] The Baltic states are members of Nordic Investment Bank, European Union's Nordic Battle Group, and in 2011 were invited to co-operate with NORDEFCO in selected activities.[198][199][200][201]

.jpg)

The beginning of the attempt to redefine Estonia as "Nordic" was seen in December 1999, when then Estonian foreign minister (and President of Estonia from 2006 until 2016) Toomas Hendrik Ilves delivered a speech entitled "Estonia as a Nordic Country" to the Swedish Institute for International Affairs,[202] with potential political calculation behind it being wish to distinguish Estonia from more slowly progressing southern neighbours, which could have postponed early participation in European Union enlargement for Estonia too.[203] Andres Kasekamp argued in 2005, that relevance of identity discussions in Baltic states decreased with their entrance into EU and NATO together, but predicted, that in the future, attractiveness of Nordic identity in Baltic states will grow and eventually, five Nordic states plus three Baltic states will become a single unit.[203]

Other Estonian international organisation memberships include OECD, OSCE, WTO, IMF, the Council of the Baltic Sea States,[188][204][205] and on 7 June 2019, was elected a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council for a term that begins on 1 January 2020.[14]

Relations with Russia remain generally cold, though there is some practical co-operation.[206]

Military

.jpg)

The Estonian Defence Forces consist of land forces, navy, and air force. The current national military service is compulsory for healthy men between ages of 18 and 28, with conscripts serving 8 or 11-month tours of duty, depending on their education and position provided by the Defence Forces.[207] The peacetime size of the Estonian Defence Forces is about 6,000 persons, with half of those being conscripts. The planned wartime size of the Defence Forces is 60,000 personnel, including 21,000 personnel in high readiness reserve.[208] Since 2015 the Estonian defence budget has been over 2% of GDP, fulfilling its NATO defence spending obligation.[209]

The Estonian Defence League is a voluntary national defence organisation under management of Ministry of Defence. It is organized based on military principles, has its own military equipment, and provides various different military training for its members, including in guerilla tactics. The Defence League has 16,000 members, with additional 10,000 volunteers in its affiliated organisations.[210][211]

Estonia co-operates with Latvia and Lithuania in several trilateral Baltic defence co-operation initiatives. As part of Baltic Air Surveillance Network (BALTNET) the three countries man a Baltic airspace control center, Baltic Battalion (BALTBAT) has participated in the NATO Response Force, and a joint military educational institution Baltic Defence College is located in Tartu.[212]

Estonia joined NATO in 2004. NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence was established in Tallinn in 2008.[213] In response to Russian military operations in Ukraine, since 2017 NATO Enhanced Forward Presence battalion battle group has been based in Tapa Army Base.[214] Also part of NATO Baltic Air Policing deployment has been based in Ämari Air Base since 2014.[215] In European Union Estonia participates in Nordic Battlegroup and Permanent Structured Cooperation.[216][217]

Since 1995 Estonia has participated in numerous international security and peacekeeping missions, including: Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Kosovo, and Mali.[218] The peak strength of Estonian deployment in Afghanistan was 289 soldiers in 2009.[219] 11 Estonian soldiers have been killed in missions of Afghanistan and Iraq.[220]

Economy

As a member of the European Union, Estonia is considered a high-income economy by the World Bank. The GDP (PPP) per capita of the country was $29,312 in 2016 according to the International Monetary Fund.[5] Because of its rapid growth, Estonia has often been described as a Baltic Tiger beside Lithuania and Latvia. Beginning 1 January 2011, Estonia adopted the euro and became the 17th eurozone member state.[221]

According to Eurostat, Estonia had the lowest ratio of government debt to GDP among EU countries at 6.7% at the end of 2010.[222] A balanced budget, almost non-existent public debt, flat-rate income tax, free trade regime, competitive commercial banking sector, innovative e-Services and even mobile-based services are all hallmarks of Estonia's market economy.

Estonia produces about 75% of its consumed electricity.[223] In 2011, about 85% of it was generated with locally mined oil shale.[224] Alternative energy sources such as wood, peat, and biomass make up approximately 9% of primary energy production. Renewable wind energy was about 6% of total consumption in 2009.[225] Estonia imports petroleum products from western Europe and Russia. Estonia imports 100% of its natural gas from Russia.[226] Oil shale energy, telecommunications, textiles, chemical products, banking, services, food and fishing, timber, shipbuilding, electronics, and transportation are key sectors of the economy.[227] The ice-free port of Muuga, near Tallinn, is a modern facility featuring good transshipment capability, a high-capacity grain elevator, chill/frozen storage, and new oil tanker off-loading capabilities. The railroad serves as a conduit between the West, Russia, and other points.

Because of the global economic recession that began in 2007, the GDP of Estonia decreased by 1.4% in the 2nd quarter of 2008, over 3% in the 3rd quarter of 2008, and over 9% in the 4th quarter of 2008. The Estonian government made a supplementary negative budget, which was passed by Riigikogu. The revenue of the budget was decreased for 2008 by EEK 6.1 billion and the expenditure by EEK 3.2 billion.[228] In 2010, the economic situation stabilised and started a growth based on strong exports. In the fourth quarter of 2010, Estonian industrial output increased by 23% compared to the year before. The country has been experiencing economic growth ever since.[229]

According to Eurostat data, Estonian PPS GDP per capita stood at 67% of the EU average in 2008.[230] In 2017, the average monthly gross salary in Estonia was €1221.[231]

However, there are vast disparities in GDP between different areas of Estonia; currently, over half of the country's GDP is created in Tallinn.[232] In 2008, the GDP per capita of Tallinn stood at 172% of the Estonian average,[233] which makes the per capita GDP of Tallinn as high as 115% of the European Union average, exceeding the average levels of other counties.

The unemployment rate in March 2016 was 6.4%, which is below the EU average,[231] while real GDP growth in 2011 was 8.0%,[234] five times the euro-zone average. In 2012, Estonia remained the only euro member with a budget surplus, and with a national debt of only 6%, it is one of the least indebted countries in Europe.[235]

Economic indicators

Estonia's economy continues to benefit from a transparent government and policies that sustain a high level of economic freedom, ranking 6th globally and 2nd in Europe.[236][237] The rule of law remains strongly buttressed and enforced by an independent and efficient judicial system. A simplified tax system with flat rates and low indirect taxation, openness to foreign investment, and a liberal trade regime have supported the resilient and well-functioning economy.[238] As of May 2018, the Ease of Doing Business Index by the World Bank Group places the country 16th in the world.[239] The strong focus on the IT sector has led to much faster, simpler and efficient public services where for example filing a tax return takes less than five minutes and 98% of banking transactions are conducted through the internet.[240][241] Estonia has the third lowest business bribery risk in the world, according to TRACE Matrix.[242]

| Rank/Country | Business Bribery Risk Score | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Sweden | 10 | ||||||||

| 3 Estonia | 17 | ||||||||

| 8 Singapore | 25 | ||||||||

| 10 Denmark | 27 | ||||||||

| 12 Canada | 28 | ||||||||

| 14 Switzerland | 29 | ||||||||

| 20 United States | 34 | ||||||||

| 31 Belgium | 40 | ||||||||

| 94 Russian Federation | 58 | ||||||||

|

Lower score = Less risk. Source: TRACE Matrix[242] | |||||||||

| Country | Rank | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong[lower-alpha 1] | 1 | 89.8 |

| Singapore | 2 | 88.6 |

| New Zealand | 3 | 83.7 |

| Switzerland | 4 | 81.5 |

| Australia | 5 | 81.0 |

| Estonia | 6 | 79.1 |

| Canada | 7 | 78.5 |

| United Arab Emirates | 8 | 76.9 |

| Ireland | 9 | 76.7 |

| Chile | 10 | 76.5 |

Historic development

In 1928, a stable currency, the kroon, was established. It is issued by the Bank of Estonia, the country's central bank. The word kroon (Estonian pronunciation: [ˈkroːn], "crown") is related to that of the other Nordic currencies (such as the Swedish krona and the Danish and Norwegian krone). The kroon succeeded the mark in 1928 and was used until 1940. After Estonia regained its independence, the kroon was reintroduced in 1992.

Since re-establishing independence, Estonia has styled itself as the gateway between East and West and aggressively pursued economic reform and integration with the West. Estonia's market reforms put it among the economic leaders in the former COMECON area. In 1994, based on the economic theories of Milton Friedman, Estonia became one of the first countries to adopt a flat tax, with a uniform rate of 26% regardless of personal income. This rate has since been reduced three times, to 24% in January 2005, 23% in January 2006, and finally to 21% by January 2008.[243] The Government of Estonia finalised the design of Estonian euro coins in late 2004, and adopted the euro as the country's currency on 1 January 2011, later than planned due to continued high inflation.[221][244] A Land Value Tax is levied which is used to fund local municipalities. It is a state level tax, however 100% of the revenue is used to fund Local Councils. The rate is set by the Local Council within the limits of 0.1–2.5%. It is one of the most important sources of funding for municipalities.[245] The Land Value Tax is levied on the value of the land only with improvements and buildings not considered. Very few exemptions are considered on the land value tax and even public institutions are subject to the tax.[245] The tax has contributed to a high rate (~90%)[245] of owner-occupied residences within Estonia, compared to a rate of 67.4% in the United States.[246]

In 1999, Estonia experienced its worst year economically since it regained independence in 1991, largely because of the impact of the 1998 Russian financial crisis. Estonia joined the WTO in November 1999. With assistance from the European Union, the World Bank and the Nordic Investment Bank, Estonia completed most of its preparations for European Union membership by the end of 2002 and now has one of the strongest economies of the new member states of the European Union. Estonia joined the OECD in 2010.[247]

Resources

Although Estonia is in general resource-poor, the land still offers a large variety of smaller resources. The country has large oil shale and limestone deposits, along with forests that cover 48% of the land.[251] In addition to oil shale and limestone, Estonia also has large reserves of phosphorite, pitchblende, and granite that currently are not mined, or not mined extensively.[252]

Significant quantities of rare-earth oxides are found in tailings accumulated from 50 years of uranium ore, shale and loparite mining at Sillamäe.[253] Because of the rising prices of rare earths, extraction of these oxides has become economically viable. The country currently exports around 3000 tonnes per annum, representing around 2% of world production.[254]

Since 2008, public debate has discussed whether Estonia should build a nuclear power plant to secure energy production after closure of old units in the Narva Power Plants, if they are not reconstructed by the year 2016.[255][256]

Industry and environment

Food, construction, and electronic industries are currently among the most important branches of Estonia's industry. In 2007, the construction industry employed more than 80,000 people, around 12% of the entire country's workforce.[257] Another important industrial sector is the machinery and chemical industry, which is mainly located in Ida-Viru County and around Tallinn.

The oil shale-based mining industry, which is also concentrated in East-Estonia, produces around 90% of the entire country's electricity. Although the amount of pollutants emitted to the air have been falling since the 1980s,[258] the air is still polluted with sulphur dioxide from the mining industry that the Soviet Union rapidly developed in the early 1950s. In some areas the coastal seawater is polluted, mainly around the Sillamäe industrial complex.[259]

Estonia is a dependent country in the terms of energy and energy production. In recent years many local and foreign companies have been investing in renewable energy sources. The importance of wind power has been increasing steadily in Estonia and currently the total amount of energy production from wind is nearly 60 MW while at the same time roughly 399 MW worth of projects are currently being developed and more than 2800 MW worth of projects are being proposed in the Lake Peipus area and the coastal areas of Hiiumaa.[260][261][262]

Currently, there are plans to renovate some older units of the Narva Power Plants, establish new power stations, and provide higher efficiency in oil shale-based energy production.[263] Estonia liberalised 35% of its electricity market in April 2010. The electricity market as whole will be liberalised by 2013. [264]

Together with Lithuania, Poland, and Latvia, the country considered participating in constructing the Visaginas nuclear power plant in Lithuania to replace the Ignalina.[265][266] However, due to the slow pace of the project and problems with the sector (like Fukushima disaster and bad example of Olkiluoto plant), Eesti Energia has shifted its main focus to shale oil production that is seen as much more profitable business.[267]

Estonia has a strong information technology sector, partly owing to the Tiigrihüpe project undertaken in the mid-1990s, and has been mentioned as the most "wired" and advanced country in Europe in the terms of e-Government of Estonia.[268] A new direction is to offer those services present in Estonia to the non-residents via e-residency program.

Skype was written by Estonia-based developers Ahti Heinla, Priit Kasesalu, and Jaan Tallinn, who had also originally developed Kazaa.[269] Other notable tech startups include GrabCAD, Fortumo and TransferWise. It is even claimed that Estonia has the most startups per person in world.[270]

The Estonian electricity network forms a part of the Nord Pool Spot network.[271]

Trade

Estonia has had a market economy since the end of the 1990s and one of the highest per capita income levels in Eastern Europe.[272] Proximity to the Scandinavian and Finnish markets, its location between the East and West, competitive cost structure and a highly skilled labour force have been the major Estonian comparative advantages in the beginning of the 2000s (decade). As the largest city, Tallinn has emerged as a financial centre and the Tallinn Stock Exchange joined recently with the OMX system. Several cryptocurrency trading platforms are officially recognised by the government, such as CoinMetro.[273] The current government has pursued tight fiscal policies, resulting in balanced budgets and low public debt.

In 2007, however, a large current account deficit and rising inflation put pressure on Estonia's currency, which was pegged to the Euro, highlighting the need for growth in export-generating industries. Estonia exports mainly machinery and equipment, wood and paper, textiles, food products, furniture, and metals and chemical products.[274] Estonia also exports 1.562 billion kilowatt hours of electricity annually.[274] At the same time Estonia imports machinery and equipment, chemical products, textiles, food products and transportation equipment.[274] Estonia imports 200 million kilowatt hours of electricity annually.[274]

Between 2007 and 2013, Estonia received 53.3 billion kroons (3.4 billion euros) from various European Union Structural Funds as direct supports, creating the largest foreign investments into Estonia.[275] Majority of the European Union financial aid will be invested into the following fields: energy economies, entrepreneurship, administrative capability, education, information society, environment protection, regional and local development, research and development activities, healthcare and welfare, transportation and labour market.[276] Main sources of foreign direct investments to Estonia are Sweden and Finland (As of 31 December 2016 48.3%).[277]

Demographics

Before World War II, ethnic Estonians constituted 88% of the population, with national minorities constituting the remaining 12%.[280] The largest minority groups in 1934 were Russians, Germans, Swedes, Latvians, Jews, Poles, Finns and Ingrians.

The share of Baltic Germans in Estonia had fallen from 5.3% (~46,700) in 1881 to 1.3% (16,346) by the year 1934,[280][281] which was mainly due to emigration to Germany in the light of general Russification in the end of the 19th century and the independence of Estonia in the 20th century.

Between 1945 and 1989, the share of ethnic Estonians in the population resident within the currently defined boundaries of Estonia dropped to 61%, caused primarily by the Soviet programme promoting mass immigration of urban industrial workers from Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, as well as by wartime emigration and Joseph Stalin's mass deportations and executions. By 1989, minorities constituted more than one-third of the population, as the number of non-Estonians had grown almost fivefold.

At the end of the 1980s, Estonians perceived their demographic change as a national catastrophe. This was a result of the migration policies essential to the Soviet Nationalisation Programme aiming to russify Estonia – administrative and military immigration of non-Estonians from the USSR coupled with the deportation of Estonians to the USSR. In the decade after the reconstitution of independence, large-scale emigration by ethnic Russians and the removal of the Russian military bases in 1994 caused the proportion of ethnic Estonians in Estonia to increase from 61% to 69% in 2006.

Modern Estonia is a fairly ethnically heterogeneous country, but this heterogeneity is not a feature of much of the country as the non-Estonian population is concentrated in two of Estonia's counties. Thirteen of Estonia's 15 counties are over 80% ethnic Estonian, the most homogeneous being Hiiumaa, where Estonians account for 98.4% of the population. In the counties of Harju (including the capital city, Tallinn) and Ida-Viru, however, ethnic Estonians make up 60% and 20% of the population, respectively. Russians make up 25.6% of the total population but account for 36% of the population in Harju county and 70% of the population in Ida-Viru county.

The Estonian Cultural Autonomy law that was passed in 1925 was unique in Europe at that time.[282] Cultural autonomies could be granted to minorities numbering more than 3,000 people with longstanding ties to the Republic of Estonia. Before the Soviet occupation, the Germans and Jewish minorities managed to elect a cultural council. The Law on Cultural Autonomy for National Minorities was reinstated in 1993. Historically, large parts of Estonia's northwestern coast and islands have been populated by indigenous ethnically Rannarootslased (Coastal Swedes).

In recent years the numbers of Coastal Swedes has risen again, numbering in 2008 almost 500 people, owing to the property reforms in the beginning of the 1990s. In 2004, the Ingrian Finnish minority in Estonia elected a cultural council and was granted cultural autonomy. The Estonian Swedish minority similarly received cultural autonomy in 2007.

Society

Estonian society has undergone considerable changes over the last twenty years, one of the most notable being the increasing level of stratification, and the distribution of family income. The Gini coefficient has been steadily higher than the European Union average (31 in 2009),[283] although it has clearly dropped. The registered unemployment rate in January 2012 was 7.7%.[284]

Modern Estonia is a multinational country in which 109 languages are spoken, according to a 2000 census. 67.3% of Estonian citizens speak Estonian as their native language, 29.7% Russian, and 3% speak other languages.[285] As of 2 July 2010, 84.1% of Estonian residents are Estonian citizens, 8.6% are citizens of other countries and 7.3% are "citizens with undetermined citizenship".[286] Since 1992 roughly 140,000 people have acquired Estonian citizenship by passing naturalisation exams.[287] Estonia has also accepted quota refugees under the migrant plan agreed upon by EU member states in 2015.[288]

The ethnic distribution in Estonia is very homogeneous, where in most counties over 90% of the people are ethnic Estonians. This is in contrast to large urban centres like Tallinn, where Estonians account for 60% of the population, and the remainder is composed mostly of Russian and other Slavic inhabitants, who arrived in Estonia during the Soviet period.

The 2008 United Nations Human Rights Council report called "extremely credible" the description of the citizenship policy of Estonia as "discriminatory".[289] According to surveys, only 5% of the Russian community have considered returning to Russia in the near future. Estonian Russians have developed their own identity – more than half of the respondents recognised that Estonian Russians differ noticeably from the Russians in Russia. When comparing the result with a survey from 2000, then Russians' attitude toward the future is much more positive.[290]

Estonia has been the first post-Soviet republic that has legalised civil unions of same-sex couples. The law was approved in October 2014 and came into effect 1 January 2016.[291]

53.3% of ethnically Estonian youth consider belonging in the Nordic identity group as important or very important for them. 52.2% have the same attitude towards the "Baltic" identity group, according to a research study from 2013:[292]

The image that Estonian youths have of their identity is rather similar to that of the Finns as far as the identities of being a citizen of one’s own country, a Fenno-Ugric person, or a Nordic person are concerned, while our identity as a citizen of Europe is common ground between us and Latvians – being stronger here than it is among the young people of Finland and Sweden.[292]

Urbanization

Tallinn is the capital and the largest city of Estonia, and lies on the northern coast of Estonia, along the Gulf of Finland. There are 33 cities and several town-parish towns in the country. In total, there are 47 linna, with "linn" in English meaning both "cities" and "towns". More than 70% of the population lives in towns. The 20 largest cities are listed below:

Religion

| Religion | 2000 Census[294] | 2011 Census[295] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| Orthodox Christians | 143,554 | 12.80 | 176,773 | 16.15 |

| Lutheran Christians | 152,237 | 13.57 | 108,513 | 9.91 |

| Baptists | 6,009 | 0.54 | 4,507 | 0.41 |

| Roman Catholics | 5,745 | 0.51 | 4,501 | 0.41 |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 3,823 | 0.34 | 3,938 | 0.36 |

| Old Believers | 2,515 | 0.22 | 2,605 | 0.24 |

| Christian Free Congregations |

223 | 0.02 | 2,189 | 0.20 |

| Earth Believers | 1,058 | 0.09 | 1,925 | 0.18 |

| Taara Believers | 1,047 | 0.10 | ||

| Pentecostals | 2,648 | 0.24 | 1,855 | 0.17 |

| Muslims | 1,387 | 0.12 | 1,508 | 0.14 |

| Adventists | 1,561 | 0.14 | 1,194 | 0.11 |

| Buddhists | 622 | 0.06 | 1,145 | 0.10 |

| Methodists | 1,455 | 0.13 | 1,098 | 0.10 |

| Other religion | 4,995 | 0.45 | 8,074 | 0.74 |

| No religion | 450,458 | 40.16 | 592,588 | 54.14 |

| Undeclared | 343,292 | 30.61 | 181,104 | 16.55 |

| Total1 | 1,121,582 | 100.00 | 1,094,564 | 100.00 |

1Population, persons aged 15 and older.

Estonia has a rich and diverse religious history, but in recent years it has become increasingly secular, with either a plurality or a majority of the population declaring themselves nonreligious in recent censuses, followed by those who identify as religiously "undeclared". The largest minority groups are the various Christian denominations, principally Lutheran and Orthodox Christians, with very small numbers of adherents in non-Christian faiths, namely Judaism, Islam and Buddhism. Other polls suggest the country is broadly split between Christians and the non-religious / religiously undeclared.

In ancient Estonia, prior to Christianization and according to Livonian Chronicle of Henry, Tharapita was the predominant deity for the Oeselians.[296]

Estonia was Christianised by the Catholic Teutonic Knights in the 13th century. The Protestant Reformation led to the establishment of the Lutheran church in 1686. Before the Second World War, Estonia was approximately 80% Protestant, overwhelmingly Lutheran,[297][298][299] followed by Calvinism and other Protestant branches. Many Estonians profess not to be particularly religious, because religion through the 19th century was associated with German feudal rule.[300] There has historically been a small but noticeable minority of Russian Old-believers near the Lake Peipus area in Tartu County.

Today, Estonia's constitution guarantees freedom of religion, separation of church and state, and individual rights to privacy of belief and religion.[301] According to the Dentsu Communication Institute Inc, Estonia is one of the least religious countries in the world, with 75.7% of the population claiming to be irreligious. The Eurobarometer Poll 2005 found that only 16% of Estonians profess a belief in a god, the lowest belief of all countries studied.[302] According to the Lutheran World Federation, the historic Lutheran denomination has a large presence with 180,000 registered members.[303]

New polls about religiosity in the European Union in 2012 by Eurobarometer found that Christianity is the largest religion in Estonia accounting for 45% of Estonians.[304] Eastern Orthodox are the largest Christian group in Estonia, accounting for 17% of Estonia citizens,[304] while Protestants make up 6%, and Other Christian make up 22%. Non believer/Agnostic account 22%, Atheist accounts for 15%, and undeclared accounts for 15%.[304]

The most recent Pew Research Center, found that in 2015, 51% of the population of Estonia declared itself Christian, 45% religiously unaffiliated—a category which includes atheists, agnostics and those who describe their religion as "Nothing in Particular", while 2% belonged to other faiths.[305] The Christians divided between 25% Eastern Orthodox, 20% Lutherans, 5% other Christians and 1% Roman Catholic.[306] While the religiously unaffiliated divided between 9% as atheists, 1% as agnostics and 35% as Nothing in Particular.[307]

Traditionally, the largest religious denomination in the country was Lutheranism, which was adhered to by 160,000 Estonians (or 13% of the population) according from 2000 census, principally ethnic Estonians. Other organisations, such as the World Council of Churches, report that there are as many as 265,700 Estonian Lutherans.[308] Additionally, there are between 8,000–9,000 members abroad. However, the 2011 census indicated that Eastern Orthodoxy had surpassed Lutheranism, accounting for 16.5% of the population (176,773 people).

Eastern Orthodoxy is practised chiefly by the Russian minority. The Estonian Orthodox Church, affiliated with the Russian Orthodox Church, is the primary Orthodox denomination. The Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church, under the Greek-Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarchate, claims another 20,000 members.

Roman Catholics are a small minority in Estonia. They are organised under the Latin Apostolic Administration of Estonia.

According to the census of 2000 (data in table to the right), there were about 1,000 adherents of the Taara faith[309][310][311] or Maausk in Estonia (see Maavalla Koda). The Jewish community has an estimated population of about 1,900 (see History of the Jews in Estonia), and the Muslim community numbers just over 1,400. Around 68,000 people consider themselves atheists.[312]

Languages

The official language, Estonian, belongs to the Finnic branch of the Uralic languages. Estonian is closely related to Finnish, spoken in Finland, across the other side of the Gulf of Finland, and is one of the few languages of Europe that is not of an Indo-European origin. Despite some overlaps in the vocabulary due to borrowings, in terms of its origin, Estonian and Finnish are not related to their nearest geographical neighbours, Swedish, Latvian, and Russian, which are all Indo-European languages.

Although the Estonian and Germanic languages are of very different origins, one can identify many similar words in Estonian and German, for example. This is primarily because the Estonian language has borrowed nearly one third of its vocabulary from Germanic languages, mainly from Low Saxon (Middle Low German) during the period of German rule, and High German (including standard German). The percentage of Low Saxon and High German loanwords can be estimated at 22–25 percent, with Low Saxon making up about 15 percent.

South Estonian languages are spoken by 100,000 people and include the dialects of Võro and Seto. The languages are spoken in South-Eastern Estonia, are genealogically distinct from northern Estonian: but are traditionally and officially considered as dialects and "regional forms of the Estonian language", not separate language(s).[313]

Russian is by far the most spoken minority language in the country. There are towns in Estonia with large concentrations of Russian speakers and there are towns where Estonian speakers are in the minority (especially in the northeast, e.g. Narva). Russian is spoken as a secondary language by forty- to seventy-year-old ethnic Estonians, because Russian was the unofficial language of the Estonian SSR from 1944 to 1991 and taught as a compulsory second language during the Soviet era. In 1998, most first- and second-generation industrial immigrants from the former Soviet Union (mainly the Russian SFSR) did not speak Estonian.[314] However, by 2010, 64.1% of non-ethnic Estonians spoke Estonian.[315] The latter, mostly Russian-speaking ethnic minorities, reside predominantly in the capital city of Tallinn and the industrial urban areas in Ida-Virumaa.

From the 13th to the 20th century, there were Swedish-speaking communities in Estonia, particularly in the coastal areas and on the islands (e.g., Hiiumaa, Vormsi, Ruhnu; in Swedish, known as Dagö, Ormsö, Runö, respectively) along the Baltic sea, communities which today have almost disappeared. The Swedish-speaking minority was represented in parliament, and entitled to use their native language in parliamentary debates.

From 1918 to 1940, when Estonia was independent, the small Swedish community was well treated. Municipalities with a Swedish majority, mainly found along the coast, used Swedish as the administrative language and Swedish-Estonian culture saw an upswing. However, most Swedish-speaking people fled to Sweden before the end of World War II, that is, before the invasion of Estonia by the Soviet army in 1944. Only a handful of older speakers remain. Apart from many other areas the influence of Swedish is especially distinct in the Noarootsi Parish of Lääne County where there are many villages with bilingual Estonian and/or Swedish names and street signs.[316][317]

The most common foreign languages learned by Estonian students are English, Russian, German, and French. Other popular languages include Finnish, Spanish, and Swedish.[318]

Education and science

The history of formal education in Estonia dates back to the 13th and 14th centuries when the first monastic and cathedral schools were founded.[319] The first primer in the Estonian language was published in 1575. The oldest university is the University of Tartu, established by the Swedish king Gustav II Adolf in 1632. In 1919, university courses were first taught in the Estonian language.

Today's education in Estonia is divided into general, vocational, and hobby. The education system is based on four levels: pre-school, basic, secondary, and higher education.[320] A wide network of schools and supporting educational institutions have been established. The Estonian education system consists of state, municipal, public, and private institutions. There are currently 589 schools in Estonia.[321]

According to the Programme for International Student Assessment, the performance levels of gymnasium-age pupils in Estonia is among the highest in the world: in 2010, the country was ranked 13th for the quality of its education system, well above the OECD average.[322] Additionally, around 89% of Estonian adults aged 25–64 have earned the equivalent of a high-school degree, one of the highest rates in the industrialised world.[323]

Academic higher education in Estonia is divided into three levels: bachelor's, master's, and doctoral studies. In some specialties (basic medical studies, veterinary, pharmacy, dentistry, architect-engineer, and a classroom teacher programme) the bachelor's and master's levels are integrated into one unit.[325] Estonian public universities have significantly more autonomy than applied higher education institutions. In addition to organising the academic life of the university, universities can create new curricula, establish admission terms and conditions, approve the budget, approve the development plan, elect the rector, and make restricted decisions in matters concerning assets.[326] Estonia has a moderate number of public and private universities. The largest public universities are the University of Tartu, Tallinn University of Technology, Tallinn University, Estonian University of Life Sciences, Estonian Academy of Arts; the largest private university is Estonian Business School.

The Estonian Academy of Sciences is the national academy of science. The strongest public non-profit research institute that carries out fundamental and applied research is the National Institute of Chemical Physics and Biophysics (NICPB; Estonian KBFI). The first computer centres were established in the late 1950s in Tartu and Tallinn. Estonian specialists contributed in the development of software engineering standards for ministries of the Soviet Union during the 1980s.[327][328] As of 2015, Estonia spends around 1.5% of its GDP on Research and Development, compared to an EU average of around 2.0%.[329]

Some of the best-known scientists related to Estonia include astronomers Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve, Ernst Öpik and Jaan Einasto, biologist Karl Ernst von Baer, Jakob von Uexküll, chemists Wilhelm Ostwald and Carl Schmidt, economist Ragnar Nurkse, mathematician Edgar Krahn, medical researchers Ludvig Puusepp and Nikolay Pirogov, physicist Thomas Johann Seebeck, political scientist Rein Taagepera, psychologist Endel Tulving and Risto Näätänen, semiotician Yuri Lotman.

According to New Scientist, Estonia will be the first nation to provide personal genetic information service sponsored by the state. They aim to minimise and prevent future ailments for those whose genes make them extra prone to conditions like adult-onset diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. The government plans to provide lifestyle advice based on the DNA for 100,000 of its 1.3 million citizens.[330]

Culture

The culture of Estonia incorporates indigenous heritage, as represented by the Estonian language and the sauna, with mainstream Nordic and European cultural aspects. Because of its history and geography, Estonia's culture has been influenced by the traditions of the adjacent area's various Finnic, Baltic, Slavic and Germanic peoples as well as the cultural developments in the former dominant powers Sweden and Russia.

Today, Estonian society encourages liberty and liberalism, with popular commitment to the ideals of the limited government, discouraging centralised power and corruption. The Protestant work ethic remains a significant cultural staple, and free education is a highly prized institution. Like the mainstream culture in the other Nordic countries, Estonian culture can be seen to build upon the ascetic environmental realities and traditional livelihoods, a heritage of comparatively widespread egalitarianism out of practical reasons (see: Everyman's right and universal suffrage), and the ideals of closeness to nature and self-sufficiency (see: summer cottage).

The Estonian Academy of Arts (Estonian: Eesti Kunstiakadeemia, EKA) is providing higher education in art, design, architecture, media, art history and conservation while Viljandi Culture Academy of University of Tartu has an approach to popularise native culture through such curricula as native construction, native blacksmithing, native textile design, traditional handicraft and traditional music, but also jazz and church music. In 2010, there were 245 museums in Estonia whose combined collections contain more than 10 million objects.[331]

Music

The earliest mention of Estonian singing dates back to Saxo Grammaticus Gesta Danorum (ca. 1179).[332] Saxo speaks of Estonian warriors who sang at night while waiting for a battle. The older folksongs are also referred to as regilaulud, songs in the poetic metre regivärss the tradition shared by all Baltic Finns. Runic singing was widespread among Estonians until the 18th century, when rhythmic folk songs began to replace them.

Traditional wind instruments derived from those used by shepherds were once widespread, but are now becoming again more commonly played. Other instruments, including the fiddle, zither, concertina, and accordion are used to play polka or other dance music. The kannel is a native instrument that is now again becoming more popular in Estonia. A Native Music Preserving Centre was opened in 2008 in Viljandi.[333]

The tradition of Estonian Song Festivals (Laulupidu) started at the height of the Estonian national awakening in 1869. Today, it is one of the largest amateur choral events in the world. In 2004, about 100,000 people participated in the Song Festival. Since 1928, the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds (Lauluväljak) have hosted the event every five years in July. The last festival took place in July 2019. In addition, Youth Song Festivals are also held every four or five years, the last of them in 2017.[334]

Professional Estonian musicians and composers such as Rudolf Tobias, Miina Härma, Mart Saar, Artur Kapp, Juhan Aavik, Aleksander Kunileid, Artur Lemba and Heino Eller emerged in the late 19th century. At the time of this writing, the most known Estonian composers are Arvo Pärt, Eduard Tubin, and Veljo Tormis. In 2014, Arvo Pärt was the world's most performed living composer for the fourth year in a row.[335]

In the 1950s, Estonian baritone Georg Ots rose to worldwide prominence as an opera singer.

In popular music, Estonian artist Kerli Kõiv has become popular in Europe, as well as gaining moderate popularity in North America. She has provided music for the 2010 Disney film Alice in Wonderland and the television series Smallville in the United States of America.

Estonia won the Eurovision Song Contest in 2001 with the song "Everybody" performed by Tanel Padar and Dave Benton. In 2002, Estonia hosted the event. Maarja-Liis Ilus has competed for Estonia on two occasions (1996 and 1997), while Eda-Ines Etti, Koit Toome and Evelin Samuel owe their popularity partly to the Eurovision Song Contest. Lenna Kuurmaa is a very popular singer in Europe, with her band Vanilla Ninja. "Rändajad" by Urban Symphony, was the first song in Estonian to chart in the UK, Belgium and Switzerland.

Literature

_by_Guenter_Prust.jpg)