Bothy

A bothy is a basic shelter, usually left unlocked and available for anyone to use free of charge. It was also a term for basic accommodation, usually for gardeners or other workers on an estate. Bothies are found in remote mountainous areas of Scotland, Northern England, Northern Ireland, Wales and the Isle of Man. They are particularly common in the Scottish Highlands, but related buildings can be found around the world (for example, in the Nordic countries there are wilderness huts). A bothy was also a semi-legal drinking den in the Isle of Lewis. These, such as Bothan Eòrapaidh, were used until recent years as gathering points for local men and were often situated in an old hut or caravan.

Etymology

The etymology of the word bothy is uncertain. Suggestions include a relation to both "hut" as in Irish bothán and Scottish Gaelic bothan or bothag;[1] a corruption of the Welsh term bwthyn, also meaning small cottage; and a derivation from Norse būð, cognate with English booth with a diminutive ending.

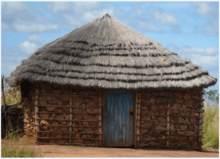

Character

Most bothies are ruined buildings which have been restored to a basic standard, providing a windproof and watertight shelter. They vary in size from little more than a large box up to two-storey cottages. They usually have designated sleeping areas, which commonly are either an upstairs room or a raised platform, thus allowing one to keep clear of cold air and draughts at floor height. No bedding, mattresses or blankets are provided. Public access to bothies is either on foot, by bicycle or boat.

Most bothies have a fireplace and are near a natural source of water. A spade may be provided to bury excrement.

Examples

There are thousands of examples to draw from. A typical Scottish bothy is the Salmon Fisherman's Bothy, Newtonhill, which is perched above the Burn of Elsick near its mouth at the North Sea.[2] Another Scottish example from the peak of the salmon fishing in the 1890s is the fisherman's bothy at the mouth of the Burn of Muchalls.[3][4] A further example is the Lairig Leacach Bothy in Lochaber, not far to the east of Fort William.

Estate examples

The best-known estate bothy is the one in the Royal Gardens at Windsor Castle, which could house about 25 people. It was used by the improver gardeners and disabled ex-servicemen who worked on the estate. Most reasonably-sized estates had a bothy, which housed single men only; in fact, if they got married, they had to give up the accommodation in the bothy. The most famous person to live in a bothy of this type was Percy Thrower when he worked in the Royal gardens. Another example of an estate bothy is the one at Horwood House, which held just five men. There is also one at Attingham Park which is being restored along with the walled gardens.

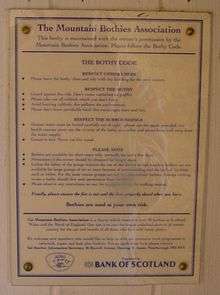

Bothy code

Because they are freely available to all, the continued existence of bothies relies on users helping look after them. Over the years, the Mountain Bothies Association has developed a Bothy Code[5] that sets out the main points users should respect:

- Bothies are used entirely at your own risk.

- Leave the bothy clean and tidy with dry kindling for the next visitors. Make other visitors welcome.[6]

- Report any damage to whoever maintains the bothy.[6] Take out all rubbish which you can't burn.[6] Avoid burying rubbish; this pollutes the environment.[6] Please do not leave perishable food as this attracts vermin.[6] Guard against fire risk and ensure the fire is out before you leave.[6] Make sure the doors and windows are properly closed when you leave.[6]

- If there is no toilet at the bothy please bury human waste out of sight and well away from the water supply; never use the vicinity of the bothy as a toilet.[6]

- Never cut live wood or damage estate property. Use fuel sparingly.[6]

- Large groups and long stays are to be discouraged – bothies are intended for small groups on the move in the mountains.[6]

- Respect any restrictions on use of the bothy, for example during stag stalking or at lambing time. Please remember bothies are available for short stays only. The owner's permission must be obtained if you intend an extended stay.[6]

- Because of overcrowding and lack of facilities, large groups (6 or more) should not use a bothy nor camp near a bothy without first seeking permission from the owner. Bothies are not available for commercial groups.[6]

Ownership

Bothies are usually owned by the landowner of the estate on which they stand, although the actual owner is rarely involved in any way, other than by permitting their continued existence, and by helping with transport of materials. Many are maintained by volunteers from the Mountain Bothies Association (MBA), a charity that looks after 97 bothies in Scotland, the north of England, and Wales.[7]

The location of these bothies can be found on the MBA website,[8] along with information on how people can help.[9]

In popular culture

The song Am Bothan a Bh'Aig Fionnghuala ("Fionghuala's Bothy") is a traditional song recorded by the Bothy Band in 1976.[10]

Bothy Culture is the second studio album by Scottish Celtic fusion artist Martyn Bennett. It was released in 1998.

Marion Zimmer Bradley used bothies as a pattern for shelters at Hellers mountains in her Darkover novels.

The narrator's bothy is the setting for much of the action in the 1996 suspense novel To the Hilt by Dick Francis.

A bothy is featured in the 2013 film Under the Skin.[11]

A bothy is featured in the 2012 video game Dear Esther, providing a crucial plot moment in the narration of the unknown main character.

The Key-Stone of the Bridge,[12] a novel and audiobook by Craig Meggy, is part homage to Robert Burns, set in Ben Alder Bothy.

The Scottish history podcast Stories of Scotland examines bothy culture, heritage and bothy ballads in its first episode.

See also

- Adirondack lean-to

- Bolt-hole

- Bothy band

- Bothy ballad

- But and ben – a simple two room cottage structure

- Castaway depot

- Cleit

- Mountain hut – building located in the mountains intended to provide food and shelter to mountaineers, climbers and hikers

- Shieling

- Vernacular architecture

- Wilderness hut – rent-free, open dwelling place for temporary accommodation, usually located in wilderness areas, national parks and along backpacking routes

References

- Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) © Oxford University Press 2009. Bothy.

- Brian H. Watt, Old Newtonhill and Muchalls, Stenlake Publishing, Glasgow (2005)

- C.M. Hogan, History of Muchalls Castle, Lumina Tech Press, Aberdeen (2005)

- Archibald Watt, Highways and Byways around Kincardineshire, Stonehaven Heritage Society (1985)

- http://www.mountainbothies.org.uk/Page.asp?page=bothy-code.asp

- Staff. "Bothy Code". mountainbothies.org.uk. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- MBA Website, "Mountain Bothies Association Website", (16 Sept 2009)

- "Mountain Bothy locations in England, Scotland and Wales". Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- "Help the Mountain Bothies Association repair and maintain a mountain bothy". Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- Lyr Req: Fionnghula (Bothy Band), the Mudcat Café

- "Behind the scenes of Under the Skin". Dazed. Mar 12, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- "The Keystone of the Bridge". The BeerMat BookShop. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mountain huts in the United Kingdom. |