Overseas censorship of Chinese issues

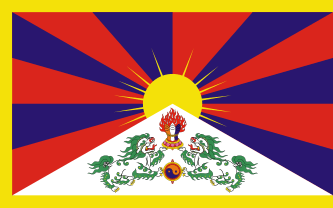

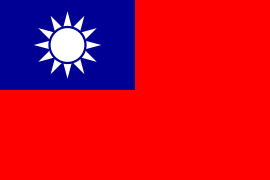

Overseas censorship of Chinese issues refers to censorship outside the People's Republic of China of topics considered sensitive by the ruling Communist Party of China. Censored topics include the political status of Taiwan, human rights in Tibet, Xinjiang re-education camps and the persecution of Uyghurs, the Tiananmen Square Massacre, the 2019–20 Hong Kong protests, the persecution of Falun Gong, and human rights in China in general.

| Part of a series on |

| Censorship by country |

|---|

|

| Countries |

| See also |

Censorship is undertaken by foreign companies wishing to do business in China, a growing phenomenon given the country's increasing economic prominence.[1][2][3] Companies seeking to avoid offending Chinese customers have engaged in self-censorship and, if accused of offending PRC government sensibilities, have performed "a 21st century kowtow" by posting apologies or making statements in support of government policy.[4] These actions reflect the companies' prioritisation of profit over business ethics, an impulse exploited by the PRC.[5]

The PRC government encourages its netizens to combat any perceived threats to the territorial integrity of China, including opposing any foreign expressions of support for protestors or perceived separatist movements, with the country's "Patriotic Education" system since the 1990s emphasising the dangers of foreign influence and the country's century of humiliation by outside powers.[6][7]

Censorship of overseas services is also undertaken by companies based in China, such as WeChat[8][9] and TikTok.[10] Chinese citizens living abroad as well as family residing in China have also been subject to threats to their employment, education, pension, and business opportunities if they engage in expression critical of the Chinese government or its policies.[11] With limited pushback by foreign governments and corporations, these issues have led to growing concern about self-censorship, compelled speech and a chilling effect on free speech in other countries.[12][13][14]

Censored topics

1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre

1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre Taiwan (including Taiwan independence movement, One Country on Each Side principle and other challenges to the One-China policy)

Taiwan (including Taiwan independence movement, One Country on Each Side principle and other challenges to the One-China policy) "Cults" such as Falun Gong

"Cults" such as Falun Gong Criticism of the Communist Party of China (including by the Chinese democracy movement)

Criticism of the Communist Party of China (including by the Chinese democracy movement)

Traditionally foreign companies wishing to do business in China needed to avoid references to the "Three Ts and the Two Cs": Tibet, Taiwan, the Tiananmen Square Massacre, "cults" such as Falun Gong, and criticism of the Chinese Communist Party.[15][16][17] This included related topics such as the Dalai Lama who the Chinese government considers a subversive Tibetan "splittist" and opposes any expressions of support from foreign governments or organisations.[18]

In the early 21st century, companies faced potential backlash on a broader range of issues relating to China, such as failing to include Hong Kong or Taiwan as part of China on their websites in violation of the One China Policy.[15] Further sensitive topics include: comments about leader Xi Jinping's weight,[19] including comparisons to rotund children's character Winnie the Pooh;[20] recognition of the Chinese government's Nine-Dash Line in the South China Sea dispute; the government's cultural genocide of Muslim Uyghurs and use of Xinjiang re-education camps;[21][22][23][24] and expressions of support for the 2019 Hong Kong protests.[25]

Notable examples

Academia

There is growing concern that the Chinese government is trying to silence its critics abroad, particularly in academic settings.[26] Historically censorship in China was contained within the country's borders, but following the ascension of Xi Jinping to General Secretary of the Communist Party of China in 2012, the focus has expanded to silencing dissent and criticism abroad, particularly in academia.[27]

There have been a number of incidents of Chinese students studying abroad in Western universities seeking to censor academics or students who espouse views inconsistent with the official Chinese Communist Party position. This includes intimidation and violence against Auckland University and University of Queensland protesters demonstrating in support of Hong Kong and Uyghurs,[28][29] challenging lecturers whose course materials do not follow the One China Policy by listing Hong Kong and Taiwan as separate countries,[30] and tearing down Lennon Walls in support of the Hong Kong democracy movement.[31] In 2019 the PRC Consul-General in Brisbane, Xu Jie, faced legal proceedings by a student who had organised a demonstration in support of the 2019 Hong Kong protests, alleging that Jie incited death threats by accusing him of "anti-Chinese separatism".[32]

Academics in British universities teaching on Chinese topics were also warned by the Chinese government to support the Chinese Communist Party or be refused entry to the country.[33] American universities have engaged in self-censorship on Chinese issues, including North Carolina State University cancelling a visit by the Dalai Lama in 2009 and University of Maryland Chinese student Yang Shuping apologising after harsh reaction to her commencement speech praising the "fresh air" of democracy and freedom in the United States.[34]

In November 2019, Columbia University cancelled a panel on human rights in China titled "Panopticism with Chinese Characteristics: Human rights violations by the Chinese Communist Party and how they affect the world."[35] Panel organizers criticized the university for allegedly compromising academic freedom by acquiescing to undue influence and threats of disturbances.[36]

Confucius Institutes

Concerns have been raised about the activities of Chinese government-funded Confucius Institutes in western universities, which are subject to rules set by Beijing-based Hanban that prevent the discussion of sensitive topics including Tibet, Tiananmen Square and Taiwan.[37] Institute learning materials also omit instances of humanitarian catastrophes under the Chinese Communist Party such as the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution.[38] Foreign Policy has likened Confucius Institutes to the "anaconda in the chandelier"; by their mere presence, they impact what staff and students feel safe discussing which leads to self-censorship.[38] American critics include FBI director Christopher Wray and politicians Seth Moulton, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio.[39]

Human Rights Watch considers the Confucius Institutes to be extensions of the Chinese government that prioritise political loyalty in their hiring decisions.[37][40]

Concerns arose following the 2014 Braga incident, in which materials for the Hanban-sponsored European Association for Chinese Studies 2014 conference in Braga were stolen and censored on the orders of Xu Lin, Director-General of Hanban and Chief Executive of the Confucius Institute Headquarters. Lin ordered the removal of references to Taiwanese academic institutions on the basis that they were "contrary to Chinese regulations",[41] which the Wall Street Journal described as a "bullying approach to academic freedom".[42] The incident led to a number of universities banning Confucius Institutes from their campuses,[43] including Stockholm University, Copenhagen Business School, Stuttgart Media University, the University of Hohenheim, the University of Lyon, the University of Chicago, Pennsylvania University, the University of Michigan and McMaster University.[44] Public schools in Toronto and New South Wales have also ceased their involvement in the program.[45][46]

In 2019 media reports emerged that four of the University of Queensland's courses relating to China had been funded by the local Confucius Institute, with the university's senate ending such deals in May 2019.[47] The university's vice-chancellor, Peter Høj, had previously been a senior consultant to Hanban.[47]

Several Confucius Institute contracts included clauses requiring the host university to follow Confucius Institute Headquarters' edicts on "teaching quality", raising concerns about foreign influence and academic freedom.[48] In 2020 the University of Melbourne and University of Queensland renegotiated their contracts to safeguard teaching autonomy in light of new Federal government laws requiring transparency on foreign influence.[49]

Chinese Students and Scholars Association

The Chinese Students and Scholars Association has branches in various overseas university campuses.[50] Each association branch is partly funded by, and reports back to, the local Chinese Embassy.[50] One of the aims of the Association is to "love the motherland".[50] There is a history of branches pressuring their host university to cancel talks relating to Tibet, the Chinese democracy movement, Uyghurs and the Hong Kong protests.[51]

The McMaster University branch in Canada had its club status revoked in 2019 after coordinating its opposition to a speech by Uyghur activist Rukiye Turdush with the local Chinese consulate, including sending back footage, in violation of student union rules.[51][52] The Adelaide University branch was deregistered for failing to follow democratic procedures.[50]

Airlines

In 2018, the Civil Aviation Administration of China sent letters to 44 international airlines demanding that they cease referring to Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau as separate countries on their websites, or risk being classified as "severely untrustworthy" and subject to sanctions.[53] Despite being criticised by the United States government as "Orwellian nonsense", all airlines complied.[54]

| Airline | Date | Details |

|---|---|---|

| American Airlines | July 2018 | The American carrier stopped listing Taiwan as a country on its website.[55] |

| Delta Airlines | July 2018 | The American carrier stopped listing Taiwan as a country on its website.[55] |

| Qantas | 4 June 2018 | The Australian carrier announced it would list Taiwan as a Chinese province rather than a separate country on its website,[56] after earlier stating that listing Taiwan and Hong Kong as countries on its website was an "oversight".[57] |

| United Airlines | July 2018 | The American carrier stopped listing Taiwan as a country on its website.[55] |

Film industry

Hollywood producers generally seek to comply with the Chinese government's censorship requirements in a bid to access the country's restricted and lucrative cinema market, with the second-largest box office in the world as of 2019.[58] This includes prioritising sympathetic portrayals of Chinese characters in movies, such as changing the villains in Red Dawn from Chinese to North Korean and making Chinese scientists the saviors of civilisation in the disaster film 2012.[58] In 2016, Marvel Entertainment attracted criticism for its decision to cast Tilda Swinton as "The Ancient One" in the film adaptation Doctor Strange, using a white woman to play a traditionally Tibetan character.[59][60] The film's co-writer, C. Robert Cargill, stated in an interview that this was done to avoid angering China:[61]

The Ancient One was a racist stereotype who comes from a region of the world that is in a very weird political place. He originates from Tibet, so if you acknowledge that Tibet is a place and that he's Tibetan, you risk alienating one billion people who think that that's bullshit and risk the Chinese government going, "Hey, you know one of the biggest film-watching countries in the world? We're not going to show your movie because you decided to get political."

Although Tibet was previously a cause célèbre in Hollywood, featuring in films including Kundun and Seven Years in Tibet, in the 21st century this is no longer the case.[62] Actor and high-profile Tibet supporter Richard Gere stated that he was no longer welcome to participate in mainstream Hollywood films after criticising the PRC government in 1993, acting in a 1997 film critical of the PRC's legal system (Red Corner), and calling for a boycott of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.[62][63]

International organisations

China strongly opposes the participation of Taiwan in international organisations as a violation of the One China Principle, and Taiwan may only participate in international bodies as "Chinese Taipei" or "Taiwan, China".[64][65][66]

Chinese Taipei was initially agreed under the Nagoya Resolution as the name to be used for the Taiwanese team at the Olympic Games since the 1980s. Under PRC pressure, Taiwan is referred to by other international organisations under different names, such as "Taiwan Province of China" by the International Monetary Fund and "Taiwan District" by the World Bank.[66] The PRC government has also pressured international beauty pageants including Miss World, Miss Universe and Miss Earth to only allow Taiwanese contestants competing under the designation "Miss Chinese Taipei" rather than "Miss Taiwan".[67][68]

Journalism

The PRC limits press freedom, with Xi Jinping telling state media outlets in 2016 that the Chinese Communist Party expects their "absolute loyalty".[69] In Hong Kong, inconvenient journalists face censorship by stealth through targeted violence, arrests, withdrawal of official advertising and/or dismissal.[70] Foreign journalists also face censorship given the ease with which their articles can be translated and shared across the country.[71]

Foreign journalists have reported rising official interference with their work, with a 2016 Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China survey finding 98% considered reporting conditions failed to meet international standards.[72] Interference includes withholding a visa to work in the country, harassment and violence by secret police and requiring press conference questions to be submitted for pre-screening.[72] Journalists also reported that local sources who speak to them face harassment, intimidation or detention by government officials, leading to a decreased willingness to cooperate with journalists.[72] Foreign journalists also face hacking of their email accounts by the PRC to discover their sources.[70]

The 2017 results indicated increasing violence and obstruction, with BBC reporter Matthew Goddard being punched by assailants who attempted to steal his equipment after he refused to show them footage taken.[73] In 2017, 73% of foreign journalists reported being restricted or prohibited from reporting in Xinjiang, up from 42% in 2016.[73] Journalists also reported more pressure from PRC diplomats on their headquarters to delete stories.[73]

Visas have been denied to a number of foreign journalists who wrote articles displeasing to the PRC government, such as the treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Expelled journalists include L'Obs reporter Ursula Gauthier, Al Jazeera journalist Melissa Chan in 2012 and Buzzfeed China bureau chief Megha Rajagopalan in 2018.[74]

As a result of increasing intimidation and the threat of being denied a visa, foreign journalists operating in China have increasingly engaged in self-censorship.[71] Topics avoided by journalists include Xinjiang, Tibet and Falun Gong.[71] Despite this, controversial stories continue to be published on occasion, such as the hidden wealth of political elites including Wen Jiabao[75] and Xi Jinping.[76][71]

The PRC government has also increasingly sought to influence public opinion abroad by hiring foreign reporters for state media outlets and paying for officially sanctioned "China Watch" inserts to be included in overseas newspapers including The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post and the Telegraph.[77]

Global political leadership

Since the Xi Jinping took leadership roles in foreign affairs for the People's Republic of China, the regime has adopted "a truculent posture"[78] in international relations, including what is said about China or its interests. The New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof has observed that "Xi doesn’t want to censor information just in his own country; he also wants to censor our own discussions in the West."[79] A key example is how Beijing opposes any meeting by foreign politicians with the Dalai Lama, even in a personal capacity.[80] However, it can be seen to handle different political leaders from different nations with different levels of control.

Australia

By November 2019 the PRC refused travel visas to Australian politicians Andrew Hastie and James Paterson after they criticised the Chinese Communist Party, its interference in Australian politics and its poor human rights record.[81] The Chinese Embassy stated that the pair needed to "repent" before they would be allowed into the country, which Hastie and Paterson refused.[82]

Canada

In 2015 the PRC detained then deported a Chinese-Canadian politician Richard Lee on the basis he had "endangered national security" by speaking out against PRC interference in Canadian politics.[83]

Germany

In 2016, the Chinese Ambassador to Germany "put massive pressure" on the Chairman of the Bundestag's Human Rights Committee, Michael Brand, a member of the conservative CDU party, in connection to his work exposing human rights abuses in Tibet. He later said, "Self-censorship is out of the question."[84]

In August 2019, a delegation of the German Bundestag due to visit China had all their visas blocked as one of its members, Margarete Bause, a Green, is a vocal supporter of the Muslim Uyghur minority. She believes that to be "an attempt at silencing parliamentarians who support human rights loudly and clearly."[85]

New Zealand

Jenny Shipley was Prime Minister of New Zealand and, after leaving politics, served as a director of China Construction Bank global board for six years from 2007 to 2013, then as Chair of China Construction Bank New Zealand up until 31 March 2019. In a case of what may be compelled speech, rather than restricted speech, the former Prime Minister appeared to write an opinion piece, "We need to learn to listen to China"[86] in the Communist Party controlled newspaper, People's Daily. It contained strong endorsements of current Chinese foreign policy, such as “The belt and road initiative (BRI) proposed by China is one of the greatest ideas we’ve ever heard globally. It is a forward-looking idea, and in my opinion, it has the potential to create the next wave of economic growth."[87] Ms Shipley later denied ever writing the article."[88]

In May 2020 efforts were made to silence criticism of China by Winston Peters, the current serving Foreign Minister of New Zealand. Matthew Hooton, a columnist at The New Zealand Herald threatened that Peters should be sacked if he insults China one more time.[89] Hooton did not disclose his conflict of interest, that he has been Mongolia's Honorary Consul to New Zealand since December 2017.

Sweden

On 15 November 2019 the Culture Minister of Sweden, Amanda Lind, went against the wishes of the Communist Party of China leadership and awarded Gui Minhai the PEN Tucholsky prize in absentia.[90] Mr Minhai, a Chinese-born Swedish citizen[91] had published poetry critical of communist China and was said to be preparing a book about the love life of Xi Jinping[92] before he was arrested by Chinese security agents on a train from Shanghai to Beijing.[93] Following the award, China's embassy in Stockholm released a statement saying that Minister Lind's attendance was "a serious mistake" and that "wrong deeds will only meet with bad consequences."[91] In the days afterwards China's Ambassador to Sweden, Gui Congyou, announced that "two large delegations of businessmen who were planning to travel to Sweden have cancelled their trip"[94] Ms Lind has already been threatened with a ban on entering China if she went ahead with the prize giving.[91] Later that month the Ambassador later gave an interview on Swedish public radio in which he said, "We treat our friends with fine wine, but for our enemies we have shotguns."[95]

United Kingdom

Also in 2019, the Chinese Ambassador to the United Kingdom warned that country's politicians against adopting a "colonial mindset" and observing limits in their comments on issues such as the Hong Kong protests and South China Sea dispute with China's neighbours.[96] China later suspended the Stock Connect link between the Shanghai and London stock exchanges, in part due to the United Kingdom's support for Hong Kong protesters.[97]

Publishing

Cambridge University Press drew criticism in 2017 for removing articles from its China Quarterly covering topics such as the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong and the Cultural Revolution to avoid having its Chinese operations shut down.[98][99] Springer Nature also acceded to Chinese demands to censor articles relating to Chinese politics, Taiwan, Tibet and human rights.[100][101]

In 2017 the Australian publisher Allen & Unwin refused to publish Clive Hamilton's book Silent Invasion about growing Chinese Communist Party influence in Australia, fearing potential legal action from the Chinese government or its local proxies under the auspices of the United Front Work Department.[102][103]

Publishers using Chinese printers have also been subject to local censorship, even for books not intended for sale in China.[104] Books with maps face particular scrutiny, with one Victoria University Press book Fifteen Million Years in Antarctica required to remove the English term "Mount Everest" in favour of the Chinese equivalent "Mount Qomolangma".[104] This has led publishers to consider printers in alternative countries, such as Vietnam.[104]

Whistleblower Edward Snowden criticised Chinese censors for removing passages in the translated version of his book Permanent Record, in which passages about authoritarianism, democracy, freedom of speech and privacy were removed.[105]

Technology companies

Several American technology companies cooperate with Chinese government policies, including internet censorship, such as helping authorities build the Great Firewall of China to restrict access to sensitive information.[106] Yahoo! drew controversy after supplying the personal data of its user Shi Tao to the PRC government, resulting in Tao's 10 year imprisonment for "leaking state secrets abroad".[107] In 2006 Microsoft, Google, Yahoo! and Cisco appeared before a congressional inquiry into their Chinese operations where their cooperation with censorship and privacy breaches of individuals faced criticism.[108]

The Chinese government is increasingly pressuring overseas individuals and companies to cooperate with its censorship model, including in relation to overseas communications made by foreign people for non-Chinese audiences.[109]

Other instances

The table below includes notable instances outside China where a government, company or other entity has censored a China-related issue.

| Entity | Date | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Microsoft | 4 January 2006 | The company removed the blog of Chinese journalist Zhao Jing from its MSN Spaces website, which was hosted on servers based in the United States.[110] |

| Nasdaq | February 2007 | In 2007 Nasdaq's Chinese representative Laurence Pan was detained and interrogated about access to its exchange by New Tang Dynasty Television, a Falun Gong-linked media organisation. That organisation was subsequently denied access by Nasdaq.[111] |

| Eutelsat | 2008 | The media company cut New Tang Dynasty Television's signal to "show a good gesture to the Chinese government".[111] |

| Government of Vietnam | 11 November 2011 | The country imprisoned two Falun Gong activists who transmitted radio messages into China for "illegal transmission of information on a telecommunications network".[112] |

| Bing | 12 February 2014 | The search engine censored simplified Chinese language results for users in the United States for search terms including "Dalai Lama", "June 4 incident", Falun Gong and anti-censorship tool Freegate.[113] |

| 4 June 2014 | The company blocked users outside China from viewing content posted by Chinese users that is restricted by the Chinese government.[114] | |

| Chou Tzu-yu | 16 January 2016 | The Taiwan-born K-pop singer issued an apology for being pictured with the Taiwanese flag, following sustained online attacks on her and her band Twice by Chinese internet users.[115] |

| Microsoft | 22 November 2016 | The company programmed its Chinese language artificial intelligence-based chatbot Xiaobing to avoid discussing sensitive topics such as Tiananmen Square.[116] |

| Apple Inc. | 7 January 2017 | The company removed the New York Times app from its Chinese app store following Chinese government advice that it violated local regulations.[117] This led to the company being accused by online advocates of "globalising Chinese censorship".[118] |

| Allen & Unwin | 12 November 2017 | The Australian publisher refused to publish Clive Hamilton's book Silent Invasion about growing Chinese Communist Party influence in Australia on the basis that it feared legal action from the Chinese government or its proxies.[102] |

| Marriott International | 12 January 2018 | The hotel chain issued an apology and was ordered by the Cyberspace Administration of China to shut its Chinese website and booking application for one week after an employee managing its social media "liked" a tweet thanking the company for listing Tibet as a country on a customer questionnaire alongside Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau.[119] After the Shanghai Municipal Tourism Administration ordered the company to "seriously deal with the people responsible", it dismissed the employee.[120][121] |

| Mercedes Benz | 7 February 2018 | The German car maker issued an apology on Weibo for "hurting the feelings" of the people of China after quoting the Dalai Lama on Instagram, a service banned in China.[122] The company also sent a formal letter to the Chinese Ambassador in Germany, stating that it had "no intention of questioning or challenging in any manner China's sovereignty or territorial integrity."[123] |

| Gap Inc. | 15 May 2018 | The company apologised after photographs circulated of a t-shirt sold in Canada that featured a map of China omitting Taiwan, Tibet and China's South China Sea territorial claim.[124][125] |

| TikTok | 25 September 2019 | The Guardian revealed the TikTok app's moderation guidelines prohibiting content mentioning Tiananmen Square, Tibetan independence and Falun Gong.[126] Content criticising the Chinese government's persecution of ethnic minorities or mentioning the 2019 Hong Kong protests are also removed.[10] ByteDance, the app's Beijing-based owner responded to the media reports by stating that the leaked moderation guidelines were "outdated" and that it had introduced localised guidelines for different countries.[126] Searches relating to Hong Kong on the app found no content referencing the ongoing protests.[127] Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg also criticised the platform for its censorship of Hong Kong protest content, asking "is this the internet we want?"[128] |

| Apple Inc. | 2 October 2019 | The company banned the HKmap.live app from its App Store, which allowed for crowd-sourced information about the location of protestors and police in Hong Kong.[129] It did so on the basis that the app "allowed users to evade law enforcement".[130] The same month Apple banned the Quartz app due to its coverage of the 2019 Hong Kong protests.[131] |

| Sheraton | 3 October 2019 | The chain's Stockholm hotel cancelled a celebration of Taiwan's Double Ten national holiday after pressure from the Chinese Ambassador; it was moved to a local museum.[132][133] |

| Tiffany & Co. | 7 October 2019 | The jewellery company deleted a photo on one of its social media accounts of a woman covering one eye, which a number of Chinese internet users considered to evoke the image of a Hong Kong protestor who had been shot in one eye.[15] |

| Activision Blizzard | 8 October 2019 | In the Blitzchung controversy, the company withdrew the prize from the winner of an online game tournament after he wore a mask and spoke in support of the 2019 Hong Kong protests in a post-game interview, stating "Liberate Hong Kong, the revolution of our times".[134] The company is partly owned by Tencent.[15] |

| ESPN | 8 October 2019 | Chuck Salituro, the channel's senior news director, sent an internal memo to staff banning any discussion of political issues concerning China or Hong Kong when covering the controversy of Daryl Morey's tweet in support of Hong Kong protestors.[135] |

| Wells Fargo Center, Philadelphia | 9 October 2019 | Center staff removed fans shouting "Free Hong Kong" at a pre-season game between the Philadelphia 76ers and Guangzhou Loong Lions.[136] |

| National Basketball Association | 10 October 2019 | CNN journalist Christina Macfarlane was shut down and had her microphone removed at an NBA press conference after asking players James Harden and Russell Westbrook if they would feel differently about speaking out in future following the NBA's censorship of comments that are critical of China.[137] |

| Christian Dior | 17 October 2019 | Christian Dior issued a public apology on its Weibo account for displaying a map during a university presentation that did not include Taiwan.[138] |

| Maserati | 25 October 2019 | Maserati asked a local car dealership to cut all ties with Taiwan's Golden Horse Film Festival and Awards and stated that it "firmly upholds the one-China principle."[139] |

| Shutterstock | 6 November 2019 | In November 2019, The Intercept reported that Shutterstock censors certain search results for users in mainland China.[140][141] The six banned terms were "President Xi", "Chairman Mao", "Taiwan flag", "dictator", "yellow umbrella" and "Chinese flag" and variations.[142] After 180 employees (one-fifth of the workforce) signed a petition opposing the censorship, company executive Stan Pavlovsky told staff that anyone opposed to its self-censorship was free to resign.[142] |

| 25 November 2019 | Reports emerged that China-based WeChat was censoring users in the United States communicating about Hong Kong politics.[143] | |

| DC Comics | 27 November 2019 | DC Comics removed a promotional Batman poster after it triggered criticism from mainland China netizens that its imagery, featuring Batwoman throwing a molotov cocktail beside the words "The future is young", was sympathetic to Hong Kong protesters.[144][145] |

| TikTok | 28 November 2019 | The platform apologised after blocking American user Feroza Aziz following a video which she made drawing attention to the mistreatment of Muslims in the Xinjiang re-education camps, which she disguised as a make-up tutorial to evade censorship.[146] |

| Condé Nast | 6 December 2019 | GQ magazine removed Xi Jinping from its "Worst Dressed" list on its website along with the caption: "It is not Hong Kong's courageous freedom fighters that Xi Jinping should have a problem with. It's his tailor. Xi gets totalitarian style cues from his hero, the mass murderer Chairman Mao, who enforced a dour and plain dress code for the Communist Party."[147] |

| Arsenal F.C. | 15 December 2019 | Arsenal footballer Mesut Özil posted a poem on his social media account denouncing China's treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang re-education camps and the silence of Muslim countries on the issue.[148][149][150] Arsenal later released a statement distancing itself from the comments.[151] China's state broadcaster China Central Television responded two days later by removing the match between Arsenal and Manchester City from its schedule.[152][153] |

| World Health Organisation | 28 March 2020 | Senior advisor Bruce Aylward faced criticism for saying he could not hear a question from RTHK journalist Yvonne Tong about whether Taiwan could join the WHO, asking her to move onto the next question then terminating the interview when she repeated it.[154] The World Health Organisation has also faced criticism for downplaying Taiwan's success in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.[154] |

| European Union | 24 April 2020 | The organisation agreed to censor references to the Chinese origins of the COVID-19 pandemic,[155] with research suggesting that self-censorship on sensitive topics that may offend the PRC is commonplace.[156] |

| YouTube | 26 May 2020 | Reports emerged that since October 2019, comments posted with the Chinese characters 共匪 (gòngfěi or "communist bandit", an insult dating back to China's Nationalist government) or 五毛 (wǔmáo or "50 Cent Party", referring to State-sponsored commentators) were being automatically deleted within 15 seconds.[157] |

| Zoom | 12 June 2020 | The videoconferencing provider confirmed that it had suspended the accounts of users based in the United States and Hong Kong who booked meeting to discuss the Tiananmen Square Massacre and Hong Kong protests following PRC Government complaints, and that it would seek to limit such actions to people based in the mainland in future.[158] |

Opposition and resistance

In 2010 Google opposed China's censorship policies, ultimately leaving the country.[159] By 2017 the company had dropped its opposition, including planning a Chinese Communist Party-approved censored search engine named Project Dragonfly.[160] Work on the project was terminated in 2019.[161]

In 2019 Comedy Central's animated sitcom South Park released the episode "Band in China", which satirised the self-censorship of Hollywood producers to suit Chinese censors and featured one character yelling "Fuck the Chinese government!".[162][163] This was followed by a mock apology from the show's creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone, which also made light of a recent controversy involving the NBA's alleged appeasement of Chinese government censorship:[162]

Like the NBA, we welcome the Chinese censors into our homes and into our hearts. We too love money more than freedom and democracy. Tune into our 300th episode this Wednesday at 10! Long live the great Communist Party of China. May the autumn's sorghum harvest be bountiful. We good now China?

The show was banned in mainland China following the incident.[162] Protesters in Hong Kong screened the episode on the city's streets.[164] The musician Zedd was banned from China after liking a tweet from South Park.[165]

See also

- Censorship in China

- Censorship in Hong Kong

- Corporate censorship

- Censorship by Apple#China

- Cisco Systems#Censorship in China

- Censorship by Google#China

- Criticism of Microsoft#Censorship in China

- Criticism of Myspace#MySpace China

- National Basketball Association criticisms and controversies#2019 Hong Kong protests

- Skype#Service in the People's Republic of China

- Criticism of Yahoo!#Work in the People's Republic of China

References

- "NBA-China standoff raises awareness of threat of Chinese censorship". Axios. 9 October 2019. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Birtles, Bill (10 October 2019). "Cancellations, apologies and anger as China's nationalists push the boundaries of curtailing free speech". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Pinon, Natasha (11 October 2019). "Here's a growing list of companies bowing to China censorship pressure". Mashable. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Mazumdaru, Srinivas (11 October 2019). "Western firms kowtow to China's increasing economic clout". DW.com. Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Tufekci, Zeynep (15 October 2019). "Are China's Tantrums Signs of Strength or Weakness?". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Dunn, Will (21 October 2019). "How Chinese censorship became a global export". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Yuan, Li (11 October 2019). "China's Political Correctness: One Country, No Arguments". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "How China's censorship machine crosses borders — and into Western politics". Human Rights Watch. 20 February 2019. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Blackwell, Tom (December 4, 2019). "Censored by a Chinese tech giant? Canadians using WeChat app say they're being blocked". National Post. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- O'Brien, Danny (10 October 2019). "China's Global Reach: Surveillance and Censorship Beyond the Great Firewall". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Raleigh, Helen (5 June 2019). "Chinese Censors Crack Down On Foreigners' Speech Online". The Federalist. FDRLST Media. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Mazza, Michael (31 July 2018). "China's airline censorship over Taiwan must not fly". Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Stone Fish, Isaac (11 October 2019). "Perspective: How China gets American companies to parrot its propaganda". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Anderson, Mae (9 October 2019). "U.S. companies walk a fine line when doing business with China". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Qin, Amy; Creswell, Julie (8 October 2019). "China Is a Minefield, and Foreign Firms Keep Hitting New Tripwires". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Watts, Jonathan (25 January 2006). "Backlash as Google shores up great firewall of China". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Baron, Dennis (2012). A Better Pencil: Readers, Writers, and the Digital Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 212. ISBN 9780199914005.

- "Analysis: Why the Dalai Lama angers China". CNN.com. 18 February 2010. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "9-year-old asks Chinese President Xi Jinping to lose weight, letter goes viral". Young Post. South China Morning Post. 18 December 2014. Archived from the original on 3 April 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Romano, Aja (24 October 2019). "China reportedly censored PewDiePie for supporting the Hong Kong protests. He's not the only one". Vox. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Hayes, Anna (2 October 2014). "What China's censors don't want you to read about the Uyghurs". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Leibold, James (24 July 2019). "Despite China's denials, its treatment of the Uyghurs should be called what it is: cultural genocide". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Handley, Erin; Mantesso, Sean (10 November 2019). "Uyghurs are facing 'cultural genocide' in China but in Australia they're fighting for their history". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Ramzy, Austin (5 January 2019). "China Targets Prominent Uighur Intellectuals to Erase an Ethnic Identity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Xu, Vicky Xiuzhong (1 October 2019). "China's Youth Are Trapped in the Cult of Nationalism". Foreign Policy. Slate Group. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Zhang, Tao (4 January 2018). "How can scholars tackle the rise of Chinese censorship in the West?". Times Higher Education. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Maxwell, Daniel (5 August 2019). "Academic censorship in China is really a global issue". Study International. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Raleigh, Helen (2 August 2019). "How China Tries To Take Its Totalitarian Social Control Tactics Global". The Federalist. FDRLST Media. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Garcia, Jocelyn (24 July 2019). "'I was shocked': UQ protest against Chinese government turns violent". Brisbane Times. Nine Newspapers. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Ho, Gwyneth (5 September 2017). "Australia universities caught in China row". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- "'Lennon wall' incidents a sign of 'anxiety': professor - Taipei Times". Taipei Times. 12 October 2019. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Doherty, Ben (23 October 2019). "Queensland student sues Chinese consul general, alleging he incited death threats". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Das, Shanti (23 June 2019). "Beijing leans on UK dons to praise Communist Party and avoid 'the three Ts — Tibet, Tiananmen and Taiwan'". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Stone Fish, Isaac (4 September 2018). "The Other Political Correctness". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Zahneis, Megan (2019-11-19). "Columbia U. Canceled an Event on Chinese Human-Rights Violations. Organizers See a University Bowing to Intimidation". The Chronicle of Higher Education. ISSN 0009-5982. Archived from the original on 2019-11-23. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- Zahneis, Megan (2019-11-23). "Why did Columbia cancel Chinese rights violations event?". The Chronicle of Higher Education. ISSN 0009-5982. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- Jakhar, Pratik (7 September 2019). "Is China's network of cultural clubs pushing propaganda?". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Fulda, Andreas (15 October 2019). "Chinese Propaganda Has No Place on Campus". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Redden, Elizabeth (9 January 2019). "Colleges move to close Chinese government-funded Confucius Institutes amid increasing scrutiny". Inside Higher Ed. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "World Report 2019: Rights Trends in China". Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch. 28 December 2018. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Redden, Elizabeth (6 August 2014). "Accounts of Confucius Institute-ordered censorship at Chinese studies conference". Inside Higher Ed. Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "Beijing's Propaganda Lessons". Wall Street Journal. 7 August 2014. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Wu, Yan; Wang, Qi; Liu, Nian Cai (2018). World-Class Universities: Towards a Global Common Good and Seeking National and Institutional Contributions. BRILL. p. 206. ISBN 978-90-04-38963-2.

- Benakis, Theodoros (20 February 2019). "Confucius Institutes under scrutiny in UK". European Interest. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Baker, Jordan; Chung, Laura (22 August 2019). "NSW schools to scrap Confucius Classroom program after review". The Sydney Morning Herald. Nine Newspapers. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Moczulski, J. P. (29 October 2014). "TDSB votes to officially cut ties with Confucius Institute". Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Rubinsztein-Dunlop, Sean (15 October 2019). "The Chinese government co-funded at least four University of Queensland courses". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Hunter, Fergus (24 July 2019). "Universities must accept China's directives on Confucius Institutes, contracts reveal". The Sydney Morning Herald. Nine Newspapers. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Hunter, Fergus (10 March 2020). "Universities rewrite Confucius Institute contracts amid foreign influence scrutiny". The Sydney Morning Herald. Nine Newspapers. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Christodoulou, Mario; Rubinsztein-Dunlop, Sean; Koloff, Sashka; Day, Lauren; Bali, Meghna (13 October 2019). "'Universities have a really serious issue on their hands': Chinese student group's deep links to Beijing revealed". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Churchill, Owen (26 September 2019). "Chinese students' group in Canada loses status after Uygur speaker protest". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Chase, Steven (26 September 2019). "McMaster student union strips Chinese club's status amid allegations group is tool of Chinese government". Globe and Mail. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Xu, Vicky Xiuzhong (7 May 2018). "'Orwellian nonsense': China retaliates after US slams territory warning to international airlines". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Birtles, Bill (25 July 2018). "Last remaining US airlines give in to Chinese pressure on Taiwan". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Piacenza, Joanna (15 October 2019). "Amid NBA-China Clash, U.S. Consumers Indifferent Toward Global Business Dealings". Morning Consult. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Qantas to refer to Taiwan as a territory, not a nation, following Chinese demands". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 4 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Zhou, Christina; Mo, Xiaoning (15 January 2018). "Qantas admits 'oversight' in listing Taiwan, Hong Kong as countries". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Whalen, Jeanne (8 October 2019). "China lashes out at Western businesses as it tries to cut support for Hong Kong protests". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Shaw-Williams, Hannah (20 April 2016). "Doctor Strange's Erasure Of Tibet Is A Political Statement". ScreenRant. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Bisset, Jennifer (November 1, 2019). "Marvel is censoring films for China, and you probably didn't even notice". CNET. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- Clymer, Jeremy (24 April 2016). "Doctor Strange Writer Says Ancient One Was Changed To Avoid Upsetting China". ScreenRant. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Steger, Isabella (28 March 2019). "Why it's so hard to keep the world focused on Tibet". Quartz. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Siegel, Tatiana (18 April 2017). "Richard Gere's Studio Exile: Why His Hollywood Career Took an Indie Turn". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "What is "Chinese Taipei"?". The Economist. 9 April 2018. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Winkler, Sigrid (20 June 2012). "Taiwan's UN Dilemma: To Be or Not To Be". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Fish, Isaac Stone. "Stop Calling Taiwan a 'Renegade Province'". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "Taiwanese beauty queen kicked out of Miss Earth pageant for refusing to change 'Taiwan ROC' sash to 'Chinese Taipei'". Shanghaiist. 23 November 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Miss Taiwan in beauty pageant shocker". Taipei Times. 11 July 2003. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Xi Jinping asks for 'absolute loyalty' from Chinese state media". The Guardian. Associated Press. 19 February 2016. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Bennett, Philip; Naim, Moises (February 2015). "21st-century censorship". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Parker, Emily (9 December 2013). "China's government Is Scaring Foreign Journalists Into Censoring Themselves". The New Republic. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Greenslade, Roy (15 November 2016). "Foreign journalists working in China face increased harassment". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Foreign journalists in China complain of abuse from officials". South China Morning Post. 30 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Wang, Maya (28 August 2018). "Another journalist expelled – as China's abuses grow, who will see them?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Barboza, David (25 October 2012). "Billions in Hidden Riches for Family of Chinese Leader". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Xi Jinping Millionaire Relations Reveal Fortunes of Elite". Bloomberg.com. 29 June 2012. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Lim, Louisa; Bergin, Julia (7 December 2018). "Inside China's audacious global propaganda campaign". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Christensen, Thomas J. (2011-03-11). "The Advantages of an Assertive China". ISSN 0015-7120. Archived from the original on 2019-11-21. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- Kristof, Nicholas (2019-10-09). "Opinion | Let's Not Take Cues From a Country That Bans Winnie the Pooh". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2020-03-25. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- Lau, Stuart (21 October 2017). "Chinese official attacks foreign leaders for meeting Dalai Lama". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Greenbank, political reporters Amy; Beech, ra (15 November 2019). "Liberal MPs banned from travelling to China for study trip". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Dalzell, Stephanie; Probyn, Andrew (17 November 2019). "Hastie and Paterson defiant in the face of China's calls for repentance". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Cooper, Sam (29 November 2019). "B.C. politician breaks silence: China detained me, is interfering 'in our democracy'". Global News. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "China refuses entry to German chair of human rights committee | DW | 11.05.2016". DW.COM. Archived from the original on 2018-09-21. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "China denies entry to German Greens party | DW | 04.08.2019". DW.COM. Archived from the original on 2019-08-06. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- "'We need to learn to listen to China' - People's Daily Online". en.people.cn. Archived from the original on 2019-10-25. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Roy, Eleanor Ainge (2019-02-20). "New Zealand former PM denies writing glowing pro-China piece for Beijing paper". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2019-10-22. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- "Former NZ PM resigns from China Construction Bank unit". South China Morning Post. 2019-03-04. Archived from the original on 2020-05-03. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- matthew.hooton@exceltium.com, Matthew Hooton (2020-05-18). "Matthew Hooton: Winston Peters should be sacked over China controversy". NZ Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 2020-05-19. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- "China cancels Sweden business trips after prize for dissident". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2020-03-16. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- "China, Sweden escalate war of words over support for detained bookseller". Reuters. 2019-11-16. Archived from the original on 2020-02-26. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- "Hong Kong bookseller Gui Minhai jailed for 10 years in China". the Guardian. 2020-02-25. Archived from the original on 2020-04-29. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- Phillips, Tom (2018-02-22). "'A very scary movie': how China snatched Gui Minhai on the 11.10 train to Beijing". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2020-05-13. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- "China cancels Sweden business trips after prize for dissident". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2020-03-16. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- "How Sweden copes with Chinese bullying". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 2020-04-22. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- Defence, Dan Sabbagh; editor, security (9 September 2019). "Avoid irresponsible remarks on Hong Kong, China warns UK MPs". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Exclusive: China halts British stock link over political tensions - sources". Reuters. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Johnson, Ian (18 August 2017). "Cambridge University Press Removes Academic Articles on Chinese Site". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Phillips, Tom (19 August 2017). "Cambridge University Press accused of 'selling its soul' over Chinese censorship". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Hernández, Javier C. (1 November 2017). "Leading Western Publisher Bows to Chinese Censorship". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- "Chinese censors issue fresh warning to foreign publishers". South China Morning Post. 6 November 2017. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- McKenzie, Nick; Baker, Richard (12 November 2017). "Free speech fears after book critical of China is pulled from publication". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Williams, Jacqueline (20 November 2017). "Australian Furor Over Chinese Influence Follows Book's Delay". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 September 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Lew Linda (25 August 2019). "How Chinese censorship laws hit foreign publishers". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Kuo, Lily (12 November 2019). "Edward Snowden says autobiography has been censored in China". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- James, Randy (18 March 2009). "A Brief History of Chinese Internet Censorship". Time Magazine. TimeWarner. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- MacKinnon, Rebecca. "Shi Tao, Yahoo!, and the lessons for corporate social responsibility" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "Race to the Bottom - Corporate Complicity in Chinese Internet Censorship". Human Rights Watch. 9 August 2006. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Mozur, Paul (2 March 2018). "China Presses Its Internet Censorship Efforts Across the Globe". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Donoghue, Andrew (4 January 2006). "Microsoft censors Chinese blogger". CNET. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Cook, Sarah (28 October 2013). "How Chinese censorship is reaching overseas". Global Public Square. CNN. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Chi, Quynh; Ha, Viet; Lipes, Joshua (11 November 2011). "Under Fire Over Falun Gong Jailing". Radio Free Asia. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Rushe, Dominic (11 February 2014). "Bing censoring Chinese language search results for users in the US". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Branigan, Tania (4 June 2014). "LinkedIn under fire for censoring Tiananmen Square posts". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Buckley, Chris; Ramzy, Austin (16 January 2016). "Singer's Apology for Waving Taiwan Flag Stirs Backlash of Its Own". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Rudolph, Josh (22 November 2016). "Microsoft's Chinese Chatbot Encounters Sensitive Words". China Digital Times. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Haas, Benjamin (5 January 2017). "Apple removes New York Times app in China". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Chan, Melissa (6 January 2017). "Apple is not the only tech company kowtowing to China's censors". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Haas, Benjamin (12 January 2018). "Marriott apologises to China over Tibet and Taiwan error". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- MacLellan, Lila (4 March 2018). "An hourly Marriott employee got fired for liking a tweet". Quartz at Work. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Matyszczyk, Chris (7 March 2018). "Here's What Happened After a Marriott Employee Liked a Congratulatory Tweet (Clue: He Doesn't Work for Marriott Anymore)". Inc.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Mercedes apologises to China after quoting Dalai Lama". The Telegraph. 7 February 2018. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Mercedes-Benz Offers Second Apology to China Over Dalai Lama Quote". Sputnik News. 8 February 2018. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Gap apologizes to China over map on T-shirt that omits Taiwan, South China Sea". Washington Post. 14 May 2018. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Gap apologises for T-shirt with 'incorrect' map of China". South China Morning Post. Reuters. 15 May 2018. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Hern, Alex (25 September 2019). "Revealed: how TikTok censors videos that do not please Beijing". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Harwell, Drew. "TikTok's Beijing roots fuel censorship suspicion as it builds a huge U.S. audience". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Holmes, Aaron (18 October 2019). "Mark Zuckerberg just slammed China for allegedly censoring Hong Kong protest videos on TikTok: 'Is that the internet we want?'". Business Insider Australia. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- McCarthy, Kieren (2 October 2019). "Here's that hippie, pro-privacy, pro-freedom Apple y'all so love: Hong Kong protest safety app banned from iOS store". The Register. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- "Apple bans Hong Kong protest location app". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 3 October 2019. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Ivanova, Irina (October 10, 2019). "Apple pulls Quartz news app from its China store after Hong Kong coverage". CBS News. Archived from the original on October 13, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- Emanuelsson, Eric (3 October 2019). "Kinas ambassad pressade hotell att inte låta Taiwan-representanter fira sin nationaldag". Expressen (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Strong, Matthew (5 October 2019). "China forces Taiwan National Day reception out of Stockholm Sheraton". Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Pandey, Erica (9 October 2019). "NBA-China standoff raises awareness of threat of Chinese censorship". Axios. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Wagner, Laura (8 October 2019). "Internal Memo: ESPN Forbids Discussion Of Chinese Politics When Discussing Daryl Morey's Tweet About Chinese Politics". Deadspin. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Ileto, Christie (9 October 2019). "Sixers fan supporting Hong Kong ejected from preseason game amid NBA-China controversy". 6abc Philadelphia. WPVI-TV Philadelphia. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Nash, Charlie (10 October 2019). "'Chilling': CNN Reporter Shut Down For Asking NBA's Harden and Westbrook About China Censorship". Mediaite. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Valinsky, Jordan (October 17, 2019). "Christian Dior apologizes to China for not including Taiwan in a map". CNN. Archived from the original on October 17, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- Griffiths, James (October 25, 2019). "Maserati distances itself from Asian 'Oscars' in Taiwan under pressure from China". CNN. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- Biddle, Sam (November 6, 2019). "Shutterstock Employees Fight Company's New Chinese Search Blacklist". The Intercept. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Ingram, David (February 27, 2020). "Chinese censorship or 'work elsewhere': Inside Shutterstock's free-speech rebellion". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Ingram, David (28 February 2020). "'Management doesn't listen': Inside the employee-led revolt at Shutterstock". NBC News. NBC Universal. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Schiffer, Zoe (25 November 2019). "WeChat keeps banning Chinese Americans for talking about Hong Kong". The Verge. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Davis, Rebecca (November 28, 2019). "DC Comics Comes Under Fire for Deleting Batman Poster That Sparked Chinese Backlash". Variety. Archived from the original on November 28, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- Flood, Alison (2019-11-29). "DC drops Batman image after claims it supports Hong Kong unrest". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2019-11-29. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- Kuo, Lily (28 November 2019). "TikTok sorry for blocking teenager who disguised Xinjiang video as make-up tutorial". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Di Stefano, Mark (December 6, 2019). "British GQ Put China's President And Thailand's King On Its "Worst Dressed" List, Then Removed Them Online So As Not To Cause Offence". BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- Vigdor, Neil (2019-12-15). "Soccer Broadcast Pulled After Arsenal Star Mesut Özil Criticized China". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2019-12-17. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "China TV pulls Arsenal game after Mesut Özil's Uighur comments". DW.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- "Chinese TV pulls Arsenal match after Ozil's Uighur comments". France 24. 15 December 2019. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Ames, Nick (13 December 2019). "Arsenal distance themselves from Mesut Özil comments on Uighurs' plight". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- Aaro, David (15 December 2019). "Soccer star Mesut Özil criticizes Muslim detention camp, spurs Chinese TV to pull match". Fox News Channel. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- "Mesut Ozil: Arsenal-Manchester City game removed from schedules by China state TV". 15 December 2019. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- Flor, Mamela Fiallo (13 April 2020). "WHO's Chinese Loyalties: Ignores Taiwan's Success Against Coronavirus". PanAm Post. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "EU defends censorship of letter in Chinese newspaper | DW | 07.05.2020". Deutsche Welle. 7 May 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Taylor, Max Roger (26 May 2020). "China-EU relations: self-censorship by EU diplomats is commonplace". The Conversation. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Vincent, James (26 May 2020). "YouTube is deleting comments with two phrases that insult China's Communist Party". The Verge. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Davison, Helen; Kuo, Lily (12 June 2020). "Zoom admits cutting off activists' accounts in obedience to China". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Watts, Jonathan (13 January 2010). "Google pulls out of China: what the bloggers are saying". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Gallagher, Ryan (1 August 2018). "Google Plans to Launch Censored Search Engine in China, Leaked Documents Reveal". The Intercept. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- "Google's Chinese search engine 'terminated'". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 17 July 2019. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Brito, Christopher (8 October 2019). ""South Park" creators offer fake apology to China after reported ban". CBS News. CBS. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Bradley, Laura (10 October 2019). "South Park Isn't Done Needling the Chinese government". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Chu, Karen (9 October 2019). "Notorious 'South Park' China Episode Screened on the Streets of Hong Kong". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Beach, Sophie (11 October 2019). "Foreign Companies and the Internalization of Chinese Propaganda". China Digital Times. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.