Qamishli

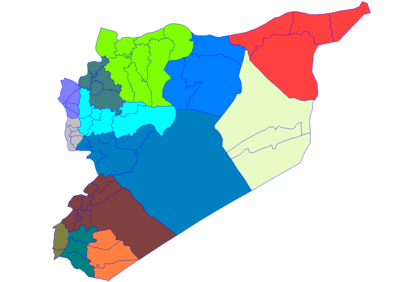

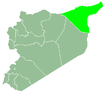

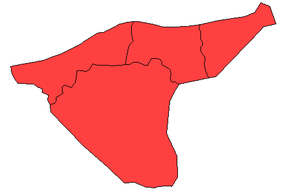

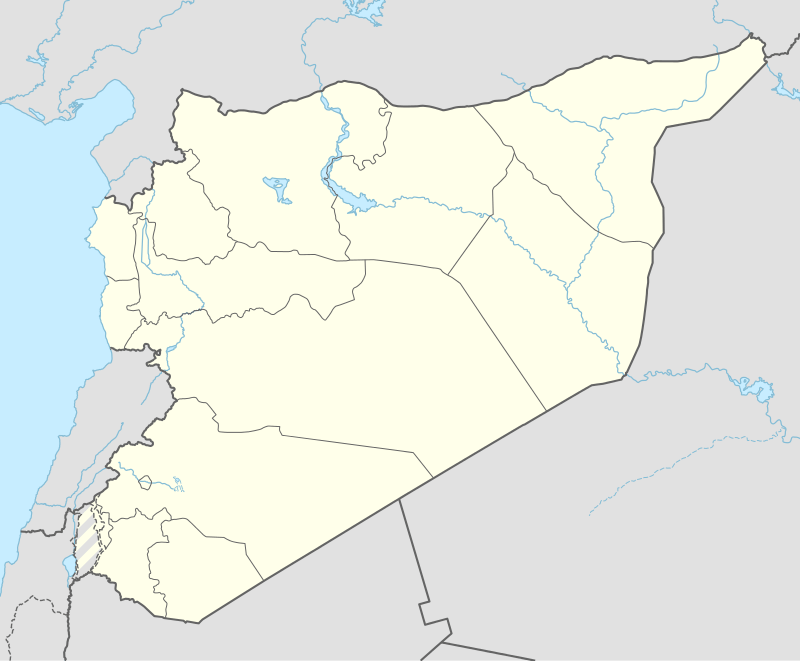

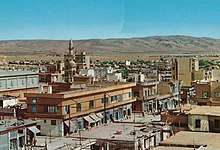

Qamishli (Arabic: القامشلي,[2] Kurdish: Qamişlo ,قامشلۆ[3][4]) is a city in northeastern Syria on the Syria–Turkey border, adjoining the city of Nusaybin in Turkey. According to the 2004 census, Qamishli had a population of 184,231.[1] Qamishli is 680 kilometres (420 mi) northeast of Damascus.[5]

Qamishli Arabic: القامشلي Kurdish: Qamişlo ,قامشلۆ | |

|---|---|

| |

Qamishli Location of Qamishli in Syria | |

| Coordinates: 37°03′N 41°13′E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | al-Hasakah |

| District | Qamishli |

| Subdistrict | Qamishli |

| Established | 1926 |

| Elevation | 455 m (1,493 ft) |

| Population (2004)[1] | 184,231 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Area code | +963 52 |

| Geocode | C4564 |

| Website | http://www.kamishli.com |

The city is the administrative capital of the Qamishli District of Al-Hasakah Governorate, and the administrative center of Qamishli Subdistrict, consisting of 92 localities with a combined population of 232,095 in 2004. In the course of the Syrian Civil War, Qamishli became the capital of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria.[6]

Etymology

The city was initially a small village inhabited by Assyrians called Syriac: ܒܝܬ ܙܠܝ̈ܢ, romanized: Bēṯ Zālīn meaning House of Reeds[7]. The current name is a Turkified form of this, as "Kamış" means "reed" in Turkish (the Turkish name for the city is Kamışlı).

Demographics

With a population of 184,231 (2004 Census), Qamishli is among the 10 largest cities in Syria by population.

Qamishli is an ethnically mixed city, inhabited predominantly by Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians,[lower-alpha 1] and Armenians, with Assyrians and Armenians making up a significant minority. The city is considered to be a Christian center in Syria. It was founded by Assyrian refugees fleeing the Assyrian genocide in Anatolia.[8][9]

Before the Syrian Civil War, the Christian population of Qamishli was about 40,000, of whom 25,000 belonged to the Syriac Orthodox Church, the biggest church in the city. As of 2014 it was believed that half of all Christians had left the city.[10]

Historically, Qamishli was also home to a significant Jewish community. The origin of the Jews of Qamishli (unlike the Jews of Damascus and Aleppo who are a mixture of Sephardi Jews and Musta'arabi Jews) is the adjoining city of Nusaybin, on the other side of the Turkish-Syrian border. In the 1930s the Jewish population of Qamishli numbered 3,000. After the escalation of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in 1947, the situation of the Jews of Qamishli deteriorated. The exodus of Jews from Syria peaked due to violence, such as the 1947 anti-Jewish riots in Aleppo. By 1963, the community had dwindled to 800, and after the Six-Day War it went down further to 150, of whom only few remain today.

History

The city was officially founded as Qamishli in 1926 as a railway station on the Taurus railway.[11]

Qamishli, the second largest city in al-Hasakah Governorate, is considered a center for both the Kurdish and the Assyrian ethnic groups in Syria. It was heavily settled by refugees from the Assyrian genocide. Assyrians were the majority in the city until the 1970s, when Kurds from the surrounding countryside moved into the city in numbers. Qamishli is renowned for its large Christmas parade and Newroz and Kha b-Nisan festivals.

21st century

In March 2004, during a chaotic soccer match, the Qamishli riots began when visiting Arab fans from Deir ez-Zor started praising Saddam Hussein to taunt the Kurdish home fans. The riot expanded out of the stadium and weapons were used against people of Kurdish background. In the aftermath, at least 30 Kurds were killed as the Syrian security services took over the city.[12] The event became known the "Qamishli massacre".

In June 2005, thousands of Kurds demonstrated in Qamishli to protest the assassination of Sheikh Khaznawi, a Kurdish cleric in Syria, resulting in the death of one policeman and injury to four Kurdish civilians.[13][14] In March 2008, according to Human Rights Watch,[15] three more Kurds were killed when Syrian security forces opened fire on people celebrating the spring festival of Newroz.

Syrian Civil War

With the Syrian Civil War and the Rojava conflict from 2011, the city grew into a major political role, being the de facto capital of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, a self declared autonomous region in northern Syria.

In October 2015, the city's airport, the Qamishli Airport was briefly closed,[16] before reopening again. Syrian airline companies including Cham Wings Airlines, FlyDamas and Syrian Air all provide regular flights into Qamishli from Damascus, Latakia and Beirut. The airport also receives seasonal foreign flights from Germany and Switzerland.[17]

On 27 July 2016, 44 people were killed and many injured after twin blasts attack rocked the city. The Islamic State claimed responsibility for the attack.[18]

Government

The Syrian government remains in control of the airport, the border crossing, and various government buildings such as hospitals, many residential neighborhoods, and various mosques and churches. The government also manages the salaries of its employees, the production and the distribution of the harvest in the countryside, and organizes flights into and from the city to other various Syrian cities and Beirut. Most of the city is under the administration of the de facto Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria,[19] whereby the city serves as the capital of Jazira Canton as well as the capital of the federation as a whole.

While the situation has proved stable over the years, there have been occasional instances of armed conflict between pro-government forces and Sootoro against the Asayish, the most notable being the April 2016 Qamishli clashes, which lasted for two days before ending in a ceasefire and the recapture of the city's central prison by the Kurdish forces.

Also, many bombings have occurred in the city throughout the war, with ISIL claiming responsibility for many of the attacks, most notably on July 2016 where a double blast killed over 40 people and injured more. Qamishli is home to Chirkin prison, which houses detained Islamic State militants.[20]

Climate

The Köppen climate classification subtype for this climate is "Csa" (Mediterranean climate; dry-summer subtropical climate). The summers tend to be dry and warm, with July being the hottest month of the year, while the winters are usually cold and wet, with January being the coldest month with also an average of 11 days of rain. In total, around 53 days of rain occur every year.[21]

| Climate data for Qamishli (1961–1990, extremes 1952–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.6 (74.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

36.4 (97.5) |

41.0 (105.8) |

46.0 (114.8) |

48.5 (119.3) |

47.3 (117.1) |

44.0 (111.2) |

38.6 (101.5) |

29.8 (85.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

48.5 (119.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

29.1 (84.4) |

36.0 (96.8) |

40.3 (104.5) |

39.5 (103.1) |

35.3 (95.5) |

27.7 (81.9) |

19.5 (67.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.2 (90.0) |

31.5 (88.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.0 (46.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.2 (50.4) |

14.7 (58.5) |

19.6 (67.3) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

8.8 (47.8) |

4.1 (39.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.3 (11.7) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

4.6 (40.3) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−11.3 (11.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 78.3 (3.08) |

70.5 (2.78) |

65.0 (2.56) |

66.3 (2.61) |

29.5 (1.16) |

1.7 (0.07) |

0.2 (0.01) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.01) |

21.7 (0.85) |

37.1 (1.46) |

68.4 (2.69) |

439.0 (17.28) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.6 | 7.9 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 3.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 3.2 | 4.9 | 7.9 | 53.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 68 | 64 | 60 | 47 | 29 | 24 | 24 | 27 | 39 | 57 | 70 | 48 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 148.8 | 154.0 | 204.6 | 222.0 | 288.3 | 339.0 | 356.5 | 350.3 | 312.0 | 254.2 | 192.0 | 148.8 | 2,970.5 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 4.8 | 5.5 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 9.3 | 11.3 | 11.5 | 11.3 | 10.4 | 8.2 | 6.4 | 4.8 | 8.1 |

| Source 1: NOAA[22] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (humidity, 1974–1978),[23] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[24] | |||||||||||||

Transportation

Qamishli Airport was closed to civilians in October 2015, but later reopened. Syrian flight companies including Cham Wings Airlines, FlyDamas and Syrian Air provide flights into Qamishli from Damascus, Latakia and Beirut.

Economy

The Al-Hasakah Governorate is not only Syria's most famed grain-producing governorate, but also the source of nearly half of Syria's extracted oil.[25] In December 2017, in preparation for the winter grain season, the government signed deals with the farming corporation in al-Hasakah and many local farmers to receive the wheat and barley planted across 58,000 acres in al-Hasakah, and to plant more in preparation for next year.[26]

Media and education

The Kurdish-language newspaper Nu Dem has its headquarters in Qamishli.[5]

While prior to the Rojava conflict, there had been no institution of higher education in northeastern Syria, in September 2014 the Mesopotamian Social Sciences Academy started teaching.[6][27] Following the University of Afrin,[28] in July 2016 the Jazira Canton's Board of Education officially established the second Syrian Kurdish university in Qamishli. The University of Rojava initially comprised four faculties: Medicine, Engineering, Sciences, and Arts and Humanities. Programs taught include health, oil, computer and agricultural engineering, physics, chemistry, history, psychology, geography, mathematics, primary school teaching, and Kurdish literature.[29][30]

Notable people

- Aram Tigran, singer

- Ciwan Haco, singer

- Gregorius Yohanna Ibrahim, Syriac Orthodox Archbishop of Aleppo

See also

- Assyrians in Syria

- Kurds in Syria

- 2004 Qamishli riots

- 2015 Qamishli bombings

- Qamishli clashes (April 2016)

- Armenian Catholic Eparchy of Qamishli

- Mor Bosous Monastery in Hedil

Notes

- See also the article Terms for Syriac Christians

References

- "2004 Census Data for Nahiya Qamishli" (in Arabic). Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics. Also available in English: UN OCHA. "2004 Census Data". Humanitarian Data Exchange.

- Welle, Deutsche. "سوريا: قتلى وجرحى في ثلاثة انفجارات تهز مدينة القامشلي". DW.COM (in Arabic). Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- "Şaredariya Qamişlo bajar paqij dike" (in Kurdish). Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- "بەکاتی قامشلۆ 10/12/2019". Rûdaw (in Kurdish). Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- Zurutuza, Carlos. "Syria's first Kurdish-language newspaper." (Archive) Al Jazeera. 18 October 2013. Retrieved on 22 October 2013.

- "A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS' Backyard". New York Times. 2015-11-29. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- Thomas A. Carlson et al., “Qamishli — ܒܝܬ ܙ̈ܠܐ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modified January 14, 2014, http://syriaca.org/place/160.

- (in Armenian) Ծննդավայրս՝ Գամիշլի կամ Եղէգնուտ Archived 2012-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- "al-Qamishli – Syria". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung GmbH (24 November 2014). "Islamischer Staat: Die Kirche der Jungfrau in Qamischli". FAZ.NET. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Al-Qāmishlī | Syria". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- James Brandon (February 15, 2007). "The PKK and Syria's Kurds". Terrorism Monitor. Washington, DC: The Jamestown Foundation. p. Volume 5, Issue 3. Archived from the original on November 7, 2007.

- Blanford, Nicholas (June 15, 2005). "A murder stirs Kurds in Syria". USA Today.

- Fattah, Hassan M. (July 2, 2005). "Kurds, Emboldened by Lebanon, Rise Up in Tense Syria". The New York Times.

- "Syria: Investigate Killing of Kurds". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Hasakah's Qamishli International Airport now closed to civilians". SYRIA:direct. 21 October 2015.

- Qamishli - Cham Wings

- "At least 44 dead in ISIS-claimed double bomb attack in Qamishli, Syria". RT. July 27, 2016.

- "'We have nothing': Syrian Kurds risk their lives crossing into Turkey". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Perry, Tom (October 10, 2019). Kasolowsky, Raissa (ed.). "Turkey shelled prison holding IS foreign fighters Kurdish-led administration". Reuters.

- "Qamishli, Syria Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Kamishli Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- "Klimatafel von Kamishly / Syrien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- "Station Kamishli" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- Al Monitor, Syria's Oil Crisis, 2013, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/ru/originals/2013/02/syria-oil-crisis.html#

- التعاقد لاستلام إنتاج 58 ألف دونم من القمح والشعير في الحسكة (In Arabic)

- "First New University To Open In Rojava". Rojava Report. 31 August 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- Sardar Mlla Drwish (18 May 2016). "Syria's first Kurdish university attracts controversy as well as students". Al Monitor. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- "'University of Rojava' to be opened". ANF. 2016-07-04. Archived from the original on 2017-01-04. Retrieved 2016-07-04.

- "Kurds establish university in Rojava amid Syrian instability". Kurdistan24. 2016-07-07. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Qamishli. |

- "From Qamishli to Qamishlo: A Trip to Rojava’s New Capital ", Fabrice Balanche, The Washington Institute, 13 April 2017

- "Amnesty Raises Kurd Issue", on Kurds in Qamishli, 2005