Republics of Russia

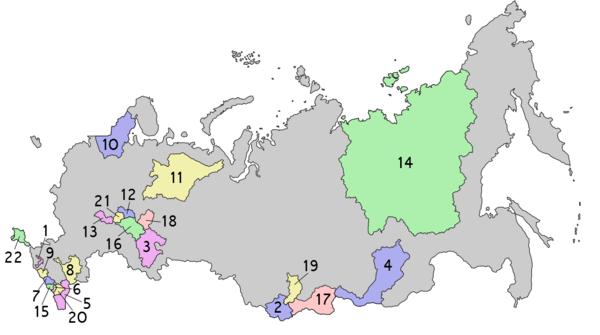

According to its Constitution, Russia is divided into 85 federal subjects (constituent units), 22 of which are "republics". Most of the republics represent areas of non-Russian ethnicity, although there are several republics with Russian majority. The indigenous ethnic group of a republic that gives it its name is referred to as the "titular nationality". Due to decades (in some cases centuries) of internal migration inside Russia, each nationality is not necessarily a majority of a republic's population.

| Republics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Category | Federated state | ||

| Location | Russian Federation | ||

| Number | 22 | ||

| Populations | 206,195 (Altai) – 4,072,102 (Bashkortostan) | ||

| Areas | 3,628 km2 (1,401 sq mi) (Ingushetia) – 3,083,523 km2 (1,190,555 sq mi) (Yakutia) | ||

| Government | Republic Government | ||

| Subdivisions | administrative: districts, cities and towns of republic significance, towns of district significance, urban-type settlements of district significance, selsoviets; municipal: urban okrugs, municipal districts, urban settlements, rural settlements | ||

History

The republics were established in early Soviet Russia. On 15 November 1917, Vladimir Lenin issued the Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia, giving Russia's minorities the right to self-determination.[1] This declaration, however, was never truly meant to grant minorities the right to independence and was only used to garner support among minority groups for the fledgling Soviet state in the ensuing Russian Civil War.[2] When the Soviet Union was formally created on 30 December 1922, the minorities of the country were relegated to Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republics (ASSR), which had less power than the union republics. During the civil war and in its aftermath the Bolsheviks began a process of delimitation in order to draw the borders of the country. Through Joseph Stalin's theory on nationality, borders were drawn to create national homelands for various recognized ethnic groups.[3] Early republics like the Kazakh ASSR and the Turkestan ASSR in Central Asia were dissolved and split up to create new union republics.[4] With delimitation came the policy of korenizatsiya which encouraged the de-Russification of the country and promotion of minority languages and culture.[5] This policy also affected ethnic Russians and was particularly enforced in ASSRs where indigenous people were already a minority in their own homeland, like the Buryat ASSR.[6] Language and culture flourished and ultimately institutionalized ethnicity in the state apparatus of the country.[7] Despite this, the Bolsheviks worked to isolate the country's new republics by surrounding them within Russian territory for fear of them seeking independence. In 1925 the Bashkir ASSR lost its border with the future Kazakh SSR with the creation of the so-called "Orenburg corridor".[8] The Komi-Zyryan Autonomous Oblast lost access to the Barents Sea and became an enclave on 15 July 1929 prior to being upgraded to the Komi ASSR in 1936.[9]

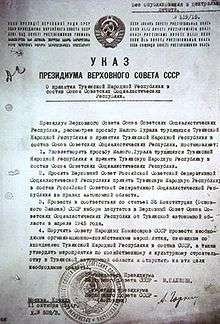

By the 1930s, however, the mood shifted as the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin stopped enforcing korenizatsiya and began purging non-Russians from government and intelligentsia. Thus, a period of Russification set in.[5] Russian became mandatory in all areas of non-Russian ethnicity and the Cyrillic script became compulsory for all languages of the Soviet Union.[10] The constitution stated that the ASSRs had power to enforce their own policies within their territory,[11] but in practice the ASSRs and their titular nationalities were some of the most affected by Stalin's purges and were strictly controlled by Moscow.[12] From 1937, the "bourgeois nationalists" became the "enemy of the Russian people" and korenizatsiya was abolished.[10] On 22 June 1941 Germany invaded the Soviet Union, forcing it in to the Second World War, and advanced deep in to Russian territory. In response, Stalin abolished the Volga German ASSR on 7 September 1941 and exiled the Volga Germans to Central Asia and Siberia.[13] When the Soviets gained the upper hand and began recapturing territory in 1943, many minorities of the country began to be seen as German collaborators by Stalin and were accused of treason, particularly in southern Russia.[14] Between 1943 and 1945 ethnic Balkars,[15] Chechens,[16] Crimean Tatars,[17] Ingush,[16] and Kalmyks[18] were deported en masse from the region to remote parts of the country. Immediately after the deportations the Soviet government passed decrees that liquidated the Kalmyk ASSR on 27 December 1943,[18] the Crimean ASSR on 23 February 1944,[19] the Checheno-Ingush ASSR on 7 March 1944,[16] and renamed the Kabardino-Balkar ASSR the Kabardian ASSR on 8 April 1944.[20] After Stalin's death on 5 March 1953 the new government of Nikita Khrushchev sought to undo his controversial legacy. During his Secret speech on 25 February 1956 Khrushchev rehabilitated Russia's minorities.[21] The Kabardino-Balkar ASSR[22] and the Checheno-Ingush ASSR[23] were restored on 9 January 1957 while the Kalmyk ASSR was restored on 29 July 1958.[23] The government, however, refused to restore the Volga German ASSR[24] and the Crimean ASSR, the latter of which was transferred to the Ukrainian SSR on 19 February 1954.[19]

The autonomies of the ASSRs varied greatly throughout the history of the Soviet Union but Russification would nevertheless continue unabated and internal Russian migration to the ASSRs would result in various indigenous people becoming minorities in their own republics. At the same time, the number of ASSRs grew; the Karelian ASSR was formed on 6 July 1956 after being a union republic from 1940[25] while the partially recognized state of Tuva was annexed by the Soviets on 11 October 1944 and became the Tuvan ASSR on 10 October 1961.[26] By the 1980s General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev's introduction of glasnost began a period of revitalization of minority culture in the ASSRs.[27] From 1989 Gorbachev's Soviet Union and the Russian SFSR, led by Boris Yeltsin, were locked in a power struggle. Yeltsin sought support from the ASSRs by promising more devolved powers and to build a federation "from the ground up".[28] On 12 June 1990 the Russian SFSR issued a Declaration of State Sovereignty, proclaiming Russia a sovereign state whose laws take priority over Soviet ones.[29] The following month Yeltsin told the ASSRs to "take as much sovereignty as you can swallow" during a speech in Kazan, Tatar ASSR.[30] These events prompted the ASSRs to assert themselves against a now weakened Soviet Union. From 20 July 1990 to 2 July 1991 each of the ASSRs followed Russia's lead and issued "declarations of sovereignty", elevating their statuses to that of union republics within a federal Russia.[31]

The Soviet Union collapsed on 26 December 1991 and the position of the ASSRs became uncertain. By law, the ASSRs did not have the right to secede from the Soviet Union like the union republics did[32][33] but the question of independence from Russia nevertheless became a topic of discussion in some of the ASSRs. Yeltsin was an avid supporter of national sovereignty and recognized the independence of the union republics in what was called a "parade of sovereignties".[32] In regards to the ASSRs, however, Yeltsin did not support secession and tried to prevent them from declaring independence. The Checheno-Ingush ASSR, led by Dzhokhar Dudayev, unilaterally declared independence on 1 November 1991[34] and Yeltsin would attempt to retake it on 11 December 1994, beginning the First Chechen War.[35] When the Tatar ASSR held a referendum on whether to declare independence on 21 March 1992, he had the ballot declared illegal by the Constitutional Court.[36]

On 31 March 1992, every subject of Russia except the Tatar ASSR and the de facto state of Chechnya signed the Treaty of Federation with the government of Russia, solidifying its federal structure and Boris Yeltsin became the country's first president.[37] The ASSRs were dissolved and became the modern day republics. The number of republics increased dramatically as former autonomous oblasts were elevated to full republics, including Altai and Karachay-Cherkessia,[38] while the Ingush portion of the Checheno-Ingush ASSR refused to be part of the breakaway state and rejoined Russia as the Republic of Ingushetia on 4 June 1992.[39] The Republic of Tatarstan demanded its own agreement to preserve its autonomy within the Russian Federation and on 15 February 1994, Moscow and Kazan signed a power-sharing deal, in which the latter was granted a high degree of autonomy.[40] 45 other regions, including the other republics, would go on to sign autonomy agreements with the federal center.[41] Toward the end of the 1990s, the overly complex structure of the various bilateral agreements between regional governments and Moscow sparked a call for reform.[42] The constitution of Russia was the supreme law of the country, but in practice, the power-sharing agreements superseded it while the poor oversight of regional affairs left the republics to be governed by authoritarian leaders who ruled for personal benefit.[43] Meanwhile the war in Chechnya entered a stalemate as Russian forces were unable to wrest control of the republic despite capturing the capital Grozny on 8 February 1995 and killing Dudayev months later in an airstrike.[44] Faced with a demoralized army and universal public opposition to the war, Yeltsin was forced to sign the Khasavyurt Accord with Chechnya on 30 August 1996 and eventually withdrew troops.[45] A year later Chechnya and Russia signed the Moscow Peace Treaty, ending Russia's attempts to retake the republic.[46] As the decade drew to a close, the fallout from the failed Chechen war and the subsequent financial crisis in 1998 resulted in Yeltsin resigning on 31 December 1999.[47]

Yeltsin declared Vladimir Putin as interim president and his successor. Despite maintaining de facto independence following the war, Chechnya under Aslan Maskhadov proved incapable of fixing the republic's devastated economy and maintaining order as the territory became increasingly lawless and a breeding ground for Islamic fundamentalism.[48] Using this lawlessness extremists invaded neighboring Dagestan and bombed various apartment blocks in Russia, resulted in Putin sending troops into Chechnya again on 1 October 1999.[49] Chechen resistance quickly fell apart as federal troops captured Grozny on 6 February 2000 and pushed rebels in to the mountains.[50] Moscow reimposed direct rule on Chechnya on 9 June 2000[51] and the territory was officially reintegrated in to the Russian Federation as the Chechen Republic on 24 March 2003.[52] Putin would participate in the 26 March 2000 election on the promise of completely restructuring the federal system and restoring the authority of the central government.[53] The power-sharing agreements began to gradually expire or be voluntarily abolished and after 2003, only Tatarstan and Bashkortostan continued to negotiate on their treaties' extensions.[54] Bashkortostan's power-sharing treaty expired on 7 July 2005,[55] leaving Tatarstan as the sole republic to maintain its autonomy, which was renewed on 11 July 2007.[56] After an attack by Chechen separatists at a school in Beslan, North Ossetia, Putin abolished direct elections for governors and assumed the power to personally appoint and dismiss them.[57] Throughout the decade, influential regional leaders like Mintimer Shaimiev of Tatarstan[58] and Murtaza Rakhimov of Bashkortostan,[59] who were adamant on extending their bilateral agreements with Moscow, were dismissed, removing the last vestiges of regional autonomy from the 1990s. On 24 July 2017, Tatarstan's power-sharing agreement with Moscow expired, making it the last republic to lose its special status. After the agreement's termination, some commentators expressed the view that Russia ceased to be a federation.[60][61][40]

Constitutional status

Republics differ from other federal subjects in that they have the right to establish their own official language,[63] have their own constitution, and have a national anthem. Other federal subjects, such as krais and oblasts, are not explicitly given this right. During Boris Yeltsin's presidency, the republics were the first subjects to be granted extensive power from the federal government, and were often given preferential treatment over other subjects, which has led to Russia being characterized as an "asymmetrical federation ".[64][65] The Treaty of Federation signed on 31 March 1992 stipulated that the republics were "sovereign states" that had expanded rights over natural resources, external trade, and internal budgets.[66] The signing of bilateral treaties with the republics would grant them additional powers, however, the amount of autonomy given differed by republic and was mainly based on their economic wealth rather than ethnic composition.[67] Yakutia, for example, was granted more control over its resources, being able to keep most of its revenue and sell and receive its profits independently due to its vast diamond deposits.[68] North Ossetia on the other hand, a poorer republic, was mainly granted more control over defense and internal security due to its location in the restive North Caucasus.[69] Tatarstan and Bashkortostan had the authority to establish their own foreign relations and conduct agreements with foreign governments.[70] This has led to criticism from oblasts and krais. After the 1993 Russian constitutional crisis, the current constitution was adopted but the republics were no longer classified as "sovereign states" and all subjects of the federation were declared equal, though maintaining the validity of the bilateral agreements.[71]

In theory, the constitution of Russia was the ultimate authority over the republics, but the power-sharing treaties held greater weight in practice. Republics often created their own laws which contradicted the constitution.[70] Yeltsin, however, made little effort to rein in renegade laws, preferring to turn a blind eye to violations in exchange for political loyalty.[72] Vladimir Putin's election on 26 March 2000 began a period of extensive reforms to centralize authority with the federal government and bring all laws in line with the constitution.[73] His first act as president was the creation of federal districts on 18 May 2000, which were tasked with exerting federal control over the country's subjects.[74] Putin later established the so-called "Kozak Commission" in June 2001 to examine the division of powers between the government and regions.[75] The Commission's recommendations focused mainly on minimizing the bases of regional autonomy and transferring lucrative powers meant for the republics to the federal government.[76] Centralization of power would continue as the republics gradually lost more and more autonomy to the federal government, leading the European Parliament to conclude that despite calling itself a federation, Russia functions as a unitary state.[77] On 21 December 2010, the State Duma voted to overturn previous laws allowing the leaders of the republics to hold the title of President[78] while a bill was passed on 19 June 2018 that elevated the status of the Russian language at the expense of other official languages in the republics.[79] The bill authorized the abolishment of mandatory minority language classes in schools and for voluntary teaching to be reduced to two hours a week.[80]

There are secessionist movements in most republics, but these are generally not very strong. The constitution makes no mention on whether a republic can legally secede from the Russian Federation. However, the Constitutional Court of Russia ruled after the unilateral secession of Chechnya in 1991 that the republics do not have the right to secede and are inalienable parts of the country.[81] Despite this, some republican constitutions in the 1990s had articles giving them the right to become independent. This included Tuva, whose constitution had an article explicitly giving it the right to secede.[70] However, following Putin's centralization reforms in the early 2000s, these articles were subsequently dropped. The Kabardino-Balkar Republic, for example, adopted a new constitution in 2001 which prevents the republic from existing independently of the Russian Federation.[82] After Russia's annexation of Crimea, the State Duma adopted a law to penalize people calling for the separation of any part of the country on 5 July 2014.[83]

Status of Crimea

On 18 March 2014, the Autonomous Republic of Crimea of Ukraine was annexed by Russia after a disputed referendum.[84] The peninsula subsequently became the Republic of Crimea, the 22nd republic of Russia. However, Ukraine and most of the international community do not recognize Crimea's annexation[85] and the United Nations General Assembly declared the vote to be illegitimate.[86]

Republics

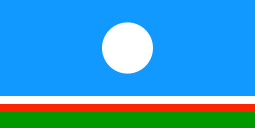

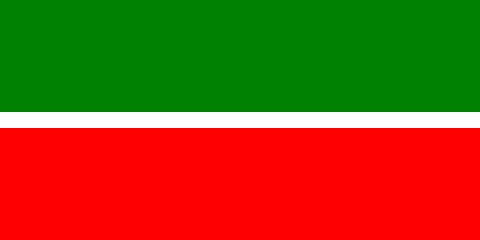

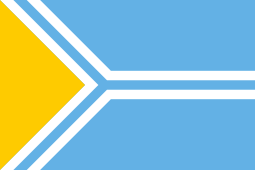

| Flag | Map | Name |

Domestic common and formal names |

Capital |

Titular Nationality |

Population (2010)[87] |

Area |

Formation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) |

Adygea Republic of Adygea |

Russian: Адыгея — Республика Адыгея (Adygeya — Respublika Adygeya) Adyghe: Адыгэ — Адыгэ Республик (Adygæ — Adygæ Respublik) |

Maykop Russian: Майкоп (Maykop) Adyghe: Мыекъуапэ (Myjæqwapæ) |

Adyghe | 439,996 | 7,792 km2 (3,009 sq mi) | 1991-07-03[88] | |

|

Altai Altai Republic |

Russian: Алтай — Республика Алтай (Altay — Respublika Altay) Altay: Алтай — Алтай Республика (Altay — Altay Respublika) |

Gorno-Altaysk Russian: Горно-Алтайск (Gorno-Altaysk) Altay: Туулу Алтай (Tuulu Altay) |

Altai | 206,168 | 92,903 km2 (35,870 sq mi) | 1991-07-03[88] | |

|

Bashkortostan Republic of Bashkortostan |

Russian: Башкортостан — Республика Башкортостан (Bashkortostan — Respublika Bashkortostan) Bashkir: Башҡортостан — Башҡортостан Республикаһы (Bašǩortostan — Bašǩortostan Respublikaḥy) |

Ufa Russian: Уфа (Ufa) Bashkir: Өфө (Öfö) |

Bashkirs | 4,072,292 | 142,947 km2 (55,192 sq mi) | 1919-03-23[89] | |

.svg.png) |

Buryatia Republic of Buryatia |

Russian: Бурятия — Республика Бурятия (Buryatiya — Respublika Buryatiya) Buryat: Буряадия — Буряад Улас (Buryaadiya — Buryaad Ulas) |

Ulan-Ude Russian: Улан-Удэ (Ulan-Ude) Buryat: Улаан Үдэ (Ulaan Üde) |

Buryats | 972,021 | 351,334 km2 (135,651 sq mi) | 1923-05-30[90] | |

.svg.png) |

Chechnya Chechen Republic |

Russian: Чечня — Чеченская Республика (Chechnya — Chechenskaya Respublika) Chechen: Нохчийчоь — Нохчийн Республика (Noxçiyçö — Noxçiyn Respublika) |

Grozny Russian: Грозный (Grozny) Chechen: Соьлжа-ГӀала (Sölƶa-Ġala) |

Chechens | 1,268,989 | 16,165 km2 (6,241 sq mi) | 1993-01-10[lower-alpha 1] | |

|

Chuvashia Chuvash Republic |

Russian: Чувашия — Чувашская Республика (Chuvashiya — Chuvashskaya Respublika) Chuvash: Чӑваш Ен — Чӑваш Республики (Čăvaš Jen — Čăvaš Respubliki) |

Cheboksary Russian: Чебоксары (Cheboksary) Chuvash: Шупашкар (Šupaškar) |

Chuvash | 1,251,619 | 18,343 km2 (7,082 sq mi) | 1925-04-21[91] | |

|

Crimea[lower-alpha 2] Republic of Crimea |

Russian: Крым — Республика Крым (Krym — Respublika Krym) Ukrainian: Крим — Республіка Крим (Krym — Respublika Krym) Crimean Tatar: Къырым — Къырым Джумхуриети (Qırım — Qırım Cumhuriyeti) |

Simferopol Russian: Симферополь (Simferopol) Ukrainian: Сiмферополь (Simferopol) Crimean Tatar: Акъмесджит (Aqmescit) |

—[lower-alpha 3] | 1,913,731 | 26,081 km2 (10,070 sq mi) | 2014-03-18[84] | |

.svg.png) |

Dagestan Republic of Dagestan |

Russian: Дагестан — Республика Дагестан (Dagestan — Respublika Dagestan) | Makhachkala Russian: Махачкала (Makhachkala) |

Nine indigenous nationalities[lower-alpha 4] | 2,910,249 | 50,270 km2 (19,409 sq mi) | 1921-01-20[93] | |

.svg.png) |

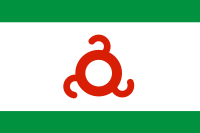

Ingushetia Republic of Ingushetia |

Russian: Ингушетия — Республика Ингушетия (Ingushetiya — Respublika Ingushetiya) Ingush: ГӀалгIайче — ГIалгIай Мохк (Ghalghajche — Ghalghaj Moxk) |

Magas Russian: Магас (Magas) Ingush: Магас (Magas) |

Ingush | 412,529 | 3,628 km2 (1,401 sq mi) | 1992-06-04[39] | |

|

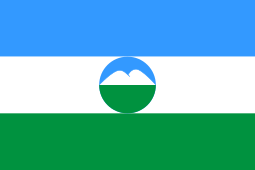

Kabardino-Balkaria Kabardino-Balkar Republic |

Russian: Кабардино-Балкария — Кабардино-Балкарская Республика (Kabardino-Balkariya — Kabardino-Balkarskaya Respublika) Kabardian: Къэбэрдей-Балъкъэрия — Къэбэрдей-Балъкъэр Республикэ (Ķêbêrdej-Baĺķêriya — Ķêbêrdej-Baĺķêr Respublikê) Karachay-Balkar: Къабарты-Малкъария — Къабарты-Малкъар Республика (Qabarti-Malqariya — Qabartı-Malqar Respublika) |

Nalchik Russian: Нальчик (Nalchik) Kabardian: Налщӏэч (Nalshchech) Karachay-Balkar: Нальчик (Nalchik) |

Kabardians, Balkars | 859,939 | 12,470 km2 (4,815 sq mi) | 1936-12-05[94] | |

.svg.png) |

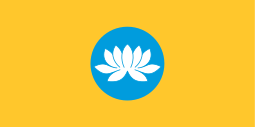

Kalmykia Republic of Kalmykia |

Russian: Калмыкия — Республика Калмыкия (Kalmykiya — Respublika Kalmykiya) Kalmyk: Хальмг — Хальмг Таңһч (Haľmg — Haľmg Tañğç) |

Elista Russian: Элиста (Elista) Kalmyk: Элст (Elst) |

Kalmyks | 289,481 | 74,731 km2 (28,854 sq mi) | 1935-10-22[93] | |

|

Karachay-Cherkessia Karachay-Cherkess Republic |

Russian: Карачаево-Черкесия — Карачаево-Черкесская Республика (Karachayevo-Cherkesiya — Karachayevo-Cherkesskaya Respublika) Karachay-Balkar: Къарачай-Черкесия — Къарачай-Черкес Республика (Qaraçay-Çerkesiya — Qaraçay-Çerkes Respublika) Kabardian: Къэрэшей-Шэрджэсия — Къэрэшей-Шэрджэс Республикэ (Ķêrêšei-Šêrdžêsiya — Ķêrêšei-Šêrdžês Respublikê) |

Cherkessk Russian: Черкесск (Čerkessk) Karachay-Balkar: Черкесск (Çerkessk) Kabardian: Шэрджэс къалэ (Şărdjăs qală) |

Karachays, Kabardians | 477,859 | 14,277 km2 (5,512 sq mi) | 1991-07-03[88] | |

.svg.png) |

Karelia Republic of Karelia |

Russian: Карелия — Республика Карелия (Kareliya — Respublika Kareliya) Karelian: Karjala — Karjalan tazavaldu[lower-alpha 5] |

Petrozavodsk Russian: Петрозаводск (Petrozavodsk) Karelian: Petroskoi |

Karelians | 643,548 | 180,520 km2 (69,699 sq mi) | 1923-06-27 | |

|

Khakassia Republic of Khakassia |

Russian: Хакасия — Республика Хакасия (Khakasiya — Respublika Khakasiya) Khakas: Хакасия — Хакас Республиказы (Khakasiya — Khakas Respublikazy) |

Abakan Russian: Абакан (Abakan) Khakas: Абахан (Abakhan) |

Khakas | 532,403 | 61,569 km2 (23,772 sq mi) | 1991-07-03[88] | |

.svg.png) |

Komi Komi Republic |

Russian: Коми — Республика Коми (Komi — Respublika Komi) Komi: Коми — Коми Республика (Komi — Komi Respublika) |

Syktyvkar Russian: Сыктывкар (Syktyvkar) Komi: Сыктывкар (Syktyvkar) |

Komi | 901,189 | 416,774 km2 (160,917 sq mi) | 1936-12-05[93] | |

|

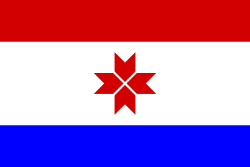

Mari El Mari El Republic |

Russian: Марий Эл — Республика Марий Эл (Mariy El — Respublika Mariy El) Hill Mari: Мары Эл — Мары Эл Республик (Mary El — Mary El Republik) Meadow Mari: Марий Эл — Марий Эл Республик (Mariy El — Mariy El Republik) |

Yoshkar-Ola Russian: Йошкар-Ола (Yoshkar-Ola) Hill Mari: Йошкар-Ола (Yoshkar-Ola) Meadow Mari: Йошкар-Ола (Yoshkar-Ola) |

Mari | 696,459 | 23,375 km2 (9,025 sq mi) | 1936-12-05[93] | |

|

Mordovia Republic of Mordovia |

Russian: Мордовия — Республика Мордовия (Mordoviya — Respublika Mordoviya) Moksha: Мордовия — Мордовия Pеспубликсь (Mordovija — Mordovija Respublikas) Erzya: Мордовия — Мордовия Республикась (Mordovija — Mordovija Respublikas) |

Saransk Russian: Саранск (Saransk) Moksha: Саранош (Saranosh) Erzya: Саран ош (Saran osh) |

Mordvins | 834,755 | 26,128 km2 (10,088 sq mi) | 1934-12-20[96] | |

|

.svg.png) |

North Ossetia–Alania Republic of North Ossetia–Alania |

Russian: Северная Осетия–Алания — Республика Северная Осетия–Алания (Severnaya Osetiya–Alaniya — Respublika Severnaya Osetiya–Alaniya) Ossetian: Цӕгат Ирыстон–Алани — Республикӕ Цӕгат Ирыстон–Алани (Cægat Iryston–Alani — Respublikæ Cægat Iryston–Alani) |

Vladikavkaz Russian: Владикавказ (Vladikavkaz) Ossetian: Дзæуджыхъæу (Dzæudžyqæu) |

Ossetians | 712,980 | 7,987 km2 (3,084 sq mi) | 1936-12-05[94] |

_(Crimea_disputed).svg.png) |

Yakutia Sakha Republic |

Russian: Якутия — Республика Саха (Yakutiya — Respublika Sakha) Yakut: Caxa Сирэ — Саха Өрөспүүбүлүкэтэ (Sakha Sire — Sakha Öröspüübülükete) |

Yakutsk Russian: Якутск (Yakutsk) Yakut: Дьокуускай (Dokuuskay) |

Yakuts | 958,528 | 3,083,523 km2 (1,190,555 sq mi) | 1922-04-27 | |

|

Tatarstan Republic of Tatarstan |

Russian: Татарстан — Республика Татарстан (Tatarstan — Respublika Tatarstan) Tatar: Татарстан — Татарстан Республикасы (Tatarstan — Tatarstan Respublikası) |

Kazan Russian: Казань (Kazan) Tatar: Казан (Kazan) |

Tatars | 3,786,488 | 67,847 km2 (26,196 sq mi) | 1920-06-25[89] | |

|

Tuva Tuva Republic |

Russian: Тува — Республика Тyва (Tuva — Respublika Tuva) Tuvan: Тыва — Тыва Республика (Tyva — Tyva Respublika) |

Kyzyl Russian: Кызыл (Kyzyl) Tuvan: Кызыл (Kızıl) |

Tuvans | 307,930 | 168,604 km2 (65,098 sq mi) | 1961-10-10[26] | |

|

Udmurtia Udmurt Republic |

Russian: Удмуртия — Удмурт Республика (Udmurtiya — Respublika Udmurt) Udmurt: Удмуртия — Удмурт Элькун (Udmurtiya — Udmurt Elkun) |

Izhevsk Russian: Ижевск (Izhevsk) Udmurt: Ижкар (Ižkar) |

Udmurts | 1,521,420 | 42,061 km2 (16,240 sq mi) | 1934-12-28 |

- De facto independent state from 1991 to 2000 but was still recognized as a Russian republic.

- Annexed by Russia in 2014; recognized as a part of Ukraine by most of the international community.

- The republic was not formed with a titular nationality in mind.[92]

- Aghuls, Avars, Dargins, Kumyks, Laks, Lezgins, Rutuls, Tabasarans, Tsakhurs.

- The Karelian language has no official status in the republic but is nevertheless recognized as a "regional language" alongside Finnish and Veps.[95]

Demographics trend

| Ethnic group | Titular (%) | Russians (%) | other (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republic | 1979 | 1989 | 2002 | 2010[87] | 1979 | 1989 | 2002 | 2010 | 1979 | 1989 | 2002 | 2010 |

| Adygea | 21,3 | 70,8 | ||||||||||

| Altai | 5,6 | |||||||||||

| Bashkortostan | 24,3 | 40,3 | 24,5 | |||||||||

| Buryatia | ||||||||||||

| Chechnya | 52,9 | 31,7 | ||||||||||

| Chuvashia | ||||||||||||

| Dagestan | 86,0 | 11,0 | ||||||||||

| Ingushetia | ||||||||||||

| Kabardino-Balkaria | 45,6 | 35,1 | 9,0 | |||||||||

| Kalmykia | ||||||||||||

| Karachay-Cherkessia | 29,7 | 45,0 | 9,3 | |||||||||

| Karelia | ||||||||||||

| Komi | ||||||||||||

| Khakassia | ||||||||||||

| Mari El | ||||||||||||

| Mordovia | ||||||||||||

| North Ossetia–Alania | ||||||||||||

| Yakutia | ||||||||||||

| Tatarstan | ||||||||||||

| Tuva | ||||||||||||

| Udmurtia | ||||||||||||

Attempted republics

In response to the apparent federal inequality, in which the republics were given special privileges during the early years of Yeltsin's tenure at the expense of other subjects, Eduard Rossel, then governor of Sverdlovsk Oblast and advocate of equal rights for all subjects, attempted to transform his oblast into the Ural Republic on 1 July 1993 in order to receive the same benefits.[97] Initially supportive, Yeltsin later dissolved the republic and fired Rossel on 9 November 1993.[98] The only other attempt to formally create a republic occurred in Vologda Oblast when authorities declared their wish to create a "Vologda Republic" on 14 May 1993. This declaration, however, was ignored by Moscow and eventually faded from public consciousness.[99] Other attempts to unilaterally create a republic never materialized. These included a "Pomor Republic" in Arkhangelsk Oblast,[99] a "Southern Urals Republic" in Chelyabinsk Oblast,[100] a "Chukotka Republic" in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug,[101] a "Yenisei Republic" in Irkutsk Oblast,[100] a "Leningrad Republic" in Leningrad Oblast,[99] a "Nenets Republic" in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug,[102] a "Siberian Republic" in Novosibirsk Oblast,[99] a "Primorsky Republic" in Primorsky Krai,[100] a "Neva Republic" in the city of Saint Petersburg,[100] and a republic consisting of eleven regions in western Russia centered around Oryol Oblast.[99]

Other attempts to create republics came in the form of splitting up already existing territories. After the Soviet Union's collapse, a proposal was put forth to split the Karachay-Cherkess Republic in to multiple smaller republics. The idea was rejected by referendum on 28 March 1992.[103] A similar proposal occurred in the Republic of Mordovia to divide it to separate Erzyan and Mokshan homelands. The proposal was rejected in 1995.[104]

Entities outside Russia

See also

References

- Bashqawi, Adel (2017). Circassia: Born to Be Free. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-5434-4765-1.

It also issued the Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia on 15 November 1917, in which the equality of all peoples was proclaimed, and in which the 'right of self-determination, even unto separation' was formally recognized.

- Mälksoo, Lauri (April 2017). "Soviet Approach to Right of Peoples to Self-Determination". History of International Law 2017: 7–8 – via ResearchGate.

- Ness, Immanuel; Cope, Zak (2016). The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillian. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-230-39278-6.

- Feldbrugge, Ferdinand; Van den Berg, Gerard; Simons, William (1985). Encyclopedia of Soviet Law. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 467. ISBN 90-247-3075-9.

- Greenacre, Liam (August 23, 2016). "Korenizatsiya: The Soviet Nationalities Policy for Recognised Minorities". Liam's Look at History. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Bazarova V. V. On the problems of indigenization in the national autonomies of Eastern Siberia in the 1920s - 1930s. // Power. - 2013. - № 12. - p. 176.

- Kemp, Walter (1999). Nationalism and Communism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union: A Basic Contradiction?. Basingstoke: Macmillian Press LTD. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-230-37525-3.

- Pavlo, Podobed (March 28, 2019). "Idel-Ural: Polyethnic Volcano of the Russian Federation". Prometheus Security Environment Research Center. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- "Komi and imperial policy in the Arctic". Free Idel-Ural. June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Timo Vihavainen: Nationalism and Internationalism. How did the Bolsheviks Cope with National Sentiments? in Chulos & Piirainen 2000, p. 85.

- Rett, Ludwikowski (1996). Constitution-making in the Region of Former Soviet Dominance. London and Durham: Duke University Press. p. 618. ISBN 978-0-8223-1802-6.

- "Ethnic and Religious Minorities in Stalin's Soviet Union" (PDF). Ethnic and Religious Minorities: 16. 2017.

The cultural and linguistic factors and the isolation of minority communities from the rest of the population thus required additional surveillance of ethnic as well as religious groups by the secret service.

- "Punished Peoples" of the Soviet Union: The Continuing Legacy of Stalin's Deportations" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. September 1991. pp. 11–12. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Alexander Statiev, "The Nature of Anti-Soviet Armed Resistance, 1942–44", Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History (Spring 2005) 285–318

- Bugay, Nikolay (1996). The Deportation of Peoples in the Soviet Union. New York: Nova Science Publishers. p. 156. ISBN 1-56072-371-8.

- Askerov, Ali (2015). Historical Dictionary of the Chechen Conflict. New York: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4422-4925-7.

- Pohl, Otto (2000). "The Deportation and Fate of the Crimean Tatars" (PDF). Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Guchinova, Elza-Bair (2007). Deportation of the Kalmyks (1943–1956): Stigmatized Ethnicity. Sapporo: Hokkaido University. pp. 187–188.

- "Transfer of the Crimea to the Ukraine". International Committee for Crimea. July 2005. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- "Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of April 8, 1944 "On the resettlement of Balkars living in the Kabardino-Balkarian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, and on the renaming of the Kabardino-Balkarian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in the Kabardian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic"". Library USSR (in Russian). Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Tanner, Arno (2004). The Forgotten Minorities of Eastern Europe: The History and Today of Selected Ethnic Groups in Five Countries. Helsinki: East-West Books. p. 31. ISBN 9789529168088.

- "Punished Peoples" of the Soviet Union: The Continuing Legacy of Stalin's Deportations" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. September 1991. p. 74. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Polian, Pavel (2004). Against Their Will: The History and Geography of Forced Migrations in the USSR. Budapest: Central European University Press. p. 199. ISBN 963-9241-68-7.

- Minority Rights: Problems, Parameters, and Patterns in the CSCE Context. Washington, DC: Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. 1991. p. 59.

- Gladman, Imogen (2004). The Territories of the Russian Federation 2004. London: Europa Publications. p. 102. ISBN 1-85743-248-7.

- Toomas, Alatalu (1992). "Tuva: A State Reawakens". Soviet Studies. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. 44: 881–895. ISSN 0038-5859. JSTOR 152275.

- Simons, Greg; Westerlund, David (2015). Religion, Politics and Nation-Building in Post-Communist Countries. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. p. 81. ISBN 9781472449696.

- Ross, Cameron (January 1, 2002). Regional Politics in Russia. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 207. ISBN 0-7190-5890-2.

- Woodruff, David (June 12, 1990). "Russian republic declares sovereignty". UPI. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Newton, Julie; Tompson, William (2010). Institutions, Ideas and Leadership in Russian Politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillian. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-349-36232-5.

- Kahn, Jeffery (2002). Federalism, Democratization, and the Rule of Law in Russia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-19-924699-8.

- Yakovlev, Alexander; Berman, Margo (1996). Striving for Law in a Lawless Land: Memoirs of a Russian Reformer. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 104–105. ISBN 1-56324-639-2.

- Saunders, Robert; Strukov, Vlad (2010). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Federation. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. pp. 59. ISBN 978-0-8108-7460-2.

- Higgins, Andrew (January 22, 1995). "Dzhokhar Dudayev: Lone wolf of Grozny". The Independent. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Muratov, Dmitry (December 12, 2014). "'The Chechen wars murdered Russian democracy in its cradle'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Shapiro, Margaret (March 23, 1992). "Tatarstan Votes for Self-Rule Repudiating Russia and Yeltsin". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Smirnova, Lena (July 24, 2017). "Tatarstan, the Last Region to Lose Its Special Status Under Putin". The Moscow Times. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика. Закон №1539-1 от 3 июля 1991 г. «О порядке преобразования Адыгейской, Горно-Алтайской, Карачаево-Черкесской и Хакасской автономных областей в Советские Социалистические Республики в составе РСФСР». (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. Law #1535-1 of July 3, 1991 On the Procedures of the Transformation of Adyghe, Gorno-Altai, Karachay-Cherkess, and Khakass Autonomous Oblasts into the Soviet Socialist Republics of the RSFSR. ).

- Pakhomenko, Varvara (August 16, 2009). "Ingushetia Abandoned". Open Democracy. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- "Russia revoking Tatarstan's autonomy". European Forum for Democracy and Solidarity. August 9, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- Chuman, Mizuki. "The Rise and Fall of Power-Sharing Treaties Between Center and Regions in Post-Soviet Russia" (PDF). Demokratizatsiya: 135.

- Chuman, Mizuki. "The Rise and Fall of Power-Sharing Treaties Between Center and Regions in Post-Soviet Russia" (PDF). Demokratizatsiya: 138.

- "Nations in Transit: Russia". Freedom House. 2005. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

The vast majority of governors were corrupt, ruling their regions as tyrants for their personal benefit and that of their closest allies.

- Arslanbenzer, Hakan (November 14, 2019). "Dzhokhar Dudayev: Fighting for a free Chechnya". Daily Sabah. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- Fuller, Liz (August 30, 2006). "Khasavyurt Accords Failed To Preclude A Second War". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- Stanley, Alessandra (May 13, 1997). "Yeltsin Signs Peace Treaty With Chechnya". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- Sinelschikova, Yekaterina (December 31, 2019). "How Boris Yeltsin, Russia's first president, resigned". Russia Behind the Headlines. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- "Aslan Maskhadov". The Telegraph. March 9, 2005. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- René, De La Pedraja (2018). The Russian Military Resurgence: Post-Soviet Decline and Rebuilding, 1992-2018. McFarland & Company. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1-47666-991-5.

- Williams, Daniel (February 7, 2000). "Russians Capture Grozny". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- Hoffman, David (June 9, 2000). "Putin Lays Direct Rule on Chechnya". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Aris, Ben (March 24, 2003). "Boycott call in Chechen poll ignored". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Bohlen, Celestine (March 9, 2000). "Russian Regions Wary as Putin Tightens Control". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Chuman, Mizuki. "The Rise and Fall of Power-Sharing Treaties Between Center and Regions in Post-Soviet Russia" (PDF). Demokratizatsiya: 146.

- Turner, Cassandra (May 2018). ""We Never Said We're Independent": Natural Resources, Nationalism, and the Fight for Political Autonomy in Russia's Regions": 49. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Federation Council Backs Power-Sharing Bill". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. July 11, 2007. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- Shtepa, Vadim (April 4, 2017). "The Devolution of Russian Federalism". Jamestown. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Malashenko, Alexey (January 25, 2010). "Mintimer Shaimiev Steps Down as President of Tatarstan". Carnegie Moscow Center. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Barry, Ellen (July 13, 2010). "Russian Regional Strongman to Retire". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- Avdaliani, Emil (August 14, 2017). "No Longer the Russian Federation: A Look at Tartarstan". Georgia Today. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Simardone, Aidan (July 27, 2018). "Russian Federation No Longer: The Decline of Federalism and Autonomy in Russia". NATO Association. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- "Tatarstan Vote Seen As Test For Russian Regional 'President'". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. September 15, 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Article 68 of the Constitution of Russia

- Solnick, Steven (May 29, 1996). "Asymmetries in Russian Federation Bargaining" (PDF). The National Council for Soviet and East European Research.

- Martinez-Vazquez, Jorge; Boex, Jameson (2001). Russia's Transition to a New Federalism. Washington D.C., United States: International Bank for Reconstruction. p. 4. ISBN 0-8213-4840-X.

- Solnick, Steven (May 30, 1996). "Center-Periphery Bargaining in Russia: Assessing Prospects of Federal Stability" (PDF). The National Council for Soviet and East European Research: 4.

- Alexander, James (2004). "Federal Reforms in Russia: Putin's Challenge to the Republics" (PDF). Demokratizatsiya: 237 – via Semantic Scholar.

- Kempton, Daniel; Clark, Terry (2002). Unity or Separation: Center-Periphery Relations in the Former Soviet Union. Westport, United States: Praeger. p. 77. ISBN 0-275-97306-9.

- Drobizheva, Leokadia (April 1998). "Power Sharing in the Russian Federation: the View from the Center and from the Republics" (PDF). Preventing of Deadly Conflicts: 12.

- Sergunin, Alexander (2016). Explaining Russian Foreign Policy Behavior: Theory and Practice. Stuttgart, Germany: Ibidem. p. 185. ISBN 978-3-8382-6782-1.

- Kempton, Daniel; Clark, Terry (2002). Unity or Separation: Center-Periphery Relations in the Former Soviet Union. Westport, United States: Praeger. pp. 39–40. ISBN 0-275-97306-9.

- Wegren, Stephen (2015). Putin's Russia: Past Imperfect, Future Uncertain. Lanham, United States: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-4422-3919-7.

- Sharafutdinova, Gulnaz (2013). "Gestalt Switch in Russian Federalism: The Decline in Regional Power under Putin". Comparative Politics. 45 (3): 357–376. JSTOR 43664325.

- Shtepa, Vadim (July 16, 2018). "Russian Federal Districts as Instrument of Moscow's Internal Colonization". Jamestown. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Goode, J. Paul (2011). The Decline of Regionalism in Putin's Russia: Boundary Issues. Abingdon, United Kingodm: Routledge. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-203-81623-3.

- The Territories of the Russian Federation 2009. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge. 2009. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-857-43517-7.

- Russel, Martin (October 20, 2015). "Russia's constitutional structure: Federal in form, unitary in function" (PDF). European Parliamentary Research Service: 1.

- "Regional presidents to choose new job titles". RT International. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- Hauer, Neil (August 1, 2018). "Putin's Plan to Russify the Caucasus". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- Coalson, Robert; Lyubimov, Dmitry; Alpaut, Ramazan (June 20, 2018). "A Common Language: Russia's 'Ethnic' Republics See Language Bill As Existential Threat". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- Guillory, Sean (September 21, 2016). "How 'separatists' are prosecuted in Russia: Independent lawyers on one of Russia's most controversial statutes". Meduza. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Bell, Imogen (2003). The Territories of the Russian Federation 2003. London, United Kingdom: Europa Publications. p. 78. ISBN 1-85743-191-X.

- "Russia broadens anti-incitement law to include separatism". The Times of Israel. July 5, 2014. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Gutterman, Steve; Polityuk, Pavel (March 18, 2014). "Putin signs Crimea treaty as Ukraine serviceman dies in attack". Reuters. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Luhn, Alec (March 18, 2014). "Red Square rally hails Vladimir Putin after Crimea accession". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Charbonneau, Louis; Donath, Mirjam (March 27, 2014). "U.N. General Assembly declares Crimea secession vote invalid". Reuters. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- "2010 All-Russian Population Census" (PDF). All-Russian Population Census (in Russian). December 22, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- Smith, Gordon (1999). State-Building in Russia: The Yeltsin Legacy and the Challenge of the Future. Armonk, United States: M.E. Sharpe. p. 62. ISBN 0-7656-0276-8.

- Grenoble, Lenore (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Hanover, United States: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 69. ISBN 0-306-48083-2.

- Rupen, Robert (1964). Uralic and Altaic Series. 37. Indianapolis, United States: Indiana University. p. 468.

- "Decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee on 04/21/1925 "On the transformation of the Chuvash Autonomous Region into the Chuvash Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic"". Legal Russia (in Russian). Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- Goble, Paul (November 3, 2015). "Why are Only Some Non-Russian Republics Led by Members of Their Titular Nationalities?". The Interpreter. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Paxton, John (1988). The Statesman’s Year-Book Historical Companion. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-349-19448-3.

- Zurcher, Christoph (2007). The Post-Soviet Wars: Rebellion, Ethnic Conflict, and Nationhood in the Caucasus. New York, United States: New York University Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-8147-9724-2.

- Jung, Hakyung (2012). "Language in a Borderland: On the Official Status of Karelian Language". Slavic Studies: 1 and 13 – via Academia.

- Ilič, Melanie (2006). Stalin's Terror Revisited. New York, United States: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-230-59733-4.

- Orttung, Robert; Lussier, Danielle; Paretskaya, Anna (2000). The Republics and Regions of the Russian Federation: A Guide to Politics, Policies, and Leaders. New York, United States: EastWest Institute. pp. 523–524. ISBN 0-7656-0559-7.

- Rubin, Barnett; Snyder, Jack (2002). Post-Soviet Political Order. New York, United States: Routledge. pp. 69. ISBN 0-415-17069-9.

- Shlapentokh, Vladimir; Joshau, Woods (2007). Contemporary Russia as a Feudal Society: A New Perspective on the Post-Soviet Era. New York, United States: Springer. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-0-230-60969-3.

- Ross, Cameron (2003). Federalism and Democratisation in Russia. Manchester, United Kingdom: Manchester University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-7190-5869-1.

- "25 years ago Chukotka withdrew from the Magadan Region". Vesma Today. September 29, 2017. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- Kolguyev, Georgy (November 17, 2005). "Nenets Republic - It Sounds Weird". Nyaryana Vynder (in Russian). Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- Roeder, Philip (2007). Where Nation-States Come From: Institutional Change in the Age of Nationalism. Princetown, United States: Princeton University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-691-12728-6.

- Taagepera, Rein (2013). The Finno-Ugric Republics and the Russian State. New York, United States: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-91977-0.

A proposal to divide Mordovia into Erzyan and Mokshan parts was rejected, 628-34 (Mokshin 1995).

- Южная Осетия хочет войти в состав России // НТВ.Ru

- "ВЕДОМОСТИ – Приднестровье как Крым". Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "ВЗГЛЯД / СМИ: Приднестровье хочет войти в состав России вслед за Крымом". Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- http://dknews.kz/karakalpakiya-hochet-v-rossiyu/

- https://qna.center/get_link?id=7914

- Kenan Aliev. "Мои новости". Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "Гагаузская автономия в Молдавии может объявить о своей независимости". Life.ru. April 1, 2014. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "Тулбуре: Гагаузия может провести референдум и попроситься в состав России " Gagauzinfo.md – Информационный портал Гагаузии №1". Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "Гагаузы с удовольствием войдут в состав России, считает депутат Госдумы". Retrieved May 7, 2016.

External links

![]()