Moksha language

The Moksha language (Moksha: мокшень кяль, romanized: mokšenj kälj, mokšeny käly, [ˡmɔkʃenʲ kælʲ]) is a member of the Mordvinic branch of the Uralic languages, with around 2,000 native speakers (2010 Russian census). Moksha is the majority language in the western part of Mordovia.[4] Its closest relative is the Erzya language, with which it is not mutually intelligible. Moksha is also considered to be closely related to the extinct Meshcherian and Muromian languages.[5]

| Moksha | |

|---|---|

| mokšenj kälj | |

| мокшень кяль | |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | European Russia |

| Ethnicity | Mokshas |

Native speakers | 430,000 Mordvin (2010 census)[1] The 1926 census found that approximately 1/3 of ethnic Mordvins were Moksha, and the figure might be similar today[2] |

| Cyrillic | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Mordovia (Russia) |

| Regulated by | Mordovian Research Institute of Language, Literature, History and Economics |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | mdf |

| ISO 639-3 | mdf |

| Glottolog | moks1248[3] |

Official status

Moksha is one of the three official languages in Mordovia (the others being Erzya and Russian). The right to one's own language is guaranteed by the Constitution of the Mordovia Republic.[6] The republican law of Mordovia N 19-3 issued in 1998[7] declares Moksha one of its state languages and regulates its usage in various spheres: in state bodies such as Mordovian Parliament, official documents and seals, education, mass-media, information about goods, geographical names, road signs. However, the actual usage of Moksha and Erzya is rather limited.

Education

The first few Moksha schools were devised in the 19th century by Russian Christian missionaries. Since 1973 Moksha language was allowed to be used as language of instruction in first 3 grades of elementary school in rural areas and as a subject on a voluntary basis.[8] The medium in universities of Mordovia is Russian, but the philological faculties of Mordovian State University and Mordovian State Pedagogical Institute offer a teacher course of Moksha.[9][10] Mordovian State University also provides a course of Moksha for other humanitarian and some technical specialities.[10] According to the annual statistics of the Russian Ministry of Education in 2014-2015 year there were 48 Moksha-medium schools (all in rural areas) where 644 students were taught, and 202 schools (152 in rural areas) where Moksha was studied as a subject by 15,783 students (5,412 in rural areas).[11] Since 2010, study of Moksha in schools of Mordovia is not compulsory, but can be chosen only by parents.[12]

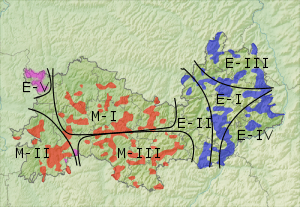

Dialects

The Moksha languages is divided into three dialects:

- Central group (M-I)

- Western group (M-II)

- South-Eastern group (M-III)

The dialects may be divided with another principle depending on their vowel system:

- ä-dialect: Proto-Moksha *ä /æ/ is retained: śeĺmä /sʲelʲmæ/ "eye", t́äĺmä /tʲælʲmæ/ "broom", ĺäj /lʲæj/ "river".

- e-dialect: Proto-Moksha *ä is raised and merged with *e: śeĺme /sʲelʲme/ "eye", t́eĺme /tʲelʲme/ "broom", ĺej /lʲej/ "river".

- i-dialect: Proto-Moksha *ä is raised to /e/, while Proto-Moksha *e is raised to /i/ and merged with *i: śiĺme /sʲilʲme/ "eye", t́eĺme /tʲelʲme/ "broom", ĺej /lʲej/ "river".

The standard literary Moksha language is based on the central group with ä (particularly the dialect of Krasnoslobodsk).

Phonology

Vowels

There are eight vowels with limited allophony and reduction of unstressed vowels. Moksha has lost the original Uralic system of vowel harmony but maintains consonant-vowel harmony (palatalized consonants go with front vowels, non-palatalized with non-front).

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | /i/ ⟨i⟩ ⟨и⟩ |

[ɨ] ⟨į⟩ ⟨ы⟩ |

/u/ ⟨u⟩ ⟨у, ю⟩ |

| Mid | /e/ ⟨e⟩ ⟨е, э⟩ |

/ə/ ⟨ə⟩ ⟨а, о, е⟩ |

/o/ ⟨o⟩ ⟨о⟩ |

| Open | /æ/ ⟨ä⟩ ⟨я, э, е⟩ |

/ɑ/ ⟨a⟩ ⟨а⟩ |

There are some restrictions for the occurrence of vowels within a word:[13]

- [ɨ] is an allophone of the phoneme /i/ after phonemically non-palatalized ("hard") consonants.[14]

- /e/ does not occur after non-palatalized consonants, only after their palatalized ("soft") counterparts.

- /a/ and /æ/ do not fully contrast after phonemically palatalized or non-palatalized consonants.

- Similar to /e/, /æ/ does not occur after non-palatalized consonants either, only after their palatalized counterparts.

- After palatalized consonants, /æ/ occurs at the end of words, and when followed by another palatalized consonant.

- /a/ after palatalized consonants occurs only before non-palatalized consonants, i.e. in the environment /CʲaC/.

- The mid vowels' occurrence varies by the position within the word:

- In native words, /e, o/ are rare in the second syllable, but common in borrowings from e.g. Russian.

- /e, o/ are never found in the third and following syllables, where only /ə/ occurs.

- /e/ at the end of words is only found in one-syllable words (e.g. ве /ve/ "night", пе /pe/ "end"). In longer words, word-final ⟨е⟩ always stands for /æ/ (e.g. веле /velʲæ/ "village", пильге /pilʲɡæ/ "foot, leg").[15]

Unstressed /ɑ/ and /æ/ are slightly reduced and shortened [ɑ] and [æ̆].

Consonants

There are 33 consonants in Moksha.

| Labial | Dental | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | palat. | |||||||||||

| Nasal | m ⟨м⟩ |

n ⟨н⟩ |

nʲ ⟨нь⟩ |

|||||||||

| Stop | p ⟨п⟩ | b ⟨б⟩ |

t ⟨т⟩ | d ⟨д⟩ |

tʲ ⟨ть⟩ | dʲ ⟨дь⟩ |

k ⟨к⟩ | ɡ ⟨г⟩ | ||||

| Affricate | ts ⟨ц⟩ | tsʲ ⟨ць⟩ | tɕ ⟨ч⟩ | |||||||||

| Fricative | f ⟨ф⟩ | v ⟨в⟩ |

s ⟨с⟩ | z ⟨з⟩ |

sʲ ⟨сь⟩ | zʲ ⟨зь⟩ |

ʂ~ʃ ⟨ш⟩ | ʐ~ʒ ⟨ж⟩ |

ç ⟨йх⟩ | x ⟨х⟩ | ||

| Approximant | l̥ ⟨лх⟩ | l ⟨л⟩ |

l̥ʲ ⟨льх⟩ | lʲ ⟨ль⟩ |

j ⟨й⟩ |

|||||||

| Trill | r̥ ⟨рх⟩ | r ⟨р⟩ |

r̥ʲ ⟨рьх⟩ | rʲ ⟨рь⟩ |

||||||||

/ç/ is realized as a sibilant [ɕ] before the plural suffix /-t⁽ʲ⁾/ in south-east dialects.[16]

Palatalization, characteristic of Uralic languages, is contrastive only for dental consonants, which can be either "soft" or " hard". In Moksha Cyrillic alphabet the palatalization is designated like in Russian: either by a "soft sign" ⟨ь⟩ after a "soft" consonant or by writing "soft" vowels ⟨е, ё, и, ю, я⟩ after a "soft" consonant. In scientific transliteration the acute accent or apostrophe are used.

All other consonants have palatalized allophones before the front vowels /æ, i, e/ as well. The alveolo-palatal affricate /tɕ/ lacks non-palatalized counterpart, while postalveolar fricatives /ʂ~ʃ, ʐ~ʒ/ lack palatalized counterparts.

Devoicing

Unusually for a Uralic language, there is also a series of voiceless liquid consonants: /l̥ , l̥ʲ, r̥ , r̥ʲ/ ⟨ʀ, ʀ́, ʟ, ʟ́⟩. These have arisen from Proto-Mordvinic consonant clusters of a sonorant followed by a voiceless stop or affricate: *p, *t, *tʲ, *ts⁽ʲ⁾, *k.

Before certain inflectional and derivational endings, devoicing continues to exist as a phonological process in Moksha. This affects all other voiced consonants as well, including the nasal consonants and semivowels. No voiceless nasals are however found in Moksha: the devoicing of nasals produces voiceless oral stops. Altogether the following devoicing processes apply:

| Plain | b | m | d | n | dʲ | nʲ | ɡ | l | lʲ | r | rʲ | v | z | zʲ | ʒ | j |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devoiced | p | t | tʲ | k | l̥ | l̥ʲ | r̥ | r̥ʲ | f | s | sʲ | ʃ | ç | |||

E.g. before the nominative plural /-t⁽ʲ⁾/:

- кал /kal/ "fish" : калхт /kal̥t/ "fish"

- лем /lʲem/ "name" : лепть /lʲeptʲ/ "names"

- марь /marʲ/ "apple" : марьхть /mar̥ʲtʲ/ "apples"

Devoicing is however morphological rather than phonological, due to the loss of earlier voiceless stops from some consonant clusters, and due to the creation of new consonant clusters of voiced liquid + voiceless stop. Compare the following oppositions:

- калне /kalnʲæ/ "little fish" : калхне /kal̥nʲæ/ (< *kal-tʲ-nʲæ) "these fish"

- марьне /marʲnʲæ/ "my apples" : марьхне /mar̥ʲnʲæ/ ( < *marʲ-tʲ-nʲæ) "these apples"

- кундайне /kunˈdajnʲæ/ "I caught it" : кундайхне /kunˈdaçnʲæ/ ( < *kunˈdaj-tʲ-nʲæ) "these catchers"

Stress

Non-high vowels are inherently longer than high vowels /i, u, ə/ and tend to draw the stress. If a high vowel appears in the first syllable which follow the syllable with non-high vowels (especially /a/ and /æ/), then the stress moves to that second or third syllable. If all the vowels of a word are either non-high or high, then the stress falls on the first syllable.[17]

Stressed vowels are longer than unstressed ones in the same position like in Russian. Unstressed vowels undergo some degree of vowel reduction.

Grammar

Morphosyntax

Like other Uralic languages, Moksha is an agglutinating language with elaborate systems of case-marking and conjugation, postpositions, no grammatical gender, and no articles.[18]

Case

Moksha has 13 productive cases, many of which are primarily locative cases. Locative cases in Moksha express ideas that Indo-European languages such as English normally code by prepositions (in, at, toward, on, etc.).

However, also similarly to Indo-European prepositions, many of the uses of locative cases convey ideas other than simple motion or location. These include such expressions of time (e.g. on the table/Monday, in Europe/a few hours, by the river/the end of the summer, etc. ), purpose (to China/keep things simple), or beneficiary relations. Some of the functions of Moksha cases are listed below:

- Nominative, used for subjects, predicatives and for other grammatical functions.

- Genitive, used to code possession.

- Allative, used to express the motion onto a point.

- Elative, used to code motion off from a place.

- Inessive, used to code a stationary state, in a place.

- Ablative, used to code motion away from a point or a point of origin.

- Illative, used to code motion into a place.

- Translative, used to express a change into a state.

- Prolative, used to express the idea of "by way" or "via" an action or instrument.

- Lative, used to code motion towards a place.

There is controversy about the status of the three remaining cases in Moksha. Some researchers see the following three cases as borderline derivational affixes.

- Comparative, used to express a likeness to something.

- Caritive (or abessive), used to code the absence of something.

- Causal, used to express that an entity is the cause of something else.

| Case function | Case Name[18] | Suffix | Vowel stem

( moдa /ˈmodɑ/ 'land') |

Plain consonant stem

( kyд /kud/ 'house') |

Palatalized consonant stem

( веле /ˈvelʲæ/ 'town') | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /ˈmodɑ-/ | land | /kut-/ | house | /velʲ-/ | town | |||

| Grammatical | Nominative | -Ø | ˈmodɑ | a land | kud | a house | ˈvelʲæ | a town |

| Genitive | -nʲ | ˈmodɑnʲ | of a land / a land's | ˈkudʲənʲ | of a house / a house's | ˈvelʲənʲ | of a town / a town's | |

| Locative | Allative | -nʲdʲi | ˈmodɑnʲdʲi | onto a land | ˈkudənʲdʲi | onto a house | ˈvelʲənʲdʲi | onto a town |

| Elative | -stɑ | ˈmodɑstɑ | off from a land | kutˈstɑ | off from a house | ˈvelʲəstɑ | off from a town | |

| Inessive | -sɑ | ˈmodɑsɑ | in a land | kutˈsɑ | in a house | ˈvelʲəsɑ | in a town | |

| Ablative | -dɑ/-tɑ | ˈmodɑdɑ | from a land | kutˈtɑ | from the house | ˈvelʲədɑ | from the town | |

| Illative | -s | ˈmodɑs | into a land | kuts | into a house | ˈvelʲəs | into a town | |

| Prolative | -vɑ/-ɡɑ | ˈmodɑvɑ | through/alongside a land | kudˈɡɑ | through/alongside a house | ˈvelʲəvɑ | through/alongside a town | |

| Lative | -v/-u/-i | ˈmodɑv | towards a land | ˈkudu | towards a house | ˈvelʲi | towards a town | |

| Other | Translative | -ks | ˈmodɑks | becoming/as a land | ˈkudəks | becoming/as a house | ˈvelʲəks | becoming a town / as a town |

| Comparative | -ʃkɑ | ˈmodɑʃkɑ | the size of a land | kudəʃˈkɑ | the size of a house | ˈvelʲəʃkɑ | the size of a town | |

| Caritive | -ftəmɑ | ˈmodɑftəmɑ | without a land / landless | kutftəˈmɑ | without a house / houseless | ˈvelʲəftəma | without a town / townless | |

| Causal | -ŋksɑ | ˈmodɑŋksɑ | because of a land | kudəŋkˈsɑ | because of a house | ˈvelʲəŋksɑ | because of a town | |

Relationships between locative cases

As in other Uralic languages, locative cases in Moksha can be classified according to three criteria: the spatial position (interior, surface, or exterior), the motion status (stationary or moving), and within the latter, the direction of the movement (approaching or departing). The table below shows these relationships schematically:

| Spatial Position | Motion Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stationary | Moving | ||

| approaching | departing | ||

| Interior | inessive ('in')

-sɑ |

illative ('into')

-s |

ablative ('from')

-dɑ/-tɑ |

| Surface | NA | allative ('onto')

-nʲdʲi |

elative ('off from')

-stɑ |

| Exterior | prolative ('by')

-vɑ/-ɡɑ |

lative ('towards')

-v/-u/-i |

NA |

Pronouns

| Case | Singular | Plural | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First (I) | Second (you) | Third (s/he or it) | First (we) | Second (you all) | Third (they) | |

| nominative | mon | ton | son | miń

/minʲ/ |

t'iń

/tʲinʲ/ |

śiń

/sʲinʲ/ |

| genitive | moń

/monʲ/ |

toń

/tonʲ/ |

soń

/sonʲ/ | |||

| allative | mońd'əjńä or t'ejnä

/monʲdʲəjnʲæ/ /tʲejnæ/ |

tońd'əjt' or t'ejt'

/ˈtonʲdʲəjtʲ/ /tʲəjtʲ/ |

sońd'əjza or t'ejnza

/ˈsonʲdʲəjzɑ/ /ˈtʲejnzɑ/ |

mińd'əjńek

/minʲdʲəjnʲek/ |

tińd'əjńt'

/tinʲdʲəjnʲtʲ/ |

śińd'əjst

/sʲinʲdʲəst/ |

| ablative | mońd'ədən

/ˈmonʲdʲədən/ |

tońd'ədət

/ˈtonʲdʲədət/ |

sońd'ədənza

/ˈsonʲdʲədənzɑ/ |

mińd'ədənk

/minʲdʲənk/ |

mińd'ədənt

/minʲdʲədent/ |

śińd'ədəst

/sʲinʲdʲədəst/ |

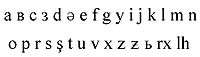

Writing system

.svg.png)

Moksha has been written using Cyrillic with spelling rules identical to those of Russian since the 18th century and as a consequence of that vowels /e, ɛ, ə/ are not differentiated in a straightforward way,[19] however they can be predicted more or less from Moksha phonotactics. The 1993 spelling reform defines that /ə/ in the first (either stressed or unstressed) syllable must be written with the "hard" sign ⟨ъ⟩ (e.g. мъ́рдсемс mə́rdśəms "to return", formerly мрдсемс). The version of the Moksha Cyrillic alphabet used in 1924-1927 had several extra letters, either digraphs or single letters with diacritics.[20] Although the use of the Latin script for Moksha was officially approved by the CIK VCKNA (General Executive Committee of the All Union New Alphabet Central Committee) on June 25, 1932, it was never implemented.

| Cyr | Аа | Бб | Вв | Гг | Дд | Ее | Ёё | Жж | Зз | Ии | Йй | Кк | Лл | Мм | Нн | Оо | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | a | b | v | ɡ | d | ʲe, | je, | ʲɛ, | ʲə | ʲo, | jo | ʒ | z | i | j | k | l | m | n | o, | ə |

| ScTr | a | b | v | g | d | ˊe, | je, | ˊä, | ˊə | ˊo, | jo | ž | z | i | j | k | l | m | n | o, | ə |

| Cyr | Пп | Рр | Сс | Тт | Уу | Фф | Хх | Цц | Чч | Шш | Щщ | Ъъ | Ыы | Ьь | Ээ | Юю | Яя | ||||

| IPA | p | r | s | t | u | f | x | ts | tɕ | ʃ | ɕtɕ | ə | ɨ | ʲ | e, | ɛ | ʲu, | ju | ʲa, | æ, | ja |

| ScTr | p | r | s | t | u | f | χ | c | č | š | šč | ə | i͔ | ˊ | e, | ä | ˊu, | ju | ˊa, | ˊä, | ja |

| IPA | a | ʲa | ja | ɛ | ʲɛ | b | v | ɡ | d | dʲ | e | ʲe | je | ʲə | ʲo | jo | ʒ | z | zʲ | i | ɨ | j | k | l | lʲ | l̥ | l̥ʲ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyr | а | я | я | э | я, | е | б | в | г | д | дь | э | е | е | е | ё | ё | ж | з | зь | и | ы | й | к | л | ль | лх | льх |

| ScTr | a | ˊa | ja | ä | ˊä | b | v | g | d | d́ | e | ˊe | je | ˊə | ˊo | jo | ž | z | ź | i | i͔ | j | k | l | ľ | ʟ | ʟ́ | |

| IPA | m | n | o | p | r | rʲ | r̥ | r̥ʲ | s | sʲ | t | tʲ | u | ʲu | ju | f | x | ts | tsʲ | tɕ | ʃ | ɕtɕ | ə | |||||

| Cyr | м | н | о | п | р | рь | рх | рьх | с | сь | т | ть | у | ю | ю | ф | х | ц | ць | ч | ш | щ | о, | ъ,* | a,* | и* | ||

| ScTr | m | n | o | p | r | ŕ | ʀ | ʀ́ | s | ś | t | t́ | u | ˊu | ju | f | χ | c | ć | č | š | šč | ə | |||||

Literature

Before 1917 about 100 books and pamphlets mostly of religious character were published. More than 200 manuscripts including at least 50 wordlists were not printed. In the 19th century the Russian Orthodox Missionary Society in Kazan published Moksha primers and elementary textbooks of the Russian language for the Mokshas. Among them were two fascicles with samples of Moksha folk poetry. The great native scholar Makar Evsevyev collected Moksha folk songs published in one volume in 1897. Early in the Soviet period, social and political literature predominated among published works. Printing of Moksha language books was all done in Moscow until the establishment of the Mordvinian national district in 1928. Official conferences in 1928 and 1935 decreed the northwest dialect to be the basis for the literary language.

Common expressions (Moksha–Russian–English)

| Moksha | Transliteration | Russian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| И́на | Ína | Да | Yes |

| Э́ле | Éle | Да | Yes |

| Пара | Para | Ладно | Good |

| Аф | Af | Не | Not |

| Аш | Aš | Нет | No |

| Шумбра́т! | Šumbrát! | Здравствуй! | Hello! (addressing one person) |

| Шумбра́тада! | Šumbrátada! | Здравствуйте! | Hello! (addressing more than one person) |

| Сюк(пря)! | Sük(prä)! | Привет! ("поклон"), Добро пожаловать! | Hi! (Welcome!) |

| Ульхть шумбра́! | Ulyhty šumbrá! | Будь здоров! | Bless you! |

| У́леда шумбра́т! | Úleda šumbrát! | Будьте здоровы! | Bless you (to many)! |

| Ко́да те́фне? | Kóda téfne? | Как дела? | How are your things getting on/How are you? |

| Ко́да э́рят? | Kóda érät? | Как поживаешь? | How do you do? |

| Лац! Це́бярьста! | Lac! Cébärysta! | Неплохо! Замечательно! | Fine! Very good! |

| Ня́емозонк! | Näjemozonk! | До свидания! | Good bye! |

| Ва́ндыс! | Vándys! | До завтра! | See you tomorrow! |

| Шумбра́ста па́чкодемс! | Šumbrásta páčkodems! | Счастливого пути! | Have a good trip/flight! |

| Па́ра а́зан - ле́здоманкса! - се́мбонкса! | Para ázan - lézdomanksa! - sémbonksa! | Благодарю - за помощь! - за всё! | Thank you - for help/assistance! - for everything! |

| Аш ме́зенкса! | Aš mézenksa! | Не за что! | Not at all! |

| Простямак! | Prostämak! | Извини! | I'm sorry! |

| Простямасть! | Prostämasty! | Извините! | I'm sorry (to many)! |

| Тят кя́жиякшне! | Tät käžiäkšne! | Не сердись! | I didn't mean to hurt you! |

| Ужя́ль! | Užäly! | Жаль! | It's a pity! |

| Ко́да тонь ле́мце? | Kóda tony lémce? | Как тебя зовут? | What is your name? |

| Монь ле́мозе ... | Mony lémoze ... | Меня зовут ... | My name is ... |

| Мъзя́ра тейть ки́зa? | Mâzära tejty kíza? | Сколько тебе лет? | How old are you? |

| Мъзя́ра тейнза ки́за? | Mâzära teinza kíza? | Сколько ему (ей) лет? | How old is he (she)? |

| Те́йне ... ки́зот. | Téjne ... kízot. | Мне ... лет. | I'm ... years old. |

| Те́йнза ... ки́зот. | Téjnza ... kízot. | Ему (ей) ... лет. | He (she) is ... years old. |

| Мярьгат сува́мс? | Märygat suváms? | Разреши войти? | May I come in? |

| Мярьгат о́замс? | Märygat ozams? | Разреши сесть? | May I have a seat? |

| О́зак. | Ózak. | Присаживайся. | Take a seat. |

| О́зада. | Ózada. | Присаживайтесь. | Take a seat (to more than one person). |

| Учт аф ла́мос. | Učt af lámos. | Подожди немного. | Please wait a little. |

| Мярьк та́ргамс? | Märyk tárgams? | Разреши закурить? | May I have a smoke? |

| Та́ргак. | Tárgak. | Кури(те). | You may smoke. |

| Та́ргада. | Tárgada. | Курите. | You may smoke (to more than one person). |

| Аф, э́няльдян, тят та́рга. | Af, énälydän, tät tárga. | Нет, пожалуйста, не кури. | Please, don't smoke. |

| Ко́рхтак аф ламода сяда кайгиста (сяда валомня). | Kórhtak af lamoda säda kajgista (säda valomnä). | Говори немного погромче (тише). | Please speak a bit louder (lower). |

| Азк ни́нге весть. | Azk nínge vesty. | Повтори ещё раз. | Repeat one more time. |

| Га́йфтть те́йне. | Gájftty téjne. | Позвони мне. | Call me. |

| Га́йфтеда те́йне. | Gájfteda téjne. | Позвоните мне. | Call me (to more than one person). |

| Га́йфтть те́йне сяда ме́ле. | Gájftty téjne säda méle. | Перезвоните мне позже. | Call me later. |

| Сува́к. | Suvák. | Войди. | Come in. |

| Сува́да. | Suváda. | Войдите. | Come in (to many). |

| Ётак. | Jotak. | Проходи. | Enter. |

| Ётада. | Jotada. | Проходите. | Enter (to many). |

| Ша́чема ши́цень ма́рхта! | Šáčema šíceny márhta! | С днём рождения! | Happy Birthday! |

| А́рьсян тейть па́ваз! | Árysän tejty pávaz! | Желаю тебе счастья! | I wish you happiness! |

| А́рьсян тейть о́цю сатфкст! | Árysän tejty ócü satfkst! | Желаю тебе больших успехов! | I wish you great success! |

| Тонь шумбраши́цень и́нкса! | Tony šumbrašíceny ínksa! | За твое здоровье! | Your health! |

| Од Ки́за ма́рхта! | Od Kíza márhta! | С Новым годом! | Happy New Year! |

| Ро́штува ма́рхта! | Róštuva márhta! | С Рождеством! | Happy Christmas! |

| То́ньге ста́не! | Tónyge stáne! | Тебя также! | Same to you! |

References

- "Population of the Russian Federation by Languages (in Russian)" (PDF). gks.ru. Russian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- Jack Rueter (2013) The Erzya Language. Where is it spoken? Études finno-ougriennes 45

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Moksha". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- Janse, Mark; Sijmen Tol; Vincent Hendriks (2000). Language Death and Language Maintenance. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. A108. ISBN 978-90-272-4752-0.

- (in Russian) Статья 12. Конституция Республики Мордовия = Article 12. Constitution of the Republic of Mordovia

- (in Russian) Закон «О государственных языках Республики Мордовия»

- Isabelle T. Kreindler, The Mordvinians: A doomed Soviet nationality? | Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique. Vol. 26 N°1. Janvier-Mars 1985. pp. 43–62

- (in Russian) Кафедра мокшанского языка Archived 2015-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Russian) Исполняется 15 лет со дня принятия Закона РМ «О государственных языках Республики Мордовия» Archived 2015-06-14 at the Wayback Machine // Известия Мордовии. 12.04.2013.

- "Статистическая информация 2014. Общее образование". Archived from the original on 2018-08-09. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- (in Russian) Прокуратура борется с нарушением законодательства об образовании = The Prosecutor of Mordovia prevents violations against the educational law. 02 February 2010.

- Feoktistov 1993, p. 182.

- Feoktistov 1966, p. 200.

- Feoktistov 1966, p. 200–201.

- Feoktistov 1966, p. 220.

- Raun 1988, p. 100.

- (in Finnish) Bartens, Raija (1999). Mordvalaiskielten rakenne ja kehitys. Helsinki: Suomalais-ugrilaisen Seura. ISBN 9525150224. OCLC 41513429.

- Raun 1988, p. 97.

- Omniglot.com page on the Moksha language

Bibliography

- Aasmäe, Niina; Lippus, Pärtel; Pajusalu, Karl; Salveste, Nele; Zirnask, Tatjana; Viitso, Tiit-Rein (2013). Moksha prosody. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran toimituksia. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. ISBN 978-952-5667-47-9. Retrieved 2014-07-24.

- Feoktistov, Aleksandr; Saarinen, Sirkka (2005). Mokšamordvan murteet [Dialects of Moksha Mordvin]. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran toimituksia (in Finnish). Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. ISBN 952-5150-86-0.

- Juhász, Jenő (1961). Moksa-Mordvin szójegyzék (in Hungarian). Budapest.

- Paasonen, Heikki (1990–1999). Kahla, Martti (ed.). Mordwinisches Wörterbuch. Helsinki.

- Raun, Alo (1988). "The Mordvin Language". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Uralic Languages: Description, History and Foreign Influences. pp. 96–110. ISBN 90-04-07741-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- In Russian

- Аитов Г. Новый алфавит – великая революция на Востоке. К межрайонным и краевой конференции по вопросам нового алфавита. — Саратов: Нижневолжское краевое издательство, 1932.

- Ермушкин Г. И. Ареальные исследования по восточным финно-угорским языкам = Areal research in East Fenno-Ugric languages. — М., 1984.

- Поляков О. Е. Учимся говорить по-мокшански. — Саранск: Мордовское книжное издательство, 1995.

- Феоктистов А. П. Мордовские языки // Языки народов СССР. — Т.3: Финно-угроские и самодийские языки — М., 1966. — С. 172—220.

- Феоктистов А. П. Мордовские языки // Основы финно-угорского языкознания. — М., 1975. — С. 248—345.

- Феоктистов А. П. Мордовские языки // Языки мира: уральские языки. — М., 1993. — С. 174—208.

- Черапкин И. Г. Мокша-мордовско – русский словарь. — Саранск, 1933.

- In Moksha

- Девяткина, Татьяна (2002). Мокшэрзянь мифологиясь [Tatyana Devyatkina. Moksha-Erzya mythology] (in Moksha). Tartu: University of Tartu. ISBN 9985-867-24-6.

External links

| Moksha edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Mokshen Pravda newspaper

- Moksha – Finnish/English dictionary (robust finite-state, open-source)