Roman diocese

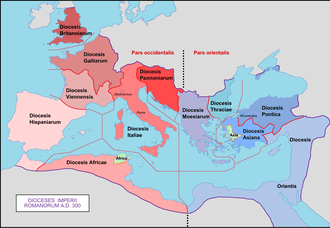

In the Later Roman Empire, usually dated 284 A.D. to 602 A.D., the regional governance district known as the Roman or civil diocese (Latin: dioecēsis, from the Ancient Greek: διοίκησις, 'administration,' 'management,' 'assize district,' group of provinces) was made up of a grouping of provinces headed by vicars (substitutes or representatives) of praetorian prefects (who governed directly the dioceses they were resident in). There were 12 dioceses in the beginning rising to 14 by 380 (in the diocese of Italy there was a vicar in Rome to govern the vicinities of Rome (except Rome itself, assumed by Praefectus Urbi), southern Italy, and Islands, while the prefect governed the northern half, usually from Milan).[1] The civil diocese is not to be confused with earlier judicial districts of the Republic and Early Empire which were carved out from within a province.

The civil diocese was created during the First Tetrarchy, 293–305, the years usually given is 297 A.D., or possibly later as some recent studies suggest in 313/314, but no later than the Verona List securely dated to June 314.[2] The date of creation is still controversial.[3] The diocese was the intermediate level of governance over provinces even more clearly so after the gradual emergence of the three to four territorialized praetorian prefectures.[4] Whether these early prefectures were fully administrative and territorial from 325-330 (as claimed by Zosimus a late 5th-century historian) is the subject of scholarly debate: the early prefectures may have been more 'spheres of control' until the early 340s.[5] One recent study reports that the praetorian prefectures were clearly regionalized in 354.[6]

The main task of the vicars was to control and supervise governors, and coordinate their activities.[7] From inception the vicars had superior authority i.e. appeal authority in their judicial capacity (a common name for governors was iudex, judge) within the prefectures. Constantine extended their authority from the late 320s over the regional districts of the Treasury and Crown Estates, otherwise independent ministries, in matters of appeals legal and fiscal debt appeals[8] In this way by means of a set of overlapping functions and extraordinary jurisdiction vicars and governors could monitor the functioning of the entire administrative apparatus without being able to interfere in the daily operations of the two fiscal ministries.

Although deputies of the prefects, vicars did not duplicate their superiors' roles "in all their manifold functions" because their discretionary authority was carefully circumscribed; and their policy and regulatory making powers nil.[9]

Vicars were always subordinate to the prefects before and after the creation of territorially defined prefectures though "the degree of their subordination at least in some judicial matters is uncertain."[10] In the early 340s an additional security measure was put into place as an internal control means (stemming from a high distrust of intra-departmental self-policing): the appointment of senior agents of the Master of the Offices, (a kind of Minister for Internal Affairs, Administrative Oversight and Communications) as heads of offices of vicars, prefects and two of three proconsuls (the Master from the 330s evolved as the second most powerful civilian official in the government after the prefects). The 'dual' control formed part of the extensive checks-and-balances built into the Roman bureaucratic machine, and was an ancient practice to limit the concentration of power.[11]

The vicar, the comptroller of the Treasury ('rationalis') and the manager of the Crown Estates, ('magister' and from the 350s also 'rationalis' formed the 'executive board' of the diocese. The three regional officials mirrored their superior counterparts at the highest palatine level. The triads' staffs were stationed in all diocesan see cities where vicars were resident. In dioceses prefects governed, normally 2-4, prefects' staffs were enlarged and more complex versions of the diocesan (1500-2000 instead of 300). However, the Treasury and Crown Estates staffs were present in all as constituted.[12] The diocesan-centered policy was gradually and very haltingly reversed (as it in like manner evolved earlier) with the rise of greater centralism from the top palatine level from the mid-360s with the Valentinian Dynasty and especially with Theodosius I, 379–395 in the East.[13]

From the end of the 4th century the vicars were very gradually by-passed operationally, more so in some dioceses than others due to different circumstances, but with little formal regulatory reduction or changes in their responsibilities, judicial or fiscal.[14] Administrative centralization at the top lessened the importance of vicar. The commutation of most in-kind taxes to payment in gold (completed in the West by 425 and in the East by the 480s) simplified the cumbersome tax collection and distribution system (not the calculation of) thereby drastically reducing the previously important role of the vicars as 'fiscal cops.[15] The rate of decline was not uniform but varied depending on the circumstances of each region: the decline in the importance of some vicars and dioceses may have been retarded since some powerful late 4th and early 5th century prefects used them to strengthen their own power over the administration; pressed the vicars to get more performance out of governors; and from the mid-360s used vicars in their efforts to encroach on the prerogatives and independence of the Treasury Ministry and Crown Estates by closer monitoring, supervising and/or direct intervention in the collection of these two ministries' revenues, an effort which was hotly resisted into the 440s (their revenues, line-items in the imperial budgets composed by the prefects' financial departments, were also reporting to them).[16]

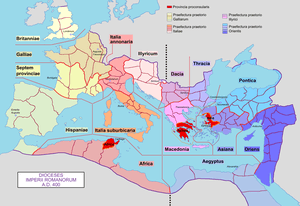

Post-450 there is an accelerated decline in such dioceses as remained. Britain, the Spains, Africa, Illyricum in the West were already gone. The Treasury and Crown Estate regional counterparts were weakened. Although the seven dioceses (five with vicars and two governed by prefects) were still intact in the East, the vicars' responsibilities were progressively taken over, judicially and fiscally, by the reassertion of the two-tier prefect-governor direct governance policy as had existed prior to the early 4th century.[17] However, the vicar (Augustal Prefect) in the rich provinces of Egypt, the Comes Orientis in Antioch in Syria who had critical duties in regard to strategic border defenses with Persia, and the vicar of Rome who played a major roll in provisioning the capital, continued to have importance into the 6th century.[18] Two vicars remained in the West, one for the two Gallic dioceses and one for the southern half of the Diocese of Italy. Justinian abolished the dioceses of the Prefecture of the East, Pontus, Asia and Oriens in 535 and Egypt in 539 on ground of their being moribund, ineffective, corrupt and, therefore, redundant (Anastasius, emperor 491–518, abolished the diocese of Thrace by 500 A.D.).[19] However, by 542 he gave the comes Orientis (vicar) who was also governor of Syria I some control over the northern part of former diocese[20] In 548 he restored the diocese of Pontus: the vicar was mainly a police officer appointed to deal with brigands moving about from province to province. To facilitate this he was given civilian and military powers over soldiers and officials[21] The dates of the abolition of the dioceses of Dacia and Macedonia are unknown. It might have been better to have given the vicars wider powers and discretionary authority[22]

Civil dioceses

Establishment

The earliest use of "diocese" (διοίκησις, dioikesis, Greek for "administration", and hence "province") as an administrative unit was in the Greek-speaking East. The word "diocese", which at that time denoted a tax collection district, came to be applied to the territory itself. In the third century AD the word referred to the subdivision of large provinces subject to administrative reform.[23] Neither of these is the antecedent of the vicariate dioceses whose creation is traditionally attributed to the emperor Diocletian in 297 (although recent studies have shifted the date as far back as 314); the date has been the subject of much debate among scholars for more than 100 years.[24]

The model for the diocesan vicars may be or was the substitute, agens vices praefectorum praetorio ("acting on behalf of the praetorian prefects"), appointed to command units of the Praetorian Guard in the absence of the prefects from Rome: this practice started during the Severan Dynasty, 193–235.[25] In the last decade of the 3rd century four are seen in the provinces on special assignments in North Africa, Egypt, and Anatolia[26]

The vicars were in the beginning mainly judicial/administrative counterparts to the 'fiscal' regional officials, the comptrollers ('rationales') of the Treasury ('Res Summa or Res Sumarum') and managers ('magistri') of the Crown Estates ('Res Privata') with some fiscal responsibilities which were enhanced in several ways between 325–329.

Regional 'fiscal' dioceses first appeared in 286 in the second year of Diocletian's reign. These were headed by comptrollers ('rationales') of the Treasury.[27] They may be the models for the vicariate dioceses. The model for the vicariate diocese may be the pre-existing regional fiscal district of Egypt, Cyrenaica and Crete of the 'Res Summa,' the Treasury, and 'Res Privata,' the Crown Estates, which Diocletian from 286 made empire-wide.[28]

The provinces, even though doubled from 47 to 100 from the early 290s to 305 for the purposes of increased efficiency and control, remained the principal units of administration. However, the creation of 'vicariate' regional dioceses (sometime between 297 and 313-14) heralded a major and deliberate innovation in the way the Empire would be governed in the "regionally based centralism" favored by the Constantinian Dynasty (312-363).[29] The policy shift toward regionalism did not spring into existence all at once: it may have been one result of a slow shift from governance from the city of Rome that began with Marcus Aurelius due to the need of emperors being on the frontiers and on the move.[30] The regional policy came to fruition with Constantine's rationalization of the competencies of the major palatine ministries and the reduction of the prefects' responsibilities in the years 325–329.[31] These changes gave vicars more effective control over the diocesan administrative apparatus than they had possessed when dioceses were created, especially in fiscal matters, to the detriment of the Treasury comptrollers.[32]

Reforms of Diocletian and the Appearance of Regional Fiscal Units

In 287 Diocletian initiated a partial reorganization of the Roman Empire's administrative and tax assessment systems which remained in force though modified in its essential components for more than three centuries. This included a set of empire-wide regional censuses as a part of campaign to repair and stabilize the finances of the State. For over 50 years the Empire had been threatened foreign invasions, usurpations and economic decline which threatened the unity and existence of the Empire.[33] One result of fiscal reform was a regular budget in the modern sense for the first time (with adjustable rates and other means of revision not previously not available with the inflexible financial regime of the Principate).[34] Several other measures were undertaken between 293-298 during the First Tetrarchy, 293–305. He placed the mints near large concentrations of troops. He tried to centralize the administration of justice in the governors (instead of assigning lesser cases to their legal assistants, the 'iudices pedanei'). He continued the process of separating military command from governors that was completed early in the reign of Constantine. Thereafter all governors (prefects, vicars and proconsuls) were purely civilian officials. To facilitate governance and control of the vast empire he created the First Tetrarchy, 293–305. There were two senior Emperors, the Augusti; each governed half the empire. Each was served by a junior emperor, titled Caesar. Each emperor was served by a prefect; none for the Caesars.[35]

Diocletian increased the number of provinces from 47 in 284 in order to enhance control of the central government and make tax collection easier;[36] and to give the governors more time to fulfill their duties in smaller provinces with fewer inhabitants.[37] By the end of the reign they numbered 104. The provinces were in turn grouped into 12 dioceses (Verona List, 2 vicars for the Diocese of Italy), if indeed they were created during his reign and not later. By 327, Moesia had been divided; and Egypt was detached from Oriens in either 370 or 380 an increase from 12 to 14 as recorded in the Notitia Dignitatum circa 395. The diocese of Italy was divided into two with a vicar in Rome and the prefect usually in Milan but when he was in Sirmium in Pannonia there was a vicar in Milan.[38] Trier was the seat of the prefect in the diocese of Gaul until 407 when it was moved to Arles. Constantinople (only designated officially as the second capital in 359) was the usual residence in the Prefecture of the East from 330, and always from 395 (emperors were resident there for only 11 years between 337-380).[39] The largest diocese by number of provinces, not in area, was the Diocese of the East, which included 16 provinces, while the smallest, the Diocese of Britain, had only 4 provinces. One result of the reforms was a greatly increased size of the imperial bureaucracy and its professionalization with a staff made up almost entirely of free men on salary. It was still very small by modern standards, 30–40,000 for a population of 50–60 million (excluding the numerous local managers of the Res Privata).[40]

Constantinian Reforms

Constantine sole emperor from November 324 initiated a reorganization and partial rationalization of the imperial administration. Competencies within the various upper echelon ministries of the administration – these in some instances had become confused. The reforms resulted in greater specialization and definition of responsibilities.[41] He focused on the prefects' role. By the late 3rd century they had become the emperors' vice-regents, "grand viziers," seconds-in-command, whose responsibilities had become too burdensome for the three of them in the year 325.[42] He had already removed their active military commands in 312 after the defeat of Maxentius: henceforth they were purely civilian officials (but still responsible for administration of the military esp. supplies and recruitment.[43] However, they continued to wear the military cloak in purple the imperial color - the only officials allowed this (the vicars had the privilege of wearing the military cloak).[44]

Diocletian earlier had converted an 'ad hoc' liturgy, the 'Annona Militaris,' into a regular tax. The A.M. was a separate line item in the budget and was under the direct control of the praetorian prefects who were still the senior military officers until Constantine made them purely civilian officials in 313. The A.M. originated with the Severan Dynasty, 193-235 A.D. to furnish supplies to the army and for which they supposed to be compensated and which they had to transport the destinations).[45] He split the treasury into three giving the prefects, the SL ('Sacrae Largitiones' from 319, formerly the 'Summae Res') and RP ('Res Privata', the 'Crown Estates') their own treasuries(the accounts were always separate and pains were taken to keep them that way at all levels).[46] He confirmed the independence of the latter two ministries. He removed the prefects' control over the Master of the Offices ('Magister Officiorum'). He was in charge of the palace administration, th imperial secretariats, the corps of courier/security agents, and was nominal commander of the imperial guard. The emperor placed this official in charge of imperial administrative oversight as part of the process of centralization and greater competency definition.[47]

Before Constantine created 'territorial' praetorian prefectures as part of a major reorganization of the top administrative competencies during the years 325-329 (the exact date is the subject of much discussion) dioceses had been the largest territorial governance units.[48] These early prefectures may not have had definitive boundaries like the dioceses, but rather were 'spheres' of control which become more fixed under his successors sons from the 340s.[49] Each prefecture was headed by a powerful Praefectus praetorio the most powerful official after the emperor himself. From 318 there were three prefects. Four are attested to in 331 (in Gaul, Italy, Illyricum and with Constantine in Constantinople; a fifth in Africa 335-337).[50] Thereafter the number varied between three (Gaul, Italy and Africa, the East) and four (Illyricum) until the number was fixed at four in 395. Prefects governed dioceses where they were resident; the other dioceses were governed by a vicarius of a dioecesis, a deputy to a Praefectus praetorio ("Praetorian Prefect"). They shared a portion of the prefects' authority.[51]

Constantine removed the SL from any involvement in the collection and distribution of the in-kind non-monetary taxes of the Annona and the operation of State Post, the 'cursus publicus' (operations and maintenance transferred to the prefecture.[52] Prior to 325 the SL regional comptrollers ('rationales,' accountants) had been ubiquitous in tax collection aided by their subordinate heads of the RP and in the operation of the State Post.[53] Afterwards the SL's role was confined to the supervision of the collection and distribution of revenue from numerous gold and silver taxes and operation of state armories, mills, mints, confiscations, and army uniforms. The last of the SL's provincial procurators were disbanded by 330: most of their tax collection duties were transferred to the governors who were subordinate. The SL regional comptrollers instead dispatched their agents annually to monitor the activity of governors in respect to the taxes due the Treasury (a measure that prefecture and RP copied increasingly as a means of applying control from the central headquarters in addition to and rather than relying solely on permanent regional and provincial staffs).[54]

The emperor, having rationalized the responsibilities among the prefecture, SL and RP, made sure the prefects and vicars could monitor and if need be supervise the two fiscal offices to some degree without being able to interfere in their daily routine operations or divert their incomes from their treasuries to the prefectures. As part of this program between 327-328 he transferred appeals of fiscal debt cases of the sacrae largitiones (the Imperial treasury which collected monetary taxes) and the res privata (the private property of the emperors, i.e. crown estates, whose income was reserved for them, not their personal or family property) to the courts of the vicars, prefects and proconsuls. First instance cases remained with the SL and RP administrative courts.[55] Appeals went to their courts, since the prefects, as heads of finance, composed the annual, universal budgets which were based on dioceses as the fiscal assessment districts for all departments.[56] The additional oversight power did not permit prefectural interference in the daily, routine operations of the SL and RP which were independent ministries under the immediate control of their respective senior comptrollers, who were 'comites' or imperial companions who reported directly to the emperor(s).

The SL's and RP's losses – the narrowed range of responsibilities and monitoring of their activities – was the vicars' gain in terms of administrative control over the diocese. However, the vicars and comptrollers of the SL and RP continued to form a triad of regional officials who worked or were supposed to work closely together. The proximity of their offices located in all but a couple of diocesan see cities facilitated cooperation and efficiency.[57] Indicative of the change is that elevation of vicars from equestrian rank of the second level, 'perfectissumus,' to lowest rank senatorial, 'clarissimus,' in 326 while their fiscal counterparts remained as equestrians for another 40 years and more (except for the comptroller of Egypt).[58]

The vicars had additional means of control in their armature: in matters of criminal and civil justice the vicars already had control over the diocesan staff (and ultimately over the provincial) and those of the sacrae largitiones and res privata in civil and criminal cases;[59] Any action taken by the fiscal office of the SL that could affect provincial populations had to have the prior approval of the emperor or a prefect who would inform the vicars and the governors.[60] Until 355 soldiers charged with criminal and civil offenses were tried in the courts of the prefecture (from 355 defendant soldiers in criminal cases and from 413 in civil cases in courts martial).[61]

Post the reforms of 325-329 the praetorian prefects remained the most senior officials; were the heads of finance and government; were chief justices (they alone apart from the emperors could give final verdicts), and were quartermaster-generals of the army (a means of putting army supply and logistics under civilian control).[62] However they were no longer heads of administration. They had to share the limelight with the heads of the Treasury, the Crown Estates, the Chief Imperial Legal Counsel, the Master of the Offices and the four senior generals who formed the imperial consistory, which the prefects were not members of formally except ex-officio. They were no longer in undisputed control of the imperial government.[63] They were, however, responsible for all levies and current state expenditures,[64] as reflected in the vicar's set of fiscal responsibilities,[65] Prefects received most of their financial information from the vicars and governors.[66]

From 330 armed with greater authority (and with senatorial rank) the vicars entered their heyday which lasted into the early 5th century.[67] Indicative of this situation from 330 or so the word "diocese" is used solely for the vicars' and not for the SL and RP districts.[68] The dioceses functioned more clearly as the intermediate echelon between the provinces and the prefectures, although the hierarchy did not function rigidly in a vertical manner: provincial governors could directly contact the Praefectus praetorio or Emperor and vice versa, as could other higher officials and military officers. Despite the creation of the territorial prefectures, the administrative policy of the Constantinian dynasty, 312–363, was regionally based centralism, i.e. focused on dioceses; this policy was only gradually changed from the 370s.[69] However, in 385 in a small but significant change appeals of fiscal debt cases of the 'Sacrae Largitiones' and 'Res Privata' were again after 55+ years allowed from their provincial and regional administrative courts to the palatine level heads which is one indication of further centralization at the expense of the vicars.[70]

Organisational structure and responsibilities

The vast majority of imperial officials were located in the 125 provincial and diocesan seats and the two imperial capitals in an empire. Most of the population had little contact with imperial officials except when these were sent out from headquarters on special assignments, regularly scheduled business in the fiscal cycle or the governor making a progress through the province to take the assizes.[71]

The dioceses were large regional judicial districts. The vicars were mainly appeal justices and to them were normally directed first appeals within their jurisdictions. A second appeal was allowed and went from their courts to the emperor.[72] If they rejected an appeal it went to the prefect for a final verdict.[73] This remained on the books as the official appeal procedure ('more appellationum') until the reign of Justinian I but in practice it was circumvented from the 360s and increasingly in the 5th century largely because the imperial government had difficulty in controlling the number of appeals as it was almost automatic, litigants tried to by-pass vicars and they other officials with appeal jurisdiction, such as the city prefects, had a habit of passing on provincial and minor courts cases to prefects and emperors in the hope of getting a final decree from them based on the procedure, 'by consultation' ('more consultationum').[74] Vicars also had first instance jurisdiction. Since they (and praetorian and urban prefects) could not reverse the decision of a lower court except on appeal, first instance authority gave them the power to intervene in the event of irregularity or corruption; if they refused an appeal it went to the nearest prefect.[75] Many litigants it seems tried to circumvent the vicars to get a final verdict which irritated the emperors and highest official who had important administrative duties[76] Of importance to understanding the supervisorial authority of the vicars: they were the only officials in the dioceses with appellate jurisdiction with the exception of regions around the two imperial capitals and in diocese governed by prefects.[77]

Dioceses were the great fiscal districts of the Empire which the prefects used to compose the global imperial budgets.[78] They guaranteed the proper assignment of liturgies/munera; their staff investigated tax fraud and performed audits, reviewed financial reports and compiled such for the prefecture.[79] To illustrate the importance of the diocesan district the prefects' financial branches were organized by diocese with a financial secretary, the cura epistolarum and senior accountants, 'numerarii' and was further divided into sections for each province and headed by accountants called, 'tractatores'.[80] The judicial branch was senior to the financial. Although the prefectures each had a central fisc, the arca, they never had local treasuries or reserves such as the SL had at the diocesan level.[81] The vicars also functioned as regional overseers of army supply and logistics (dealt with in practice by the governors, officials of the SL and the army).[82] They were charged with overseeing the movement and provisioning of troops across provincial lines in peace-time and war.

The post of vicar was an honor ('dignitas'). The vicars, unlike their staffs, were not professional bureaucrats whose senior officials ran the office and provided continuity of administration.[83] They rarely served for more than one year though some served in two or three dioceses. They were, for the most part, upper-middle class or aristocrats, most of whom had had previous several years experience on the legal or financial staffs of governors or higher officials before serving as governors (one-year terms). The shortness of the term had much to do with keeping as many plumb jobs open as possible for eligible seekers in a stratified status-conscious society. They were expected to exercise oversight control over the diocesan administrative apparatus on behalf of prefects and emperors: coordinate provincial administration and control governors, regulate the courts, secure the revenue and its proper distribution by the governors, guarantee the proper assignments of liturgies made by the governors, provide logistics support for defense and war preparation; and process masses of information from many civil and military sources for government use at the top echelon.[84] They had staffs of 300 (600 in Oriens) for jurisdictions whose populations numbered 2-12 million.[85] Their office staff, divided into judicial/administrative and financial, processed information, especially fiscal, for use of the highest level palatine level of administration (also relieve emperors and prefects from an overload of judicial business)[86]

The vicars were remote figures to the population. They supervised governors, but did not do their work for them or supervise the local administrations unless intervention was called for: their role was oversight, overall control, regulation. By contrast, the governors, hard-pressed by their duties, had to make do with small staffs of 100 by statute. They were the work horses of the imperial administration who supervised the bedrock of administration of the empire, the city states, and the hundreds of thousands of municipal officials, the town councilors and others of eligible status, who were obligated increasingly from the mid-3rd century to perform numerous tasks, liturgies (previously performed voluntarily for the most part) for the imperial government and their own city states.[87] The emperors as an inducement to the city council members to fulfill their duties and to bind them to the empire opened up employment in the imperial administration to them, which allowed to escape performing imperial liturgies.

Although vicarii were the principal judicial and financial officials of the regions, they had to govern with restricted authority. They were not policy-makers: they executed policy. Their verdicts could be appealed to the emperor or prefect. They had no discretion to change regular and supplemental tax demands, rates and assessments, allocations, remissions or make policy. The lack of discretionary power was a control method to prevent deviation from policy, corruption, try to ensure adequate performance, and the Roman habit of dividing power between two or more officials. On the other hand, the monopolization of decision-making at the very top was a double-edged sword: it promoted adherence to policy and orders, but also fostered confusion within the imperial administration that risked administrative paralysis and resulted in a constant stream of requests for clarification to emperors and their closest advisors and high-level appointees, even on some of the simplest issues.[88]

Vicars, Prefects and Masters of the Offices

In a move to assert more central control over vicars from the early 340s the office head (princeps officii) in each prefecture and diocese and two of three proconsulates (Achaia and Africa, but not Asia) was a senior agent (agens in rebus) of the Master of the Offices ('magister officiorum'). The 'agentes in rebus,' 'men of affairs,' began their service as couriers, and over the course of their service served in various other ministries to gain broad experience and knowledge of the imperial administration and law.[89]

The placements gave the emperors on-the-spot 'watchdogs' over the upper echelons of the administration just as vicars did for prefects. The 'princepes' reported directly to the 'magister officiorum' and to their immediate nominal superiors of the prefecture. In this way, the masters were given an additional measure of control over prefects,[90] vicars and two of three proconsuls. The office head's job was to control the staff, not to do paperwork.[91] The 'princeps' was not under the authority of the vicar. He was not a member of staff, which had its own permanent top four officials. He brought his own personal staff with him.[92]

The post of Master of the Offices, 'magister officiorum,' originally a relatively minor military officer, the tribune commander of the imperial guard, the Scholarians. Constantine in 312-313 made the tribune of head of the imperial secretariats. The additional title of 'magister' (officially, 'tribunus et magister officiorum') appears by 319. The emperor also put him in charge of the corps of imperial couriers, the 'agentes in rebus,' who were organized as cavalry soldiers. He removed the prefect's control over the 'magister' in 325–326 at which time he made him 'comes,' companion of the emperor.[93] The master became a kind of Minister For Internal Security, Administrative Oversight and Communications.[94]

The Master became (or masters since each emperor had one) the emperor's chief administrative aide and watchdog. Although higher ranking imperial officials and military officers could communicate to the emperor directly through the MO (to block information sources was not desirable), routine business from the various ministries (prefectures, SL and RP) was directed to their respective offices, whence it was channeled, if need be, to the masters of the offices and their secretariats attached to the palace. This gave the master a measure of control over prefects,[95] vicars and two of three proconsuls and is another example of an administrative overlap designed to enhance surveillance, security and control.

The 'princeps officii' reported directly to the 'magister officiorum' and to their superiors in the prefecture. He composed confidential reports for the Magister.[96] The 'princeps' reported directly to the 'magister officiorum.' He vetted all business coming in and going out of the office and countersigned all documents.[97] Staffs of the prefects and vicars could not perform tasks outside the office and no legal action instituted without his permission or order[98] The presence of an experienced bureaucrat security officer as diocesan head of office may have actually strengthened the authority of a vicar.[99] These overlapping inter-departmental controls were common practice and were part of the triad of vicar, comptrollers of the SL and RP and the 'princeps' collectively who formed a nexus of imperial authority within the diocese.[100]

The administrative overlaps and triangulations were ubiquitous in the system right down to the municipal level – checks and balances, crosschecks – and were intended to promote accountability, better performance, widen the spectrum of culpability, enforce cross-department policing (intra-departmental self-policing was not trusted as sufficient), enhance security, promote collection of information, restrict the autonomy of officials, clamp the several ministries together at three levels, and assert central control given the often great distances, slow communications and absence of sophisticated methods of data storage and retrieval.[101] A web of elaborate financial checks were designed to prevent speculation, dilatory collection and the granting of illicit rebates and remissions.[102]

Decline of the dioceses

The importance of the dioceses gradually declines with the rise of the prefectures as administrative 'power houses' in the very last decades of the 4th century. The Valentinians and Theodosius I initiated a reversal of policy in favor of centralization from the mid-360s at the palatine level, more discretionary authority for prefects to change matters such as tax demands, control exercised through high-ranking agents to deal directly with provinces: it is questionable whether these actually improved efficiency. It might have been better to have given the vicars wider powers and discretionary authority[103] However, the decline was gradual, halting, and slow in part because the central administration needed dioceses, used them to get more performance out of the governors and police the administration. At times prefects used vicars to encroach on the SL and RP by placing vicars in charge of supervising their tax collections.[104] Their range of responsibilities was not formally rescinded: they were gone around.[105] In the West, as Roman power and jurisdiction receded, all the dioceses had disappeared by 477 (when the remaining territory of the Gallic prefecture was handed over to the Visigoths), except for the vicar in Rome whose office continued to exist until the Byzantine invasion of 535 and after (probably a ceremonial sinecure since by now there was little for him to do). A "rump" prefecture with vicar was in existence in Provence 507–536 as part of the Ostrogothic Kingdom (491-536). While the dioceses survived in the East, the vicars' courts were little used and most of their fiscal responsibilities were lessened and simplified. The cumbersome mostly in-kind tax collection the vicars were responsible for was increasingly commuted to gold by 425 in the West and was largely completed by the end of the 5th in the East.[106] The change, however, did not simplify tax computation but it did made collection much easier, rendering the dioceses, which had had an important role, increasingly useless, except for some oversight functions as seen in CJ 10, 23, 3-4 of 468 by which they were instructed to make sure revenue for the SL collected by governors was not diverted to the prefecture; and which allowed the prefectures to build up large reserves of gold which had not had under the previous tax collection regime.[107] These changes specifically after 440 marked a progressive return to the pre-diocesan two-tier prefect-province governance which made dioceses increasingly redundant. Seeing their role as somewhat ineffectual, Emperor Justinian I abolished most of the dioceses in 535 and 538 as part of his great reforms of the 530s, preferring to strengthen the authority and salaries of provincial governors.[108] This practice was extended to the recovered territories of Italy and Africa (retaken in 533), where Justinian preferred to install Praetorian Prefects to directly govern the respective regions, though in the Pragmatic Sanction of 554, as a sop to members of the senatorial aristocracy seeking high honorary offices, he retained the vicar in Rome and the vicar of Italy was revived.[109] It was all swept away within twenty years after the Lombard invasion of Italy in 568. Dioceses had been created at a time of relative high security from foreign invasion and internal stability: one of its main tasks was to maintain support for the professional Roman Army and provision of other services. Wandering tribes contributed to diocesan decline and spelled the end of the imperial administrative system above the provincial level except in Italy. Without standing armies to support there was little need for the administrative supra-structure.

In the eastern parts of Roman Empire, dominated by the Greek language and common use of Greek terminology, the vicarius was titled exarch.[110]

Ecclesiastical dioceses

After Licinius and Constantine legalized the Christian religion in 313 in the so-called Edict of Milan, the churches quickly organized themselves into provinces patterned on the Roman civil administration, but they adopted the word "diocese" to describe the unit of episcopal jurisdiction equivalent to a provincial, not regional, unit as it was in the civil administration. Church dioceses were smaller than civil as there were so many more bishops than provinces. The regional ecclesiastical unit would become the archdiocese as church organization evolved. From the 5th to the 8th centuries, as the older secular administrative structure began to falter, bishops in the western lands of the former empire provided additional administration within the successor States of Germanic rulers. The senatorial aristocracy continued in many places to serve as sources of local authority to complement that assumed by the Church until it disappeared in the course of the 6th century; their position in society was linked to service in the imperial administration. After it's collapse many gravitated to the Church. The transfer of some authority from secular officials to ecclesiastical leaders was a natural consequence of the close integration of the Church and State, a doctrine known as Caesaropapism, by which emperors, kings, dukes were heads of both to varying degrees. Ecclesiastical administration and jurisdiction often coincided with the Roman civil administration until the latter disappeared.

A millennium later there was a similar process after the Ottoman Empire conquered the Eastern Roman Empire (see Christianity and Judaism in the Ottoman Empire) and the eastern bishops assumed political roles as the last remnant of the Roman civil structure was stripped away. In modern times, many ancient dioceses, though later subdivided, have preserved the boundaries of long-vanished Roman administrative divisions.

Judicial dioceses

In ancient Rome, a 'diocese' could describe the area of a judicial magistrate's jurisdiction.[111] In effect it was an assize-district. The term originated with administrative arrangements made in the then large proconsular province of Asia. This kind of diocese was a subdivision of a province and bore the name of the chief city of the area, which the governor would visit during his year of office to judge cases arising in the district (taking the assizes).[112] This subdivision already existed in the time of Cicero, who mentions three dioceses (Cibyra, Apamea, and Synnada) being added to the Province of Cilicia in a letter.[113][114] Later on, the word 'diocese' was also used in western provinces of the empire, such as Africa, where the 'diocese; was a district under the control of a legate of the Proconsul of Africa.[115] Proconsuls of the large provinces during the Principate (27 BC-284 AD) frequently appointed legates to take the Assizes on their behalf since they could not visit the entire province during their time in office. During the reign of Gallienus on occasion proconsuls were appointed directly by the emperor rather than by lot to senatorial provinces like Asia and Africa which were subject to administrative reorganization. Often these proconsuls were accompanied by 'correctores'assigned 'dioceses' larger provinces were divided into[116] These dioceses are not to be confused with the dioceses governed by vicars of praetorians prefects.

The word 'diocese' also designated the territory of a city, as the district in which municipal judges had jurisdiction. In this context, the Greek dioikesis corresponded to the Latin term regio.[117]

References

- Notitia Dignitatum circa 395

- Constantin Zuckerman, 'Sur la liste de Verone et la province de Grande Armenie, la division de l'empire et la date de création des dioceses, 2002 Travaux et Memoires 12 Mélanges Gilbert Dagron, pp. 618-637 argues for a decision to create diocese by Constantine and Licinius at the meeting in Milan in February 313; since 1980 several scholars have suggested later dates (303, 305, 306, 313/14) than the traditional date of 297 set by Mommsen in the late 19th century

- For a recent discussion, Laurent J. Cases, Historia 68, 2019/3 353-367, pp. 354-356, who reports the weight of scholarly opinion is still for 297 for which there is scant evidence "while Diocletian probably did increase the number of agentes vices praefectorum, Constantine created the vicariate in the year 313"

- David Potter suggests Constantine in expanding the number of prefects to 4 in 330 intended to recreate the Tetrarchy with prefects rather than co-emperors and their lieutenants, the Caesars, Divisio Regni 364, East and West in the Roman Empire of the Fourth Century an End to Unity, Ed. Roald Dijkstra, Sanne van Poppel, Danielles Slootjes, 'Measuring the Power of the Roman Empire,' p. 44, Radboud Studies in Humanity Vol 5. 2015

- The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine, Ed. Noel Lenski, 'Bureaucracy and Government,' Christopher Kelly, pp. 186-187, 201-202, states they were not the four fully developed prefectures the 5th-century writer Zosimus had in mind as existed in 395 - Porena opts for fully operational from 325, p. 201, footnote 15 ISBN 978-0-521-52157-4; there were three prefects in 325 - in Trier, in Italy and one with Constantine; and four in 331, five from 335-337; cf. Timothy Barnes who argues that the later Constantinian prefects are more expressions of the emperor's dynastic aims than definitively administrative in character: Constantine: Dynasty, Religion and Power in the Later Roman Empire, 2011, pp. 290-293 ISBN 978-1118782750; previously prefects were personal, i.e. attached to the office of the emperor and not territorially defined

- Laurent J. Cases, Historia 68, 2019/3, p. 360

- Pat Southern, The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine, 2001 p. 165 ISBN 0-415-23944-3; The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine, Ed. Noel Lenski, 'Bureaucracy and Government,' Christopher Kelly, pp. 185-187, 201-202 ISBN 978-0-521-52157-4

- Pat, Southern, The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine, 2001 p. 165 ISBN 0-415-23944-3; M.F. Hendy, Studies in the Byzantine Monetary Economy, 1985 300-1450, pp. 373-377, "independent ministries" until mid-5th century ISBN 978-0521088527; Jacek, Wiewiorowski The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, 2016, p. 83, "the responsibility of the vicar was to exercise control of the civilian administration in the diocese;" L.E.A. Franks, review of The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, Jacek Wiewiorowski 2016 ISBN 978-83-232-2925-4 in Byzantinische Zeitschrift 206 Vol 109 Part 2 pp. 988-994 ISBN 978-83-232-2925-4

- A.H.M. Jones, Later Roman Empire, Vol ! 1964, p, 47 "The vicars seem to have deputized for the praetorian prefects in all their manifold functions"; L.E.A. Franks, review of The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, Jacek Wiewiorowski 2016 ISBN 978-83-232-2925-4 in Byzantinische Zeitschrift 206 Vol 109 Part 2 pp. 990-991

- The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine, Ed. Noel Lenski, 'Bureaucracy and Government', Christopher Kelly, pp. 185 ISBN 978-0-521-52157-4; also for one discussion - Migl, Joachim, Die Ordnung der Amter Prätorianerpräfektur und Vikariat in der Regionsverwaltung des Römischen Reiches von Konstantin bis zur Valentinianischen Dynastie, 1994, pp. 64-68; A. Pignaniol, L'empire chretien, 1972, p. 354, "Ils ne dépendent pas des préfets du prétoire mais directement de l'empereur, et l'on fait appel de leurs décisions judiciaires à l'empereur; appeals from their verdict went straight to the emperor, Theodosian Code, 11, 30, 16 (331); but cf. in a law of 328 CTh. 11, 16, 4 addressed to Aemilianus Constantine refers to "your vicars." Prefects could not overturn the decision of vicar except on appeal; and the authority of vicars was not derivative from prefects but a share of it given to them in their own right by the emperor, CTh. 1, 15, 7, 377, "the dignity of vicar by its very name indicates that it assumes a part (of the prefecture) that it often has the power if our inquiry and is accustomed to represent the reverence of our judgment;” Cassiodorus, “Tu autem vicarius dixeris et tua privigelia non reliquia, quando propria est jurisdictio quae a principe datur. Habes enim cum praefectis aliquam portionem,” 6, 15 - Moreover the you will have been designated vicar and your prerogatives (are) not unchanged, when the jurisdiction which is given by the emperor is his own. For you have with prefects some portion

- Giardina, Andrea, Aspetti della burocrazia nel basso impero, Edizioni dell’Atneo & Bizzarri, 1977, pp. 45-93 who describes the empire-wide placement of agents in major cities as a web that connected together the administrative 'nodes' located in the larger towns and cities, p. 71; Christopher Kelly, Ruling the Later Roman Empire,2004, p. 206, 210; Jones, Later Roman Empire, 1964 pp. 103-104, 128; Kelly in Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine, pp. 188-190

- there was in addition a 'rationalis' for Sardinia and Corsica, and Sicily (although only a province - perhaps a scribal error or elevation in status, and one each for Numidia and Africa, two in the diocese of Pannonia, A.H.M. Jones, Later Roman Empire, 1964 p. 48 and from the Notitia Dignitatum circa 395 AD.; usually there were prefects in Gaul at Trier, northern half of the diocese of Italy in Milan; in the Balkans at times stationed in Serdica, Thessaloniki, or Sirmium and for Oriens at Constantinople or some other city; R. Delmaire, Les largesse sacres et res private, Latomus, 1989, pp. 171-172, 181; the RP regional managers was subordinate to the SL until sometime in the 350s during the reign of Constantius II; they always worked closely together sometimes substituting for each other, Jones op. cit. p. 1414-1416; Delmaire, p. 189; and in the West part of the RP's revenue went to the SL, Delmaire, chapter on 'Tituli Largionales;' King, C.E., Ed., Imperial Revenue, Expenditure and Monetary Policy in Fourth Century A.D., The Fifth Oxford Symposium and Monetary History, BAR International Series 76, 1980, chapters on The Res Privata by F. Millar and the SL by C. E. King

- Noel Lenski, Failure of Empire, 2002, ISBN 978-0-520-23332-4; M. Malcolm Errington, Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius, 2006, pp. 261-264' Jones, pp. 405-410

- Jacek Wiewiorowski, The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, English Edition 2016, pp. 292-293, 297 ISBN 978-83-232-2925-4;R. Malcom Errington, Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius, 200, pp. 3-4 pp. 261–262 ISBN 978-0-8078-3038-3; L.E.A. Franks, review of The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, Jacek Wiewiorowski 2016 ISBN 978-83-232-2925-4 in Byzantinische Zeitschrift 206 Vol 109 Part 2 pp. 988–994

- Jones, Later Roman, Empire; 1964, pp. 207-208, 235, 460-61; L.E.A. Franks, review of The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, Jacek Wiewiorowski 2016 ISBN 978-83-232-2925-4 in Byzantinische Zeitschrift 206 Vol 109 Part 2 p. 992

- R. Delmaire, Les largesse sacres et res private, Latomus, 1989, pp. 707-712; Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 1964, pp. 414, 434-435

- Roland Delmaire Les largitiones sacrees et res private, Latomus, 1989, pp. 703-714 ISBN 978-272-83061-38; Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284-602, pp. 280-283 ISBN 0-8018-3353-1; L.E.A. Franks, review of The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, Jacek Wiewiorowski 2016 ISBN 978-83-232-2925-4 in Byzantinische Zeitschrift 206 Vol 109 Part 2 pp. 988-994

- Jacek Wiewiorowski, The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, English Edition 2016, pp. 292-293, 297 ISBN 978-83-232-2925-4

- Jones, pp. 280-283

- Jones, pp. 294

- Jones, pp. 294

- A.H. M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284-602, 1964, pp. 404, 408-410, 280-283

- Cambridge Ancient History XII, 2001 p. 161 ISBN 978-0-521-30199-2

- Discussed in Zuckermann; Joachim Migl, Die Ordnung der Amter des Pratorianerprafaktur und Vicariat in der Regionsverwaltung des Romischen Reiches von Konstantin bis zur Valentinianischen Dynsatie, 1993. pp. 54-58; Jacek Wiewiorowski, The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, English Edition 2016, pp. 52-46 ISBN 978-83-232-2925-4; Timothy Barnes who now opts for 313/14 in Constantine: Dynasty, Religion and Power in the Later Roman Empire, 2011 pp. 177-178 and in numerous other sources from the late 19th century onwards. Wiewiorowski tabulates dates chosen by scholars in a published paper delivered in Nish in April 2013. By year: 297: Pallu de Lessert, 1899; Kornemann, 1905; Seston, 1946; Ensslin, 1958; Scheurmann, 1960; Jones, 1964; De Martino, 1967; Guademet, 1967; Arnheim, 1970; Hendy, 1972; Christol, 1977; Barnes, 1982; Chastagnol, 1985; Hendy, 1985; Sargenti, 1986; Bleckman, 1997; Carrie & Rouselle, 1999; Kuhoff, 2001; Bowman, 2005; Lo Cascio, 2005; Kulikowski, 2005; Demandt, 2007; Franks, 2012. 303: De Vita Evrard, 1985. After 306: Cuq, 1899; Potter, 2004 306-313: Porena, 2004 +312: Migl, 1994, 313/14; Noetlichs, 1982; Zuckerman, 2002; for a recent discussion, Laurent J. Cases, Historia 68, 2019/3 353-367, pp. 354-356, who reports the weight of scholarly opinion is still for 297 for which there is scant evidence "while Diocletian probably did increase the number of agentes vices praefectorum, Constantine created the vicariate in the year 313"

- Ulpian, jurist during the Severan Dynasty 192-235, “agens vices praefectorum ex mandatis principis cognoscet” and “Et is cui mandata iurisdicito est fungetur vice eius qui mandavit, non sua, Dig. II, 1, 16; “A praefectis vero praetorio vel eo, qui vice praefectis,” XXXII, 1, 4.; Cledonius 5th century grammarian in Constantinople, “Saepe quaesitum est utrum vicarius dici debeat is qui ordine codiclliorum vices agit amplissimae praefecturae; ille vero cui vices mandatur propter absentiam praefectorum, non vicarius sed vices agens; non praefecturae sed praefectorum dicitur tantum,” in Grammatici Latini. V. 13

- For an examination of these four Zuckermann

- Roland Delmaire Les largitiones sacrees et res private, Latomus, 1989, pp. 173, 181 ISBN 978-272-83061-38

- Roland Delmaire, Les largesses sacres et res private, Latomus, 1989, pp. 171-172, 181, the model is the pre-existing fiscal district of Egypt, Cyrenaica and Crete (detached in 294 and tied to Achaia)ISBN 978-272-83016-38

- R. Malcom Errington, Roman Imperial Policy from Julian to Theodosius, 200, pp. 3-4, 261-262 ISBN 978-0-8078-3038-3

- Cambridge History of the Ancient World, XII, p. p. 64

- Cambridge Ancient History XII, pp. 179-183; The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine, Ed. Noel Lenski, 'Bureaucracy and Government', Christopher Kelly, pp. 185 ISBN 978-0-521-52157-4

- Delmaire, pp. 197, 199 204-204, 245..."the power of the 'rationales' did not cease to be degraded for the 4th century after reaching the apogee of their power between 285-320. At their creation, they were omnipotent in fiscal matters of the diocese but lost it to the advantage of the governors concerning the Annona, cursus publicus and in general all that part of the fiscal (regime) entrusted to the prefects," trans. from the French, p. 204

- CAH XII, p. 377

- Diocletian's system was characterized by indiction, a published schedule of budgetary requirements within a given period and census - indiction did not take into account ability to pay, Roger Rees, Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, 2004, p. 38, ISBN 07486-1661-6, the system was distributive not contributive which is based on ability to pay; Other Means - Clyde Pharr, The Theodosian Code, 2001 12th Edition, p. 596 ISBN 978-1-58477-146-3: (re)appraise the measured assessible land and set the rates, 'censitor'; adjust inequalities and inequities in the tax assessments, 'peraequator'; inspect the taxable land to determine rates, 'inspector' who was a check on the 'censitor'; examine, revise and re-allocate rates on individual possessions,' discussor'; Jones, Later Roman Empire, p. 449; It’s amazing but until the reign of Diocletian the Empire had no global budget! This was due to the “inelastic fiscal structure of the empire which relied on fixed levies, not production, and which had not been adjusted form the foundation of the empire," Jones, p. 9; also in David, S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180-395, 2004, pp. 59, 398, also Diocletian's reforms introduced "regularity assessment was the evident effort to impose coherent units of extraction across all provinces," p. 334; “A fundamental problem of state finance had been that taxes had been cumbrously expressed in terms of fixed amounts of money, which produced inadequate income in periods of currency inflation, or as percentages, where ignorance of the sums being taxed meant that the state could not predict how much a particular tax would bring in.”— Peter Salway, The Oxford Illustrated History of Roman Britain, 1993, p. 234 ISBN 0-19-822984-4; for an excellent of description of the later imperial tax regime, Cam Grey, Constructing Communities in the Late Roman Countryside, 2011, pp. 178-197 ISBN 978-1-107-01162-5

- for discussion of the range of Diocletian's reforms -Jones, The Later Roman Empire. Vol. I, pp. 42-50, 101-102, 449 ; The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine, Ed. Noel Lenski, 'Bureaucracy and Government,' Christopher Kelly, pp. 183-92 ISBN 978-0-521-52157-4; David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay 180-395, 2004, pp. 367-377 ISBN 0-415-10058-5; Pat Southern, The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine, 2001 pp. 153-167 ISBN 0-415-23944-3; Roger Rees, Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, 2004, ISBN 0-7486-1661-6; M.F. Hendy, Studies in the Byzantine Monetary Economy, 1985 300-1450, pp. 373-377 ISBN 978-0521088527

- CAH XII. p. 123

- Pat Southern, p. 165

- Jones, p. 373

- the rise of the prefectures as administrative dates from the Valentinian Dynasty post-364 esp. the build-up of Constantinople as the seat of government in the East beginning under Valens, 364-378, even though he spent almost no time there, and which was finally achieved by Theodosius I, 379-395, Errington, p. 262

- Peter Heather, CAH XIII, pp. 189-190, 209; Peter Kelly, Ruling the Later Roman Empire, p. 69

- Kelly. pp. 187-191

- Jones, p. 371, "grand vizier;" Kelly, pp. 186; David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay 180-395, 2004, pp. 367-377 ISBN 0-415-10058-5; Pat Southern, The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine, 2001 pp. 153-167 ISBN 0-415-23944-3

- Pat Southern & Karen R. Dixon, The Late Roman Army, 1996, pp. 63-64

- Javier Arce, El Ultimo Siglo de la Espana Roman, 284-409, second edition 2009, p. 74 ISBN 978-84-206-8266-2

- CAH, pp. 284-286, 319 in another theory it was not a special tax but part of the normal tax earmarked for the army p. 381 overseen by vicars p. 181; Pat Southern and Karen R. Dixon, The Late Roman Army, 1996, pp. 62-63 ISBN 0-300-06843-3; Cam Grey, Constructing Communities in the Late Roman Countryside, 20111, pp. 178-197 ISBN 978-1-107-01162-5 the Annona Militaris is one example of a change from ad hoc and arbitrary to fixed, permanent charges within total budgetary process in the modern sense and, for which, vicars were responsible in their dioceses

- Delmaire, p. 703-704

- Kelly, pp. 186-190

- The Cambridge Ancient History XII, 2001, pp. 170-183, 'The new state of Diocletian and Constantine from the Tetrarchy to the reunification of the empire'ISBN 978-0-521-30199-2; Jones, The Later Roman Empire. Vol. I, pp. 42-50, 101-102, 449 ISBN 0-8018-3353-1; The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine, Ed. Noel Lenski, 'Bureaucracy and Government,' Christopher Kelly, pp. 183-192 ISBN 978-0-521-52157-4; David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay 180-395, 2004, pp. 367-377

- Kelly, pp. 186-187

- David Potter suggests Constantine in expanding the number of prefects to 4 in 330 intended to recreate the Tetrarchy with prefects rather than co-emperors and their lieutenants, the Caesars, Divisio Regni 364, East and West in the Roman Empire of the Fourth Century an End to Unity, Ed. Roald Dijkstra, Sanne van Poppel, Danielles Slootjes, 'Measuring the Power of the Roman Empire,' p. 44, Radboud Studies inhumanity Vol 5. 2015; cf. Timothy Barnes who argues that the later Constantinian prefects are more expressions of the emperor's dynastic aims than definitively administrative in character: Constantine: Dynasty, Religion and Power in the Later Roman Empire, 2011, pp. 290-293 ISBN 978-1118782750; previously prefects were personal, i.e. attached to the office of the emperor and not territorially defined

- Codex Theodosianus 1, 15, 7 (377) shared, not derived from prefects, “vicaria dignitas ipso nomine se trahere indicet portionem et saepe cognitionis habeat potestatem et iudicationis nostrae soleat repraesentare reverentiam,” CTh. 1, 15, 7 (377), "the dignity of vicar by its very name indicates that it assumes a part (of the prefecture) that it often has the power if our inquiry and is accustomed to represent the reverence of our judgment;” Cassiodorus, “Tu autem vicarius dixeris et tua privigelia non reliquia, quando propria est jurisdictio quae a principe datur. Habes enim cum praefectis aliquam portionem,” 6, 15 - Moreover the you will have been designated vicar and your prerogatives (are) not unchanged, when the jurisdiction which is given by the emperor is his own. For you have with prefects some portion

- CAH XII pp. 181-182; Roland Delmaire Les largitiones sacrees et res private, Latomus, 1989, pp. 173, 181, 202-205, 245 ISBN 978-272-83061-38; L.E.A. Franks, review of The Judiciary of Diocesan Vicars in the Later Roman Empire, Jacek Wiewiorowski 2016 ISBN 978-83-232-2925-4 in Byzantinische Zeitschrift 206 Vol 109 Part 2 pp. 988-994; Jones, LRE pp. 101--102, 414, 434, 448-451- 485-486; M.F. Hendy, Studies in the Byzantine Monetary Economy, 300-1450 A.d., 1985 pp. 373-377 ISBN 978-0521088527; from the early 340s inspection of the State Post was placed with master of the offices; maintenance remained with the prefecture; and costs paid for by provincials along the routes

- Delamire,197, 204-206, 245

- introduction of the procurators by Diocletian, CAH XII, p. 76; Delmaire, disbandment of procurators, p. 206-209 and SL comptroller duties post-325/330 204-205

- Jones, pp. 485-486, 1207; Franks, p. 992; CTh. 11, 16, 28 of 359 mentions the transference by Constantine which can tracked to 327–329 by reference to laws 14 and 18

- CAH XII p. 380

- the exceptions were Egypt, which did not have its own vicar till 370 or 380, and in the West according to the Notitia Dignitatum of circa 395, there were 6 vicars, 2 prefects governing dioceses, but 11 comptrollers (two in Africa, two in Pannonia, and one for the Island of Sicilia, Sardinia and Corsica Notitia Dignitatum; Franks, pp. 990-992

- Delmaire, op. cit. p 39 from CIL II, 4107 or by 344 at the latest CTh. 8, 2, 10. The heads of the SL and RP were made 'comites' the same year; and Prefect of the Annona of Rome senator also in 326 from Chastognol cited by Rickman, The Corn Supply of Rome, 1980 p. 200, dated the elevation of the prefectus annonae of Rome to senator to the year 326

- Jones, pp. 486, 1207

- "The Largitiones issued 'dispositiones' (administrative regulations, timetables, schedules), 'mandata' (standard instructions, orders issued to officials) and 'commonitoria' (orders, memoranda) Delmaire p. 68

- Jones, pp. 487-488

- Southern and Dixon, The Late Roman Army, 1996, pp. 62-63, ISBN 0-300-06843-3; R. Mitthof, Annona Militaris: Die Heeresversorgung im spätantiken Aeygpten, (Papyrologica Fiorentiana 32) 2001, pp. 273-286. Mithoff states that civilian control was for security purposes but it was inefficient as it relied on reluctant local officials and liturgists to collect and distribute massive quantities of supplies which could have been more efficiently bought on the open market as required; Justinian reverted to direct purchase. The lack of gold in circulation until the end of the 4th century hindered the transition, Delmaire, pp. 709-712; Jones 207-208, 235, 460-461

- Kelly, p. 189

- CAH XII, p. 380

- Franks, p. 991-992

- Jones. p. 450

- Franks, p. 992

- Joachim Migl, Die Ordnung der Amter des Pratorianerprafaktur und Vicariat in der Regionsverwaltung des Romischen Reiches von Konstantin bis zur Valentinianischen Dynsatie, 1993. pp. 54-58; Franks, pp. 992-993

- R. Malcolm Errington, 2006, p. 261-262, ISBN 978-0-8078-3038-3

- Delmaire, pp. 709-711; Jones, pp. 485-486; Franks, p. 992; the laws allowing appeals once again to the counts of the SL and RP with the emperors CTh. 11, 35, 45 = CJ 7, 62 26 to the RP and 46 to the SL both of year 385

- The picture is one of occasional interventions from and a permanent awareness of the higher levels of provincial government; the whole bureaucratic machinery seems to have been intended to maximize revenues and channel these according to government policies; including a system of checks and measures to insure accountability, Roger Rees, Diocletian and the Tetrarchy, 2004, p. 35 ISBN 0-7486-1661-6; speaking of Egypt, "The imperial administration was therefore present above all in those cities in which the governors had their seats," Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300- 700 AD, Ed. Roger Bagnall, 2007, 'The Imperial Presence: Government and army, pp. 249-251 ISBN 978-0521-14587-9, 4 cities in a crowded land, 2,000 officials total for 4.75 million inhabitants

- Jones, p. 281; Codex Theodosianus 11, 30, 16 (331)

- CTh. 11, 30. 16 (331))If the litigant won his appeal with the prefect the vicar could be fined for having refused the appeal

- cf. Relationes of Symmachus, urban prefect of Rome 382-384, who passed on cases to get them off his hands, Barrow, R.H., Prefect and Emperor, The Relationes of Symmachus, A.D. 384, Oxford University Press, 1973 Barrow, The Relationes of Symmachus; Jones, pp. 490-491; Wiewiorowski, pp. 291-292

- CTh. 11, 30 16, 331)

- Jones, pp. 493-496

- (in the southern part of the Diocese of Italy where the Urban Prefect of Rome also had this authority; from 361 the urban prefect of Constantinople had appellate authority in 9 adjacent provinces in the dioceses of Thrace, Pontus and Asia to match the dignity of the prefect in 'Old' Rome, and of course the praetorian prefect of the East); proconsuls were iudices ordinarii judges of the first instance and vice sacra iudicantes, appellate judges in their own provinces, Jones, p. 481-482; the four prefects of the Annona did not have appellate jurisdiction - if something went amiss cases went to a prefect or vicar, for a complicated multi-jurisdictional case headed by the vicar in Africa CTh. 11, 1, 13 (366)

- CAH XII p. 181

- Franks, pp. 990-991; 'munera' is the plural of 'munus', which in effect was a type of tax; see CTh. 1, 12, 2 (319) of the proconsul of Africa's financial oversight duties which were identical to those of the vicar of Africa

- the prefects used the latter in preference from the mid-5th century to communicate directly with their provincial permanent counterparts and ad hoc deputies in the provinces thus bypassing the diocesan department heads, the 'curae epistolarum,' one sign of diocesan decline, Jones, pp. 281

- J. F. Haldon, Byzantium in the Seventh Century, 1990 pp. 188-189 ISBN 0-521-31917-X who cites Jones pp. 428-429 for the operation of the SL depots

- Southern and Dixon, The Late Roman Army, 1996, pp. 62-63, ISBN 0-300-06843-3; Jones, pp. 623-630; R. Mitthof, Annona Militaris: Die Heeresversorgung im spätantiken Aeygpten, (Papyrologica Fiorentiana 32) 2001, pp. 273-286

- Jones, p. 606

- "…the Comes Orientis had special powers and duties in connection with military matters (probably concerning the organization of supplies and the quartering of troops),” Downey, Glanville, A History of Antioch in Syria, 1963, p. 355. The last comes orientis 335-337 was making preparations for Constantine's invasion of Persian when the emperor died; also the vicar of Britain, the Augustal Prefect (vicar) of Egypt and the vicars of Pannonia and Dacia had important defense responsibilities;

- Codex Theodosianus 1, 15, 13 and 1, 12, 1)

- A.H.M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 1964 pp. 374, 450, 496, "the vicars seem to have deputized for the praetorian prefects in all their manifold functions,' p. 47; Stephen Williams, Diocletian and the Roman Recovery, 1985, p. 110, "The prefect had ultimate responsibility ...for the whole apparatus of civil administration, including taxation...he was now able to delegate much of the detailed work to the 12 vicars with their attached fiscal departments" ISBN 0-416-01151-9

- Jones, LRE, 1964, pp. 724-766

- Kelly, pp. 190-194, 204-212

- Two sources in the 5th century indicate their number 1174 and 1248 in the East, Jones, p. 578

- Jones, p. 128

- Palme, Bernhard, ‘Die Officia der Statthalter in der Spatantike,’ Antiquite Tardive, 7, 1999, pp. 108-110

- CTh. 6. 27. 8 435

- The Age of Constantine, Kelly, pp. 187-190

- Giardina, Andrea, Aspetti della burocrazia nel basso impero, Edizioni dell’Atneo & Bizzarri, 1977, pp. 45-93, “the agentes in rebus were part of a widespread system of control. There were various sectors of the government which they operated in as guarantees of political security. These sectors covered all vital nerve tissue bundles (“ganglia”) (or focuses of strength metaphorically) of the State, from the lines of communication to imperial defense factories, from the transmission of messages to the command of the civil service bureaux, to prevent rebellion, to control the administration and apply the laws: there were sore points for the late ancient State, and for this reason, these were subjects of great concern to the central government and, what’s more, if one thinks about it, the reason for the very frequent orders concerning the collective responsibility of government departments. The presence of agentes in rebus, who through long familiarity with administrative functioning, were experts in jobs of varying responsibilities must have guaranteed the efficient carrying out of technical work, administrative surveillance and political control,“ p. 71

- Jones, p. 128

- Jones, p. 128; A. Piganiol, L’empire chretien (325-395), 1947, p. 321 “lui-meme ne depend pas des prefets du pretoire, mais directemente du prince; le prefet ne peut intercepter ses rapports, et c’est au prince, non pas au prefets, qu’on fait appel des decisions judicaires du vicaire,” p. 354.

- Codex Theodosianus 6, 28 4 (387 = Codex Justinianus 12, 21, 1); Sinnigen, William G. 'Three Administrative Changes attributed to Constantius II', American Journal of Philology, 83, 1962, pp. 369-383

- CTh. 6, 27, 1 (379); 4 (387) = CJ 12, 21 1; 6 (399); 8 (435) =CJ 12, 21, 4

- Kelly pp. 188-191; Jones, p. 128; Sinnigen, 369-383

- Franks, p. 991

- Kelly, Ruling the Later Empire, 2004, pp. 190, 204-212 ISBN 0-674-01564-9

- Jones, p. 409

- A.H. M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284-602, 1964, pp. 404, 408-410, 280-283

- Jones, p. 414; Delmaire, pp. 703-714; Errington, pp. 261-265; Franks, pp. 992-993; Wiewiorowski, pp. 297, 299

- Wiewiorowski, p. 299

- Jones, p. 461

- Jones. p. 461

- Jones, LRE pp. 280-283; Delmaire, Introduction IX-XI, pp. 710-712; Wiewiorowski, pp. 293, 297; Franks p. 993

- Jones, p. 292

- Meyendorff 1989.

- Ch. Daremberg & Edm. Saglio, Dictionnaire des Antiquités grecques et romaines, vol. 2, ed. Hachette, Paris, 1877-1919, p. 226, online.

- Daremberg, p. 226

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 354.

- Cicero, Ad familiares, 13.67.1.

- Daremberg et al. (vol. 2), p. 226

- CAH, p. 161

- Daremberg

Sources

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450-680 A.D. The Church in history. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)