Raqqa

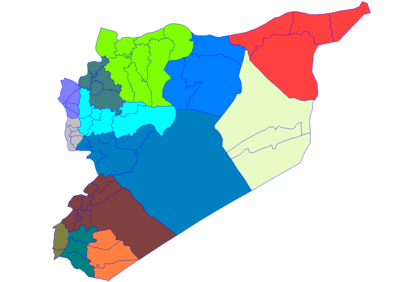

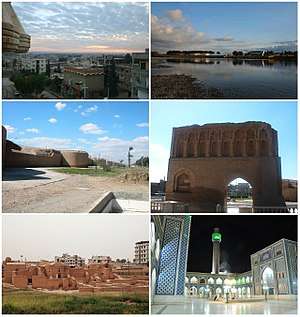

Raqqa (Arabic: الرَّقة ar-Raqqah), also called Raqa, Rakka and ar-Raqqah, is a city in Syria on the northeast bank of the Euphrates River, about 160 kilometres (99 miles) east of Aleppo. It is located 40 kilometres (25 miles) east of the Tabqa Dam, Syria's largest dam. The Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine city and bishopric Callinicum (formerly a Latin and now a Maronite Catholic titular see) was the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate between 796 and 809, under the reign of Harun al-Rashid. It was also the capital of the Islamic State from 2014 to 2017. With a population of 220,488 based on the 2004 official census, Raqqa is the sixth largest city in Syria.[2]

Raqqa الرقة Reqa | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

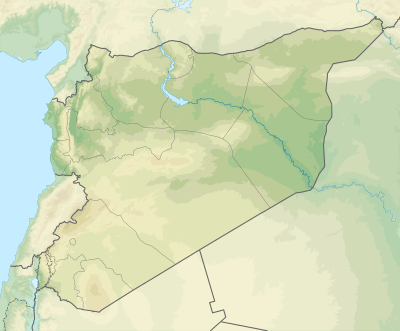

Raqqa Location of Raqqa within Syria | |

| Coordinates: 35°57′00″N 39°01′00″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Raqqa |

| District | Raqqa |

| Founded | 244–242 BC |

| Area | |

| • City | 35 km2 (14 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 245 m (804 ft) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • City | 300,000[1] |

| • Pre-Civil War | City: 220,488, Nahiyah: 338,773[2] |

| Demonym(s) | Arabic: رقاوي, romanized: Raqqawi |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| P-Code | C5710 |

| Area code(s) | 22 |

| Geocode | SY110100 |

During the Syrian Civil War, the city was captured in 2013 by the Syrian opposition and then by the Islamic State. ISIL made the city its capital in 2014.[3] As a result, the city was hit by airstrikes from the Syrian government, Russia, the United States, and several other countries. Most non-Sunni religious structures in the city were destroyed by ISIL, most notably the Shia Uwais al-Qarni Mosque, while others were converted into Sunni mosques. On 17 October 2017, following a lengthy battle that saw massive destruction to the city, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) declared the liberation of Raqqa from the Islamic State to be complete.[4]

History

Hellenistic and Byzantine Kallinikos

The area of Raqqa has been inhabited since remote antiquity, as attested by the mounds (tells) of Tall Zaydan and Tall al-Bi'a, the latter being identified with the Babylonian city Tuttul.[5]

The modern city traces its history to the Hellenistic period, with the foundation of the city of Nikephorion (Ancient Greek: Νικηφόριον, Latinized as Nicephorion or Nicephorium) by Seleucid King Seleucus I Nicator (reigned 301–281 BC). His successor, Seleucus II Callinicus (r. 246–225 BC), enlarged the city and renamed it after himself as Kallinikos (Καλλίνικος, Latinized as Callinicum).[5] Isidore of Charax, in the Parthian Stations, writes that it was a Greek city, founded by Alexander the Great.[6][7]

In Roman times, it was part of the Roman province of Osrhoene but had declined by the fourth century. Rebuilt by Byzantine Emperor Leo I (r. 457–474 AD) in 466, it was named Leontopolis (in Greek Λεοντόπολις or "city of Leon") after him, but the name Kallinikos prevailed.[8] The city played an important role in the Byzantine Empire's relations with Sassanid Persia and the wars fought between the two empires. By treaty, the city was recognized as one of the few official cross-border trading posts between the two empires, along with Nisibis and Artaxata.

The town was near the site of a battle in 531 between Romans and Sasanians, when the latter tried to invade the Roman territories, surprisingly via arid regions in Syria, to turn the tide of the Iberian War. The Persians won the battle, but the casualties on both sides were high. In 542, the city was destroyed by the Persian Emperor Khusrau I (r. 531–579), who razed its fortifications and deported its population to Persia, but it was subsequently rebuilt by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565). In 580, during another war with Persia, the future Emperor Maurice scored a victory over the Persians near the city during his retreat from an abortive expedition to capture Ctesiphon.[8]

Early Islamic period

In the year 639 or 640, the city fell to the Muslim conqueror Iyad ibn Ghanm. Since then, it has figured in Arabic sources as al-Raqqah.[5] At the surrender of the city, the Christian inhabitants concluded a treaty with Ibn Ghanm that is quoted by al-Baladhuri. The treaty allowed them freedom of worship in their existing churches but forbade the construction of new ones. The city retained an active Christian community well into the Middle Ages (Michael the Syrian records 20 Syriac Orthodox (Jacobite) bishops from the 8th to the 12th centuries[9]), and it had at least four monasteries, of which the Saint Zaccheus Monastery remained the most prominent one.[5] The city's Jewish community also survived until at least the 12th century, when the traveller Benjamin of Tudela visited it and attended its synagogue.[5]

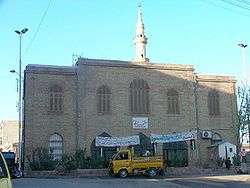

Ibn Ghanm's successor as governor of Raqqa and the Jazira, Sa'id ibn Amir ibn Hidhyam, built the city's first mosque. The building was later enlarged to monumental proportions, measuring some 73 by 108 metres (240 by 354 feet), with a square brick minaret added later, possibly in the mid-10th century. The mosque survived until the early 20th century, being described by the German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld in 1907, but has since vanished.[5] Many companions of Muhammad lived in Raqqa.

In 656, during the First Fitna, the Battle of Siffin, the decisive clash between Ali and the Umayyad Mu'awiya took place about 45 kilometres (28 mi) west of Raqqa. The tombs of several of Ali's followers (such as Ammar ibn Yasir and Uwais al-Qarani) are in Raqqa and have become sites of pilgrimage.[5] The city also contained a column with Ali's autograph, but it was removed in the 12th century and taken to Aleppo's Ghawth Mosque.[5]

The strategic importance of Raqqa grew during the wars at the end of the Umayyad Caliphate and the beginning of the Abbasid Caliphate. Raqqa lay on the crossroads between Syria and Iraq and the road between Damascus, Palmyra and the temporary seat of the caliphate Resafa, al-Ruha'.

Between 771 and 772, the Abbasid caliph al-Mansur built a garrison city about 200 metres (660 feet) to the west of Raqqa for a detachment of his Khorasanian Persian army. It was named al-Rāfiqah, "the companion", whose city wall is still visible.

Raqqa and al-Rāfiqah merged into one urban complex, together larger than the former Umayyad capital, Damascus. In 796, the caliph Harun al-Rashid chose Raqqa/al-Rafiqah as his imperial residence. For about 13 years, Raqqa was the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, which stretched from Northern Africa to Central Asia, but the main administrative body remained in Baghdad. The palace area of Raqqa covered an area of about 10 square kilometres (3.9 sq mi) north of the twin cities. One of the founding fathers of the Hanafi school of law, Muḥammad ash-Shaibānī, was chief qadi (judge) in Raqqa. The splendour of the court in Raqqa is documented in several poems, collected by Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahāni in his "Book of Songs" (Kitāb al-Aghāni). Only the small, restored so-called Eastern Palace at the fringes of the palace district gives an impression of Abbasid architecture. Some of the palace complexes dating to the period have been excavated by a German team on behalf of the Director General of Antiquities. There was also a thriving industrial complex located between the twin cities. Both German and English teams have excavated parts of the industrial complex, revealing comprehensive evidence for pottery and glass production. Apart from large dumps of debris, the evidence consisted of pottery and glass workshops, containing the remains of pottery kilns and glass furnaces.[10]

Approximately 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) west of Raqqa lay the unfinished victory monument Heraqla from the time of Harun al-Rashid. It is said to commemorate the conquest of the Byzantine city of Herakleia in Asia Minor in 806. Other theories connect it with cosmological events. The monument is preserved in a substructure of a square building in the centre of a circular walled enclosure, 500 metres (1,600 ft) in diameter. However, the upper part was never finished because of the sudden death of Harun al-Rashid in Greater Khorasan.

After the return of the court to Baghdad in 809, Raqqa remained the capital of the western part of the Abassid Caliphate.

Decline and period of Bedouin domination

Raqqa's fortunes declined in the late 9th century because of continuous warfare between the Abbasids and the Tulunids, and then with the Shia movement of the Qarmatians. Under the Hamdānids in the 940s, the city declined rapidly. From the late 10th century to the early 12th century, Raqqa was controlled by Bedouin dynasties. The Banu Numayr had their pasture in the Diyār Muḍar, and the Banu Uqay had their centre in Qal'at Ja'bar.

Second blossoming

Raqqa experienced a second blossoming, based on agriculture and industrial production, during the Zangid and Ayyubid dynasties during the 12th and the former half of the 13th century. Most famous is the blue-glazed so-called Raqqa ware. The still-visible Bāb Baghdād (Baghdad Gate) and the so-called Qasr al-Banāt (Castle of the Ladies) are notable buildings of the period. The famous ruler 'Imād ad-Dīn Zangī, who was killed in 1146, was initially buried in Raqqa, which was destroyed during the 1260s Mongol invasions of the Levant. There is a report on the killing of the last inhabitants of the urban ruin in 1288.

Ottoman period

In the 16th century, Raqqa again entered the historical record as an Ottoman customs post on the Euphrates. The eyalet (province) of Raqqa (in Ottoman form sometimes spelled as Rakka) was created. However, the capital of the eyalet and seat of the vali was not Raqqa but Al-Ruha', which is about 160 kilometres (99 mi) north of Raqqa.

from the 1820s, Raqqa was a place of wintering for the semi-nomadic Arab 'Afadla tribal confederation and was practically an empty place that presented only its extensive archeological remains. It was the establishment in 1864 by the Ottomans of a Janissary garrison 'Karakul' in the south-east corner of the Abbasid enclosure, that led to the revival of the modern city of Raqqa.[11] It attracted many families from Iraq, other parts of Syria and southeastern Turkey. Over the following decades, the province became the centre of the Ottoman Empire's tribal settlement (iskân) policy.[12]

The first families that settled in Raqqa were nicknamed ''The Ghul'' by the surrounding Arab semi-nomadic tribes from which they bought the right to settle within the Abbasid enclosure, near the Ottoman garrison. They recovered the ancient bricks of the enclosure to build the first buildings of modern Raqqa. They came under the protection of the surrounding Arab semi-nomadic tribes because they feared attacks from other neighboring tribes on their herds.[11] As a result, these families decided to form an alliance of two gatherings. one of them was called "Al-Akrad", which means "the Kurds" in Arabic. This gathering included Kurds but also Arabs and perhaps Turks as well. Even today there is still a controversy about the fact that some families in the Al-Akrad gathering refuse the Kurdish designation. The Akrad say that they mostly belong to the Mîlan tribe and the Dulaym tribe. Which might explain some of the controversy within the gathering due to the Mîlan tribe being mostly Kurdish and the Dulaym tribe being Arabs. Most of the Kurdish families in this gathering came from an area called ''Nahid Al-Jilab'', which is 20 kilometres (12 miles) northeast of Şanliurfa.[11] Prior to the Syrian Civil War, there were many families that still belonged to the Kurdish Mîlan tribe such as Khalaf Al-Qasim, Al-Jado, Al-Hani and Al-Shawakh.[13] They claimed the area west of Ottoman garrison.[11]

The Kurds of the Mîlan tribe have been present in Raqqa since 1711. The Ottomans issued an order to deport them from the Nahid Al-Jilab region to the Raqqa area. However most of the tribe was returned to their original home as a result of diseases among their cattle and frequents deaths due to the inappropriate weather in the region of Raqqa. In the med-18th century the Ottomans recognised Kurdish tribal chiefs and appointed the Kurdish chief ''Mahmud Kalash Abdi'' as head of iskân policy in the region. The tribal chiefs had the power to impose taxes and control over other tribes in the region.[13]

Some of the Kurdish families were displaced to the northern countryside of Raqqa as a result of imposed tax by force by the Arab 'Annazah tribe, after they had co-operated with French forces against the Kurds[13]

The other gathering ''Asharin'', hailed from the town of Al-Asharah, located on the southern banks of the Euphrates. The gathering included several Arab tribes and they say that they belongs to the Al-Bu Badran and Mawali tribes. The claimed the area east of the Ottoman garrison.[11]

20th century

In the early 20th century, two waves of Cherkess refugees from the Caucasian War were granted lands west of the Abbasid enclosure by the Ottomans.[11]

In 1915, Armenians fleeing the Armenian Genocide were also collected in Raqqa by the Arab Ujayli family. Most of them returned to Aleppo in the 1920s, but they have since then formed the majority of Raqqa's Christian community.[11]

In the 1950s, the worldwide cotton boom stimulated an unprecedented growth of the city and the recultivation of this part of the middle Euphrates area. Cotton is still the main agricultural product of the region.

The growth of the city meant, on the other hand, the removal of the archaeological remains of the city's past. The palace area is now almost covered with settlements as well as the former area of the ancient al-Raqqa (today Mishlab) and the former Abbasid industrial district (today al-Mukhtalţa). Only parts were archaeologically explored. The 12th-century citadel was removed in the 1950s (today Dawwār as-Sā'a, the clock-tower circle). In the 1980s, rescue excavations in the palace area began as well as the conservation of the Abbasid city walls with the Bāb Baghdād and the two main monuments intra muros, the Abbasid mosque and the Qasr al-Banāt.

There is a museum, known as the Raqqa Museum, housed in an administration building that was erected during the French Mandate.

Syrian Civil War and ISIL

In March 2013, during the Syrian Civil War, Islamist jihadist militants from Al-Nusra Front and other groups (including the Free Syrian Army[3]) overran the government loyalists in the city during the Battle of Raqqa and declared it under their control after they had taken the central square and pulled down the statue of the former president of Syria, Hafez al-Assad.[14]

The Al Qaeda-affiliated Al-Nusra Front set up a sharia court at the sports centre[15] and in early June 2013, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant said that it was open to receive complaints at its Raqqa headquarters.[16]

Migrations

Migration from Aleppo, Homs, Idlib and other inhabited places to the city occurred as a result of the ongoing civil war in the country, and Raqqa was known as the hotel of the revolution by some because of the number of people who moved there.[3]

Control by the Islamic State (January 2014–October 2017)

ISIL took complete control of Raqqa by 13 January 2014.[17] ISIL proceeded to execute Alawites and suspected supporters of Bashar al-Assad in the city and destroyed the city's Shia mosques and Christian churches[18] such as the Armenian Catholic Church of the Martyrs, which was then converted into an ISIL police headquarters and an Islamic centre, tasked to recruit new fighters.[19][20][21] The Christian population of Raqqa, which had been estimated to be as much as 10% of the total population before the civil war began, largely fled the city.[22][23][24]

On 15 November 2015, France, in response to attacks in Paris two days earlier, dropped about 20 bombs on multiple ISIL targets in Raqqa.[25]

Pro-government sources said that an anti-IS uprising took place between 5 and 7 March 2016.[26]

On 26 October 2016, US Defense Secretary Ash Carter said that an offensive to take Raqqa from IS would begin within weeks.[27]

The SDF, supported by the US, launched the Second Battle of Raqqa on 6 June 2017 and declared victory in the city on 17 October 2017. Bombardment by the US-led coalition led to destruction of most of the city, including civilian infrastructure.[28][29][30][4] Some 270,000 people were said to have fled Raqqa with no homes to which to return.[31]

Aftermath

At the end of October 2017, the government of Syria issued a statement that said: "Syria considers the claims of the United States and its so-called alliance about the liberation of Raqqa city from ISIS to be lies aiming to divert international public opinion from the crimes committed by this alliance in Raqqa province.... more than 90% of Raqqa city has been leveled due to the deliberate and barbaric bombardment of the city and the towns near it by the alliance, which also destroyed all services and infrastructures and forced tens of thousands of locals to leave the city and become refugees. Syria still considers Raqqa to be an occupied city, and it can only be considered liberated when the Syrian Arab Army enters it".[32]

Control by Syrian Democratic Forces (October 2017–present)

By June 2019, 300,000 residents had returned to the city, including 90,000 IDPs, and many shops in the city have reopened.[1] By the efforts of the Global Coalition and the Raqqa Civil Council, several public hospitals and schools have been reopened, public buildings like the stadium, the Raqqa Museum, mosques and parks have been restored, anti-extremism educational centers for youth have been established and the rebuilding and restoration of roads, roundabouts and bridges, installation of solar-powered street lighting, water restoration, demining, re-institution of public transportation and rubble removal has taken place.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44]

However, the Global Coalition's funding of the stabilization of the region has been limited, and the Coalition has stated that any large scale aid will be halted until a peace agreement for the future of Syria through the Geneva process has been reached. Rebuilding of residential houses and commercial buildings has been placed solely in the hands of civilians, there is a continued presence of rubble, unreliable electricity and water access in some areas, schools still lacking basic services and the presence of ISIL sleeper cells and IEDs. Some sporadic protests against the SDF have taken place in the city in the summer of 2018.[45][46][47][48][49]

On 7 February 2019, the SDF media center announced the capture of 63 ISIL operatives in the city. According to the SDF, the operatives were a part of a sleeper cell and were all arrested within a 24-hour time span, ending the day-long curfew that was imposed on the city the day before.[50]

In mid-February 2019, a mass grave holding an estimated 3,500 bodies was discovered below a plot of farmland in the Al-Fukheikha agricultural suburb. It was the largest mass grave discovered post-ISIL rule thus far. The bodies were reported to be the victims of executions when ISIL ruled the city.[51]

In 2019 a project called the "Shelter Project" was launched by international organisations in coordination with the Raqqa Civil Council, providing funding to residents of partially destroyed buildings in order to aid with their reconstruction.[52] In April 2019 the rehabilitation of the Old Raqqa Bridge over the Euphrates was finished. The bridge was originally built by British forces during World War Two in 1942.[53] The National Hospital in Raqqa was reopened after rehabilitation work in May 2019.[54]

As a consequence of the 2019 Turkish offensive into north-eastern Syria, the SDF called on the Syrian Arab Army to enter the areas under its rule, including in the area of Raqqa as part of a deal to prevent Turkish troops from capturing any more territory in northern Syria.[55][56]

Scanning for Syria project (2017–2018)

The Raqqa Museum had numerous clay tablets with cuneiform writing and many other objects vanishing in the fog of war. A particular set of those tablets were excavated by archaeologists from Leiden at the Tell Sabi Abyad. The excavation team casted silicone rubber moulds of the tablets before the war to create cast copies for subsequent studies in the Netherlands. As the original tablets were looted, those moulds became the only evidence of parts of the 12th century BC in Northern Syria. Having a lifespan of roughly thirty years, the moulds proved not be a durable solution, hence the need for digitization to counter the loss of the originals. Therefore the Scanning for Syria (SfS) project[57] was initiated by the Leiden University and Delft University of Technology under the auspices of the Leiden-Delft-Erasmus Centre for Global Heritage and Development.[58] The project received a NWO–KIEM Creatieve Industrie grant to use of 3D acquisition and 3D printing technology to make high quality reproductions of the clay tablets.[59] In collaboration with the Catholic University of Louvain and the Heidelberg University several imaging technologies were explored to find the best solution to capture the precious texts hidden within the concavities of the moulds. In the end, the X-ray micro-CT scanner housed at the TU Delft laboratory of Geoscience and Engineering turned out to be a good compromise between time-efficiency, accuracy and text recovery. Accurate digital 3D reconstructions of the original clay tablets were created using the CT data of the silicon moulds.[60] Furthermore, the Forensic Computational Geometry Laboratory in Heidelberg dramatically decreased the time for decipherment of a tablet by automatically computing high quality images using the GigaMesh Software Framework. These images clearly show the cuneiform characters in publication quality, which otherwise would have taken many hours to manually craft a matching drawing.[61] The 3D-models and high-quality images have become accessible to both scholar and non-scholar communities worldwide. Physical replicas were produced using 3D-printing. The 3D-prints serve as teaching material in Assyriology classes as well as for visitors of the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden to experience the ingenuity of Assyrian cuneiform writing. In 2020 the SfS has received the European Union Prize for Cultural Heritage of the Europa Nostra in the category research.[62]

Ecclesiastical history

In the 6th century, Kallinikos became a center of Assyrian monasticism. Dayra d'Mār Zakkā, or the Saint Zacchaeus monastery, situated on Tall al-Bi'a, became renowned. A mosaic inscription there is dated to the year 509, presumably from the period of the foundation of the monastery. Daira d'Mār Zakkā is mentioned by various sources up to the 10th century. The second important monastery in the area was the Bīzūnā monastery or Dairā d-Esţunā, the 'monastery of the column'. The city became one of the main cities of the historical Diyār Muḍar, the western part of the Jazīra.

Michael the Syrian records twenty Syriac Orthodox (Jacobite) bishops from the 8th to the 12th centuries[9]—and had at least four monasteries, of which the Saint Zaccheus Monastery remained the most prominent.

In the 9th century, when Raqqa served as capital of the western half of the Abbasid Caliphate, Dayra d'Mār Zakkā, or the Saint Zacchaeus Monastery, became the seat of the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch, one of several rivals for the apostolic succession of the Ancient patriarchal see, which has several more rivals of Catholic and Orthodox churches.

Bishopric

Callinicum early became the seat of a Christian diocese. In 388, Byzantine Emperor Theodosius the Great was informed that a crowd of Christians, led by their bishop, had destroyed the synagogue. He ordered the synagogue rebuilt at the expense of the bishop. Ambrose wrote to Theodosius, pointing out he was thereby "exposing the bishop to the danger of either acting against the truth or of death",[63] and Theodosius rescinded his decree.[64]

Bishop Damianus of Callinicum took part in the Council of Chalcedon in 451 and in 458 was a signatory of the letter that the bishops of the province wrote to Emperor Leo I the Thracian after the death of Proterius of Alexandria. In 518 Paulus was deposed for having joined the anti-Chalcedonian Severus of Antioch. Callinicum had a Bishop Ioannes in the mid-6th century.[65][66] In the same century, a Notitia Episcopatuum lists the diocese as a suffragan of Edessa, the capital and metropolitan see of Osrhoene.[67]

Titular sees

No longer a residential bishopric, Callinicum has been listed by the Catholic Church twice as a titular see, as suffragan of the Metropolitan of the Late Roman province of Osroene : first as Latin - (meanwhile suppressed) and currently as Maronite titular bishopric.[68]

Callinicum of the Romans

[69] No later than the 18th century, the diocese was nominally restored as Latin Titular bishopric of Callinicum (Latin), adjective Callinicen(sis) (Latin) / Callinico (Curiate Italian).

In 1962 it was suppressed, to establish immediately the Episcopal Titular bishopric of Callinicum of the Maronites (see below)

It has had the following incumbents, all of the fitting episcopal (lowest) rank :

- Matthaeus de Robertis (1729.07.06 – death 1733) (born Italy) no prelature

- Meinwerk Kaup, Benedictine Order (O.S.B.) (1733.09.02 – death 1745.07.24) as Auxiliary Bishop of Paderborn (Germany) (1733.09.02 – 1745.07.24)

- Anton Johann Wenzel Wokaun (1748.09.16 – 1757.02.07) as Auxiliary Bishop of Praha (Prague, Bohemia) (1748.09.16 – 1757.02.07)

- Nicolas de La Pinte de Livry, Norbertines (O. Praem.) (born France) (1757.12.19 – death 1795) no prelature

- Luigi Pietro Grati, Servites (O.S.M.) (born Italy) (1828.12.15 – death 1849.09.17) as Apostolic Administrator of Terracina (Italy) (1829 – 1833), Apostolic Administrator of Priverno (Italy) (1829 – 1833), Apostolic Administrator of Sezze (Italy) (1829 – 1833) and on emeritate

- Godehard Braun (1849.04.02 – death 1861.05.22) as Auxiliary Bishop of Diocese of Trier (Germany) (1849.04.02 – 1861.05.22)

- Hilarion Silani, Sylvestrines (O.S.B. Silv.) (1863.09.22 – 1879.03.27) while Bishop of Colombo (Sri Lanka) (1863.09.17 – 1879.03.27)

- Aniceto Ferrante, Oratorians of Philip Neri (C.O.) (1879.05.12 – death 1883.01.19) on emeritate as former Bishop of Gallipoli (Italy) (1873.03.20 – 1879.05.12)

- Luigi Sepiacci, Augustinians (O.E.S.A.) (1883.03.15 – cardinalate 1891.12.14) as Roman Curia official : President of Pontifical Ecclesiastical Academy (1885.08.07 – 1886.06.28), Secretary of Sacred Congregation of Bishops and Regulars (1886.06.28 – 1892.08.01), created Cardinal-Priest of S. Prisca (1891.12.17 – death 1893.04.26), Prefect of Sacred Congregation of Indulgences and Sacred Relics (1892.08.01 – 1893.04.26)

- Pasquale de Siena (1898.09.23 – death 1920.11.25) as Auxiliary Bishop of Napoli (Napels, southern Italy) (1898.09.23 – 1920.11.25)

- Joseph Gionali (1921.11.21 – 1928.06.13) as Abbot Ordinary of Territorial Abbacy of Shën Llezhri i Oroshit (Albania) (1921.08.28 – 1928.06.13), later Bishop of Sapë (Albania) (1928.06.13 – 1935.10.30), emeritate as Titular Bishop of Rhesaina (1935.10.30 – death 1952.12.20)

- Barnabé Piedrabuena (1928.12.17 – 1942.06.11) as emeritate; previously Titular Bishop of Cestrus (1907.12.16 – 1910.11.08) as Auxiliary Bishop of Tucumán (Argentina) (1907.12.16 – 1910.11.08 - first time), Bishop of Catamarca (Argentina) (1910.11.08 – 1923.06.11), again Bishop of Tucumán (1923.06.11 – retired 1928.12.17)

- Tomás Aspe, Friars Minor (O.F.M.) (born Spain) (1942.11.21 – 1962.01.22) on emeritate as former Bishop of Cochabamba (Bolivia) (1931.06.08 – 1942.11.21)

Callinicum of the Maronites

[70] In 1962 the simultaneously suppressed Latin Titular see of Callinicum (see above) was in turn restored, now for the Maronite Church (Eastern Catholic, Antiochian Rite) as Titular bishopric of Callinicum (Latin), Callinicen(sis) Maronitarum (Latin adjective) / Callinico (Curiate Italian).

It has had the following incumbents, so far of the fitting Episcopal (lowest) rank :

- Francis Mansour Zayek (1962.05.30 – 1971.11.29) as first Auxiliary Bishop of São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) (1962.05.30 – 1966.01.27), then Apostolic Exarch of United States of America of the Maronites (USA) (1966.01.27 – 1971.11.29); later promoted with that see as only Eparch (Bishop) of Saint Maron of Detroit of the Maronites (USA) (1971.11.29 – 1977.06.27), restyled as that see moved to first Eparch (Bishop) of Saint Maron of Brooklyn of the Maronites (USA) (1977.06.27 – 1982.12.10), personally promoted Archbishop-Bishop of Saint Maron of Brooklyn of the Maronites (1982.12.10 – retired 1996.11.11); died 2010

- John George Chedid (1980.10.13 – 1994.02.19) as Auxiliary Bishop of Saint Maron of Brooklyn of the Maronites (USA) (1980.10.13 – 1994.02.19); laer first Eparch (Bishop) of its daughter see Our Lady of Lebanon of Los Angeles of the Maronites (East Coast of USA) (1994.02.19 – retired 2000.11.20), died 2012

- Samir Mazloum (1996.11.11 – ...), as Bishop of Curia of the Maronites (2000 – retired 2011.08.13) and on emeritate.

Media

The Islamic State banned all media reporting outside its own efforts, kidnapping and killing journalists. However, a group calling itself Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently operated within the city and elsewhere during this period.[71] In response, ISIL has killed members of the group.[72] A film about the city made by RBSS was released internationally in 2017, premiering and winning an award at that year's Sundance Film Festival.

In January 2016, a pseudonymous French author named Sophie Kasiki published a book about her move from Paris to the besieged city in 2015, where she was lured to perform hospital work, and her subsequent escape from ISIL.[73][74]

Transportation

Prior to the Syrian Civil War the city was served by Syrian Railways.

Climate

| Climate data for Raqqa | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18 (64) |

22 (72) |

26 (79) |

33 (91) |

41 (106) |

42 (108) |

43 (109) |

47 (117) |

41 (106) |

35 (95) |

30 (86) |

21 (70) |

47 (117) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

14 (57) |

18 (64) |

24 (75) |

31 (88) |

36 (97) |

39 (102) |

38 (100) |

33 (91) |

29 (84) |

21 (70) |

16 (61) |

26 (79) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

3 (37) |

5 (41) |

11 (52) |

15 (59) |

18 (64) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

16 (61) |

12 (54) |

7 (45) |

4 (39) |

11 (52) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7 (19) |

−7 (19) |

−2 (28) |

2 (36) |

8 (46) |

12 (54) |

17 (63) |

13 (55) |

10 (50) |

2 (36) |

−2 (28) |

−5 (23) |

−7 (19) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 22 (0.9) |

18.2 (0.72) |

24.3 (0.96) |

10.2 (0.40) |

4.5 (0.18) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.00) |

3.1 (0.12) |

12.4 (0.49) |

13.6 (0.54) |

108.4 (4.31) |

| Average precipitation days | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 36.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 72 | 60 | 53 | 45 | 34 | 38 | 41 | 44 | 49 | 60 | 73 | 54 |

| Source 1: [75] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: [76] | |||||||||||||

Notable locals

- Al-Battani, astronomer, astrologer and mathematician (c. 858 – 929)

- Abdul-Salam Ojeili, novelist and politician (1918–2006)

- Harun al-Rashid, fifth Abbasid Caliph (786–809)

- Khalaf Ali Alkhalaf, poet and writer (b. 1969)

- Yassin al-Haj Saleh, writer and dissident (b. 1961)

See also

- Battle of Callinicum

- Raqqa offensive (2016)

- Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently

References

- "Ar-Raqqa Governorate Panoramic Report - December 2019" (PDF). Assistance Coordination Unit. 24 December 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "2004 Census Data for ar-Raqqah nahiyah" (in Arabic). Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015. Also available in English: "2004 Census Data *". UN OCHA. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- D. Remnick (22 November 2015) (22 November 2015). Telling the Truth About ISIS and Raqqa. The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 19 December 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- "Raqqa: IS 'capital' falls to US-backed Syrian forces". BBC News. 17 October 2017. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Meinecke 1995, p. 410.

- Isidoros of Charax, Parthian Stations, § 1.2

- Heracleensis, Marcianus (15 September 1839). "Périple de Marcien d'Héraclée, Épitome d'Artemidore, Isidore de Charax, etc., ou, Supplément aux dernières éditions des Petits géographes: d'après un manuscrit grec de la Bibliothèque Royale, avec une carte". A L'Imprimerie Royale – via Google Books.

- Mango 1991, p. 1094.

- Revue de l'Orient chrétien Archived 19 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, VI (1901), p. 197.

- Henderson, Julian (2005). Antiquity.CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

- Ababsa, Myriam (20 September 2010). "Chapitre 1. " Politique des chefs " en Jazîra et " politique des notables " à Raqqa : La naissance d'une ville de front pionnier (1865-1946)". Raqqa, territoires et pratiques sociales d'une ville syrienne. Contemporain publications. Beyrouth: Presses de l’Ifpo. pp. 25–66. ISBN 9782351592625. Archived from the original on 3 June 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Stefan Winter, "The Province of Raqqa under Ottoman Rule, 1535–1800" in Journal of Near Eastern Studies 68 (2009), 253–67.

- "لمحة عن تاريخ الرقة | موسوعة جياي كورمنج ™". موسوعة جياي كورمنج ™ (in Arabic). 14 November 2016. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Syria rebels capture northern Raqqa city". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Under the black flag of al-Qaeda, the Syrian city ruled by gangs of extremists". The Telegraph. 12 May 2013. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- "Al-Qaeda sets up complaints department". The Telegraph. 2 June 2013. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- "Syria, anti-Assad rebel infighting leaves 700 dead, including civilians". AsiaNews. 13 January 2014. Archived from the original on 25 June 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- Asia News. 27 September 2013, As jihadist rebels burn two Catholic churches in al-Raqqah, Assad's enemies openly split Archived 2 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- "Inside ISIS: 2 women go undercover in Raqqa". The Foreign Desk. 14 March 2016. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- "Life in a Jihadist Capital: Order With a Darker Side". New York Times. 23 July 2014. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

After capturing the largest, the Armenian Catholic Martyrs Church, ISIS removed its crosses, hung black flags from its façade and converted it into an Islamic center that screens videos of battles and suicide operations to recruit new fighters.

- "Armenian Catholic Church of the Martyrs | WORLD News Group". Archived from the original on 31 August 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "The Mysterious Fall of Raqqa, Syria's Kandahar". Al-Akhbar. 8 November 2013. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "Syrian activists flee abuse in al-Qaeda-run Raqqa". BBC News. 13 November 2013. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "Islamic State torches churches in Al-Raqqa". Syria Newsdesk. 26 September 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "France Drops 20 Bombs on IS Stronghold Raqqa". Sky News. 15 November 2015. Archived from the original on 16 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Fadel, Leith. "Civilians rise up against ISIS rule in Raqqa City: government". Al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- NICHOLS, HANS; BRUTON, F. BRINLEY (26 October 2016). "Raqqa Offensive Against ISIS to Begin Within Weeks: Ash Carter". NBC News. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- The Islamic State Is Gone. But Raqqa Lies in Pieces Archived 4 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine Time, October 2017.

- Raqqa: US coalition 'wiped city off Earth', Russia says Archived 5 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC, 22 October 2017.

- "Victory through annihilation: Ruin, death & discord left after US-led coalition takes Raqqa". RT International. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Raqqa: Isis 'capital' liberated by US-backed forces - but civilians face months of hardship with city left devastated Archived 9 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Independent, 17 October 2017.

- Foreign Ministry: Raqqa still occupied, can only be considered liberated when Syrian Army enters it Archived 29 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine SANA, 29 October 2017.

- "Hospital In Raqqa Treats Women And Children Free Of Charge". Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "The First Functioning Hospital Opens In Raqqa After ISIS". Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Raqqa Civil Council Rehabilitates Schools For The New Academic Year". Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Newly Rebuilt Hospital In Raqqa Is Now Welcoming Patients". Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Civil Society In Raqqa, Syria, Tackles Extremism Among Youth". Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Raqqa Municipality Begins Rebuilding Roads In The City". Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Local Authorities Rebuild Raqqa Bridge After ISIS Destruction". Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Water crisis blights the lives of residents in Raqqa". Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Irrigation Canals In Raqqa Provide Water To 10,000 Hectares Of Land". Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Raqqa Stadium: From ISIS Prison To Centre Of Sports In The City". Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Rehabilitation of amusement park in Raqqa". 26 May 2018. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Progress in The City Of Raqqa, One Year On From ISIS". Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- "Syria Crisis: Northeast Syria Situation Report No. 30 (1 November - 14 December 2018)". UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 14 December 2018. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "100,000 Return to Raqqa as UN Aid Reaches Syrian City". Asharq Al-Awsat. 4 April 2018. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "U.S.-backed forces announce three-day curfew in Raqqa city". 24 June 2018. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019 – via www.reuters.com.

- "Despite ISIS' Destructive Legacy, Raqqa Experiences Peace Post-Liberation". Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- Desk, News (8 February 2019). "Over 60 ISIS operatives captured in Raqqa city". Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- "Largest ISIS mass grave yet found outside Syria's Raqqa. 22 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019". Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- "International Organisations Rebuild Houses In Raqqa As Part Of 'Shelter Project'". Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- "Syria: 200,000 People Are Using The Newly Rebuilt Raqqa Bridge". Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- "Weteni Hospital of Raqqa goes into service". ANF News.

- Abdulrahim, Raja (14 October 2019). "Kurdish-Syrian Pact Scrambles Mideast Alliances". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- "New map of northern Syria after Turkish offensive and SDF-SAA agreement". Al-Masdar News. 18 October 2019. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Website of the Scanning for Syria project at the Leiden University". Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- "Website of the Scanning for Syria project at the Leiden-Delft-Erasmus Centre for Global Heritage and Development". Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- "NWO Website for the grant of the Scanning for Syria. Reconstruction and enhanced reality of Assyrian clay tablets (1200 BC) recently stolen from Raqqa Museum, Syria. project". Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- Nieuwenhuyse, Olivier; Hiatlih, Khaled; al-Fakhri, Ayham; Haqi, Rasha; Ngan-Tillard, Dominique; Mara, Hubert; Burch Joosten, Katrina (2019), "Focus Raqqa: Schutz für das archäologische Erbe des Museums von ar-Raqqa", Antike Welt (in German), wbg Philipp von Zabern, pp. 76–83, retrieved 14 May 2020

- Ngan-Tillard, Dominique (5 June 2018), Scanning for Syria - digital book of cuneiform tablet T98-34, Delft, Netherlands: TU Delft, doi:10.4121/uuid:0bd4470b-a055-4ebd-b419-a900d3163c8a, retrieved 14 May 2020, KBytes: 48600

- "Website of the Europa Nostra Award for the Scanning for Syria project". Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- "NPNF2-10. Ambrose: Selected Works and Letters - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- A.D. Lee, From Rome to Byzantium AD 363 to 565 Archived 26 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Oxford University Press 2013 ISBN 978-0-74866835-9)

- Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Leipzig 1931, p. 437

- Michel Lequien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus Archived 3 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Paris 1740, Vol. II, coll. 969–972

- Siméon Vailhé in Échos d'Orient 1907, p. 94 Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine e p. 145 Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 856

- "Titular See of Callinicum". GCatholic. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- http://www.gcatholic.org/dioceses/former/t0378.htm Archived 18 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine GCatholic

- K. Shaheen (2 December 2015) - Airstrikes have become routine for people in Raqqa, says activist Archived 25 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian [Retrieved 30 December 2015]

- British Broadcasting Corporation (28 December 2015) - Anti-Islamic State journalist murdered in Turkey Archived 12 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC [Retrieved 30 December 2015]

- Willsher, Kim (8 January 2016). "I went to join Isis in Syria, taking my four-year-old. It was a journey into hell". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Saavedra, Laetitia; Duquesne, Margaux (8 January 2016). "Les femmes djihadistes étrangères se comportent comme des colons en Syrie". FranceInter (in French). Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- "Climate statistics for Ar-Raqqah". World Weather Online. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- "Averages for Ar-Raqqah". Weather Base. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

Further reading

- Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn (2006). Raqqa revisited: ceramics of Ayyubid Syria. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 1588391841.

- Mango, Marlia M. (1991). "Kallinikos". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1094. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meinecke, Michael (1991). "Raqqa on the Euphrates. Recent Excavations at the Residence of Harun er-Rashid". In Kerner, Susanne (ed.). The Near East in Antiquity. German Contributions to the Archaeology of Jordan, Palestine, Syria, Lebanon and Egypt II. Amman. pp. 17–32.

- Meinecke, Michael (1991) [1412 AH]. "Early Abbasid Stucco Decoration in Bilad al-Sham". In Muhammad Adnan al-Bakhit – Robert Schick (ed.). Bilad al-Sham During the 'Abbasid Period (132 AH/750 AD – 451 AH/1059 AD). Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference for the History of the Bilad al-Sham 7–11 Sha'ban 1410 AH/4–8 March 1990, English and French Section. Amman. pp. 226–237.

- Meinecke, Michael (1995). "al-Raḳḳa". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden and New York: BRILL. pp. 410–414. ISBN 90-04-09834-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meinecke, Michael (1996). "Forced Labor in Early Islamic Architecture: The Case of ar-Raqqa/ar-Rafiqa on the Euphrates". Patterns and Stylistic Changes in Islamic Architecture. Local Traditions Versus Migrating Artists. New York, London. pp. 5–30. ISBN 0-8147-5492-9.

- Meinecke, Michael (1996). "Ar-Raqqa am Euphrat: Imperiale und religiöse Strukturen der islamischen Stadt". Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft (128): 157–172.

- Heidemann, Stefan (2002). "Die Renaissance der Städte in Nordsyrien und Nordmesopotamien. Städtische Entwicklung und wirtschaftliche Bedingungen in ar-Raqqa und Harran von der Zeit der beduinischen Vorherrschaft bis zu den Seldschuken". Islamic History and Civilization. Studies and Texts. Leiden: Brill (40).

- Ababsa, Myriam (2002). "Les mausolées invisibles: Raqqa, ville de pèlerinage ou pôle étatique en Jazîra syrienne?". Annales de Géographie. 622: 647–664.

- Stefan Heidemann – Andrea Becker (edd.) (2003). Raqqa II – Die islamische Stadt. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Daiber, Verena; Becker, Andrea, eds. (2004). Raqqa III – Baudenkmäler und Paläste I, Mainz. Philipp von Zabern.

- Heidemann, Stefan (2005). "The Citadel of al-Raqqa and Fortifications in the Middle Euphrates Area". In Hugh Kennedy (ed.). Muslim Military Architecture in Greater Syria. From the Coming of Islam to the Ottoman Period. History of Warfare. 35. Leiden. pp. 122–150.

- Heidemann, Stefan (University of Jena) (2006). "The History of the Industrial and Commercial Area of 'Abbasid al-Raqqa Called al-Raqqa al-Muhtariqa" (PDF). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 69 (1): 32–52. doi:10.1017/s0041977x06000024. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2015.

- Videos

- "After the fall of ISIS caliphate, its capital remains a city of the dead". PBS Newshour. 4 April 2019.

- "An inside look at the former capital of ISIS". CBC News. 6 November 2017.

- "Inside ISIS's Former Capital: The Forgotten People of Raqqa". The New York Times. 1 April 2019.

- "Life Inside the ISIS Home Base of Raqqa, Syria". The Wall Street Journal. 15 September 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raqqa. |

Current news and events

- eraqqa Website for news relating to Raqqa