Multi-speed Europe

Multi-speed Europe or two-speed Europe (called also "variable geometry Europe" or "Core Europe" depending on the form it would take in practice) is the idea that different parts of the European Union should integrate at different levels and pace depending on the political situation in each individual country. Indeed, multi-speed Europe is currently a reality, with only a subset of EU countries being members of the eurozone and of the Schengen area. Like other forms of differentiated integration such as à la carte and variable geometry, "multi-speed Europe" arguably aims to salvage the "widening and deepening of the European Union" in the face of political opposition.

Reasons and actuality of the concept

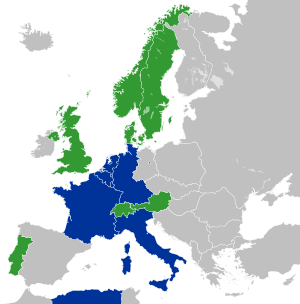

The concept entered political discourse when, after the end of the Cold War, an eastward enlargement of the European Union began to materialise and the question arose how "widening" could be made compatible with "deepening",[1] i.e., how the imminent enlargement process could be prevented from diluting the idea of an "ever closer union among the peoples of Europe", as the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community of 1957 had put it. In 1994 – still at a time of the EU12 – the German Christian Democrats Wolfgang Schäuble and Karl Lamers published a document[2] in which they called for a Kerneuropa (= core Europe). This idea envisaged that "core Europe" would have a "centripetal effect", a magnetic attraction for the rest of Europe. A precursor to that concept had been a proposal by two advisors to German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, Michael Mertes and Norbert J. Prill, published as early as July 1989. Mertes and Prill called for a concentric circles Europe, built around a federal core consisting of the Inner Six (EU6) and like-minded EU member states.[3] In 1994 they partly revoked their original idea, arguing that the post-Cold War EU would rather look like a "Europe of Olympic rings" than a "Europe of concentric circles".[4]

The multi-speed Europe concept has been debated for years in European political circles, as a way to solve some institutional issues. The concept is that the more members there are in the Union, the more difficult it becomes to reach consensus on various topics, and the less likely it is that all would advance at the same pace in various fields.

Intermediate forms could be limited to some areas of close cooperation, as some historical examples are given below. It is also possible now for a minimum of nine EU member states to use enhanced co-operation, but this new framework has been used only once. A second proposal, a unified European patent, is nearing completion [as of December 2010] with only two countries (Italy and Spain) not participating.[5]

The idea of a multi-speed Europe has been revived because of the following initiatives:

- the Euro with 19 EU member-states and one more in ERM II. All but two states (Denmark, United Kingdom) have agreed by treaty to join but at least one of those treaty signatories (Sweden) has made no further steps to do so.

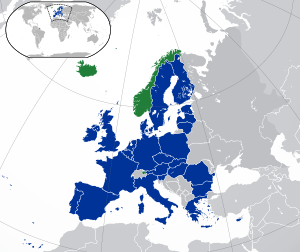

- the Schengen area Treaty leading to a common border for many EU states (as of April 2020, it excludes five EU member states: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Ireland, and Romania, but includes four non-EU members - Norway, Switzerland, Iceland and Liechtenstein). Baroness Williams of Crosby, in a House of Lords debate, asserted that Ireland only reluctantly agreed to stay out of the treaty to avoid creating a physical border between the Republic and Northern Ireland because the UK had chosen not to participate in the scheme.[6]

- other initiatives limited to some states, such as the European Defence initiative and Prüm Convention.

Furthermore, important events were

- the enlargement of the European Union to 28 member-states and in the forthcoming years other candidates (Turkey, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Iceland) where new members initially don't join the Schengen area and the Eurozone for some time.

- the European Convention that led to the European Constitution that was signed in 2004 by the 25 Heads of State, but was not ratified by all national parliaments or assemblies and so failed. Later most of its provisions were adopted through the Treaty of Lisbon that included additional opt-outs for some states.

- differences of view between EU members on some foreign diplomatic and military issues. In a 2004 article The Economist compared the variances of Europe to a lake that has many deep parts (areas in which countries are similar) and many shallow parts (areas in which countries have major differences).[7]

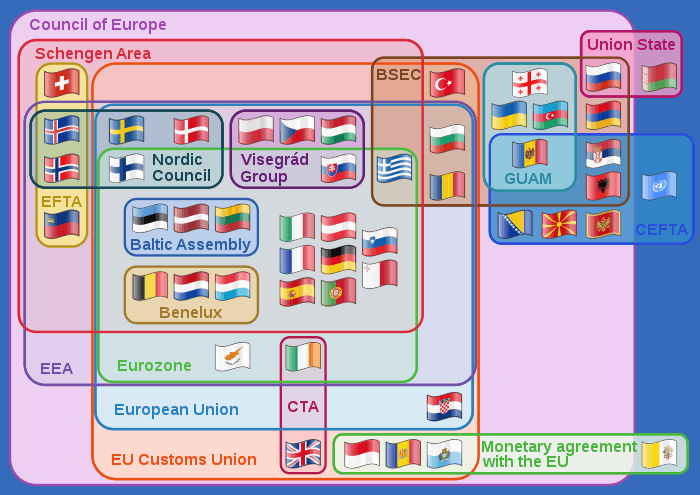

A clickable Euler diagram showing the relationships between various multinational European organisations and agreements.

A clickable Euler diagram showing the relationships between various multinational European organisations and agreements.

Currently in the EU there are the following cases of non-uniform application of the European Union law:

| permanent deviations[8] | request by states to cooperate more than EU (post-accession: request to participate at EU level instead of less) |

request by states to cooperate less than general EU level |

| allowed by the EU | Enhanced co-operation | Opt-outs in the European Union Minor EU law derogations or exemptions special territories status |

| not allowed by the EU | Mechanism for Cooperation and Verification Eurozone/Schengen suspensions (post accession: benchmarks for adoption of EU level) |

|

Overview of non-uniformity inside the EU

| Participant | Schengen | AFSJ | CFR | Euro | EEA | ESM | EFC | SRM | Euro+ | CSDP | Prüm | Patent | Divorce | Symbols |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| c | x | x | c | x | o | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| c | x | x | c | c | o | x | c | o | x | o | o | o | o | |

| c | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | o | x | |

| x | x | x | c | x | o | x | c | o | x | o | x | o | o | |

| x | o | x | o | x | o | x | c | x | o | o | x | o | o | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x[9] | o | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | o | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | c | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | c | x | o | x | x | o | x | x | x | x | x | |

| o | o | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | o | o | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | c | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | x | o | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | o | |

| x | x | o | c | x | o | x | c | x | x | o | x | o | o | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | c | x | x | x | |

| c | x | x | c | x | o | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | x | |

| x | x | x | c | x | o | x | o | o | x | c | x | o | o | |

| Participant | Schengen | AFSJ | CFR | Euro | EEA | ESM | EFC | SRM | Euro+ | CSDP | Prüm | Patent | Divorce | Symbols |

x – member

c – conditions to be fulfilled before joining or candidate

o – non-member

Pol. : politics — Soc. : society — Eco. : economy

Participation of European countries in non EU-only integration initiatives

- For integration activities not initiated by the EU see European integration

A number of countries have special relations to the European Union implementing many of its regulations. Prominently there are Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and Liechtenstein which are the only remaining EFTA members while all other former EFTA members have converted into EU members. Through agreements Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein (not including Switzerland) are members of the European Economic Area since 1994. As a consequence of taking part in the EU single market they need to adopt part of the Law of the European Union. Formally they would not need to fund the EU government but in practice they have opted to take on their part of financing EU institutions as required by EU law (see EEA and Norway Grants) with the financial footprint of Norway being equal to that of an EU member since 2009. Especially Norway and Iceland are known to forfeit EU membership on the basis of EU fishery regulations that they want to opt out on. Both Norway and Iceland have signed and implemented the Schengen zone agreements from the start. During the turmoils of the financial crisis, Iceland was looking into membership of the Eurozone and it did apply for EU membership in 2009. Norway has joined all EU political treaties and it has applied to EU membership multiple times but while fulfilling the requirements the membership was rejected by referenda in 1972 and 1994. This leaves Norway to be integrated into Inner Europe's institutions while not being part their governing body.

| Participant | Schengen | Euro | CU | EEA | Energy Community | ECT | ECAA | EEAgency | EMCDDA | EMSA | EASA | ERA | EDA | ESA | Prüm | NATO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| s | x | |||||||||||||||

| o | x | |||||||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| c | c | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| c | c | x | c | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | ||

| c | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | |||

| x | c | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | |||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | s | |||||||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | c | x | |

| x | c | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | |||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | c | x | |

| x[10] | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | ||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | ||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | |||

| x | x | s | ||||||||||||||

| s | s | x | s | |||||||||||||

| x[10] | x | x | x | |||||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| x | x | o | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| x | c | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | o | x | |

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | c | x | |

| c | c | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| s | x | s | ||||||||||||||

| x | x | x | ||||||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| x | c | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | c | ||

| x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| x | x | |||||||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| s | ||||||||||||||||

| Participant | Schengen | Euro | CU | EEA | Energy Community | ECT | ECAA | EEAgency | EMCDDA | EMSA | EASA | ERA | EDA | ESA | Prüm | NATO |

– member of the E.U.

– official candidate to join the E.U.

– recognised potential candidate to join the E.U.

x – member

c – conditions to be fulfilled before joining

s – unilateral adoption/participation through another state who is a member/some instruments signed, but not yet ratified

o – observer

Post-Brexit-vote revival of "multispeed Europe" ideas

In March 2017, European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker released a five-point view of possible courses for the EC and its to-be-27 post-Brexit members, looking forward to the year 2025. The points, among which Juncker expressed no preference, "range from standing down from policing of government financing of companies, for example, to a broader pullback that would essentially strip the EU back to being merely a single market", per one report. The updated possibilities would entail member countries or groups of countries adopting different levels of participation with the union. The EC was approaching a March meeting of the 27 members in Rome and Juncker's paper addressed the options that "once invited scorn from convinced Europhiles" and seemed maybe even to have some backing "of lifelong federalists" like the president.[11]

See also

- Agencies of the European Union – different examples of non-EU states participation and non-participation of some EU members

- Enhanced co-operation

- European Free Trade Association (EFTA)

- European integration

- Euroscepticism

- Eurosphere

- Eurozone

- Federal Europe

- Inner Six

- Mechanism for Cooperation and Verification

- Opt-outs in the European Union

- Pro-Europeanism

- Schengen Agreement

References

- Marcin Zaborowski: Germany and EU Enlargement: From Rapprochement to "Reaproachment"? In: Helene Sjursen (Ed.), Enlargement in perspective, ARENA Report February 2005, p. 46.

- Karl Lamers / Wolfgang Schäuble: Überlegungen zur europäischen Politik (Reflections on European Policy). See also Gilles Andréani: What future for federalism?, Centre for European Reform Essays, September 2002, ISBN 1-901229-33-5, p. 7-8.

- Michael Mertes / Norbert J. Prill: Der verhängnisvolle Irrtum eines Entweder-Oder. Eine Vision für Europa, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 19 July 1989.

- Michael Mertes / Norbert J. Prill: Es wächst zusammen, was zusammengehören will. “Maastricht Zwei” muss die Europäische Union flexibel machen, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 9 December 1994, p. 11.

- "Countries press ahead with limited single EU patent plan", out-law.com, 17 December 2010.

- Parliament of the United Kingdom (12 March 1998). "Volume: 587, Part: 120 (12 Mar 1998: Column 391, Baroness Williams of Crosby)". House of Lords Hansard. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- 'Coalitions for the willing', The Economist, February 1, 2007.

- In addition to the permanent deviations there are temporary transition periods for the application of certain EU law provisions in some member states, but these have an already set dates for lapsing.

- Signed but not in force.

- De facto uses the euro.

- Valentine Pop, "Once Scorned, ‘Multispeed Europe’ Is Back" (subscription), Wall Street Journal, March 1, 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-01.