National identity cards in the European Economic Area

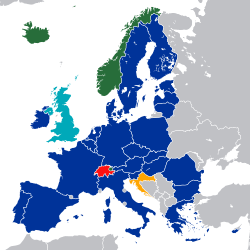

National identity cards are issued to their citizens by the governments of all European Economic Area (EEA) member states except Denmark, Ireland, Iceland, Norway and the United Kingdom. Citizens holding a national identity card, which states citizenship of an EEA member state or Switzerland, can use it as an identity document within their home country, and as a travel document to exercise the right of free movement in the EEA and Switzerland.[1] However, identity cards that do not state citizenship of an EEA member state or Switzerland, including national identity cards issued to residents who are not citizens, are not valid as travel documents within the EEA and Switzerland.

National identity cards are often accepted in other parts of the world for unofficial identification purposes (such as age verification in commercial establishments that serve or sell alcohol, or checking in at hotels) and sometimes for official purposes such as proof of identity/nationality to authorities (especially machine-readable cards).

Four EEA member states (Denmark, Iceland, Norway and the United Kingdom) do not issue cards defined by the EU as national identity cards to their citizens. However, Norway is expected to start issuing such cards from 2020.[2] Ireland issues a passport card which is valid as a national identity card in the EEA and Switzerland.[3] At present, citizens from Denmark, Iceland, Norway and the United Kingdom can only use a passport as a travel document when travelling within EEA member states and Switzerland.[4]

As national identity cards are less bulky and usually cheaper than passports, ID card ownership in the EEA and Switzerland is much more widespread than passport ownership.[5]

Use

Travel document

As an alternative to presenting a passport, EEA and Swiss citizens are entitled to use a valid national identity card as a stand-alone travel document to exercise their right of free movement in the European Economic Area, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.[6][7]

When travelling within the Common Travel Area, other valid identity documentation (such as a driving licence) is often sufficient for British and Irish citizens.[8] When travelling within the Nordic Passport Union, no identity documentation is legally required by Nordic citizens.

Strictly speaking, it is not necessary for an EEA or Swiss citizen to possess a valid national identity card or passport to enter the EEA, Switzerland and the UK. In theory, if an EEA or Swiss citizen can prove their nationality by any other means (e.g. by presenting an expired national identity card or passport, or a citizenship certificate), they must be permitted to enter the EEA, Switzerland and the UK. An EEA or Swiss citizen who is unable to demonstrate their nationality satisfactorily must, nonetheless, be given 'every reasonable opportunity' to obtain the necessary documents or to have them delivered within a reasonable period of time.[9][10][11][7][12]

Additionally, EEA and Swiss citizens can enter the following countries and territories outside the EEA and Switzerland on the strength of their national identity cards alone, without the need to present a passport to the border authorities:

|

Of these countries, however, the following only accept national ID cards of EEA/Swiss citizens for short-term visits, and require a passport to take up residency:

- 1. Unlike Gibraltar, the British overseas territory of Akrotiri and Dhekelia and the British Crown Dependencies of Guernsey, the Isle of Man, and Jersey were not part of the European Union. Nonetheless, EEA and Swiss citizens are able to use their national identity cards as travel documents to enter all of these territories.

- 2. Monaco is de facto part of the Schengen Area under an arrangement with France, while San Marino and Vatican City are enclaves of Italy with open land borders. Further information: Schengen Area § Status of the European microstates.

- 3. Only machine-readable ID cards.

- 4. Except for nationals of Liechtenstein.

- 5. Nationals of France may stay for a maximum of 6 months with an ID card. Other EEA/Swiss nationals (except Croatians) may enter on an ID card only if in transit to a third country and staying for max 14 days.

- 6. Except for Nordic citizens.

Turkey allows citizens of Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland to enter for short-term visits using a national identity card.[27] Egypt allows citizens of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, and Portugal to enter using a national identity card for short-term visits.[28][29] Tunisia allows nationals of Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland to enter using a national identity card if travelling on an organized tour. Anguilla, Dominica, and Saint Lucia allow nationals of France to enter using a national ID card, while Dominica de facto also allows nationals of (at least) Germany and Sweden to enter with a national ID card (as of March 2016). Gambia allows nationals of Belgium to enter using a national ID card.[30] Finally, Greenland allows Nordic citizens to enter with a national ID card (only Sweden and Finland have them, whereas Norway will introduce them in 2020). In practice, all EEA and Swiss citizens can use their ID cards, because no passport control takes place on arrival in Greenland, only by the airline at check-in and the gate, and both Air Greenland and Icelandair accept any EEA or Swiss ID card.

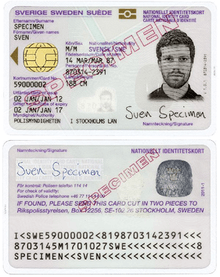

Although, as a matter of European law, holders of a Swedish national identity card are entitled to use it as a travel document to any European Union member state (regardless of whether it belongs to the Schengen Area or not), Swedish national law did not recognise the card as a valid travel document outside the Schengen Area until July 2015[31] in direct violation of European law. What this meant in practice was that leaving Schengen directly from Sweden (i.e., without making a stopover in another Schengen country) with the card was not possible. This partially changed in July 2015, when travel to non-Schengen countries in the EU (but not outside, even if the destination country accepts the ID card) was permitted.[32] Sweden continues to allow travel to the United Kingdom during the Brexit transition period).[33][34]

Similarly, Finnish citizens cannot leave Finland directly for a non-EU/EFTA country with only their ID cards.[35]

Additional checks for some citizens

At the external border crossing points of the Schengen Area, if a traveller presents a travel document without a machine readable zone and the border guard has 'doubt about his/her identity', the traveller may be requested to undergo a more in-depth 'second line' check.[10] In practice, this means that Greek citizens who present a Greek identity card and Italian citizens who present an Italian paper identity card could be subject to additional checks and delay when entering/leaving the Schengen Area.[36]

UK Border Force (UKBF) officers have been known to place extra scrutiny on and to spend longer processing national identity cards issued by certain member states which are deemed to have limited security features and hence more susceptible to tampering/forgery. As a matter of policy, UKBF officers are required to examine physically all passports and national identity cards presented by EEA and Swiss citizens for signs of forgery and tampering.[37] By contrast, under the previous legal regime that was in force until 7 April 2017, their counterparts in the Schengen Area were only obliged to perform a 'rapid' and 'straightforward' visual check for signs of falsification and tampering, and were not obliged to use technical devices – such as document scanners, UV light and magnifiers – when EEA and Swiss citizens presented their passports or national identity cards at external border checkpoints.[38]

Moreover, as a matter of policy, UKBF officers are required to check every EEA and Swiss citizen and their passport/national identity card against the Warnings Index (WI) database.[37] By contrast, their counterparts in the Schengen Area were previously not legally obliged to check the passports/national identity cards of EEA and Swiss citizens against a database of lost/stolen/invalidated travel documents (and, if they did so, they could only perform a 'rapid' and 'straightforward' database check, and could only check to see if the traveller was on a database containing persons of interest on a strictly 'non-systematic' basis where such a threat was 'genuine', 'present' and 'sufficiently serious').[38] However, with effect from 7 April 2017, it is now mandatory for border guards in the Schengen Area to check on a systematic basis the travel documents of all EEA and Swiss citizens crossing external borders against relevant databases.[39]

For these reasons, when presented with a non-machine readable identity card, it can take up to four times longer for a UKBF officer to process the card as the officer has to enter the biographical details of the holder manually into the computer to check against the WI database and, if a large number of possible matches is returned, a different configuration has to be entered to reduce the number of possible matches.[40]

For example, at Stansted Airport, UKBF officers have been known to take longer to process Italian paper identity cards because they often need to be taken out of plastic wallets,[41] because they are particularly susceptible to forgery/tampering[42] and because, as non-machine readable documents, the holders' biographical details have to be entered manually into the computer.[41] UKBF officers at the juxtaposed controls have been known to take longer to verify Romanian identity cards.[43]

According to the European Commission, some holders of Italian paper identity cards have been told by UKBF officers at Heathrow Airport that their ID card was 'just a piece of paper' and were advised to apply for a passport to use the next time that they enter the UK. Thus, they were 'confronted with obstacles to their free movement'.[44]

As of 20 May 2019, the UK Border Force advises EU/EEA/Swiss citizens to use their passport instead of their national identity card at the UK border because 'passports are faster for our Border Force officers to process' and 'you can use your EU passport at our eGates'.[45]

According to statistics published by Frontex, in 2015 the top 6 EU member states whose national identity cards were falsified and detected at external border crossing points of the Schengen Area were Italy, Spain, Belgium, Greece, France and Romania.[46] These countries remained the top 6 in 2016.[47]

Identification document

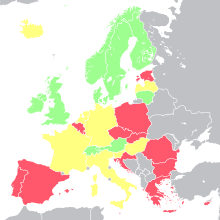

| National identity card required |

| Some form of identity documentation required |

| Identity documentation optional |

- Usage in own country

There are varying rules on domestic usage of identity documents. Some countries demand the usage of the national identity card or a passport. Other countries allow usage of other documents like driver's licences.

In some countries, e.g. Austria, Finland and Sweden, national identity cards are fully voluntary and not needed by everyone, as identity documents like driving licences are accepted domestically. In these countries only a minority have a national identity card, since a majority have a passport and a driving licence and don't need more identity documents. This is also true for Ireland where those who have a passport and a driving licence have less need for the passport card.

- Usage outside own country

EEA and Swiss citizens exercising their right of free movement in another EEA member state, Switzerland or the UK are entitled to use their national identity card as an identification document when dealing not just with government authorities, but also with private sector service providers. For example, where a supermarket in the UK refuses to accept a German national identity card as proof of age when a German citizen attempts to purchase an age-restricted product and insists on the production of a UK-issued passport or driving licence or other identity document, the supermarket would, in effect, be discriminating against this individual on this basis of his/her nationality in the provision of a service, thereby contravening the prohibition in Art 20(2) of Directive 2006/123/EC of discriminatory treatment relating to the nationality of a service recipient in the conditions of access to a service which are made available to the public at large by a service provider.[48]

On 11 June 2014, The Guardian published leaked internal documents from HM Passport Office in the UK which revealed that government officials who dealt with British passport applications sent from overseas treated EU citizen counter-signatories differently depending on their nationality. The leaked internal documents showed that for citizens of Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden who acted as a counter-signatory to support the application for a British passport made by someone whom they knew, HM Passport Office would be willing to accept a copy of the counter-signatory's passport or the national identity card.[49] HM Passport Office considered that national identity cards issued to citizens of these member states were acceptable taking into account the 'quality of the identity card design, the rigour of their issuing process, the relatively low level of documented abuse of such documents at UK/Schengen borders and our ability to access samples of such identity cards for comparison purposes'. In contrast, citizens of other EU member states (Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Romania and Spain) acting as counter-signatories could only submit a copy of their passport and not their national identity card to prove their identity as national identity cards issued by these member states were deemed by HM Passport Office to be less secure and more susceptible to fraud/forgery. The day following the revelations, on 12 June 2014, the Home Office and HM Passport Office withdrew the leaked internal guidance relating to EU citizen counter-signatories submitting a copy of their national identity card instead of their passport as proof of identity, and all EU citizen counter-signatories are now able only to submit a copy of their passport and not of their national identity card.[50][51]

In the UK, by law EU, EEA and Swiss citizens have an 'unlimited right to rent'.[52] However, landlords are legally obliged to check the immigration status of all prospective tenants before the start of a residential tenancy agreement (commonly known as a 'right to rent check').[53] According to the Right to Rent Document Checks User Guide issued by the Home Office, EU, EEA and Swiss citizens are entitled to produce a national identity card (current or expired) to satisfy this requirement. At the time, however, if the national identity card is not in English, the Home Office advises landlords that 'If in doubt, you can ask the tenant to provide other documents from the list in English. If you are not satisfied that they have the right to rent, you should not rent to them.'[54] In practice, this would affect some EU, EEA and Swiss citizens, as a number of member states (for example, France and Spain) issue national identity cards that do not contain English.

Common design and security features

On 13 July 2005, the Justice and Home Affairs Council called on all European Union member states to adopt common designs and security features for national identity cards by December 2005, with detailed standards being laid out as soon as possible thereafter.[55]

On 4 December 2006, all European Union member states agreed to adopt the following common designs and minimum security standards for national identity cards that were in the draft resolution of 15 November 2006:[56][57]

- Material

The card can be made with paper core that is laminated on both sides or made entirely of a synthetic substrate.

- Biographical data

The data on the card shall contain at least: name, birth date, nationality, a photo, signature, card number, and end date of validity.[58] Some cards contain more information such as height, eye colour, start date of validity, sex, issue place or province, and birth place.

The biographical data on the card is to be machine readable and follow the ICAO specification for machine-readable travel documents.

The EU Regulation revising the Schengen Borders Code (which entered into force on 7 April 2017 and introduced systematic checks of the travel documents of EU, EEA and Swiss citizens against relevant databases when entering and leaving the Schengen Area) states that all member states should phase out travel documents (including national identity cards) which are not machine-readable.[59]

However, as of 2017, Greece continues to issue solely non-machine readable identity cards, while Italy is in the process of phasing out the issuing of non-machine readable paper booklets in favour of biometric cards.

Electronic identity cards

All EEA electronic identity cards should comply with the ISO/IEC standard 14443. Effectively this means that all these cards should implement electromagnetic coupling between the card and the card reader and, if the specifications are followed, are only capable of being read from proximities of less than 0.1 metres.[60]

They are not the same as the RFID tags often seen in stores and attached to livestock. Neither will they work at the relatively large distances typically seen at US toll booths or automated border crossing channels.[61]

The same ICAO specifications adopted by nearly all European passport booklets (Basic Access Control - BAC) means that miscreants should not be able to read these cards[62] unless they also have physical access to the card.[63] BAC authentication keys derive from the three lines of data printed in the MRZ on the obverse of each TD1 format identity card that begins "I".

According to the ISO 14443 standard, wireless communication with the card reader can not start until the identity card's chip has transmitted a unique identifier. Theoretically an ingenious attacker who has managed to secrete multiple reading devices in a distributed array (eg in arrival hall furniture) could distinguish bearers of MROTDs without having access to the relevant chip files. In concert with other information, this attacker might then be able to produce profiles specific to a particular card and, consequently its bearer. Defence is a trivial task when most electronic cards make new and randomised UIDs during every session [NH08] to preserve a level of privacy more comparable with contact cards than commercial RFID tags.[64]

The electronic identity cards of Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Finland, Germany,[65] Italy, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Portugal and Spain all have a digital signature application which, upon activation, enables the bearer to authenticate the card using their confidential PIN. Consequently they can, at least theoretically, authenticate documents to satisfy any third party that the document's not been altered after being digitally signed. This application uses a registered certificate in conjunction with public/private key pairs so these enhanced cards do not necessarily have to participate in online transactions.[66]

An unknown number of national European identity cards are issued with different functionalities for authentication while online. Some also have an additional contact chip containing their electronic signature functionality, such as the Swedish national identity card.[64]

Portugal's card had an EMV application but it was removed in newer versions from 16 January 2016.[67][68]

New European Union rules

| European Union regulation | |

| Text with EEA relevance | |

| |

| Title | Regulation (EU) 2019/1157 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on strengthening the security of identity cards of Union citizens and of residence documents issued to Union citizens and their family members exercising their right of free movement |

|---|---|

| Made by | European Parliament and Council |

| Made under | Art. 21(2) TFEU |

| Journal reference | L 188, pp. 67–78 |

| History | |

| Date made | 20 June 2019 |

| Came into force | 10 July 2019 |

| Applies from | 2 August 2021 |

| Preparative texts | |

| Commission proposal | 17 April 2018 |

| Current legislation | |

Articles 3/4/5 of Regulation (EU) 2019/1157 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on strengthening the security of identity cards of Union citizens and of residence documents issued to Union citizens and their family members exercising their right of free movement, state:[69]

- Identity cards issued by Member States shall be produced in ID-1 format and shall contain a machine-readable zone (MRZ). Security standards shall be based on ICAO Document 9303. The document shall bear the title ‘Identity card’ in the official language and in at least one other official language of the institutions of the Union. It shall contain, on the front side, the two-letter country code of the Member State issuing the card, printed in negative in a blue rectangle and encircled by 12 yellow stars. It shall include a highly secure storage medium which shall contain a facial image of the holder of the card and two fingerprints in interoperable digital formats. The storage medium shall have sufficient capacity and capability to guarantee the integrity, the authenticity and the confidentiality of the data. The data stored shall be accessible in contactless form and secured as provided for in Implementing Decision C(2018) 7767.

- Identity cards shall have a minimum period of validity of 5 years and a maximum period of validity of 10 years. But Member States may provide for a period of validity of less than 5 years for minors and more than 10 years for persons aged 70 and above.

- Identity cards which do not meet the new requirements shall cease to be valid at their expiry or by 3 August 2031.

- Identity cards which do not meet the minimum security standards or which do not include a functional MRZ shall cease to be valid at their expiry or by 3 August 2026.

- Identity cards of persons aged 70 and above at 2 August 2021, which meet the minimum security standards and which have a functional MRZ shall cease to be valid at their expiry.

Article 16 states that this Regulation shall apply from 2 August 2021.

Overview of national identity cards

Member states issue a variety of national identity cards with differing technical specifications and according to differing issuing procedures.[70]

| Member state | Front | Reverse | Compulsory/optional | Cost | Validity | Issuing authority | Latest version |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Austria |

|

|

Identity documentation is optional |

|

|

3 May 2010 | |

Belgium |

Link to image | Link to image | National identity card compulsory for Belgian citizens aged 12 or over |

|

|

|

6 January 2020[71] |

Bulgaria |

|

|

National identity card compulsory for Bulgarian citizens aged 14 or over |

|

|

The police on behalf of the Ministry of the Interior. | 29 March 2010 |

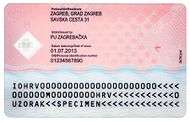

Croatia |

|

|

National identity card compulsory for Croatian citizens resident in Croatia aged 18 or over |

|

|

The police on behalf of the Ministry of the Interior.[73] | 8 June 2015 |

Cyprus |

|

|

National identity card compulsory for Cypriot citizens aged 12 or over |

|

|

24 February 2015 | |

Czech Republic |

|

|

National identity card compulsory for Czech citizens over 15 years of age with permanent residency in the Czech Republic |

|

|

municipality on behalf of the Ministry of the Interior | 19 May 2014 |

Denmark |

No national identity card of EU standard (See Identity document#Denmark). | Identity documentation is optional | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

Estonia |

Link to image | Link to image | National identity card compulsory for all Estonian citizens, permanent residents and EU/EEA citizens temporarily residing in Estonia aged 15 or over |

|

5 years | Police and Border Guard Board | 3 December 2018 |

Finland |

Link to image | Link to image | Identity documentation is optional |

Fees are lower if application is made online and if a passport application is done at the same time. |

5 years | Police | 1 January 2017[76] |

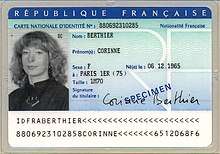

France |

|

|

Identity documentation is legally optional[77] but the police have extensive powers to check a person's identity in many situations, up to 4-hour detention to make the necessary verification and take a photograph.[78] |

|

|

|

1 October 1994 |

Germany |

Design until 01 August 2021  New design starting from 02 August 2021 |

|

National identity card optional; however, a national identity card or passport is compulsory for German citizens aged 16 or over, and valid identity documentation is compulsory for other EEA citizens |

|

|

|

1 November 2010 |

Gibraltar (United Kingdom) |

Identity documentation is optional | Free of charge |

|

Civil Status and Registration Office, Gibraltar, U.K. | 8 December 2000 | ||

Greece |

|

|

National identity card compulsory for Greek citizens aged 12 or over |

|

15 years | Police | 1 July 2010 |

Hungary |

|

|

National identity card optional; however, a national identity card, passport or driving licence is compulsory for Hungarian citizens aged 14 |

|

|

1 January 2016 | |

Iceland |

No national identity card. Icelandic state-issued identity cards and driver's licences do not state nationality and therefore are not usable as travel documentation outside of the Nordic countries. | Identity documentation compulsory for all persons. | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

Ireland |

Link to image | Link to image | Identity documentation is optional. An identity card called "passport card" exists as a card version of a passport. It is optional and can be purchased by Irish passport holders for easy identification and travel within the EEA[80][81]. In general drivers licences are used as identity cards locally. Public service cards can be used as identity for social welfare purposes. |

|

|

Passport Office, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade | 2 October 2015 |

Italy |

|

.png) |

National identity card optional, however, citizens should be able to prove their identity if stopped by territorial police |

|

|

Ministry of the Interior through: |

4 July 2016

|

Latvia |

Link to image | Link to image | National identity card optional; however, a national identity card or passport is compulsory for Latvian citizens aged 15 or over |

|

5 years | Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs | 2 September 2019 |

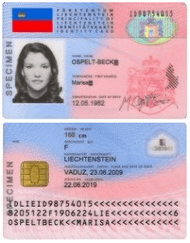

Liechtenstein |

Identity documentation is optional |

|

|

Immigration and Passport Office, Vaduz | 23 June 2008 | ||

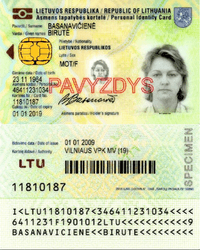

Lithuania |

Identity documentation is optional |

|

|

Police | 1 January 2009 | ||

Luxembourg |

Link to image | Link to image | National identity card compulsory for Luxembourgian citizens resident in Luxembourg aged 15 or over |

|

1 July 2014 [85] | ||

Malta |

Link to image | Link to image | National identity card compulsory for Maltese citizens aged 18 or over |

|

|

|

12 February 2014 |

Netherlands |

|

Link to image | National identity card optional;, however, valid identity documentation is compulsory for all persons aged 14 or over |

|

9 March 2014 | ||

Norway |

No national identity card currently; however, planned to be introduced in 2020.[90][91][92] [93] | Identity documentation is optional | Norwegian Police Service | 2020 | |||

Poland |

National identity card compulsory for Polish citizens resident in Poland aged 18 or over. | Free of charge |

|

City Office | 1 March 2019 | ||

Portugal |

|

|

National identity card (called "Citizen Card") compulsory for Portuguese citizens aged 6 or over |

|

|

Governos Civis | 1 June 2009 |

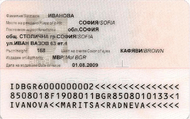

Romania |

Link to image | National identity card compulsory for Romanian citizens aged 14 or over with permanent residence in Romania | 12 RON to issue a new or a renewal card |

|

Ministry of Internal Affairs through the Directorate for Persons Record and Databases Management | 2 February 2017 | |

Slovakia |

National identity card compulsory for Slovak citizens aged 15 or over | Free of charge |

|

1 December 2013 | |||

Slovenia |

Link to image | Link to image | National identity card optional; however, a form of ID with photo is compulsory for Slovenian citizens permanently resident in Slovenia aged 18 or over |

|

|

|

20 June 1998 |

Spain |

Link to image | Link to image | National identity card compulsory for Spanish citizens aged 14 or over | €12 |

|

Police | 20 January 2016 |

Sweden |

Identity documentation is optional | SEK 400 | 5 years | Police | 2 January 2012 | ||

Switzerland |

Link to image | Link to image | Identity documentation is optional |

|

|

Federal Office of Police through canton / municipality of residence | 1 November 2005 |

United Kingdom |

No national identity card. See Identity document#United Kingdom. | Identity documentation is optional | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

See also

References

- ECB08: What are acceptable travel documents for entry clearance, UK Visas and Immigration. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- "Justisdepartementet: – Tipper nye ID-kort og pass kommer i 2020 | ABC Nyheter". 7 May 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Affairs, Department of Foreign. "New Passport Card - Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade".

- Travel documents for EU nationals, europa.eu. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- "Commission Staff Working Document - Impact Assessment accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation of the Euoprean Parliament of the Council on strengthening the security of identity cards of Union citizens and of residence documents issued to Union citizens and their family members exercising their right of free movement" (PDF). European Commission. 17 April 2018. p. 102.

As ID cards are less bulky and usually cheaper than passports, ID card ownership is much more widespread than passport ownership and tens of millions of journeys involving entry to the EU territory are made every year using ID cards.

- Articles 4 and 5 of the Citizens’ Rights Directive 2004/38/EC (L 158, pp. 77–123)

- Regulation 11 of the Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2016

- "Common Travel Area between Ireland and the United Kingdom". Citizensinformation.ie. Citizens Information Board. 1 February 2020.

- Article 5(4) of the Citizens’ Rights Directive 2004/38/EC (L 158, pp. 77–123)

- Practical Handbook for Border Guards, Part II, section I, point 2.9 (C (2019) 7131)

- Judgment of the European Court of Justice of 17 February 2005, Case C 215/03, Salah Oulane vs. Minister voor Vreemdelingenzaken en Integratie

- "Processing British and EEA Passengers without a valid Passport or Travel Document" (PDF).

- "Vize". Archived from the original on 6 August 2012.

- "VisitFaroeIslands - Living in the Faroe Islands". 21 May 2012. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "GeoConsul.Gov.Ge - Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia".

- "Special Categories Exempted From Visa Requirements - For Foreign Citizens - Consular Services - Ministry of Foreign Affairs - Republic of Kosovo".

- "Dropbox - Error" (PDF).

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 June 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Overview of visa regimes for foreign citizens".

- https://www.timaticweb.com/cgi-bin/tim_website_client.cgi?FullText=1&COUNTRY=MS&SECTION=pa&SUBSECTION=00&user=KLMB2C&subuser=KLMB2C

- "VISA Regulations - Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus".

- "Entry in the Republic of Macedonia for Schengen Visa Holders".

- "Consular countries".

- Lov om utlendingers adgang til riket og deres opphold her (utlendingsloven) kap 2 § 15 (Norwegian)

- "Frequently Asked Questions". 13 January 2016.

- "Visiting the UK: information for EU, EEA and Swiss citizens". GOV.UK. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "From Rep. of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs".

- http://www.ibz.rrn.fgov.be/fileadmin/user_upload/CI/eID/fr/acces_etranger/voyager_avec_des_documents_d_identite_belges.pdf

- International Ministère des Affaires étrangères et du Développement. "Egypte - Sécurité". diplomatie.gouv.fr.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Passlag (1978:302) (See 5§) (Swedish)

- Ökade möjligheter att resa inom EU med nationellt identitetskort (Swedish)

- "Regeländringar för att hantera brexit". Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Brexit - Storbritanniens utträde ur EU

- "FINLEX - Ursprungliga författningar: Statsrådets förordning om styrkande av rätten… 660/2013".

- "Commission Staff Working Document - Impact Assessment accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation of the Euoprean Parliament of the Council on strengthening the security of identity cards of Union citizens and of residence documents issued to Union citizens and their family members exercising their right of free movement" (PDF). European Commission. 17 April 2018. p. 12.

For instance Italian and Greek paper ID cards are frequently rejected at certain border checks (e.g. in UK, Germany and Spain). The fact that border control officials are not always familiar with the various identity documents in circulation can also result in more profound consequences, or at least, delays and inconvenience for citizens when exercising their right of free movement due to lengthy document checks.

- Home Office WI Checking Policy and operational instructions issued in June 2007 (see An inspection into border security checks, p. 21 by the Independent Chief Inspector of the UK Border Agency)

- Article 7(2) of the Schengen Borders Code in force until 6 April 2017(OJ L 105, 13 April 2006, p. 1). The amended Schengen Borders Code entered into effect on 7 April 2017: see Regulation (EU) 2017/458 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 amending Regulation (EU) 2016/399 as regards the reinforcement of checks against relevant databases at external borders (OJ L 74, 18 March 2017, p.1)

- Regulation (EU) 2017/458 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 amending Regulation (EU) 2016/399 as regards the reinforcement of checks against relevant databases at external borders (OJ L 74, 18 March 2017, p.1)

- See An Inspection of Border Force Operations at Stansted Airport, p. 12 by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration

- "Meeting of the User Experience Group of the Stansted Airport Consultative Committee, held at the Airport on 5 March 2014" (PDF). 11 June 2014. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- See An Inspection of Border Force Operations at Stansted Airport (table of statistics at 4.13 on p. 12) by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration

- "An Inspection of Juxtaposed Controls (November 2012 - March 2013)" (PDF). Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration. para 5.28. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "Commission Staff Working Document - Impact Assessment accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation of the Euoprean Parliament of the Council on strengthening the security of identity cards of Union citizens and of residence documents issued to Union citizens and their family members exercising their right of free movement" (PDF). European Commission. 17 April 2018. p. 14.

For instance, while Directive 2004/38 provides that EU citizens can travel between Member States on the basis of their ID cards, Italian citizens reported being advised by UK border officials to apply for a passport if they want to enter the UK the next time as the Italian ID card was "just a piece of paper", thus being confronted with obstacles to their free movement.

- "Guide to faster travel through the UK border". UK Border Force. 20 May 2019. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- See Risk Analysis for 2016 (table of statistics of fraudulent document detected, by main countries of issuance, 2015 on p. 24) by Frontex

- See Risk Analysis for 2017 (table of statistics of fraudulent document detected, by main countries of issuance, 2016 on p. 22) by Frontex

- "Answer to a written question - Validity of national ID cards - E-004933/2014".

- The Guardian: Passport Office briefing document (11 June 2014) Note that although the list included Switzerland, in practice Swiss citizens would not have been eligible to act as counter-signatories as they are not EU citizens.

- "Countersigning passport applications and photos - GOV.UK".

- Syal, Rajeev (11 June 2014). "Ministers intervene to prevent relaxation of checks at Passport Office" – via The Guardian.

- Immigration Act 2014, section 21

- Immigration Act 2014, section 22

- "Right to Rent Document Checks: a User Guide" (PDF). Home Office. December 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2020.

- "Council of the European Union: Draft Conclusions of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States on common minimum security standards for Member States' national identity cards" (PDF).

- "Council of the European Union: Draft Resolution of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States meeting within the Council on common minimum security standards for Member States' national identity cards" (PDF).

- "List of texts adopted by the Council in the JHA area – 2006" (PDF).

- "Machine Readable Travel Documents - Part 5" (PDF). ICAO. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- Recital 14 to Regulation (EU) 2017/458 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2017 amending Regulation (EU) 2016/399 as regards the reinforcement of checks against relevant databases at external borders (OJ L 74, 18 March 2017, p.1)

- "HM Government Guide" (PDF).

- "Grabba - MRZ Passport - Grabba".

- (DR), FIDISCoord. "D3.6: Study on ID Documents: Future of IDentity in the Information Society".

- Privacy Features of European eID Card Specifications Authors: Ingo Naumann, Giles Hogben of the European Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA), Technical Department P.O. Box 1309, 71001 Heraklion, Greece. This article originally appeared in the Elsevier Network Security Newsletter, August 2008, ISSN 1353-4858, pp. 9-13

- Helmbrecht, Udo; Naumann, Ingo (2011). "8: Overview of European Electronic Identity Cards". In Fumy, Walter; Paeschke, Manfred (eds.). Handbook of eID Security: Concepts, Practical Experiences, Technologies. II. John Wiley & Sons. p. 109. ISBN 978-3-89578-379-1.

- "Bundesdruckerei" (PDF).

- Helmbrecht, Udo; Naumann, Ingo (2011). "8: Overview of European Electronic Identity Cards". In Fumy, Walter; Paeschke, Manfred (eds.). Handbook of eID Security: Concepts, Practical Experiences, Technologies. II. John Wiley & Sons. p. 110. ISBN 978-3-89578-379-1.

- Sniffing with the Portuguese Identify (sic) Card for fun and Profit by Paul Crocker (Institute of Telecommunications, Covilhã, Portugal), Vasco Nicolau & Simão Melo de Sousa of the Universidade da Beira Interior. Conference paper presented at ECIW'2010 describes "a case study of the re-engineering process used to discover the low-level application protocol data units (APDUs) and their associated significance when used in communications with the Portuguese e-id smart card... primarily done simply to learn the processes involved given the low level of documentation available from the Portuguese government concerning the inner workings of the Citizens Card... also done in order to produce a generic platform for accessing and auditing the Portuguese Citizen Card and for using Match-on-Card biometrics for use in different scenarios... The Portuguese government rolled out a new electronic identity card ... called the "Cartão de Cidadão Português" produced by the "Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda" (INCM www.incm.pt). The initial concept of the card was to merge various identification documents into a single electronic smart card and permit the maximum of interoperability between the various entities whilst following Portuguese law." researchgate.net

- "Controlo do N.º de Versão, Cartão de Cidadão, REFERÊNCIA DOC 01-DCM-16 V3, 2016-01-20" (PDF). Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- "EUR-Lex - 32019R1157 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- State of play concerning the electronic identity cards in the EU Member States (COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, 2010)

- "Home". www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- https://gov.hr/moja-uprava/drzavljanstvo-i-isprave/isprave/osobna-iskaznica/296

- Zakon o osobnoj iskaznici Archived 8 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine (in Croatian)

- "Isikut tõendavad dokumendid".

- https://www.poliisi.fi/luvat/palveluhinnasto_ja_maksaminen/palveluhinnasto_2019

- https://www.consilium.europa.eu/prado/en/FIN-BO-09001/index.html

- "Est-il obligatoire d'avoir une carte d'identité ?". www.service-public.fr (in French). Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Contrôle d'identité". www.service-public.fr (in French). Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- Décret n° 2013-1188 du 18 décembre 2013 relatif à la durée de validité et aux conditions de délivrance et de renouvellement de la carte nationale d'identité, 18 December 2013, retrieved 9 November 2019

- PRADO - Public Register of Authentic travel and identity Documents Online, consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- FAQ - Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, dfa.ie.

- "Carta d'identità". www.esteri.it (in Italian). Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "La richiesta al Comune". Carta di identità elettronica (in Italian). Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "Circolare n. 7/2012 – Scadenza dei documenti di identità e di riconoscimento". Ministro per la Pubblica Amministrazione (in Italian). 20 July 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "Dan Kersch a présenté la nouvelle carte d'identité électronique - gouvernement.lu // L'actualité du gouvernement du Luxembourg".

- Haag, Den. "Nederlandse identiteitskaart".

- Haag, Den. "Paspoort en identiteitskaart voor Nederlanders in het buitenland". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- "Paspoort en identiteitskaart".

- "Identiteitskaart wordt 10 jaar geldig". Archived from the original on 21 January 2013.

- NRK. "Lover nasjonalt ID-kort i 2015".

- Nasjonalt ID-kort utsatt igjen (in Norwegian)

- "Politiet: Nye pass og nasjonale ID-kort kommer 1. april 2018 | ABC Nyheter". 5 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- Venter du på det nye nasjonale ID-kortet? Nå er det utsatt - igjen (dagbladet 26 aug 2017)