European Border and Coast Guard Agency

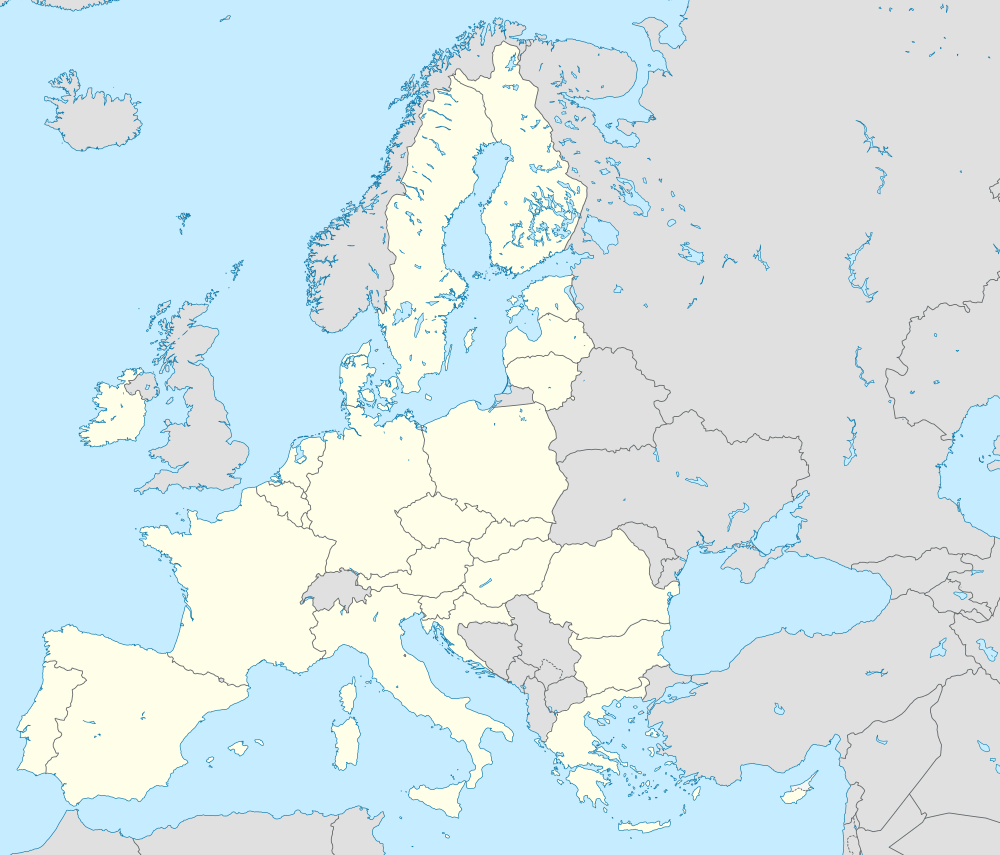

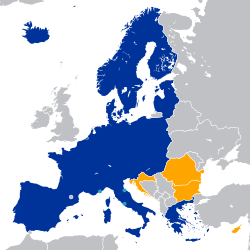

The European Border and Coast Guard Agency, also known as Frontex[5] (from French: Frontières extérieures for "external borders"), is an agency of the European Union headquartered in Warsaw, Poland, tasked with border control of the European Schengen Area, in coordination with the border and coast guards of Schengen Area member states.

The Warsaw Spire, housing Frontex's headquarters | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 6 October 2016 |

| Preceding Agency |

|

| Jurisdiction | European Union |

| Headquarters | Warsaw, Poland |

| Employees | 700 (2019)[1] 1,000 (2021, proposed)[1] 10,000 (2024/2027, proposed)[2][3][4] |

| Annual budget | € 420.6 million (2020)[2] |

| Agency executives |

|

| Key document | |

| Website | frontex |

| Map | |

Warsaw European Border and Coast Guard Agency (European Union) | |

.jpg)

Frontex was established in 2004 as the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders and is primarily responsible for coordinating border control efforts. In response to the European migrant crisis of 2015–2016, the European Commission proposed on 15 December 2015 to extend Frontex's mandate and to transform it into a fully-fledged European Border and Coast Guard Agency.[6] On 18 December 2015, the European Council roundly supported the proposal,[7] and after a vote by the European Parliament, the European Border and Coast Guard was officially launched on 6 October 2016 at the Bulgarian external border with Turkey.[8]

To enable the agency to carry out its tasks, its budget would be gradually increased from the €143 million originally planned for 2015 up to €238 million in 2016, €281 million in 2017, and will reach €322 million (about US$350 million) in 2020. The staff of the agency would gradually increase from 402 members in 2016 to 1,000 by 2020.[6]

History

2005–2016: European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders

Frontex, then officially the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders, was established by Council of Regulation (EC) 2007/2004.[9] It began work on 3 October 2005 and was the first EU agency to be based in one of the new EU member states from 2004. Frontex' mission is to help European Union member states implement EU rules on external border controls and to coordinate cooperation between member states in external border management. While it remains the task of each member state to control its own borders, Frontex is vested to ensure that they all do so with the same high standard of efficiency. The agency's main tasks according to the Council Regulation are:[9]

- coordinate cooperation between member states in external border management.

- assisting member states in training of national border guards.

- carrying out risk analyses.

- following research relevant for the control and surveillance of external borders.

- helping member states requiring technical and operational assistance at external borders.

- providing member states with the necessary support in organising joint return operations.

The institution was centrally and hierarchically organised with a management board, consisting of one person of each member state as well as two members of the Commission. The member states representatives are operational heads of national security services concerned with border guard management. Frontex also has representatives from and works closely with Europol and Interpol. The Management Board is the leading component of the agency, controlling the personal, financial, and organisational structure, as well as initiating operative tasks in annual work programmes. Additionally, the Board appoints the Executive Director. The first Director was Ilkka Laitinen.

The agency struggled to recruit staff[10] due to its location in Warsaw, which offered lower pay than some other cities, and the unclear agency mandate. According to its third amended Budget 2015, the agency had in that year 336 employees. Additionally it could make use of 78 employees which had been seconded from the member states.[11] The dependency of the organisation on staff secondments has been identified by external auditors as a risk, since valuable experience may be lost when such staff leave the organisation and return to their permanent jobs.[12]

Special European Border Forces of rapidly deployable border guards, called Rapid Border Intervention Teams (RABIT) who are armed and patrol cross-country land borders, were created by EU interior ministers in April 2007 to assist in border control, particularly on Europe's southern coastlines.[13] Frontex's European Patron Network began work in the Canary Islands in May 2007[14] and armed border force officers were deployed to the Greece–Turkey border in October 2010.[15]

2016–present: European Border and Coast Guard Agency

The Commission was prompted to take swift action due to the immigration crisis of 2015, which brought to the forefront the need to improve the security of the external borders of the union. This crisis has also demonstrated that Frontex, which had a limited mandate in supporting the Member States to secure their external borders, had insufficient staff and equipment, and lacked the authority to conduct border management operations and search-and-rescue efforts.

The new Agency was proposed by the European Commission on 15 December 2015[16] to strengthen Frontex, widely seen as being ineffective in the wake of the European migrant crisis. Support for the proposal has come from France and Germany, with Poland and Hungary expressing opposition to the plan, concerned by the perceived loss of sovereignty.[17]

The limitations of the former EU border agency, Frontex, hindered its ability to effectively address and remedy the situation created by the refugee crisis: it relied on the voluntary contributions by Member States as regards resources, it did not have its own operational staff, it was unable to carry out its own return or border management operations without the prior request of a Member State and it did not have an explicit mandate to conduct search and rescue operations. The enhanced Agency will be strengthened and reinforced to address all these issues. The legal grounds for the proposal are article 77, paragraph 2(b) and (d), and article 79, paragraph 2 (c), of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. Article 77 grants competence to the EU to adopt legislation on a "gradual introduction of an integrated management system for external borders," and article 79 authorizes the EU to enact legislation concerning the repatriation of third-country nationals residing illegally within the EU.

On 18 December 2015, the European Council roundly supported the proposal, which was then be subjected to the ordinary legislative procedure.[7] The Border and Coast Guard was officially launched on 6 October 2016 at the Bulgarian external border with Turkey.[8]

Organisation

According to the European Commission the European Border and Coast Guard "will bring together a European Border and Coast Guard Agency built from Frontex and the Member States’ authorities responsible for border management"[18] with day-to-day management of external border regions remaining the responsibility of member states. It is intended that the new European Border and Coast Guard Agency will act in a supporting role for members in need of assistance, as well as to coordinate overall border management of Europe's external borders. Securing and patrolling of the external borders of the European Union (EU, in practice the Schengen Area including the Schengen Associated Countries as well as those EU Member States which have not yet joined the Schengen Area but are bound to do so) is a shared responsibility of the Agency and the national authorities.

Agency

The European Border and Coast Guard Agency is not a new body. It does not replace Frontex and it retains the same legal personality. What the Commission draft Regulation aims to do is to strengthen the mandate of the EU border agency, to increase its competences and to better equip it to carry out its operational activities. The new tasks and responsibilities of the Agency need to be reflected by its new name.

.jpg)

It coordinates its work alongside the European Fisheries Control Agency and European Maritime Safety Agency with regard to coastguard functions.

The permanent staff of the Agency will be more than doubled between 2015 and 2020. The new proposal provides for a reserve of European border guards and technical equipment. The Agency will be able to purchase its own equipment (this is not a novelty). However - and this is new - the Member States where this equipment is registered (this refers mainly to big equipment items such as patrol vessels, air crafts, etc. which need a flag of state) will be obliged to put it at the Agency's disposal whenever needed. this will make it possible for the Agency to rapidly deploy the necessary technical equipment in border operations. A rapid reserve pool of border guards and a technical equipment pool will be put at the disposal of the agency, intending to remove the shortages of staff and equipment for the Agency's operations.

Monitoring and risk analysis

A monitoring and risk analysis centre will be established, with the authorisation to carry out risk analysis and to monitor the flows towards and within the EU. The risk analysis includes cross-border crime and terrorism, process personal data of persons suspected to be involved in acts of terrorism and cooperate with other Union agencies and international organisations on the prevention of terrorism. A mandatory vulnerability assessments of the capacities of the Member States to face current or upcoming challenges at their external borders will be established.

The Agency is able to launch joint operations, including the use of drones when necessary. The European Space Agency's earth observation system Copernicus provides the new Agency with almost real time satellite surveillance capabilities alongside the current Eurosur border surveillance system.

Teams

For joint operations and rapid border interventions, European Border and Coast Guard Teams can be established and deployed.

The right to intervene

When deficiencies in the functioning of the border management system of a Member State are identified as an outcome of the mandatory vulnerability assessment, the Agency will be empowered to require that Member States to take timely corrective action. In urgent situations that put the functioning of the Schengen area at risk or when deficiencies have not been remedied, the Agency will be able to step in to ensure that action is taken on the ground even where there is no request for assistance from the Member State concerned or where that Member State considers that there is no need for additional intervention.

The right to intervene. Member States will be able to request joint operations, rapid border interventions, and deployment of the EBCG Teams to support national authorities when a Member State experiences an influx of migrants that endangers the Schengen area. In such a case, especially when a Member State’s action is not sufficient to handle the crisis, the Commission will have the authority to adopt an implementing decision that will determine whether a situation at a particular section of the external borders requires urgent action at the EU level. Based on this decision, the EBCGA will be able to intervene and deploy EBCG Teams to ensure that action is taken on the ground, even when a Member State is unable or unwilling to take the necessary measures.

The right to intervene is a point of contention between a number of EU Members and the Commission, especially those Members whose borders form the external borders of the EU, such as Greece, Hungary, Italy, and Poland. They want to ensure that intervention is possible only with the consent of the Member States, whose external borders necessitate the presence of the EBCGA. Greece’s Alternate Minister for European Affairs, Nikos Xydakis, stated in an interview that while Greece is supportive of a common European action and of changing Frontex’s mandate, it wants the EBCGA to take complete charge of migration and refugee flows.

Working with and in third countries

The Agency has a new mandate to send liaison officers and launch joint operations with neighbouring third countries, including operating on their territory.

Repatriation of illegal immigrants

As part of the Border and Coast Guard a Return Office was established with the capacity to repatriate immigrants residing illegally in the union by deploying Return Intervention Teams composed of escorts, monitors, and specialists dealing with related technical aspects. For this repatriation, a uniform European travel document would ensure wider acceptance by third countries. In emergency situations such Intervention Teams will be sent to problem areas to bolster security, either at the request of a member state or at the agency's own initiative. It is this latter proposed capability, to be able to deploy specialists to member states borders without the approval of the national government in question that is proving the most controversial aspect of this European Commission plan.[6]

Risk analysis reports

Frontex regularly releases reports analyzing events related to border control, irregular border crossing and different forms of cross-border crime. The general task of assessing these risks has been laid out in Frontex founding regulation, according to which the agency shall "carry out risk analyses [...] in order to provide the Community and the Member States with adequate information to allow for appropriate measures to be taken or to tackle identified threats and risks with a view to improving the integrated management of external borders".[9] Frontex's key institution with respect to intelligence and risk assessment is its Risk Analysis Unit (RAU) and the Frontex Risk Analysis Network (FRAN), via which the Frontex staff is cooperating with security experts from the Member States.

The latest FRAN report as of 2013 stated that 24 805 illegal border-crossing were detected. In the Eastern Mediterranean area specifically at the land border between Greece and Turkey, illegal border-crossings were down by nearly 70% compared to the second quarter of 2012, but up in the Central Mediterranean route.[22]

Operations

Hermes

"Joint Operation Hermes" began on 20 February 2011, after Italy asked for Frontex surveillance of the Mediterranean Sea between Italy and North Africa, the southern border of the EU being in the Sea.[23] The Libyan no-fly zone came into effect subsequently, and combat operations started on 20 March 2011.

The Netherlands has a Coast Guard Dornier 228 aircraft with air force crew and Portugal, an air force C-295MPA, stationed at Malta and Pantelleria. The number of observed shiploads of people intending to illegally enter into the EU through this sector increased from 1,124 in the first quarter of 2013 to 5,311 in the second quarter of 2013.[24]

African and other would-be illegal immigrants continue to set sail for Italian shores aboard unseaworthy boats and ships. Several of these attempts have ended with capsized boats and hundreds of people drowning in the sea, though the Italian navy has saved thousands of lives in its Operation Mare Nostrum.[25]

Triton

Operation Triton is a border security operation conducted by Frontex, the European Union's border security agency. The operation, under Italian control, began on 1 November 2014 and involves voluntary contributions from 15 other European nations (both EU member states and non-members). Current voluntary contributors to Operation Triton are Croatia, Iceland, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, France, Spain, Ireland, Portugal, Austria, Switzerland, Romania, Poland, Lithuania, Malta and the United Kingdom.[26] The operation was undertaken after Italy ended Operation Mare Nostrum, which had become too costly for a single country to fund; it was costing the Italian government €9 million per month for an operation that lasted 12 months. The Italian government had requested additional funds from the other EU member states but they did not offer the requested support.[27]

"Joint Operation Triton" is under Italian control and focuses on border security within 30 nautical miles of the Italian shore. It began on 1 November 2014 and involves 15 other European nations volunteering services, both EU member states and non-members. As of 2015 voluntary contributors are Iceland, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, France, Spain, Portugal, Austria, Switzerland, Romania, Poland, Lithuania, Malta and the United Kingdom.[26] The operation's assets consist of two surveillance aircraft, three ships and seven teams of staff who gather intelligence and conduct screening and process identification. In 2014, its budget was estimated at €2.9 million per month.[28]

After the April 2015 Libya migrant shipwrecks, in which about 800 refugees died, EU ministers proposed on 20 April 2015, to double the size of Operation Triton and to widen its mandate to conduct search and rescue operations across the Mediterranean Sea.[29] Fabrice Leggeri, the head of Frontex, dismissed turning Triton into a search and rescue operation, saying it would "support and fuel the business of traffickers". Instead he recommended to expand air surveillance of the Maltese waters "anticipate more disasters.[30]

Moria Hotspot

On 12 December 2015 it was reported that a newly founded asylum seeker reception center in Moria, Lesbos, Greece was coordinated, controlled and monitored by Frontex. In this center, in prison-like conditions, the asylum seekers were reported to undergo swift detention about their status for the purposes of registration. Independent journalists were reported to have had limited access to the facilities. While the reception center is not in the position to grant refugee status, it was reported that some asylum seekers could be held in the reception camp indefinitely.[31]

Poseidon

"Joint Operation Poseidon" began on 2006, after Greece asked for surveillance by Frontex of the country's sea and land borders between the EU-member Greece and Turkey. The Joint Operation is divided into two branches, the Poseidon Sea Operation which oversees the sea borders of the EU with Turkey in the Mediterranean and Aegean seas,[32] and the Poseidon Land Operation which oversees the southeastern land border of the EU with Turkey on the Evros river.[33] The operation turned permanent and has been expanded subsequently on the year 2011. In 2015 this operation was replaced by Poseidon Rapid Intervention.[34]

Controversies

Alleged Turkish airspace violations

In September 2009, a Turkish military radar issued a warning to a Latvian helicopter patrolling in the eastern Aegean—part of the EU's Frontex programme to combat illegal immigration—to leave the area. The Turkish General Staff reported that the Latvian Frontex aircraft had violated Turkish airspace west of Didim.[35] According to a Hellenic Air Force announcement, the incident occurred as the Frontex helicopter—identified as an Italian-made Agusta A109—was patrolling in Greek airspace near the small isle of Farmakonisi, which lies on a favourite route used by migrant smugglers ferrying migrants into Greece and the EU from the opposite Turkish coastline.[36] Frontex officials stated that they simply ignored the Turkish warnings as they were not in Turkish airspace and continued their duties. Frontex later took photographs of the Turkish Coast Guard escorting illegal immigrants towards Greek waters and the photos accompanied by written evidence were submitted to EU authorities.[37]

Another incident took place on October 2009 in the airspace above the eastern Aegean sea, off the island of Lesbos.[38] On 20 November 2009, the Turkish General Staff issued a press note alleging that an Estonian Border Guard aircraft Let L-410 UVP taking off from Kos on a Frontex mission had violated Turkish airspace west of Söke.[35]

Criticism

In an NGO Statement on International Protection[39] presented at the UNHCR Standing Committee in 2008 a broad coalition of non-governmental organisations have expressed their concern, that much of the rescue work by Frontex is in fact incidental to a deterrence campaign so broad and, at times, so undiscriminating, that directly and through third countries – intentionally or not – asylum-seekers are being blocked from claiming protection under the 1951 Refugee Convention.

According to European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE) and British Refugee Council in written evidence submitted to the UK House of Lords inquiry, Frontex fails to demonstrate adequate consideration of international and European asylum and human rights law including the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and EU law in respect of access to asylum and the prohibition of refoulement.[40]

In addition ECRE and British Refugee Council have expressed a worry with the lack of clarity regarding Frontex accountability for ensuring compliance with international and EC legal obligations by Member States involved in Frontex coordinated operations. This is compounded by the lack of transparency, and the absence of independent monitoring and democratic accountability of the Agency.

European Border and Coast Guard

The European Border and Coast Guard is formed by the Frontex agency itself and by the border guards and coast guards of the Schengen Area member states. The national authorities will continue to exercise the day-to-day management of their sections of the external borders of the Schengen Area. They are:

See also

- Schengen Area

- Common Security and Defence Policy

- Area of freedom, security and justice

- Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters

- European Asylum Curriculum

- Asylum in the European Union

- Schengen Agreement

- Global Monitoring for Environment and Security ('Copernicus Programme')

- External border of the European Union

References

- "Frontex Careers General Information". Frontex. Frontex. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "EU budget 2020". European Commission. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Opening Statement in the European Parliament Plenary Session by Ursula von der Leyen, Candidate for President of the European Commission". European Commission. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "European Border and Coast Guard - Press release". European Commission. European Commission. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- See Regulation (EU) 2016/1624 recital 11 ("...the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union should therefore be expanded. To reflect those changes, it should be renamed the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, which will continue to be commonly referred to as Frontex. It should remain the same legal person, with full continuity in all its activities and procedures....") and article 6 ("The European Border and Coast Guard Agency shall be the new name for the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Members States of the European Union established by Regulation (EC) No 2007/2004. Its activities shall be based on this Regulation....")

- "European Agenda on Migration: Securing Europe's External Borders". europa.eu. European Commission. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- "Subscribe to read". Financial Times.

- "News". European Commission - European Commission.

- "Council Regulation 2004 (EC) No 2007/2004". Council of the European Union. 2004-10-26. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- "BBC NEWS - Europe - Staff woes hit EU border agency". 2007-01-26.

- "Frontex Amended Budget 2015 N3 - 06.11.2015" (PDF). Archived from the original on December 18, 2016. Retrieved 2016-12-18.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "External evaluation of the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union". Cowi. January 2009. Retrieved 2012-02-12.

- EU agrees rapid reaction anti-immigration units euobserver.com

- EU border agency starts sea patrols euobserver.com

- Pop, Valentina. "/ Justice & Home Affairs / EU to deploy armed patrols at Greek-Turkish border". Euobserver.com. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- "A European Border and Coast Guard to protect Europe's External Borders". European Commission. 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-15.

- "Migrant crisis: EU to launch new border force plan". BBC News. 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-15.

- "A European Border and Coast Guard to protect Europe's External Borders". europa.eu. European Commission. 15 December 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- Peers, Steve (October 8, 2018). "EU Law Analysis: The next phase of the European Border and Coast Guard: towards operational effectiveness".

- "Frontex budget". February 11, 2019.

- Frontex (12 June 2019). "Consolidated Annual Activity Report 2018" (PDF). p. 78. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Annual Risk Analysis". Frontex. 2012-05-19. Retrieved 2012-06-01.

- "Frontex begins Operation Hermes in Lampedusa following request from Italy. Boundary news, International Boundaries Research Unit at Durham University, NC, USA". Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- "Frontex Quarterly Report FRAN Quarterly Quarter 2, April–June 2013". frontex.europa.eu. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- Gavin Jones Italy says two boat migrants die, 1,500 saved as total passes 100,000 Reuters UK, 15 August 2015

- "Frontex Triton operation to 'support' Italy's Mare Nostrum". ANSA. 2014-10-16. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- "Italy Is About to Shut Down the Sea Rescue Operation That Saved More Than 90,000 Migrants This Year". VICE News. 2014-10-03. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- "EC MEMO, Brussels, 7 October 2014, Frontex Joint Operation 'Triton' – Concerted efforts to manage migration in the Central Mediterranean". European Union, European Commission. 7 October 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- "Migrants' bodies brought ashore as EU proposes doubling rescue effort". Reuters. 20 April 2015.

- Patrick Kingsley, Ian Traynor (22 April 2015). "EU borders chief says saving migrants' lives 'shouldn't be priority' for patrols". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- "Hotspots für Flüchtlinge: Das hässliche Gesicht Deutschlands und der EU". DEUTSCHE WIRTSCHAFTS NACHRICHTEN. 12 December 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "Frontex - Archive of operations - Poseidon Sea". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "Frontex Mission in Greece Turns Permanent, Expanded to Bulgaria-Turkey Border". Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- "Frontex - News - Frontex launches rapid operational assistance in Greece". Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- Türk Silahlı Kuvvetleri - Turkish Armed Forces "Airspace violations in the Aegean". Archived from the original on 2010-03-12.

- "Latest Frontex patrol harassed" (in Greek). Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Nick Iliev (2009-09-21). "Turkish coast guard caught escorting smugglers into Greece - report - South Eastern Europe". The Sofia Echo. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- "Newest Frontex patrol harassed". Troktiko Blogspot. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- "NGO Statement on International Protection: The High Commissioner's Dialogue on Protection Challenges" (PDF). UNHCR. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- "ECRE/BRC joint response to House of Lords inquiry on Frontex". ECRE. Archived from the original on 2014-11-05. Retrieved 2009-06-11.