Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

Lunenburg is a port town on the South Shore of Nova Scotia, Canada. Founded in 1753, the town was one of the first British attempts to settle Protestants in Nova Scotia in an effort to displace the French colonial Roman Catholic Acadians and indigenous Mi'kmaq.

Lunenburg | |

|---|---|

Aerial photo of Lunenburg | |

Seal | |

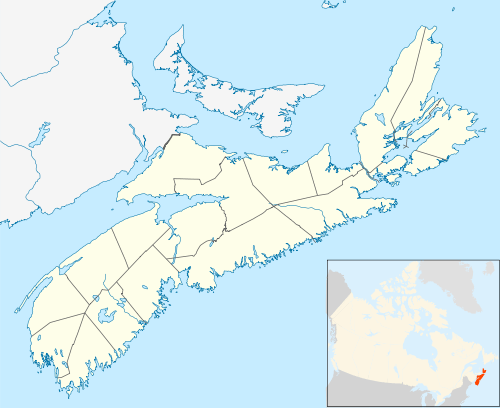

Lunenburg Location of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia | |

| Coordinates: 44°23′N 64°19′W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| County | Lunenburg |

| Founded | 1753 |

| Incorporated | October 31, 1888 |

| Electoral Districts Federal | South Shore—St. Margarets |

| Provincial | Lunenburg |

| Government | |

| • Body | Lunenburg Town Council |

| • Mayor | Rachel Bailey |

| • MLA | Suzanne Lohnes-Croft (L) |

| • MP | Bernadette Jordan (L) |

| Area (2016)[1] | |

| • Land | 4.04 km2 (1.56 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[1] | |

| • Total | 2,263 |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (AST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−3 (ADT) |

| Postal code | B0J |

| Area code(s) | 902 & 782 |

| Highways | |

| Website | Town of Lunenburg |

| Official name | Old Town Lunenburg |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv, v |

| Designated | 1995 (19th session) |

| Reference no. | 741 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Official name | Old Town Lunenburg Historic District National Historic Site of Canada |

| Designated | 1991 |

| Type | Heritage Conservation District |

| Designated | 2000 |

The economy was traditionally based on the offshore fishery and today Lunenburg is the site of Canada's largest secondary fish-processing plant. The town flourished in the late 1800s, and much of the historic architecture dates from that period.

In 1995 UNESCO designated it a World Heritage Site. UNESCO considers the site the best example of planned British colonial settlement in North America, as it retains its original layout and appearance of the 1800s, including local wooden vernacular architecture. UNESCO considers the town in need of protection because the future of its traditional economic underpinnings, the Atlantic fishery, is now very uncertain.

The historic core of the town is also a National Historic Site of Canada.[2]

Toponymy

Lunenburg was named in 1753 after the Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg who had become King George II of Great Britain.[3] The displaced Acadian inhabitants of the site had called it Mirliguèche, a French spelling of a Mi'kmaq name[4] of uncertain meaning. An earlier Mi'kmaq name was āseedĭk, meaning clam-land.[5]

History

The Mi'kmaq lived in a territory from the present site of Lunenburg to Mahone Bay. As many as 300 inhabited the site in the warm summer months.[6] French colonists, who became known as Acadians, settled in the area around the 1620s. The Acadians and Mi’kmaq lived peacefully and some intermarried, creating networks of trade and kinship. In 1688, 10 Acadians and 11 Mi’kmaq were resident with dwellings and a small area of cultivated land. By 1745 there were eight families.

When Edward Cornwallis, newly appointed Governor of Nova Scotia, visited in 1749, he reported several Mi’kmaq and Acadian families living together at Mirliguèche in comfortable houses and said they appeared to be doing well.[7]

Britain and France carried their military action in Europe in the 1700s to the New World. Under the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, France ceded the part of Acadia today known as peninsular Nova Scotia to Britain. But the inhabitants of the area did not welcome the new regime. To guard against Mi'kmaq, Acadian and colonial French attacks, the British erected Fort George in 1749 at Citadel Hill Halifax and founded the town of Halifax. Later that year, Cornwallis ordered Mirliguèche destroyed.

The British sought to settle the lands with loyal subjects, and recruited more than 1,400 foreign Protestants, mostly artisans and farmers, from Europe in July 1753 to populate the site. Led by Charles Lawrence,[8] the settlers were accompanied by about 160 soldiers. They assembled prefabricated blockhouses and built a palisade along the neck of land where the village was laid out.[9] The settlers spent the summer building shelters for the winter[10] and, not having been able to conduct any fishing or farming, had to be provisioned from Halifax.[11] When the settlers became dissatisfied with the distribution of provisions, they rose in armed rebellion, only to be put down by troops led by Colonel Robert Monckton.[12] Others defected to the Acadian side.[13] In 1754 the town had a sawmill and a store.[14]

In 1755, after the expulsion of the Acadians, the British needed to repopulate vacated lands. It offered generous land grants to colonists from New England, which was experience a severe land shortage.[15] Today these immigrants are known as the New England Planters, planters being an old word for colonist. Lunenburg was raided in 1756 by Mi'kmaq and allies, and afterwards.[16] The British responded with the Lunenburg Campaign of 1758. Hostilities with Mi'kmaq ended around 1760.

During the American Revolution, privateers from the colonies raided Lunenburg, including the 1782 raid, devastating the town. The town was fortified at the beginning of the War of 1812.[17] The British officials authorised the privateer Lunenburg, operated by Lunenburg residents, to raid United States American shipping.[18]

Over the following years, port activities transitioned from coastal trade and local mixed fisheries,[19] to offshore fisheries. During the Prohibition in the United States between 1920 and 1933 in the United States, Lunenburg was a base for rum-running to the US.[20]

The Lunenburg Cure was the term for a style of dried and salted cod that the city exported to markets in the Caribbean.[21] Today a large hammered copper cod weather vane is mounted on the spire of St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church.

The Smith & Rhuland shipyard built many boats, including Bluenose (1921), Flora Alberta (1941), Sherman Zwicker (1942), Bluenose II (1963), Bounty (1961), and the replica HMS Surprise (1970). In 1967 the yard was taken over by Scotia Trawler Equipment Limited. After the end of World War II, shipbuilders switched from producing schooners to trawlers, aided by migrant labour from Newfoundland.[22]

Geography

Physical geography

Lunenburg is in a natural harbour at the western side of Mahone Bay, about 100 kilometres southwest of the Halifax Regional Municipality.

The area is built largely on Cambrian to Ordovician sedimentary deposits. The last glacial period transformed the landscape. Glaciers abraded and plucked at the bedrock during their advances across the country, creating various deposits that vary in thickness, including drumlins, which are a key feature of Lunenburg County.[23]

The coastline in the area is heavily indented, and the town is on an isthmus on the Fairhaven Peninsula, with harbours on both the front and back sides.

Climate

The climate of Lunenburg is humid continental, bordering on an oceanic, with warm summers and mild winters, due to Gulf Stream moderation, which also causes seasonal lag. Generally Lunenburg is cool and rather wet. The average temperature is 6.5 °C. Even the driest month, July, sees 85 mm of rain, while the wettest, December, sees 149 mm. August is the warmest month, with an average temperature of 17.1 °C. February is the coldest with -4.4 C on average.[24]

Old Town

The original planned town was built on a steep south-facing hillside. It was laid out with compact lots in a rectangular grid pattern of narrow streets without regard to the topography.[25] It is now known as the Old Town, and is the part of town which is protected by UNESCO. It is also the site of the old harbour. About 40 buildings in this area are on the Canadian Register of Historic Places including:

- Knaut-Rhuland House, 1793:[26] Now a museum run by the Lunenburg Heritage Society.[27]

- Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church, 1890: large wooden church.[28]

- St. John's Anglican Church, 1763: large wooden Carpenter Gothic church.[29]

The Lunenburg Opera House is also in this area, though built in 1909, and not on the registry.

In 2005 the province of Nova Scotia bought 17 waterfront buildings from Clearwater Foods, the owner of the High Liner Foods brand, to ensure their preservation.[30] Ownership was transferred to the Lunenburg Waterfront Association. Shipbuilding infrastructure worth $1.5 million was added to the Lunenburg waterfront as part of the Bluenose II restoration project, which started in 2010.[31]

The site of the Smith & Rhuland shipyard is now a recreational marina.

The Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic, part of the Nova Scotia Museum, includes a small fleet of vessels,[32] including Bluenose II.[33]

Parts of the waterfront are still used by business. The shipyard ABCO Industries was founded in 1947 on the site of the World War II Norwegian military training facility Camp Norway, and now builds welded aluminum vessels. Lunenburg Shipyard is owned and operated by Lunenburg Industrial Foundry & Engineering. It offers a dry dock, manufacturing and machining, a carpentry shop, and a foundry capable of pouring 272 kg castings.[34] There are wharves for commercial inshore fishing.

New Town

In the 1800s Lunenburg prospered through shipping, trade, fishing, farming, shipbuilding, and outgrew its original boundaries. The town was extended into the east and west of the Old Town into what is now known as the New Town.[35] This area includes about a dozen buildings on the Canadian Register of Historic Places.

Governance

Government in Nova Scotia has only two tiers: provincial and municipal. The province is divided into 50 municipalities, of which Lunenburg is one. The town is also within Lunenburg County, which was created for court sessional purposes in the 1860s and today has no government of its own, but the borders of which are coincident with certain provincial and federal electoral districts such as the Lunenburg Provincial Electoral District, and census districts. The county also covers the same terrain as the Municipality of the District of Lunenburg which surrounds, but does not include, Bridgewater, Lunenburg, and Mahone Bay, as they are incorporated separately and not part of the district municipality.

Economy

According to the 2016 census the most common National Occupational Classification was sales and services, with 24 per cent of jobs. By the North American Industry Classification System about half of all jobs were in health care and social assistance, accommodation and food services, manufacturing, and retail.[1] High Liner Foods runs Canada's largest secondary fish-processing plant in the town.[36]

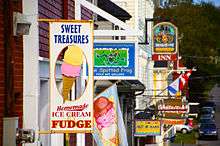

The town's architecture and picturesque location make it attractive to the film industry.[36] Films set in New England but filmed partly in Lunenburg include The Covenant[37] and Dolores Claiborne.[38] The 2010 Japanese movie Hanamizuki was partly set and filmed in Lunenburg[39] and the science fiction television show Haven was partly filmed there though it is set in the United States.[40] The 2012 film The Disappeared and the 2020 television series Locke & Key were filmed in Lunenburg.[41][42]

Demographics

The population of Lunenburg has varied between two and three thousand since 1871, peaking from the 1960s to the '80s, and declining since. In the 2016 Census conducted by Statistics Canada, the Town of Lunenburg recorded a population of 2,263 living in 1,040 of its 1,206 total private dwellings, a change of -2.2% from its 2011 population of 2,313. The overwhelming majority of the population is English-speaking Canadian Protestants. The population decreased slightly from 2011 to 2016, while Nova Scotia's population increased slightly. At 58, the median age is higher than the provincial median of 46. Household incomes are similar to provincial averages.[1] With a land area of 4.04 km2 (1.56 sq mi), Lunenburg had a population density of 560.1/km2 (1,450.8/sq mi) in 2016.[1]

Gallery

St. John's Anglican Church, Lunenburg – built during the war (1754-1763)

St. John's Anglican Church, Lunenburg – built during the war (1754-1763) Raid on Lunenburg (1756) by Donald A. Mackay

Raid on Lunenburg (1756) by Donald A. Mackay Raid on Lunenburg (1782) by A. J. Wright

Raid on Lunenburg (1782) by A. J. Wright Lunenburg as seen from Common Range in the 1880s

Lunenburg as seen from Common Range in the 1880s- Memorial to fishermen along Bluenose Drive. Unveiled on August 25, 1996.

Lunenburg's World War I memorial

Lunenburg's World War I memorial Town of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia looking across Lunenburg Harbour from the Bluenose Golf course

Town of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia looking across Lunenburg Harbour from the Bluenose Golf course Lunenburg Harbour

Lunenburg Harbour Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic

Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic Lunenburg Boat Yards

Lunenburg Boat Yards Bluenose II in Lunenburg

Bluenose II in Lunenburg View of Waterfront

View of Waterfront Lunenburg Academy

Lunenburg Academy- Knaut-Rhuland House Museum

Lunenburg House

Lunenburg House Zion Lutheran Church

Zion Lutheran Church Tourists enjoy a carriage ride through the historic district of Lunenburg. The landscape is dominated by rolling drumlins—a consistent feature of the region.

Tourists enjoy a carriage ride through the historic district of Lunenburg. The landscape is dominated by rolling drumlins—a consistent feature of the region.

See also

- Lunenburg English

- Charles Morris: surveyor who laid out Halifax, Lunenburg, Lawrencetown, and Liverpool.[43]

- Dettlieb Christopher Jessen: first member of the house of assembly for the town.[44]

- John Creighton: early settler and politician.[45]

- Jean-Baptiste Moreau: first missionary at the site[46]

- Halifax and South Western Railway: former railway line that served the South Shore.[47]

References

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data (Nova Scotia)". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- Old Town Lunenburg Historic District National Historic Site of Canada. . Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- "Lunenburg". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Beck, Lauren (2016). "Early-Modern European and Indigenous Linguistic Influences on New Brunswick Place Names". Journal of New Brunswick Studies (7): 26. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Rand, Silas (1875). A First Reading Book in the Micmac Language: Comprising the Micmac Numerals, and the Names of the Different Kinds of Beasts, Birds, Fishes, Trees, &c. of the Maritime Provinces of Canada. Also, Some of the Indian Names of Places, and Many Familiar Words and Phrases, Translated Literally Into English. Nova Scotia Printing Company. p. 91. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Wicken, Bill (1993). "26 August 1726: A Case Study in Mi'kmaq-New England Relations in the Early 18th Century". Acadiensis. XXIII (Autumn): 5–22. JSTOR 30303468.

- Knickle, Margaret JA (2017). Creating Space for Historical Narratives Through Indigenous Storywork and Unsettling the Settler (PDF). Mount Saint Vincent University. p. 59. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Graham, Dominick (1974–2019). "Charles Lawrence". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Ferguson, Charles (1974–2019). "Patrick Sutherland". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 11 May 2019.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Genier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0806138763. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604–1755. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 422. ISBN 978-0773526990. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Murdoch, Beamish (1866). A History of Nova Scotia, Or Acadie. J Barnes. p. 227. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Beck, J (1979–2019). "Philip Augustus Knaut". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "The Population Explosion in 1700s America". dummies. Wiley. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Bell, Winthrop (1961). The Foreign Protestants and the Settlement of Nova Scotia: The History of a Piece of Arrested British Colonial Policy in the Eighteenth Century. University of Toronto Press. p. 513. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Young, Richard. "Blockhouses in Canada, 1749–1841: A Comparative Report and Catalogue". Parks Canada. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Boileau, John (2005). Half-Hearted Enemies: Nova Scotia, New England and the War of 1812. Formac Publishing Company. p. 66. ISBN 9780887806575. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- "Fishery". Canadian Geographic. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- "Recalling cops and rum runners in Prohibition". CBC. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Kurlansky, Mark (1998). Cod : A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World. Vintage Canada. p. 128. ISBN 978-0676971118. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Neary, Peter (1982). "Canadian Immigration Policy and the Newfoundlanders, 1912–1939". Acadiensis. pp. 78–83.

- Roland, Albert (1982). Geological Background and Physiography of Nova Scotia. Halifax, N.S.: Ford Publishing Co. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-919680-19-7.

- "Lunenburg". climate-data.org. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- "18th Century". Town of Lunenburg. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Knaut-Rhuland House. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 07 May 2019.

- "Knaut-Rhuland House Museum, National Historic Site". Lunenburg Heritage Society. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 04 May 2019.

- St. John's Anglican Church. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 04 May 2019.

- Dunfield, Allison. "Nova Scotia to buy historic Lunenburg buildings". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Restoration of Bluenose II to begin". CBC. 2010. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "Vessels". Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic. Nova Scotia Museum. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Bluenose II". novascotia.ca. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "Lunenburg Industrial Foundry & Engineering". Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "19th Century". Town of Lunenburg. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Mccann, L (2015). "Lunenburg". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "The Covenant (2006)". IMDB. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Dolores Claiborne (1995)". IMDB. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "5 Months in Total After the Start of Filming in Canada..." The Japan Times Online (in Japanese). cafegroove Corporation. 2010-04-27. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- "Haven (2010–2015)". IMDB. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Behind-the-scenes look at local movie shoot: The Disappeared" (PDF). The Lunenburg County Progress. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- Blakely, Phyllis (1979–2019). "Charles Morris". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Beck, J (1983–2019). "Christopher Dettlieb Jessen". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Lava. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Beck, J (1983–2019). "John Creighton". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Fingard, Judith (1974–2019). "Jean-Baptiste Moreau". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "Welcome To The H & SW Railway Museum". Halifax & Southwestern Railway Museum. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lunenburg. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lunenburg. |