Law and Justice

Law and Justice (Polish: Prawo i Sprawiedliwość [ˈpravɔ i spravjɛdˈlivɔɕtɕ] (![]()

The party was founded in 2001 by the Kaczyński twins, Lech and Jarosław, as a centrist and Christian democratic party. It was formed from part of the Solidarity Electoral Action (AWS), with the Christian democratic Centre Agreement forming the new party's core.[43] The party won the 2005 election, while Lech Kaczyński won the presidency. Law and Justice formed coalition with the Eurosceptic League of Polish Families (LPR) and Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland (SRP). Jarosław served as Prime Minister, before calling elections in 2007, in which the party came in second to Civic Platform (PO). In these elections PiS lost most of its moderate electorate but attracted voters from its former coalition members and then turned to nationalism and populism. As a result LPR and SRP lost all their seats and descended into political irrelevancy. Several leading members, including sitting president Lech Kaczyński, died in a plane crash in 2010.

During its founding the party was dominated by the Kaczyńskis' conservative and law and order agenda.[43] It has embraced economic interventionism, while maintaining a socially conservative stance that in 2005 moved towards the Catholic Church;[43] the party's Catholic-nationalist wing split off in 2011 to form Solidary Poland but then formed a joint ballot with PiS before the 2015 elections. The party is solidarist and mildly Eurosceptic, and shares similar political tactics with Hungary's Fidesz but with anti-Russian stances.

History

Formation

The party was created on a wave of popularity gained by late president of Poland Lech Kaczyński while heading the Polish Ministry of Justice (June 2000 to July 2001) in the AWS-led government, although local committees began appearing from 22 March 2001. The AWS itself was created from a diverse array of many small political parties.

In the 2001 general election, PiS gained 44 (of 460) seats in the lower chamber of the Polish Parliament (Sejm) with 9.5% of votes. In 2002, Lech Kaczyński was elected mayor of Warsaw. He handed the party leadership to his twin brother in 2003.

In coalition government: 2005–2007

In the 2005 general election, PiS took first place with 27.0% of votes, which gave it 155 out of 460 seats in the Sejm and 49 out of 100 seats in the Senate. It was almost universally expected that the two largest parties, PiS and Civic Platform (PO), would form a coalition government.[43] The putative coalition parties had a falling out, however, related to a fierce contest for the Polish presidency. In the end, Lech Kaczyński won the second round of the presidential election on 23 October 2005 with 54.0% of the vote, ahead of Donald Tusk, the PO candidate.

After the 2005 elections, Jarosław should have become Prime Minister. However, in order to improve his brother's chances of winning the presidential election (the first round of which was scheduled two weeks after the parliamentary election), PiS formed a minority government headed by Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz as prime minister, an arrangement that eventually turned out to be unworkable. In July 2006, PiS formed a right-wing coalition government with the agrarian populist Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland and the nationalist League of Polish Families, headed by Jarosław Kaczyński. Association with these parties, on the margins of Polish politics, severely affected the reputation of PiS. When accusations of corruption and sexual harassment against Andrzej Lepper, the leader of Self-Defence, surfaced, PiS chose to end the coalition and called for new elections.

In opposition: 2007–2015

.jpg)

In the 2007 general election, PiS managed to secure 32.1% of votes. Although an improvement over its showing from 2005, the results were nevertheless a defeat for the party, as Civic Platform (PO) gathered 41.5%. The party won 166 out of 460 seats in the Sejm and 39 seats in Poland's Senate.

On 10 April 2010, its former leader Lech Kaczyński died in the 2010 Polish Air Force Tu-154 crash. Jarosław Kaczyński becomes the sole leader of the party. He was the presidential candidate in the 2010 elections.

In majority government: 2015–present

The party won the 2015 parliamentary election, this time with an outright majority—something no Polish party had done since the fall of Communism. In the normal course of events, this should have made Jarosław Kaczyński prime minister for a second time. However, Beata Szydło, perceived as being somewhat more moderate than Kaczyński, had been tapped as PiS' candidate for prime minister.[44][45]

The Law and Justice government has been accused of posing a threat to the Polish liberal democratic system by majority of opposition groups.[46][47][48][49][50][51][52] PiS' 2015 victory prompted creation of a cross-party opposition movement, the Committee for the Defence of Democracy (KOD). Law and Justice has supported controversial reforms carried out by the Hungarian Fidesz party, with Jarosław Kaczyński declaring in 2011 that "a day will come when we have a Budapest in Warsaw".[53] Proposed 2017 judicial reforms, which according to the party were meant to improve efficiency of the justice system, sparked protest as they were seen as undermining judicial independence.[54][55][56][57][58] As of December 2017, the draft bill is being amended following a veto from President Andrzej Duda.

Law and Justice has been accused by The Economist for undermining democracy and the rule of law and promoting right-wing extremism.[59] However, it still enjoys support from many within the country, as some see it as a force that restored rule of law after the perceived corruption of Civic Platform, exemplified for instance by the inability of the Civic Platform's government to properly gather VAT taxes as well as its politicians being involved in the reprivatization scandal in Warsaw.[60][61]

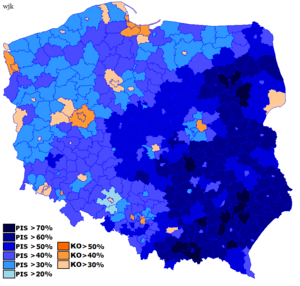

The party won reelection in the 2019 parliamentary election. With 44% of the popular vote, Law and Justice received the highest vote share by any party since Poland returned to democracy in 1989, but lost its majority in the Senate.

Breakaways

In January 2010, a breakaway faction led by Jerzy Polaczek split from the party to form Poland Plus. Its seven members of the Sejm came from the centrist, economically liberal wing of the party. On 24 September 2010, the group was disbanded, with most of its Sejm members, including Polaczek, returning to Law and Justice.

On 16 November 2010, MPs Joanna Kluzik-Rostkowska, Elżbieta Jakubiak and Paweł Poncyljusz, and MEPs Adam Bielan and Michał Kamiński formed a new political group, Poland Comes First (Polska jest Najważniejsza).[62] Kamiński said that the Law and Justice party had been taken over by far-right extremists. The breakaway party formed following dissatisfaction with the direction and leadership of Kaczyński.[63]

On 4 November 2011, MEPs Zbigniew Ziobro, Jacek Kurski, and Tadeusz Cymański were ejected from the party, after Ziobro urged the party to split further into two separate parties – centrist and nationalist – with the three representing the nationalist faction.[64] Ziobro's supporters, most of whom on the right-wing of the party, formed a new group in Parliament called Solidary Poland,[65] leading to their expulsion, too.[66] United Poland was formed as a formally separate party in March 2012, but has not threatened Law and Justice in opinion polls.[67]

Base of support

Like Civic Platform, but unlike the fringe parties to the right, Law and Justice originated from the anti-communist Solidarity trade union (which is a major cleavage in Polish politics), which was not a theocratic organisation.[68] Solidarity's leadership wanted to back Law and Justice in 2005, but was held back by the union's last experience of party politics, in backing Solidarity Electoral Action.[43]

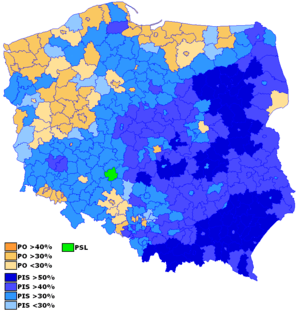

Today, the party enjoys great support among working class constituencies and union members. Groups that vote for the party include miners, farmers, shopkeepers, unskilled workers, the unemployed, and pensioners. With its left-wing approach toward economics, the party attracts voters who feel that economic liberalisation and European integration have left them behind.[69] The party's core support derives from older, religious people who value conservatism and patriotism. PiS voters are usually located in rural areas and small towns. The strongest region of support is the southeastern part of the country. Voters without a university degree tend to prefer the party more than college-educated voters do. Recently, younger voters have begun to support PiS more than in previous years.

Regionally, it has more support in regions of Poland that were historically part of western Galicia-Lodomeria and Congress Poland.[70] Since 2015, the borders of support are not as clear as before and party enjoys support in western parts of country, especially these deprived ones. Large cities in all regions are more likely to vote for more liberal party like PO or .N. Still PiS receives good support from poor and working class areas in large cities.

Based on this voter profile, Law and Justice forms the core of the conservative post-Solidarity bloc, along with the League of Polish Families and Solidarity Electoral Action, as opposed to liberal conservative post-Solidarity bloc of Civic Platform.[71] The most prominent feature of PiS voters was their emphasis on decommunisation.[72]

Ideology

Initially the party was broadly pro-market, although less so than the Civic Platform.[69] It has adopted the social market economy rhetoric similar to that of western European Christian democratic parties.[43] In the 2005 election, the party shifted to the protectionist left on economics.[69] As Prime Minister, Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz was more economically liberal than the Kaczyńskis, advocating a position closer to Civic Platform.[73] However, unlike Civic Platform, whose emphasis is the economy, Law and Justice's focus during their first term in power was fighting corruption.[69]

On foreign policy, PiS is Atlanticist and less supportive of European integration than Civic Platform.[69] The party is soft eurosceptic[74][75] and opposes a federal Europe. In its campaigns, it emphasises that the European Union should "benefit Poland and not the other way around".[76] It is a member of the anti-federalist European Conservatives and Reformists Party, having previously been a part of the Alliance for Europe of the Nations and, before that, the European People's Party.[43][77]

Platform

.jpg)

Economy

The party supports a state-guaranteed minimum social safety net and state intervention in the economy within market economy bounds. During the 2015 election campaign it proposed tax decrease to two personal tax rates (18% and 32%) and tax rebates related to the number of children in a family, as well as a reduction of the VAT rate (while keeping a variation between individual types of VAT rates). 18% and 32% tax rates were eventually implemented. Also: a continuation of privatization with the exclusion of several dozen state companies deemed to be of strategic importance for the country. PiS opposes cutting social welfare spending, and also proposed the introduction of a system of state-guaranteed housing loans. PiS supports state provided universal health care.[78]

National political structures

.jpg)

PiS has presented a project for constitutional reform including, among others: allowing the president the right to pass laws by decree (when prompted to do so by the Cabinet), a reduction of the number of members of the Sejm and Senat, and removal of constitutional bodies overseeing the media and monetary policy. PiS advocates increased criminal penalties. It postulates aggressive anti-corruption measures (including creation of an Anti-Corruption Bureau (CBA), open disclosure of the assets of politicians and important public servants), as well as broad and various measures to smooth the working of public institutions.

PiS is a strong supporter of lustration (lustracja), a verification system created ostensibly to combat the influence of the Communist era security apparatus in Polish society. While current lustration laws require the verification of those who serve in public offices, PiS wants to expand the process to include university professors, lawyers, journalists, managers of large companies, and others performing "public functions". Those found to have collaborated with the security service, according to the party, should be forbidden to practice in their professions.

Diplomacy and defense

The party is in favour of strengthening the Polish Army through diminishing bureaucracy and raising military expenditures, especially for modernization of army equipment. PiS planned to introduce a fully professional army and end conscription by 2012 (in August 2008, compulsory military service was abolished in Poland). It is also in favor of participation of Poland in foreign military missions led by the United Nations, NATO and United States, in countries like Afghanistan and Iraq.

.jpg)

The party supports integration with the European Union on terms beneficial for Poland. It supports economic integration and tightening the cooperation in areas of energetic security and military, but is skeptical about closer political integration. It is against formation of European superstate or federation. PiS is in favor of strong political and military alliance of Poland with the United States.

In the European Parliament it is a member of the European Conservatives and Reformists, a group founded in 2009 to challenge the prevailing pro-federalist ethos of the European Parliament and address the perceived democratic deficit existing at a European level.

Social policies

The party's views on social issues are much more traditionalist than those of social conservative parties in other European countries.

Family policies

The party strongly promotes itself as a pro-family party and encourages married couples to have more children. Prior to 2005 elections, it promised to build 3 million inexpensive housing units as a way to help young couples start a family. Once in government, it passed legislation lengthening parental leaves.

In 2017, the PiS government commenced the so-called "500+" programme under which all parents residing in Poland receive an unconditional monthly payment of 500 PLN for each second and subsequent child (the 500 PLN support for the first child being linked to income). It also revived the idea of a housing programme based on state-supported construction of inexpensive housing units.

Also in 2017, the party's MPs passed a law that bans most retail trade on Sundays so that workers can spend more time with their families.

Abortion stance

Even as Poland's abortion laws are among the most restrictive in the European Union, PiS additionally opposes abortion resulting from foetal defects[79] which is currently allowed until specific foetal age.

The party is also against euthanasia and comprehensive sex education. It has also proposed a ban of in-vitro fertilisation.

Disability rights

In April 2018, the PiS government announced a PLN 23 billion (EUR 5.5 billion) programme (named "Accessibility+") aimed at reducing barriers for disabled people, to be implemented 2018–2025.[80][81]

Also in April 2018, parents of disabled adults who required long-term care protested in Sejm over what they considered inadequate state support, in particular, the reduction of support once the child turns 18.[82][83] As a result, the monthly disability benefit for adults was raised by approx. 15 percent to PLN 1,000 (approx. EUR 240) and certain non-cash benefits were instituted, although protesters' demands of an additional monthly cash benefit were rejected.

Gay rights

The party opposes LGBT rights, in particular same-sex marriages and any other form of legal recognition of same-sex couples.

On 21 September 2005, Jarosław Kaczyński said that "homosexuals should not be isolated, however they should not be school teachers for example. Active homosexuals surely not, in any case", but that homosexuals "should not be discriminated otherwise".[84] He has also stated, "The affirmation of homosexuality will lead to the downfall of civilization. We can't agree to it".[85] Lech Kaczynski, while mayor of Warsaw, refused authorization for a gay pride march; declaring that it would be obscene and offensive to other people's religious beliefs. A Warsaw court later ruled that Kaczynski's actions were illegal.[86] Kaczyński was quoted as saying, "I am not willing to meet perverts."[87]

In 2016 Beata Szydło's government disbanded the Council for the Prevention of Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Intolerance, an advisory body set up in 2011 by then-Prime Minister Donald Tusk. The council monitored, advised and coordinated government action against racism, discrimination and hate crime.[88][89]

Nationalism

Despite being labeled by many former Western Bloc States as a "nationalist" party, PiS' leadership constantly criticizes being offered such label. During the 2008 Polish Independence Day celebrations, Lech Kaczyński said in his speech during the visit to the city of Elbląg that "the state is a great value, and attachment to the state, to one's fatherland, we call patriotism - beware of the word nationalism, as nationalism is evil!"[90] On the same day during the celebrations in Warsaw, L. Kaczyński again stated: "patriotism doesn't equal nationalism."[91] In 2011, Jarosław Kaczyński criticized pre-war Polish nationalism for "its intellectual, political and moral failure" by emphasising that the movement "did not know how to deal with and solve the problems of Polish minorities."[92] Both Kaczyńskis twins look up for inspirations to the pre-war Sanacja movement with its leader Józef Piłsudski, in contrast to the nationalist Endecja that was led by Piłsudski's political archrival, Roman Dmowski. In February 2016, politician Paweł Kowal called Jarosław Kaczyński a "centre-right politician" who "just like Piłsudski before the war, he stopped the raise of nationalism in Poland at the time when such ideology clearly gains politically in Western Europe."[93] Polish far-right organizations and parties such as National Revival of Poland, National Movement and Autonomous Nationalists regularly criticize PiS' relative ideological moderation and its politicians for "monopolizing" official political scene by playing on the popular patriotic and religious feelings.[94][95][96] However, the party does include several overtly nationalist politicians in senior positions, such as Digital Affairs Minister Adam Andruszkiewicz, the former leader of the All-Polish Youth;[97] and deputy PiS leader and former Defence Minister Antoni Macierewicz, the founder of the National-Catholic Movement.[98]

Refugee and economic migrant policies

PiS opposed the quota system for mass relocation of immigrants proposed by the European Commission to address the 2015 European migrant crisis. This contrasted with the stance of their main political opponents, the Civic Platform, which have signed up to the Commission's proposal.[99] Consequently, in the campaign leading to the 2015 Polish parliamentary election, PiS adopted the discourse typical of the populist-right, linking national security with immigration.[100] Following the election, PiS sometimes utilised Islamophobic rhetoric to rally its supporters.[101]

Examples of anti-migration and anti-Islam comments by PiS politicians when discussing the European migrant crisis:[102] in 2015, Jarosław Kaczyński stated that Poland "can't" accept any refugees because "they could spread infectious diseases."[103] In 2017, the first Deputy Minister of Justice Patryk Jaki stated that "stopping Islamization is his Westerplatte".[104] In 2017, Interior minister of Poland Mariusz Błaszczak stated that he would like to be like "Charles the Hammer who stopped the Muslim invasion of Europe in the 8th century". In 2017, Deputy Speaker of the Sejm Joachim Brudziński stated during the pro-party rally in Siedlce; "if not for us (PiS), they (Muslims) would have built mosques in here (Poland)."[105]

Leadership

Party chairmen

- Lech Kaczyński (2001–2003)

- Jarosław Kaczyński (2003–present)

Election results

Sejm

| Election year | Leader | # of votes |

% of vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Lech Kaczyński | 1,236,787 | 9.5 (#4) | 44 / 460 |

SLD–UP–PSL | |

| SLD–UP Minority | ||||||

| 2005 | Jarosław Kaczyński | 3,185,714 | 27.0 (#1) | 155 / 460 |

PiS–SRP–LPR | |

| 2007 | Jarosław Kaczyński | 5,183,477 | 32.1 (#2) | 166 / 460 |

PO–PSL | |

| 2011 | Jarosław Kaczyński | 4,295,016 | 29.9 (#2) | 157 / 460 |

PO–PSL | |

| 2015 | Jarosław Kaczyński | 5,711,687 | 37.6 (#1) | 217 / 460 |

PiS | |

| As a part of the United Right coalition, which won 235 seats in total.[106] | ||||||

| 2019 | Jarosław Kaczyński | 8,051,935 | 43.6 (#1) | 199 / 460 |

PiS | |

| As a part of the United Right coalition, which won 235 seats in total. | ||||||

Senate

| Election year | # of overall seats won |

+/– | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 0 / 100 |

|||||

| As part of the Senate 2001 coalition, which won 15 seats. | ||||||

| 2005 | 49 / 100 |

|||||

| 2007 | 39 / 100 |

|||||

| 2011 | 31 / 100 |

|||||

| 2015 | 61 / 100 |

|||||

| 2019 | 48 / 100 |

|||||

European Parliament

| Election year | # of votes |

% of vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 771,858 | 12.7 (#3) | 7 / 54 |

|

| 2009 | 2,017,607 | 27.4 (#2) | 15 / 50 |

|

| 2014 | 2,246,870 | 31.8 (#2) | 19 / 51 * |

|

| 2019 | 6,192,780 | 45.38 (#1) | 27 / 51 * |

*Currently 16: Zdzisław Krasnodębski is elected from the PiS register, but not a member of the party, Mirosław Piotrowski left PiS (08.10.2014), Marek Jurek is a member of Right Wing of the Republic.

Presidential

| Election year | Candidate | 1st round | 2nd round | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of overall votes | % of overall vote | # of overall votes | % of overall vote | ||

| 2005 | Lech Kaczyński | 4,947,927 | 33.1 (#2) | 8,257,468 | 54.0 (#1) |

| 2010 | Jarosław Kaczyński | 6,128,255 | 36.5 (#2) | 7,919,134 | 47.0 (#2) |

| 2015 | Andrzej Duda | 5,179,092 | 34.8 (#1) | 8,719,281 | 51.5 (#1) |

| 2020 | Supporting Andrzej Duda | ||||

Regional assemblies

| Election year | % of vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 12.1 (#4) | 79 / 561 | ||||

| In coalition with Civic Platform. | ||||||

| 2006 | 25.1 (#2) | 170 / 561 |

||||

| 2010 | 23.1 (#2) | 141 / 561 |

||||

| 2014 | 26.9 (#1) | 171 / 555 |

||||

| 2018 | 34.3 (#1) | 254 / 552 |

||||

Presidents of the Republic of Poland from PiS

| Name | Image | From | To |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lech Kaczyński |  |

23 December 2005 | 10 April 2010 (died in plane crash) |

| Andrzej Duda | 6 August 2015 | incumbent | |

Prime Ministers of the Republic of Poland from PiS

| Name | Image | From | To |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz | _cropped.jpg) |

31 October 2005 | 14 July 2006 |

| Jarosław Kaczyński | _(cropped_2).jpg) |

14 July 2006 | 16 November 2007 |

| Beata Szydło | _(cropped_3).jpg) |

16 November 2015 | 11 December 2017 |

| Mateusz Morawiecki | .jpg) |

11 December 2017 | incumbent |

Voivodeship Marshals

| Name | Image | Voivodeship | Date vocation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grzegorz Schreiber |  |

Łódź Voivodeship | 22 November 2018 |

| Jarosław Stawiarski |  |

Lublin Voivodeship | 21 November 2018 |

| Władysław Ortyl |  |

Podkarpackie Voivodeship | 27 May 2013 |

| Jakub Chełstowski |  |

Silesian Voivodeship | 21 November 2018 |

| Andrzej Bętkowski |  |

Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship | 22 November 2018 |

| Witold Kozłowski | Lesser Poland Voivodeship | 19 November 2018 | |

| Artur Kosicki | Podlaskie Voivodeship | 11 December 2018 |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prawo i Sprawiedliwość. |

- Committee for the Defence of Democracy

- Citizens of Poland (movement)

- Fidesz (Hungary)

- List of Law and Justice politicians

- Polish constitutional crisis, 2015

- Polish nationalism

- 2010 Polish Air Force Tu-154 crash

Footnotes

- "Wniosek o udostępnienie informacji publicznej". Imgur. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Hloušek, Vít; Kopeček, Lubomír (2010), Origin, Ideology and Transformation of Political Parties: East-Central and Western Europe Compared, Ashgate, p. 196

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2019). "Poland". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "PiS - Mamy program dla Polski u dla Unii Europejskiej". pis.pl.

- "Pawłowicz:Unia Europejska to dla mnie szmata". Wirtualna Polska.

- https://www.economist.com/europe/2018/08/09/polands-government-wants-to-take-control-of-banking

- https://www.politico.eu/article/poland-needs-more-liberalism-not-less/

- "Program działań Prawa i Sprawiedliwości. Tworzenie szans dla wszystkich". Instytut Sobieskiego. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- "Dossier: What PiS would change in the economy". Polityka Insight. PI Research. October 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- Elliott, Dominic (26 October 2015). "Poland's tilt to nationalism is bad for investment".

- Why is Poland's government worrying the EU? The Economist. Published 12 January 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- Dominik Hierlemann, ed. (2005). Lobbying der katholischen Kirche: Das Einflussnetz des Klerus in Polen. Springer-Verlag. p. 131. ISBN 978-3531146607.

- "Unentschlossene als Zünglein an der Waage". News ORF. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- "EU takes Poland to court over judicial crackdown". Axios. 24 September 2018.

- "European Court of Justice orders Poland to stop purging its supreme court judges". The Independent. 19 October 2018.

- "After Loss in Austria, a Look at Europe's Right-wing Parties". Haaretz. 24 May 2016.

- Henceroth, Nathan (2019). "Open Society Foundations". In Ainsworth, Scott H.; Harward, Brian M. (eds.). Political Groups, Parties, and Organizations that Shaped America. ABC-CLIO. p. 739.

- {{cite web|url=https://www.rp.pl/Rzecz-o-polityce/303299876-Jaroslaw-Kaczynski-z-Romana-Dmowskiego.html?preview=1&remainingPreview=4&grantedBy=preview&#ap-1}

- "Antoni Macierewicz: Wieś jest w centrum programy PiS" [Antoni Macierewicz: Polish countryside is at the center of the PiS program]. Polskie Radio 24 (in Polish). 6 April 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- Joanna Solska (6 April 2019). "Konwencja rolnicza w Kadzidle. PiS znów stawia na wieś" [Agricultural Convention in Kadzidło. PiS again puts on the countryside]. Polityka (in Polish). Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- SJ, MNIE (26 May 2019). "PiS wygrywa na wsi. KE w miastach" [PiS has won in the countryside. KE in cities]. TVPinfo (in Polish).

- Stijn van Kessel (2015). Populist Parties in Europe: Agents of Discontent?. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-137-41411-3.

- Łukasz Warzecha (20 April 2018). "PiS, Czyli Populizm i Socjalizm" [PiS means Populism and Socialism] (in Polish). Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Family, faith, flag: the religious right and the battle for Poland's soul". The Guardian. 5 October 2019.

- "The Rise of Poland's Far Right". Foreign Affairs. 18 December 2017.

- Traub, James (2 November 2016). "The Party That Wants to Make Poland Great Again". The New York Times Magazine.

- Adekoya, Remi (25 October 2016). "Xenophobic, authoritarian – and generous on welfare: how Poland's right rules". The Guardian.

- "Protests grow against Poland's nationalist government". The Economist. 20 December 2016.

- Michael Minkenberg (2013). "Between Tradition and Transition: the Central European Radical Right and the New European Order". In Christina Schori Liang (ed.). Europe for the Europeans: The Foreign and Security Policy of the Populist Radical Right. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-4094-9825-4.

- Lenka Bustikova (2018). "The Radical Right in Eastern Europe". In Jens Rydgren (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right. Oxford University Press. p. 574. ISBN 978-0-19-027455-9.

- Aleks Szczerbiak (2012). Poland Within the European Union: New Awkward Partner Or New Heart of Europe?. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-415-38073-7.

- Fijołek, Marcin (2012). "Republikańska symbolika w logotypie partii politycznej Prawo i Sprawiedliwość". Ekonomia i Nauki Humanistyczne (19): 9–17. doi:10.7862/rz.2012.einh.23.

- Electoral coalition, 235 seats in total

- Electoral coalition, 48 seats in total

- Electoral coalition, 27 seats in total

- "Partie polityczne i ruchy społeczne w Polsce" (in Polish). ewybory.eu. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- Łukasz Warzecha (20 April 2018). "PiS, Czyli Populizm i Socjalizm" [PiS means Populism and Socialism] (in Polish). Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- Goluch, oprac Bartosz (21 July 2019). "Premier o PiS. "Myśl socjalistyczna również jest dla nas ważna"". wiadomosci.wp.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Największe amerykańskie media piszą o Polsce – "Ten kraj wrócił do ustroju sprzed 89. roku"". naTemat.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Why Trump is likely to get a warm welcome in Poland". NBC News. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Subscribe to read". Financial Times. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (5 June 2019). Parties and Elections in Europe: Parliamentary Elections and Governments since 1945, European Parliament Elections, Political Orientation and History of Parties. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 9783732292509.

- Bale, Tim; Szczerbiak, Aleks (December 2006). "Why is there no Christian Democracy in Poland (and why does this matter)?". SEI Working Paper (91). Sussex European Institute. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Poland Ousts Government as Law & Justice Gains Historic Majority". Bloomberg. 25 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "Poland elections: Conservatives secure decisive win". 25 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- Tworzecki, Hubert; Markowski, Radosław (26 July 2017). "Why is Poland's Law and Justice Party trying to rein in the judiciary?". The Washington Post.

- "Is Poland a failing democracy?". politico.eu. 13 January 2016.

- "Stawką tych wyborów jest sama demokracja". wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- Klich, Bogdan. "Jak PiS demontuje polską demokrację". klich.pl.

- Węglarczyk, Bartosz (20 July 2017). "Już nie jesteśmy demokracją zachodnioeuropejską" (in Polish). onet.pl.

- Malinowski, Przemysław. "Nocna ofensywa PiS przeciwko demokracji" (in Polish). rp.pl.

- Kokot, Michał. "Polska na drodze ku demokracji nieliberalnej" (in Polish). wyborcza.pl.

- "Przyjdzie dzień, że w Warszawie będzie Budapeszt". tvn24.pl.

- "EU and Poland edge closer to showdown over judicial reform". Financial Times.

- Koper, Pawel; Sobczak, Anna. "Polish president backs down in judicial reform spat". Reuters.

- "The Observer view on Poland's assault on law and the judiciary". The Guardian. 22 July 2017.

- "How Poland's government is weakening democracy". The Economist.

- Marcinkiewicz, Kamil; Stegmaier, Mary (21 July 2017). "Poland appears to be dismantling its own hard-won democracy". The Washington Post.

- "Poland's ruling Law and Justice party is doing lasting damage". The Economist. 21 April 2018. ISSN 0013-0613.

- "Rząd PO-PSL wiedział o wyłudzeniach VAT. Kosztowało to państwo 260 mld zł". www.tvp.info (in Polish). Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Czy prezydent stolicy wzięła łapówkę? Reprywatyzacja krok po kroku". serwisy.gazetaprawna.pl. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Law and Justice breakaway politicians form new 'association', thenews.pl

- Conservatives' EU alliance in turmoil as Michał Kamiński leaves 'far right' party, The Guardian, 22 November 2010

- "Opposition party Law and Justice expels critics". Polskie Radio. 4 November 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- "Conservative MPs form 'Poland United' breakaway group after dismissals". TheNews.pl. 8 November 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- "MPs axed by Law and Justice opposition". TheNews.pl. 15 November 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- "New Polish conservative party launched". TheNews.pl. 26 March 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- Myant et al. (2008), p. 3

- Tiersky, Ronald; Jones, Erik (2007). Europe Today: a Twenty-first Century Introduction. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-7425-5501-3.

- Frank Jacobs, "Zombie Borders", The New York Times Opinionator blog, 12 December 2011

- Jungerstam-Mulders (2006), p. 104

- Jungerstam-Mulders (2006), p. 103

- Myant et al. (2008), pp. 67–68

- Myant et al. (2008), p. 88

- Szczerbiak, Aleks; Taggart, Paul A. (2008). Opposing Europe?. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-19-925830-7.

- Maier et al. (2006), p. 374

- Jungerstam-Mulders (2006), p. 100

- "PiS wygrywa: koniec NFZ, system budżetowy i sieć szpitali? - Polityka zdrowotna". www.rynekzdrowia.pl.

- "Jarosław Kaczyński o aborcji. Dzieci z zespołem Downa muszą żyć". Onet Wiadomości (in Polish). 14 October 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "Inauguracja Programu Dostępność Plus 2018-2025" (in Polish). Ministerstwo Inwestycji i Rozwoju. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "PiS przeznaczy 23 mld zł na program "Dostępność Plus"". Business Insider (in Polish). 17 July 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "Protest of disabled persons in the Sejm - communique from the Sejm Information Centre for the foreign media" (in Polish). Sejm. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "Parents of disabled children occupy Poland's parliament". Deutsche Welle. 26 April 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- Wiadomosci, PL.

- "Polish election", Gay mundo, The gully.

- "Poland: LGBT rights under attack". Amnesty International. Retrieved on 19 July 2009.

- "Poland: Official Homophobia Threatens Basic Freedoms". Human Rights Watch. 4 June 2006.

- "Polish PM abolishes anti-discrimination council". Radio Poland. 4 May 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Kelly, Lidia; Justyna, Pawlak (3 January 2018). "Poland's far-right: opportunity and threat for ruling PiS". Reuters. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- S.A., Wirtualna Polska Media (30 September 2008). "Prezydent L. Kaczyński: nacjonalizm jest złem".

- IAR. "Lech Kaczyński: Patriotyzm nie oznacza nacjonalizmu".

- "Jarosław Kaczyński z Romana Dmowskiego - Rzecz o polityce - rp.pl".

- "Kowal: Kaczyński powstrzymuje w Polsce nacjonalizm". Kresy - Portal Społeczności Kresowej.

- "Search Result | AUTONOM.PL | autonomiczni nacjonaliści nowoczesny nacjonalizm AN". autonom.pl.

- ""Prawo I Sprawiedliwość" | Nacjonalista.pl - Dziennik Narodowo-Radykalny". www.nacjonalista.pl.

- "Wyniki wyszukiwania dla „"Prawo i Sprawiedliwość"" – Xportal.pl".

- "Far-right Polish official steps back from radical comments". Seattle Times. 4 January 2019.

- "Polish minister accused of having links with pro-Kremlin far-right groups". The Guardian. 12 July 2017.

- Bachman, Bart (15 June 2016). "Diminishing Solidarity: Polish Attitudes toward the European Migration and Refugee Crisis". migrationpolicy.org. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- The Everyday Politics of Migration Crisis in Poland: Between Nationalism, Fear and Emphathy, Palgrave Macmillan, Krzysztof Jaskulowski, 2019, pages 38-45

- Jaskulowski, Krzysztof; Pawlak, Marek (11 April 2019). "Migration and Lived Experiences of Racism: The Case of High-Skilled Migrants in Wrocław, Poland". International Migration Review: 019791831983994. doi:10.1177/0197918319839947 – via DOI.org (Crossref).

- Wyborcza, Adam Leszczyński of Gazeta (2 July 2015). "'Poles don't want immigrants. They don't understand them, don't like them'". The Guardian.

- "Polish opposition warns refugees could spread infectious diseases". Reuters. 15 October 2015.

- "Kto chce zakazać Koranu w Polsce - Polityka - rp.pl".

- "W Siedlcach wiec poparcia dla rządu PiS". 9 September 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- Prawapolityka.pl Energetyka, samorządy, demografia – WYWIAD z dr Janem Klawiterem

References

- Jungerstam-Mulders, Susanne (2006). Post-Communist EU Member States: Parties and Party Systems. London: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-4712-6.

- Maier, Michaela; Tenscher, Jens (2004). Campaigning in Europe – Campaigning for Europe. Münster: LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-9322-4.

- Myant, Martin R.; Cox, Terry (2008). Reinventing Poland: Economic and Political Transformation and Evolving National Identity. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-45175-8.