Civic Platform

Civic Platform (Polish: Platforma Obywatelska, PO)[nb 1] is a liberal-conservative[4][5][6][7][8][9] political party in Poland. Civic Platform came to power following the 2007 general election as the major coalition partner in Poland's government, with party leader Donald Tusk as Prime Minister of Poland. Tusk was re-elected as Prime Minister in the 2011 general election but stepped down three years later to assume the post of President of the European Council. Prime Minister Ewa Kopacz led the party in the 2015 general election but was defeated by the Law and Justice party. On 16 November 2015 Civic Platform government stepped down after exactly 8 years in power. In 2010 Civic Platform candidate Bronisław Komorowski was elected as President of Poland, but failed in running for re-election in 2015. PO is the second largest party in the Sejm, with 138 seats, and the Senate, with 40 seats. Civic Platform is a member of the European People's Party (EPP). The party was formed in 2001 as a split from Solidarity Electoral Action (AWS), under the leadership of Andrzej Olechowski and Maciej Płażyński, with Donald Tusk of the Freedom Union (UW). In the 2001 general election, PO emerged as the largest opposition party, behind the ruling centre-left party Democratic Left Alliance (SLD). PO remained the second-largest party at the 2005 general election, but this time behind the national-conservative party Law and Justice (PiS). In 2007, Civic Platform overtook PiS, now established as the dominant parties, and formed a coalition government with the Polish People's Party. Following the Smolensk disaster of April 2010, Bronisław Komorowski became the first President from PO in the 2010 presidential election.

Civic Platform Platforma Obywatelska | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | PO |

| Chairman | Borys Budka |

| General Secretary | Marcin Kierwiński |

| Parliamentary Leader | Borys Budka (KO club) |

| Spokesperson | Jan Grabiec |

| Founder | Donald Tusk Andrzej Olechowski Maciej Płażyński |

| Founded | 24 January 2001 |

| Split from | Solidarity Electoral Action Freedom Union Conservative People's Party |

| Headquarters | ul. Władysława Andersa 21, 00-159 Warszawa |

| Youth wing | Association "Young Democrats" |

| Membership (2018) | 33,500[1] |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Centre to centre‑right |

| National affiliation | Civic Coalition |

| European affiliation | European People's Party |

| International affiliation | Centrist Democrat International |

| European Parliament group | European People's Party |

| Colours | Orange Blue |

| Sejm | 111 / 460 [2] |

| Senate | 40 / 100 [3] |

| European Parliament | 14 / 52 |

| Regional assemblies | 153 / 552 |

| Website | |

| www | |

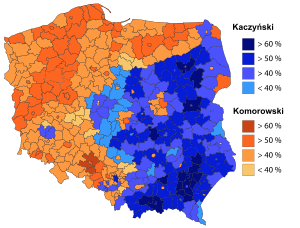

Since its creation, the party has shown stronger electoral performances in Warsaw, the west, and the north of Poland.[10]

History

The Civic Platform was founded in 2001 as economically liberal, Christian-democratic split from existing parties. Founders Andrzej Olechowski, Maciej Płażyński, and Donald Tusk were sometimes jokingly called "the Three Tenors" by Polish media and commentators. Olechowski and Płażyński left the party during the 2001–2005 parliamentary term, leaving Tusk as the sole remaining founder, and current party leader.

In the 2001 general election the party secured 12.6% of the vote and 65 deputies in the Sejm, making it the largest opposition party to the government led by the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD).

In the 2002 local elections PO stood together with Law and Justice in 15 voivodeships (in 14 as POPiS, in Podkarpacie with another centre-right political parties). They stood separately only in Mazovia.

In 2005, PO led all opinion polls with 26% to 30% of public support. However, in the 2005 general election, in which it was led by Jan Rokita, PO polled only 24.1% and unexpectedly came second to the 27% garnered by Law and Justice (PiS). A centre-right coalition of PO and PiS (nicknamed:PO-PiS) was deemed most likely to form a government after the election. Yet the putative coalition parties had a falling out in the wake of the fiercely contested Polish presidential election of 2005.

Lech Kaczyński (PiS) won the second round of the presidential election on 23 October 2005 with 54% of the vote, ahead of Tusk, the PO candidate. Due to the demands of PiS for control of all the armed ministries (the Defence Ministry, the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and the office of the Prime Minister, PO and PiS were unable to form a coalition. Instead, PiS formed a coalition government with the support of the League of Polish Families (LPR) and Self-Defense of the Republic of Poland (SRP). PO became the opposition to this PiS-led coalition government.

The PiS-led coalition fell apart in 2007 amid corruption scandal with Andrzej Lepper and Tomasz Lipiec[11] and internal leadership disputes. These events led to the new elections in 2007. In the 21 October 2007 parliamentary election, PO won 41.51% of the popular vote and 209 out of 460 seats (now 201) in the Sejm and 60 out of 100 seats (now 56) in the Senate of Poland. Civic Platform, now the largest party in both houses of parliament, subsequently formed a coalition with the Polish People's Party (PSL).

At the 2010 Polish presidential election, following the Smolensk air disaster which killed the incumbent Polish president Lech Kaczyński, Tusk decided not to present his candidature, considered an easy possible victory over PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński. During the PO primary elections, Bronisław Komorowski defeated the Oxford-educated, PiS defector Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski. At the polls, Komorowski defeated Jarosław Kaczyński, ensuring PO dominance over the current Polish political landscape.[12]

In November 2010, local elections granted Civic Platform about 30.1 percent of the votes and PiS at 23.2 percent, an increase for the former and a drop for the latter compared to the 2006 elections.[12]

PO succeeded in winning four consecutive elections (a record in post-communist Poland), and Tusk remains as kingmaker. PO's dominance is also a reflection of left-wing weakness and divisions on both sides of the political scene, with PiS suffering a splinter in Autumn 2010.[12]

The 9 October 2011 parliamentary election was won by Civic Platform with 39.18% of the popular vote, 207 of 460 seats in the Sejm, 63 out of 100 seats in the Senate.[13]

In the 2014 European elections, Civic Platform came first place nationally, achieving 32.13% of the vote and returning 19 MEPs.[14]

In the 2014 local elections, PO achieved 179 seats, the highest single number.[15]

In the 2015 presidential election, PO endorsed Bronisław Komorowski, a former member of PO from 2001 till 2010. He lost the election receiving 48.5% of the popular vote, while Andrzej Duda won with 51.5%.[16]

In the 2015 parliamentary election, PO came second place after PiS, achieving 39.18% of the popular vote, 138 out of 460 seats in the Sejm, 34 out of 100 seats in the Senate.[17]

In the 2018 local elections, PO achieved 26.97% of the votes, coming second after PiS.[18]

In the 2019 European elections, PO participated in the European Coalition electoral alliance which achieved 38.47%, coming second after PiS.[19]

Ideology

As a centrist[20][21][22][23][24] or centre-right[25][26][27][28] political party, Civic Platform has been described as liberal-conservative,[4][5][6][7][8][9] liberal,[28][29][30] conservative-liberal,[31][32][33][34][35] Christian democratic,[36] conservative,[37] neoliberal,[37] and pro-European.[38]

Civic Platform combines ordoliberal stances on the economy with social conservative stances on social and ethical issues, including opposition to abortion, same-sex marriage, soft drug decriminalisation, euthanasia, fetal stem cell research, removal of crosses and other religious symbols in schools and public places, and partially to wide availability of in vitro fertilisation. The party also wants to criminalise gambling and supports religious education in schools and civil unions. Other socially conservative stances of the party include voting to ban designer drugs and amending the penal code to introduce mandatory chemical castration of paedophiles.

Since 2007, when Civic Platform formed the government, the party has gradually moved from its liberal conservative stances, and many of its politicians hold more liberal positions on social issues. In 2013, the Civic Platform's government introduced public funding of in vitro fertilisation program. In 2017, the party supported a citizens' initiative for liberalisation of the abortion law. Civic Platform also supports civil unions for same-sex couples.

Despite declaring in the parliamentary election campaign the will to limit taxation in Poland, the Civic Platform has in fact increased it. The party refrained from implementing the flat tax, increasing instead the value-added tax from 22% to 23% in 2011.[39] It has also increased the excise imposed on diesel oil, alcoholic beverages, tobacco and oil.[40][41] The party has eliminated many tax exemptions.[42][43][44]

In response to the climate crisis, the Civic Platform has promised to end the use of coal for energy in Poland by 2040.[45]

Political support

Today, Civic Platform enjoys support amongst higher class constituencies. Professionals, academics, managers and businessmen vote for the party in large numbers. People with university degrees support the party more than less educated voters. PO voters tend to be those people who generally benefited from European integration and economic liberalisation since 1989 and are satisfied with their life standard. Many PO voters are social-liberals who value environmentalism, secularism and Europeanisation. Conservatives used to vote for the party before PO moved sharply to the left on economic (e.g., increase of taxes) and social issues (e.g., support for civil unions). Young people are another voting bloc that abandoned the party, after their economic and social situation did not improve significantly when PO was in government.

Areas that are more likely to vote for PO are in the west and north of the country, especially parts of the former Prussia before 1918. Many of these people previously used to vote for the Democratic Left Alliance when that party enjoyed support and influence. Large cities in the whole country prefer the party, rather than rural areas and smaller towns. This is caused by the diversity, secular and social liberalism urban voters tend to value. In urban areas, conservative principles are much less identified with by voters. Large cities in Poland have a better economic climate, which draws support to PO. Areas with higher concentration of minorities, such as Germans or Belarusians, support the party due to its smaller emphasis on patriotism and national conservatism.

Leadership

Chairmen

- Maciej Płażyński (18 October 2001 – 1 June 2003)

- Donald Tusk (1 June 2003– 8 November 2014)

- Ewa Kopacz (8 November 2014– 26 January 2016)

- Grzegorz Schetyna (26 January 2016– 29 January 2020)

- Borys Budka (since 29 January 2020)

Election results

Sejm

| Election year | Leader | # of votes |

% of vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Maciej Płażyński | 1,651,099 | 12.7 (#2) | 65 / 460 |

SLD–UP–PSL | |

| SLD–UP Minority | ||||||

| 2005 | Donald Tusk | 2,849,259 | 24.1 (#2) | 133 / 460 |

PiS Minority | |

| PiS–SRP–LPR | ||||||

| 2007 | Donald Tusk | 6,701,010 | 41.5 (#1) | 209 / 460 |

PO–PSL | |

| 2011 | Donald Tusk | 5,629,773 | 39.2 (#1) | 207 / 460 |

PO–PSL | |

| 2015 | Ewa Kopacz | 3,661,474 | 24.1 (#2) | 138 / 460 |

PiS | |

| 2019 | Grzegorz Schetyna | 5,060,355 | 27.4 (#2) | 119 / 460 |

PiS | |

| As part of Civic Coalition, which won 134 seats in total. | ||||||

Senate

| Election year | # of overall seats won |

+/– | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2 / 100 |

|||||

| As part of the Senate 2001 coalition, which won 15 seats. | ||||||

| 2005 | 34 / 100 |

|||||

| 2007 | 60 / 100 |

|||||

| 2011 | 63 / 100 |

|||||

| 2015 | 34 / 100 |

|||||

| 2019 | 43 / 100 |

|||||

Presidential

| Election year | Candidate | 1st round | 2nd round | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of overall votes | % of overall vote | # of overall votes | % of overall vote | ||

| 2005 | Donald Tusk | 5,429,666 | 36.3 (#1) | 7,022,319 | 46.0 (#2) |

| 2010 | Bronisław Komorowski | 6,981,319 | 41.5 (#1) | 8,933,887 | 53.0 (#1) |

| 2015 | Supported Bronisław Komorowski | 5,031,060 | 33.8 (#2) | 8,112,311 | 48.5 (#2) |

| 2020 | Rafał Trzaskowski | ||||

Regional assemblies

| Election year | % of vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 12.1 (#4) | 79 / 561 |

||||

| In coalition with Law and Justice (POPiS). | ||||||

| 2006 | 27.2 (#1) | 186 / 561 |

||||

| 2010 | 30.9 (#1) | 222 / 561 |

||||

| 2014 | 26.3 (#2) | 179 / 555 |

||||

| 2018 | 27.1 (#2) | 194 / 552 |

||||

| As a Civic Coalition. | ||||||

European Parliament

| Election year | # of votes |

% of vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 1,467,775 | 24.1 (#1) | 15 / 54 |

|||

| 2009 | 3,271,852 | 44.4 (#1) | 25 / 50 |

|||

| 2014 | 2,271,215 | 32.1 (#1) | 19 / 51 |

|||

| 2019 | 5,249 935 | 38,47 (#2) | 14 / 51 |

|||

| As a European Coalition | ||||||

Voivodeship Marshals

| Name | Image | Voivodeship | Date Vocation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elżbieta Polak | Lubusz Voivodeship | 29 November 2010 | |

| Marek Woźniak | Greater Poland Voivodeship | 10 October 2005 | |

| Piotr Całbecki | Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship | 24 January 2006 | |

| Olgierd Geblewicz |  |

West Pomeranian Voivodeship | 7 December 2010 |

| Mieczysław Struk | Pomeranian Voivodeship | 22 February 2010 | |

| Andrzej Buła |  |

Opole Voivodeship | 12 November 2013 |

Notable politicians

.jpg)

.jpg)

Donald Tusk former Prime Minister of Poland and President of the European Council, leader of European People's Party

Donald Tusk former Prime Minister of Poland and President of the European Council, leader of European People's Party

.jpg) Grzegorz Schetyna former Minister of Foreign Affairs

Grzegorz Schetyna former Minister of Foreign Affairs Bogdan Borusewicz former Marshal of the Senate

Bogdan Borusewicz former Marshal of the Senate- Hanna Gronkiewicz-Waltz former Mayor of Warsaw

See also

Notes

- The party is officially the Civic Platform of the Republic of Poland (Platforma Obywatelska Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej).

References

- "Wniosek o udostępnienie informacji publicznej". Imgur. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Electoral coalition, 134 seats in total

- Electoral coalition, 43 seats in total

- Aleks Szczerbiak (2006). "Power without Love? Patterns of Party Politics in Post-1989 Poland". In Susanne Jungerstam-Mulders (ed.). Post-Communist EU Member States: Parties and Party Systems. London: Ashgate. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-7546-4712-6.

- Vít Hloušek; Lubomír Kopeček (2010). Origin, Ideology and Transformation of Political Parties: East-Central and Western Europe Compared. Ashgate. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7546-7840-3. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- Hanley, Seán; Szczerbiak, Aleks; Haughton, Tim; Fowler, Brigid (July 2008). "Explaining Comparative Centre-Right Party Success in Post-Communist Central and Eastern Europe" (PDF). Party Politics. 14 (4): 407–434. doi:10.1177/1354068808090253.

- Seleny, Anna (July 2007). "Communism's Many Legacies in East-Central Europe". Journal of Democracy. 18 (3): 156–170. doi:10.1353/jod.2007.0056.

- Igor Guardiancich (2013). Pension Reforms in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe: From Post-Socialist Transition to the Global Financial Crisis. Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-415-68898-7.

- Jean-Michel De Waele; Anna Pacześniak (2012). "The Europeanisation of Poland's Political Parties and Party System". In Erol Külahci (ed.). Europeanisation and Party Politics: How the EU affects Domestic Actors, Patterns and Systems. ECPR Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-907301-84-1.

- See e.g. the results of the first round of the 2010 presidential election http://pl.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plik:Wybory_prezydenckie_2010_I_tura_BK.png&filetimestamp=20100622224054

- BBC News (2007-10-22): Massive win for Polish opposition

- Warsaw Business Journal Archived 20 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Elections 2011 - Election results". National Electoral Commission. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "Pkw | Pkw". Pe2014.pkw.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- "Oficjalne wyniki wyborów samorządowych. Zobacz, kto wygrał". TVN24.pl. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- Jęczmionka, Paulina. "Oficjalne wyniki wyborów 2015: Bronisław Komorowski wziął Poznań i Wielkopolskę [INFOGRAFIKA]". Gloswielkopolski.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- "Wybory parlamentarne 2015. PKW podała ostateczne wyniki". Onet Wiadomości (in Polish). 27 October 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- "Znamy wyniki wyborów! Relacja na żywo. Wybory samorządowe 2018". www.fakt.pl. 20 October 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- "Oficjalne wyniki wyborów do europarlamentu". TVN24.pl. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- "Polish Prime Minister Tusk Begins Building New Government After Winning Election". Fox News. Associated Press. 10 October 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Scislowska, Monika (8 December 2017). "Poland breaks norms and grants greater power to ruling party". Christian Science Monitor. Associated Press. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Sobczak, Pawel; Kelly, Lidia (12 January 2017). "Poland's centrist opposition ends blockade in parliament". Reuters. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- "Report: Polish lawmaker fears being target of arson attack". AP News. Associated Press. 27 May 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Chapman, Annabelle (12 February 2016). "The 10 faces of Poland's election". POLITICO. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Nathaniel Copsey (2013). "Poland:An Awkward Partner Redeemed". In Simon Bulmer; Christian Lequesne (eds.). The Member States of the European Union (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 191.

- Aleks Szczerbiak (2012). Poland Within the European Union: New awkward partner or new heart of Europe?. Routledge. p. 2.

- Viktor, Szary (9 September 2014). "Poland's PM Tusk, heading for Brussels, submits resignation". Reuters. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- David Ost (2011). "The decline of civil society after 'post-communism'". In Ulrike Liebert; Hans-Jörg Trenz (eds.). The New Politics of European Civil Society. Routledge. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-415-57845-5.

- Paul Kubicek (2017). European Politics. Taylor & Francis. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-317-20638-5.

- Tomasz Zarycki (2014). Ideologies of Eastness in Central and Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-317-81857-1.

- Florian Kellermann (4 February 2019). "Frühling" macht der linken Mitte Hoffnung. Deutschlandfunk.

- Slomp, Hans (2011). Europe, A Political Profile: An American Companion to European Politics. ABC-CLIO. p. 549. ISBN 9780313391828. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- Mart Laar (2010). The Power of Freedom - Central and Eastern Europe after 1945. Unitas Foundation. p. 229. ISBN 978-9949-21-479-2.

- Joanna A. Gorska (2012). Dealing with a Juggernaut: Analyzing Poland's Policy toward Russia, 1989-2009. Lexington Books. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-7391-4534-0.

- Bartek Pytlas (2016). Radical Right Parties in Central and Eastern Europe: Mainstream Party Competition and Electoral Fortune. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-317-49586-4.

- José Magone (2010). Contemporary European Politics: A Comparative Introduction. Routledge. p. 457. ISBN 978-0-203-84639-1. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Marjorie Castle (2015). "Poland". In M. Donald Hancock; Christopher J. Carman; Marjorie Castle; David P. Conradt; Raffaella Y. Nanetti; Robert Leonardi; William Safran; Stephen White (eds.). Politics in Europe. CQ Press. p. 636. ISBN 978-1-4833-2305-3.

- Ingo Peters (2011). 20 Years Since the Fall of the Berlin Wall: Transitions, State Break-Up and Democratic Politics in Central Europe and Germany. BWV Verlag. p. 280. ISBN 978-3-8305-1975-1. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- "Rzeczpospolita". rp.pl. 8 March 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- "ząd podwyższa akcyzę i zamraża płace". forsal.pl. 2 October 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- "Rząd zaciska pasa: zamraża pensje, podnosi akcyzę na papierosy i paliwa". wyborcza.biz. 23 October 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- "Dziś dowiemy się, dlaczego rząd zabierze nam ulgi". bankier.pl. 26 July 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Sebastian Bobrowski (25 March 2014). "Zmiany w odliczaniu VAT od samochodów. Sprawdź ile i kiedy możesz odliczyć". mamstartup.pl. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- "Głosowanie nad przyjęciem w całości projektu ustawy o zmianie niektórych ustaw związanych z realizacją ustawy budżetowej, w brzmieniu proponowanym przez Komisję Finansów Publicznych, wraz z przyjętymi poprawkami". sejm.gov.pl. 16 December 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- "Poland coal phase out pledged for 2040 by opposition government". Retrieved 12 October 2019.

Sources

- Adam Zakowski, A leading force, Polityka, March 2009

External links

- Official website