Lustration

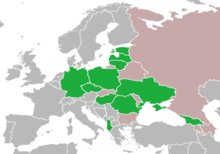

In politics, lustration refers to the purge of government officials in Central and Eastern Europe.[1] Various forms of lustration were employed in post-communist Europe and, more recently, in Ukraine.[2]

| Look up lustration in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Etymology

Lustration in general is the process of making something clear or pure, usually by means of a propitiatory offering. The term is taken from the Roman lustratio purification rituals.[3]

Policies and laws

After the fall of the various European Communist governments in 1989–1991, the term came to refer to government-sanctioned policies of "mass disqualification of those associated with the abuses under the prior regime".[4] Procedures excluded participation of former communists, and especially of informants of the communist secret police, in successor political positions, or even in civil service positions. This exclusion formed part of the wider decommunization campaigns. In some countries, however, lustration laws did not lead to exclusion and disqualification. Lustration law in Hungary (1994–2003) was based on the exposure of compromised state officials, while lustration law in Poland (1999–2005) depended on confession.[2]

Lustration law "is a special public employment law that regulates the process of examining whether a person holding certain higher public positions worked or collaborated with the repressive apparatus of the communist regime".[2] The "special" nature of lustration law refers to its transitional character. As of 1996, various lustration laws of varying scope were implemented in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Macedonia, Albania, Bulgaria, the Baltic States (Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia), Germany, Poland, and Romania.[5] As of 2019 lustration laws had not been passed in Belarus, nor in former Yugoslavia or the former Soviet Central Asian Republics (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan).

Results

Lustration can serve as a form of punishment by anti-communist politicians who were dissidents under a Communist-led government. Lustration laws are usually passed right before elections, and become tightened when right-wing governments are in power, and loosened while social democratic parties are in power.[6] It is claimed that lustration systems based on dismissal or confession might be able to increase trust in government,[7] while those based on confession might be able to promote social reconciliation.[7]

Examples

In Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic

Unlike many neighbouring states, the new government in the Czech and Slovak Federative Republic did not adjudicate under court trials, but instead took a non-judicial approach to ensure changes would be implemented.

According to a law passed on 4 October 1991, all employees of the StB, the Communist-era secret police, were blacklisted from designated public offices, including the upper levels of the civil service, the judiciary, procuracy, Security Information Service (BIS), army positions, management of state owned enterprises, the central bank, the railways, senior academic positions and the public electronic media. This law remained in place in the Czech Republic after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, and expired in 2000.

The lustration laws in Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic were not intended to serve as justice, but to ensure that events such as the Communist coup of February 1948 did not happen again.[8]

In Germany

Germany did not have a lustration process, but it has a federal agency, known as the Stasi Records Agency, dedicated to preserving and protecting the archives and investigating the past actions of the former East German secret police, the Stasi. The agency is subordinate to the Representative of the Federal Government for Culture (Bernd Neumann, CDU). As of 2012, it had 1,708 employees.[9]

In Poland

The first lustration bill was passed by the Polish Parliament in 1992, but it was declared unconstitutional by the Constitutional Tribunal of the Republic of Poland. Several other projects were then submitted and reviewed by a dedicated commission, resulting in a new lustration law passed in 1996.[10] From 1997 to 2007 lustration was dealt with by the office of the Public Interest Spokesperson (Polish: Rzecznik Interesu Publicznego), who analyzed lustration declarations and could initiate further proceedings. According to a new law which came into effect on 15 March 2007, lustration in Poland is now administered by the Institute of National Remembrance (Polish: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej; IPN).[11][12]

In Ukraine

In Ukraine, the term lustration refers mainly to the removal from public office of civil servants who worked under Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych. They may be excluded for five to ten years.[13]

Similar concepts

Lustration has been compared to denazification in post-World War II Europe, and the de-Ba'athification in post-Saddam Hussein Iraq.[4]

See also

Further reading

- Williams, "A Scorecard for Czech Lustration", Central Europe Review

- Jiřina Šiklová, "Lustration or the Czech Way of Screening", East European Constitutional Review, Vol.5, No.1, Winter 1996, Univ. of Chicago Law School and Central European University

- Rohozinska, "Struggling with the Past - Poland's controversial Lustration trials", Central European Review

- Human Rights Watch[14]

- Roman David, Lustration and Transitional Justice: Personnel Systems in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

- 1904 (Merriam) Webster's International Dictionary of the English Language says: "a sacrifice, or ceremony, by which cities, fields, armies, or people, defiled by crimes, pestilence, or other cause of uncleanness, were purified"

References

- "In Ukraine's Corridors Of Power, An Effort To Toss Out The Old". NPR. 2014-05-07. Retrieved 2014-05-07.

- Roman David (2003). ""Lustration Laws in Action: The Motives and Evaluation of Lustration Policy in the Czech Republic and Poland (1989-2001)" (PDF). Law & Social Inquiry. 28 (2): 387–439.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 131.

- Eric Brahm, "Lustration", Beyond Intractability.org, June 2004, 8 Sep 2009

- Nalepa, Monika (2010). Skeletons in the Closet: Transitional Justice in Post-Communist Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 99.

- Elster, Jon, ed. (2006). Retribution and Reparation in the Transition to Democracy. Cambridge University Press. p. 189.

- Roman David, Lustration and Transitional Justice: Personnel Systems in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011, pp. 183, 209

- Kieran Williams, "Lustration" Archived 2019-04-08 at the Wayback Machine, Central Europe Review

- "BStU - BStU in Zahlen". Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records. Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records. 30 June 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- Mark S. Ellis, Purging the past: The Current State of Lustration Laws in the Former Communist Bloc Archived 2013-11-01 at the Wayback Machine (pdf), Law and Contemporary Problems, Vol. 59, No. 4, Accountability for International Crimes and Serious Violations of Fundamental Human Rights (Autumn, 1996), pp. 181–96

- (in Polish) Najważniejsze wiadomości – Informacje i materiały pomocnicze dla organów realizujących postanowienia ustawy lustracyjnej IPN News. Last accessed on 24 April 2007

- (in Polish) Biuro Lustracyjne IPN w miejsce Rzecznika Interesu Publicznego, Gazeta Wyborcza, 15 March 2007, Last accessed on 24 April 2007

- "Lustration law faces sabotage, legal hurdles". Kyiv Post. 23 October 2014.

- "Hsw". Hrw.org. Retrieved 7 November 2017.