Economic liberalism

Economic liberalism is a political and economic philosophy based on strong support for a market economy and private property in the means of production. Although economic liberals can also be supportive of government regulation to a certain degree, they tend to oppose government intervention in the free market when it inhibits free trade and open competition. Economic liberalism has been described as representing the economic expression of liberalism.

As an economic system, economic liberalism is organized on individual lines, meaning that the greatest possible number of economic decisions are made by individuals or households rather than by collective institutions or organizations.[1] An economy that is managed according to these precepts may be described as liberal capitalism or liberal economy.

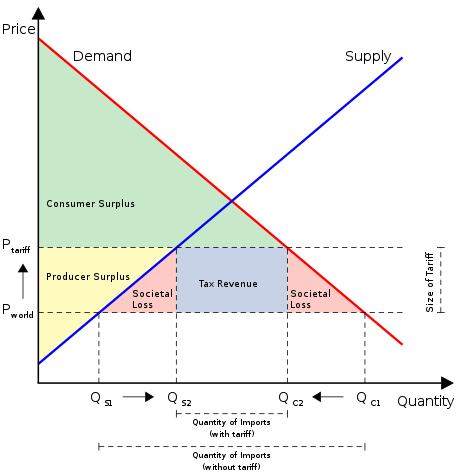

Economic liberalism is associated with free markets and private ownership of capital assets. Historically, economic liberalism arose in response to mercantilism and feudalism. Today, economic liberalism is also considered opposed to non-capitalist economic orders such as socialism and planned economies.[2] It also contrasts with protectionism because of its support for free trade and open markets.

Origins

Arguments in favor of economic liberalism were advanced during the Enlightenment, opposing mercantilism and feudalism. It was first analyzed by Adam Smith in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) which advocated minimal interference of government in a market economy, although it did not necessarily oppose the state's provision of basic public goods.[3] Smith claimed that if everyone is left to his own economic devices instead of being controlled by the state, the result would be a harmonious and more equal society of ever-increasing prosperity.[1] This underpinned the move towards a capitalist economic system in the late 18th century and the subsequent demise of the mercantilist system.

Private property and individual contracts form the basis of economic liberalism.[4] The early theory was based on the assumption that the economic actions of individuals are largely based on self-interest (invisible hand) and that allowing them to act without any restrictions will produce the best results for everyone (spontaneous order), provided that at least minimum standards of public information and justice exist. For example, no one should be allowed to coerce, steal, or commit fraud and there is freedom of speech and press.

Initially, the economic liberals had to contend with the supporters of feudal privileges for the wealthy, aristocratic traditions and the rights of kings to run national economies in their own personal interests. By the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, these were largely defeated.

Today, economic liberalism is associated with classical liberalism, neoliberalism, right-libertarianism and some schools of conservatism such as liberal conservatism.

Position on state interventionism

Economic liberalism opposes government intervention on the grounds that the state often serves dominant business interests, distorting the market to their favor and thus leading to inefficient outcomes.[5] Ordoliberalism and various schools of social liberalism based on classical liberalism include a broader role for the state, but they do not seek to replace private enterprise and the free market with public enterprise and economic planning.[6][7] For example, a social market economy is a largely free market economy based on a free price system and private property, but it is supportive of government activity to promote competitive markets and social welfare programs to address social inequalities that result from market outcomes.[6][7]

Historian Kathleen G. Donohue argues that classical liberalism in the United States during the 19th century had distinctive characteristics as opposed to Britain:

[A]t the center of classical liberal theory [in Europe] was the idea of laissez-faire. To the vast majority of American classical liberals, however, laissez-faire did not mean no government intervention at all. On the contrary, they were more than willing to see government provide tariffs, railroad subsidies, and internal improvements, all of which benefited producers. What they condemned was intervention in behalf of consumers.[8]

See also

References

- Adams 2001, p. 20.

- Brown, Wendy (2005). Edgework: Critical Essays on Knowledge And Politics. Princeton University Press. p. 39.

- Aaron, Eric (2003). What's Right?. Dural, Australia: Rosenberg Publishing. p. 75.

- Butler 2015, p. 10.

- Turner 2008, p. 60-61.

- Turner 2008, pp. 83–84.

- Balaam & Dillman 2015, p. 48.

- Donohue, Kathleen G. (2005). Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Idea of the Consumer. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780801883910.

Bibliography

- Adams, Ian (2001). Political Ideology Today. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-719-06020-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Balaam, David N; Dillman, Bradford (2015). Introduction to International Political Economy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-34730-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Butler, Eamonn (2015). Classical Liberalism – A Primer. Do Sustainability. ISBN 978-0-255-36708-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turner, Rachel S. (2008). Neo-Liberal Ideology: History, Concepts and Policies. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-748-68868-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)